The Presidents

Though in office just over 1,000 days, Kennedy inspired a nation with his exuberance—and the power of the new medium of television

Photograph by Gerald French

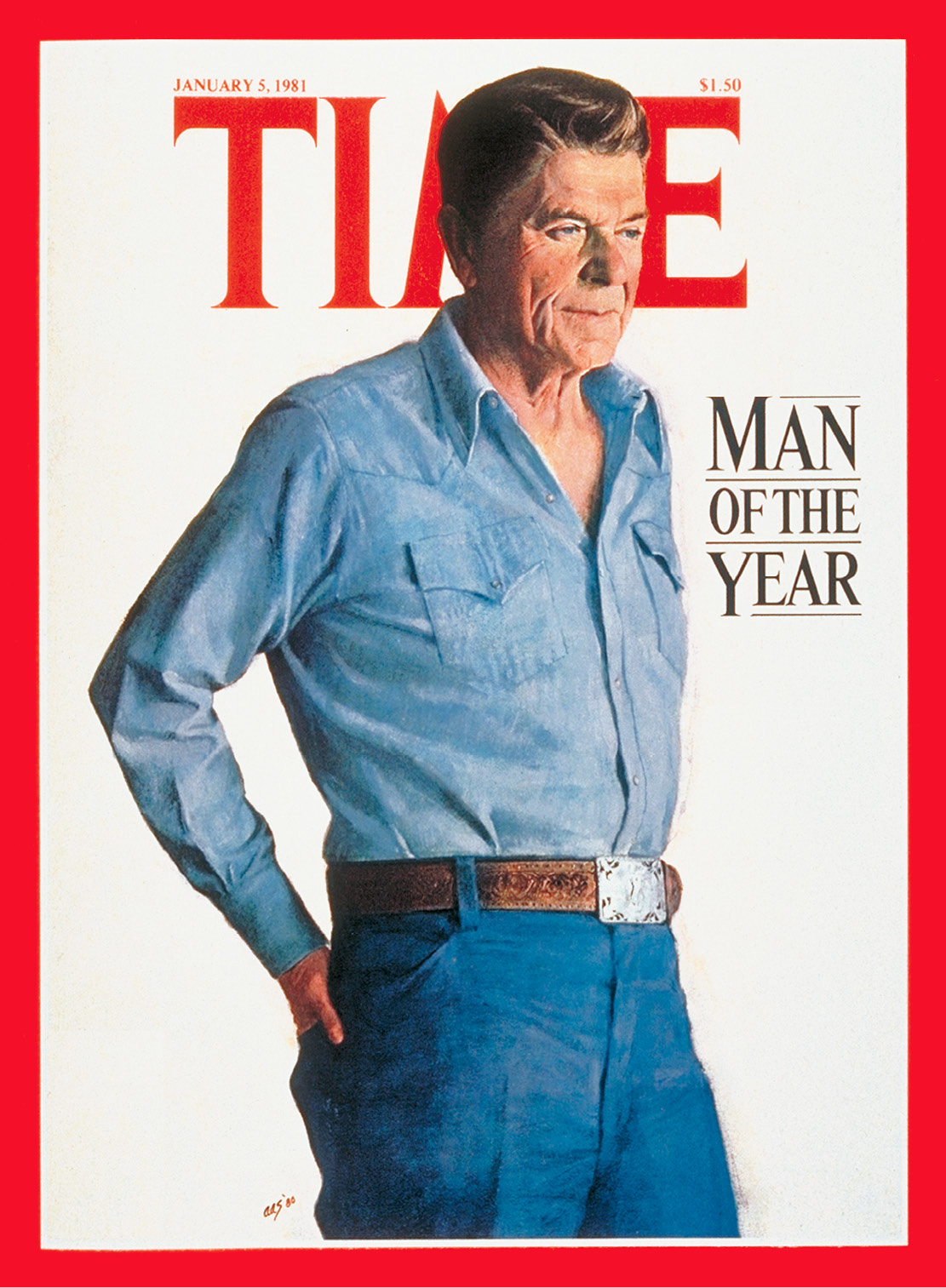

ronald reagan

january 5, 1981 | Portrait by Aaron Shikler

Always the gentleman, president warren harding came to office in 1921 with modest ambitions and a mild vision for his office. “If I felt that there is to be sole responsibility in the Executive for the America of tomorrow, I should shrink from the burden,” he said at his Inauguration. True to his words, Harding’s time in office was marked by the minor role he played. “To be a ‘good fellow,’ handshaker and amiable ‘regular guy’ and still occupy the President’s chair is, in the national mind, the realization of the highest American idealism,” time reported then.

In the 90 years since, the constitutional role for the President has not changed on paper. As Harry Truman said, “The presidency is exactly as powerful as it was under George Washington.” But the means and exercise of that power have swung like a great pendulum through times of war and peace, domestic strife and economic prosperity. Just a decade after Harding’s death in office, Franklin Roosevelt remade the presidency in ways that would have shocked many of the Founding Fathers. With the support of Congress, he claimed and wielded new powers over the banks, new controls over agricultural production and the power to create the social safety net that anchored the New Deal.

By the time of John Kennedy, those powers had grown even further: he had the clear ability to rally the American public through the new medium of television, and he was willing to use the Internal Revenue Service to target political groups that opposed him. This swing toward the empowered and unaccountable Executive reached its farthest point with Richard Nixon, who not only gained power from Congress to impose price controls and decoupled the dollar from the gold standard but also wielded the police and spying power of the presidency outside the control of the law to counter his political enemies. As a result of the latter and the Watergate break-in, Congress and the Judicial Branch reasserted themselves in a true test for the country. Swearing in Gerald Ford after Nixon’s resignation, Chief Justice Warren Burger grabbed the hand of Senator Hugh Scott, a Pennsylvania Republican, to celebrate the success of the American system. “Hugh,” said Burger, standing in the White House, “it worked. Thank God, it worked.”

The debate over presidential powers continued into the next century, as the country was tested by another attack, on Sept. 11, 2001. In its wake, Congress gave the President broad new powers to combat terrorism, and George W. Bush seized upon them in ways that are still debated. At one point, in 2004, his FBI director and his Attorney General threatened to resign with other senior Justice Department officials over a classified surveillance program that they had determined was in violation of the law. Faced with the threat, Bush agreed to alter the program, but the debate over the scope and secrecy of government surveillance powers did not go away. Barack Obama, who won office opposing much of Bush’s approach to the war on terrorism, found himself after his re-election facing outrage among his supporters for secret surveillance policies leaked by a young intelligence contractor.

Throughout this time, the power of the presidency did not reside solely in the actions Presidents took by order or veto. With the dawn of the era of mass communications and transcontinental flight, they found themselves occupying a much more public position, expected to respond to every major event and to travel the world to defend and promote the American project. In 1928, senior aides to Calvin Coolidge complained to TIME of the radio host Will Rogers’ mimicking the President’s voice to sell Dodge automobiles. Franklin Roosevelt used fireside chats to talk directly to the American people for more than a decade. Television helped bring in the age of Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan, a veteran of the big screen, became a master of the medium. Then, decades later, the Internet helped organize millions of Americans around Obama’s two elections. With each technological innovation, the White House’s ability to set the national conversation only increased.

Franklin Roosevelt was the first President to fly on a plane while in office, and in short order, globetrotting became a key part of the job description. Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, which created the U.S. Air Force, on board a plane. By 1959, Dwight Eisenhower was being hailed as a truly world leader, having been received by throngs in Ankara, Karachi, Kabul, New Delhi, Tehran, Athens, Madrid and Casablanca on one of his voyages. “I saw at close hand the faces of millions,” he reported on his return. The expectations proved a great burden to Kennedy. Reporters for TIME once found him in shorts, hugging his legs high over the Atlantic Ocean, suffering from the acute back pain that afflicted him, particularly on long trips. Today, frequent tours abroad are no longer remarkable, and Obama has used them to launch global campaigns.

But for all that, the politics of the office remain largely unchanged. Eisenhower called himself a “born optimist,” much like nearly every President before and since. “I was not brought up to run from a fight,” announced Truman, who also said he would “tell the people the facts”—phrases neatly paraphrased by Bill Clinton and a half-dozen others. They were men who invariably described themselves as defenders of freedom and free enterprise and of the better days ahead. In their view, as Reagan put, it is always “morning in America.” And in their care, the American experiment has survived to continue to test that promise.

Warren Harding

March 10, 1923

Portrait by William Oberhardt

After two years in office, Harding saw corruption scandals threatening to overwhelm his achievements. Five months after this issue came out, he would be dead.

He is not a superman like [Theodore] Roosevelt or [Woodrow] Wilson; he never pretended to be, and he should not be judged according to such lofty standards. He is important and successful as the embodiment of the American idea of humility exalted by homely virtues into the highest eminence. He is the actuality of the schoolboy notion that anybody has a chance to be President. Mr. Harding has no personal enemies. Almost everybody in Washington likes him and admits he is a “good fellow.” And to be a “good fellow,” handshaker and amiable “regular guy” and still occupy the President’s chair is, in the national mind, the realization of the highest American idealism. No one realizes this more completely and shrewdly than Harding.

Calvin Coolidge

January 16, 1928

Portrait by S.J. Woolf

Enjoying the fruits of an economic boom, he was able to restore public confidence in the White House after the Harding scandals. But then there was radio ...

Time was when court jesters got their ears stoutly boxed for following up a timely prank with an impertinence. Last week, though the technique had changed, the intent was the same when “those close to the President” pronounced Funnyman Will Rogers in bad taste. Having just served his country by amusing President [Plutarco Elías] Calles of Mexico at Ambassador [Dwight] Morrow’s behest, Funnyman Rogers, home again in California, performed in a nationwide radio program to advertise Dodge automobiles. During his piece, Funnyman Rogers announced that the broadcasting would switch to Washington, where President Coolidge “would say a few words.” The “few words” that followed were typically Rogersian but the voice that spoke them so closely aped President Coolidge’s voice that many a dull-witted radio owner switched off his instrument under the impression that he had heard the President actually endorse Dodge automobiles.

Herbert Hoover

March 26, 1928

Portrait by S.J. Woolf

Profiled during his first campaign, Hoover would be elected on his reputation as a public servant. But the economic collapse led to his defeat for re-election in 1932.

The central fact militating against Candidate Hoover is that many people cannot understand what he stands for. He is no forthright protagonist of an ideal or program. He puts forth no clear-cut political or social theory except a quiet “individualism,” which leaves most individuals groping. Material wellbeing, comfort, order, efficiency in government and economy—these he stands for, but they are conditions, not ends. A technologist, he does not discuss ultimate purposes. In a society of temperate, industrious, unspeculative beavers, such a beaver-man would make an ideal King-beaver. But humans are different. People want Herbert Hoover to tell where, with his extraordinary abilities, he would lead them. He needs, it would seem, to undergo a spiritual crisis before he will satisfy as a popular leader. Until then, his detachment, his impatience with questions not concrete, his zeal for his own job, will continue to be interpreted by many as political cowardice or autocratic overbearing.

Franklin Roosevelt

November 29, 1943

Not since Lincoln has a President so transformed the office. In his four terms, he battled back the Great Depression, remade the federal government as a social safety net and led the country into World War II.

Yet associates still marvel at his Gargantuan appetite for work, his ability to relax in the midst of it, his endless gay optimism. As it has to everyone else, the strain of war has wrenched, strained and hacked at his basic traits of character. But in the President’s case the grind has only polished what was already polished, only toughened what was already steel-strong. He still relishes jokes and wisecracks. He can still drop off for a cat nap anywhere, anytime. He still looks forward to a nightly old-fashioned or two in his study before dinner as a high point of his day. He has grown almost impervious to political criticism. He rarely becomes angry at all—and then it is usually when somebody snipes at him through one of his children.

Harry Truman

January 3, 1949

Portrait by Ernest Hamlin Baker

Truman said the death of Roosevelt felt like a “bull or load of hay” falling on him. But FDR’s Vice President soon found his bearings, overseeing the end of the war and the beginning of an new era.

Harry Truman succeeded in dramatizing himself; to millions of voters he seemed a simple, sincere man fighting against overwhelming odds—fighting a little recklessly perhaps, but always with courage and a high heart. Few men have been able to communicate their personality so completely. He never talked down to his audience. He showed no shadow of pompousness. He introduced his wife as “my boss,” sometimes as “the madam.” “I would rather have peace than be President,” he cried. He never had to remind his audience that he had been a Missouri farmer, a man who could stick a cow for clover bloat and plow the straightest furrow in the county, a small-time businessman who could still twist a tie into a haberdasher’s knot. When he stumbled over a phrase or a name, he would grin broadly and try again. Newsmen snickered and politicians winced. But his audiences smiled sympathetically. They knew just how he felt. “Pour it on, Harry,” they cried, “Give ’em hell!”

Dwight Eisenhower

January 4, 1960

Portrait by Bernard Safran

A Cold War leader at a time of economic boom and falling national debt, Eisenhower approached the end of his two terms as President riding a wave of popularity.

Ike’s faults are those that his countrymen can share and understand, and in his virtues he is more than anything else a repository of traditional U.S. values derived from his boyhood in Abilene, Kans., instilled in him by his fundamentalist parents, drilled into him at West Point, tempered by wartime command, applied to the awesome job of the presidency and expanded to meet the challenges of the cold war. Returning to Abilene in 1952, Dwight Eisenhower spoke of his mother and father. “They were frugal,” he said, “possibly of necessity, because I have found out in later years that we were very poor. But the glory of America is that we didn’t know it then.” In a 1959 speech, he again drew on his memories, going back to his days as an Army subaltern, newly married to Mamie Geneva Doud, when he scrimped to buy a tiny insurance policy. “Well,” he said, “I gave up smoking readymade cigarettes and went to Bull Durham and the papers. I had to make a great many sacrifices ... Yet I still think of the fun we had in working for our own future.” Fiscal responsibility was more than a nostalgic, negative notion with Ike. He saw it as the basis of a positive philosophy of government.

In 1948 everyone expected Thomas Dewey to win, but Truman took the popular vote and 28 states to his rival’s 16 (a third candidate won four)

Photograph by W. Eugene Smith

In a televised address during his showdown with Moscow, Kennedy informed the nation of the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba

Photograph by Ralph Crane

John Kennedy

January 5, 1962

Portrait by Pietro Annigoni

After his first year in office, a Gallup poll showed 78% of the public approved of Kennedy’s job performance—an astronomical number for a time of relative peace.

He was fascinated by the perquisites of his office and his sudden access to the deepest secrets of government. He explored the White House, poked his head into offices, asked secretaries how they were getting along. He propped up pictures of his wife and children in office-wall niches, while Jackie rummaged through the cellar and attic, charmed with the treasures she found there and already determined to make the White House into a “museum of our country’s heritage.” The Kennedy “style” came like a hurricane. For a while, the problems of the world seemed less important than what parties the Kennedys went to, what hairdo Jackie wore. Seldom, perhaps never, has any President had such thorough exposure in so short a time.

Lyndon Johnson

January 5, 1968

Caricature by David Levine

At the end of his presidency, Johnson faced a deteriorating war in Vietnam and a civil rights struggle at home. Three months after this story ran, he announced he would not seek re-election.

Johnson has had less to say about the job than many of his predecessors. But once, in the early days of his presidency, when aides warned him against risking his prestige by fighting for a civil rights bill because the odds were 3 to 2 against its passage, he asked quietly: “What’s the presidency for?” That brief remark spoke volumes about his desire to use the office not simply as a springboard for self-aggrandizement but for the nation’s progress. Unlike Ike, who set up military lines of command and delegated considerable responsibility, Johnson wants to be in on everything. His night reading often a five-inch-thick stack of memos and cables, covers everything from the latest CIA intelligence roundup to a gossipy report on a feud between two Senators. “Not a sparrow falls,” says a former aide, “that he doesn’t know about.”

Richard Nixon

January 3, 1972

Sculpture by Stanley Glaubach

He was hailed for good reasons. But Watergate was yet to come, and his downfall would be swift and brutal, testing the constitutional system and reawakening the courts and Congress as checks on the presidency.

In 1971 President Nixon helped cool national passions. He made his bid for a historic niche on the issues of war and peace and in the business of keeping his nation economically solvent. Perhaps his major accomplishment was simply helping the U.S. to catch up. On the war, on China, on welfare reform, on devaluation, he moved the country to abandon positions long outdated and toward steps long overdue. In doing so, he also destroyed some once sacrosanct myths and shibboleths. The result in the U.S. was a greater sense of reality and of scaled-down expectations; given the temper of the times he inherited, that was mostly to the good. The ultimate judgment of his presidency will depend on how he manages to live within the new reality he himself tried to define—and on whether history accepts his definition.

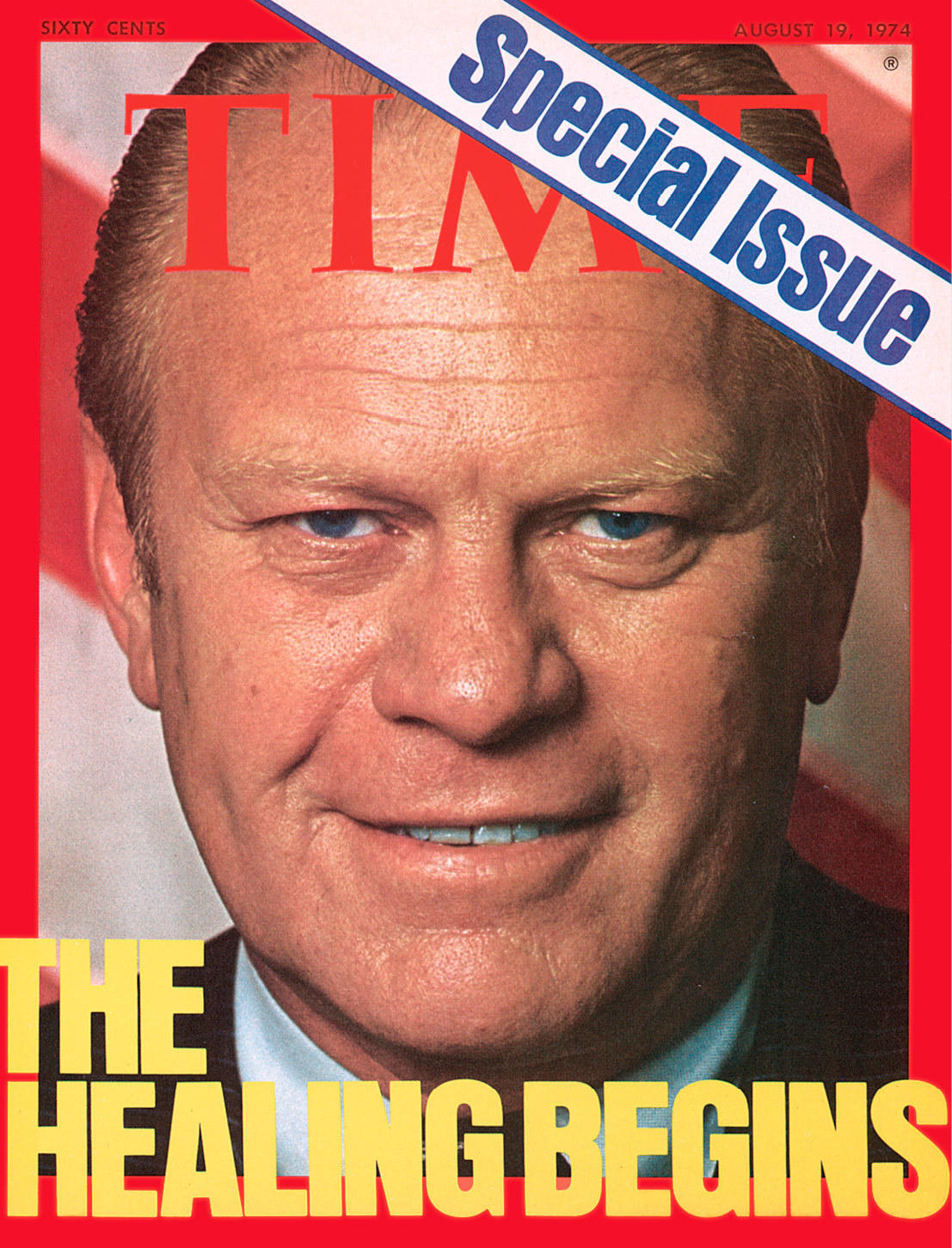

Gerald Ford

August 19, 1974

Photograph by David Hume Kennerly

Ford’s sudden promotion to Commander in Chief came at a time of national crisis, and he approached the job focused on healing the wound that had been left by his predecessor.

In their two-hour meeting that afternoon, Ford was characteristically simple and direct. “I need you,” he told [Secretary of State Henry] Kissinger, stressing that they had known each other for years and that they could probably get along without any trouble. Said Kissinger: “It is my job to get along with you and not your job to get along with me.” The two made plans for messages to go out to all nations, assuring them of the continuity of U.S. foreign policy. That night, after watching Nixon’s resignation speech on television with his family at home, Ford stepped outside ... to speak to reporters and about 100 cheering neighbors. “This is one of the most difficult and very saddest periods, and one of the saddest incidents I’ve ever witnessed,” he said. It was obvious to all that he meant it. “Let me say that I think that the President of the United States has made one of the greatest personal sacrifices for the country and one of the finest personal decisions on behalf of all of us as Americans by his decision to resign.” Ford announced that Kissinger, whom he called “a very great man,” had agreed to stay on as Secretary of State. “I pledge to you tonight” Ford concluded, “as I will pledge tomorrow and in the future my best efforts in cooperation, leadership and dedication to what is good for America and good for the world.”

Jimmy Carter

May 5, 1980

Portrait by Daniel Schwartz

Carter’s single term ended with economic and global crises. His problems came into sharpest relief just before the 1980 campaign with the failure of a rescue mission for kidnapped diplomats in Iran.

The supersecret operation failed dismally. It ended in the desert staging site, some 250 miles short of its target in the capital city. And for the world’s most technologically sophisticated nation, the reason for aborting the rescue effort was particularly painful: three of the eight helicopters assigned to the mission developed electrical or hydraulic malfunctions that rendered them useless. For Carter in particular, and for the U.S. in general, the desert debacle was a military, diplomatic and political fiasco. A once dominant military machine, first humbled in its agonizing standoff in Viet Nam, now looked incapable of keeping its aircraft aloft even when no enemy knew they were there, and even incapable of keeping them from crashing into each other despite four months of practice for their mission. That was embarrassing enough, but the consequences of the mission that failed were far more serious; they affected everything from the future of Jimmy Carter to the future of U.S. relations with its European allies and Japan. While most of Carter’s political foes tactfully withheld criticism, his image as inept had been renewed. Already hurt by mounting economic difficulties at home, the President now had a new embarrassment abroad. The failure in the desert could prove to be a blow to his re-election hopes.

Ronald Reagan

July 7, 1986

Portrait by Birney Lettick

He led the nation during one of the great economic booms of the 20th century and enjoyed the highest second-term approval ratings—and for a longer period—than any other President up to that point.

Ronald Reagan is a sort of masterpiece of American magic—apparently one of the simplest, most uncomplicated creatures alive, and yet a character of rich meanings, of complexities that connect him with the myths and powers of his country in an unprecedented way. Sleight of hand: during a meeting of the Economic Policy Council last year, the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Agriculture started lobbing grenades at each other over a proposal to sell grain to the Soviet Union. Others entered the argument. Voices rose, arms waved. Through it all, Ronald Reagan sat silently, apparently concentrating on picking the black licorice jelly beans from the crystal jar on the table in front of him. Occasionally, he would look up. Once, as he did so, he caught the eye of an aide sitting opposite him at the back of the room. The President winked. The tumult gradually subsided. When it was peaceful again, Reagan looked up, turned to Treasury Secretary James Baker, and said, “What’s the next item, Jim?” It had been a very private wink, but it seemed to its one witness to go beyond the walls of the White House, out over the Rose Garden and well outside the Beltway that surrounds the nation’s capital. It was as if Ronald Reagan had winked at America, sharing the people’s amused disdain for the sort of thing that goes on in Big Government.

George H.W. Bush

January 7, 1991

Photograph by Gregory Heisler

Bush had two competing story lines: success overseas ousting Iraqi forces from Kuwait and economic strain at home. American ambivalence presaged his loss less than two years later.

He often paused in the hideaway office beside his bedroom before a favorite painting of Abraham Lincoln conferring with his generals during the Civil War. “He was tested by fire,” Bush would muse, “and showed his greatness.” And to one friend, Bush wondered aloud how he might be tested, whether he too might be one of the handful of Presidents destined to change the course of history. On Aug. 1 he found out. It was about 8 p.m. in Washington and Bush had gone upstairs for the evening, when an aide brought an urgent message from the White House Situation Room. Iraq had invaded Kuwait. At first, most diplomatic and intelligence analysts believed Saddam Hussein would confine his thrust to long-disputed border areas. But as Bush followed the latest reports ... Iraqi tanks churned into the Kuwaiti capital, forcing the royal family to flee. It was a full-blown takeover. Next morning the world was waiting to hear what Bush had to say about that blatant act of aggression. At 8 ..., he invited reporters in for a brief exchange. “We’re not discussing intervention,” Bush insisted. “I’m not contemplating such action.” He stammered a bit, as he often does when he is tired—or when he does not believe what he is saying. This time it was both. As Bush would later recall, he had made an “almost instantaneous” judgment that the U.S. must intervene.

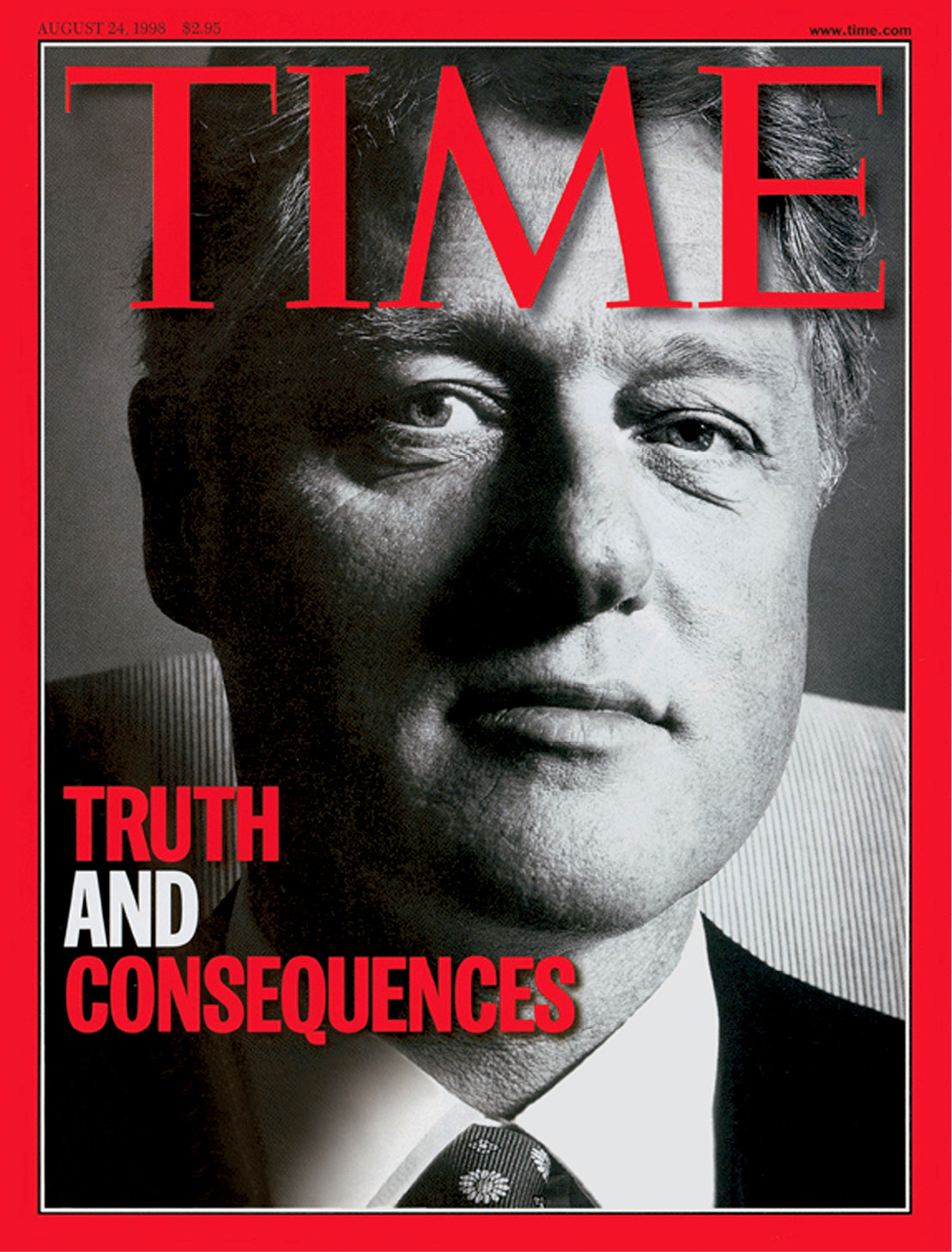

Bill Clinton

August 24, 1998

Photograph by Nigel Parry

After a rocky first term, Clinton easily won re-election with a booming economy and weak opponent. But a personal scandal would return Clinton to crisis mode and a confrontation with Congress.

From its very first days this scandal has divided the nation between those who want to leave Clinton alone and those who want him to pay, between those who think everyone lies about sex—that he has been persecuted just because he is President—and those who think this fate goes with the job. Presidents aren’t like kings, but they aren’t supposed to be like the rest of us either. The office confers a mystic expectation, a combination of Roosevelt’s brains and Johnson’s clout and Reagan’s grace, that helps Presidents persuade Congress and the people to follow their lead. The agony of Clinton’s choice was that his best chance for survival demanded that he declare himself less than we expect a President to be and more like the rest of us after all.

The moment Clinton confesses to anything, he loses some magical powers; his decisions during the past seven months have already cost him some actual powers as well. The shrapnel from this scandal is now embedded in the polity, the culture and the law, and it will take more than the passage of time to dig it out. The wreckage spreads across the whole field of battle: his moral authority, his ability to respond to a crisis, his room to negotiate with a Congress that might soon be his judge, and his ability to get the advice he needs.

George W. Bush

December 1, 2003

Photomontage with an image by Brooks Kraft

Defined by the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, Bush’s presidency unfolded as a series of principled stands that sharply divided the nation. Those divisions consumed much of his second term.

George Bush is the son of a President who couldn’t convince the country that he stood for anything. He succeeded a President whose survival depended on the public’s capacity to divorce what it thought of his personal values from what it thought of his public ones. Bush has done the opposite of both. He has wrapped his presidency in who he is and what he believes. So it’s no surprise that the theme of Bush’s first presidential ad of the campaign is essentially: I, George Bush, am the war against terrorism. “Some are now attacking the President for attacking the terrorists,” the ad suggests darkly. But for many, it’s not so much Bush’s policies or programs that make them adore or despise him, but the very way he carries himself—their sense of George Bush as a man. To some, the way that Bush walks and talks and smiles is the body language of courage and self-assurance, and of someone who shares their values. But to others, it is the swagger and smirk that signals the certainty of the stubbornly simpleminded.

Barack Obama

December 29, 2008

Portrait by Shepard Fairey

After a celebrated campaign, he would assume office in the middle of the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression. His response, and the frustrations that followed, would define his first term.

Crisis has a way of ushering even great events into the past. As Obama has moved with unprecedented speed to build an Administration that would bolster the confidence of a shaken world, his flash and dazzle have faded into the background. In the waning days of his extraordinary year and on the cusp of his presidency what now seems most salient about Obama is the opposite of flashy, the antithesis of rhetoric: he gets things done. He is a man about his business—a Mr. Fix It going to Washington ... We’ve heard fine speechmakers before and read compelling personal narratives. We’ve observed candidates who somehow latch on to just the right moment. Obama was all these when he started his campaign ... But while events undermined those pillars of his candidacy ... Obama has kept on rising.

Being the unelected conjugal partner in the White House requires deft circumspection. In a 1939 cover story on Eleanor Roosevelt, TIME described the First Lady’s modus operandi as follows: “She operates quite apart from the President, behind and beneath what is commonly called ‘politics.’ Stories that she influences his policies and appointments are as untrue as stories that he tries to edit her conduct. She is a one-woman show in herself, requiring the full-time services of three able assistants to stage everything she feels she must.” America’s First Ladies have always had to manage both public appearance and inevitable influence. Some abdicated any role; others found beautifying the White House—or the countryside—to be their way of pressing their husbands’ policies, making the presidency more intimate. But the most successful wives have always managed to be heard, even if not in public. East Wing is East and West Wing is West, but the twain do definitely meet.