Post-Xenakian Art : After and Beyond Xenakis

Peter Hoffmann (Berlin, Germany)

ABSTRACT

Abstract : 12 years after Xenakis’ death, his ideas are getting even more impact than during his lifetime. This may be due to nowaday’s easy availability of high computer processing power and musical programming systems (like e.g. SuperCollider). They make it much easier to implement and expand upon concepts that Xenakis could only postulate as utopian ideas. In this article, I’d like to present a number of artists who push Xenakis’ heritage further by adding aspects that were unavailable or alien to Xenakis : real-time composition and collaboration, interaction, and the combination of sound and video art.

1. INTRODUCTION

At the Xenakis International Symposium 2011 in London, I presented a handful of artists whom I labeled “Post-Xenakians” [Hoffmann2011b]. “Post” was meant in a double sense : these artists are doing art after Xenakis (both in a temporal and causal sense) but in doing so, they go beyond of what Xenakis was able to realize during his lifetime. I grouped these artists into four categories : UPICists, GENDYNists, Emergencists, and Immersionists. UPIC and GENDYN are both composition tools that Xenakis conceived and used himself. Emergence is a phenomenon explored by Xenakis through study and composition of mass phenomena (i.e. the emergence of a statistical property out of its many constituents). Effects of immersion were achieved by Xenakis through the simultaneity of composed sound, location and/or visuals (like in his famous Polytopes which were multimedia installations or events, cf. [Revault d’Allonnes 1975], [Sterken 2004]).

One year later, at the Xenakis International Symposium 2012 in Paris, I added three more artists. They cover all four categories at the same time : they use UPIC and GENDYN in an emergent manner within immersive situations. These are Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker, with Alberto de Campo providing an adapted GENDYN tool.

For my description of “Post-Xenakian Art”, I only consider electroacoustic music. It is relatively easy to define electroacoustic art as “Post-Xenakian” : either it is made with tools that Xenakis invented and used for his own art, so it could simply not exist without Xenakis having invented them in the first place, or it is made with explicit reference to his work, as testified in program notes, work titles, or articles by the composers. Is seems as if in electroacoustics, composers are more willing to pay tribute to a precursor than in classical composition for instruments. Xenakis himself was a very bad example in this regard. He refused to acknowledge influences by any composer whosoever, due to his self-imposed dogma of “originality”. In contrast, most artists doing electroacoustics today have no problem stating that they have been inspired by Xenakis’ work. There are so many possibilities to do it different than Xenakis – in electroacoustics, art is still being invented.

Xenakis lived too early to see his creative ideas realized to their full potential. He would have been happy to see how a young composer-programmer (he himself was one of the first deserving this title) in our days realizes within a few minutes a musical or conceptual idea that Xenakis himself was not able to realize in years, even with the help of specialists. Think of his vain effort to get Granular Synthesis, a concept he invented, to work with computers. (The young composer-programmer to realize it was Curtis Roads [Roads 1978].) Another example is sieve synthesis. Xenakis dreams it up in his preface to the 1992 Pendragon edition of Formalized Music [Xenakis 1992] but was never able to try it out on a computer. When I challenged my audience with this idea on the 2011 London Xenakis conference, one of the young composer-programmers present (it was Nick Collins [Collins 2012]), showed me three alternate solutions right after the talk (I think he hacked it away while listening). Another example is IanniX [Coduys 2004], an extension of the UPIC paradigm of graphic synthesis to 3d graphics. This system realizes some of Xenakis’ dreams he had for the UPIC but which could not be tried out at CEMAMu. Or think of the Cosmosƒ “Advanced Stochastic Synthesizer” by Sinan Bökesoy [Bökesoy 2013]. In my London talk, I called Sinan the “One-Man-CEMAMu” [Hoffmann 2011b].

2. IANNIS XENAKIS’ TOOLS : UPIC AND GENDYN

The two tools that Xenakis invented and that have later been used by other composers are the graphical synthesizer / sequencer UPIC on the one hand and the stochastic composition program GENDYN on the other.

2.1. UPIC

UPIC means designing electroacoustic compositions by hand, like an architect, on a drawing board. The drawings control the sound synthesis : frequency curves, envelopes, waveforms. UPIC sounds are rather simple and static, but this is compensated by the fact that UPIC invites for designing complex combinations of these sounds.

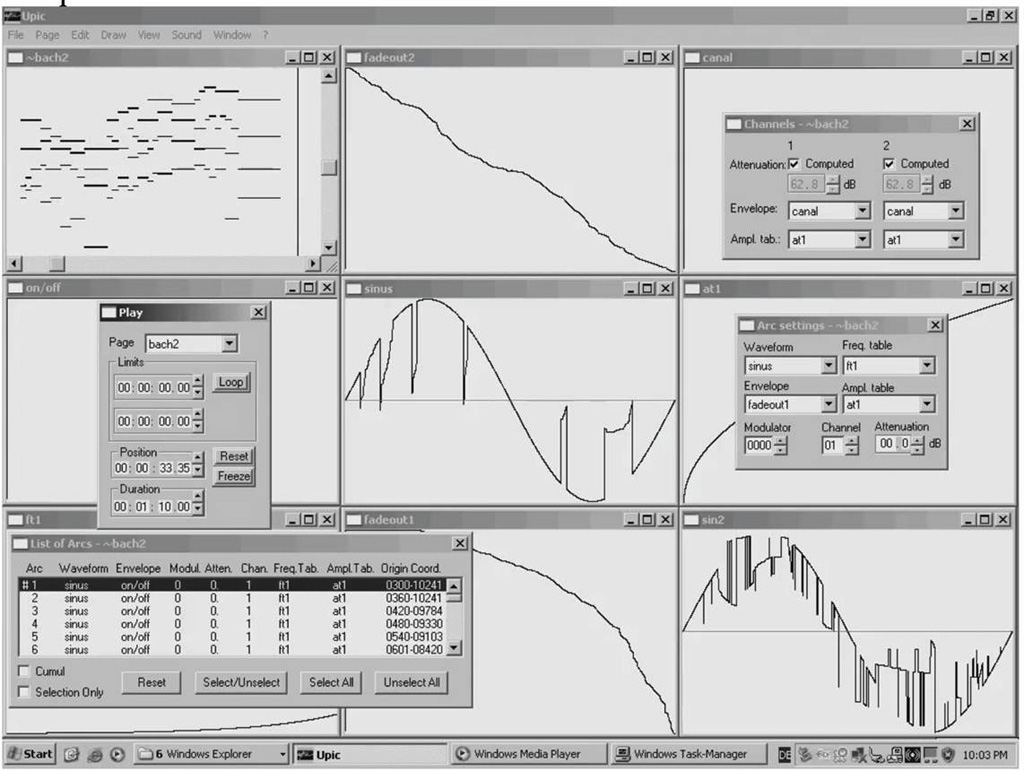

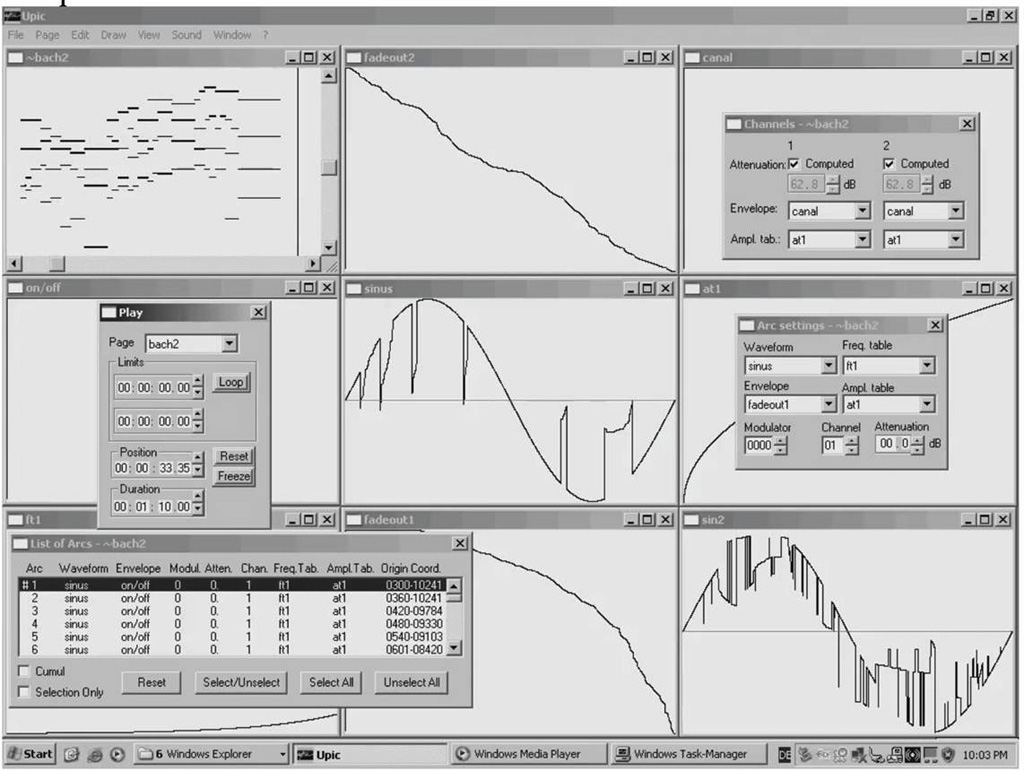

Figure 1. The graphical user interface of the software version of UPIC 3 called upix, in a demo version as of 2001. Loaded is the tutorial example of a Bach chorale “Jesu meine Freude”, delivered with the demo version. Visible are, from top left to bottom right, the score page, showing the piano roll notation of the chorale, a fadeout envelope, stereo settings, an attack envelope with the play dialogue floating on top of it, a jagged sinusoid, a logarithmic dynamic mapping table with the parameters of a selected arc floating on top of it, an exponential frequency mapping table with the list of all score arcs of the piece floating on top of it, an alternate fadeout, and finally an alternate waveform.

The UPIC system was built from Xenakis’ ideas by the engineers of the CEMAMu, his research institute near Paris (1972-2001) [Marino 1993]. Hundreds of composers have used UPIC, first in CEMAMu, then as visiting composers in Les Ateliers UPIC (from 1985), later (2000) rebaptized CCMIX, now (from 2010) CIX. In London, I presented the work of Wilfried Jentzsch (1995), Angelo Bello (1998) and Thierry Coduys (from 2004) [Hoffmann 2011b].

2.2. GENDYN

Xenakis’ invention of Stochastic Sound, his GENDYN program and GENDY3 piece (1991) are unique. Unfortunately, he made only two pieces with GENDYN (the second being S709 from 1994). However, over the years, young composers have added more research and compositions to this idea of creating sound and composition with probabilities. In London, I presented the work of Paul Doornbusch (1998), Jaeho Chang (1999), Alberto de Campo (2001), Andrew R. Brown (2005), Sergio Luque (2006), Luc Döbereiner (2008), Eric Bumstead (2009), and Nick Collins (2010) [Hoffmann 2011b].

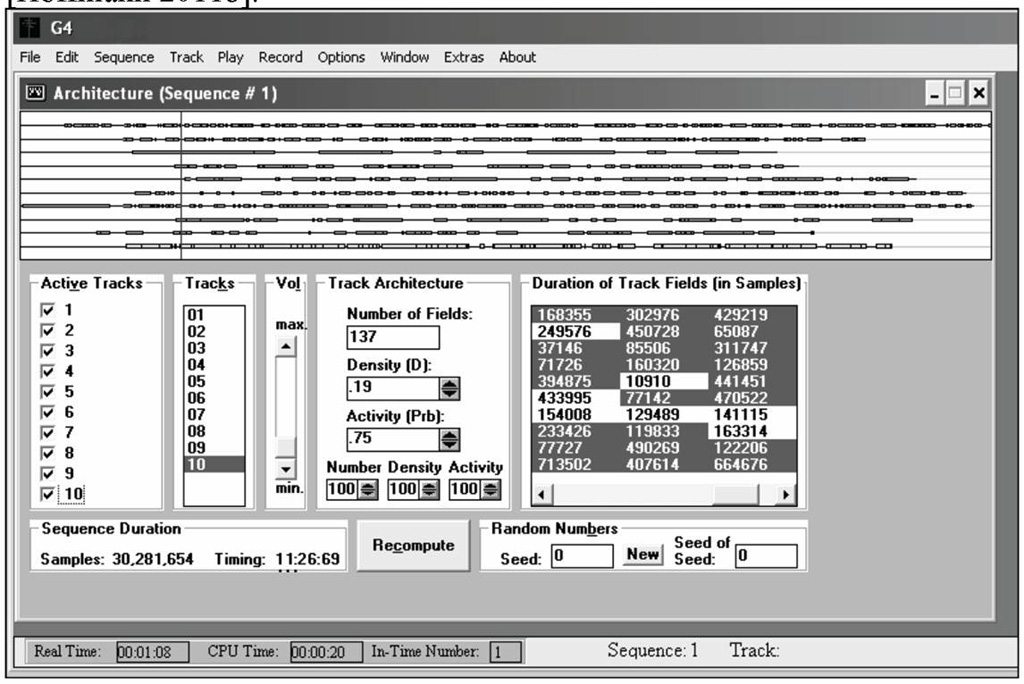

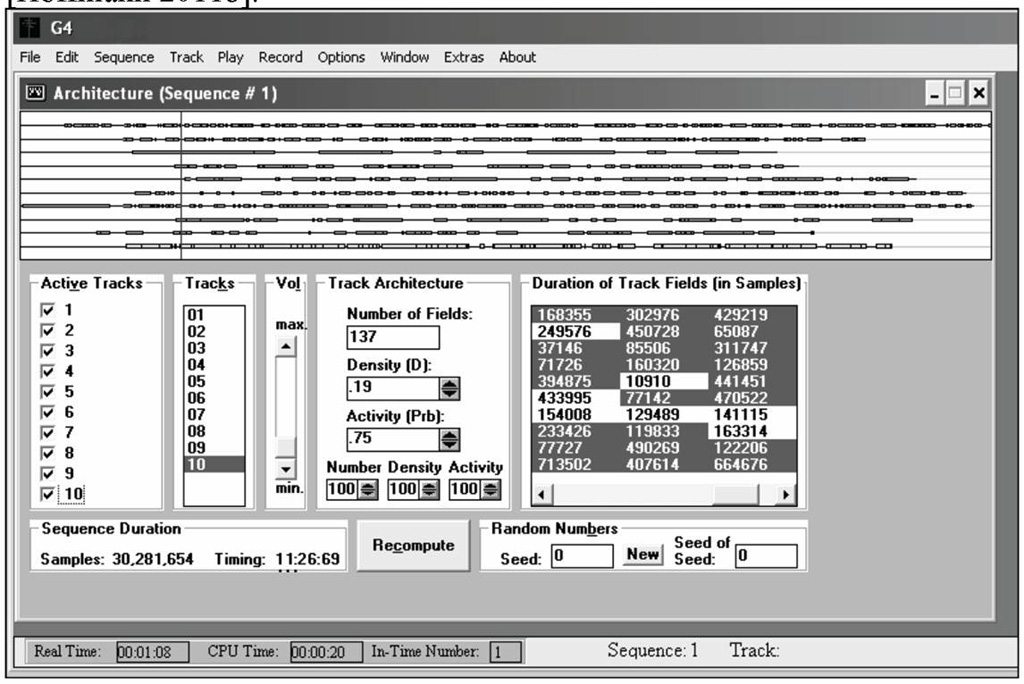

Figure 2. Example of a composition made with the New GENDYN Progam : G4 by Paul Doornbusch (1999). One can see the duration structure („score synthesis“) of the entire piece with its „patches“ of sound distributed over 10 simultaneous „voices“. Note that pitch is not part of score synthesis but an emergent by-product of sound synthesis, which is not shown in this picture. The picture is taken from Paul’s PhD thesis [Doornbusch 2010]

GENDYN is sound generated out of silence by probability fluctuations, like a sonic Big Bang, without human interference. These fluctuations occur within a waveform which is repeated endlessly. Depending on the impact of the fluctuation, there are sounds between stable tones on the one hand and complete chaotic noise on the other. The picture in figure 2 is taken from the New GENDYN Program I made back in 1996 [Hoffmann 2009]. This program allowed me to resynthesize Xenakis’ piece GENDY3 from 1991. It also made possible generating alternate versions of it or creating entirely new pieces (that was what Australian composer Paul Doornbusch did with his G4 piece, in 1999) [Doornbusch 2002].

2.3. Emergence

Xenakis was proud of having invented Stochastic Music (which is composing with probabilities) and Stochastic Sound Synthesis (which is generating sound by means of probability fluctuations, realized in his GENDYN program). He was not aware though, as it seems, that he was also one of the first composer emergencists. Agostino DiScipio discovered this in his article on Xenakis’ Analogique A et B, speaking of “Second Order Sonorities” [DiScipio 1997], that means sound aspects that are not composed as such but emerge as a kind of side effect from the composition of sonic microstructures [DiScipio 2001], [DiScipio 2008]. I for myself was able to show that with GENDYN, musical properties like pitch movement and non- temperated musical scales, not unlike the pitch sieves so dear to Xenakis, emerge as a secondary by-product from the chaotic wave shaping dynamics of Stochastic Sound Synthesis [Hoffmann 2009]. But Agostino DiScipio goes much farer in his concept of Emergent Sound. He constructs musical “ecosystems” which create musical events out of ambient noise, in an autopoietic process, in close interaction with the audience or even a performer who “plays” his ecosystem [DiScipio 2003]. This is an approach much more radical than Xenakis’, who used emergent processes “only” as a means for composition of musical works in the “classical” sense.

The term “emergent” was coined more than 100 years before by philosopher G. H. Lewes, who wrote :

“Every resultant is either a sum or a difference of the co-operant forces ; their sum, when their directions are the same - their difference, when their directions are contrary. Further, every resultant is clearly traceable in its components, because these are homogeneous and commensurable. It is otherwise with emergents, when, instead of adding measurable motion to measurable motion, or things of one kind to other individuals of their kind, there is a co-operation of things of unlike kinds. The emergent is unlike its components insofar as these are incommensurable, and it cannot be reduced to their sum or their difference.” [Lewes 1875]

It seems as if the notion of emergence had even been preconceived as early as in the 4th century B.C. by Aristotle who wrote in his Metaphysics "... the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts ..." [Aristotle Metaphysics]. This describes well the essence of emergence, where the cooperation of a system’s constituents form a phenomenon of new quality on a higher level.

In the case of GENDYN, the constituents are the sample values and their spacings, and the emergent resultant is pitch and its movement. Under certain conditions, pitch moment is not chaotic, as is the random movement of these sample values, but remains stable for some while so the listener can perceive a stable pitch. After a while, this pitch is left for another stable pitch and so on, and the series of these stable pitches form a scale pattern which is also stable and well perceivable by the listener. This perceivable scale pattern, therefore, is an emergent phenomenon of GENDYN sound generation.

2.4. Immersion

The term immersion (literally : to be drowned into another environment, e.g. sea water) is used in Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality is computer simulation of digital worlds, and immersion into these worlds is defined to be the suspension of disbelief in these worlds [Wikipedia Immersion]. In other words, the various visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory or gustatory stimuli stemming from these worlds substitute for the experience of the real physical world. Immersion is the goal of many developments in computer gaming as well as cutting edge industrial design (e.g. the CAVE automatic virtual environment originally developed at the Electronic Visualization Lab at University of Illinois Chicago, from 1992) [EVL 2004].

The term immersion can also be applied to artistic worlds, especially if these stimulate a multitude of human senses, i.e. visual, acoustical, and spatial experience as is the case with architectural or environmental worlds, like sound installations and artistic / sonic environments. Xenakis anticipated the genre of sound installations long before this term has been coined towards the end of the 20th century. Today, more and more sonic artists extend their artistic experience to visuals, and they often combine their performances with video screenings and / or installation environments. One interesting example is Reinhold Friedl’s Zeitkratzer project called “Xenakis Alive !” where they produce Xenakian “electronic” sound live on stage with classical music instruments, together with a video by Lillevan [Friedl 2007]. I call their performance “un-acousmatic” music since they turn upside-down the acousmatic experience of studio-produced loudspeaker-only music into a life event on stage, put into an immersive setting.

3. UPIC SESSIONS AND KANAL GENDYN : EMERGENCE AND IMMERSION

From 2004, Russell Haswell, a noisician from England, and Florian Hecker, a conceptual plastic and sound artist, unite on a regular basis for their “UPIC diffusion sessions”, using material they produced during a residency at Ateliers UPIC, Paris, back in 2004. Every one of these UPIC sessions is unique in that Russell and Florian project their UPIC sounds into ever new immersive installation and / or stage situations. They also used an interactive version of GENDYN made by Alberto de Campo, in a performance situation in conjunction with an avant-garde video made by the Swiss duo Weiss and Fischli at the Musterraum in Munich (2004). The Musterraum (German for “reference room”) was a temporary construction, a cube, which was built as a test and reference space for the planning and the construction of the adjacent museum building, the Pinakotek der Moderne.

Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker are the only artists whom I know who have published both music made with UPIC and GENDYN on CD (and vinyl), e.g. [Haswell&Hecker 2007], [Haswell&Hecker 2011]. As an example of a Haswell & Hecker UPIC diffusion session, I took for my London talk an excerpt from session # 17 (captured in Riga in 2008) which I found on youtube [Haswell & Hecker 2008]. You can find excerpts of other such events there, but I think one can only guess their intensity from the videos.

3.1. UPIC recording sessions

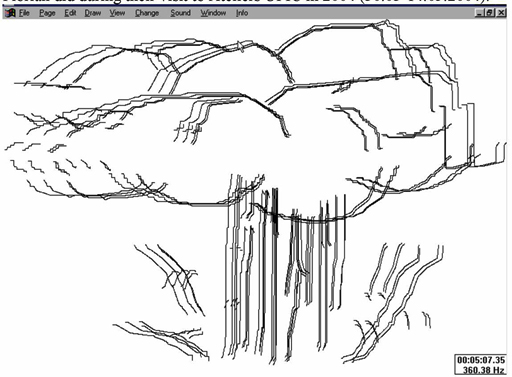

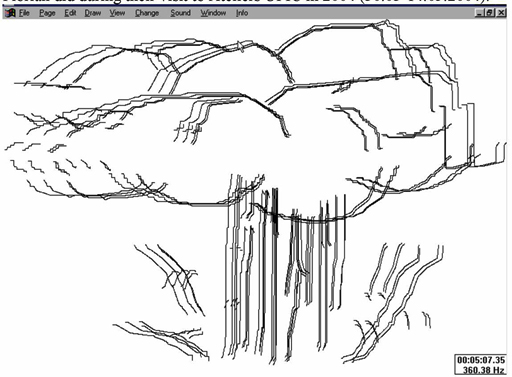

Here is one of the many designs on the UPIC system that Russell and Florian did during their visit to Ateliers UPIC in 2004 (30.03-14.05.2004).

Figure 3. One of the UPIC pages (time vs. frequency plots) that Haswell&Hecker created in 2004 during a visit to Ateliers UPIC near Paris (© Russell Haswell & Florian Hecker, 2004, UPIC Score). The UPIC system installed in this computer music studio was version 3, with a hardware box containing a bank of 64 wavetable oscillators and a Windows software controlling these oscillators in real time via a collection of hand-drawn plots (pages, waveforms, envelopes, amplitude and frequency mappings, and a sequencer plot) and lists combining these plots to make sound. The numbers in the lower right rectangle show the position of the cursor in time resp. frequency.

There is a very informative article written by Haswell & Hecker together with Robin Mackay in his philosophical / aesthetical periodical COLLAPSE [Mackay 2007]. Several of their UPIC drawings have been included in this article. The one reproduced here, for example, is a time versus frequency plot (a “page” in UPIC terms) which represents the mushroom of an atomic bomb explosion. I asked Russell and Florian if they expected to create the acoustic impact of an atomic bomb explosion and, of course, they denied. Indeed, this page does sound very different from an explosion, since it’s a two-dimensional time versus frequency plot. Think of this page as a sort of piano roll but with continuous rise and fall of pitch (reminiscent of Xenakis’ beloved webs of glissandi). For Russell and Florian, the atomic bomb picture was just a means to get acquainted to UPIC’s way of functioning. Some composers spent a year struggling with the UPIC before they got a piece of music out of it. Some say that UPIC is a very tough pedagogical tool teaching a composer to rethink everything about composing. In any case, the fact that Russell and Florian got enough good material out of the UPIC for their UPIC sessions and their CD releases tells a lot about their mastering of machinery – even if it’s complicated they get out of it what they want.

Figure 4. A still image from a screening of a typical „UPIC diffusion session“ (Riga 2008), published on youtube [Haswell&Hecker 2008]

3.2. Kanal GENDYN (1992 / 2004 / 2011)

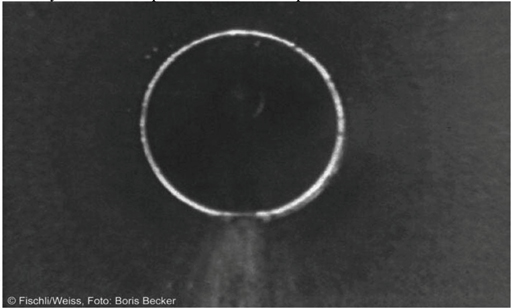

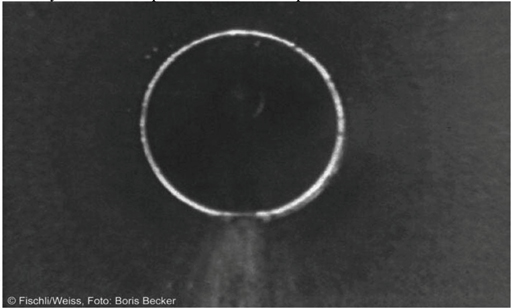

Kanal GENDYN was performed by Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker in 2004 at the Musterraum in Munich. The Musterraum hosted a series of events, among them the screening of a 1-hour-long video (1992) by Swiss visual artists David Weiss and Peter Fischli. Synchronous to the screening, Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker performed live and in real-time on stage with the program GENDYN choir, a special GENDYN implementation made by Austrian composer Alberto de Campo.

Figure 5. A still image from the Kanal video by Fischli and Weiss (1992), a 1-hour recording of a sewage inspection camera going through the Zurich underground. Concurrent to the screening of this video in 2004 at Musterraum, Munich, Haswell & Hecker performed live with the GENDYN Choir program made by Alberto de Campo. (The original is in color)

As Haswell & Hecker state :

“This video, which consists of an hour long ‘ride’ through the Zürich sewage system, with a remotely controlled maintenance vehicle equipped with a video camera to surveil the sewers for eventual irregularities or defects - struck us both as an ideal piece to be projected in a ‘nightclub’ or music venue with a GENDYN only performance. We found twisted relations with such an hour long ‘tunnel vision’. Once with the seemingly endless amount of computer generated video projections used as visual accompanying raves and techno parties during the 1990’s - and also to the accounts of visual hallucinations induced by Mescaline as described by Heinrich Klüver in the 1920’s - with the so called ‘form constants’ - where he mentions amongst others ‘tunnel like’ patterns. The particularities of GENDYN, with its ever changing and meandering waveforms appeared to us as an ideal counterpart.” [Hoffmann 2011b]

Kanal GENDYN was released on both Vinyl and 24 bit DVD in 2011 [Haswell&Hecker 2011].

The immersiveness of the Kanal GENDYN performance was a product of the specific architectural site, the Munich Musterraum, the screening of the mesmerizing and hypnotizing tunnel video and the unfolding of the artificial but evocative sound world from the GENDYN sound composition tool. As stated above, GENDYN sound is the result of stochastic processes acting on a sample level of sound, on so-called sound “segments” forming higher-order sound properties like pitch and timbre, and also rhythmic patterns by a process of emergence out of the transformation of these sample-level segments. And the way Haswell & Hecker invocated these emergent sound processes adds even more emergence to it, since they used a multi-voiced, interactive, real-time implementation of GENDYN, Alberto de Campo’s GENDYN choir program. Therefore, the cybernetics of GENDYN sound synthesis were complemented by the cybernetics of real-time (self) control as well as interactive (mutual) control between the two collaborating sound artists, creating a web of interdependencies acting on the acoustic / visual immersive environment.

4. CONCLUSION

The ideas Xenakis has left us are still valid today. Even more so, they only seem to really unfold their full potential in our time, 12 years after Xenakis’ death. Xenakis lived too early to experience the full impact of his artistic thought onto art. The interaction of graphics and sound is still researched and developed. Stochastic Synthesis has just begun its career in music production. Emergent Composition has a Golden Future. Immersive multimedia events are en vogue. And there are more aspects to Xenakis’ artistic legacy which radiate into the present and future. Xenakis’ ideas are virulent, Xenakis’ thought is contagious and prone to ever-spreading epidemics. It has already transgressed the genres and crossed over to the underground, industrial and noise scene, and is now part of the remix and clubbing culture. This propagation is unparalleled by any other avant-garde composer I know of.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Dimitris Exarchos and Haris Kittos who brought me onto the track of post-Xenakian research by inviting me to their 2011 London conference, and to Makis Solomos who enabled a panel discussion with Alberto De Campo, Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker on his Paris Conference in 2012, and of course, to all Post-Xenakians of the present and future !

6. REFERENCES

[Aristotle Metaphysics] Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book H (8) 1045a 8-10, quoted after Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergence, last visit 15.01.2014.

[Bökesoy 2013] Bökesoy, Sinan, sonicLAB : Creative Tools for Advanced Sonic Synthesis, http://www.sonic-lab.com/, last visit 12.01.2014.

[Coduys 2004] Coduys, Thierry, Iannix. Aesthetical / Symbolic visualizations for hypermedia composition, http://www.iannix.org/en/education/, last visit 12.01.2014.

[Collins 2012] Collins, Nick, Even More Errant Sound Synthesis, Sound and Music Computing, 2012, www.sussex.ac.uk/Users/nc81/research/evenmoreerrant.pdf, last visit 11.01.14.

[DiScipio 1997] Di Scipio, Agostino, The Problem of 2nd-order Sonorities in Xenakis’ Electroacoustic Music, Organised Sound : Vol. 2 (1997), no. 3, pp. 165-178.

[DiScipio 2001] DiScipio, Agostino, Clarification on Xenakis : the Cybernetics of Stochastic Music, in : M.Solomos (ed.), Présences de / Presences of Iannis Xenakis, Paris : Cdmc, (2001), pp. 71-84.

[DiScipio 2003] Sound is the Interface : From interactive to ecosystemic signal processing, Organised Sound vol. 8 (2003), no. 3, pp. 269-277

[DiScipio 2008] DiScipio, Agostino, L’émergence du son, le son de l’émergence, in : A. Sedes (ed.), Musique et cognition, Intellectica 48 (2008), pp. 221-249.

[Doornbusch 2002] Doornbusch, Paul, G4, CD Corrosion, Electronic Music Foundation, 2002 (EMF 043).

[Doornbusch 2010] Doornbusch, Paul, Mapping in Algorithmic Composition and Related Practices, PhD diss., RMIT Univ. in Melbourne, 2010 ; see also http://www.doornbusch.net/, last visit on 02.02.2014.

[EVL 2004] Electronic Visualization Lab, Website, http://www.evl.uic.edu/pape/CAVE/, last visit 24.01.2014.

[Friedl 2007] Friedl, Reinhold, Xenakis

[A]Live !, performed by Zeitkratzer, CD+DVD, Asphodel, 2007 (ASP 3005).

[Haswell&Hecker 2007] Haswell, Russell ; Hecker, Florian, Blackest Ever Black, Electroacoustic UPIC Recordings, 2x12’’ Vinyl and CD, Warner Music Ltd, UK, 2007.

[Haswell&Hecker 2008] UPIC diffusion session #17, Riga, 09.05.2008, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68H3z7IItyU, last visit 31.01.2014.

[Haswell&Hecker2011] Haswell, Russell ; Hecker, Florian, Kanal GENDYN, DVD 24 bit & 12” Vinyl, Editions Mego, Wien, 2011.

[Hoffmann 2009] Hoffmann, Peter, Music out of Nothing ? A Rigorous Algorithmic Approach to Computer Composition by Iannis Xenakis, PhD diss., Technical University of Berlin, 2009, http://opus.kobv.de/tuberlin/volltexte/2009/2410/pdf/hoffmann_peter.pdf, last visit 12.01.14.

[Hoffmann 2011a] Hoffmann, Peter,

[Sleeve notes to Russell Haswell’s and Florian Hecker’s Kanal GENDYN Recording], LP / DVD, Russell Haswell & Florian Hecker : Kanal GENDYN, Editions Mego, www.editionsmego.com.

[Hoffmann 2011b] Hoffmann, Peter, „Xenakis Alive !“ Explorations and extensions of Xenakis’ electroacoustic thought by selected artists, Proceedings of the Xenakis International Symposium, Southbank Centre, London, 01.-03.04.2011 http://www.gold.ac.uk/media/Keynote%20II%20Peter%20Hoffmann.pdf (last visit 02.02.2014).

[Hoffmann 2012] Peter Hoffmann, Forum „Post-Xenakians”. Interactive, Collaborative, Explorative, Visual, Immediate : Alberto de Campo, Russell Haswell, Florian Hecker, in : Makis Solomos, (ed.), Proceedings of the International Symposium Xenakis. La musique électroacoustique/ Xenakis. The Electroacoustic Music (Université Paris 8, May 2012), http://www.cdmc.asso.fr/sites/default/files/texte/pdf/rencontres/intervention7_xenakis_electroacoustique.pdf, last visit 02.02.2014.

[Lewes 1875] Lewes, G. H., Problems of Life and Mind (First Series), vol. 2, London : Trübner, p. 412, quoted after Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergence, last visit 15.01.14.

[Mackay 2007] Mackay, Robin, Blackest Ever Black : Rediscovering The Polyagogy of Abstract Matter (in collaboration with Russell Haswell and Florian Hecker). In : COLLAPSE III, ed. Robin Mackay, Falmouth, Urbanomic, Nov. 2007, pp. 109-139, http://www.urbanomic.com/dlprocess.php?file_location=Publications/Collapse-3/PDFs/C3_Haswell_Hecker.pdf, last visit 02.02.2014.

[Marino 1993] Marino, Gérard ; Serra, Marie-Hélène ; Raczinski, Jean-Michel, The UPIC System : Origins and Innovations. Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 31 (1993), No 1.

[Revault d’Allonnes 1975] Revault d’Allonnes Olivier, Xenakis : Les Polytopes, Paris, Balland, 1975.

[O’Reilly 2003] O’Reilly, Brian, octal_hatch, Hommage to Iannis Xenakis, http://vimeo.com/7662715, last visit 01.12.2014.

[Roads 1978] Curtis Roads. Automated granular synthesis of sound. Computer Music Journal, 2(2) :61–62, 1978. revised and updated version in Curtis Roads and John Strawn, editors, Foundations of Computer Music, pages 145–159. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, London, 1985.

[Sterken 2004] Sterken Sven, Iannis Xenakis, ingénieur et architecte. Une analyse thématique de l’œuvre, suivie d’un inventaire critique de la collaboration avec Le Corbusier, des projets architecturaux et des installations réalisées dans le domaine du multimédia, PhD thesis, Gent University, 2004.

[Wikipedia Immersion], http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immersion_%28virtual_reality%29, last visit 25.01.2014

[Xenakis 1992] Iannis Xenakis. Formalized Music. Thought and Mathematics in Composition. Pendragon Press, Stuyvesant NY, 1992. revised edition, with additional material compiled by Sharon Kanach.