Chapter 15

THE SECRET MISSION

THE SECRETARY of war had instructed General Crook to install Standing Bear and his little band on government land. The Poncas wanted to go home to their land on the northern bank of the Niobrara, but technically that was part of the Great Sioux reservation. Following the Dundy determination, if Standing Bear or any of his twenty-five fellow relators were found on an Indian reservation, any Indian reservation, they could be arrested, removed, brought before a judge, and possibly imprisoned.

After carefully studying maps of Nebraska and Dakota Territory, Crook discovered another loophole through which he could slip Standing Bear. Several fertile islands that split the Niobrara River into five fast-flowing channels just before it hit the Missouri did not fall within the boundaries of the Sioux reservation when they were extended in error in 1868 to include Ponca lands. The surveyors had used the river as the southern boundary of the new Great Sioux reservation. The Poncas, however, considered these islands part of their ancestral homeland.

On May 19, General Crook loaded Standing Bear and his band into their wagons and had them escorted north to the largest of the islands. This lush green island was, in Tibbles’s words, “a safe distance outside the Omaha reservation boundaries.”187 It was also separated from the Sioux reservation by the river, which the general warned Standing Bear and his party not to cross. At least this way Standing Bear and his Poncas would be on home ground.

But Crook knew that Standing Bear’s Poncas longed to live and die north of the Niobrara, where their ancestors were buried and where their most productive cornfields lay. To make the hearts of the Poncas ache even more, Yankton Sioux had been encouraged by the government to settle on the Ponca land north of the Niobrara, to legitimize previous government errors. The determined general set his sights on the Poncas’ desire for complete repatriation to their homeland before he was done. A Wyoming newspaper reporter had written of Crook, after accompanying him on his 1876 campaigns against the Sioux and the Cheyenne, “He has a dogged, stubborn pertinacity. When he once takes hold he never lets go.”188 Regaining title to the Poncas’ Niobrara land now topped Crook’s agenda, and he worked behind the scenes with Henry Tibbles, John L. Webster, and the Omaha Ponca Relief Committee to see that objective achieved.

The white settlement of Niobrara was located just two miles from the island where Standing Bear and his followers set up their tents, and Tibbles says that as soon as they had arrived at the site of their new home Standing Bear put his entire band—men, women, and children—to work chopping wood, which they bartered with the townsfolk for provisions. They had to use sign language to complete the exchange because not a single member of the Ponca band spoke more than a few words of English. The people of Niobrara, who had spoken up on behalf of the Poncas in the past, welcomed the return of Standing Bear’s band and were pleased to help them.

The complex legal maneuvering involving the Poncas and their land went over Standing Bear’s head, but he understood that U.S. law had been made to work for him and his people. When he asked why the court decision did not apply to his Ponca kinfolk in the Indian Territory, why they could not also return to the Niobrara and be reunited with Standing Bear’s band, it was explained to him that it would require a separate application to the court, and a second successful judgment. Standing Bear reasoned that if the law could work for him, it must also be made to work for the rest of his people, so he urged Henry Tibbles to help the Poncas one more time.

Tibbles later claimed that he himself had set his sights higher. With the precedent established, he says, he failed to see why the Standing Bear case could not be “the first step in freeing all Indians everywhere from the selfish and arbitrary domination of the Indian Ring and of Washington officialdom.”189 But for the moment, with most of the Ponca tribe still stranded in the Indian Territory, the focus had to be on them.

Tibbles says that he, General Crook, and John Webster talked long and hard about what move to make next. If they went through the courts, Webster indicated, they would need to officially make clients of Chief White Eagle and the rest of the Ponca tribe in Indian Territory. With that in mind, when Tibbles was taking Standing Bear back to Fort Omaha, stopping off at Joe’s Village along the way, he had discussed with Bright Eyes and her father the possibility of the pair going down to Indian Territory to secure the rest of the Ponca tribe’s authority to act on their behalf before a judge. Father and daughter had agreed to make the journey, but certain obstacles had to be removed first.

The true purpose of the trip would be kept confidential, to prevent Indian Affairs officials from interfering with it; there was no way that Secretary Schurz would want the Indian Territory Poncas roped into this affair. Officially, the journey to the Arkansas River would be made on the excuse that Iron Eye and Bright Eyes were visiting Iron Eye’s brother, White Swan, and his family. The trip would be authorized in writing by General Crook and funded by the Omaha committee—the Omaha Ponca Committee as it had become known. Crook quickly agreed to his part, and the committee gave its full blessing to the mission and provided the necessary funds once Tibbles presented the plan to the members.

Tibbles took credit for coming up with the idea for this secret mission, but it may have originated with Bright Eyes, and Tibbles was trying to protect her. She had no qualms about going behind the backs of people in authority, as she demonstrated by going off her reservation to obtain her teaching certificate, by drafting the 1877 presidential telegram and press statement for the Ponca chiefs and bringing in Reverend Hamilton, by making the illegal dash to Columbus to see the bedraggled Poncas on their forced march, and, later, by going to General Crook to urge him to go to bat for Standing Bear against his own superiors.

When he wrote of Bright Eyes’s secret mission to Indian Territory, Henry Tibbles sang her praises, saying that she was the ideal envoy. After spending six “exceptional” years at the mission school, he wrote, Bright Eyes won high praise at the private school in New Jersey “for her brilliance, her willingness to work hard, and her pleasant, winning ways.”190 Bright Eyes had already exerted a powerful behind-the-scenes influence in the Standing Bear case, and now she and her father eagerly prepared to make the trip to Indian Territory. Apart from the covert motive for the journey, Tibbles says that Bright Eyes adored her uncle, White Swan, and she genuinely wanted to see her relatives who were languishing in the Indian Territory. Besides, it would give her the opportunity to celebrate her forthcoming birthday with her Ponca kin—she would turn twenty-five on May 26.

As no one knew what tactic the Interior Department would attempt next, every day was vital, so Iron Eye and Bright Eyes set off as soon as the Omaha committee gave the nod. They went south by train as far as they could into Kansas, then took to the road and walked into Indian Territory.

On May 20, when they reached the Ponca Agency, thirty-five miles south of Arkansas City, they were dismayed to find that the settlement there, at the junction of the Arkansas River and Salt Fork, was a shambles. It had scarcely any roads or paths, and the 550 Poncas confined to the reservation had been provided with six leaky shanty houses built by Indian Affairs. After more than two years, the majority of the tribe, who had been thrown out of fine log homes in the north, still lived in tents. Those tents were spread beside the Christian crosses and grave markers dotting a cemetery where many members of the tribe had been interred since arriving from the north. Here, under the new regime, the old “un-Christian” burial customs of the Ponca people had been terminated by Indian Affairs agent William Whiteman. Sorrowing members of the Ponca tribe would have lamented that many a departed Ponca was now wandering alone in the Spirit World.

There was no church building here, and no school. For the past two years the children who had attended school at the northern reservation had gone without schooling. Agent Whiteman was meanwhile living in a large two-story wooden frame house, the first genuine residence to be erected at the site, built by white laborers from Arkansas City at a cost of $2,500 and paid for with government money. Henry Tibbles wrote that when Bright Eyes returned to Nebraska, she remarked that the handsome agent’s residence “somehow looked strangely out of place among the tents and graves.”191

Fortunately for them, Bright Eyes and her father arrived at the settlement when the agent was away. Agent Whiteman frequently went to Arkansas City on business, staying overnight at the Central Avenue Hotel, and by chance the paths of the Omaha pair and the agent did not cross. As the visitors discovered, the agent was keeping the Indian Territory Poncas cut off from the outside world. After a tearful reunion with White Swan, his ailing wife, and their other Ponca relatives at the settlement, Iron Eye and Bright Eyes learned that the Poncas knew nothing of Standing Bear’s court victory. They didn’t even know that Standing Bear had taken the government to court. Agent Whiteman had prevented newspapers from reaching the tribe, and he intercepted and opened all letters going in and out of the reservation, destroying any that he considered inflammatory. Under William Whiteman, the Ponca reservation was nothing more than a prison camp.

The Poncas told their visitors that in the middle of April the agent had suddenly announced his intention to build sixty new houses for the tribe. The amazed Poncas had not been able to work out why, overnight, he should become so uncharacteristically benevolent. Bright Eyes and Iron Eye knew why—the announcement had come after Andrew Poppleton and John Webster had petitioned the district court for the writ of habeas corpus for the Ponca runaways. Fearing publicity and closer scrutiny of how the Poncas in Indian Territory were being treated, Washington had instructed Whiteman to make rapid improvements on the reservation.

Behind closed doors, Bright Eyes and Iron Eye told the astonished Poncas the details of the court case, and of how Standing Bear was now a person in the eyes of U.S. law, entitled to live where he chose. To Chief White Eagle they also disclosed the secret reason for their visit. Elated by the wonderful change of fortune experienced by Standing Bear and his band, and excited by the possibility that the rest of the tribe might also return home to the Niobrara, that same day, May 20, old White Eagle discreetly dictated a long letter to Bright Eyes, addressed to Henry Tibbles.

In the letter, Chief White Eagle asked Tibbles to pass a message to lawyers Poppleton and Webster: “We had thought there was none to take pity on us. I thank you in the name of my tribe for what you have done for Standing Bear, and I ask you to go still further in your kindness and help us regain our land and our rights. . . . I want to save the remainder of my people, and I look to you for help.”192

It seems that White Eagle then confided to Bright Eyes that Agent Whiteman was robbing the Ponca people at every opportunity. He would have told her how Whiteman purchased white man’s horses at top prices and then expected the Ponca farmers to use them to pull their plows. What the Poncas needed were Indian ponies, purchased from other tribes. Indian ponies cost nothing to keep. Unlike white man’s horses, Indian ponies did not need to be sheltered in stables or kept in corrals, and they did not have to be fed grain every day either. Over the winter, the Indians simply turned their horses loose, and they lived off cottonwood bark and came back next spring fit and healthy. White man’s horses were of no use to Indians; they were a waste of good money. They were more expensive to buy than Indian ponies and more expensive to keep. Yet Whiteman had persisted in paying big money for horses and feed to Arkansas City suppliers.

And then there were Whiteman’s other extravagances. White Eagle and his clan chiefs would have reeled off a string of instances where the agent had paid too much for goods for the reservation. They might have been In- dians, but they were not stupid. They heard things, they saw things. Sometimes Whiteman would withdraw a contract from one man in Arkansas City a week after it had been awarded and give it to friends like agency trader Joe Sherburne at a higher price. Apparently Bright Eyes took up her pen once again and had the chiefs dictate statements about the agent’s buying habits, and then had them sign these affidavits, which she witnessed.

That day or the next Whiteman returned to the agency to find Bright Eyes and her father staying with White Eagle. They had come from the north with official permission so there was nothing he could do about their presence, but he immediately realized that the pair had brought news of Standing Bear’s victory to his otherwise ignorant Poncas. He was far from happy about that and knew that Washington would be equally unhappy. Rather than shy away from the agent, Bright Eyes boldly went to see him. For heartfelt reasons, as well as to promote her cover story for the visit, she asked permission for her uncle and sick aunt to return to the Omaha reservation with Iron Eye and herself. True to form, Agent White-man refused her request point-blank.

The day after Bright Eyes and her father arrived at the settlement a new drama was set in motion by Standing Bear’s gigantic brother Big Snake. Excited and emboldened by the news of his brother’s court victory and unable to see why Judge Dundy’s ruling did not apply to the Poncas in the Indian Territory, Big Snake decided to test the Dundy decision. Perhaps Bright Eyes gave him the idea, but it’s more likely she urged him to be patient, to wait for the next court victory she was working to achieve. But Big Snake was impatient.

Another issue had been simmering in Big Snake’s breast, and it also had to do with his rights. Not long before, the government had sent eight Ponca children away to a new boarding school in a former army barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, set up exclusively for Indians. One of those children was Big Snake’s only son. Two of White Eagle’s children had also been sent there. At Carlisle, the children were forced to cut their long hair and wear school uniforms. According to the New York Observer they were “governed kindly but firmly.”193 Unlike white boarding school students, they weren’t allowed to go home over the summer but were hired out to white families around Carlisle as servants. Their lessons were taught exclusively in English, and they were permitted to write home just once a month, in English. Big Snake could not read English. He and his wife were pining for their boy. But more than that, Big Snake wanted to know what right the government had to take his son away from him.

Determined to prove he had rights too, just like Standing Bear, Big Snake gathered fellow members of the Soldier Lodge around him in a council. Together they discussed what they might do in light of his brother’s successful judgment, and an idea occurred to them. The Southern Cheyenne, who for the past four years had been sharing a reservation with the Arapaho one hundred miles to the southwest, had offered to sell the Poncas Indian ponies to help make up for their heavy stock losses. But Agent Whiteman, intent on buying horses through his friends, had refused to allow the Poncas to make the purchase from the Cheyenne. The plotters decided to use this to their advantage and to act immediately.

That day, May 21, Big Snake and thirty other Ponca men went to Agent Whiteman, informed him they were going to the Cheyenne reservation to buy horses, declared they didn’t need his permission to go, and then left the agency, knowing that Whiteman didn’t have the physical resources to stop them. Setting off immediately, they made their way along the Arkansas River toward the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation, leaving Agent Whiteman seething behind them.

Whiteman recognized this as a deliberate attempt by Big Snake to test the Standing Bear judgment and prove that all Indians were persons and could not be confined against their will on a reservation. Before he joined the Indian Affairs Bureau, Whiteman had been a small-town lawyer in Baxter Springs, Kansas, and was elected to a single term as Cherokee County attorney. Confident that Big Snake did not have a legal leg to stand on, he immediately sent a messenger to the telegraph office in Arkansas City.

A wire was sent to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington containing a report from Agent Whiteman that Big Snake and thirty “renegades” had left the Ponca reservation to go to the Cheyenne reservation without his permission. Whiteman requested that the Ponca party be arrested on reaching the Cheyenne reservation and detained at the nearest Indian Territory military post, Fort Reno, “until the tribe has recovered from the demoralizing effects of the decision recently made by the United States district court in Nebraska, in the case of Standing Bear.”194

This was the opposite of the truth, of course. Far from being demoralized, the Poncas had been uplifted by the Dundy decision. Whiteman wanted to keep the agitator Big Snake and his followers in the Fort Reno guardhouse, away from the rest of the tribe, for months if necessary, until all Poncas in the Indian Territory saw the folly of hoping to go home to the Niobrara and reuniting with Standing Bear’s band. Already several Ponca leaders, including Lone Chief and even Standing Buffalo, were inclined toward accepting their fate and making the best of things here in the Indian Territory. If Whiteman could separate the troublemakers from the others, he was sure the rest of the tribe would soon fall into line.

Interior Secretary Schurz immediately asked the secretary of war to act in the Big Snake matter. The next day, May 22, General Sherman telegraphed General Sheridan in Chicago: “The honorable Secretary of the Interior requests that the Poncas be arrested and held at Fort Reno, in the Indian Territory.”195 Unlike Agent Whiteman, who wanted to lock up Big Snake and his followers for a prolonged period, Secretary Schurz urged that once they were in custody, Big Snake and his companions be returned by the army to the Ponca reservation at the Arkansas River as quickly as possible, before friends of the Poncas in the North heard about their arrest and instigated legal action on their behalf. “You may order this to be done,” Sherman told Sheridan.196

To counter the claim that Big Snake could be expected to make—that the district court decision had given him the right to leave the Ponca reservation—General Sherman told General Sheridan in his telegram, “The release under writ of habeas corpus of the Poncas in Nebraska does not apply to any other than that specific case.”197

Sherman was essentially right, since Standing Bear and his party had been released on a technicality. Had General Crook’s orders required him to hand his prisoners over to the civil authorities and had General Crook complied, as he would have done, Standing Bear and his companions would have been taken before a judge, and that judge would have found that they were on the Omaha reservation illegally, and he could have been expected to order their return to the Ponca reservation in the Indian Territory.

Clearly the Interior Department and the War Department had closed ranks. Until challenged and tested in court, this was the stance they would take in all incidents involving Indians from this point on. As far as the government was concerned, Standing Bear’s was an isolated case, and no other Indian had rights under the Constitution. Of all the Indians in America, only Standing Bear and his twenty-five Ponca companions were persons in the eyes of the law, and that was the way Carl Schurz and his colleagues intended it should stay.

General Sheridan in turn passed Sherman’s order regarding Big Snake on to the military district commander at Fort Smith in Arkansas, which was both the military and judicial administrative center for Indian Territory. That officer passed the order to the commander at Fort Reno, a post four miles west of present-day El Reno in western Oklahoma that had the task of watching over the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation and the Ponca reservation. Big Snake and his party were duly arrested on the Cheyenne reservation and taken to Fort Reno. By the beginning of June, Big Snake and his companions had been delivered back to the Ponca reservation by the army.

Bright Eyes and Iron Eye were still at the reservation when Big Snake’s unhappy band was brought back under guard. They had no idea at the time that Big Snake’s return had been made possible by another illegal order. Astonishingly, through ineptitude, arrogance, or misplaced pride, the Interior Department had requested, and the War Department had once again issued, an order that contravened the law. As in the Standing Bear case, General Sherman had ordered that Big Snake and his party be arrested, detained at a military post, and then returned by the army to the reservation from which they were deemed to have escaped. As the Dundy determination had made pointedly clear, Big Snake and his party could be arrested for being on the Cheyenne reservation without permission, but the law required that the commander at Fort Reno be ordered by the War Department to immediately escort his prisoners to “the civil authority of the territory or judicial district” in which they had been found—in this case, the federal marshal at Fort Smith, Arkansas—and handed over. The prisoners would then be brought before a judge at Fort Smith. Ironically, the judge would no doubt order them returned to their reservation, but the law would have been followed, to the letter.

Why the German-born Schurz deliberately and stubbornly ignored the law a second time defies comprehension. He was apparently determined not to admit that he had been wrong in the Dundy case. To him, to order Big Snake handed over to civil authorities would acknowledge that the judge had been right in the Dundy ruling, and that Schurz had indeed requested an unlawful act in the Standing Bear case. It can only be concluded that Schurz had been so stung by the Dundy judgment and took it so personally that he lost his perspective, his objectivity, and his respect for the law.

Had this latest illegal act by the authorities become public knowledge there would have been uproar among the Poncas’ white supporters, and Henry Tibbles and his team would have been handed red-hot ammunition for their campaign. But Agent Whiteman acted quickly to ensure that didn’t happen. The soldiers who returned Big Snake and his party to the reservation stayed at the agency for the time being and, backed by their guns, Whiteman kept Bright Eyes and Iron Eye separated from Big Snake and ordered the pair to leave before they had time to ask difficult questions. Smuggling White Eagle’s letter and the affidavits about Whiteman’s financial dealings off the reservation with them, Bright Eyes and her father said their tearful farewells to White Swan, his wife, and the other Poncas at the Arkansas River reservation. As they walked up the road toward Kansas and the train back north, they left behind a promise that good people in Nebraska would help the stranded Poncas.

Once the troublesome Omaha chief and his intelligent daughter were out of sight, Agent Whiteman again sealed off the Poncas living at the Arkansas River from the outside world. With Big Snake unaware that he should have been taken before a judge rather than returned directly to the reservation, with Bright Eyes and Iron Eye neither knowing nor imagining that the government had again acted illegally, and with no one at Fort Reno possessing the courage or the conviction to speak out about this latest travesty of justice, the details of the illegal handling of Big Snake and his colleagues would not become public knowledge for eight months. And by that time it would be too late. Much too late.

Big Snake, normally so gentle and conciliatory, was changed by this episode. He was now possessed by a notion—was he not, like his brother, also a person? And now that the white man’s law had recognized his brother as a person, how could it be argued that Big Snake was not? Big Snake blamed Agent Whiteman for preventing him from exercising the right that he felt sure good white men would now accord him. Furious with Whiteman for having him brought back to the reservation like a runaway dog, he simmered with resentment, declaring that he would never again speak to the agent.

Whiteman was shaken by Big Snake’s continued defiance. And he would have worried that Big Snake’s Cheyenne reservation excursion might have jeopardized his job, just at a time when his agency was about to grow. For, without consulting the Poncas, Commissioner Hayt had decided to relocate another tribal group to the Ponca reservation in the Indian Territory—370 members of the fierce Nez Percé tribe from Idaho who tried to flee to Canada, fighting the U.S. Army all the way, before surrendering. As the Arkansas City Traveler commented, “With the addition of the Nez Percé trade will be increased considerably.”198 The editor knew that the Bureau of Indian Affairs would give Whiteman much more to spend in Arkansas City in support of the Nez Percé.

In early June, Whiteman invited his new friend Nathan Hughes, Arkansas City postmaster and newspaper editor, to pay him a visit on the Ponca reservation. When Whiteman regularly rode up from the Ponca Agency to the frontier town, he would invariably collect agency mail from Hughes and place advertisements with him to be run in the Wednesday Traveler seeking bids for the supply of stock, supplies, materials, and contractors for the Ponca reservation. While he was in town, Whiteman would jaw with the newspaper editor and complain about his Ponca charges.

Whiteman found a sympathetic ear in Hughes. The editor had no love for the Poncas, but he recognized their commercial worth to his town and was annoyed by attempts of their white allies in Nebraska to have them repatriated to their old reservation on the Niobrara. For their part, the Poncas did their best to befriend Hughes. Chief White Eagle even invited editor Hughes to watch the tribe’s annual Sun Dance with its Soldier Lodge initiation ceremony—the same initiation that Henry Tibbles and General Crook had secretly undergone with the Omahas several years earlier.

The Poncas had kept up the Sun Dance tradition each summer since being taken down to Indian Territory, despite the fact that the Indian Affairs Bureau had banned the Ponca and the Omaha summer buffalo hunts after 1876. Hughes subsequently wrote a detailed and critical account of the “barbarous” Sun Dance ceremony for his Traveler readers. After describing the slits cut in the chests of the Ponca initiates, he commented, “Our only regret” was that the Poncas did not also “cut their fool heads off” while they were about it.199

Clearly Whiteman invited Hughes to the agency in June hoping he would run a story in the Traveler that might dampen any rumors about a disturbance at the Ponca reservation in late May—the unauthorized departure and enforced return of Big Snake and his thirty companions. Hughes was only too happy to oblige. In an editorial about the Ponca tribe that appeared in the Wednesday, June 18 edition of the Traveler, Hughes, an unabashed Republican, wrote glowingly of the state of affairs at the agency, from the fine agent’s residence to four houses under construction, albeit for white agency employees, and one hundred acres of corn under cultivation.

Hughes also noted in his June 18 editorial, “We think that the restless spirit of the Poncas can be justly attributed to the influence of whites at their old reservation in the north. Certainly no tribe of Indians in the Territory has a more attractive agency, and no reservation a finer body of land.” Whiteman assured Hughes that the “restless spirit” among the Poncas would soon be a thing of the past and the members of the tribe would settle down to a contented life in their new Indian Territory home.

That same month, twenty-five Poncas led by Walks Over the Other, Whistler, and Woodpecker slipped off the Indian Territory reservation. Following the route taken by Standing Bear and his escapees earlier in the year and selling their horses along the way to pay for food, they avoided detection and made it all the way to the Santee Agency in the Dakota Territory before swinging west to join Standing Bear on the Niobrara. Once they had arrived home, no orders came out of Washington for their arrest.

While Bright Eyes and her father were in the Indian Territory, Tibbles put together the draft of a book, a hurried memoir of the groundbreaking Standing Bear court case, The Ponca Chiefs, An Indian’s Attempt to Appeal from the Tomahawk to the Courts. It was little more than a compilation of documents relating to the case loosely linked by Tibble’s brief narrative, but he hoped to find a publisher who would see a potential market in the many Americans who had followed the case in the press.

Meanwhile, in early June, Bright Eyes and Iron Eye returned to Nebraska after their Indian Territory mission. On the way back to their reservation the pair paused in Omaha to give Tibbles a report on the appalling conditions on the Indian Territory reservation, which he published in the Herald and presented to the Omaha committee. Most importantly, Bright Eyes handed White Eagles’s lengthy letter to an impatient Henry Tibbles, who was anxious to receive the authorization it contained. He read it with relief and a rejuvenated sense of purpose. “Those words at last gave us clear, written authority to act for the stranded Poncas.”200

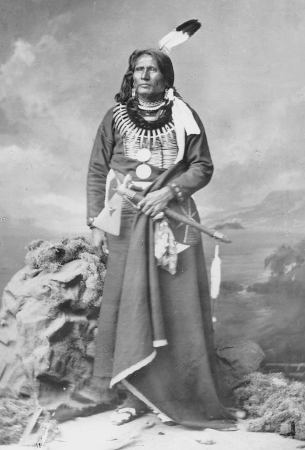

Standing Bear, in his formal attire, Washington, D.C., 1877, on his trip to meet with the Great Father, President Hayes. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

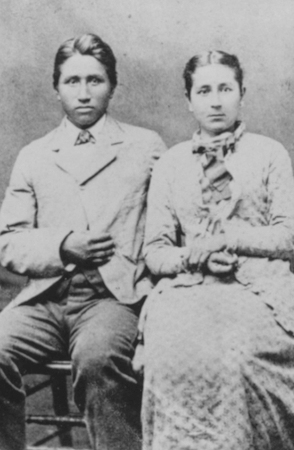

A confident Bright Eyes, age 25, circa 1880, “a lady of excellent attainments and bright intellect.”

(Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

The shy Bright Eyes, a.k.a. Susette La Flesche, with her equally shy younger brother Woodworker, a.k.a. Francis (Frank) La Flesche, at the beginning of the speaking tour of 1879–80. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

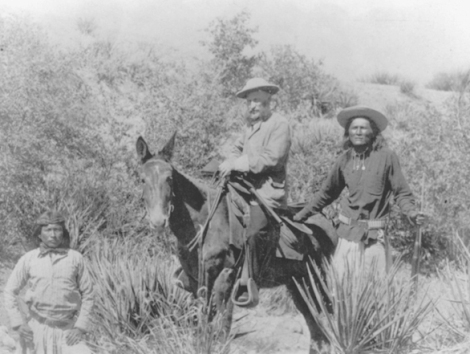

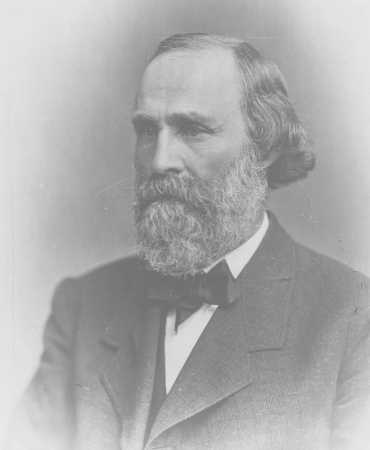

General George Crook, described by William Tecumseh Sherman as the greatest manager the U.S. Army ever had, and the greatest Indian fighter the U.S. Army ever had, here in full dress uniform. (Arizona Historical Society)

Shown below: General George Crook in his more typical garb, a civilian campaign outfit, on his mule, Apache. (Arizona Historical Society)

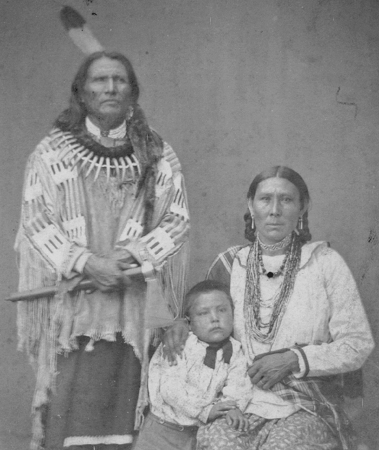

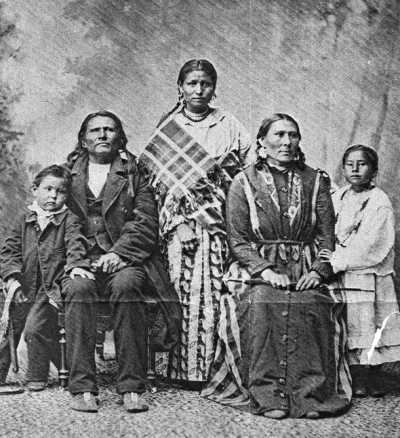

Shown above: Standing Bear and other Ponca chiefs, taken at I.S. Bonsall’s Photograph Gallery, Arkansas City, Kansas, February 20,1877, during their inspection visit to Indian Territory with Edward Kemble and James Lawrence. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

Standing Bear with wife, Susette, and their surviving daughter, Fanny, c. 1879, after the escape from Indian Territory. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

Shown above: After serving on the Union side of the Civil War, Thomas Henry Tibbles worked as a newspaper reporter and frontier guide, led a posse on the trail of outlaw Jesse James, and became a gun-toting Episcopal preacher. Shown here in his later years, Tibbles was assistant editor of the Omaha Daily Herald when he learned of the Ponca cause. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

Dr. George L. Miller, publisher of the Omaha Daily Herald and T. H. Tibbles’s boss in 1879. (Courtesy of the Omaha World-Herald)

Shown top left: A friend of Buffalo Bill Cody, District Court Judge Elmer S. Dundy loved hunting, fishing, literature, and justice. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

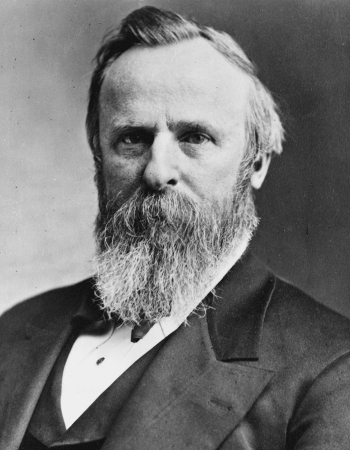

Shown top right: President Rutherford B. Hayes, 1877. (Library of Congress)

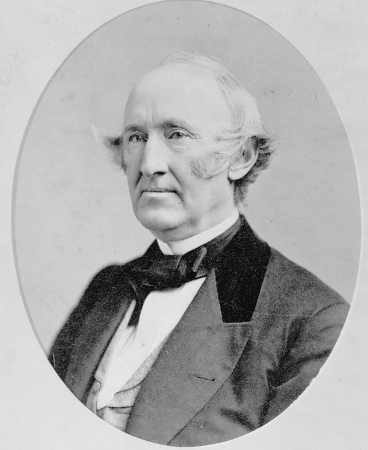

Shown bottom left: Andrew J. Poppleton, a passionate debater and one of Omaha’s first attorneys, was part of Standing Bear’s legal team. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

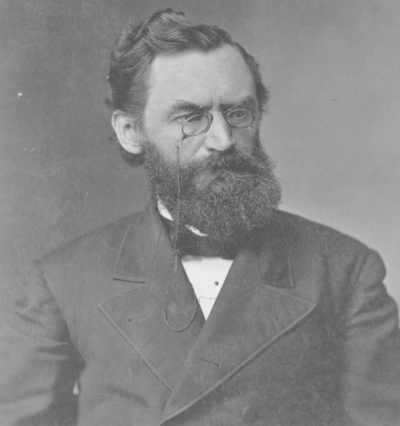

Shown bottom middle: John L. Webster, one of Standing Bear’s attorneys, devised the strategy around the Fourteenth Amendment and sought Poppleton’s help to convince a judge. (Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections)

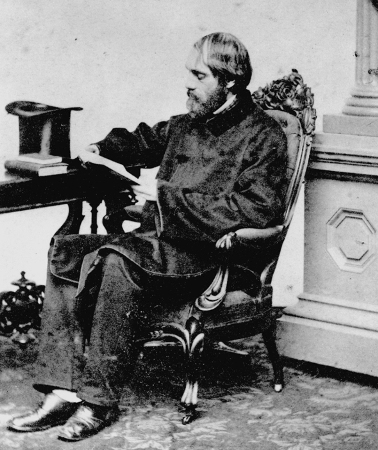

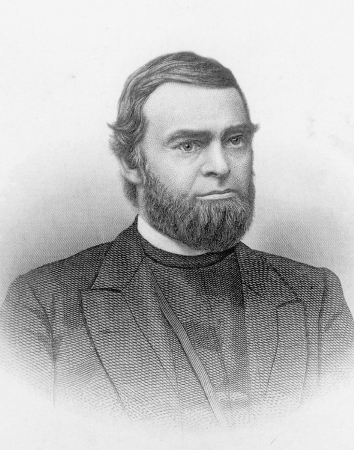

Shown bottom right: A brigadier general for the Union during the Civil War, Carl Schurz, as secretary of the Interior, pressed for the removal of the Ponca. (Library of Congress)

Wendell Phillips, the Boston orator who helped Henry Tibbles launch his Ponca publicity tour of 1879. Phillips also wrote a dedication in Tibbles’s book about the Standing Bear case, Ponca Chiefs. (Library of Congress)

Author Helen Hunt Jackson—H. H. as she was affectionately known to Standing Bear and Bright Eyes—joined the 1879 and 1880 tours in the East. (Library of Congress)

An advocate of a number of causes, Edward Everett Hale became a key member of the Boston Ponca Committee, later the Boston Indian Committee. (Courtesy of the Bostonian Society/Old State House)

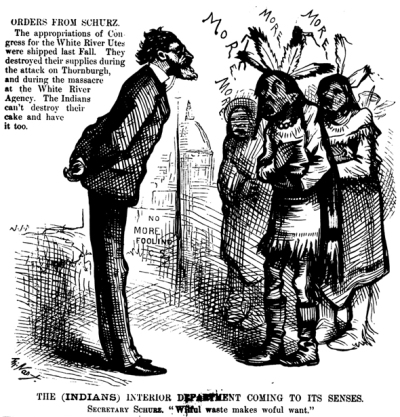

The 1880 Harper’s Weekly cartoon by Thomas Nast of Interior Secretary Carl Schurz, which so amused Standing Bear when he was in New York City. (Library of Congress)

The Right Reverend Robert H. Clarkson, Episcopal Bishop of Nebraska, founding member of the Omaha Ponca Relief Committee. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Samuel J. Kirkwood, who chaired the Senate select committee that considered the Ponca Commission’s findings and then presented his own 1881 Ponca bill to Congress. He became Interior Secretary after Carl Schurz. (Library of Congress)

Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, Ponca supporter, Schurz adversary, and sponsor of the well-meaning but ultimately disastrous General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act. (Library of Congress)

Shown below: Alice Cunningham Fletcher, allotting Indian land with Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé, 1889. (Idaho State Historical Society)

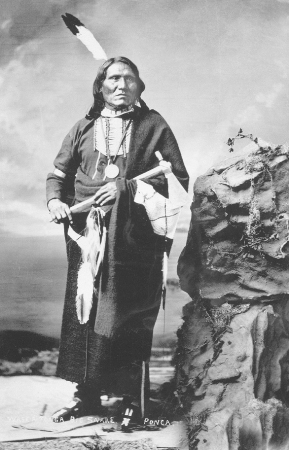

White Eagle, paramount chief of the Ponca tribe, who remained in the Indian Territory after Standing Bear’s escape, photographed in Washington, D.C., on the 1877 visit to meet the president. (Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library)

Bright Eyes, photographed in New York City in 1880 after she had become nationally famous, from a postcard that included her Inshta-theamba autograph issued by photographers Price and Campbell. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Big Snake, brother of Standing Bear, in Washington, D.C., 1877. Often described as a gentle giant, Big Snake was shot and killed at the Ponca Agency in Indian Territory on the orders of Agent William Whiteman. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

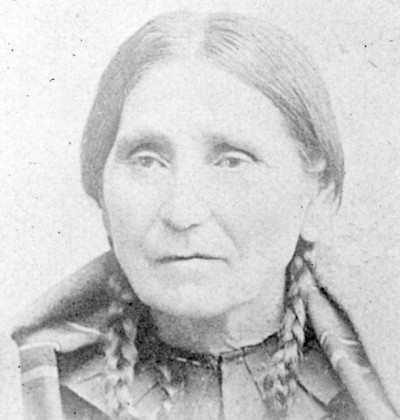

One Woman, a.k.a. Mary Gale La Flesche, Bright Eyes’s mother. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Standing Bear circa 1881. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Yellow Horse, the brother of Standing Bear, who escaped with him from the Indian Territory, photographed late in his life in 1906. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Standing Bear, his wife Susette, their surviving daughter Fanny, and their grandson and granddaughter, the children of Prairie Flower, late 1880s. (Special Collections, Tutt Library, Colorado College Library)

Shown below: Standing Bear with visitors at his farmhouse in the old homeland, Nebraska, late nineteenth century. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Standing Bear posing with his “peace” pipe for photographer A. E. Sheldon, at his farm, several years before his death. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

But just as it was poised to launch on the next phase, the Ponca campaign hit a snag. Shortly after Judge Dundy’s decision, Andrew Poppleton dropped out of the picture. Rather than offend Poppleton, who had helped win Standing Bear his freedom, Tibbles said nothing about how or why the esteemed lawyer withdrew from the crusading coalition. The precise reason is unclear, but in late May the Herald ran an article taking Poppleton to task over his interpretation of the historic 1857 Dred Scott case in his courtroom speech before Judge Dundy. The identity of the article’s author wasn’t revealed. If it was Tibbles, striving to display his thorough personal knowledge of the abolitionist fight, it certainly didn’t endear him to Poppleton.

On the other hand, perhaps Poppleton was pressured by his employer, the Union Pacific Railroad; he continued to serve as the railroad’s chief attorney for another nine years. Not that he deserted John Webster entirely. They would work together again, but for now he had other priorities, including a major property investment, a three-story brick office building under construction in downtown Omaha that opened the following year. The Poppleton Building still stands today.

For the moment, John Webster continued to be active in Standing Bear’s interests behind the scenes, but he was more reticent than before to take a Ponca case to court. Bright Eyes and Iron Eye may have brought back written authority from White Eagle for the lawyer to act on behalf of the entire tribe, but Webster felt that, unlike his Fourteenth Amendment defense in Standing Bear’s case, he did not have a legal hook to hang his hat on when it came to the rest of the tribe.

At the same time, word began to filter through from Washington that the opponents and exploiters of the Indians were mustering their forces, and one of their first targets would be the Omaha tribe, “as a reprisal for their help to the runaways,” according to Henry Tibbles.201 The word was that the bureaucrats and politicians were planning to legislate to remove the Omahas from their reservation and herd them down to Indian Territory, just as the Poncas had been dispossessed. To make things worse, Tibbles now discovered, after Webster read the fine print of the treaty the Omaha tribe had signed with the U.S. government in 1854, that it lacked a consent clause. Congress could relocate the tribe without its agreement.

There was yet another problem. Standing Bear and his band only occupied the island in the Niobrara where General Crook had settled them at the whim of the government. For them to have permanent legal tenure, it would be necessary for Washington to formalize their ownership of land on the Niobrara. And no one in Washington was putting up his hand to do that. It was time for the friends of Standing Bear to rethink their strategy before the Omahas were sent south by an unfriendly Congress, and before Standing Bear was thrown off the Niobrara tract by the politicians and made entirely homeless. Once those two pressing objectives had been achieved, the campaigners could think about safeguarding the rights of all Native Americans.

In mid-June, Tibbles, General Crook, and John Webster met with the members of the Omaha Ponca Committee to decide what to do next. Tibbles later wrote, “We could see a hard struggle stretching out ahead.” But “we cared not a rap whether our campaign would land heavily on the toes of the red tape Washington men, or those of the strong, ruthless Indian Ring, or those of the political bosses.”202

It was agreed that two things must be done for the campaign to succeed. First, a fighting fund had to be set up and substantial funds raised. Tibbles says that they were anxious “to raise several thousand dollars quickly” to combat the inexhaustible resources of their opponents.203 Some of this might pay for prominent but expensive lawyers further down the road; the remainder would contribute to other campaign expenses. Second, the campaign must not be confined to the West—it must be taken onto the doorsteps of their powerful opponents in the East.

With a strategy in place, initial campaign tactics were devised. While the committee organized fund-raising activities in Omaha, Henry Tibbles volunteered to stir up support in the eastern big city press. His plan was to use his credentials as a newspaperman to win the ear of editors and reporters, showing them a wad of press clippings and written endorsements from leading Nebraska figures to back up his story.

The mission to the East was expected to last at least three months. It seems that the owner of the Omaha Herald, Dr. Miller, wouldn’t give Tibbles a leave of absence—or perhaps the crusader didn’t seek it. Tibbles, who had set his mind on the Ponca campaign, resigned his position with the paper. The Ponca committee would cover his transportation, accommodation, and food costs while he was in the East, but he would not be paid a salary. Whether Tibbles discussed any of this with his wife, Amelia, before he handed in his resignation is debatable. He later wrote that Amelia was fully supportive of this eastern enterprise and encouraged him to keep going when the going got tough. But she must have been shocked to learn that her husband was going to leave his little family for months at a time, with no support. Amelia would have to make do with their meager savings and charity from local church people.

Omaha journalists gave Tibbles a send-off party, at which they praised his morals, his determination, and his courage, and expressed their admiration for him. He later wrote that he found the greatest inspiration of all from them. “These men who knew my faults and failings as completely as my virtues had wished me God-speed in a worthy cause of which they understood every detail—and the memory of their words helped me through many hard moments.”204

In late June, Henry Tibbles bade farewell to Standing Bear on the Niobrara and Bright Eyes and his other friends at the Omaha reservation, to his co-conspirators General Crook and John Webster, to the members of the Ponca committee in Omaha, and to Amelia and their girls, May and Eda, and then set off east. Conscious of the problems of credentials and credibility he had encountered during his wheat farmer relief appeal in the East five years earlier, this time Tibbles went armed with printed personal endorsements from General Crook, Bishop Clarkson, and leading Nebraska clergy.

Not content with these first-class references, Tibbles had gone down to Lincoln prior to his departure to see Albinus Nance, the new governor. Nance was a staunch Republican, a man who could have been expected to side with his Republican colleagues in Washington in the Ponca affair. But Nance was conscious of his local constituency and had one eye on his reelection chances in three and a half years. He knew that the state’s influential Protestant church leaders were behind the Ponca campaign. As it turned out, Nance would be reelected. And Henry Tibbles went east that summer of 1879 carrying a ringing personal endorsement from the governor of Nebraska.