VI

I Can Guide a Plough …

Rural Life and Occupations

I Can Guide a Plough …

Rural Life and Occupations

The pastoral song is fairly frequent, especially in the southern counties of England. Its chief theme is the joys of country life. Such are the songs in which the ploughman is the chief personage, and one who glories in his calling … Then there are the sheep-shearing songs … Harvest home songs too are not lacking.

Frank Kidson and Mary Neal, English Folk-Song and Dance (1915), pp. 60–61

It is not surprising that country life and rural affairs feature so strongly in the folk-song repertoire. Not only did many of the songs originate in a time when the majority of the population lived in the countryside (i.e. before 1850), but the Victorian and Edwardian enthusiasts worked mainly in rural areas, and indeed they often used ‘country song’ as a synonym for ‘folk song’. But many of the songs actually originated in towns, written either for the predominately urban broadside trade or as pastoral ditties for pleasure gardens and other commercial entertainment venues, and the view of country life portrayed in folk song is not, on the whole, a realistic one.

Sociologists dubbed the twentieth-century farm employee ‘the deferential worker’, and earlier generations (notwithstanding occasional outbursts such as the ‘Captain Swing’ riots in the 1830s) appear to have been similarly unprotesting. There are exceptions, but the most well-known folk songs about farmwork (‘All Jolly Fellows Who Follow the Plough’, No. 91, and ‘The Farmer’s Boy’, No. 94) are not critical or complaining. In England, there is little evidence of the ‘bothy ballad’ type of song which occurs frequently in Scottish tradition – songs that feature scathing comments on working conditions in general and even on specific farms and farmers. Pride in skilled work and contentment with one’s lot is the more usual tone in England. It is perhaps curious that even parodies of the rural worker like ‘Buttercup Joe’ (No. 93) were adopted so enthusiastically by country folk, but they certainly were.

Harvest homes and other rural gatherings tied to the rhythms of the agricultural year were also noted as places where singing was expected and encouraged, and a high proportion of the songs performed in these contexts championed and celebrated rural life.

There is nothing particularly rural about drinking songs, of which there are many, although they may have had a particular resonance if sung in places where the barley or the hops were actually grown.

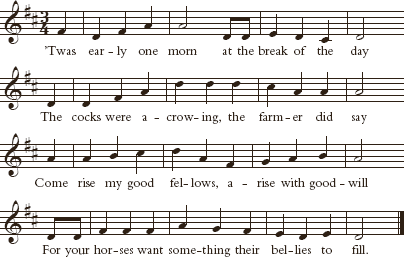

91

All Jolly Fellows Who Follow the Plough

’Twas early one morn at the break of the day

The cocks were a-crowing, the farmer did say

Come rise my good fellows, arise with goodwill

For your horses want something their bellies to fill.

When four o’clock comes then up we do rise

And into the stable, boys, merrily flies

With a-rubbing and a-scrubbing our horses I’ll vow

We’re all jolly fellows who follow the plough.

When five o’clock comes at breakfast we meet

With beef, pork and bread, boys, so merrily eat

With a piece in our pockets I’ll swear and I’ll vow

We’re all jolly fellows who follow the plough.

When six o’clock comes then out we do go

To see which of us a straight furrow could hold

In all kinds of weather I’ll swear and I’ll vow

We’re all jolly fellows who follow the plough.

Our master came to us and this he did say

‘What have you been doing, boys, all this long day?

You haven’t ploughed an acre, I’ll swear and I’ll vow

You’re all idle fellows who follow the plough.’

I turned myself round and made this reply

‘Yes we have ploughed an acre, you’re telling a lie

We have ploughed an acre, I’ll swear and I’ll vow

We’re all jolly fellows who follow the plough.’

Our master turned round and laughed at the joke

‘It’s half past two o’clock, boys, it’s time to unyoke

Unharness your horses and scrub them down well

And I’ll give you a jug of the very best ale.’

So come all ye plough lads, where’er you may be

Never fear your master, take this advice from me

No, never fear your master, I’ll swear and I’ll vow

We’re all jolly fellows who follow the plough.

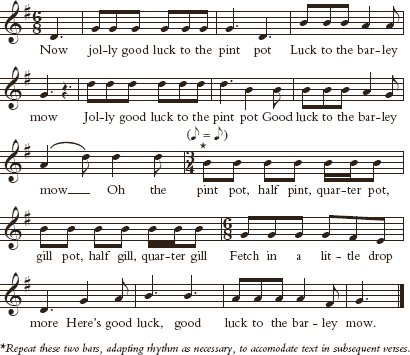

92

The Barley Mow

Now jolly good luck to the pint pot

Luck to the barley mow

Jolly good luck to the pint pot

Good luck to the barley mow

Oh the pint pot, half pint, gill pot, half gill, quarter gill

Fetch in a little drop more

Here’s good luck, good luck to the barley mow.

Now jolly good luck to the quart pot

Luck to the barley mow

Jolly good luck to the quart pot

Good luck to the barley mow

Oh the quart pot, pint pot, half pint, gill pot, half gill, quarter gill

Fetch in a little drop more

Here’s good luck, good luck, to the barley mow.

Now jolly good luck to the half a gallon

Luck to the barley mow

Jolly good luck to the half a gallon

Good luck to the barley mow

Oh the half a gallon, quart pot, pint pot, half pint, gill pot, half gill, quarter gill

Fetch in a little drop more

Here’s good luck, good luck, to the barley mow.

… the gallon

… the half a bushel

… the bushel

… the half a barrel

… the barrel

… the barmaid

… the landlady

… the landlord

… the brewery

… all this company

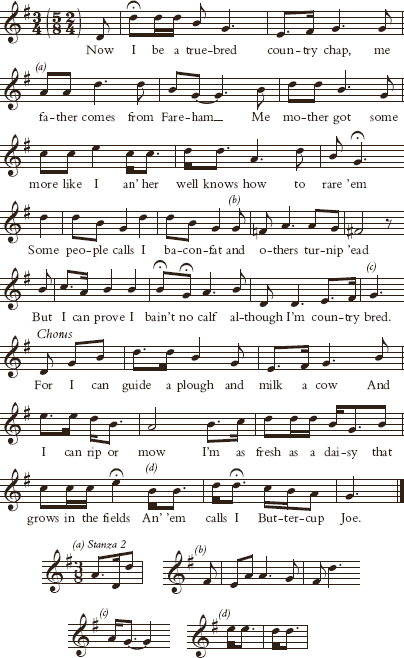

93

Buttercup Joe

Now I be a true-bred country chap, me father comes from Fareham

Me mother got some more like I an’ her well knows how to rare [rear] ’em

Some people calls I bacon-fat and others turnip ’ead

But I can prove I bain’t no calf although I’m country bred.

Chorus

For I can guide a plough and milk a cow

And I can rip or mow

I’m as fresh as a daisy that grows in the fields

An’ ’em calls I Buttercup Joe.

Now have you seen my young ’ooman, ’em calls her our Mary

Her works as busy as a bumblebee down in Sir Johns’s dairy

And don’t her make some dumplings nice, by joves I means to try ’em

An’ ax her how her’d like to wed a country chap like I am.

Some folk they do like haymaking, there’s others they likes mowin’

But of all the jobs that I loves best, then give I turnip hoein’

And don’t I hopes when I gets wed to my old Mary Ann

I’ll work for her and try me best, to please her all I can.

94

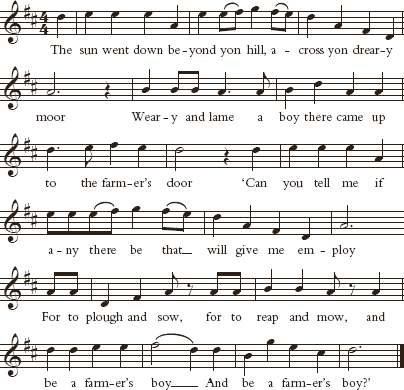

The Farmer’s Boy

The sun went down beyond yon hill, across yon dreary moor

Weary and lame a boy there came up to the farmer’s door

‘Can you tell me if any there be that will give me employ

For to plough and sow, for to reap and mow, and be a farmer’s boy

And be a farmer’s boy?’

‘My father’s dead and my mother’s left with her five children small

And what is worse for my mother still, I’m the oldest of them all

Though little I am I fear no work, if you’ll give me employ

For to plough and sow, for to reap and mow, and be a farmer’s boy

And be a farmer’s boy.’

‘And if that you won’t me employ, one favour I’ve to ask

Will you shelter me till the break of day from this cold winter’s blast?

At the break of day I’ll trudge away, elsewhere to seek employ

For to plough and sow, for to reap and mow, and be a farmer’s boy

And be a farmer’s boy.’

The farmer said, ‘I’ll try the lad, no further let him seek.’

‘Oh yes, dear father,’ the daughter said, while tears ran down her cheek

‘For them that will work it’s hard to want and wander for employ

For to plough and sow, for to reap and mow, and be a farmer’s boy

And be a farmer’s boy.’

At length the boy became a man, the good old farmer died

He left the lad the farm he had and his daughter to be his bride

And now that lad a farmer is, and he smiles and thinks with joy

Of the lucky, lucky day he came that way, to be a farmer’s boy

To be a farmer’s boy.

95

Fathom the Bowl

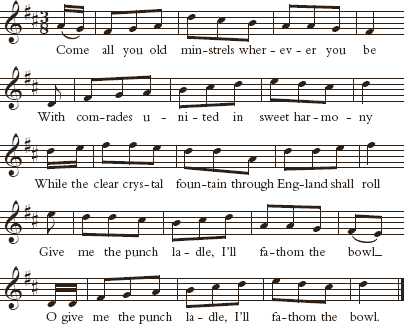

Come all you old minstrels wherever you be

With comrades united in sweet harmony

While the clear crystal fountain through England shall roll

Give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl

O give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl.

Let nothing but harmony reign in our breast

Let comrade with comrade be ever at rest

[Let’s lift up our glasses, good cheer is our goal]

Give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl

O give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl.

From France cometh brandy, Jamaica gives rum

Sweet oranges, lemons from Portugal come

Of beer and good cider we’ll also take toll

Give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl

O give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl.

Our brothers lie drowned in the depths of the sea

Cold stones for their pillows, what matters to we?

We’ll drink to their healths and repose to each soul

Give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl

O give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl.

Our wives they may bluster as much as they please

Let ’em scold, let ’em grumble, we’ll sit at our ease

[They may scold and grumble till they’re black as the coal]

Give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl

O give me the punch ladle, I’ll fathom the bowl.

96

Green Brooms

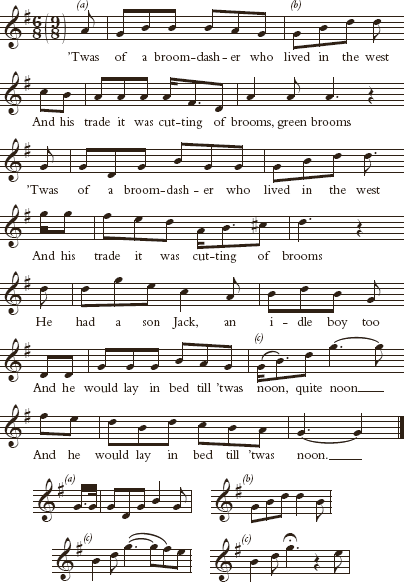

’Twas of a broomdasher who lived in the west

And his trade it was cutting of brooms, green brooms

’Twas of a broomdasher who lived in the west

And his trade it was cutting of brooms

He had a son Jack, an idle boy too

And he would lay in bed till ’twas noon, quite noon

And he would lay in bed till ’twas noon.

So the old man he rose and downstairs he goes

And he swore he would fire Jack’s room, room room

The old man he rose and downstairs he goes

And he swore he would fire Jack’s room

If he didn’t arise and sharp up his knives

And go to the wood and cut brooms, green brooms

And go to the wood and cut brooms.

So Jack he arose and he put on his clothes

And he went to the wood to cut brooms, green brooms

So Jack he arose and put on his clothes

And he went to the wood to cut brooms

He vowed and he swore he’d do it no more

That he’d go to the wood to cut brooms, green brooms

He’d go to the wood and cut brooms.

So Jack trudg-ed on to where he’s not known

Till he came to a castle of fame, fame fame

So Jack trudg-ed on to where he’s not known

Till he came to a castle of fame

And there he did bawl as loud as could call

‘Kind lady, do you want any brooms, green brooms?

Kind lady, do you want any brooms?’

The lady was there, and hearing Jack bawl

Said, ‘Call the young man with his brooms, brooms brooms.’

The lady was there, and hearing Jack bawl

Said, ‘Call the young man with his brooms.’

So Jack trudg-ed on to where he’s not known

Till he came to the lady’s fair room, room room

Till he came to the lady’s fair room.

She said, ‘You young blade, why not leave off your trade

And marry a lady in bloom, full bloom.’

She said, ‘You young blade, why not leave off your trade

And marry a lady in bloom.’

So Jack gave his consent and to the church went

And he married the lady in bloom, full bloom

And he’s married that lady in full bloom.

97

John Barleycorn

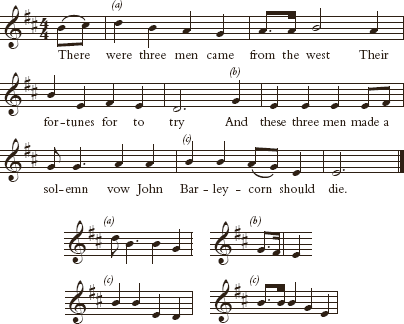

There were three men came from the west

Their fortunes for to try

And these three men made a solemn vow

John Barleycorn should die.

So they ploughed and sowed and harrowed him in

Throwed clats upon his head

And these three men made a solemn vow

John Barleycorn was dead.

Then they let him lay for a long time

Till rain from heaven did fall

And little Sir John sprang up his head

And he amazed them all.

Then they let him stand for a long time

And he grew both pale and wan

And little Sir John grew with a long beard

And so he became a man.

They hired men with scythes so sharp

To cut him off at the knee

And the loader he served him worse than that

For he served him most barbarously.

Then they dragged him round and round the field

Till they came unto a barn

And there they made a solemn mow

Of poor John Barleycorn.

They hired men with crab-tree sticks

They cut him skin from bone

And the miller he served him worse than that

For he ground him between two stones.

Now here’s little Sir John in a nut-brown bowl

And brandy in a glass

And here’s little Sir John in a nut-brown bowl

He’ll slay the strongest man at last.

For the huntsman he can’t hunt the fox

Nor loudly blow his horn

Nor the tinker he can’t mend kettles or pots

Without little Lord Barleycorn.

98

The Jolly Waggoner

When first I went a-waggoning, a-waggoning did go

I broke my parents’ hearts with sorrow, grief and woe

For many were the hardships that we had to undergo

Singing whoa, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on

For there’s none can drive a waggon when the horses will not go.

On a cold and frosty morning I was wet through to my skin

And there we had to wander till we reached to yonder inn

There we sat a-talking to the landlord and his wife

Singing whoa, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on

For there’s none can drive a waggon when the horses will not go.

O the summertime is coming, what pleasures shall I see

The blackbird and the throstle sing in every greenwood tree

And every lass shall have a lad and sit her on his knee

Singing whoa, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on, my lads, drive on

For there’s none can drive a waggon when the horses will not go.

99

The Lark in the Morning

The lark in the morning she rises from her nest

She mounts into the air with the dew on her breast

’Twas down in yonder meadow I carelessly did stray

Oh there’s no one like the ploughboy in the merry month of May.

When his day’s work is over and then what will he do

He’ll fly into the country, his wake to go

And with his pretty sweetheart he’ll whistle and he’ll sing

And at night he’ll return to his own home again.

And when he returns from his wake unto the town

The meadows they are mowed and the grass it is cut down

The nightingale she whistles upon the hawthorn spray

And the moon is a-shining upon the new-mown hay.

So here’s luck to the ploughboys wherever they may be

They’ll take a winsome lass to sit on their knee

And with a jug of beer, boys, they’ll whistle and they’ll sing

For the ploughboy is as happy as a prince or a king.

100

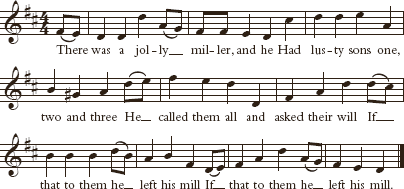

The Miller’s Three Sons

There was a jolly miller and he

Had lusty sons one, two and three

He called them all and asked their will

If that to them he left his mill

If that to them he left his mill.

He called first to his eldest son

Saying, ‘My life is almost run

If I to you this mill do make

What toll do you intend to take

What toll do you intend to take?’

‘Father,’ said he, ‘my name is Jack

Out of a bushel I’ll have a peck

From every bushel that I grind

That I may a good living find

That I may a good living find.’

‘Thou art a fool!’ the old man said

‘Thou has not well learned thy trade

This mill to thee I ne’er will give

For by such toll no man can live

For by such toll no man can live.’

He called for his middlemost son

Saying, ‘My life is almost run

If to you this mill I do make

What toll do you intend to take

What toll do you intend to take?’

‘Father,’ says he, ‘my name is Ralph

Out of a bushel I’ll take a half

From every bushel that I grind

That I may a good living find

That I may a good living find.’

‘Thou art a fool,’ the old man said

‘Thou has not well learned thy trade

The mill to you I ne’er will give

For by such toll no man can live

For by such toll no man can live.’

He called for his youngest son

Saying, ‘My life is almost run

If I to you this mill do make

What toll do you intend to take

What toll do you intend to take?’

‘Father,’ said he, ‘I’m your only boy

For taking toll is all my joy

Before I will a good living lack

I’ll take it all and forswear the sack

I’ll take it all and forswear the sack.’

‘Thou art the boy,’ the old man said

‘For thou hast right well learned thy trade

This mill to thee I give,’ he cried

And then turned up his toes and died

And then turned up his toes and died.

101

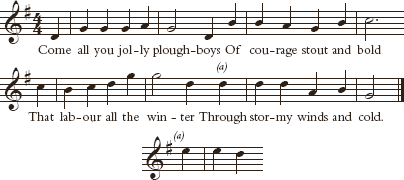

The Painful Plough

Come all you jolly ploughboys

Of courage stout and bold

That labour all the winter

Through stormy winds and cold.

‘Hold, ploughman,’ says the gardener

‘Count not your trade with ours

But walk you through the garden

And view the various flowers.’

‘Likewise those curious borders

And pleasant walks renew

There’s no such piece of pleasure

Performed by the plough.’

‘Hold, gardener,’ says the ploughman

‘No calling I despise

For each man for a living

Upon his trade relies.’

‘For Adam was a ploughman

When ploughing did begin

The next that did succeed him

Was Cain his eldest son.’

‘Some of the generations

The calling to pursue

That bread might not be wanted

For needing of the plough.’

‘For Samson was a strong man

And Solomon was wise

Alexander for the conquering

Was all that he did prize.’

‘King David he was valiant

And many a man he slew

But none of these bold heroes

Can live without the plough.’

‘Now all these wealthy merchants

Will plough the raging seas

That bring home foreign treasures

For those that live at ease.’

‘And fine silks from the Indies

With flour and spices too

They all are brought to England

By virtue of the plough.’

I hope none are offended

At me for singing this

It never was intended

For to be taken amiss.

If it were not for the ploughboys

Both rich and poor might rue

For we are all depending

Upon the painful plough.

102

Twankydillo

Here’s a health to the jolly blacksmith, the best of all fellows

The man at his anvil while the boy blows the bellows

For it makes our bright hammer to rise and to fall

There’s the old Cole and the young Cole and the old Cole of all

Twankydillo, Twankydillo, dillo, dillo, dillo, dillo, dillo

And a roaring pair of bagpipes made of a green willow.

Here’s a health to that pretty girl, the one I love best

For she carries the fire within her own breast

For it makes my bright hammer to rise and to fall

There’s the old Cole and the young Cole and the old Cole of all

Twankydillo, etc.

If a gentleman calls, his horse for to shoe

We make no deliance in one pot or two

For it makes our bright hammers to rise and to fall

There’s the old Cole and the young Cole and the old Cole of all

Twankydillo, etc.

Here’s a health to our queen, likewise all her men

And all the Royal Family that ever was seen

For it makes our bright hammers to rise and to fall

There’s the old Cole and the young Cole and the old Cole of all

Twankydillo, etc.