|

The New World Literature |

|

The New World Literature |

In the summer of 1949, at the Goethe Convocation in Aspen, Colorado, organized by University of Chicago chancellor Robert Maynard Hutchins, novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder proclaimed that Goethe, in predicting in 1827 that an epoch of world literature was at hand, had “spoke[n] too soon.” Wilder announced that “it is now during the second quarter of the twentieth century that we are aware of the appearance of a literature which assumes that the world is an indivisible unit.”1 Wilder’s examples of this world literature—T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ezra Pound—are predictably modernist, and the location and occasion of his speech, a conference in the United States organized by an influential theorist of higher education and proponent of the “Great Books” program, indicate the degree to which high modernism had by 1949 been embraced by the American university, effectively institutionalizing Wilder’s version of Goethe’s vision. Over the next two decades, as the university population expanded exponentially, this revised vision of world literature would come to inform the reading habits and cultural sensibilities of a considerable fraction of the American public.

Wilder’s modernist elaboration of Goethe’s romantic vision clearly implies a canon of texts based both in a certain idea of aesthetic value and in a certain consciousness of cultural diversity, but David Damrosch has recently reminded us that “world literature is not an infinite, ungraspable canon of works but rather a mode of circulation and of reading.”2 According to Damrosch, the category of world literature simply designates “literary works that circulate beyond their culture of origin.”3 Wilder’s modernist definition, as illustrated by the Grove Press catalog, is the object of my analysis in this chapter, but I rely on Damrosch’s more pragmatic definition for my method of analysis, which helpfully recognizes the importance of publishers, editors, and translators as crucial nodes in the network that enables this category to exist in the first place. Through close alliances with academics and translators across the country, Grove helped popularize a concept of world literature in the late 1950s that centrally informed the political investments of the counterculture in the 1960s.

Barney Rosset and his team at Grove were, like Wilder, steeped in European modernism, and many of the major writers they made available in the United States—Samuel Beckett, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jean Genet—represented the final stages of the high modernism that had reigned between the wars and whose cultural capital had been Paris. But the political and cultural status of Europe had been transformed by the cataclysms of World War II. Grove’s vision of world literature was also inflected by the decolonization of the European empires and the inception of the American century. From its beginnings, Grove worked to provide an American venue for the literature of the “new nations” rapidly emerging from the old empires, and of the so-called Third World more generally, making available many of the authors who formed the initial core of what later came to be known as postcolonial literature. In this sense, Grove can be understood as a central participant in what Casanova identifies as the third major stage in “the genesis of world literary space,” which is marked by the entry of the new nations into international competition for literary recognition.4 The resulting canon can be formulated as a version of what Mark McGurl calls “high cultural pluralism,” literature that combines modernist formal experimentation with “a rhetorical performance of group membership.”5

Grove’s embrace of an expanded canon of world literature was enabled by the postwar mandate for cultural exchange elaborated by UNESCO, whose imprimatur appears on many of the texts discussed here. UNESCO’s constitution, adopted in 1945, claims that “the wide diffusion of culture, and the education of humanity for justice and liberty and peace are indispensable to the dignity of man.” It affirms that “a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind.”6 The perceived urgency of this mandate at the inception of the atomic age is well illustrated by Archibald MacLeish’s opening statement at the meeting of the American delegation to the organization’s constituent conference in 1945, which emphasizes “the crucial importance of its success if the civilization of our time is to be saved from annihilation.”7

As William Preston, Edward Herman, and Herbert Schiller confirm in their history of the vexed relations between UNESCO and the United States, “UNESCO’s origin had been a utopian yet necessary invention in international cooperation, and the attempted elevation of educational and cultural relations to the forefront of world diplomacy was equally adventurous. Both represented the growing intensity of international contacts, as technology, communications, and economic interchange reduced the distance between the world’s diverse populations.”8 Preston, Herman, and Schiller are predominantly concerned with the role of mass media in this globalizing process, but UNESCO was also heavily invested in promoting and enhancing the distribution of books around the world. In 1956, it published R. E. Barker’s study of the international book trade, Books for All; and ten years later, Robert Escarpit’s The Book Revolution, which opens with the claim that, due to innovations in paperback publishing, “over the last decade everything has been transformed—books, readers and literature.”9 In subsidizing and circulating studies such as Barker’s and Escarpit’s, UNESCO hoped to harness the energies and technologies of the paperback revolution in the service of cultural exchange.

Furthermore, as Christopher Pearson affirms in his fascinating study of UNESCO’s architectural and artistic heritage, “The pan-national idealism that underlay its institutional activities found an immediate parallel in the ideologies of modern art and architecture” that informed its design and many of its cultural policies.10 UNESCO, in other words, emerged at the “confluence of two ideas—international modernism and international cooperation.”11 In this sense, UNESCO’s location in Paris is equally significant. As is clear from the published notes of Luther Evans, UNESCO’s fourth director general, reporting on the meetings of the American delegation to the 1945 constituent conference, a consensus quickly developed that if the United Nations was to be located in the United States, UNESCO would have to be located elsewhere, and Paris, as a “natural cultural center,” quickly rose to the top of the list.12 When the British proposed the French capital as headquarters of the nascent organization, “Senator [James] Murray then went all out for Paris. Others followed in the same vein—Belgium, Mexico, China, Colombia, etc. The French were highly elated.”13 Aesthetically integrated into the cityscape, UNESCO would help Paris maintain its centrality to the circulation and consecration of culture during the period of decolonization.

Literary authorship in this cultural constellation attained a new stature of diplomatic statesmanship, conferring a mantle of ethical authority on figures of internationally recognized literary achievement. The modernist “exile” of the author, which between the wars had been resolutely apolitical and solitary (if not downright reactionary), attained a diplomatic significance as literary figures, officially or informally, took on the burdens of UNESCO’s mandate to heal the world through cultural exchange. A number of important Grove authors during this period, including Nobel Prize winners Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda, were themselves diplomats who were able to leverage their literary capital into political influence on the international stage.

To facilitate its vision of world literature, Grove employed a veritable army of translators who played a crucial role in negotiating the tensions between cultural elitism and cultural pluralism that informed its title list. As Casanova affirms, translation is a form of consecration that operates in two directions, depending on the relation between source and target languages. On the one hand, it is a mechanism whereby literary capital from the European center, principally Paris, can be diverted into the periphery; on the other, it enables texts written in peripheral languages to be recognized by literary authorities in the center. Grove worked in both directions, siphoning literary prestige from Paris to New York by translating figures such as Beckett, Robbe-Grillet, and Genet but also expanding international recognition for work written in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Richard Howard, Bernard Frechtman, Ben Belitt, Lysander Kemp, and a host of other translators, many of whom were poets themselves and most of whom found their professional home in the American university system, not only translated key authors for Grove but also acted as liaisons and consultants in the international literary network that Grove helped build in the postwar era.

Most of Grove’s translators can be positioned within what Lawrence Venuti, in his contentious history The Translator’s Invisibility, analyzes as the modernist regime in English-language translation, which “seeks to establish the aesthetic autonomy of the translated text” through assimilating it to the modernist criteria of its target language.14 Venuti’s somewhat selective history mentions none of Grove’s translators, but Paul Blackburn, the Poundian disciple who receives pride of place in The Translator’s Invisibility, was well aware of Grove’s importance when, in a 1962 article for the Nation, he ambivalently proclaims, “Now that colonialism has become an anachronism politically . . . it is as though we are witnessing the sack of world literature . . . by the American publishing business.”15 Citing a number of Grove’s authors and translators, as well as the Mexican issue of the Evergreen Review that is discussed in detail later, Blackburn is cautiously optimistic, averring that “the mutual insemination of cultures is an important step toward what our policy makers think of as international understanding.”16

Grove’s cultivation of an international title list coincided with its innovation of the quality paperback, a conjunction that affected the cultural understandings of both categories. On the one hand, world literature, while maintaining the scholarly imprimatur of its translators and introducers, would be inexpensive and accessible, and Grove’s translators explicitly targeted a broad Englishspeaking American public. On the other hand, Grove’s Evergreen Originals took on the worldly and cosmopolitan cast of the contents they frequently contained. Thus, over the course of the 1950s, Grove established an identity as a source of affordable access to the latest developments in world literature. Kuhlman’s abstract expressionist cover designs provided aesthetic continuity for the various literary products Grove offered. By packaging a wide variety of titles from all over the world under a uniform style of aesthetic innovation already associated with the postwar ascendance of the United States, Grove’s Evergreen Originals, in their very format, accommodated the cultural pluralism of world literature to the cultural elitism of late modernism. And Grove aggressively marketed its international titles to an academic audience, announcing in one flyer circulated to colleges and universities that “Evergreen books have a particular interest for Humanities and World Literature courses. They represent an unusually wide range, from ancient classics of China to the latest novels from France” and boasting “the greatest number of individual titles being used this past year by Harvard University, the University of Chicago, and the University of California at Los Angeles.”17

Two anecdotes, both set in Paris in the late 1950s, exemplify the network whose general shape I’ve just outlined. The first involves Khuswant Singh, the Sikh author and diplomat who in 1954 became a specialist in Indian affairs for the Department of Mass Communications at UNESCO. In 1955, Rosset, apparently not patient enough to acquire authors and then wait for them to win international prizes, decided to establish his own “Grove Press Contest for Indian Writers” in order “to further cultural relations between the United States and India,” with an award of one thousand dollars to be given to “the best literary work in English to be submitted by a citizen of India.”18 The press received more than 250 submissions, from which a panel of two Indian and two American judges selected Singh’s Mano Majra, a novel focusing on the violence and unrest in a small town on the newly established India-Pakistan border.19

The ensuing negotiations over the award and the novel’s publication conveniently illustrate the institutional linkages through which Grove built its international reputation. Upon hearing that he had received the award, Singh wrote to Rosset, “I would very much like the presentation to be made by my own Director General, Dr. Luther Evans . . . It would do my ego a lot of good.”20 Rosset promptly wrote to Evans, the former librarian of Congress, who agreed to present the award, writing that “Mr. Singh’s work will contribute to increasing mutual knowledge among peoples of one another’s ways of life, which is one of the fundamental aims of UNESCO.”21 The award was presented to Singh on March 18, 1955, in the Louis XIV room of UNESCO House in Paris.

In his letter accepting the award, Singh suggested changing the title to Train to Pakistan, calling it a “cheaper title” that will “tempt reviewers to review, buyers to buy and even film companies to look upon it as a possibility. A train is a Freudian symbol which arouses a response at once.”22 Rosset preferred the original title, and the novel was initially published under both titles, though Train to Pakistan is the one that stuck (a movie was eventually made in 1998). Rosset also quickly secured translation deals with Gallimard and Verlag and granted British publication rights to Chatto and Windus. Grove then aggressively publicized the text as a “prize-winning novel” in both India and the United States. The story of Grove’s acquisition and publication of Singh’s novel economically illustrates the alignments between literary prestige, as conferred by the proliferating system of awards, and cultural exchange, as represented by UNESCO, that shaped the network in which Grove’s vision of world literature circulated.

The second anecdote involves Richard Howard, the prize-winning American poet who translated key authors for Grove, including Alain Robbe-Grillet, Fernando Arrabal, and André Breton. In January 1959, Rosset sent Howard on a trip to Paris with an illuminating list of tasks. For the Evergreen Review, Howard was to solicit an article by Roland Barthes on “the current situation of the intellectual in France” and one by René Étiemble on “Red China.” He was to study current productions of Arrabal’s plays, with particular attention to “his use of the contemporary jazz idiom.” He was to contact editors at Éditions de Minuit, Éditions du Seuil, and Gallimard concerning their latest projects. He was to visit Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, partly to check up on the progress of the Lolita Nightclub (Girodias had achieved considerable notoriety for publishing Nabokov’s novel as part of his Traveler’s Companion series in 1955). And he was to look for a cartoonist.23

Howard’s letters to Rosset provide insight into the formation of the network whereby Grove obtained most of its early access to an emergent international literary canon. He exults that he has “never had so many invitations to dinner, to lunch, to drinks, to talk . . . in all [his] life.” He reports to Rosset that, based on his visits with Parisian publishers, “we have every reason to feel that the intellectual richesse of France will be showered upon Grove Press.” And he exclaims that, in Paris, “Evergreen Review and Grove Press are perhaps the best known American manifestations of The Higher Culture.” Finally, he notes that “there is a huge Jackson Pollock show [that] Frank O’Hara was here to hang.”24

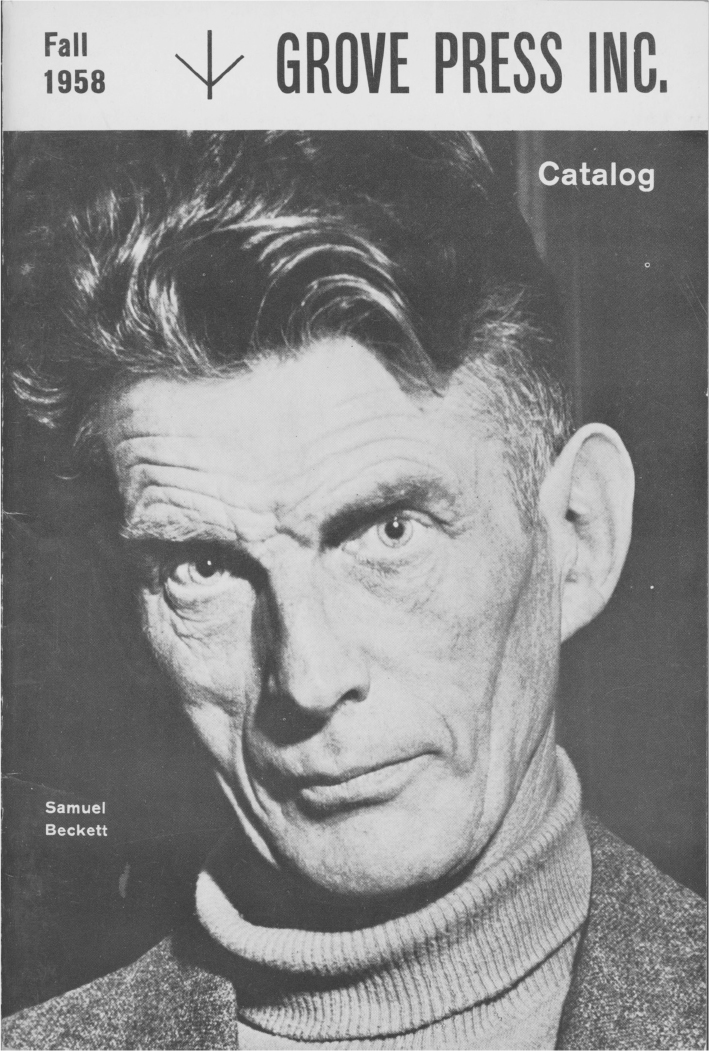

But Howard’s most remarkable encounter is with Samuel Beckett, to whom Rosset had written a letter of introduction. Like almost everyone who writes about Beckett personally, Howard was smitten: “I was expecting that fierce, beautiful head that you use on your catalogue, but nothing had prepared me for the gentleness of his voice, the warmth of his welcome, and the fascination of his presence.” The two, not surprisingly, discuss translation, with Beckett affirming that “he does not translate, he creates.” Howard then recounts a remarkable story Beckett told him of a visit in 1940 to Valery Larbaud, the French author and translator of Ulysses under whose “patronage” Casanova places The World Republic of Letters. Larbaud was paralyzed as a result of illness, and Howard sees in this visit the genesis of the narrator of Beckett’s Unnamable: “Surely the vision of that motionless, ignoble trunk babbling incoherent syllables . . . must have caught somewhere within Beckett’s fierce head, his formidable heart,” Howard provocatively speculates.25

The modernist credentials of Beckett—apprentice to Joyce, critic of Proust, continuously compared to Kafka—were impeccable. Rosset shrewdly anticipated that, like his modernist forebears, Beckett would make a good long-term investment. By 1955, he was already able to announce to Beckett, with whom he had become friends, “I am very happy to see this bubbling up of interest and my strong feeling is that your work is going to be more and more known as time goes by. There definitely is an underground interest here, the kind of interest that slowly generates steam and has a lasting effect.”26 In fact, Beckett was canonized with such unprecedented alacrity that Leo Bersani felt the need to ask, in his review of Martin Esslin’s 1965 anthology of critical essays on the author, “Has Beckett . . . failed to fail?”27 Bersani’s review reveals how the academic industry that rapidly inserted itself into the interpretive space left open by Beckett’s reticence effectively universalized his idiosyncratic literary response to the devastation and destitution of postwar Europe into an expression of “the nature of human existence itself.”28 Bersani finds it “somewhat disconcerting to read so many admiring, undaunted analyses of a significance for which Beckett implicitly expresses only boredom and disgust,”29 but Esslin has a response to this understandable complaint. He asks in his introduction, “If there are no secure meanings to be established . . . what justification can there be for any critical analyses of such a writer’s work?” He then lists a number of justifications, including elucidating “the numerous allusions” and uncovering “the structural principles.” But both of these justifications rely for their ultimate utility on the third, which makes it the role of the critic to determine “the manner in which [Beckett’s] work is perceived and experienced by his readers.” For Esslin, “the critics’ experience . . . serves as an exemplar for the reactions of a wider public; they are the sense organs of the main body of readers.” Implicitly referencing the rocky initial reception of Waiting for Godot in the United States, Esslin explains that the critics’ “modes of perception will be followed by the mass of readers, just as in every theater audience it is the few individuals with a keener than average sense of humor who determine whether the jokes in a play will be laughed at at all, and to what extent, by triggering off the chain-reaction of the mass of the audience.”30

Esslin’s collection displays a cultural confidence in the gate-keeping function of critics that derives, in somewhat circular fashion, not only from their consensus on Beckett’s importance but also from the shared network of venues in which this consensus circulated. Their spectacular success in inverting Beckett’s failure received the ultimate imprimatur three years later, when Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for, in the peculiar syntax of the Swedish Academy, “his writing which—in new forms for the novel and drama—in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation.” Karl Ragnar Gierow’s speech, given in Beckett’s absence, clarified this powerful logic of reversal. Conceding that “the degradation of humanity is a recurrent theme in Beckett’s writing,” Gierow goes on to ask, “What does one get when a negative is printed? A positive, a clarification, with black proving to be the light of day, the parts in deepest shade those which reflect the light source. Its name is fellow-feeling, charity.”31

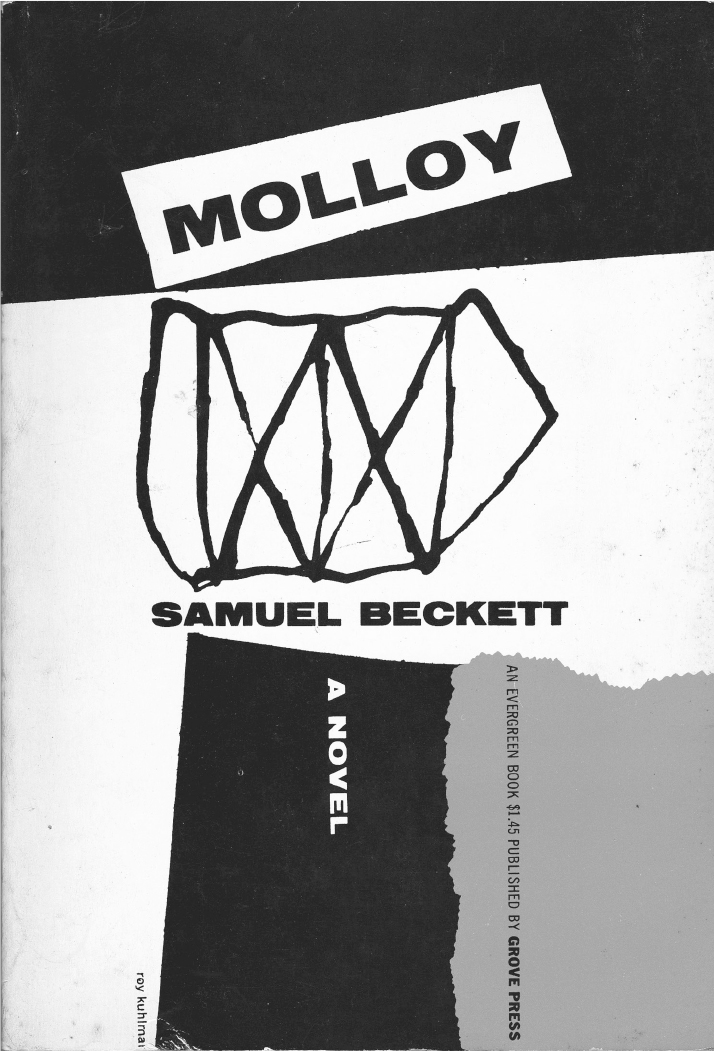

Gierow’s photographic metaphor is revealing, since this humanist universalization of Beckett’s themes tended to be reinforced by analogies to the visual arts. Esslin’s collection exhibits this tendency by opening with Beckett’s “Three Dialogues on Painting,” which includes his famous assertion, offered as an appraisal of the Dutch painter Bram Van Velde but widely understood as an instance of critical self-reflection, that, in the absence of any coherent relation between artist and occasion, “to be an artist is to fail, as no other dare fail.”32 As the essays that follow reveal, it would be left to the critics to establish this relation, frequently by analogy to abstract painting. Grove’s book design reinforced this analogy, as Kuhlman ensured that the covers for the individual paperbacks of Beckett’s postwar trilogy sported the abstract expressionist designs he favored. Thus, the title Molloy jauntily tilts across the top of the cover, in black type framed by an irregular strip of white slanted against a black background. In the center, Beckett’s name appears directly below an abstract design drawn in black lines of irregular thickness against a white background. The abstract, typographical, and thematic elements of the cover are brought together by the central geometric line drawing, which depicts two large black X’s framed by adjacent rectangles (Figure 6). The cover reframes themes of constraint—the abstract design suggests bars or grids—as an image of formal free play. As an aesthetic object in and of itself, it encourages more generally the sublimation of thematic meaning into formal abstraction and stylistic virtuosity.

For the single-volume hardcover edition, offered as an alternate selection by the Readers’ Subscription in 1959, Grove used the photo Howard mentions from its 1958 catalog cover, which appeared in advertisements and promotional materials throughout the 1960s. It features Beckett from the shoulders up, facing front but with his head slightly turned to the right and his forehead slanted forward, giving his direct gaze into the camera a vaguely menacing aura. He’s wearing a turtleneck sweater and a tweed jacket, and his thick hair is combed straight up off his forehead and cut very short above his ears. His left ear is prominently visible, giving the sense that he is listening skeptically. He looks like a highly intelligent, and intimidating, college professor, buttressing Hugh Kenner’s contention, in his early study of Beckett published by Grove in 1961 and excerpted in Esslin’s anthology, that his work “plays ever bleaker homage to the fact that ours is a classroom civilization, and that schoolmasters are the unacknowledged legislators of the race”33 (Figure 7).

Since Beckett couldn’t come up with a single title for the trilogy, Grove simply presents it on the jacket cover in yellow as Three Novels by Samuel Beckett to the lower left with the individual titles, also in yellow, to the lower right. The Black Cat paperback, which sold more than sixty thousand copies in its first five years, features simply Three Novels by Samuel Beckett in black, followed by Molloy in blue, Malone Dies in green, and The Unnamable in blue. Over the course of these serial iterations, Grove used all three of Kuhlman’s styles—abstract, photographic, and typographic—to package Beckett’s trilogy. And Beckett in turn ballasted Grove’s reputation, grounding and legitimating the modernist standards that dictated its choices of international authors. His austere gaze appears authoritatively in many of its ads, and his name, conveniently early in the alphabet, always fronts any list of its titles. The combination is epitomized by the covers for the collected works that Grove issued in the wake of Beckett’s Nobel Prize, all of which sport the now-classic photo in different colors.

Figure 6. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for Molloy (1955).

Figure 7. Grove Press catalog cover (Fall 1958). (GPC)

Beckett also provided a model for the practice of translation that was so central, philosophically and economically, to Grove’s international enterprise. Indeed, early correspondence confirms that Rosset should be given some credit for convincing Beckett to enter into the business of self-translation. In his first, and frequently cited, letter to Beckett, Rosset states emphatically, “If you would accept my first choice as translator the whole thing would be easily settled. That choice of course being you.”34 Beckett responded that he was willing to tackle Godot but that, concerning the novels, he would “greatly prefer not to undertake the job.”35 In his recently published memoirs, Seaver affirms Rosset’s role in encouraging Beckett to take up the task, quoting him as saying, “I always felt Beckett had to be his own translator . . . but he resisted for a long time.”36

As Paul Auster admiringly asserts in his “Editor’s Note” to the Grove Centenary Edition of Beckett’s complete works, “Beckett’s renderings of his own work are never literal, word-by-word transcriptions. They are free, highly inventive adaptations of the original text—or, perhaps more accurately, ‘repatriations’ from one language to the other, from one culture to the other. In effect, he wrote every work twice, and each version bears his own indelible mark, a style so distinctive it resists all attempts at imitation.”37 Auster’s shift from “adaptation” to “repatriation,” from “language” to “culture,” can be understood to indicate a certain “cultural turn” in the conventional understandings of translation, but he also invests the implied pluralism of this terminology with a model of modernist mastery indicated by the “indelible mark” of Beckett’s authorship. Grove’s translators were similarly split between an emergent cultural understanding of linguistic difference and a residual modernist understanding of literary value.

The difficult work of Alain Robbe-Grillet also solicited critical elucidation; unlike Beckett, Robbe-Grillet was eager to supply some of this elucidation himself. Robbe-Grillet claimed that he wrote the essays collected in For a New Novel because “I was not satisfied to be recognized, enjoyed, studied by the specialists who had encouraged me from the start; I was eager to write for a ‘reading public,’ I resented being considered a ‘difficult’ author,” which situates him within the mandate for popularizing modernism that also motivated his American publisher.38 His agent Georges Borchardt wrote to Grove about what became Robbe-Grillet’s most popular book in the United States: “la jalousie has not yet been seen by any American publisher. I think Grove is just right for it, and it is just right for Grove.”39 And Grove indeed worked hard to promote both Robbe-Grillet’s novels and his explanations of their technique, publishing a number of the essays in the Evergreen Review that were later collected in For a New Novel. The first, “A Future for the Novel,” specifies the degree to which the “New Novel” implies a “New World”: “Not only do we no longer consider the world as our own, our private property, designed according to our needs and readily domesticated, but we no longer even believe in its ‘depth.’”40 Robbe-Grillet’s abandonment of “depth” allied his literary program with the visual arts, in particular film, to which he increasingly turned in the 1960s after the success of Last Year at Marienbad. Two issues later the Evergreen Review featured Roland Barthes’s seminal essay on Robbe-Grillet, in which he affirmed that the author “requires only one mode of perception: the sense of sight.”41

Barthes’s essay formed one of the multiple paratexts inserted into the combined volume of Jealousy and In the Labyrinth that Grove published as a Black Cat paperback in 1965. According to Rosset, Robbe-Grillet, who had himself worked as an editor at Éditions de Minuit, had encouraged this repackaging of his most acclaimed novel during his US lecture tour, which the author claimed consisted of “forty universities and forty-three cocktail parties.”42 After the visit, Rosset wrote to Borchardt, “When Robbe-Grillet was here, we decided to do our own small format Evergreen containing jealousy and in the labyrinth, plus a section of critical material by and about Robbe-Grillet, specifically aimed at the college market. This is what Robbe-Grillet wants, and so do we. We hope for an enlargement of the audience for Robbe-Grillet in this manner.”43 This academically pitched Black Cat mass-market version, appearing in the same year as For a New Novel, in fact features three critical introductions: Barthes’s essay, a piece by the French critic Anne Minor, and one by University of Chicago professor Bruce Morrissette. These essays are followed by a map of the colonial villa in which the novel’s action takes place, accompanied by a detailed legend, orienting and emphasizing the spatial logic of the narrative to follow. The texts of the two novels are then supplemented, as stated on the back cover, by “a bibliography of writings by and about the author.” The back cover also prominently quotes an American reviewer’s prediction that “Robbe-Grillet will take his place in world literature as a successor of Balzac and Proust.” This paratextually packed “college” version of Robbe-Grillet’s most famous novel, which sold more than forty-five thousand copies over the course of the 1960s, affirms the degree to which his work found a home in the American academy. It is not surprising, then, that Howard, Robbe-Grillet’s American translator, also translated seminal work by Barthes and Michel Foucault, situating Robbe-Grillet in the advance guard for the army of French theorists who invaded the American university in the coming decades. Robbe-Grillet himself became a professor at New York University in 1971.

The final figure in Grove’s triumvirate of Parisian late modernist literary innovators is Jean Genet, who modeled the passage from aesthetic to political revolution that informs the larger story of Grove Press in the 1960s. On the one hand, Genet was widely perceived, in the frequently excerpted words of Alex Szogyi’s review of Our Lady of the Flowers for the New York Times Book Review, as “the foremost prince in the lineage of French poètes maudits.”44 Celebrated as heir to Baudelaire and Proust, Genet entered the English-speaking world with impeccable literary credentials, and his novels, once published, were widely celebrated as modernist masterpieces. On the other hand, the itinerant delinquency of Genet’s youth, coupled with the impassioned political militancy of his later career, turned him into something of a stateless diplomat, as he leveraged his literary celebrity into a tireless advocacy for the oppressed. As a figure of sexual dissidence who persistently associated himself with the causes of ethnic and racial minorities, especially the Black Panthers and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Genet anticipated the politics of difference that emerged from the social upheavals of the 1960s. More than any other single Grove author, his career exemplifies the complex convergence of the aesthetic, sexual, and political meanings of “revolution” that linked Grove’s early investment in European modernism with its later commitment to liberation movements around the world.

The philosophical framework within which this convergence was understood was resolutely existentialist, as Genet emerged onto the world stage in the enormous shadow of what Gerard Genette has called “the most imposing, or most inhibiting, example of philosophical support for a literary work,” Sartre’s monumental Saint Genet: Comedienne et martyr. Sartre’s work began as a preface to Gallimard’s edition of Genet’s collected works but turned into a six-hundred-plus-page tome issued by George Braziller in the United States in 1961 as Saint Genet: Actor and Martyr, the same year Grove brought out its hardcover edition of Our Lady of the Flowers.45 Saint Genet, from which Grove excerpted its prefaces to The Maids, Our Lady of the Flowers, and The Thief’s Journal, ensured that Genet’s development from thief to prisoner to poet to playwright to political radical, as well as the homosexual identity that subtends this development, would be understood dialectically, as willed appropriations of and identifications with an entire series of “others” against which the Western bourgeoisie defined itself.

Genet’s entry into the English-speaking world was also enabled by a less celebrated figure, Bernard Frechtman, the American expatriate who translated all his major work, as well as much of Sartre’s enormous corpus, including Saint Genet. Frechtman, a brilliant but emotionally unstable man with unrealized literary aspirations of his own, not only translated Genet’s difficult work into English but also operated as his literary agent until their break in the mid-1960s, after which he descended into a deep depression that ended in suicide in 1967. Prior to their break, Frechtman had been a tireless advocate of Genet’s genius, writing to Rosset in the early 1950s that “Genet—I haven’t the slightest doubt about this—is the greatest living writer.”46 Frechtman also specified that translating Genet presented particular challenges: “You do realize that translating Genet is not like translating an ordinary book. I’m generally a very fast worker and have a certain routine for handling translations. But works by Genet, as you well know, are another matter. I cannot stand outside them, as I can when translating ‘just another book.’ I must, after a fashion, become the book.”47 Frechtman inserts himself as yet another double in the narcissistic hall of mirrors that constitutes Genet’s Sartrian universe.

Significantly, Frechtman’s break with Genet was precipitated by a dispute over their respective share in the revenues from the paperback deal that Grove made with Bantam Books in the mid-1960s. Rosset had delayed publishing Genet’s sexually explicit novels until after his success in the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Thus, the plays, written after the novels, were both published and performed in the United States before the novels became available. Even after his triumph with Lady Chatterley, Rosset was cautious with the explicit homosexuality of Genet’s prose, first excerpting Our Lady of the Flowers in the Evergreen Review in 1961 and then issuing it as a hardcover, and a Readers’ Subscription choice, in 1963. After this hardcover edition received the unanimous acclaim of American critics such as Susan Sontag, Richard Wright, and Wallace Fowlie, Grove sold the paperback rights in 1964 to Bantam, which reissued it as a Bantam Modern Classic in 1968, by which time it had gone through five print runs. This delayed publication meant that Genet’s novels, while written in the 1940s, did not fully enter into the American cultural field until the 1960s, when they were rapidly canonized and widely circulated.

Beckett, Robbe-Grillet, and Genet represent the long twilight of the European male modernist as authoritative genius. All three men remain best known for their early work, which presents masculine protagonists in situations of impotence, confusion, and constraint, whose only dignity is granted through the stylistic virtuosity of their creators. While these thematic obsessions were frequently honored with celebrations of universality, they were also understood, with equal frequency, as representing the exhaustion not only of the modernist mandate to make it new but also of the entire Enlightenment project of epistemological mastery. The sense that the West had exhausted its ethical authority in the wake of a war that witnessed both the Holocaust and the atom bomb deeply informed Grove’s investment in other cultural traditions. Its selection of these traditions was in turn informed by America’s triumphant emergence from the war and the demands of its rapidly expanding university population for knowledge of the world the war had created.

In early 1953, Donald Allen began negotiations with Donald Keene, whom he had met and befriended in the Pacific during the war, over the publication of an anthology of Japanese literature. Allen described his vision to Keene as “a fairly large book, as complete as possible within such limits, and we’d like to present fairly long selections from the best Japanese writing together with informative prefatory notes that would somehow sketch in the history of Japanese literature. We aim to put together a book that will have some value as a textbook, we hope, but that will also appeal to the general reader.”48 Allen and Rosset also hoped that Keene could recruit Arthur Waley, by then the éminence grise of Oriental studies in the Anglophone world and translator of numerous works of classical Japanese and Chinese literature. But Waley, a “rather crotchety gentleman,” according to Keene,49 declined, telling Keene, “I don’t feel inclined to come in on the anthology business.”50

Keene, however, was enthusiastic about the anthology business. Like Rosset and Allen, he had become interested in East Asian culture from his experiences in World War II. Keene was a Columbia undergraduate studying with Mark Van Doren when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Since he could not imagine himself “charging with a bayonet or dropping bombs from an airplane,” he decided to train as a translator and interpreter at the US Navy Japanese Language School in Boulder, Colorado, after which he honed his language skills as an intelligence officer in the Pacific.51 After the war, he returned to Columbia to pursue graduate study in Japanese literature. He received his PhD in 1949 and taught Japanese literature at Columbia for the next fifty years, founding the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture and retiring only recently as the Columbia University Shincho Professor of Japanese Literature. Over the course of his long and illustrious career, he became one of the world’s most respected scholars and translators of Japanese literature, and one of only three who were not Japanese to receive the title of Bunka Koro-sha (Person of Cultural Merit).

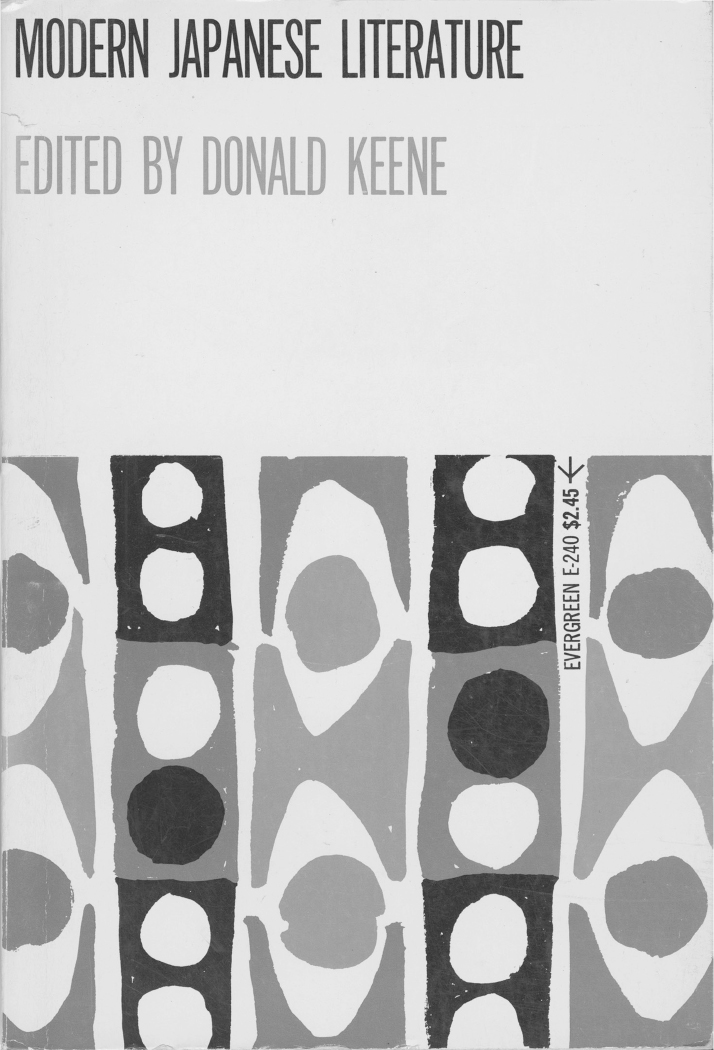

In 1955, Rosset and Keene decided to split the anthology in two: the first volume covered “the earliest era to the mid-nineteenth century,” and the second was devoted to modern Japanese literature of the last century. In the preface to the second volume Keene felt compelled to account for the fact that both anthologies—one covering more than one thousand years; the other, less than eighty—were the same length. According to Keene, the “disproportion is largely to be explained in terms of the amount of literature which has poured from the printing presses in recent times.”52 In the introduction, Keene correlates this groundswell of literary production to the opening of Japan to Western influence, when “Japanese literature moved from idle quips directed at the oddities of the West to Symbolist poetry, from the thousandth-told tale of the gay young blade and the harlots to the complexities of the psychological novel.”53 Keene concludes with the prediction that, “as European traditions are finally absorbed, not only by the novels but by the drama and poetry as well, we can expect that the amazing renaissance of literature in Japan during the past half-century or so will continue to be one of the wonders of the modern literary world.”54 Keene’s correlation of Japanese literary modernity with the absorption of “European traditions” indicates the degree to which the standards of Western modernism informed the developing canon of world literature in the postwar era. As he affirms in his introduction, Japan, like the rest of the world, had learned that “the industrial plant, democracy, economics, Symbolist poetry, and abstract painting all go together.”55 To visually affirm this series of equivalences, Grove used one of Kuhlman’s abstract cover designs for the anthology (Figure 8).

The timing of Grove’s publication of Keene’s anthology was felicitous, as the newly formed Conference on Oriental-Western Literary Relations of the Modern Language Association had been lamenting the absence of affordable translations of Asian literature. In his review of the anthology for the conference’s journal, Literature East and West, Glen Baxter of Harvard called it “the most satisfying anthology of the literature of any Asian country” and noted, in particular, that “thanks to UNESCO support Professor Keene has been in a position to decide what should be translated and then seek especially qualified persons to undertake it.”56 Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, Grove published and distributed numerous translations and studies of Asian literature and culture, frequently in collaboration with UNESCO. In addition to translations by Keene and Waley, Grove published studies of Zen Buddhism, both by Japanese scholars such as Daisetz T. Suzuki and by American popularizers such as Alan Watts. Grove also became the American distributor for the Londonbased Wisdom of the East series, which had been founded in 1904 but received a renewed mandate in the postwar era. As its general editor, J. L. Cranmer-Byng, proclaimed, “Two great wars have done much to alter the map of the world and as a result, Asia is now assuming an important place in international affairs.” Hewing close to the UNESCO mandate, Cranmer-Byng argues that this new situation requires that Westerners develop a familiarity with Asian culture, since “it is only through a sympathetic appreciation of Asia’s cultural inheritance that foreigners will be able to . . . realize how great an extent their religion, philosophy, and poetry and art still mould the outlook of the peoples of Asia today.”57 In the late 1950s Grove also formed the East and West Book Club, offering a choice between The Golden Bowl and The Anthology of Japanese Literature free with a membership.

Figure 8. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for Modern Japanese Literature (1956).

This developing East-West dialogue is abundantly evident in the pages of the Evergreen Review. The first issue to seriously engage Asian culture is volume 2, number 6 (Autumn 1958). Susan Nevelson’s cover photo depicts a young Asian of uncertain gender dressed in black and holding a white dove. The inside cover features a full-page ad for Grove’s lavish production of Ken Domon and Momoo Kitagawa’s study, The Muro-Ji: An Eighth Century Japanese Temple, Its Art and History. And Daisetz T. Suzuki, just finishing a five-year stint as a visiting professor at Columbia University, contributes an essay analyzing the degree to which “Zen has entered internally into every phase of the cultural life of the [Japanese] people.”58 As an illustration, Suzuki offers the “one-corner” style of Japanese painting, characterized by “the least possible number of lines or strokes which go to represent forms.”59 Suzuki sees this style as an instance of the attitude “known as wabi in the dictionary of Japanese cultural terms”; and he explains, “Wabi really means ‘poverty,’ or, negatively, ‘not to be in the fashionable society of the time.’”60

Suzuki’s essay is followed by “Franz Kline Talking,” a transcript of the abstract expressionist painter’s conversation with Frank O’Hara, whose poem “In Memory of My Feelings” is also featured in this issue. O’Hara’s introductory statement triumphantly announces, “The Europeanization of our sensibilities has at last been exorcized as if by magic . . . which allows us as a nation to exist internationally.”61 Kline discusses his “calligraphic style” in an international context, touching on a variety of painters he admires, including Hokusai, whose painting of Mount Fuji reveals how “his mind has been brought to the utter simplification of it.”62 Kline’s monologue is followed by three reproductions of his calligraphic paintings, stark and simple black brushstrokes that clearly complement Suzuki’s discussion of Zen aesthetics.

Gary Snyder’s translation of the “Cold Mountain Poems” follows Kline’s paintings. Though the poet Han-shan (Cold Mountain) was Chinese, Snyder introduces him as “a robe-tattered wind-swept long-haired laughing man holding a scroll” in a sketch featured in a Japanese art exhibit that came to the United States in 1953.63 Snyder concludes, “He and his sidekick Shih-te (Jittoku in Japanese) became great favorites with Zen painters of later days—the scroll, the broom, the wild hair and laughter. They became immortals and you sometimes run into them today in the skidrows, orchards, hobo jungles, and logging camps of America.”64 Jack Kerouac dedicated The Dharma Bums, prominently advertised in this issue of the Evergreen Review, to Han-shan. As Kerouac and Snyder’s presence here indicates, Grove’s vision of an East-West dialogue was heavily inflected by the international interests and itineraries of the Beats.

In 1965, Rosset found a modern Japanese author who realized this Beat vision of world literature: Kenzaburo Oe, who had written a dissertation on John-Paul Sartre and whose favorite book was Huckleberry Finn. Oe was fluent in English, a passionate spokesman for the Japanese New Left, and an avid fan of Henry Miller; his international interests jibed perfectly with Rosset’s. The two had become good friends by the time Oe visited the United States in 1968 to attend a Harvard summer seminar on Huckleberry Finn and Invisible Man and to promote A Personal Matter, which Grove had just published. In its “Authors and Editors” column, Publishers Weekly heralded Oe as “Japan’s first ‘modern’ novelist, one whose literary ancestry is wholly Western.”65 In the flyleaf to A Personal Matter, Grove affirmed Oe as “the first truly modern Japanese writer,” one who had single-handedly “wrenched Japanese literature free of its deeply rooted, inbred tradition and moved it into the mainstream of world literature.”

The semiautobiographical plot of A Personal Matter illustrates the degree to which this vision of world literature was rooted in the geopolitics of the American century. Its hero, Bird, is a disaffected graduate student in English who longs to travel to Africa, but he has recently married and his new wife’s pregnancy promises to put an end to his plans. The novel opens with Bird contemplating a map of Africa in a world atlas:

Africa was in the process of dizzying change that would quickly outdate any map. And since the corrosion that began with Africa would eat away the entire volume, opening the book to the Africa page amounted to advertising the obsoleteness of the rest. What you needed was a map that could never be outdated because political configurations were settled. Would you choose America, then? North America, that is?66

With the noticeable absence of Europe, which was also undergoing somewhat dizzying geographic alteration, Bird’s geopolitical musings conveniently lay out the postwar coordinates onto which Grove would map its vision of world literature: a formerly colonized African continent rapidly resolving into a turbulent mosaic of new nations; an American hemisphere renegotiating the scale and scope of the term “America”; and an “East” whose meaning to the “West” is being reconfigured by the US victory in the Pacific theater of World War II.

On Grove’s publicity questionnaire for authors, in answer to the question, “What is the shortest statement you can make that aptly expresses [your book’s] scope and theme?,” Oe wrote: “The effort of a post-war youth of Japan for the genuine authenticity.”67 In his adolescent wanderlust, Bird bears some resemblance to Sal Paradise, but he diverges considerably in his successful discovery of the “authenticity” that Kerouac’s avatars never fully achieve. After spending the entirety of the narrative in contemplation of abandoning his wife and disabled child to run off to Africa with his old girlfriend, Bird in the end decides to stay in Japan as “a guide for foreign tourists.”68 Instead of introducing himself to the world, he will introduce the world to Japan. In a draft of an essay entitled “How I Am a Japanese Writer,” Oe insists, “If we want to find the authenticity of modern, Japanese literature, we must seek for it in the history of encounters with the occidental world, and especially we must seek for it in the history of encounters in which we Japanese played an active, not a passive, part.”69 Oe’s novel, both in its plot and in its publication, can be understood as the implicit object of such a search. Oe was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994, one of five Grove Press authors to win this imprimatur of global literary reputation.

In the same year that Grove entered into negotiations with Keene over the anthology of Japanese literature, Rosset agreed to be Amos Tutuola’s literary agent in the United States. In the late 1950s Grove published the three texts for which he remains most well known—The Palm-Wine Drinkard, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and The Brave African Huntress—while also exerting considerable effort to get his stories into American magazines. The books met with only modest success, and with the exception of a noteworthy inclusion in an Africa-themed issue of the Atlantic Monthly and a single story in the Chicago Review, American editors rejected Tutuola’s apparently formless surrealistic stories. Rosset himself wrote to Tutuola in 1953, complaining, “Sometimes I think that the endings of your stories are rather weak. They might be more definite. We should know that the story has a beginning, middle and end. Also they (your stories) are sometimes too complicated. You start one story and then bring in another story, and the [reader] gets confused about what happened to the first story.”70

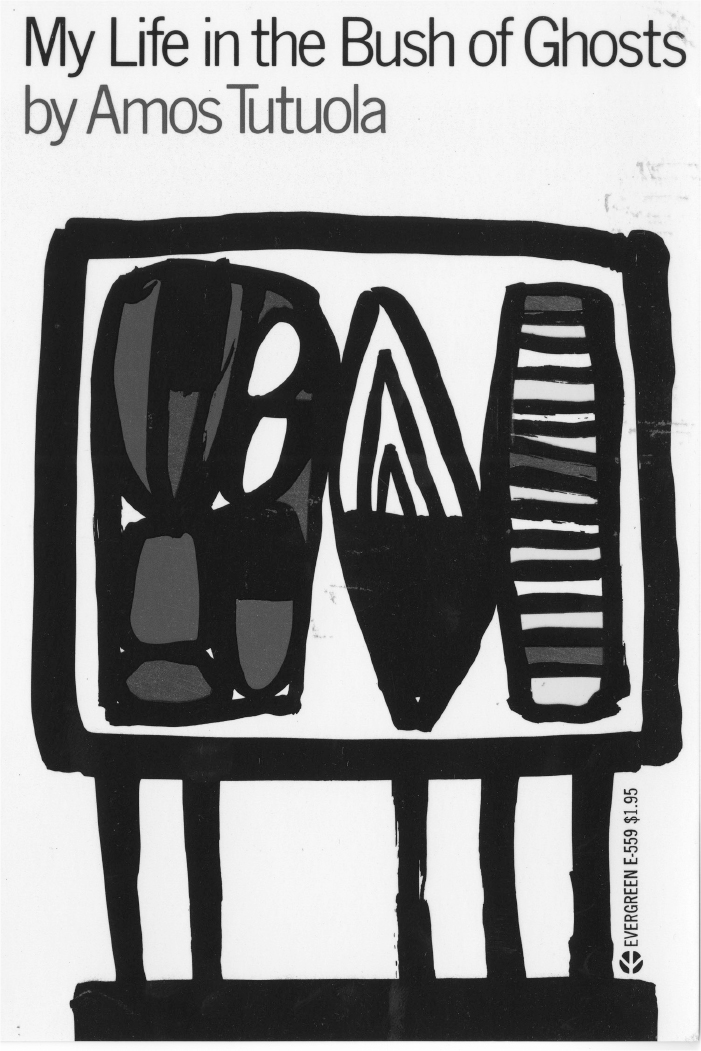

Tutuola was initially understood in the United States as a sort of modernist manqué. As Selden Rodman affirms in his review of The Palm-Wine Drinkard, “If you like Anna Livia Plurabelle, Alice in Wonderland, and the poems of Dylan Thomas, the chances are you will like this novel, though probably not for reasons having anything to do with the author’s intentions.” Rodman adds that “Tutuola is not a revolutionist of the word, not a mathematician, not a surrealist. He is a true primitive.”71 This vision of Tutuola as unconscious modernist was reinforced by Kuhlman’s covers for the Evergreen Original versions of his novels. The cover for My Life in the Bush of Ghosts echoes Kuhlman’s designs for Beckett’s trilogy, assimilating Tutuola’s apparent primitivism to a modernist aesthetic (Figure 9). However, there are figural associations in Kuhlman’s design that anticipate the more nuanced interpretations of Tutuola’s work; the cover clearly references a television screen, commenting on the “Television-Handed Ghostess” who briefly figures in the text.

A more knowledgeable explanation of Tutuola’s syncretism would have to await Grove’s publication of the English translation of Janheinz Jahn’s important study, Muntu: The New African Culture (1961). Jahn, coeditor of Black Orpheus and one of the most influential European scholars of African culture in the postwar era, opens his study with the portentous announcement that “Africa is entering world history.”72 For Jahn, this entry mandates a new approach to the study of African literature. Deprecating earlier efforts to understand African writers in exclusively European terms, Jahn establishes that “the forced classification of neo-African authors into European literary groups . . . has done more harm than good to the understanding of their poetry.” Jahn further affirms that, since African culture has “spread over several European languages,” it is no longer logical to categorize literatures by national language. Once he analytically divorces nation from language, Jahn is able to claim, “Within African literature Tutuola is intelligible; within English literature he is an oddity.”73

Figure 9. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Evergreen edition of

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1954).

In his introduction, Jahn quotes extensively from Frantz Fanon, another important author whom Grove published only a few years later. When Grove published Muntu, Fanon’s Peau noire, masques blancs had not yet been translated into English, but its prominent appearance here reveals the political volatility that roiled the calls for cultural exchange that motivated studies like Jahn’s. Jahn cites Fanon’s text to establish that “there is no universal standard for the evaluation of cultures” and to legitimate his study as an attempt to define and evaluate “neo-African” culture on its own terms.74 By the time Grove published the English translation of Neo-African Literature: A History of Black Writing in 1968, Jahn was explicitly framing this cultural relativism geopolitically:

The end of colonialism does not mean merely redrawing the political maps of Asia and Africa. The independence of the countries outside Europe which were formerly colonies is far from being only a political phenomenon; it tends to find expression in all spheres of life, especially the cultural sphere. If a true partnership is to be reached, the values hitherto centred on Europe need to be reappraised. For each member of a partnership should try to understand every other member on the basis of the fellow-partner’s values—instead of taking his own standards as universally applicable.75

On the one hand, Jahn’s insistence that Europe reappraise its values resonates with the widely shared sense that two world wars had fatally compromised its claims to ethical and political authority and that the literature of postwar Europe, as centrally illustrated by Beckett, affirmed this decline. On the other hand, Jahn’s cultural relativism resonates with the UNESCO mandate, insisting on cultural exchange as a precondition to successful diplomatic relations. By this time, however, UNESCO’s vision was widely seen as hopelessly utopian, and Fanon’s program of regenerative violence had displaced Jahn’s vision of cultural exchange.

In 1961, the year that Grove published Muntu, it also published Octavio Paz’s now-classic study Labyrinth of Solitude, which famously announces, “For the first time, we are contemporaries of all mankind.”76 Paz’s pronouncement echoes Jahn’s claim about Africa entering world history, and he affirms that “Mexico’s situation is no different from that of the majority of countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.”77 This perception of simultaneity was crucial to the very possibility of a truly international modernism; insofar as the conceptual coherence of an avant-garde depends upon a linear model of history, an international avant-garde requires that its constituent nations coexist at the same point on the same time line. This sense of global simultaneity began to emerge during the era of decolonization.

Written mostly in Paris, where Paz worked in the Mexican embassy after the war, and addressed partly to readers in the United States, where he had lived for a time during the war, Labyrinth of Solitude illustrates the coincidence of historical simultaneity and cultural difference that informed Grove’s vision of world literature. In early 1961, Paz wrote to Rosset that US readers might be ready to reach a better understanding of his country as well as the larger geopolitical system within which their relations were transforming:

I really do think this is the most opportune time for publication . . . I have the impression that, since the recent developments in Africa and specially in Cuba, the American people has started to be more conscious of what is called, in the burocratic jargon of our times, “underdevelopped” countries. My book is, in some ways, a portrait of one of those countries, an inquiry made by a native writer (underdeveloped or superdevelopped?).78

Paz was already acquainted with the United States from his tenure as a Guggenheim Fellow at UC Berkeley during the war, and he returned in 1961 at the invitation of the Institute of Contemporary Arts cultural exchange program funded by the Ford Foundation. Paz concedes in his opening chapter, “The Pachuco and Other Extremes,” that many of the arguments he develops in Labyrinth of Solitude originally occurred to him during his stay in the States. Such a cultural context provides an important hemispheric sidelight on Paz’s conclusion that, in the postwar era, “the old plurality of cultures . . . has been replaced by a single civilization and a single future” and that “world history has become everyone’s task, and our own labyrinth is the labyrinth of all mankind.”79

In his preface to the Borzoi Anthology of Latin American Literature, editor Emir Rodríguez Monegal cites Paz’s claim to contemporaneity and dates the boom in Latin American literature to 1961. He chooses this year not because of the US publication of Labyrinth of Solitude but because of another event that also involved Grove Press: the co-awarding of the newly established International Publisher’s Prize to Jorge Luis Borges and Samuel Beckett. As José David Saldivar affirms in The Dialectics of Our America, this simultaneous recognition gave “our American literature . . . its rightful place.”80

It is worth dwelling briefly on the significance of this now defunct prize, which is oddly absent from James English’s otherwise excellent study, The Economy of Prestige. Established by six publishers, Weidenfeld and Nicolson (United Kingdom), Gallimard (France), Einaudi (Italy), Seix Barral (Spain), Rowohlt (Germany), and Grove (United States), the prize was to be given to “an author of any nationality whose existing body of work will, in the view of the jury, be of lasting influence on the development of various national literatures.”81 The publishers themselves established committees that both chose submissions and constituted the jury. The winners were then rewarded with translations into the native languages of the publishers, which by the next year had expanded to eleven. According to Grove’s press release, “The aim of the prize . . . is to provide the largest possible international audience for the winning author.”82 In other words, to win the prize was to be immediately catapulted into the realm of world literature. In his letter inviting Alfred Kazin to be on the selection committee, Rosset ambitiously affirms that the prize is “similar to something like the Nobel Prize, excepting that we hope it will benefit a writer still in his most creative years and bring world attention to someone who is perhaps not known outside his own country.”83

Grove’s committee included Kazin, Donald Allen, William Barrett, Jason Epstein, and Mark Schorer. Although the committee was free to choose any published writer, the top three nominees were Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller, and Jean Genet, all Grove Press authors. According to Rosset’s recollection, the initial voting was split between English- and non-English-speaking committees, which meant that Beckett also had the support of the Weidenfeld committee, which included Angus Wilson and Iris Murdoch. Borges was endorsed by the Einaudi committee, which included Carlo Levi, Alberto Moravia, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Italo Calvino; the Seix Barral committee, which consisted almost entirely of Catalan dissidents, including José Castellet, Juan Petit, and Antonio Vilanova, plus Octavio Paz; and the Gallimard committee, which included Michel Butor, Roger Caillois, Raymond Queneau, Jean Paulhan, and Dominique Aury. As Seaver affirms in his memoirs, “There was a clear division between north and south, the Germanic languages on the one hand and the Romance on the other.”84 Awarding the prize to both Borges and Beckett was a compromise, certainly deserving of the historical significance it’s been granted by historians of the Latin American boom. Insofar as both authors had already been consecrated in Paris, their co-award can be seen as marking that city’s persistence as a cultural capital in a postwar literary landscape increasingly dominated by Anglophone and Hispanophone publishing industries.

Borges himself famously commented, “As a consequence of that prize, my books mushroomed overnight throughout the world.”85 Borges’s work in the postwar era was likewise understood in international terms. As Anthony Kerrigan affirms in his translator’s introduction to the Grove Press edition of Ficciones (1962), the “work of Jorge Luis Borges is a species of international literary metaphor.”86 For Kerrigan, Borges’s encyclopedic knowledge transfers “inherited meanings from Spanish and English, French and German, and sums up a series of analogies, of confrontations, or appositions in other nations’ literatures.”87 Borges’s work, in other words, structurally transcends the national literary traditions based in individual European languages. Borges himself, in an essay included in the New Directions anthology of his work, Labyrinths, which was issued in the same year as Ficciones, deprecated “the idea that a literature must define itself in terms of its national traits” and instead announced that Argentines, like Jews, “can handle all European themes, handle them without superstition, with an irreverence which can have, and already does have, fortunate consequences.”88 But he also recognized the belatedness of this appropriation in its relation to the cosmopolitan modernism on which it piggybacks. In his own prologue to the first section of Ficciones, he satirically laments: “The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a résumé, a commentary.”89 Borges’s proto-postmodern aesthetic self-consciously subordinates itself to high modernism. Instead of writing a new magnum opus, Borges describes imaginary ones that play on the extravagant claims made for those that do exist. In this sense, Ficciones can be further imagined as a series of prefaces—Jason Wilson calls them “essay-cum-short-story-cum-book reviews”—not only to the imaginary texts that they comment upon but to the wave of literary experimentation that they will inspire.90 Furthermore, as librarian and bibliophile, Borges marks an era when world literature can still be understood in terms of the circulation of printed texts.

Borges foregrounds what one might call the paratextual politics of world literature; his short descriptions of much longer works both illustrate and parody the degree to which translated literature tends to mandate prefatory protocols, particularly when geared toward an academic audience. Ben Belitt, who translated the work of Federico García Lorca and Pablo Neruda for Grove, acknowledged as much when he collected his translator’s prefaces into a book entitled Adam’s Dream: A Preface to Translation, published by Grove in 1978. Donald Allen had solicited Belitt as a possible translator for Lorca’s Poet in New York in 1952, and Belitt responded favorably, noting “the impressive record that your imprint has created for itself in its initial publishing commitments. It seems to me your combination of fastidious choice and public usefulness is already a unique one.”91 In the transcribed “conversation” with Edwin Honig that makes up the opening chapter of Adam’s Dream, Belitt credits Allen with the “uncanny facility of sensing what are generally called ‘vogues’ or waves in the making, and later turn out to be total landslides of taste.”92 Belitt backdates the beginnings of the Latin American boom to his bilingual edition of Lorca’s modern poetic sequence of surrealist impressions written during the poet’s brief visit to the East Coast during the Depression. In his translator’s foreword, reprinted in Adam’s Dream, Belitt affirms that “it was to American readers in the broadest sense of the term . . . that the poem was initially addressed by its publishers in Mexico, Argentina, and New York . . . Today, A Poet in New York remains an indispensable book for readers of the two Americas.”93 The positioning of this text by a Spanish poet in the hemispheric context of the “two Americas” was reinforced by the frequent critical references to the influence of Walt Whitman, to whom Lorca dedicates an ode late in the sequence, and to the possible influence on Allen Ginsberg, whose “Howl” it arguably anticipates. The initial printing of A Poet in New York sold more than thirty-five thousand copies.

Belitt’s major achievement for Grove during these years was a sequence of anthologies of the poetry of Pablo Neruda, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1971 and whom Rodríguez Monegal introduces as “the greatest Latin American poet since Rubén Darío.”94 Neruda’s itinerant career and international reputation undoubtedly helped realign the meanings of “America” in the postwar era. As with Lorca, this realignment ran through Whitman, to whose work Neruda’s was frequently compared. In his translator’s foreword to Selected Poems, the first of four Neruda collections he assembled for Grove, Belitt affirms that Neruda’s vision is “like Whitman’s” and further elaborates that the poet’s ambitious Canto general (General Song) is, “like Moby Dick and Leaves of Grass—whose cadences should convey it to American ears—a progress: a total book which enacts a total sensibility.”95 In the introduction to his collection of critical prefaces, Belitt clarifies how this hemispheric sensibility trumps and transcends the discourse of “three worlds” that dominated the 1960s, offering instead a cosmopolitan vision of “the literature of one world and a single community of tradition, rather than a symptomatic ‘third’ of it.”96 Grove organized a big party at its downtown offices for Neruda, an early hero of Rosset’s, when he came to New York to attend the International Progressive Education Network (PEN) conference in 1966, the year in which he also received a citation as an Honorary Fellow of the Modern Language Association. At a well-attended reading at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association’s (YMHA) Poetry Center, his first in the United States, Archibald MacLeish emphatically introduced Neruda as “an American poet,” while Selden Rodman titled his review of the reading for the New York Times “All American.”97

Neruda’s international significance was enhanced by his global itinerary. During his years as a Chilean diplomat, Neruda lived first in Rangoon, Java, Ceylon, and Singapore, after which followed posts in Buenos Aires, Barcelona, Madrid, and Mexico City. After the war, he was briefly a Communist Party senator in Chile, but when the party was outlawed in 1948, he went into exile. He spent the next four years traveling across Europe, Asia, and the Soviet Union, returning to Chile in 1952, where he remained until his death in 1973. By the time Neruda’s poetry became popular in the United States, he was already a figure of considerable international stature and experience. The titles of his two major poetic sequences—Residence on Earth and General Song—reflect the global scope of his life and reinforce the correlation between political and poetic diplomacy that coincided closely with the international vision of Grove Press.

Grove’s decision to publish bilingual editions of Spanish-language poetry translated by North American poets (it also issued a bilingual edition of the Peruvian poet Cesar Vallejo’s Poemas humanos, translated by Clayton Eshleman) projected in material and textual form some of the complexities of a hemispheric literary field divided by both language and geopolitics. Belitt asserts that, in bilingual translations, “the binder’s seam is there to remind us that the translation of poetry is not a systematic plagiarism of the original, under cover of a second language: it is an act of imagination forced upon one by the impossibility of the literal transference or coincidence of two languages, two minds, and two identities, and by the autonomy of the poetic process.”98 For Belitt, this autonomy should be granted to both the original and the translation. Thus, he wrote to Rosset, regarding his translations of Lorca, “I would like to make it clear that the English text is a creative undertaking whose authorship is attributable to me in the same sense that ‘my own’ poems are attributable to me.”99 The “binder’s seam,” then, becomes a highly complex site of mediations and separations. It both marks and bridges the division between languages, affirming the impossibility of literal translation while simultaneously enabling the autonomy of literary translation. It also, significantly, allows Belitt to lay claim to the English translations without occluding the integrity of the Spanish originals.

This tension between autonomy and appropriation is abundantly evident in the special issue of the Evergreen Review published in the winter of 1959, “The Eye of Mexico.” Donald Allen had originally arranged with Paz to be guest editor, but after he had selected the contributors, Paz became too busy and recommended Ramón Xirau of the Centro mexicano de escritores to take over. Xirau was in fact from Barcelona but had migrated to Mexico after the Spanish Civil War. He had studied in Paris and lectured in the United States under the auspices of the Rockefeller Foundation, which had also provided the initial funding for the Centro, originally established by the American novelist Margaret Shedd. Xirau became subdirector and editor of its bimonthly Englishlanguage bulletin. In addition to issuing the newsletter, the Centro provided fellowships to Mexican and US writers, as well as labor and subvention for translations between Spanish- and English-language literature.

“The Eye of Mexico” opens with an excerpt from Labyrinth of Solitude and includes prose by Juan Rulfo and Carlos Fuentes, poetry by Jaime Sabines and Manuel Durán, paintings by José Luis Cuevas and Juan Soriano, and an essay by anthropologist Miguel León-Portilla, “A Náhuatl Concept of Art.” The poetry is translated by Paul Blackburn, Lysander Kemp, Denise Levertov, and William Carlos Williams, who, like Belitt, were “more concerned with re-creation in English than with completely literal translation.”100 The Spanish originals are not included. The issue also provides a directory of Mexican bookstores and art galleries, ads for Mexican restaurants in Manhattan, and a back-cover ad for Aeronaves de México. Grove arranged for a front-window display in the Aeronaves offices, located at the heavily trafficked corner of 5th Avenue and 42nd Street, featuring artwork by Cuevas and Soriano and a blow-up of the journal’s cover. Aeronaves agreed to fly a small group of Mexican authors and artists to New York for a cocktail party in their offices celebrating the issue, and Grove offered issues in quantity at cost for the airline to distribute on its flights. According to Publishers Weekly, Grove sold out its initial printing of twenty thousand in less than a month.

The contents of the “Eye of Mexico” issue are framed by articles and reviews that place it in a more complicated global frame. It opens with “The Continuing Position of India,” a long piece by Anand (Arthur) Lall, India’s ambassador to the United Nations. Lall was one of the judges in Grove’s Indian literature contest and had become friendly with Rosset, who agreed to insert this piece into the Mexican issue at the last minute. This “special statement on India’s foreign policy” defending Nehru’s position of nonalignment begins before and ends after the contents of the special issue, inevitably reminding readers of the larger Cold War context within which this hemispheric dialogue is taking place. More specifically, it emphasizes the degree to which Cold War–era cultural exchange would be facilitated by diplomatic figures such as Lall and Paz, who was Mexico’s ambassador to India from 1962 to 1968. Paz then resigned from the diplomatic service in opposition to Mexico’s suppression of the student protests in Tlatelolco, which he wrote about in The Other Mexico, also published by Grove. By then, the rhetoric of cultural exchange that Grove promoted in the late 1950s and early 1960s had been supplanted by a rhetoric, and practice, of political revolution.

The special-issue contents of “The Eye of Mexico” are followed by a section of news and reviews. One of the texts reviewed is Paz’s Anthology of Mexican Poetry, which, as reviewer James Schuyler notes, was “published by agreement between Unesco and the Government of Mexico.”101 This volume, initially issued by Indiana University Press and then reprinted by Grove in 1985, features a preface by C. M. Bowra that, the flyleaf affirms, is intended “to emphasize the essential solidarity of creative artists in different nations, language, centuries, and latitudes, and to point out the fundamental identity of emotions to which the genius of the poet can give a form at once lasting and beautiful.” But Schuyler is less interested in Bowra’s “official bull” or Paz’s “informing” introduction than he is in the task of the translator, Samuel Beckett, whose labors he lauds as “a Horowitz performance of gift and skill.”102

Beckett haunts “The Eye of Mexico,” as Schuyler’s brief appraisal of what S. E. Gontarski calls “the single most neglected work in the Beckett canon” is followed by Richard Howard’s translation of Maurice Blanchot’s landmark review of Beckett’s trilogy, “Where Now? Who Now?”103 In this somewhat unexpected New World context, Blanchot’s review creates a felicitous apposition between Beckett’s masterwork and the final lines of Paz’s excerpted chapter: “The Mexican does not transcend his solitude. On the contrary, he locks himself up in it. We live in our solitude like Philoctetes on his island, fearing rather than hoping to return to the world. We cannot bear the presence of our companions. We hide within ourselves . . . and the solitude in which we suffer has no reference either to a redeemer or a creator.”104 Beckett’s narrator can figure both as a reduction of Paz’s solitude to its purest generic state—and indeed, Beckett’s trilogy was frequently framed in precisely these “universal” terms—but also as a specification of the writer’s predicament in the twilight of modernism.

If, in the postwar European context, this predicament solicited the strained silences and solitudes of Beckett’s austere universe, in the New World context late modernist exhaustion blossomed by a sort of dazzling dialectical reversal into an explosion of aesthetic opportunities, abundantly illustrated by Donald Allen’s landmark anthology The New American Poetry, issued by Grove in 1960. I conclude with this foray into a more conventionally organized anthology in order to point out the degree to which the project of postwar American literature was implicated in and inflected by the global literary field illustrated by Grove’s international title list. Most of the poets included in the volume, which was the first to lay out for a popular readership the now canonical—and significantly geographical—designations of the Black Mountain College, the San Francisco Renaissance, and the New York school, appeared as well in the pages of the Evergreen Review, frequently as both translators and poets. While the exclusive US origins of the poets included in the volume itself seem almost blithely to disregard the hemispheric model endorsed by Grove’s simultaneous investment in Spanish-language literature, the international scope of Allen’s projects for Grove during these years dictates that we grant some dialectical nuance to its contents.

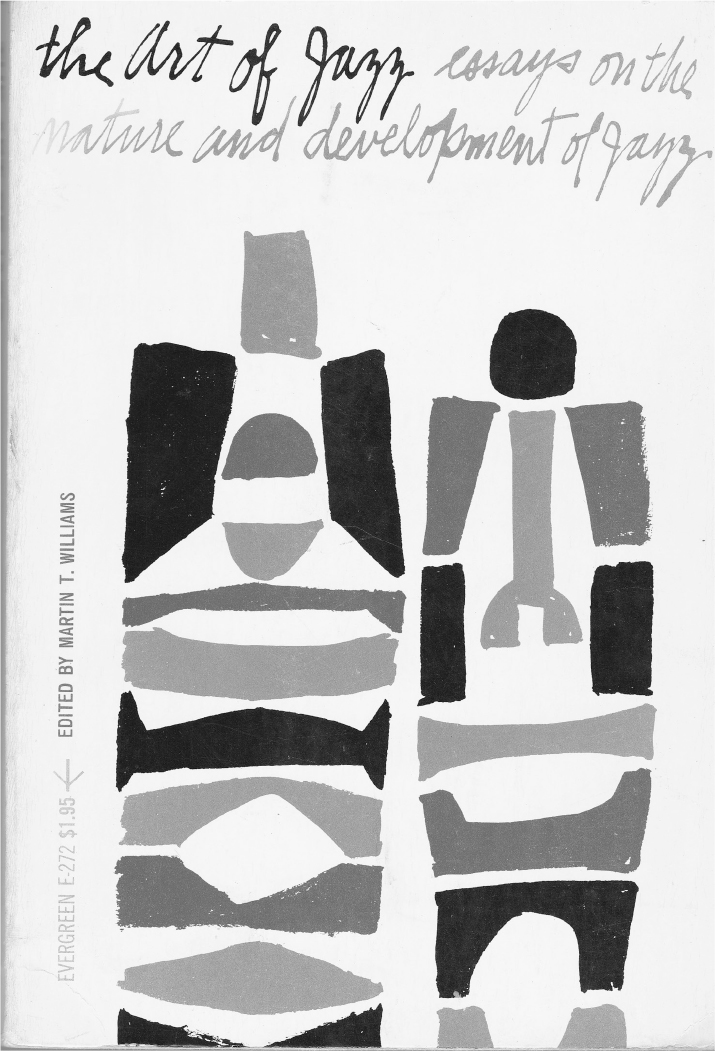

Figure 10. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for The Art of Jazz (1959).

Allen calls the poets in his anthology “our avant-garde, the true continuers of the modern movement in American poetry” and further claims that “through their work many are closely allied to modern jazz and abstract expressionist painting, today recognized throughout the world to be America’s greatest achievement in contemporary culture.”105 In this same period Grove published a number of pioneering studies of American jazz, including translations of André Hodeir’s foundational Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence (1956) and Toward Jazz (1962), as well as important anthologies edited by Nat Hentoff, Albert McCarthy, and Martin Williams, who also wrote a regular column on jazz for the Evergreen Review. These titles, all heavily promoted in quality-paperback format, feature some of Kuhlman’s most characteristically abstract expressionist covers (Figure 10), evoking his designs for both Beckett and Tutuola. Allen’s goal for his anthology was to make “the same claim for the new American poetry, now becoming the dominant movement in the second phase of our twentieth-century literature and already exerting a strong influence abroad.”106 Allen places his anthology within the late modernist matrix, offering his cross section of postwar poets as an American contribution to an international scene. And it was a huge success; as Rosset affirms in an unpublished interview, “That book became the standard, the landmark book, and it sold and sold. It taught poetry to a whole generation of young kids.”107