Plato’s Menexenus has long posed a difficult and, to some, infuriating riddle. It begins with Socrates describing how he meets the young man Menexenus heading from the Council Chamber in the Athenian Agora. Menexenus tells Socrates that he has been at a meeting at which someone was due to be chosen to give a Funeral Speech, but the selection was left undecided. He says that the decision will be made the following day, and imagines that the speaker selected will be Archinus or Dion. The latter is unknown, but the former was an active politician in 403 BC, which gives the dramatic date of the ‘dialogue’ as somewhere near that date.

Menexenus’s comment is the cue for Socrates to launch into a critique of orators for their hackneyed eulogies:1

Really, Menexenus, dying in battle seems to be a splendid fate in many ways. Even if he died a pauper, a man gets a magnificent funeral, and even if he were a worthless fellow, he wins praise from the lips of accomplished men who do not give extemporised eulogies but speeches prepared long beforehand. And they praise so splendidly, ascribing to every man both merits that he has and others he does not, that with the variety and splendour of their diction they bewitch our souls. And they eulogize the State in every possible fashion, praising those who died in the war and all our ancestors of former times and ourselves who are living still.

As a result, Menexenus, when praised by them I myself feel mightily ennobled. I become someone different, and imagine myself to have become all at once taller and nobler and more handsome. And as I’m generally accompanied by some strangers, who listen along with me, I become in their eyes also all at once more majestic. They also manifestly share in my feelings with regard both to me and to the rest of our City, believing it to be more marvellous than before, owing to the persuasive eloquence of the speaker.

And this majestic feeling remains with me for over three days. The speech and voice of the orator ring in my ears so deeply that it’s scarcely till the fourth or fifth day that I recover and remember that I’m really on earth, whereas I almost imagined myself to be living in the Islands of the Blessed. So expert are our orators!

Menexenus responds to this ironic diatribe by saying that in this case, given the short notice, the speech will probably have to be improvised. Socrates retorts that few speeches are truly improvised, but are generally based on a prepared template. He says that he was himself taught a Funeral Speech by a teacher skilled in the art of rhetoric, who had been the teacher of an orator of no less note than – he gives the name in full to emphasise that distinction – Pericles son of Xanthippus: that teacher was Aspasia.

Socrates proceeds to relay to Menexenus, on the latter’s insistence, the speech that he says he was taught by Aspasia. ‘I was listening to her only yesterday,’ he recounts, ‘as she went through a funeral speech for the audience in question. She had heard the report, you see, that the Athenians were going to select a speaker. So she rehearsed to me the speech in the form she thought it should take, partly improvising and partly using bits that I assume she’d previously composed for the funeral oration given by Pericles. It was fragments of these that she patched together to make her oration.’ Menexenus asks if he can remember Aspasia’s speech and relay it to him verbatim, to which Socrates replies: ‘Yes, I’m sure I can. You see, I was practising it with her as she went along. Once I forgot the words and almost got slapped!’

This is an extraordinary comment for an Athenian man to make, even if it occurs in a scenario that may be wholly imaginary. Plato here allows Socrates not only to concede intellectual authority to Aspasia, but has him draw attention to conditions of close physical intimacy with a woman who is not his wife or relative. Socrates proceeds to give Menexenus a rendition of the speech that Aspasia is supposed to have composed for the Athenians who fell in war.2 The speech is conventional in form and content, and has generally been thought a parody of the genre. It also poses a chronological conundrum: one of the military actions mentioned towards the end of the oration, the Battle of Lechaeum, took place in 390 BC, and the ‘King’s Peace’ of 386 BC is also referred to. These dates fall many years after both Socrates and Aspasia were dead.

What, then, are we to make of this scenario? Does the inclusion of a datable anachronism simply confirm its fictionality? Scholars have almost universally dismissed the genuineness of the occasion, often seeing Menexenus as little more than a Platonic parody of oratorical techniques. But what this strange dialogue also shows, if only incidentally, is that Plato was prepared to present Socrates and Aspasia, albeit at a late stage of their lives, engaging in intimate discussion and collaboration.

Since the chronology is deliberately vexed, perhaps we should recognise that a scenario that can be projected forward in time might also be projected backwards. No other passage in Plato’s voluminous writings mentions any kind of relationship between Socrates and Aspasia. So Menexenus might be read as, among other things, representing a concession by Plato that there had indeed once been an intimate relationship between the two, something to which he was unprepared to give witness in any other dialogue. It bids us take a closer look at the historical background of Aspasia herself.

Enter Aspasia

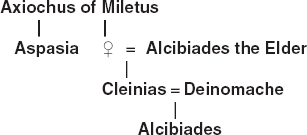

One of the most striking, eloquent, and controversial women of her age, perhaps the most extraordinary woman in all of classical antiquity, Aspasia daughter of Axiochus was just twenty when she sailed to Athens with her sister and her brother-in-law, the elder Alcibiades, in around 450 BC. The family left behind the busy, bustling mercantile Ionian city of Miletus across the Aegean, where Alcibiades the Elder, father of Cleinias and grandfather-to-be of the younger Alcibiades, had been sent from Athens into exile, a victim of political infighting, ten years earlier in 460 BC.

A recently discovered inscription suggests that Aspasia had a family connection to Alcibiades through her father Axiochus as follows:3

What emerges from this is the following picture. While in exile in Miletus, Alcibiades the Elder met Aspasia’s father Axiochus. A wealthy member of the Ionian Greek elite, which had long-standing family connections with Athens, Axiochus would have been happy to marry one of his daughters (whose name is unknown) to Alcibiades the Elder, a member of the deme of Scambonidae; their son Cleinias was to become Pericles’ friend and associate. When Alcibiades the Elder returned from Miletus with his new spouse and their children, he brought with them his wife’s sister Aspasia, perhaps with an eye to arranging for her an illustrious marriage with an Athenian aristocrat.

It was not a good moment to embark on such a project. Just a year earlier, in 451 BC, Pericles had introduced a citizenship law which precluded the sons of non-Athenian wives from becoming Athenian citizens. The law was intended to discourage high-born Athenian men from marrying non-Athenian wives by warranting that such a choice would disadvantage the children of such a union. Athenian citizenship would become an even more exclusive privilege than it had been, and the hoped-for result would be an enhancement of the status of Athenian-born mothers.

Although a non-Athenian, Aspasia, the sister of Alcibiades the Elder’s wife, was a great-aunt to the infant Alcibiades son of Cleinias. So it seems natural that when, three years later in 447 BC, Cleinias was killed at the Battle of Coronea, the glamorous, energetic, unmarried young woman from across the water would have been involved in supporting the youngster’s transition into his new household, that of his guardian Pericles. It may even be precisely at that point, and with that in mind, that she was first brought into the household of Athens’ leader.

The fathers of Miletus appear to have been more open to educating their daughters than were the Athenians. In addition to beauty and character, Aspasia had high educational attainments. Pericles was twice her age, and already had two children from an earlier marriage; but ten years had passed since he had divorced his wife.4 Now the youthful Aspasia captivated him with her looks, charm, and intellect; and around 445 BC she joined Pericles as his wife in effect, if not in name.5 It would have been hard for Pericles to circumvent his own law and establish her as his legal spouse. The comic poets gleefully vilified the union, calling Aspasia a ‘harlot’ (pornē) and ‘concubine’ (pallakē) and their son Pericles Junior a ‘bastard’ (nothos).

Later authors report, as we have seen, that Pericles was so in love with Aspasia that throughout their relationship he would not let a day pass without kissing her in the morning and at night. They became adoring and inseparable partners until Pericles’ death from the plague sixteen years later, in 429 BC.6 Honoured above all women by Pericles, honoured by and honouring the very man nicknamed ‘Zeus’ in comic drama and popular parlance: it would be hard for alert readers of Plato’s Symposium not to make the connection with the fictional Diotima, the character whose name means ‘honoured by Zeus’ and who Socrates could claim taught him ‘all I know about love’.

Aspasia’s reputation

Ancient authors often speak of Aspasia in derogatory terms, not least because of the evidence from contemporary comic poets such as Cratinus and Hermippus, whose plays reflected popular resentment against her and Pericles. The comedians dubbed her a ‘whore’ and a ‘dog-eyed concubine’, while the biographer Plutarch compared her to Thargelia, the Ionian courtesan who seduced powerful men and wielded influence over them. At best, therefore, Aspasia has been considered a hetaira, a high-class courtesan; though it is telling that this less pejorative designation is favoured by modern scholars seeking to accord Aspasia a more ‘respectable’ status rather than by the ancient sources themselves.

Stemming mainly from non-Athenian backgrounds, hetairai were the female entertainers of high society; they were often well educated and financially independent, and in addition to selling sexual favours might earn their living by providing refined forms of diversion at symposia. They were well enough remunerated for a tax to be levied on their profession, and some even became wealthy as the proprietors of brothels. It was to this latter category that some censorious Athenians might have been inclined to assign Aspasia.

Scholars have accepted this attribution as a historical fact despite the lack of confirmation in ancient writings for Aspasia’s status as a hetaira. Aspasia’s upper-class family connections – as the daughter of Axiochus she was after all, of Alcmaeonid stock – and her respected status in Pericles’ circle reveal it to be nothing more than a misogynistic slander. The scurrilous accusations of comedy cannot be taken, as they so often have been, at face value. An egregious instance is the report by Plutarch that Aspasia was actually put on trial for alleged ‘impiety’ and for ‘procuring free-born women for Pericles’. Not only is it doubtful that Athenian law of the time accorded women – let alone those of non-Athenian birth – sufficient status to merit being brought to trial on such charges, but the accuser in this case was said to be none other than the one-eyed comic poet Hermippus, the author of a play lampooning Pericles as a sex-maniac. The report can be nothing but a garbled interpretation of a scene in comedy or of the kind of ‘accusation’ regularly levelled against Aspasia (no doubt as a substitute for their real target, Pericles) by the comic playwrights.7

It is noteworthy that Plato and Xenophon refer to Aspasia in a manner that is far more respectful than they would have had she been a hetaira. Plato’s Aspasia is an admirable, self-confident woman, whose eloquence and intellect entitled her to act as an instructor to both Pericles and Socrates, two of the most remarkable speakers of the age. In a passage of Xenophon, when Socrates is asked about how a wife may come to be educated, he replies: ‘I will introduce Aspasia to you, since she knows much more about the matter than I do, and she will explain everything to you.’

Commentators have dismissed such passages with incredulity, largely because of their insistence that Aspasia was a courtesan.8 But in a lost work entitled Aspasia by Plato’s contemporary Aeschines of Sphettus, Aspasia is portrayed as someone Socrates is happy to recommend as a teacher, presumably of oratorical technique, to the son of the wealthy Callias. In a section of that book, a discussion takes place between Aspasia and the wife of a certain Xenophon (probably not the historian), and later with Xenophon himself. Using a recognisably Socratic style of questioning, Aspasia leads both her interlocutors to understand that the secret of obtaining the best or most virtuous of spouses is to be such a spouse oneself. Her focus on the aim of being ‘the best’ emphasises, in what we might also recognise as a Socratic mode of thinking, the moral aspect of achieving marital success. Plutarch reports that Socrates occasionally went to Aspasia together with his friends and their wives to seek Aspasia’s advice and to hear her speak about ‘matters of love’ (erōtika). Albeit she is assigned in these accounts something like the role of a relationship coach and matchmaker, these testimonies offer striking confirmation that Aspasia was known for her interest in discoursing on love and – like Diotima in Plato’s Symposium – for her unusual eloquence and expertise in that particular area.9

Plato’s portrayal in Menexenus of the older Aspasia giving Socrates instruction seems to belie an earlier inclination, shared by Xenophon, to conceal any explicit indication that Aspasia ever had a close acquaintance with Socrates. If such a relationship is accepted, the strong likelihood is that it was formed much earlier, when the two first met in Pericles’ circle in their twenties.

After Pericles’ death in 429 BC, Aspasia lived with (‘married’, according to an ancient commentator) a wealthy Athenian politician called Lysicles, from whom she bore a son. Lysicles, too, is spoken of disparagingly in comedy – Aristophanes calls him a ‘sheep-dealer’ – but given that he served in the role of general, he will have been a citizen of some status and possibly an acquaintance of the late Pericles. Lysicles was killed in action in Asia Minor shortly after the marriage, in 428 BC. Thereafter we hear little more about Aspasia’s activities, until her appearance as an older woman in Plato’s Menexenus.

The exception to the silence is Aristophanes’ comedy Acharnians, performed in 425 BC, four years after Pericles’ death. There Aspasia is savaged in comic style for allegedly being the prime cause of the Peloponnesian War – rather as Helen was considered responsible for the Trojan War, and just as Aspasia herself had previously been blamed for instigating Pericles’ assault on Samos in 440 BC. The comedy blames her, this time, for prompting Pericles’ Megarian Decree in retaliation for the kidnap by Megarians of two prostitutes from her house of ill repute. The decree, which some have thought imposed restrictions on Megara from trading with Athens or its allies, was said to have sparked the war.10

The opprobrium directed at Aspasia thus lasted for decades after her union with Pericles in the 440s; and Plato and Xenophon will have been concerned that Socrates should not be tainted by it. Moreover, in view of the fact that Aspasia and Pericles were together by around 445 BC (Pericles Junior was born not later than 437 BC), Socrates’ biographers would not have wished, writing over half a century after that time, to depict a close liaison at that period between Socrates and Aspasia, even had they known or suspected it to be the case. After Aspasia married Pericles, Socrates will have had to moderate, if not wholly renounce, any relationship with her, if only to avoid, for the sake of all concerned, the suspicion that they had ever shared a more intimate personal history.

Aspasia and Socrates

In 450 BC Socrates, a direct contemporary of Aspasia’s, was shortly to turn twenty. As the pupil and friend of Archelaus he will already have been known for a number of years to people in Pericles’ entourage such as Anaxagoras. As the son of the successful stonemason Sophroniscus, he will have come to the attention of men like Ictinus, Callicrates, and Pheidias, the architects and designers of the Parthenon who were also the close associates of Athens’ leading political figure.

We are not told whether Socrates met Aspasia and associated with her in the years between her arrival at Athens and her marriage to Pericles. Those years certainly offered the opportunity for the two to have become acquainted. Whether or not Socrates fought at the Battle of Coronea and saw in person the death of Pericles’ friend Cleinias that year, he will have been drawn yet further into Pericles’ circle a few years later – as a tutor chosen to guide the future path of the young Alcibiades. If Aspasia and Socrates had not already come into contact in the milieu of Pericles when Aspasia arrived in Athens with her family from Miletus in 450 BC, they would have shared a concern for the welfare and education of Alcibiades after he lost his father in 447 BC.

Socrates and Aspasia were kindred spirits. Both clever, eloquent, and argumentative, they were unusual and controversial figures within their social milieus. The Menexenus is the only source that gives us any explicit indication, however hard it may be to interpret correctly, of a close acquaintance between Socrates and Aspasia. Any further conjectures must arise from circumstantial evidence, and by reading between the lines of what Plato and Xenophon tell us. Such readings may be what inspired ancient authors from at least as early as the fourth century BC to assume that there had been an amorous relationship between the two. A learned pupil of Aristotle, Clearchus of Soli, writes that Pericles fell in love with Aspasia ‘who had formerly been a companion of Socrates’; and a poem by Hermesianax (third century BC) speaks of Socrates’ ‘unquenchable passion’ for Aspasia.11 As we have seen, such a liaison may underlie the account of love attributed to Diotima by Socrates in Plato’s Symposium.

Might Socrates have fallen in love with the extraordinary Aspasia, only to know that his love could never be fulfilled? There would have been obstacles in the way of a liaison, including Socrates’ own concern about his inner voices, his proneness to cataleptic seizures, and his inclination to pursue a path in life that might make him less than suitable to become the husband of a clever and ambitious young woman. If Socrates had ever thought of Aspasia as a potential lover and partner, the possibility would have been foreclosed once Athens’ most powerful man had set his heart upon her. Perhaps, in seeking to assuage Socrates’ disappointment, the eloquent Aspasia urged him to ask himself what true love really means, and then proposed something like the doctrine allegedly imparted by Diotima in Plato’s Symposium to Socrates in his younger days: that physical desire is only the starting-point for true love, and that particular, personal concerns should ultimately yield to higher goals.

If such ideas and expressions are to be attributed to Aspasia, they have a momentous implication for the history of thought. The principles that Diotima’s doctrine imply are central to the philosophy as well as to the way of life that Socrates was to espouse: that we need to define our terms before we can hope to know what they entail in practice; that the physical realm can and should be put aside in favour of higher ideals; that the education of the soul, not the gratification of the body, is love’s paramount duty; and that the particular should be subordinated to the general, the transient to the permanent, and the worldly to the ideal. Classicist Mary Lefkowitz has observed:

Socrates would be an important figure in the history of philosophy even if all we knew about him was what Aristotle tells us: ‘He occupied himself with ethics even though he said nothing about the universe, but in the course of his activities he searched for the general (to katholou) and was the first to understand about the concept of boundaries (horismōn)’ (Metaphysics 987b.1–4). Poets and thinkers before him had thought about ethics. But what made Socrates different is that he was able to devise a process for discovering it that caused him to move away from particulars to general definitions. Without that significant step forward in thought, Plato could never have devised his theory of forms, and Aristotle could not have written his treatises on ethics.12

In so far as Socrates created a philosophical method distinct from that of his alleged female mentor – one that involved continually questioning and eliciting answers rather than giving instruction, as Diotima does – it might have emerged in express contradistinction to a procedure that to his mind could only gesture at the elusive truth but could never attain it.13 But if the stimulus to Socrates’ adoption of his philosophical perspectives and procedures was the woman who first taught him ‘all about love’, we should recognise that Aspasia was not just a dynamic and unusually clever woman in her own right, but an intellectual midwife whose ideas, no less than what Socrates and his successors were to make of them, helped to give birth to European philosophy.

Socrates in the Symposium is happy to admit that he learned his doctrine of love from ‘Diotima’; but had Plato supposed that Aspasia might be credited as the crucial inspiration for Socrates’ philosophical thinking, he would have been reluctant to attribute such influence to her directly. In any case, Aspasia’s choice to be with Pericles may have led to a cooling of relations between her and Socrates. She may have come to share Pericles’ disapproval, expressed in general terms in the Periclean Funeral Speech which she is alleged in Menexenus to have composed, of Socrates’ refusal to involve himself in his city’s political life. But in view of the confluence of chronological, social, and intellectual factors, it becomes an attractive and compelling possibility that the advent of Aspasia into the young Socrates’ life around 450 BC is the moment for us to find, if only for a short while, an appealing and credible image of Socrates in love.