VIII

Cruel Death Has Put an End …

Songs of Death and Destruction

Cruel Death Has Put an End …

Songs of Death and Destruction

After nineteen years’ experience of the patter and paper line in the streets, I find that a foolish nonsensical thing will sell twice as fast as a good moral sentimental one; and, while it lasts, a good murder will cut out the whole of them. It’s the best selling thing of any. I used at one time to patter religious tracts in the street, but I found no encouragement.

So said a broadside seller to Henry Mayhew in the late 1840s (Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor (1861) I, p. 235).

People of all ages have probably always loved a ‘good murder’, but from the mid eighteenth to the late nineteenth centuries a veritable ‘murder industry’ developed which was fuelled by social changes such as the expansion of transport networks and the availability of cheap printed materials. Not only did thousands flock to see the regular public hangings (abolished in 1868), which were enjoyed as great family outings, but they also visited crime scenes and other associated places where there was always an owner or a neighbour willing to show the very room, and point out the bloodstains. For a really well-known crime, such as the murder of Maria Marten at the Red Barn, you could even buy souvenir ceramic models of the building and the key players to display on your mantlepiece.

Everyone followed the course of particular cases in newspapers and on broadsides, which reported each crime in minute detail, but both the legitimate press and street hacks were quite happy to include spurious details based on rumour and prejudice, and it is often difficult for modern researchers to sort out fact from fiction. Melodramas, puppet shows, peep shows, waxworks, print-sellers and countless other manifestations of popular culture quickly followed and cashed in on the latest sensation, keeping it in the public eye for a considerable time after the real perpetrator met his or her fate. The broadsides and the stage shows often included songs written for the occasion.

But despite wide dissemination, few of the songs written about real murders seem to have lasted in singers’ repertoires (‘Maria Marten’, No. 123, is an exception), and traditional singers seem to have preferred the generic fictional cases, of which the ‘murdered sweetheart’ songs are an important subcategory. ‘The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter’ (No. 117), ‘Mary in the Silvery Tide’ (No. 125) and ‘The Oxford Girl’ (No. 129) are examples included here, but there were many others.

Child ballads also include more than their fair share of violence, and ‘The Cruel Mother’ (No. 116), ‘Hugh of Lincoln’ (No. 119) and ‘The Outlandish Knight’ (No. 127) each focuses on a different variety of human mortality, but for pure Gothic horror in song, nothing beats ‘Lambkin’ (No. 121).

Not all deaths in folk song were murders, of course. Many songs focused on shipwrecks and other disasters, executions or personal accidents (‘The Lakes of Cold Finn’, No. 120, and ‘The Mistletoe Bough’, No. 126), or used unexplained deaths as an element in a tragic love story (‘The Trees They Do Grow High, Part III, No. 55; ‘Lord Lovel’, No. 122; and ‘The Unquiet Grave’, No. 130).

115

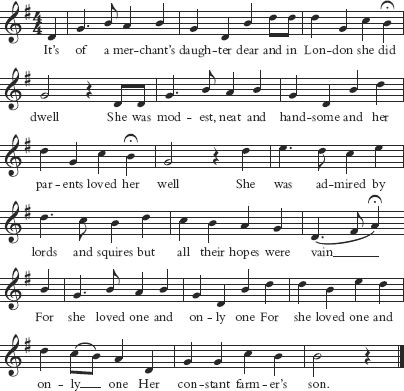

The Constant Farmer’s Son

It’s of a merchant’s daughter dear and in London she did dwell

She was modest, neat and handsome and her parents loved her well

She was admired by lords and squires but all their hopes were in vain

For she loved one and only one

For she loved one and only one

Her constant farmer’s son.

Her parents they consented, but her brothers they said nay

So they asked young William’s company with them to spend the day

But mark, returning home again, how soon his race was run

For with a stake the life did take

For with a stake the life did take

Of her constant farmer’s son.

As Mary on her pillow lay she had a dreadful dream

She dreamt she saw his body laid down by some crystal stream

Then she arose, put on her clothes, to seek her love did go

It’s dead and cold she did behold

It’s dead and cold she did behold

Her constant farmer’s son.

With those cold tears all on his cheeks and mingled with his gore

She strived in pain to ease her pain, she kissed him ten times o’er

She gathered the green leaves from the trees to keep him from the sun

A night and day she passed away

A night and day she passed away

With her constant farmer’s son.

Now hunger came creeping o’er the poor girl and homeward she did go

[To try to find his murderers she straightway home did go]

Saying, ‘Parents dear, you soon shall hear, what a dreadful deed was done

In yonder vale lies dead and pale

In yonder vale lies dead and pale

My constant farmer’s son.’

Up spoke the younger brother and he said, ‘It was not I.’

The same replied the elder one, and he swore most bitterly

Young Mary said, ‘Don’t turn red, nor try the law to shun

You have done the deed and you shall bleed

You have done the deed and you shall bleed

For my constant farmer’s son.’

116

The Cruel Mother

There was a lady that lived in York

All alone and a loney O

She proved with child by her own father’s clerk

Down by a greenwood sidey O.

As she was walking down her father’s lawn, etc.

She thought three times that her back would be broke, etc.

As she was walking down her father’s lawn, etc.

She says, ‘Honourable Mary, pity me’, etc.

As she was walking down her father’s lawn, etc.

Where her fine sons they were born, etc.

She pulled out her long penknife, etc.

And there she took away their three lives, etc.

Years went by and one summer’s morn, etc.

She saw three boys they were playing bat and ball, etc.

‘O my fine boys, if you were mine’, etc.

‘Sure I’d dress you up in silk so fine’, etc.

‘O mother dear, when we were yours’, etc.

‘You did not dress us in silk so fine’, etc.

‘You pulled out your long penknife’, etc.

‘And there you took away our three lives’, etc.

‘O my fine boys, what will become of me?’, etc.

‘You’ll be seven long years a bird in a tree’, etc.

‘You’ll be seven long years a tongue in a bell’, etc.

And you’ll be seven long years a porter in hell’, etc.

117

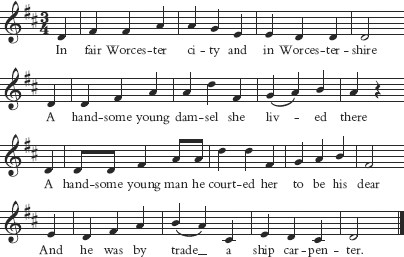

The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter

In fair Worcester city and in Worcestershire

A handsome young damsel she liv-ed there

A handsome young man he courted her to be his dear

And he was by trade a ship carpenter.

Now the King wanted seamen to go on the sea

That caused this poor damsel to sigh and to say

‘O William, O William, don’t you go to sea

Remember the vows that you made to me.’

It was early next morning before it was day

He went to his Polly, these words he did say

‘O Polly, O Polly, you must go with me

Before we are married my friends for to see.’

He led her through groves and valleys so deep

And caused this young damsel to sigh and to weep

‘O William, O William, you have led me astray

On purpose my innocent life to betray.’

‘It’s true, it’s true,’ these words he did say

‘For all the long night I’ve been digging your grave’

The grave being open, the spade standing by

Which caused this young damsel to sigh and to cry.

‘O William, O William, O pardon my life

I never will covet to be your wife

I will travel the world over to set you quite free

O pardon, O pardon, my baby and me.’

‘No pardon I’ll give, there’s no time for to stand’

So with that he had a knife in his hand

He stabbed her heart till the blood it did flow

Then into the grave her fair body did throw.

He covered her up so safe and secure

Thinking no one would find her he was sure

Then he went on board to sail the world round

Before that the murder could ever be found.

It was early one morning before it was day

The captain came up, these words he did say

‘There’s a murderer on board, and he it lately has done

Our ship is in mourning and cannot sail on.’

Then up stepped one, ‘Indeed it’s not me.’

Then up stepped another the same he did say

Then up starts young William to stamp and to swear

‘Indeed it’s not me, sir, I vow and declare.’

As he was turning from the captain with speed

He met his Polly, which made his heart bleed

She stript him, she tore him, she tore him in three

Because he had murdered her baby and she.

118

Edwin in the Lowlands Low

Come all you feeling lovers, give ear unto my song

Concerning gold as we are told that leads so many wrong.

Young Emma was a servant maid; her love a sailor bold

He ploughed the main much gold to gain for his love as we are told.

Young Emma she would daily mourn since Edmund first did roam

And seven years have passed away since Edmund left his home.

He went up to young Emma’s house his gold all for to show

What he had gained all on the main and down in the lowlands low.

‘Oh my father keeps a public inn that stands down by the sea

And go you there, young Edmund, and there this night shall be.’

‘I will meet you in the morning, love, don’t let my parents know

That your name it is young Edmund who ploughs the lowlands low.’

As young Edmund he sat drinking until time to go to bed

But little was he thinking what sorrows crowned his head.

As soon as he had got to bed and scarcely got to sleep

When Emma’s cruel father into his bedroom creep.

He robb-ed him, he stabb-ed him, until the blood did flow

And he sent his body a-rolling down in the lowlands low.

As young Emma she lay sleeping, she dreamt a dreadful dream

She dreamt she saw her own true love and the blood appeared in streams.

Young Emma got up at daybreak, down to her home did go

Because she loved him dearly, who ploughed the lowlands low.

‘Oh father, dearest father, now tell me, I entreat

Oh where is that young man who came last night to sleep?’

‘Oh Emma, dearest Emma, his gold will make a show

And I’ve sent his body a-rolling down in the lowlands low.’

‘Oh father, cruel father, you shall die a public show

For murdering of my own true love, who ploughed the lowlands low.’

‘Now the shells all in the ocean shall make my true love’s bed

And the fish that swim all in the sea shall swim around his head.’

Faint, sick and broken-hearted to bed the maid did go

And her shrieks were of young Edmund who ploughed the lowlands low

[spoken] Lowlands low.

119

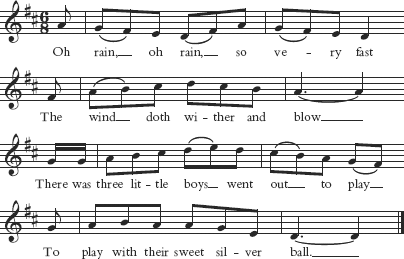

Hugh of Lincoln

Oh rain, oh rain, so very fast

The wind doth wither and blow

There was three little boys went out to play

To play with their sweet silver ball.

They tossed him high, they tossed him low

They tossed him over into the Jew’s garden

The very first of them that did come out

The Jewess, was dressed in green.

‘Come in, come in, you little Sir Hugh

Come in and fetch your ball.’

‘I can’t come in, nor I won’t come in

Without my playmates all.’

At first she showed me an apple so red

And next was a diamond ring

Next was the cherry so red as blood

And so she got me in.

She set me into a silver chair

And fed me with sugar so sweet

She laid me on the dressing board

And stuck me like a sheep.

She throwed me into a new-dug well

It was forty cubits deep

She wropped me up in a red mantle

Instead of a milk-white sheet.

’Twas up and down the garden there

This little boy’s mammie did run

She had a little rod all under her apron

To beat her little son home.

‘Oh here I am, dear mother,’ he cried

‘My grave is dug so deep

The pen-knife sticks so close to my heart

So ’long with you I can’t sleep.’

120

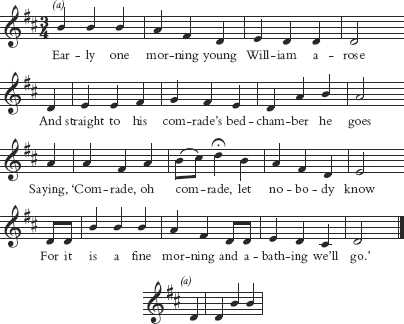

The Lakes of Cold Finn

Early one morning young William arose

And straight to his comrade’s bedchamber he goes

Saying, ‘Comrade, oh comrade, let nobody know

For it is a fine morning and a-bathing we’ll go.’

Young William tripped off till he came to Long Lane

The first that he met was a keeper of game

He advised him for sorrow to turn back again

For the lakes of cold water is the lakes of Cold Finn.

Young William stripped off and he swum the lake round

He swum round the island but not to right ground

Saying, ‘Comrade, oh comrade, don’t you venture in

For the depths of cold water are the lakes of Cold Finn.’

Early that morning his sister arose

And straight to her mother’s bedchamber she goes

Saying, ‘Mother, oh mother, I had a sad dream

That young William was floating on the watery stream.’

Early that morning his mother went there

She’d rings on her fingers and was tearing her hair

Saying, ‘Where was he drownded, or did he fall in?

For the depths of cold water is the lakes of Cold Finn.’

The day of his funeral there shall be a grand sight

Four and twenty young men all dressed up in white

They shall carry him along and lay him on clay

Saying, ‘Adieu to young William’, they’ll all march away.

121

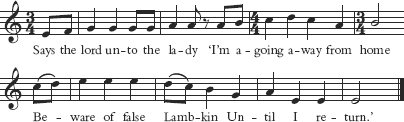

Lambkin

Says the lord unto the lady

‘I’m a-going away from home

Beware of false Lambkin

Until I return.’

‘What cares I for Lambkin

Or any of his kin?

While the doors they are fastened

And darkened within.’

As soon as my lordy

He was got out of sight

Then ready was that cruel Lambkin

To visit her that night.

He rapp-ed at the door

Says, ‘Nurse, let me in

I’ll make you a lady

And visit you in.’

He pinched that poor baby

For to make that for to cry

While Nurse sat a-singing

‘Hush! hush-a by bye.’

So they pinched that poor baby

For to make that for to cry

While Nurse sat a-singing

Hush! hush-a by bye.

‘I cannot keep it good, ma’am

With milk or with pap

So I pray you, kind lady

Come and nurse it in your lap.’

‘How can I come down, nurse

At this time of the night

When there’s no fire a-burning

Nor candle give light?’

‘Put on your golden mantle

That will give you light

And I pray you, kind lady

Come and nurse it your lap tonight.’

She put on her golden mantle

Not thinking any harm

And Lambkin was ready

To catch her in his arms.

‘Brother Lambkin, Brother Lambkin

Spare my life till ten o’clock

I’ll give you as many guineas

As you can carry in your sack.’

‘I want none of your guineas, love

I want none of your gold

For I want to see your heart’s blood

Come trinkling quite cold.’

‘Brother Lambkin, Brother Lambkin

Spare my life till ten o’clock

You shall have my daughter Betsy

As is up in the top.’

‘You may fetch your daughter Betsy

She may do you some good

She may hold the silver basin

For to catch your heart’s blood.’

There’s blood in the kitchen

And there’s blood in the hall

And there’s blood in the parlour

Where the lady did fall.

As Betsy was a-looking

Out of the tower so high

She saw her worried father

A-coming riding by.

‘Worried father! Worried father

Don’t lay the blame on me

It was that cruel Lambkin

That murdered lady and baby.’

And Lambkin is a-hanging

On the high gallows tree

And the nurse is a-burning

In the fire close by.

Oh the death bell is a-knelling

For lady and baby

And the green grass is a-growing

All over they

And the green grass is a-growing

All over they.

122

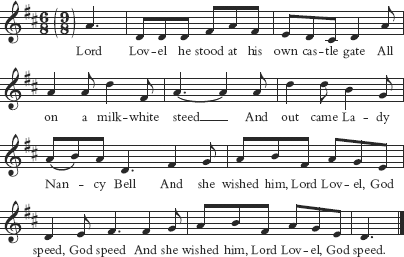

Lord Lovel

Lord Lovel he stood at his own castle gate

All on a milk-white steed

And out came Lady Nancy Bell

And she wished him, Lord Lovel, God speed, God speed

And she wished him, Lord Lovel, God speed.

‘Oh where are you going, Lord Lovel?’ she cried

‘Oh where are you going?’ cried she

‘I’m going, sweet Lady Nancy Bell

Strange countries for to see, to see

Strange countries for to see.’

‘When will you come back, Lord Lovel?’ she cried

‘When will you come back?’ cried she

‘In a year or two, or three at the most

And I’ll return to my Lady Nancy, Nancy

I’ll return to my Lady Nancy.’

He hadn’t been gone but a year and one day

Strange countries for to see

When all at once came into his mind

I’ll return to my Lady Nancy, Nancy

I’ll return to my Lady Nancy.

He mounted on his milk-white steed

And rode to London town

And there he saw a funeral

And the people were weeping around, around

And the people were weeping around.

123

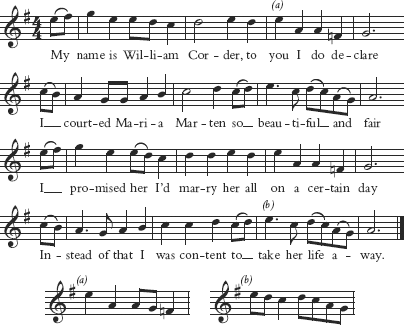

Maria Marten

My name is William Corder, to you I do declare

I courted Maria Marten so beautiful and fair

I promised her I’d marry her all on a certain day

Instead of that I was content to take her life away.

I went unto her father’s house on the eighteenth day of May

He said, ‘I’ve come, my dearest Maria, we’ll fix the wedding day

If you’ll meet me at the Red Barn floor as sure as you’re alive

I’ll take you down to Ipswich Town and make you my dear bride.’

He straight went home and fetched his gun, his pickaxe and his spade

He went unto the Red Barn floor and he dug poor Maria’s grave

This poor girl she thought no harm but to meet him she did go

She went into the Red Barn floor and he laid her body low.

Her mother dreamt three dreams one night, she ne’er could get no rest

She dreamed she saw her daughter dear lay bleeding at the breast

Her father went into the barn and up the boards he took

There he saw his daughter dear lay mingled in the dust.

Now all young men do you beware, take a pity look on me

For the time is past to die at last all on the gallus tree.

124

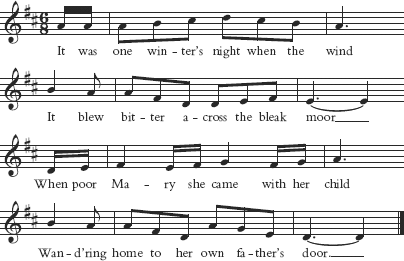

Mary Across the Wild Moor

It was one winter’s night when the wind

It blew bitter across the bleak moor

When poor Mary she came with her child

Wand’ring home to her own father’s door.

She cried, ‘Father, O pray let me in

Do come down and open your own door

Or the child at my bosom will die

With the wind that blows on the wild moor.’

‘Why ever did I leave this cot

Where once I was happy and free

Doomed to roam without friend or home

O father, have pity on me.’

But her father was deaf to her cry

Not a voice nor a sound reached the door

But the watch dog’s bark and the wind

That blew bitter across the wild moor.

Now think what her father he felt

When he came to the door in the morn

And found Mary dead, and her child

Fondly clasped in its dead mother’s arms.

Wild and frantic he tore his grey hairs

As on Mary he gazed at the door

Who on the cold night there had died

By the wind that blew on the wild moor.

Now her father in grief pined away

The poor child to its mother went soon

And no one lived there to this day

And the cottage to ruin has gone.

The villagers point to the spot

Where the willow droops over the door

They cry out there poor Mary died

With the wind that blew o’er the wild moor.

125

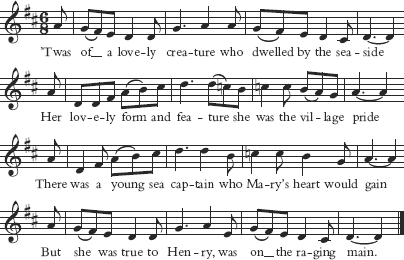

Mary in the Silvery Tide

’Twas of a lovely creature who dwelled by the seaside

Her lovely form and feature she was the village pride

There was a young sea captain who Mary’s heart would gain

But she was true to Henry, was on the raging main.

’Twas in young Henry’s absence this nobleman he came

A-courting pretty Mary, but she refused the same

She said, ‘I pray you begone, young man, your vows are all in vain

Therefore begone, I love but one, he’s on the raging main.’

With mad desperation this nobleman he said

‘To prove the separation I’ll take her life away

I’ll watch her late and early and then alone,’ he cried

‘I’ll send her body a-floating in the rippling silvery tide.’

This nobleman was walking out to take the air

Down by the rolling ocean he met the lady fair

He said, ‘My pretty fair maid, you consent to be my bride

Or you shall swim far, far from here in the rolling silvery tide.’

With trembling limbs cried Mary, ‘My vows I never can break

For Henry I dearly love and I’ll die for his sweet sake.’

With his handkerchief he bound her hands and plunged her in the main

And shrinking her body went floating in the rolling silvery tide.

It happened Mary’s true love soon after came from sea

Expecting to be happy and fixed the wedding day

‘We fear your true love’s murdered,’ her aged parents cried

‘Or she caused her own destruction in the rolling silvery tide.’

As Henry on his pillow lay he could not take no rest

For the thoughts of pretty Mary disturbed his wounded breast

He dreamed that he was walking down by a riverside

He saw his true love weeping in the rolling silvery tide.

Young Henry rose at midnight, at midnight gloom went he

To search the sandbanks over down by the raging sea

At daybreak in the morning poor Mary’s corpse he spied

As to and fro she was floating in the rolling silvery tide.

He knew it was his Mary by the ring on her hand

He untied the silk handkerchief which put him to a stand

For the name of her cruel murderer was full thereon he spied

Which proved who ended Mary’s days in the rolling silvery tide.

This nobleman was taken, the gallus was his doom

For ending pretty Mary’s days, she had scarce attained her bloom

Young Henry broken-hearted he wandered till he died

His last words was for Mary in the rolling silvery tide.

126

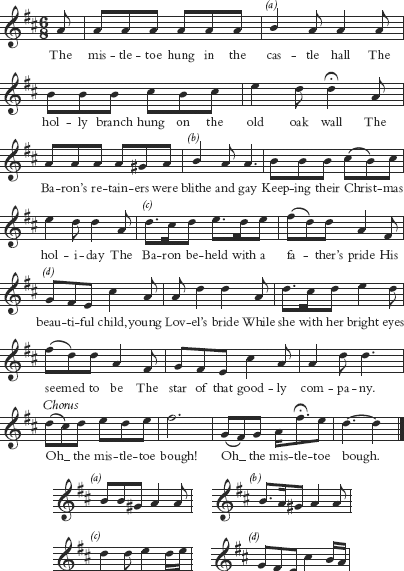

The Mistletoe Bough

The mistletoe hung in the castle hall

The holly branch hung on the old oak wall

The Baron’s retainers were blithe and gay

Keeping their Christmas holiday

The Baron beheld with a father’s pride

His beautiful child, young Lovel’s bride

While she with her bright eyes seemed to be

The star of that goodly company.

Chorus

Oh the mistletoe bough!

Oh the mistletoe bough.

‘I’m weary of dancing now,’ she cried

‘Here tarry a moment, I’ll hide, I’ll hide

And Lovel be sure thou’rt the first to trace

The clue to my secret hiding place.’

Away she ran and her friends began

Each tower to search and each nook to scan

And young Lovel cried, ‘Oh where dost thou hide?

I’m lonesome without thee, my own dear bride.’

They sought her that night, they sought her next day

They sought her in vain till a week passed away

In the highest and the lowest and the loneliest spot

Young Lovel sought wildly but found her not

And years flew by and their grief at last

Was told as a sorrowful tale long past

When Lovel appeared the children cried

‘See the old man weeps for his fairy bride.’

At length an old chest that had long lain hid

Was found in the castle, they raised the lid

A skeleton form lay mouldering there

In the bridal wreath of a lady fair

Oh sad was her fate in sporting jest

She hid from her lord in the old oak chest

It closed with a spring and her bridal bloom

Lay withering there in the living tomb.

127

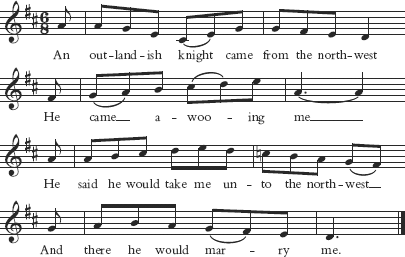

The Outlandish Knight

An outlandish knight came from the north-west

He came a-wooing me

He said he would take me unto the north-west

And there he would marry me.

‘Go fetch me some of your father’s gold

And some of your mother’s fee

And two of the best nags out of the stable

Where there stand thirty and three.’

She fetched him some of her father’s gold

And some of her mother’s fee

And two of the very best nags out of the stable

Where there stood thirty and three.

She mounted on her lily-white steed

He on the dapple grey

They rode until they came to the seaside

Three hours before it was day.

‘Mount off, mount off, thy lily-white steed

And deliver it unto me

For six pretty maidens I have drowned here

And the seventh thou shalt be.’

‘Take off, take off thy silken dress

And deliver it unto me

For I think it looks too rich by far

To rot all in the salt sea.’

‘If I must take off my silken dress

Pray turn your back to me

For it is not fitting that such a ruffian

A naked woman should see.’

He turned his back towards her

And viewed the lakes so green

She caught him round the middle so small

And bundled him into the sea.

He growped high and he growped low

Until he came to the side

‘Take hold o’ my hand, my pretty lady

And I will make you my bride.’

‘Lie there, lie there, you false-hearted man

Lie there instead of me

For if six pretty maids thou hast drowned here

The seventh hath drowned thee.’

She mounted on her lily-white steed

And led the dapple grey

She rode till she came to her own father’s door

Three hours before it was day.

The parrot being up in the window so high

And seeing the lady did say

‘I fear that some ruffian hath led you astray

That you’ve tarried so long away.’

‘Don’t prittle nor prattle, my pretty Polly

Nor tell no tales of me

Your cage shall be made of some glittering gold

Although it is made of a tree.’

The King being up in his chamber so high

And hearing the parrot did say

‘What ails you, what ails you, my pretty Polly

That you prattle so long before day?’

‘It’s no laughing matter,’ the parrot replied

‘That so loudly I called unto thee

For the cats have got into the window so high

And I’m afraid they will have me.’

‘Well turned, well turned, my pretty Polly

Well turned, well turned, for me

Thy cage shall be made of some glittering gold

And the door of the best ivory.’

128

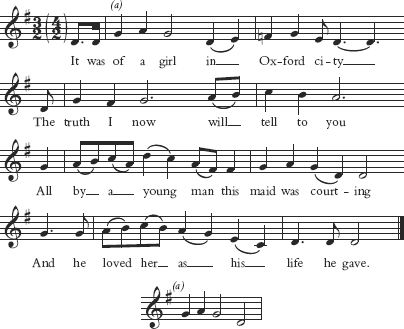

Oxford City

It was of a girl in Oxford city

The truth I now will tell to you

All by a young man this maid was courting

And he loved her as his life he gave.

She loved him too, but ’twas at a distance

She did not seem to be so fond

He said, ‘My dear one, why can’t we marry?

And then at once it would end all strife.’

‘Oh no, I am too young to marry

Too young to incline on a marriage bed

For when we are married then we are bound for ever

And then at once all our joys are fled.’

As she was dancing with some other

This jealousy came to his mind

All for to destroy his own true loved one

This wicked young man he was inclined.

Some poison strong which he had conceal-ed

He mixed it in a glass of wine

Then he gave it unto his own true loved one

And she drank it up most cheerfully.

But in a very few minutes after

‘Oh take me home, my dear,’ said she

‘For the glass of liquor you lately gave me

It makes me feel very ill indeed.’

‘Oh I’ve been drinking the same before you

And I’ve been taken as ill as you

So in each other’s arms we will die together’

Young men be aware of such jealousy.

129

The Oxford Girl

As I was fast-bound ’prentice boy, I was bound unto a mill

And I served my master truly for seven years and more

Till I took up a-courting with the girl with the rolling eye

And I promised that girl I’d marry her if she would be my bride.

So I went up to her parents’ house about the hour of eight

But little did her parents think that it should be her fate

I asked her if she’d take a walk through the fields and meadows gay

And there we told the tales of love and fixed the wedding day.

As we were walking and talking of the different things around

I drew a large stick from the hedge and knocked that fair maid down

Down on her bending knees she fell and so loud for mercy cried

‘Oh come spare the life of an innocent girl for I am not fit to die.’

Then I took her by the curly locks and I dragged her on the ground

Until I came to the riverside that flowed through Ekefield town

It ran both long and narrow, it ran both deep and wide

And there I plunged this pretty fair maid that should have been my bride.

So when I went home to my parents’ house about ten o’clock that night

My mother she jumped out of bed all for to light the light

She asked me and she questioned me, ‘Oh what stains your hands and clothes?’

And the answer I gave back to her, ‘I’ve been bleeding at the nose.’

So no rest, no rest, all that long night, no rest, no rest could I find

The fire and the brimstone around my head did shine

It was about two days after this fair young maid was found

A-floating by the riverside that flowed through Ekefield town.

Now the judges and the jurymen on me they did agree

For murdering of this pretty fair maid so hang-ed I shall be

Oh hang-ed, oh hang-ed, oh hang-ed I shall be

For murdering of this pretty fair maid, so hang-ed I shall be.

130

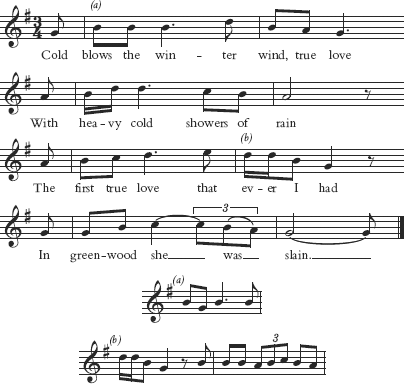

The Unquiet Grave

Cold blows the winter wind, true love

With heavy cold showers of rain

The first true love that ever I had

In greenwood she was slain.

I’ll do as much for my true love

As any young man may

I’ll sit and mourn all on her grave

A twelvemonth and a day.

A twelvemonth and a day being gone

The ghost began to speak

‘Why sit you here all on my grave

And never let me sleep?’

‘What dost thou want of me, true love?

What dost thou want of me?’

‘A kiss from off thy clay-cold lips

That’s all I request of thee.’

‘My lily-white lips are clayey cold

My breath smells earthy strong.’

‘And if I kiss all off your lips

Your time will not be long.’

‘My time be long, my time be short

Tomorrow or today

Sweet Christ in heaven will have my soul

And take my life away.’

‘Don’t grieve, don’t grieve for me, true love

No mourning do I crave

I must leave you and all the world

And sink down in my grave.’