THE LAST CHAPTER looked at how Mary Wollstonecraft and Hannah More answered for themselves the question of how to live one’s life. This one looks at the general answer given to girls and women: Be good! Middle-class girls of this period were raised to see motherhood as heroic, and wifehood as a profession. The gain was that they and their educations had begun to be taken seriously, although real reform in girls’ education did not come until the 1870s. The cost was that education was seen as worth seeking for only two primary purposes: the pursuit of a husband and the improvement of one’s children. This chapter will look at ideas of virtue through the lives of three very different women: a daughter, a mother, and a wife.

A DAUGHTER: PRINCESS CHARLOTTE (1796–1817)

Hannah More pitched her writing carefully to different audiences, and undoubtedly her two-volume work of 1805, Hints Towards Forming the Character of a Young Princess, had the most select readership of all. The princess in question was Charlotte Augusta, born in 1796, the only product of the disastrous marriage of the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) and Princess (later Queen) Caroline, and, after her father, heir apparent to the throne of England. Because Charlotte was in line to be ruler of Britain, More’s aim was to prepare the princess for her responsibilities to her people. Extra measures were called for: Latin, not customary for girls, was recommended, along with French and German, since these would all be helpful with history and foreign policy, while music was to be avoided since it would “lessen rather than augment the dignity of a sovereign.”1 More’s ambitions for teaching the princess were not just literary; she was aiming at the open position as Princess Charlotte’s tutor.2 (The job, however, went to the Bishop of Exeter.)

If she had been appointed, she would have had her hands full. In 1805, the nine-year-old Charlotte was rarely allowed to see her parents, who loathed each other and had little time for her. She was being raised in the very small world of the royal palaces by governesses and tutors who tried unsuccessfully to instill self-discipline in their charge. Discipline from others she had in abundance: her freedom to leave the palace grounds was strictly controlled. Charlotte felt like a prisoner, and books meant for her improvement would probably have seemed only like one more method of control. When, in 1812, Dr. Fisher, the bishop-tutor, tried to engage Charlotte with Hannah More’s book, she responded with asperity: “I am not quite good enough for that yet,” she wrote to her best friend.3 Others agreed; she was a handsome girl, but her manner was “extreme, awkward, neglected,” and visitors saw her “lolling and lounging about without any self control.”4 Yet a miniature of her at eleven shows a girl unafraid to look the viewer directly in the eye; if she lacked self-control, Princess Charlotte was gifted with self-possession.

After one heroic moment in which she insisted on her own choice of husband, Princess Charlotte might have had a career as an excellent wife, but her married life, cut short by her untimely death, was so brief that there is no way to know how it would have turned out. Her parents could hardly have set a worse example. Charlotte’s mother, Princess Caroline of Brunswick, was imported from Germany to marry her cousin George. She was young, lively, handsome, uneducated, coarse in her conversation, and prone to reckless acts. (Her adventures as an adulterous wife will be pursued in Chapter Four.) For his part, the Prince of Wales was interested in the marriage solely because of his debts. In 1795 these amounted to over £600,000, which Parliament might be induced to pay if he would only take a royal Protestant as a wife. He expected Caroline to live in the same household with his mistress, Lady Jersey; worse, he was already secretly married, to the Catholic commoner Maria Fitzherbert. In later years Caroline liked to say that “her only real sin had been to commit adultery with Mrs. Fitzherbert’s husband.”5 Although Caroline tried to make herself appealing to her new husband, he loathed her nearly on sight and was drunk on their wedding night–drunk, in fact, at the wedding itself.6 Charlotte, their only child, was born almost nine months to the day of their wedding. Although it had become fashionable for even wealthy women to nurse their own children, Caroline did not do so, and as Charlotte was growing up Caroline was allowed to see her daughter only about once a week. The princess’s closest contacts were with her grandparents, especially her grandmother, Queen Charlotte, who was stiff and cold, and her aunts, some of whom adored the little girl.

A self-possessed princess

Princess Charlotte was the difficult child of far more difficult parents, Princess Caroline and the future George IV. Yet a miniature of her at eleven shows a girl boldly gazing at the viewer. The hallmark of her brief life was courage in confined situations. Richard Cosway’s 1807 miniature, painted in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, shows her already a symbol of British patriotism, the dove signifying hope for peace. Her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte of Wales, engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, after Cosway. PRINT COLLECTION

In 1806, when Charlotte was ten, her mother underwent a “Delicate Investigation,” as it was called, into the possibility that Caroline was adulterous, which effectively prevented the possibility that she and her daughter might ever become close. Caroline was exonerated, but the evidence showed that she had behaved very strangely, pretending to be pregnant, and sending abusive anonymous letters and pornographic images through the post to her enemies; in the words of one biographer, she was “although not clinically insane … unquestionably unstable.”7 After this, her contact with her daughter was even further curtailed, and the enmity between her and the Prince of Wales cemented. Charlotte was well aware that she was a pawn of both her parents, but she remained loyal to her mother while her relations with her father deteriorated as she grew up and wished for more independence. She is said to have told a friend that although Caroline was bad, “she would not have become as bad as she was if my father had not been infinitely worse.”8

Her mother was unreliable for affection or anything else, and Charlotte, although much attended to, was starved for affection in the nursery as well. She may have had attentions that she did not want, as one of her governesses, a Mrs. Udney, is said to have shown and explained pornographic drawings to her.9 Training in virtue did not yet imply that girls should be sexually ignorant, and this was the age of the double-entendre. Writers of newspaper gossip columns used extended sexual metaphors that they expected their readers to understand. Shame derived, rather, from explicitness: Mrs. Udney’s worst sin, in the reports of the time, was her willingness to talk to the princess about sex. When Mary Wollstonecraft claimed that we should be able to talk about our genitals with as little embarrassment as we talk about our hands or faces, and declared that purity of mind, “so far from being incompatible with knowledge, is its fairest fruit,” she was herself called immodest.10

Far more than sex, however, the main subject of Princess Charlotte’s education was politics, and if neither of her parents had much affection for her as a child, she was able to draw some emotional nourishment from the British people. She followed her father in her choice of party. The Prince of Wales had been a Whig for years, in part to distinguish himself from his own Tory father, George III. He supported the party that favored parliamentary reform, limited power for the monarchy, Catholic emancipation, and other progressive causes. But when, in 1811, the mind of the aged king finally succumbed to porphyria, his son became Regent, and with his accession to power he abandoned his former party. Charlotte found herself her father’s political opponent. She wrote to her friend Mercer Elphinstone of the intended switch: “When this is known in the world … how very unpopular it will make the Prince…. All these things must make all good wigs tremble–but not give up, as the motto must undoubtedly be perseverance.”11 The deficiency of her basic education shows itself in her lifelong spelling of the word as “wig.”

Charlotte’s position “England’s Hope” did not mean that she participated in political campaigns, as other women from aristocratic families did (this is discussed further in Chapter Four). Rather, she became powerful as a symbol of opposition: “[w]riting about the Regent’s oppression of his daughter became a way of writing about the government’s oppression of the people.”12 Charlotte’s political choices suddenly became very important to the rest of the country; her father, who was no fool, kept her as much as possible out of the public spotlight to minimize that importance. The young woman–at sixteen she was approaching marriageable age–was nearly a prisoner in the royal compounds.

A spunky one

Charles Williams’s 1816 etching Is Not She a Spunky One–or The Princess and the Bishop celebrates Charlotte’s famous flight after her father tried to force her to marry. Her elderly tutor, the Bishop of Exeter, is no match for her agility. Charlotte did not actually run to a ship, and was soon returned to Kensington Palace, but she held her ground and did finally marry for love. PFQRZHEIMER COLLECTION

Personally, the habit of opposition to her father became of the greatest use to her when it was proposed in 1814 that she marry William, Prince of Orange, heir to the newly created United Netherlands. The young prince was not unattractive, and he and Charlotte liked each other. On the strength of this, the match was made. Then she read the fine print in the marriage contract. Charlotte learned that if she married William she would be expected to spend at least half of each year in the Netherlands. This was too much for a patriotic Englishwoman, and Charlotte, with a strength of character that was the female equivalent of courage under fire, broke off the match.

This was not a simple or brief process, and the treatment she received from her father as she was trying to convince him that she could not go through with it was so unpleasant and pressure-filled that, at last, she ran away from home–that is, Warwick House–to her mother at Connaught House. The escapade lasted only about twelve hours; a train of court advisers, politicians, and attendants were sent to bring back the princess, among them the same bishop who had read Hannah More aloud to Charlotte a few years before. Her rebellion resulted in six months of exile from London; but the match was, finally, broken off.

A royal death

Unfortunately, Princess Charlotte’s love match with Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg was cut short by her death giving birth to a stillborn son. Beloved as an example of royal integrity and honesty, she was mourned throughout the United Kingdom in pictures, public signs, and instant biographies such as Thomas Green’s Memoirs of Her Late Royal Highness Charlotte Augusta of Wales, and of Saxe-Coburg (London, ca. 1817–18). PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Charlotte’s marriage to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg in 1816 required no heroics: although perfectly acceptable to the house of Hanover, it was also a love match. Charlotte and the very handsome German prince were unalloyedly happy, and her sudden death in November 1817, a few hours after giving birth to a stillborn son, threw England into public mourning of an unprecedented intensity. There were many sources for the grief: a young princess, a wife still in the first year of marriage, a happily expectant mother, all died at once. With the stillborn child, two heirs to the British crown, and the shining hope of the opposition, had been torn away at once.

Royal deaths are public business, with the power to arouse personal grief in everyone. The death of Charlotte was one of the most significant of the day in Britain. Her grandfather, George III, had been on the throne since 1760; both he and Queen Charlotte outlived their granddaughter. Her strength of mind had promised a great deal, and she had begun to tell the story of the virtuous wife in a new way, by showing that the good wife might have become a sympathetic royal politician.

A MOTHER: MARGARET KING MOORE, LADY MOUNT CASHELL (1771–1835)

In April 1818, in Pisa, on the coast of Tuscany, Margaret King Moore, titled Lady Mount Cashell and alias Mrs. Mason, wrote a letter for her daughters Nerina and Laura, then aged nine and three. It began “Ireland is my native land,” and told the story of her life in case the girls should be orphaned at an early age.13 The eldest daughter of a fabulously wealthy Irish aristocratic family, Margaret King had been “placed under the care of hirelings” from birth, and found the society of her parent’s house “not calculated to improve my good qualities or correct my faults.” Only one person of “superiour merit” had come within her circle, an “enthusiastic female” who was her governess when Margaret was fourteen to fifteen, for whom she “felt an unbounded admiration because her mind appeared more noble and her understanding more cultivated than any others I had known.” The governess, although she does not name her, was Mary Wollstonecraft.

Margaret had striven to continue the moral and mental improvement begun with this woman, although she still needed advice–more, perhaps, “than those who had less exalted views.”14 In the early years of her marriage, she was active in Irish politics, supporting Ireland’s freedom from British rule and Catholic emancipation from the prejudicial laws that kept Catholics from power in a country where they were the majority–despite the fact that she owed her wealth and privileges directly to these laws.

Keepsake for her daughters

In April 1818, Margaret King Moore, Lady Mount Cashell, left this letter to her daughters “in case Laura & Nerina should be left orphans.” In it, she described her life, attributing her unusual path to her beloved and strong-minded governess, Mary Wollstonecraft. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Margaret King had betrayed her exalted views in another way by marrying, according to her parents’ wishes, the son of another aristocratic Irish family. The marriage was unhappy, and grew more so with each passing year. Nonetheless, she bore eight children to Stephen Moore, the Earl of Mount Cashell, and stayed with him until 1807 when she left her husband and children for George Tighe and, eventually, an exile’s life in Italy. When she broke off her letter in 1818, she had another seventeen years to live, during which she never again saw Moore or many of the children from that first family. (Some, contrary to their father’s wishes, did make contact with their mother on her infrequent visits to England.)

Our immediate interest in Lady Mount Cashell begins with her life in Italy, which allows us to ask and answer the question: How does a woman live a virtuous life when her idea of virtue is radically different from that of the times to which she belongs? Lady Mount Cashell found that such a life was possible only through complete transformation: she had to give up her name, country, class, family, possessions, and language. In exchange, she was able to live with integrity and a considerable degree of freedom. Arguably, she made choices that were more courageous–certainly they were more painful–than those Mary Wollstonecraft had made; for while Wollstonecraft had been imbued with the hopes of the French Revolution, Lady Mount Cashell lived in the more authoritarian Napoleonic era. But where Wollstonecraft was original in almost everything she did or published, Lady Mount Cashell was, with a surprising degree of consciousness, carrying through her old governess’s vision. Her new name, Mrs. Mason, was taken straight from Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life–one of the neater turns of literary history, since the “real life” from which the original stories were drawn was that which Wollstonecraft had led in Ireland with the King family. The Mrs. Mason of the stories teaches two girls to do all the good they can in the present day, and there is little doubt that the Mrs. Mason of Pisa did the same.

The methods she found of doing good were superficially conventional. She wrote a book of advice to young mothers, composed stories for children, and translated medical treatises from the German. Her house became the local infirmary for the Italian peasants and laborers. Pedagogic writing and amateur medicine were, in themselves, normal occupations for genteel and aristocratic women. Her difference from conventional British philanthropical women was her level of expertise. While her girlhood education had emphasized the accomplishments–sewing, French, dancing, and so on–she was able to return to her studies as an adult, and, thanks to her wealth, had the time and leisure to occupy herself seriously with medicine. Mrs. Mason was rigorous, going to textbooks, rather than relying on the volumes of home remedies that were popular across Europe. Her Advice to Young Mothers on the Physical Education of Children remains a model of sensitivity and good sense. She observes, for instance, in regard to girls on the brink of puberty that:

at this period of their lives… uneasiness of mind is likely to occasion far more injury than drugs can ever remedy. The moral feelings are, often, too little considered, and the physical too much; for mothers who make no scruple of wounding a daughter’s sensibility, or mortifying her pride, will yet be very ready to cram her with pills or draughts, if she happens to look pale, or complain of a head-ache.15

This is good advice that any teenaged daughter today would still wish her mother to follow. Apparently Mrs. Mason was able to take her own advice with her two daughters by George Tighe, who were devoted to their mother, and she to them. But there was no “happily ever after” in her life. She had cast her lot with a kind and intelligent, but essentially solitary Irish gentleman.16 His chief interest was agronomy–he specialized in finding varieties of potato suited to Italian soil, and was nicknamed “Tatty.” Although united in their love for their daughters, their relationship cooled after a few years, and they lived separate lives in the same house.

“Do all the good you can”

This illustration by William Blake, from Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life (2nd ed., 1796), is captioned “Be calm, my child, remember that you must do all the good you can the present day.” Lady Mount Cashell renamed herself Mrs. Mason, after the stories’ protagonist, when she left her husband for a new life in Italy. There, she acted as physician and pharmacist to the Italian poor, taking Wollstonecraft’s philanthropic advice.

PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

The loss of the children of her first marriage was a bitter regret, and such a sacrifice is still difficult to comprehend, except by positing that her marriage to Stephen Moore must have been miserable indeed. She did believe that she was doing the best thing materially for her children, and their father, in any case, had every imaginable legal right over them. By a happy paradox, however, her exile allowed her to be of great service to Mary Wollstonecraft’s descendants, both physical and spiritual. When Wollstonecraft’s daughter, now Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, moved to Pisa in 1819 with her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and her stepsister Claire Clairmont, themselves exiled from respectable England, she carried a letter of introduction from her father to the former student of the mother she had lost at birth. (For more on Mary Shelley, see Chapter Five.) The link between the families had never quite been broken; Mrs. Mason had become friendly with Wollstonecraft’s widower, William Godwin, in 1807 in London, and the small publishing house run by Godwin’s second wife, Mary Jane, had put out her popular Stories of Old Daniel: or Tales of Wonder and Delight among other children’s books. The families in Pisa became fast friends, and Mrs. Mason gave aid and advice to the Shelleys. To Claire Clairmont, whose position as the unmarried mother of a daughter by Lord Byron was particularly difficult, she was especially sympathetic and helpful, and Clairmont remained in correspondence with the descendants of George Tighe and Margaret King Moore into the late 1870s, long after their deaths.

Irish patriot

As a young woman, Margaret King (later Lady Mount Cashell) was a passionate supporter of Irish freedom from English rule. She never lost her love for her native land, and in this hand-colored lithograph, from around 1833, when she was in her early sixties, she holds, as a talisman, her unpublished novel on Ireland. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

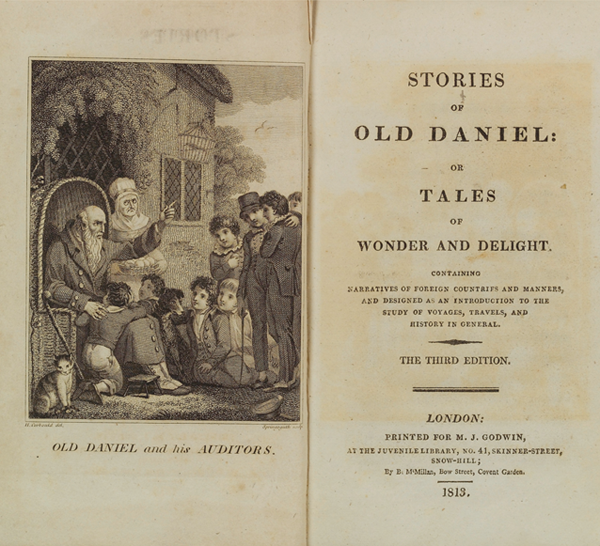

Tales of wonder and delight

Lady Mount Cashell’s Stories of Old Daniel: or Tales of Wonder and Delight (London, 1813) was a popular children’s book of the day, and carried on the Mount Cashell–Wollstonecraft connection: the publishers were Mary Wollstonecraft’s widower, William Godwin, and his second wife, Mary Jane Godwin. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Mrs. Mason, or Lady Mount Cashell, remained ambivalent about her choices and their high cost. She reflected in 1818, thinking of the early years after she had left Stephen Moore and her children, that “Misfortune must ever be the lot of those who transgress the laws of social life.”17 However, she found herself freer and, finally, “perfectly satisfied” in the hope–modest, and fulfilled–of spending the rest of her life “in that middle rank of life for which I always sighed when apparently destined to move in a higher sphere.”18

A WIFE: CAROLINE NORTON (1808–1877)

Caroline Sheridan, like Margaret King, married for money. But where Margaret King Moore escaped from an unhappy marriage by leaving the United Kingdom, Caroline Sheridan Norton stayed to fight. Chronologically, her life extends beyond the boundaries of this book, but her version of the story of the virtuous wife warrants a place for her, since its ambiguities are redolent of the end of the Romantic era and the beginning of the Victorian. While Lady Mount Cashell made her peace with a bad marriage by a private solution, Caroline Sheridan took the more modern course of changing the law. Three episodes in her life have a special claim on our attention: the adultery trial through which her husband, George Chapple Norton, dragged her and her friend Lord Melbourne, and the two political struggles that led to the passage of the Infant Custody Bill in 1839, and the Marriage Act of 1857.

From the beginning, the Nortons were ill-matched. At the time they married, in 1827, George Norton was a conservative Tory Member of Parliament. Caroline Sheridan had grown up in a household of inherited liberal politics. Her grandfather, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who gave Mary Robinson her start on the stage, had also been one of the leading Whig politicians of his day. But the three handsome Sheridan sisters inherited little but artistic glory and good after-dinner stories from their witty and charming grandfather. They came, however, from too good a family to open a school as the More sisters had; they needed to find husbands.

George Norton appeared in Caroline Sheridan’s world wholly by chance. Still a schoolgirl, she was taken on a tour of his brother’s stately home at Wonersh, in Surrey. There she met Norton’s sister, and was invited to return. The girl hardly noticed Norton on her visits; they were not even introduced, but he fell in love with her and wrote a letter of proposal to her mother. It was refused–Caroline Sheridan was only sixteen–but he did not forget her. And after she had been through two London seasons without finding a hus-band, Sheridan accepted George Norton’s renewed offer of marriage out of deference to her mother and desperation at the thought of being left a spinster.

A genteel crusader

In this portrait from English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (London, 1854), Caroline Norton looks pensive and serene; the depiction is completely at odds with the real life of a woman who, deprived by English statutes of any contact with her sons, vowed to change the law–and succeeded. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Soon after they married, Norton cajoled Caroline’s mother into finding him a sinecure with the government; although a barrister, he was also the heir of the estate at Wonersh, and refused to work as it was unbecoming to a gentleman. (Parliament was at this time a fine job for such a gentleman since Members were not remunerated.) This was a bad beginning, and things grew worse: he had misled his new wife and her family as to the amount of his income, and within six months of marriage he began to beat her. Norton’s abuse followed a still-familiar pattern: he would assault Caroline, then apologize abjectly and promise to reform. The law was almost useless: separations were possible, but divorce was not, except by an expensive and hard-to-obtain private act of Parliament. As we have seen, all property rights of married couples rested with the husband, and all parental rights rested with the father.

The Nortons were, nonetheless, a fashionable London couple in their public hours. Caroline Norton found comfort and distraction in society, and pursued it energetically in the late 1820s and 30s. Before marriage she had been seen, along with her sisters, as slightly coarse: “The Sheridans are much admired but are strange girls, swear and say all sorts of things to make men laugh.”19 Even after marriage she enjoyed flirtation–despite its being, as she discovered, a very dangerous game, it offered one of the few opportunities a genteel woman had to take risks or simply to play as an adult. The Nortons became friends with William Lamb, Lord Melbourne, one of the leading political figures in Britain and a Whig. Caroline Norton became especially close to him. George encouraged the friendship in the hopes of political patronage, which were fulfilled by a minor government position.

Meanwhile, Caroline Norton had begun to write poetry and novels, and gave birth to three sons. Her life was characterized by the painful duplicity common in the lives of battered women, in which to all appearances she led a normal, indeed highly successful life, while living a nightmare of uncertainty and pain at home. Everything came to a head in the spring and summer of 1836 when George Norton first left his wife, taking the three boys with him, and then instituted a suit for criminal conversation–that is, adultery–against her and Lord Melbourne, who was then the Whig Prime Minister. It threatened to bring down the government, which could not have withstood the scandal, and this may have been a factor in Norton’s decision to bring the suit at that moment. But George Norton lost resoundingly. He had no evidence except the suborned word of some servants who had been fired years before. Moreover, Caroline Norton’s lawyer delivered a scathing speech in which he exploded all of the testimony that had been offered. The jury did not even need to leave the jury box to come to its decision.

This would seem to have been a happy ending: the wife proven virtuous, the husband a cad, she should now have been able to get on somehow with her life. But Caroline Norton’s life was transformed for the worse by the victory. Norton’s loss meant that the couple could not be divorced, since the wife’s adultery was the only ground acceptable to the law. And as Caroline Norton was to discover, the lawsuit had ruined her reputation. Not everyone believed the jury’s verdict, and even if she had not slept with Melbourne, her acquaintance with him had reached a level of intimacy that was not acceptable for a married woman, even one whose husband was generally acknowledged to be a monster. A “ruined reputation,” however, did not mean that Caroline Norton was permanently shunned by the fashionable society she loved, although she stayed aloof from it for several years. When she returned, her reception was politicized–Whig households took her in, Tories did not. Lord Melbourne was, understandably, reluctant to see the woman who had unintentionally damaged his political career.

Caroline Norton had, however, unambiguously lost the protection from slander that other women had. More than two years after the suit, for instance, the Crim. Con. Gazette published a character sketch titled “The Right Hon. Lord Melbourne,” putting forth embarrassingly explicit sexual metaphors implicating Lord Melbourne and Mrs. Norton. And the writer asserted what had become a commonplace: “it is not sufficient to be virtuous” to maintain a spotless character. Women must also “cautiously avoid the very suspicion of being [thought] otherwise.”20 There is nothing new in this. The idea that really virtuous women must not even be, as it were, suspected of being suspicious goes back to classical Rome. But two important things had changed in the early years of the nineteenth century. The first was that Caroline Norton’s shame was cast broadly by the gutter press: the Crim. Con. Gazette cost two pence and was aimed at a wide audience who would have known “the Honourable Mrs. Norton” as one in a panoply of public characters, someone whose poetry they had perhaps read in a Christmas annual.

The second innovation was that Caroline Norton was not going to allow the Crim. Con. Gazette or any other instrument of shame or embarrassment to stop her when her husband had injured her in the most painful way possible. The Nortons had separated informally after the suit, but George Norton had retained custody of their three boys. For a time he allowed his wife to visit them, but the enmity between them led him to bar all contact between the mother and children, as was his right. Like Mary Wollstonecraft, Norton fought back. But where Mary Wollstonecraft had fought in the same way that men did, through writing works of passionately reasoned political theory, Caroline Norton made the fight personal and she made it feminine. Unlike Wollstonecraft, she also managed to change the law. Norton put all of her political and publishing connections to work. She appealed to her friends in Parliament and wrote impassioned pamphlets in which she drew extensively and eloquently from her personal experiences. And in 1839 the passage of the Infant Custody Act, sponsored by Norton’s friend Thomas Noon Talfourd, gave married women custody of young children.

But as in the life of Lady Mount Cashell, there was no happy ending for Caroline Norton. Norton’s parliamentary lobbying was so far from disinterested that it hardly seems to have occurred to her that other women might also have been cruelly deprived of their children. Soon after Talfourd first proposed the Infant Custody Bill to Parliament, a partial reconciliation was effected between the Nortons, in which he agreed to let her have the children at times. Caroline Norton’s constant pushing for the act suddenly ended, and Talfourd, who had been acting largely as a favor to her, let the bill lapse. When the reconciliation (unsurprisingly) fell apart, and George Norton once again refused to allow Caroline to see the boys, Talfourd reintroduced it at the next session of Parliament. The delay was seen as directly owing to Caroline Norton’s selfishness.21 In the event, the passage of the bill was useless to Norton; George Norton promptly took the boys to Scotland, where it did not have effect. Only when one of them had died from lockjaw after a fall from his pony did he relent and establish a regular visiting schedule.

Upper-crust affairs

For centuries “crim. con.” was slang for the legal term “criminal conversation”–that is, adultery. Crim. con. trial transcripts, describing scandals of the rich and famous, were popular reading matter for decades. The Crim. Con. Gazette, by contrast, was not bound to accuracy, and could indulge in purely speculative gossip, as here, in a November 10, 1838, column devoted to Caroline Norton and then Prime Minister Lord Melbourne. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Caroline Norton’s selfish mode of operating is indisputable. But if we look at some of her other actions we can see a new, distinctly Victorian, way of using femininity for political ends. Four years before the Infant Custody Bill was introduced, Norton supported the 1832 Reform Act by sending charming and flirtatious letters to Members of Parliament.22 While the Reform Act–which broadened Britain’s voting base enormously, and cleared up a great deal of political corruption–was a Whig cause, Norton could not have hoped to benefit from it personally. When she wrote “A Voice from the Factories” (1839), the first of what became a sub-genre of sentimental protests against child labor, her motivation was not merely her own enrichment. And when, as a favor to her friend Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, she pulled strings to have William Godwin’s pension continued after death for his widow, she was certainly not doing it for personal gain.

Caroline Norton in middle age

After years of separation from her husband, Caroline Norton had a brief but happy second marriage before her death in 1877. By then the laws that had made her life so difficult had largely been reformed. This photograph shows her around1862. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Caroline Norton never fully absorbed the stories of good girls. She was able to tell the story of female virtue in a way that was both new and old: old in its dependence on feminine charms and personal attachments (methods that Mary Wollstonecraft had despised), and new in its aims, which were practical, wide-ranging, and permanent. The pragmatic advantages and ideological drawbacks of her method are shown again in the passage of the act that revolutionized divorce proceedings, and significantly affected married women’s property, in 1855.

This time, Caroline Norton had political competition from other women, among them Harriet Martineau, Jane Carlyle, George Eliot, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, all of whom had signed one of the seventy petitions circulated across Britain in favor of the Married Women’s Property Bill, which would have given married women’s property the same legal status as that of single women. As the law stood, a husband had all rights to his wife’s property (unless it had been protected in a trust), her earnings, and potential earnings. George Norton had used this as grounds to refuse to pay Caroline Norton the allowance he had settled on her after their separation, since through her writing she was able to earn substantial sums that he generously allowed her to retain. Her solution this time was both personal and public: she wrote a review of all the laws pertaining to women, but also wrote letters vindicating herself (only) to the Times, and published other pamphlets based on her experience as a wronged woman, one of them framed as a letter to Queen Victoria.

But she did not write, as the other women had, a new bill. Rather, she focused her attention on a bill already making its way through Parliament that would reform the divorce laws, and offered amendments to it largely aimed at protecting the property of separated women. The Married Women’s Property Bill would have effected a far deeper and more thorough reform than what Norton had proposed. It is impossible to say whether or not it would have passed, since it did not come to a vote, and it was not for another decade that such a bill did pass. Meanwhile, some of the reforms that Caroline Norton had proposed–including protections for the earnings of deserted wives, and for inheritances by married women–were included in the divorce bill. They were a smaller step forward but a genuine change for the better.

What conclusions can we draw, then, about female virtue in these years? How was “being good” different then? These stories make clear that for many women, being good meant suffering: enduring the pain and dangers of childbirth, bearing the frustrations of an unloving marriage, and living with a law framed to protect men’s property–all were seen as necessary to the production of good wives and mothers. Social change came from those who refused to see female suffering as a necessity. In this chapter we have seen a daughter’s adolescent rebellion against her father succeed by the very traditional tactic of marriage; a mother’s private combat against social rules, won at a terrible price; and the protracted, miserable war of a fierce wife and mother against a husband and the statutes of England. A broader range of women will be presented next: those who, for many different reasons, paid considerably less attention than Princess Charlotte, Margaret King Moore, or Caroline Norton did to the demands of virtue.