THE PREVIOUS CHAPTER looked at women who tried, with varying degrees of success, to live according to the conventions of their time and to be what the Victorians would come to speak of as “proper ladies.” This chapter will look at a group of women who were, in the public view, decidedly improper.

ARISTOCRATIC AMATEURS: GAMBLERS AND POLITICOS

The prominence of gambling in British life during the Romantic era is often forgotten, and it was by no means limited to the rich. But it was seen as a particular vice of the wealthy, who had money to throw away. Hannah More and Mary Wollstonecraft both disapproved of this “form of luxury,” which was “geared not toward the display of wealth but to the display of one’s insouciance in losing it,” and they were far from alone in seeing gaming as an obscene waste.1 Georgiana Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire, the early patron of Mary Robinson, lost the modern equivalent of over $10 million in a few months, and although she may have reacted with public insouciance, she was privately tortured by the loss. She was addicted to gambling, and lost to an extent that threatened her marriage.2 For women there was an extra risk in gambling that did not exist for men: the possibility that one might be called upon to pay a debt with sexual favors instead of money. The Duchess escaped this fate, but it rightly inspired fear.

Some women, however, made the odds work in their favor. The popular game of faro (so called from the image of a pharaoh that appeared on one of the cards) was easily turned to the advantage of the banker, and regulations against private gaming were rarely enforced. Thus it happened that the Honorable Mrs. Albinia Hobart (1738–1816), later the Countess of Buckinghamshire, along with her friend Lady Archer, was herself the banker for a faro table.3 In 1797 Mrs. Hobart was convicted of gaming and fined £50, then thought a lenient sentence. The Chief Justice, Lord Kenyon, had threatened even noble gamesters with the pillory, and it was widely believed that she had embezzled from her own bank. Neither verbal nor visual satirists spared her: Mary Robinson, who had been part of the circle at Mrs. Hobart’s table, whipped her with words in her novel Walsingham (1797). James Gillray’s cartoon from the same year (see page 59) shows Mrs. Hobart whipped and tied to the back of a cart–an unkind image even in an age that delighted in cruel caricatures.

The faro tables brought forth a number of images of women indulging in excess: in the midst of “deep play” (that is, for high stakes) they are shown either as uncontrollable as gamesters, or as too powerful as bankers. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, as the standards of public behavior became stricter and the sight of women gambling for large sums became unpalatable, the practice diminished and the figure of the haggard woman in a silk gown, her powdered hair disheveled from her sitting up all night, staking the last farm of her husband’s estate on a single card, faded from memory.

Ignoring the lecher

Britons of all classes and sexes loved gambling, although moralizers on both the left and right decried it. For aristocratic women, being expected to pay “debts of honor” with sexual favors was a real danger–or a viable option, depending on one’s point of view. In Lady Godina’s Rout–or–Peeping-Tom Spying Out Pope-Joan (1796), James Gillray’s young woman seems intent on ignoring the lecher at her shoulder. PRINT COLLECTION

An aristocrat in chains

In 1797 the Honorable Mrs. Albinia Hobart, later the Countess of Buckinghamshire, was convicted of gaming and fined £50, a lenient sentence. The Chief Justice, Lord Kenyon, had earlier threatened the pillory, and it was widely believed that she was also an embezzler. Neither verbal nor visual satirists spared her, least of all James Gillray, who in his Discipline à la Kenyon shows Mrs. Hobart whipped and tied to the back of a cart. PRINT COLLECTION

Aristocratic women did engage in more productive pursuits than throwing away their children’s inheritances, and politics was one of them. It was just as dirty a game as any cardsharper played, except that buying and selling votes, and conducting campaigns by any means necessary, were the standard behavior, not the deviation. Before the 1832 Reform Bill, seats in Parliament often went to those who could buy them. Voting lasted for days, and ballots were not secret. Because of the tiny voting base (all male, and mostly landowners or well-to-do citizens), it was often feasible for candidates to visit all voters, to hold dinners for them, and to buy them beer and ale in large quantities.

The participation of women from families of Members of Parliament was traditional, and for artisan or yeoman-farmer voters, seeing the women of their local gentry for once trying to curry favor with them could be quite seductive.4 But this participation also extended to non-family members, and women from the gentry up to the highest social ranks often campaigned for candidates for Parliament. Hannah More herself, in 1774, supported Edmund Burke when he was standing in the election as MP (Member of Parliament) for Bristol, though this support was limited to writing promotional pieces and presenting him with a celebratory cockade: she did not campaign publicly for him.

Despite the long tradition, conservative moralists such as More found it difficult to countenance women’s public political activities. The conflict was epitomized by women’s participation in the 1784 election for Westminster, an area of Greater London with an unusually large electorate. The prominent Whig politician Charles James Fox ran for one of the two seats against Sir Cecil Wray and Admiral Hood, and was aided by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. It was no surprise that she would campaign for Fox; Devonshire House, her London residence, functioned as the unofficial headquarters for the Whigs, and the Duchess herself was their mentor, facilitator, patron, and friend. In 1784 she was joined by dozens of other women from aristocratic families. Fox’s main opponent, Sir Cecil Wray, had the energetic Mrs. Hobart and a host of other Tory women on his side.

The campaign had national, not just local, importance, since Fox needed to win Westminster to retain control of Parliament. However, the press needs to put complex matters simply, and especially in the satirical prints–more than 300 were published–the contest was reduced to a sexual competition between Mrs. Hobart and the Duchess. The majority of the prints were against the Duchess, since they were paid for by the opposing side, and they slanted the misogynist view in many directions; Georgiana herself was made sick with despair. Hannah More infantilized her, writing to a friend: “I wish her [i.e., the Duchess’s] husband wou’d lock her up or take away her Shoes, or put her in a Corner or bestow on her some other punishment fit for naughty Children. All the windows are filled with Prints of her, some only ludicrous, others I am told seriously offensive.”5 Thomas Rowlandson’s print The Poll (see page 61), showing Georgiana and Mrs. Hobart on a phallic seesaw, counts as both “ludicrous” and “seriously offensive.” More’s wish that the Duchess be shut up did not prevail, however, and Fox was victorious. The stir created by the Duchess of Devonshire was probably a substantial help in getting him elected, despite–or because of–the prints plastered on shop windows. Campaigning became more decorous in the early Victorian period, and although women did not have the vote in Britain until after the First World War, they never completely retired from politics.

Dirty politics

Thomas Rowlandson’s The Poll memorializes the political activities of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and Mrs. Albinia Hobart, in the 1784 election for the Westminster seat in Parliament. (Another campaigner in this election, the Countess of Salisbury, is depicted on page x above as the goddess Diana.) As in many other satirical prints of the time, the political contest was reduced to a sexual competition between Mrs. Hobart (left) and the Duchess (right), shown here, for maximum offense, on a phallic seesaw. PRINT COLLECTION

ADULTERESSES

The most disturbing social errors were those that women tried to keep most private. Female sexuality in the Romantic period was a significant source of interest and anxiety. The “Modern Venus” (facing page) is based on a shameful incident of the earlier eighteenth century, when an African woman called by the English “the Hottentot Venus” was captured and exhibited to Britons. The image combines satire of the push-up fashions of 1786 with the implication that women, underneath it all, are only definable through their sexuality.

This exaggeration had its roots in the fear that the old sexual mores were breaking down, and there was some grounding for it: marriage ages had dropped over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and illegitimacy rates were rising, partly because of a new emphasis on romantic love and partly because of a new view of marriage as a loving, though unequal, companionate partnership.6 Older traditions, going far back in British history, were nonetheless still very strong. The logic behind them is clear: in nations with legal systems based on the eldest son’s inheritance (primogeniture), it is crucial to know that the putative father is the right one, or the property may go to a bastard. Thus laws regarding adultery and illegitimacy were much more important in daily life than they are now, and the figures described below lived, on the whole, by the double standard according to which women may not have sex outside of marriage while men, on the whole, can do what they like. The paradox of this arrangement was that rich and aristocratic women, as long as they kept their affairs and illegitimate children very few and very quiet, might have a degree of sexual freedom that was not available to women of the middle classes. Working-class women, who did not have to worry about passing on property, also sometimes had greater freedom in their choice of husbands or lovers than their genteel middle-class neighbors.

A new “Hottentot Venus”

Female sexuality in the Romantic period was a significant source of interest and anxiety. A Modern Venus, or a Lady of the Present Fashion in the State of Nature (1786), based on sketches by a Miss Hoare, has its roots in a shameful incident of the earlier eighteenth century when an African woman called by the English “the Hottentot Venus” was exhibited to Britons. The image combines satire of the pouter pigeon dress styles with the implication that women, underneath it all, are definable only through their sexuality.PRINT COLLECTION

Menage à trois The beautiful and wealthy Duchess of Devonshire–portrayed here with her sister, the Viscountess Duncannon–lived in a sort of ménage à trois with her husband and his mistress, Lady Elizabeth Foster (above, right), who was first her dearest friend and their children’s governess. Secretly, the Duchess conducted affairs of her own. Her Grace the Duchess of Devonshire and Viscountess Duncannon, engraving by W. Dickinson, after Angelica Kauffmann, 1782. PRINT COLLECTION; Lady Elizabeth Foster, engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, after Joshua Reynolds, 1787. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Sexuality was not in these days an easy thing to talk about: the shame often associated with the Victorian period was perhaps even stronger in the Romantic period. The difference was that prudery was not yet completely institutionalized: no one was comfortable talking about sex, but a great many people enjoyed making jokes about it. In these days, “common sense” said that women as well as men were highly sexual creatures. Many of the women in this chapter would have made bawdy jokes, and such jokes might have been made about some of them–though rarely is sexuality presented so purely as a form of amusement as it is in the two pictures reproduced on page 66.

Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (1757–1806)

_____________________________________________________________

Marriage for love, even among the aristocracy, had become desirable by the time Georgiana Spencer married William Cavendish, the fifth Duke of Devonshire, in 1774. But where riches were at stake, marriage for love was not always possible, and the older norm of tolerated philandering survived for aristocratic ladies longer than it did for other women.

For men, the survival was much more robust. Here, again, the life of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, is instructive. The Duchess brought Lady Elizabeth Foster (1758–1824) into her household as a governess. Although titled, Foster was separated from her husband and had almost no income of her own.7 She and Georgiana were already intimate friends–“romantic friends,” as their kind of relationship would later be called, meaning something between a sexual and platonic female relationship–and the hiring was a matter of kindness as much as need. Remarkably, the friendship survived even when Elizabeth Foster became the mistress to the Duke of Devonshire; the two women became allies, and he remained attached to both of them. The arrangement was difficult, especially at the beginning, and was a constant source of pain to Georgiana’s mother and children. The two women shared an affection that formed, along with their bonds with their children, the emotional core of their lives.

Few women–and even fewer husbands of unfaithful wives–were so tolerant as the Duchess of Devonshire. While she was willing to share her house with her husband’s mistress, she did not reveal to him her own extramarital affairs, and Foster helped Georgiana to conceal a pregnancy by a lover of her own. Elizabeth Foster became a permanent fixture in the household, and the ménage à trois lasted from 1782 until Georgiana’s death in 1806, after which Foster became the next Duchess, to the consternation of the whole family–except, of course, the Duke.

The privacy of home

Adam Buck’s Serena (1799) and the anonymous Comfort (1815) portray women’s sexuality as a subject for comedy. Over the course of the nineteenth century, this kind of jocularity became less and less acceptable in public venues. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Princess, later Queen, Caroline (1768–1821)

__________________________________________

Beyond a doubt, the poster child of adulteresses in the Romantic era is Princess Charlotte’s mother, Princess and later Queen Caroline, an extraordinary woman in a number of ways. The “Delicate Investigation” of 1806, described briefly on pages 40–41, first opened the possibility that Caroline might have committed adultery. Her innocence was declared but her character was besmirched by her undignified, unruly, and simply peculiar behavior: adopting children who might or might not have been hers, writing anonymous obscene letters to her enemies, entertaining gentlemen alone; none of this was acceptable behavior for the future queen of England. In 1814, after a formal separation had taken place, Princess Caroline left the country. She was on the road for seven years, and while her husband continued to keep mistresses in his habitual expensive style, Caroline, too, did not restrain herself. She went as far as Jerusalem, which she entered in the company of her devoted servant, Bartolomeo Bergami. The satirists could not resist the joke on Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem and portrayed her on a donkey, her always-fleshy body now appearing to strain the animal’s back (see page 69).

When George III died in early 1820, and the Prince of Wales, Regent for the previous nine years, finally became king, she returned to claim her due. She was presented with divorce proceedings, in the form of a “Bill of Pains and Penalties” accusing her of adultery. Transcripts of divorce and criminal conversation trials were popular licentious reading in these years. The Crim. Con. Gazette, in which Lord Melbourne and Mrs. Norton were seen pilloried in the last chapter, was the heir to the genre. The trial transcripts enjoyed huge sales both singly and in bound sets. George IV was not only a legendarily unfaithful husband, he was an extraordinarily unpopular king. Just as the defense of his daughter, Princess Charlotte, had been a way of promoting oppositional politics, so, too, was the defense of Queen Caroline, as radicals across the country proclaimed her innocence. Her defenders were, on the whole, well aware of her guilt, but the trial was so politicized that for many this was simply not the point. Her trial divided the country, and the failure of the proceedings was greeted with acclaim.

Caroline’s role in the political fracas that surrounded her return from abroad was largely to allow herself to be made a symbol. The final battle–which she lost–came when George IV locked her out of Westminster Abbey during his coronation. Since she was legally his wife and technically innocent, there was no reason for this beyond his inveterate dislike of her. Before the event, respectable ladies registered their support of the queen by discreet processions of private carriages. Women and men of all classes and from all areas of Britain signed petitions in the same cause, and provide a glimpse of one kind of political action undertaken by those who did not have the vote.8 When she died in 1821, just a month after the coronation, the public outpouring of grief was nearly as extensive as it had been at the death of Princess Charlotte.9

Versions of a queen

Princess Caroline, wife to the Prince of Wales, was acquitted of adultery charges but lived much of her life in continental Europe, far from her very unloving husband. At the death of King George III, she returned to claim her title as queen only to find herself locked out of the coronation ceremonies by her husband–now George IV. A political lightning rod, she attracted both support and opprobrium. Thus the liberal George Cruikshank portrayed her around 1820 as a dignified older woman, while Thomas Jonathan Wooler’s satirical pamphlet The Kettle Abusing the Pot (London, 1820) argues that her husband’s sins are the equal of hers. On the anti-Caroline side are two scenes from travels with Bartolomeo Bergami, her courier and lover: an illustration from the anonymous New Pilgrim’s Progress (London, 1820) embarrassingly depicts her in the bath with Bergami pouring hot water, while Theodore Lane’s A Gentle Jog into Jerusalem (1821) shows Caroline on a donkey. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Harriet Shelley (1795–1816)

__________________________

If Queen Caroline very publicly made the case for the erring wife who gains sympathy because her husband’s sins are so much greater than her own, Harriet Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s first wife, did the same thing on a very private scale. Deserted by Shelley and pregnant by another man, she died by drowning herself in Hyde Park.10 On her own account, she hardly deserves the epithet “extraordinary”: Harriet Westbrook Shelley seems to have been a sweet, passive young woman who clung to stronger personalities. The aftermath of her death illustrates what had become a primary response to respectable women who became pregnant outside of marriage: they were victims.

Her story is brief and melancholy. Harriet Shelley’s husband left her in 1814 after he fell in love with Mary Godwin, daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Harriet was only nineteen, and apparently was taken entirely by surprise when she was deserted.11 The little correspondence that we have from her between 1814 and her death is depressed; she began, as well, to spread rumors that Godwin had sold his daughter to P. B. Shelley. She left behind two children by Shelley, and was heavily pregnant with another man’s child at the time of her death. At the coroner’s inquest, her landlady’s maidservant reported that she had seen “nothing but what was proper in her Conduct with the exception of a continual lowness of Spirits.”12

Harriet Shelley left a suicide note but did not mention her pregnancy, writing instead: “why should I drag on a miserable existence embittered by past recollections & not one ray of hope to rest on for the future.”13 While the public press could be venomous in its attacks, it could also be protective, and in this case it was. When Frances Imlay Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft’s daughter by Gilbert Imlay, killed herself by an overdose of laudanum at an inn in Swansea shortly before Harriet Shelley’s death, her identity too was protected by the law and the press. In both cases the women were portrayed as the antithesis of the lustful woman: they were victims, a pathetic stereotype that became ever more prevalent in the Romantic period; by the time Victoria reached the throne, it was the standard way to speak of errant young women, not only those from middle-class families but working-class women as well, including the ones who turned to prostitution. The image of the victim allowed respectable men and women to feel pity for prostitutes, and also strengthened the still-novel idea that proper women were naturally mothers and should not enjoy sex.

Male treachery, real and fictitious

“Why should I drag on a miserable existence embittered by past recollections & not one ray of hope to rest on for the future.”–so wrote Harriet Westbrook Shelley in the suicide note she left on December 7, 1816, before drowning herself in Hyde Park. The first wife to the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Harriet became pregnant by another man after her husband deserted her. The press portrayed her as a pathetic victim, a stereotype that became ever more important in the Romantic period, as the unattributed novel Domestic Misery, or The Victim of Seduction (London, 1802)–one of many of its kind–attests. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Prostitutes as victims

Thomas Rowlandson’s The Last Shift, depicting a young prostitute at the pawnbroker’s, uses an old pun–a “shift” was a slip or petticoat that one might pawn for a few pence, but a “last shift” was also a “last resort.” In both cases the emphasis is on the prostitute as victim of society, although this young woman looks rather cheerful. PRINT COLLECTION

Prostitutes as predators

The traditional presentation of prostitutes as greedy and deceitful was also still viable in the Romantic period, especially in conjunction with other stereotypes, such as this anti-Semitic portrayal of a Jew in Thomas Rowlandson’s Ladies Trading on Their Own Bottom (ca. 1810). PRINT COLLECTION

COURTESANS

Some women conducted active sexual lives outside of marriage but refused the label of victim. Courtesans were first among them. Being a courtesan was a more complicated matter than it might seem at first blush: courtesans were usually attached to one man (though they might change men quite often), from whom they often received a fixed allowance. It did mean, however, that one lived as an unabashedly sexual creature, and the lower down the economic scale one found oneself, the more unabashed one had to be. Outright prostitutes, such as the women shown here in a print that panders to both the misogynist and anti-Semitic strains of British culture, would gather in certain areas of London, and accost by voice and by touch all male passers-by.

Yet courtesans were not shameless. On the contrary, they made genteel men comfortable because they were not totally unlike the women the men knew in their aboveboard social worlds. Courtesans lived just over the boundary of respectability, and while many stayed on the disreputable side, a few were able, even as the boundary became harder to cross, to transform themselves into wives.

Harriette Wilson (1786–1845)

___________________________

Harriette Wilson, one of the most successful courtesans, parlayed her sexual history into a bestseller: the Memoirs of Harriette Wilson went through thirty-five editions in the first year of publication. It constitutes one of the rare pieces of blackmail that might also be called charming. Wilson’s success began with her talent for writing: she sometimes found keepers–as men who supported mistresses were called–by introducing herself to men through impudent but seductive notes. This was only at the precocious beginning of her career; once launched, she was, for years, in the keeping of one man or another, gadding about from the newly fashionable beach resort of Brighton, down to London, over to the Continent. She was beautiful, but more important, she had the two requisite skills of a courtesan: she was good company and she liked sex. Many of her lovers were aristocrats or important politicians. Thus, when the time came to write her memoirs, she had a string of well-known names and addresses.

Wilson’s publisher, John Joseph Stockdale (whose private life took the same evangelical path that Hannah More’s did), hit on an ingenious method of bringing out the Memoirs: they were published in parts, with a new installment each month.14 This offered Wilson time to negotiate with–that is, blackmail–the men whose names and adventures were about to be made public. Generally she asked for an annuity of £20 to £40, or a lump sum of £200, in return for which she would refrain from naming their names. Some men bargained; some paid; some, as the Duke of Wellington is said to have done, replied “Write and be damned!”15 Ultimately, Wellington’s was the sensible position, since for men willing to wait out the gossip there was no lasting social penalty. But men as well as women knew what shame was, and when it is difficult to talk about sex in a serious way, it is easy to talk about it in a damaging way.

The tactful mistress

The courtesan Harriette Wilson blackmailed former lovers–many of them rich and respectable–who wanted to keep their names out of her Memoirs (London, 1825), which was issued in installments, giving her time to negotiate. Even when she named names, however, she was suggestive rather than graphic, an oversight some of her illustrators tried to address with racy pictures, such as the one reproduced here. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Wilson did publish, and her Memoirs sold–and sold, and then sold some more. There was no copyright protection for works such as hers, and the pirate publishers who flourished in those years started printing cheap versions of the Memoirs as soon as they could. Besides pirates, libel suits might have been the great danger. Finally, however, none of the men named wanted to exacerbate the publicity or rehearse sordid tales in court by suing.

Suing would have been particularly self-defeating because Wilson’s accounts are by no means explicit. Sex sold the Memoirs, but Harriette Wilson’s business was to tease, and she omitted all details on her lovers’ styles or activities in bed.16 She relied instead on an insouciant, thoroughly disarming style, opening her book, for instance: “I shall not say why and how I became, at the age of fifteen, the mistress of the Earl of Craven. Whether it was love, or the severity of my father, the depravity of my own heart or the winning arts of the noble Lord … does not now much signify; or if it does, I am not in the humor to gratify curiosity in this manner.”17

Insouciance was the appearance Wilson tried to give her whole life. She was not used to saving, and rapidly fell afoul of one of the most serious and now nearly forgotten plagues of the Romantic period (and long before): debt. It was easy to find oneself arrested for debts, even small ones, and difficult to get out of prison. Wilson eventually availed herself of the most effective way to avoid debtors’ prison, which was to move to France. She died alone in Paris, abandoned by the man she had called her husband. But she did not die quite forgotten, and her fundamental good nature allowed her to count on a certain amount of affection from some unlikely candidates. In one of her last letters, she asked a former lover, the politician Henry Brougham, now in the House of Lords, to pay for her funeral, along with the Dukes of Leinster and Beaufort. All of them had at one time paid her hush money, but she hoped they would let bygones be bygones. She had totted up the costs of her very modest interment and threw herself on their goodwill. And she was right: one last time, for a now permanently silent Harriette Wilson, they paid.

Emma Hamilton’s lithe youth

As the mistress of Sir William Hamilton, Emma Hart became famous for her “attitudes,” in which she posed as figures drawn from classical art and mythology–here she is a Bacchante, a frenzied female worshipper of Bacchus, the god of wine. Engraving by Tommaso Piroli, after Frederick Rehberg, from Drawings Faithfully Copied from Nature at Naples (Rome, 1794). PRINT COLLECTION

A gift for theater

By 1801 Emma had become Lady Hamilton; she was now also the rather ample mistress of her husband’s great friend, Horatio, Lord Nelson. In Dido in Despair! (1801), James Gillray attacked her melodramatic tendencies, taking the opportunity to show off his particular talent for drawing hands. PRINT COLLECTION

Emma Hamilton (1761?–1815)

__________________________

Emma Hamilton, most famous of all the mistresses of the period, crossed into respectability without giving up her fondness for public performance, and her paradoxical position has fascinated readers ever since. Making multiple transformations of her life, she became a wife, a mistress, and, not least, a series of theatrical presentations known as “attitudes.” Born Amy Lyon, she grew up in Wales, nearly illiterate and very beautiful. It seems likely that she spent some time as a prostitute in London, but one of the secrets of her later self-transformation was that she did not discuss her youth, and while rumors abounded, she did not respond to them. However, by twenty-one she had become the mistress to a young politician named Charles Greville, second son to the Earl of Warwick. Greville had fallen into debt, and Emma helped him to economize, keeping house for him in a quiet part of London. She had a daughter and strove to improve her education. Greville’s friend, the celebrated portraitist George Romney, who adored her chastely, painted her often. As lives of sin go, it was retired and peaceful.

Greville, however, dreamed of finding an heiress to marry, and Emma Hart–as she was now called–was an impediment to this goal. His tasteless solution was to offer her to his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, the British ambassador to Naples, in hopes that providing him with a mistress who was beautiful, faithful, and highly domesticated would influence him in his money-lending capacities. It was crass, but proved a correct calculation.

Greville had not factored in the possibility that the relationship between Emma and his uncle might one day include love. Emma met Sir William in 1784, and went to Naples in 1786, horrified, at first, to discover that he expected her to become his mistress. Greville encouraged her, however, and she eventually gave in. She married Hamilton in 1791. Greville, who never did capture his heiress, found some help forthcoming from his uncle. Meanwhile, Emma had effected an Eliza Doolittle–like transformation in real life. She learned Italian and took singing lessons for a voice that turned out to be extraordinarily beautiful. After her marriage she was introduced into Neapolitan and British society. She became intimate with the queen of Naples, an important figure in the sticky web of diplomacy during the Napoleonic Wars, and used her friendship to promote British interests in Italy. She learned how to entertain on a large scale and how to charm very different kinds of people. Amy Lyon had become Lady Hamilton, a diplomatic wife.

She had also begun to enthrall Sir William and his guests with her famous “attitudes.” To “take an attitude” was to strike a dramatic pose derived from a work of art, and those Emma took on were often imitations of figures from the Greek and Roman sculptures, coins, and vases that Sir William loved. (Many wealthy Englishmen collected such objects in these years, and Hamilton’s collection was legendary.) The attitudes were admired for nearly the rest of her life, for “notwithstanding her enormous size,” she continued to perform them at least until 1805, when she was in her mid-forties.18

Horatio, Lord Nelson, at the time he became acquainted with Emma Hamilton in 1798, had just won the Battle of the Nile, in which Napoleon’s fleet was turned aside from its mission in Egypt. By this time Lady Hamilton was the leading hostess of Naples, and she put on a celebration for Nelson befitting the crucial victory. He became, besides Emma Hamilton’s lover, the dearest friend of her husband, and the two of them concealed their affair so carefully that all three maintained an intimate friendship. For such performances to succeed, all of them had to believe in their parts at least to some degree, and it is clear that in this relationship (a variation on the one shared by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire and Elizabeth Foster) there was love on all sides. Despite this, London society, to which they had all returned soon before Sir William’s death, looked askance at Lady Hamilton, and the reputation she had so slowly built up in Naples began to deteriorate again.

Sir William Hamilton died in 1803, aged seventy-two, with Nelson at his bedside and Emma holding him; they mourned him with unfeigned grief. Nelson, however, was still a married man. Although he adored Horatia, the daughter born to Emma while Sir William still lived, there was little he could do for his beloved mistress beyond petitioning the government for a pension in return for her services to Britain. Their affair was ended abruptly by his death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, where his last thoughts were of Emma. In later years, Emma Hamilton, whose gift for theater had veered to the melodramatic, would faint away at theaters when the song “Rest, Warrior, Rest,” was played.19 Her own ending was more pitiful than melodramatic: although both Hamilton and Nelson had left her legacies, neither was adequate to keep up with her expenses, since she had learned how to spend like an aristocrat. She had gained, more or less, sexual respectability but had lost the frugal domestic touch she had learned with Charles Greville. Like Harriette Wilson, Emma Hamilton died in debt, attended by her daughter Horatia.

ACTRESSES

The Romantic period is the last in Britain for which a chapter on “improper women” might be the right place for actresses. Since the entrance of women on the professional stage in 1661, actresses had been seen as little more than high-class prostitutes. But during the Romantic era, the cult of the star came into being. The popularity of the theater helped to legitimize the profession. In these years, for the first time, actresses could be counted among respectable women–if they worked hard at it, and made no false steps into gentlemen’s beds. For some women–Mary Robinson, for example, or Dora Jordan, soon to be described–charm and glamour might be enough to secure the affection of audiences even if one had foregone one’s good name. But being an actress no longer in itself meant that one had done so.

Sarah Siddons (1755–1831)

________________________

Mrs. Siddons’s name, for theater fans, is still that of a star. Besides David Garrick, whose career ended just as hers was beginning, no actor came close to Sarah Siddons in fame or popularity on the stage at this time. Her career was built on her versatility in different tragic roles and the operatic intensity of her performances.

Siddons was born into an acting family: she was the sister of Charles and John Philip Kemble, and the aunt of Fanny Kemble, all renowned actors in their own right. This gave her an insider’s beginning, but her career was built on hard work. Actors trained for the London stage by working in the British provinces with touring theater troupes, and Siddons spent years touring. Her apprenticeship included a false start in London when, after what she thought was a successful season, she was dropped from the rolls of Drury Lane. She returned to the provinces, and by 1782 her performances were selling out regularly in Dublin and Edinburgh in the summers. She worked during the year at the theater in the fashionable spa-town of Bath. At this point she returned to London and found herself, as sometimes happens, suddenly famous after years of work.

Siddons maintained her popularity, in part, by keeping up her reputation as a wife and mother. At her last performance in Bath on the way to the big time of London, she brought her children on stage to show why she was leaving: there were few jobs for women in these years, but earning for the sake of one’s children always evoked pity and respect in an audience. And she had a reputation as a prude: it was said that she would not pronounce the word “lover” on stage, and her brother John Philip Kemble rewrote some of her parts for her to avoid sexual impropriety. Nor would she play Cleopatra, the only important tragic female role in Shakespeare that she refused, because the Egyptian queen’s sexuality was too brazen. Although she would play the parts of pitiable fallen women, Siddons “invested a dignity in each of these characters that transcended their sexual indiscretions.”20 She avoided playing the cross-dressing breeches roles that showed off legs and were indisputably sexy. In the many portraits of her, artists stressed her dignity as an artist or as a woman. She was careful about the company she kept, cultivating a middle-class and gentry circle of friends, including the novelist Frances Burney.

Mrs. Siddons

Known for the operatic intensity of her performances, Sarah Siddons maintained a reputation as a loving wife and mother as well as something of a prude. In the many portraits of her–such as this one of her in the role of Zara from Aaron Hill’s play of the same name–artists usually stressed her dignity, but her reputation for greed gave James Gillray the ammunition to portray her reaching for bags of money as she lets the symbols of the tragic actress–a dagger and a goblet of poison–fall to the ground. James Gillray, Melpomene [Mrs. Siddons], 1784; Mrs. Siddons in the Character of Zara, mezzotint by J. R. Smith, after Thomas Lawrence, 1783. PRINT COLLECTION

None of this was enough to save Siddons from one sort of attack, which may have arisen, indeed, out of her being so careful for her family’s welfare. She was reputed to be greedy–even to be uncharitable toward her fellow actors, at a time when acting was a much worse remunerated profession than it is now. There was little truth to these rumors, but they succeeded in stopping a few of her performances in the mid-1780s. It was true that Siddons was the primary breadwinner for her large family. It was also true that Richard Brinsley Sheridan, playwright, politician, manager of the Drury Lane Theatre (and grandfather to Caroline Norton), often neglected her pay, although she was not alone in finding her money late from Sheridan. However, satirists are not in the business of being magnanimous to their targets, and James Gillray portrayed Siddons in 1784 reaching for bags of money as she lets the symbols of the tragic actress–a dagger and a goblet of poison–fall to the ground (see opposite).

This was hardly the end of her career: Sarah Siddons continued performing regularly until 1812, several times acting as reader to the royal princesses, the elder daughters of George III, for the improvement of their taste and elocution. Unsurprisingly, Siddons was very far from being in debt when she died, and left an estate of over £50,000. She also left a permanently improved workplace for women in the acting profession and a new understanding that a woman could be an artist on the stage as well as something approaching a courtesan.

Dorothy Jordan(1761–1861)

________________________

Dorothy (Dora) Jordan had no such pretenses to virtue, but where Sarah Siddons was the primary tragedienne of her generation, Jordan was the most important comedienne, gaining a great deal of affection from her audiences by her performances of the breeches roles. Audiences knew her as “Little Pickles,” the name of one of her most popular parts, though she was also known more respectfully as Mrs. Jordan. Not least, she was known for close to twenty years as the mistress to William, Duke of Clarence, later King William IV.

Dora Jordan bore ten children to the Duke, all surnamed FitzClarence. Any relationship of such length and fertility is tantamount to a marriage, and both Jordan and the Duke were devoted to their children. Legal marriage, though, was not a possibility: the Duke could not marry a commoner, and Dora Jordan, herself illegitimate, was already the mother of two children out of wedlock. However, the stability and affection of the arrangement gave it a social legitimacy that may seem surprising; Princess Charlotte, for instance, went riding with one of the FitzClarence boys and wrote of Jordan to the Duke as “a true friend” and “a most affectionate mother.”21 James Gillray produced a caricature showing the Duke and Dora promenading to Bushy, their home (see page 83). While the Duke is red and puffs with exertion as he pulls his little monsters, Dora Jordan is poised and dignified, if somewhat inattentive as she learns her lines. In 1811, however, this placid situation came to an end. The royal family realized that they had a scarcity of legitimate offspring, and the Duke of Clarence broke off with Mrs. Jordan to marry.

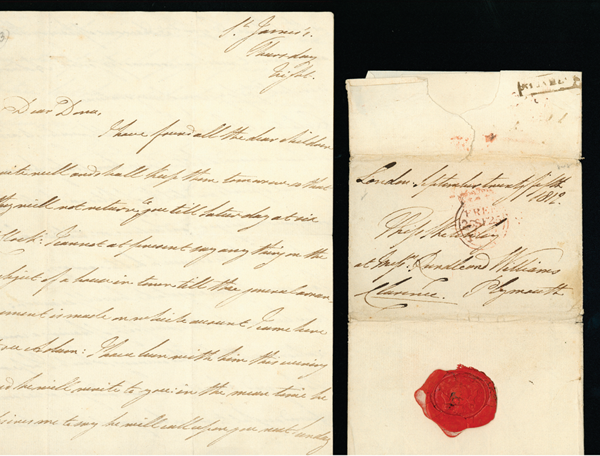

Mrs. Jordan

Dorothy–known as Dora–Jordan was the most important comedienne of her day, as well as the mistress for close to twenty years of William, Duke of Clarence. Her gamine appeal shines out from the portrait of her as Hypolita, one of the cross-dressing roles for which she was famous. Jordan bore ten children to the Duke, and James Gillray’s caricature satirizes the family on a stroll. After the Duke’s unwilling separation from Mrs. Jordan, he continued to take an interest in his family, as shown in this 1812 letter beginning “I have found all the dear children quite well.” Hypolita, engraving by John Jones, after John Hoppner, 1791. PRINT COLLECTION; James Gillray, La Promenade en Famille–A Sketch from Life, 1797. PRINT COLLECTION; autograph letter from William, Duke of Clarence to Dora Jordan, September 25, 1812. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

By then it was impossible to assault a woman generally acknowledged as one of the great performers of her generation and a dedicated mother. So when, in 1813, the Times of London published a scathing denunciation of Dorothy Jordan soon after urgent financial need forced her back on stage, it did not go unanswered. The attack claimed that she brought shame to the stage and double shame to the Duke, who could have “sent her back to penitence and obscurity” for daring to act in public once again. But the public was by no means in accord with the Times, always a stodgy newspaper and then under a particularly conservative editorship. The night after the piece was published, the audience at Jordan’s performance “shouted its applause … until the tears came to her eyes” when one of the characters recited the line “You have an honest face and need not be ashamed of showing it anywhere.”22 Jordan herself replied to the Times with a widely reprinted and admired defense–not of herself, but of the Duke of Clarence, against whom unfair charges had also been made. She did not deign to reply to the charges made against her personally. Mrs. Jordan had returned to the stage because of debt caused by her son-in-law’s fiscal mismanagement, rather than her own. She died in France, unexpectedly, three years later, her life an illustration of how talent and good nature can make inroads against even the most rigid social conventions.

FEMALE HUSBANDS AND ROMANTIC FRIENDS

Although there was no developed lesbian culture of the kind one finds now in many countries, lesbians in the Romantic period were not such “impossibilities” as Queen Victoria is reputed to have thought them.23 The evidence of lesbian life in the Romantic period shows us one final way women could make a name for themselves as improper women–but it also shows ladies who achieved adulation and fame simply for living as they wished to.

For women who loved other women, or just liked them a lot, the best evidence we have is from scurrilous and defamatory documents. Most of these start from the ancient assumption that sex without a penis simply isn’t sex. Logically, then, women who are attracted to other women are, in some sense, men manqués, who have to make up their deficiencies by artificial means. And indeed this is what we see in eighteenth-century Britain. Mary Hamilton is one of the best-known “female husbands”–women who dressed and passed as men, married other women, and used a dildo or some other device to have sex with their wives.

Exposed

For centuries, British songs had described young women dressing as sailor boys or soldier laddies to seek their sweethearts–as well as adventures that were otherwise impossible for girls. The ballads always included an amusing or moving scene of discovery, one of which is shown here in a French take on the tradition. In real life, women who cross-dressed, especially to seduce other women, were often tried for fraud. Lindor et Clara, II, engraving by F. Bonfoy, after Francis Wheatley, ca. 1785. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Chaste union?

An 1829 pamphlet offered a somewhat naive view of same-sex marriage, claiming that the “female husband,” James Allen, maintained the disguise of masculinity by entirely avoiding physical contact with his wife, Abigail, during twenty-one years of marriage (James’s physical gender was discovered only after death). These drawings of the couple are from An Authentic Narrative of the Extraordinary Career of James Allen, the Female Husband (London, 1829). PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

Denunciation and titillation

The Surprising Adventures of a Female Husband, describing the trial of Mary Hamilton–written by none other than the novelist Henry Fielding and first published in 1746–was reprinted in 1813, at the height of the British Romantic era. In this pamphlet, Fielding, in a humorously titillating style, denounces Mary Hamilton’s marriage to another woman as unnatural. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

A long European tradition of cross-dressing women existed, and reasons to pass as a man were as likely to be economic as sexual.24 In Britain, indisputably heterosexual women who disguised themselves as soldiers or sailors to follow their sweethearts into war were celebrated in ballads and prints. When female husbands were discovered, however, they were tried as frauds or vagrants. Mary Hamilton would not be remembered today except that the novelist Henry Fielding, also a judge in London, wrote a pamphlet telling her story using, apparently, “13% facts” (and by calculation, 87% fiction).25 Fielding’s original pamphlet came out in 1746, and denounces Mary Hamilton’s marriage to another woman as unnatural, although the situation is also meant to titillate the reader.

For our purposes, the most interesting aspect of Mary Hamilton’s case is that the pamphlet was reprinted at the height of the British Romantic era. The edition illustrated here dates from about 1813, with a frontispiece catering to the British taste for flogging. While the original Mary Hamilton was described as merely using a dildo to satisfy her wife, the 1813 Mary Hamilton has become a “traveling saleswoman of her specialized wares.”26 Despite its coarseness, the frontispiece is meant to amuse; lesbians here are naughty, perverse even, but they are still sexual beings.

The 1829 pamphlet An Authentic Narrative of the Extraordinary Career of James Allen, the Female Husband, by contrast, has lost its sense of humor. James and his wife, Abigail, look soberly at each other in the drawings reproduced here. The writer’s main point is to convince the reader that for twenty-one years James Allen kept up the pretense of masculinity by the total avoidance of contact with Abigail. Not only has the dildo disappeared but so has all physical affection. We should probably not interpret this to mean that British prudery blossomed between 1813 and 1829; rather, we should read these pamphlets together as evidence that sexuality in the nineteenth century was then, as it is now, the subject of a very wide range of opinions.

Becoming a female husband was not the only way for women to express love for each other in the Romantic era. Another possibility existed then that is now largely lost to us: romantic friendship, a tender coupling off that formed an alternative to marriage for a few women, and that was enjoyed in a less extreme form by many more. Lady Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831), the most famous pair of romantic friends, were in their heyday in 1813.

The Ladies of Llangollen,27 as they were known, came from old Irish families, with Eleanor Butler the older and more determined of the two. While still in Ireland they became friends and, finding their families immovably opposed to their desire to spend their lives together, eloped, taking a tour of romantic and mountainous Northern Wales. In 1780 they settled there in Llangollen, finding a little cottage, Plas Newydd, where they could spend their lives in retirement. This consisted primarily of quiet activities: reading, writing, studying, keeping accounts–as the ladies said, most of their pleasures had to do with paper. Many of the others took place in the sedulously tended gardens, planned according to the taste of the day for the picturesque and the gothic. There were shaded garden seats for reading, but the ladies were full of energy, and recorded in their journal running “round the garden in the freezing rain,” and coming in to enjoy the blazing fire afterward.28

The other great pleasure of their lives was home improvement, and over their many years together the ladies added to Plas Newydd constantly; it had become a small mansion with a farm by the time Eleanor Butler died in 1829. (Sarah Ponsonby, though sixteen years younger, followed her in 1831.) Because of this impulse to improve–it was a rage they shared with many others in rural Britain–the ladies were chronically in debt. However, although owing money sent many into debtors’ exile across the Channel, Ponsonby and Butler, unlike Harriette Wilson or Dora Jordan, did not die alone in France. In fact, they managed their money troubles adroitly in Wales. They were able to live, indeed, exactly as they had planned when they eloped, in loving and intimate friendship away from the world.

Romantic friends

The most famous example of a loving and intimate companionship is that of Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, an Irish couple who were in their heyday in 1813. Known as the Ladies of Llangollen, the charismatic pair attracted visitors such as William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, the writer Mme de Genlis, the scientist Sir Humphry Davy, the young Charles Darwin, and the Duke of Wellington. The Rt. Honble. Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Ponsonby, lithograph, after 1831. PFORZHEIMER COLLECTION

The world often came to visit them, however: William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, the writer Mme de Genlis, the scientist Sir Humphry Davy, a young Charles Darwin, and the Duke of Wellington, among many others, came to the cottage over the years. It became a tourist attraction, as visitors came to see the cottage and enjoy the placid life and devoted affection the ladies shared. Sarah Ponsonby, Eleanor Butler, and their way of life had a charisma that is gone now, the victim of a wider acceptance of lesbian ways of life.

Do we, then, know that they were lesbians? There is no direct evidence. If they had flaunted sexual passion for each other, they would quickly have been run out of Llangollen. When a newspaper report did insinuate that they were lesbians, the ladies were insulted and wounded. Yet the rumors persisted, as they do even now. Hester Thrale Piozzi, Samuel Johnson’s friend and patron, who moved to Northern Wales in her late middle age, was also a good friend of the ladies and yet described them as “damned Sapphists” in her diary. This has been rightly described as an “example of the doublethink that made it possible to be aware of lesbian possibilities, yet defend romantic friendship as the epitome of moral purity.”29 But what is being suppressed by this double consciousness? Perhaps it’s the same thing that was suppressed when gambling and adultery became unacceptable among women of the very highest classes: gaiety in the original use of the word. While there were no fewer ways for women to get into trouble in the Victorian period, they carried a heavier moral burden, as they pursued their pleasures with straight faces.