Chapter Two

Efficient Market Theory and Its Discontents

Out with the Old, In with the New—Overhauling the 60/40 Portfolio

Before we dive into our alternative world, we first want to talk about ways to tune up your basic stock and bond portfolio so you are maximizing the expected return for the risks you are taking. If you are like most people, your current portfolio would get comments from the teacher like “Needs work” or “Not working up to abilities.”

Example: Your authors were having lunch at Nonna in Beverly Hills, when a man we had never met comes up to the table clutching a thick envelope from a well-known brokerage firm. Introducing himself, he pulls out his statement—about 50 pages long—and asks us what we think of his portfolio. This is the equivalent of the free curbside consultation that doctors are subjected to, now transplanted to finance. We asked him what he does for a living. He’s a business executive and has an M.B.A. from Stanford. If this guy can’t figure out his brokerage statements, what chance do the rest of us have?

Thumbing through the statement, we find page after page of stocks. Abbott Labs . . . Abercrombie & Fitch . . . Altria . . . and so on, down the alphabet. What do we say? Do we opine about each ticker, pro and con?

No. Not necessary.

Right away, we know that this guy is following the strategy of individual stock picking, one that seldom provides the best returns. It comes as no surprise that even by holding each page up to the light we can find no reporting anywhere of his returns, let alone of how those returns compare to standard market benchmarks. It is almost as if his high-priced brokerage was deliberately trying to snow him with data while withholding the very information he would need to make an intelligent decision about the course of his investing.

There are a lot of investors out there in his position. They are paying 1 or 2 percent every year in fees for a “wrap” account, but they have little idea how they are really doing.

This brings us to the key, life-changing insight from Vanguard’s John Bogle. Active stock picking—the kind that gives you the long printout of ever-changing individual positions—is an expensive game. Managers are expensive, research is expensive, commissions are expensive, and taxes are expensive. After all of these are subtracted from your returns, you are better off simply taking a free ride on the back of the stock market by buying an index fund and leaving the active trading to others. To be sure, some managers will beat the market, but few have demonstrated any long-term ability in doing so. For those who do, their success proves their undoing, as they soon are flooded with more hot money from new investors than they know how to invest intelligently. Meanwhile, trying to discover these genius active managers before they beat the market is a study in frustration.

Bogle discovered that the passive index fund buy-and-hold investor generally beats the active investor by a shockingly large margin. Study after study has confirmed the wisdom of holding the whole market, staying invested through thick and thin, and minimizing all frictional costs. While over any one or two years the margin of the advantage may be small or even negative, over a 20-year period your chances of beating the market by picking active managers versus using a low expense, passive, market index fund are only about 15 percent. Over an investment lifetime, this advantage amounts to a fortune. You are taking a lot of money that was going to be transferred from you to the financial services industry and putting it back in your pocket. By switching from active stock picking to a passive portfolio of index funds, you promote yourself from someone who uses a strategy that usually does not work to someone who uses a strategy that consistently does. Anyone who tells you otherwise either has not read the data, or else has a financial stake in your coming to a different conclusion.

This is the paradox: You can spend a few minutes every year managing a passive index portfolio and beat about 85 percent of investors over the long run, or you can devote every minute of your spare time to picking stocks and get a few good hits here and there but end up underperforming the market, as an honest accounting of your performance would reveal. This is not a game worth playing. It is especially not a good use of your time.

It’s relatively easy to bring more sanity to your financial life. All you have to do is invest in a few broad market index funds. This way, you take on the risks of the market, and you earn the returns of the market, less the very slight expenses of owning the funds. A U.S. total stock market index fund (ticker: VTI), a total international stock index fund (ticker: VEU), and a total bond market index fund (ticker: BND) cover all your needs. That’s all, folks! If someone robs this book from you at gunpoint right now, and that is your only takeaway, you’ll be way ahead of the crowd.

Is that all there is? No, there are a few things you can do at the margins to further increase your returns.

Exploiting Market Anomalies for Fun and Profit

Academic researchers Eugene Fama and Ken French studied the long-term returns from stock market investing and concluded that certain strategies have historically delivered greater returns than has the stock market as a whole. For example, value investors (investors who buy stocks that sell at a low multiple of their underlying economic value) do better than growth investors. Growth investors buy the stocks that people love, but precisely because these companies are so popular, people tend to overpay for them. This means that in aggregate their long-term returns won’t be as good. In comparison, value stock pickers buy companies that are unloved and possibly in some distress, as reflected by their higher book values, higher dividend yields, and earnings that must be used to entice investors. Often they will turn out to be duds, but at least investors didn’t overpay. The earnings surprises for value stocks occur more often on the upside. Is this finding valuable? According to Fama/French’s data, $1 invested in large U.S. growth stocks in 1926 grew to be worth $1,647 in 2010. One dollar invested in large U.S. value stocks in 1926 grew to be worth $4,599 over the same period.

A second market anomaly is that small company stocks tend to do better than large company stocks. Some of them disappear, but others will grow into the next Microsoft. It’s impossible to tell which is which, so owning a whole basket of small company stocks is necessary. Does this work? Let’s turn to the Fama/French data set once more. One dollar invested in large U.S. companies in 1926 grew to $2,436 in 2010. One dollar invested in small U.S. companies grew to be worth $13,666. You don’t need to be a statistician to see that these are meaningful differences.

A third market anomaly is that low beta stocks perform better than expected on a risk-adjusted basis. These are stocks that do not respond to movements in the larger stock market with as much volatility as other companies do. We think that the best explanation of this concept comes from John Maynard Keynes, who was a highly successful investor as well as a brilliant economist. Writing in his General Theory, Keynes despaired that at the end of the day all our careful calculations about the future earnings of companies can fall apart like a cheap suit. It is very difficult to come up with a reliable value today for a company’s future earnings. Compounding this problem is that most people—businessmen and investors alike—are in it for the excitement of speculation and the chance to get rich, which rouses their “animal spirits” and causes them to get too excited about future prospects not exactly in the bank yet.

However, not all companies are equally vulnerable to this exaggeration. There are some companies for which we have a clearer idea of their prospects than we do for others. They have well-established business models and earn money steadily. We can’t be 100 percent sure, of course, but we can estimate more reliably the earnings of a Consolidated Edison over the next five years than we can for Google. This means there will be less emotion packaged into the price of Con Ed’s stock than there is in Google’s, which is more speculative and dependent on future growth projections coming true. Companies like Con Ed are not going to bounce around as much in response to general market events. We might be wrong about this one or that one, but it’s unlikely that we would be wrong on average about a basket of such companies. We are less likely to overpay for them, which means that our returns should be better in the long run. The real problem in stock investing comes from overpaying.

A classic low beta stock is Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Since Buffett and his sidekick, Charlie Munger, take little active role in running the subsidiaries of this holding company, they look for relatively idiot-proof businesses when making acquisitions. Almost any of the companies they buy could have been in business 100 years ago. Coca-Cola. Candy. Insurance. Trains. The classic low beta stocks are often from the consumer staple, utility, and health care sectors, where there is a constant demand for everyday products that get used up quickly and need to be replaced. Over time, their returns stack up like those of the market as a whole, but with less volatility. It’s not that they do so well; it’s that more speculative stocks tend to disappoint, as does speculation in general.

But wait! Haven’t we just contradicted ourselves? On the one hand, we maintain that markets are extremely efficient and that all available pertinent information is speedily processed into the price of stocks. This supports the whole idea of index-based investing. There is no better estimate of the price of the S&P 500 index than the price it is selling at right now. If individual market participants don’t have special insights into the prices of stocks that are superior to those of all investors in the world already distilled into those prices, the least bad way to invest is just to own the whole stock market by using a cheap index fund and be done with it.

However, now we are saying that there are these special factors we can exploit and beat the market. People have known about these market anomalies for years. Why haven’t they disappeared? Why doesn’t everyone buy value, small, and low beta stocks? The answer seems to be market psychology. Psychology seems to lie behind all the ways that potentially improve stock market returns.

Psychology seems to lie behind all the ways that potentially improve stock market returns.

- Ordinary investors are seriously overconfident of their ability to beat the market, and so they gamble to pick winning stocks. This rarely works. This gives the edge to index funds, which don’t bother to pick stocks and just own the whole market, which is less likely to be overpriced (unless the whole market is overpriced).

- Investors love to speculate on glamour companies so they overpay for growth stocks, which lose out over time to “little engine that could” value stocks.

- Investors enjoy the familiarity of owning the big name brand companies everyone has heard of, and that attention raises the market price. They pass on the less familiar, less liquid small stocks that outperform them over time in aggregate because they are cheaper in the first place.

- Investors eschew boring, old-fashioned businesses that are past their sell date in favor of emotional companies, and so they undervalue low beta stocks.

If true, this is good news, because it means that these effects are not going away anytime soon. There are plenty of stooges like us who are consistently going to fall for the market’s head fakes. Since these anomalies seem to be grounded in the foibles of human nature, we should be able to make money off them for a long time to come—or so we hope.

Fortunately, there are many mutual funds that let us capture these recognized anomalies (some call them special risk factors). What funds would we use?

Value and Small Company Stocks

Here the world splits into two types of investors: people—often high-net-worth types—who have investment advisors with access to Dimensional Funds (DFA), and people who prefer to do it themselves. We will address both groups.

Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) is a mutual fund company started by some professors and others from the University of Chicago, where much of the original work analyzing historical stock market returns was done. DFA subscribes to the passive, market-wide investing model à la Bogle, but believes that returns can be improved by tilting their portfolio to include more small company and value stocks. Their funds are exceedingly well thought out and their returns have been excellent, but you need to go through the intermediary of a financial advisor to access them. DFA regards “hot money” as anathema and uses investment advisors as gate keepers to make sure they only let in patient, long-term investors. While their expenses are reasonably low, the need for an advisor adds another layer of fees to acquiring their funds.

Advisors who use Dimensional Funds could buy DFA Global Equity Institutional Portfolio (ticker: DGEIX), which wraps up the entire equity investment world into a ball using Dimensional’s trademark small company/value tilt. In practice, most advisors will slice and dice this further by region: U.S. Equity, Foreign Developed Markets, Emerging Markets, and so on.

Do-it-yourselfers can capture the small/value premiums by using the fundamental-weighted Powershares FTSE RAFI portfolios: two for the U.S. (tickers: PRF and PRFZ, covering large and small cap stocks), two for foreign developed markets (tickers: PXF and PDN, also covering large and small cap foreign stocks), and one for the emerging markets (ticker: PXH). If you equally weight these five funds in your portfolio you come remarkably close to matching the U.S./Foreign Developed/Emerging Market weights as they exist in the global economy, although most U.S. investors prefer to have most of their stocks in U.S. companies.

Low Beta Stocks

Unfortunately, there is not a single mutual fund specializing in low beta stocks. Therefore, we are going to have to access this effect using low beta stocks and sector funds. Even DFA does not have an offering in this space.

As mentioned previously, our favorite low beta stock is Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (ticker: BRKB). It is like a mutual fund all by itself, since it is essentially a holding company for many other companies. We could round this out by buying low beta global sector funds: iShares Global Consumer Staples (ticker: KXI), iShares Global Health Care (ticker: IXJ), and iShares Global Utilities (ticker: JXI).

How much should we use in the way of low beta stocks? We have to remember that these will not beat the market when the stock market is racing upwards, but they help limit risk when the market corrects. Let’s say our baseline portfolio is 50 percent United States, 40 percent foreign developed markets, and 10 percent emerging markets, all with a small and value company tilt. Reserving 5 to 10 percent of the equity total for low beta stocks should give us slightly higher risk-adjusted returns than a portfolio that was benchmarked to the standard index funds at those weights. If some enterprising mutual fund company would create an inexpensive low beta index fund (hint, hint), we might recommend a higher allocation. Unfortunately, mutual fund companies are in business to make money, and there’s nothing sexy to market with a low beta stock fund.

This brings us to the 40 part of the 60/40: bonds. The bond market is ruthlessly efficient and there are no special anomalies to exploit here. Bonds are also more democratic, in that retail investors can typically do just as well as institutional investors by buying cheap bond index funds. Bonds expose us to two sources of risk that investors historically have been paid to bear: term risk and credit risk.

Term risk means that investors who lend money for a long time expect to be paid more than investors who lend money for a short time. That is because over a longer period of time there is a greater risk that interest rates will rise from what they are today, lowering the value of our bond in the process. Consider the plight of an investor in this situation: If the bond he bought pays a 5 percent coupon, but interest rates have risen since he bought it and new bonds today pay 10 percent, his bond simply isn’t going to be worth as much as the prices of the two income streams that the bonds represent equilibrate. There is also the risk that inflation will erode the purchasing power of his coupons and the return of principal, making them worth progressively less than the more expensive dollars that he originally lent to the bond issuer. The longer the bond’s maturity, the greater the chance that inflation and/or rising interest rates (which often go together) will erode the value of his investment. This means investors usually get paid more in yield the longer the term for which they are lending their money.

Credit risk means that some borrowers are more likely to default on their repayments than others. Investors who take a bigger gamble on getting paid back expect to be paid more than those who lend money to borrowers whose repayment is certain. You are in this situation when you apply for a mortgage. If your credit score is good, you will pay a lower rate of interest than will your deadbeat brother-in-law.

As we go out in years until maturity and down in grades of credit quality, the risks—and potentially the rewards—of our bond investment go up. Interestingly, though, we soon reach a point of diminishing returns along both dimensions. Very long maturity bonds (say, 30 years) are much more volatile than intermediate maturity bonds, while offering only slightly more yield in compensation. High yield (“junk”) bonds of low credit quality usually pay little if any more than investment grade bonds after accounting for defaults.

What to Buy

While some people buy bonds to produce a stream of income, many investors use bonds simply to reduce the volatility of their stock portfolios to where they can sleep through the night.

To lower portfolio volatility, we want to use:

- Short-duration, high quality bonds: The iShares Barclays 1–3 Year Treasury Bond ETF (ticker: SHY) gets you U.S. Treasuries at 1.9 year’s duration for the price of a 0.15 percent expense ratio annually. These work because there is very little default risk, and the short duration limits the interest rate risk. For investors in the higher tax brackets who put bonds in their taxable accounts, short maturity municipal bonds would be considered safe: Vanguard’s Short-Term Tax-Exempt Fund (ticker: VWSTX, other share classes available) give you 1.2 years in duration of AA-rated bonds for 0.20 percent in annual expenses.

- Inflation-indexed bonds: Inflation-indexed bonds have even lower correlations to stocks than Treasuries do, because in addition to controlling for default and maturity risk, they also take out inflation risk. Their payout is adjusted according to the Consumer Price Index every year. This means they provide even better volatility control. iShares Barclays TIPs Fund (ticker: TIP) is a good answer here, especially for tax-deferred accounts.

- Total Bond Market Index Fund: Many 401(k) plans have some variant of a total bond market index fund among their offerings. This fund takes more credit and interest rate risk than the ones above, but all things considered it still may be your best choice. Since bonds are tax-inefficient, this is a good use of your tax-sheltered account, and the bond market index fund will usually be one of the least overpriced selections on the menu.

A Risk-Balanced Bond Portfolio

The idea of using bonds as above to put a lid on overall portfolio volatility works best for someone who is looking to get his returns from stocks—in other words, someone using the old-school 60/40. Another way is to use fixed income as a source of return in its own right. To do this, we would expand our bond universe to include four types of bonds and expose ourselves to four risk factors:

1. Maturity risk (Treasury bonds)

2. Credit risk (corporate bonds)

3. Inflation risk (inflation-indexed bonds)

4. Currency risk (unhedged foreign sovereign bonds)

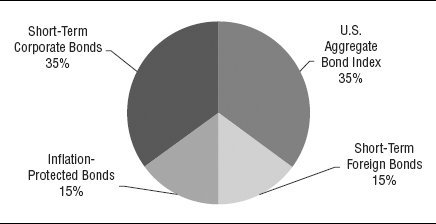

Phil has designed a bond portfolio that tries to spread its risks evenly among these. It looks like Figure 2.1. It is not the final word on the subject, but it’s a start.

Figure 2.1 A Risk-Balanced Bond Portfolio

This portfolio is still short in maturity and high in credit quality, but it is more diversified and has higher projected returns and risks than the all-short-term bonds approach above. We are exposing ourselves to more risks on the bond side, either just because we feel like it, or possibly because we intend to create a portfolio with more bond-centered risks and less equity risk. This is still a relatively low dose of risk, but with the bond market in the state it is in today, we wouldn’t recommend taking on more unless you are personally a bond vigilante. Using the bond portfolio above we estimate that we could change overall allocation from 60/40 stocks/bonds to 55/45 and be at the same place with our risks and returns, just by spreading our risks around a little bit more.

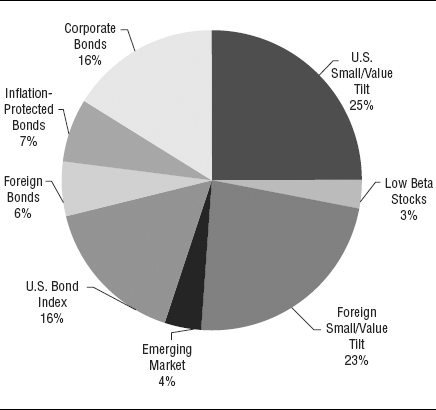

All these various asset classes are the building blocks of a more efficient stock-and-bond portfolio, 60/40 or otherwise. Figure 2.2 shows how they might fit together in a souped-up portfolio—cranked to 55/45. We are not recommending this particular portfolio so much as showing you what one interpretation of this dream might look like. There are many possible interpretations of this dream and many will be better than this one.

Figure 2.2 A Better 60/40?

Luck is a terrible strategy.

The other thing to keep in mind always and everywhere is that we can control strategy but the outcome is in the hand of the gods. You can spend all your money on lottery tickets and if you win the Super Powerball lottery you will become rich overnight. That doesn’t mean buying lottery tickets with your money was a smart strategy or that you are some kind of genius—it simply means you were lucky. Luck, however, is a terrible strategy. Over time, we hope that having a good strategy will converge with a fortunate outcome but, cruelly, there are no guarantees.

The Alternative Reality

To tune up your conventional stock portfolio, dump whatever you are doing and invest in a few broad-spectrum market index funds. If you want to do more than this, tilt your portfolio toward value, small company, and low beta stocks. In doing so, you improve your long-term expected performance, but be aware that you will also experience years when you will underperform the benchmark indices while on the road to Shangri-La. In the future, there may be vehicles to exploit other market anomalies as well.

When it comes to the bond side of your portfolio, you reach a fork in the road. If you just want to control volatility, buy all short-term or inflation-protected bonds and look to the stock market for your returns. If you want to do more than this, take a bit more credit and maturity risk and tilt your overall portfolio more to the bond side.

We will circle back to the overall portfolio allocation—conventional investments plus alternatives—in the last chapter of this book.