introduction

A Rough Draft Of History, One Cover at a Time

The time cover is the most important real estate in journalism. The iconic red border grabs you by the lapels and says, “Pay attention.” That border divides the world into everything outside it and everything inside; everything inside is important, meaningful, urgent—and everything outside, well, not so much. The red border is a visual drum roll that has the effect of heightening everything inside it so that the image and the line get enhanced power and relevance and focus. It started as a visual flourish and ended up as one of the most recognizable signatures in the world. Each week, the TIME cover fuses word, art and design to become a part of history.

The red border didn’t exist when TIME was born in 1923. For the first four years of our history, there was just an elegant filigree to the left and right of the black-and-white charcoal portraits of the magazine’s cover subjects. But the magazine was languishing on the newsstand. In 1930, according to The Man Time Forgot, Isaiah Wilner’s biography of Briton Hadden, who founded the magazine with Henry Luce, TIME’s advertising chiefs went to newsdealers for advice, and one of them said, “What you need on the cover is pretty girls, babies or red and yellow.” The girls and babies just didn’t fill the bill, and yellow seemed too garish. One day, sitting in Hadden’s office, a friend of his named Philip Kobbe took a red crayon and drew a border around the cover of the current issue. Everyone loved it.

The red border debuted on the first issue of 1927, gracing a portrait of Leopold C. Amery, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies. Few remember Amery, but the red border stuck. In fact, the business side soon upgraded the paper stock so it would better accept color, and the cost was soon recouped by the additional revenue earned from selling color ads on the inside and back covers.

Through much of our history, the cover image was almost always a portrait of an individual. “Names make news,” Luce said, and his conception of TIME was that we would write about the news through the people who made it. This seems pretty unexceptional today, but in the 1920s and ’30s, it was a new and revolutionary notion. For Luce, history didn’t make the man; the man—and woman—made history.

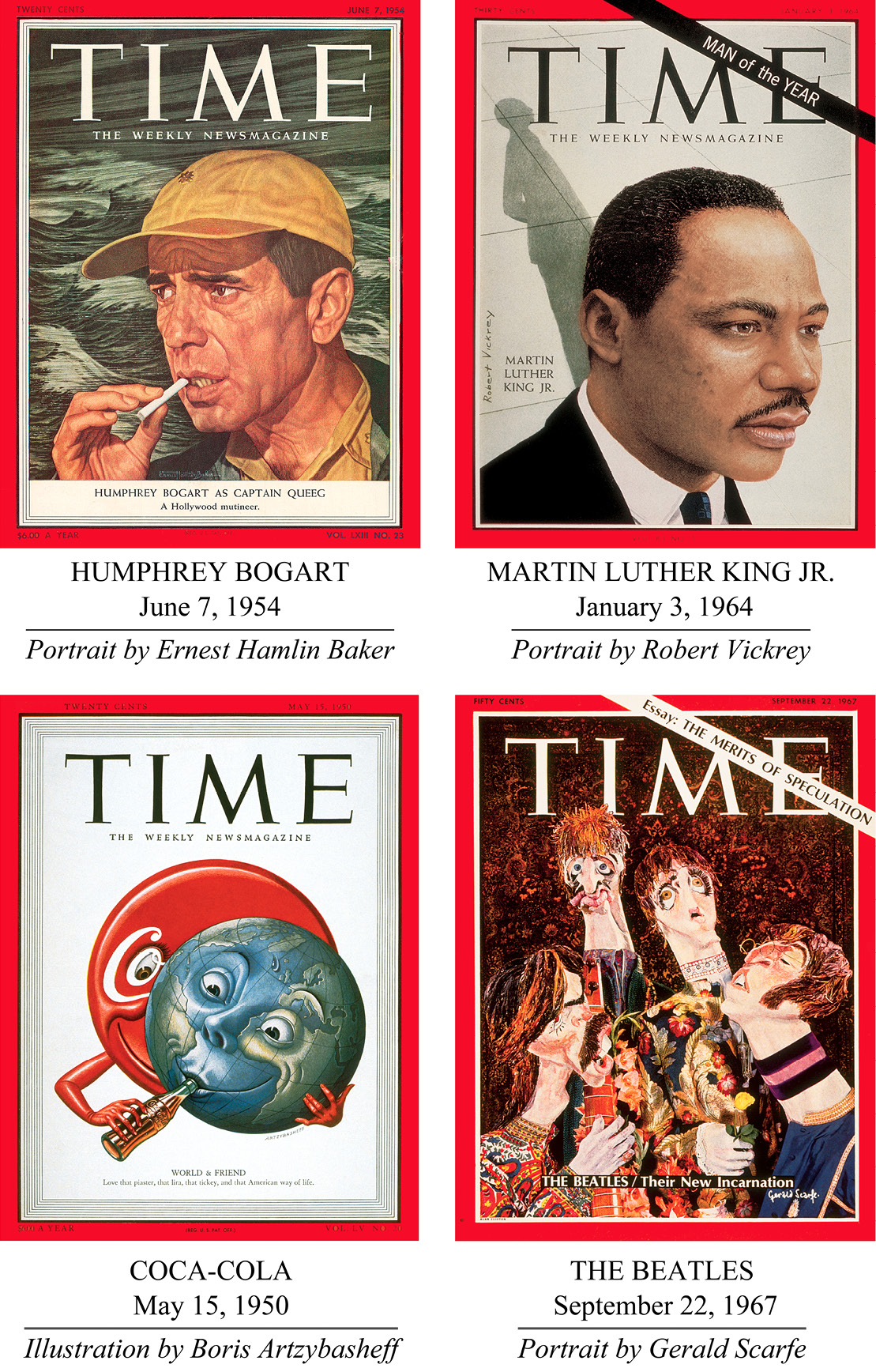

The first full-color portrait, an oil painting of Walter P. Chrysler, appeared in January 1929. Within 10 years, there were color photographs on the cover. But by 1939, TIME began to take a different direction. For the next 25 years, TIME featured distinctive painted cover portraits by three artists: Boris Artzybasheff, Ernest Hamlin Baker and Boris Chaliapin—the ABCs as they were known in the office. This era was the golden age of the TIME cover.

Baker was a Colgate university grad who started drawing caricatures when he was in college. Both of the Borises were Russians who had been displaced by the Russian Revolution. Artzybasheff escaped as a deckhand on a steamer and jumped ship in New York. Chaliapin was the son of the one of Russia’s greatest opera singers. In terms of style, Baker was the most straightforward and realistic, yet his covers often had a sweetness and optimism about them. Chaliapin’s pictures were moody, more impressionistic and often lyrical. Artzybasheff’s portraiture was extremely realistic, but his images, especially the backgrounds, were often surreal, displaying an imagination that was wild and surprising. From 1939, when Baker did his first cover, until 1970, when Chaliapin executed the last of his, the three men painted more than 900 covers.

Within a few years, these portraits added another feature. Because some of the subjects were not well known to readers, the artists started painting elaborate backgrounds filled with objects and iconography that put the person in context. One of the first of these was a 1941 portrait of the dissident Lutheran pastor Martin Niemoller of Germany; his face was flanked by a swastika and a cross. The backgrounds came to be symbolic landscapes with images and objects that helped identify the subject. They were as rich in their own way as the portraits. For many readers, the background came to be a kind of weekly puzzle helping them decipher the main image.

I have two portraits from this period hanging in my office. One is Baker’s wonderful rendering of Jackie Robinson, showing the beaming Brooklyn Dodger surrounded by giant baseballs. It is a happy image, with a sunny Robinson radiating optimism and confidence. It’s hard not to smile while looking at it. The other is Artzybasheff’s brilliant portrait of designer Buckminster Fuller with a head shaped like his greatest invention, the geodesic dome. It is so clever, so brilliantly executed and so much fun. It is irresistible.

By 1940 the filigree was gone. In the 1950s the logo began to be superimposed on the cover image rather than sitting above it. This created more of a pure poster effect. I’ve always conceived of the TIME cover as a poster, something that catches your eye and informs at the same time. Like posters, it is meant to be bold, clean, immediately understandable. To use Horace’s definition of great art: the TIME cover is dulce et utile—it teaches while delighting.

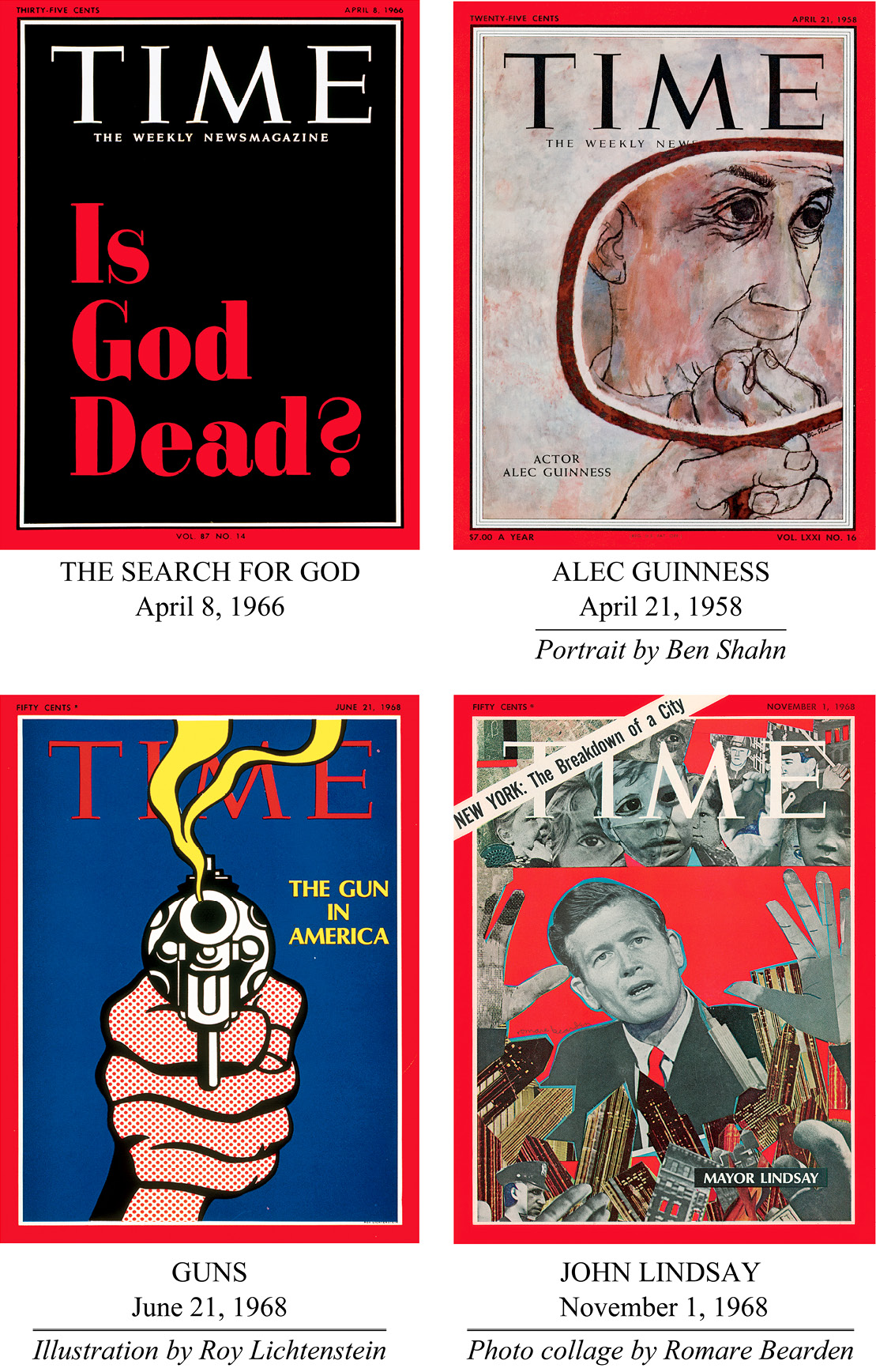

In the mid-’60s, TIME’s editors began moving the covers away from portraiture. They did not abandon it altogether but used more graphic images and bigger headlines to tackle social and societal issues. The iconic 1966 cover “Is God Dead?”—which simply used bold red type on a black background—was powerful, visually arresting and modern. One of my favorite covers from this period is Roy Lichtenstein’s 1968 “The Gun in America,” published a week after the assassination of Robert Kennedy. Just four issues before, Lichtenstein’s brilliant portrait of Kennedy, in the middle of his campaign for President, depicting him as a comic-book superhero, had been the cover of the magazine.

The red border remained unchanged until the late 1970s, when the magazine introduced a corner “flap”—a graphic version of a page corner being turned down. The idea was to feature a second big story. We also introduced a more compact logo that, like so many things of the ’70s, seems a little less than lofty today. Elegance should be a virtue of the TIME cover, and the classic logo, as well as the one today, preserves that.

The first time we changed the color of the border was for the edition we rushed to press in the wake of Sept. 11, 2001—an issue dominated by a single article and pictures telling the story of the terrorist attacks on U.S. The border was black. It was an echo of the time Life magazine changed its iconic red title box from red to black for its cover on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. We’ve since altered it three more times: a green border to commemorate Earth Day, a silver border for the 10th anniversary of 9/11 and a silver border for Barack Obama’s second Person of the Year cover, in 2012.

On occasion, we’ve created three-dimensional objects for the cover, like George Segal’s sculpture for Machine of the Year in 1983 and Christo’s globe for Planet of the Year in 1988. While these are genuine works of art, they work less well on a magazine cover, which struggles to capture three dimensions on a flat surface.

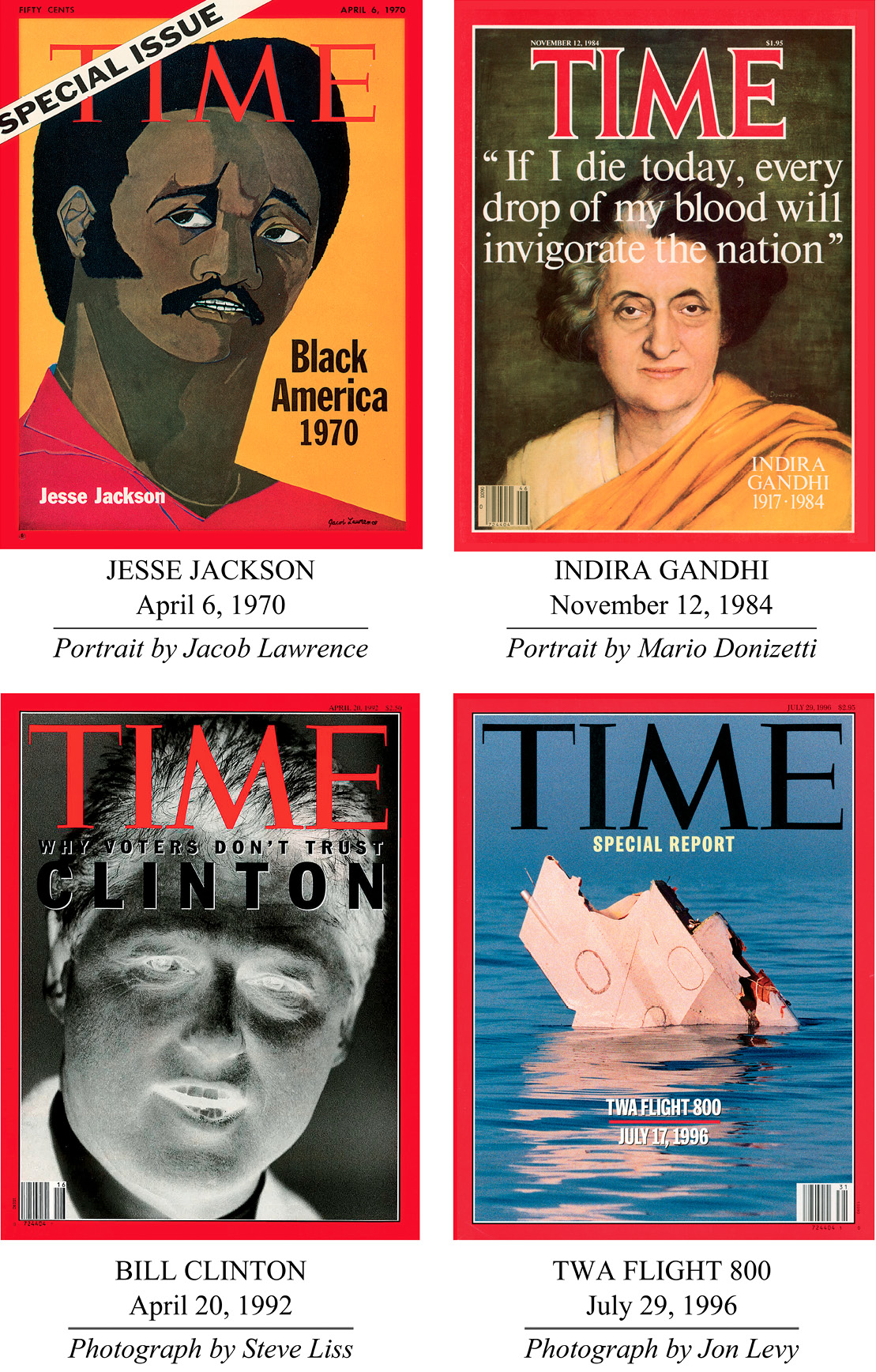

When I arrived at TIME in the early 1980s and began work as a staff writer, I’d see the cover for the first time on Monday mornings like our millions of readers. Sometimes I was pleased, sometimes disappointed, but it seemed like a mysterious and almost magical process that I could never be part of. A few years later, I was sometimes called on to participate in what became a tradition: a gathering of writers and editors and art and photo editors in a conference room on Friday night to look at cover options that were created by the art director. This process had its pluses and minuses. The virtues of it were that you got people’s first reactions and could get a sense of what was working and what was not. It also made more people feel included in the cover decisionmaking process. The downside was that it could be pretty arbitrary as well as demoralizing for the art director, and the opinions were just that, opinions.

When I became managing editor, I slowly began to change the process. I’ve always cared a great deal about design, and I have a fairly well-defined aesthetic. I wanted covers to be not a visual compromise but a bold, singular vision that would cut through the hurly-burly of the newsstand. I spend more time thinking about and working on the cover each week than any other part of my job. The cover was the single most important decision I would have to make for every issue, and I wanted the process to reflect that. We didn’t have the resources we once had to work on two or three cover stories a week, so the burden was that we had to choose both a story and an image to focus on. I’d work with our art director—first Arthur Hochstein, later D.W. Pine—to come up with a handful of images, often by several artists or photographers, that would make a striking and arresting image. We’d refine that over the course of the week, getting to the point that there was often only one option. With the arrival in 2009 of Kira Pollack as director of photography, we were even more proactive in planning and scheduling photo shoots not only for cover portraits but also images like the dueling wife and husband (with babe in arms) for “The Chore Wars” in 2011, the unweaned 3-year-old boy for our attachment-parenting story in 2012 and the child in a corner with a bullhorn for “The Power of Shyness,” also in 2012.

Under Hochstein, we came up with some memorable images: the ten-gallon hat over a pair of cowboy boots for “The End of Cowboy Diplomacy” in 2006 and, the same year, the Weegee photograph of the backside of an elephant for a Republican Party scandal involving underage congressional interns. Because I think a magazine should look both recognizable and fresh, we became known for doing striking images and graphics on a white background. Under Pine, who succeeded Hochstein in 2010, we’ve moved to a different style, with symbolic images that can hold big, bold and graphic type. The image supports a big line—New Jersey Governor Chris Christie with “The Boss” boldly superimposed, for example, or a man in a bow tie looking through binoculars with a backdrop of cumulus clouds for “Rethinking Heaven.”

Ultimately, it is the words that are the sell. I love it when the type forms either a triangle or an inverted triangle and seems to be a solid graphic image all by itself. We’ve continued to use great artists. In June 2013, the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei designed what may be one of the most beautiful covers ever, “How China Sees the World,” a dazzling red and white Chinese paper cutting that takes up every square centimeter of the cover real estate.

Under Pollack, we have done many memorable cover shoots, including Nadav Kander’s dreamlike portrait of Obama for the 2012 Person of the Year; Martin Schoeller’s photograph of Mark Zuckerberg, our 2010 Person of the Year; and an image of Steve Jobs by Marco Grob for the cover that marked the introduction of Apple’s iPad to the world.

Of all the cover decisions I’ve made, the one I lost the most sleep over was the graphic, haunting portrait by Jodi Bieber of a young Afghan girl whose nose was sliced off by the Taliban. It was one of those images that you could both not look at and not look away from. It was so strong that I could barely examine it myself, but I thought the grim reality was something that millions of people should see.

In this book, we have assembled a small selection of the more than 4,500 covers published by TIME over the past nine decades to tell the history of the period. Along with the covers are excerpts from their accompanying stories. Until 1982, bylines were a rarity and TIME spoke as a single entity, despite the fact that many prominent writers worked for the magazine. Where records exist, we have now lifted the veil of anonymity to reveal the contributions of writers like John McPhee, James Agee and John Hersey, among the many who gave voice to TIME.

Over 90 years, the cover has captured Presidents and Popes, heroes and villains, science and medicine, ideas and trends, scandal and catastrophe. The cover itself has become a touchstone in our culture. I get many letters every week telling me the cover subject is either worthy or not worthy of putting inside that red border. We try to live up to that iconic red frame. Every week, the goal is to create a cover that is both timely and timeless.