|

Publishing Off Broadway |

|

Publishing Off Broadway |

The early performances of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot are landmarks in the history of modern theater. Roger Blin’s succès de scandale at the Théatre Babylone in Paris on January 5, 1953; Alan Schneider’s debacle at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami on January 3, 1956 (billed as “the laugh sensation of two continents,” and starring Tom Ewell and Bert Lahr, the play confounded the audience, who came expecting a light comedy); Herbert Blau’s triumph at San Quentin on April 19, 1957: all have become legendary events that anchor any study of Beckett’s dramatic work.1 Much less has been written about an equally significant event in the history of this epoch-defining play: Grove Press’s publication of a one-dollar Evergreen paperback edition in 1956. Spurred by the play’s Broadway debut, when it was sold in the lobby of the John Golden Theater, it eventually sold more than two million copies, becoming an iconic American paperback and one of the bestselling plays of all time.

W. B. Worthen, one of the few critics who has considered the significance of plays as printed texts, affirms that “Beckett’s plays are an essential part of the modern drama’s seizure of the page,” particularly because Beckett’s authority over permissions to perform them was exercised with such high modernist imperiousness and exactitude.2 The authority of the printed play in Beckett’s case anchors the authority of the auteur as source and adjudicator of the conditions and conventions under which the play can be performed. As a profoundly literary figure, in many ways the last modernist genius, Beckett has been a crucial model for the authority of the modern playwright as writer, as producer of the printed text that determines the parameters of performance.

Nevertheless, as Worthen concedes, “Theatre is particularly inimical to print, as print culture tends to derogate both manuscript and oral forms of transmission as lapses from the ideal, transparent, neutrality of mechanical reproduction.”3 This resistance to print was particularly true of the so-called theater of the absurd, whose postwar ascendance dates to the debut of Godot, influenced as it was by the antiliterary theories of Antonin Artaud. Artaud, whose international influence and reputation expanded considerably with the publication of Grove’s English translation of The Theater and Its Double in 1958, famously decried “the idolatry of fixed masterpieces which is one of the aspects of bourgeois conformism,” proclaiming that “it is in the light of magic and sorcery that the mise en scène must be considered, not as the reflection of the written text.”4 Artaud was also instrumental in replacing the authority of the playwright with that of the director, whom he saw becoming “a kind of manager of magic, a master of sacred ceremonies.”5

As James Harding affirms in the introduction to his important anthology Contours of the Avant-Garde, “The theatrical avant-garde has consistently defined itself vis-à-vis a negation not only of the text and mimesis but also of author-ship and author-ity and of . . . academic institutions” more generally.6 Artaud, unsurprisingly, is a recurrent and representative figure in Harding’s collection, which emerged as a response to Bonnie Marranca’s critique of the text-centered curriculum in academic theater studies, “Theatre at the University at the End of the Twentieth Century,” published in Performing Arts Journal in 1995. The essays in Harding’s anthology illustrate the degree to which debates over avant-garde theater tend to adopt Artaud’s opposition between print and performance, an opposition that, in turn, maps onto the tension between playwright and director. In this chapter, I focus instead on the relationship between publisher and reader, a relationship that presents the printed text in complementary, rather than antagonistic, relation to live performance. As a publisher, Grove worked to market printed plays as supplements to performance for those who could attend one, and as substitutes for performance for those who couldn’t. Its texts were designed, as much as possible, to invoke the experience of seeing the play live, frequently in direct reference to specific performances. Its success in this endeavor was crucial to the reception and interpretation of avant-garde drama in the postwar United States.

Grove’s achievement as a publisher of experimental drama complicates Julie Stone Peters’s groundbreaking history of the relations between print and performance in European theater prior to the twentieth century, which concludes with a brief discussion of Krapp’s Last Tape. Peters argues that in the twentieth century, attention shifted from “the difference between the presence of live spectators and the remoteness and privacy of the reader in the study” to “the theatre’s place, on the one hand, in the industry of mass spectatorship and, on the other, in a culture in which one’s most intimate relationship might be, in the end, with a machine.”7 But Grove’s marketing and design of avantgarde scripts reveal that the dialectic between public performance and private reading extended well into the twentieth century. Postwar experimental theater positioned itself in stark opposition to the culture industries and, Beckett’s experiments with radio and tape recording notwithstanding, remained philosophically and politically committed to liveness, especially in the happenings and street theater of the 1960s. Furthermore, the conceptual difficulties of much avant-garde theater were commonly elucidated by American academics in terms of modernist literary technique, mandating that such plays be read as a necessary supplement to seeing them live, and the popularity of experimental theater on college campuses created a large audience for these scripts. As the exclusive publisher of Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Harold Pinter, Kobo Abe, John Arden, Fernando Arrabal, Brendan Behan, Ugo Betti, Freidrich Durrenmatt, Jean Genet, David Mamet, Slawomir Mrozek, Joe Orton, Sam Shepard, Boris Vian, and many others, Grove cornered this market, in the process acquiring an identity as the “off Broadway of publishing houses.”

Grove’s connections to off-Broadway theater were enhanced by its downtown location, close to the Cherry Lane, Village Gate, St. Mark’s Playhouse, and Living Theatre. In 1967, Grove also began producing off-Broadway playbills after Showcard, the company that usually designed them, refused to print one for MacBird!, Barbara Garson’s Shakespearean parody of the Johnson and Kennedy administrations. In that same year, Rosset acquired a theater at 53 East 11th Street. Although it eventually became mainly a venue for screening experimental film, the Evergreen Theater made history with the triumphant New York debut of Michael McClure’s The Beard, which had been shut down for obscenity in San Francisco. Finally, starting in 1968, the Evergreen Review began regularly publishing essays and theater reviews by John Lahr, whose father, Bert Lahr, had famously played Estragon in the American debut of Waiting for Godot and who was already an influential new voice in modern theater criticism. Up against the Fourth Wall: Essays on Modern Theater, a collection of the groundbreaking work he wrote for the magazine, was printed as an Evergreen Original in 1970.

The Evergreen Originals imprint was foundational for Grove’s identity as a publisher of avant-garde drama, and its printed plays had a far more lasting impact than its direct forays into the downtown theater scene. Though it was initially developed as a format for original fiction, Grove quickly adapted it to include original drama as well, as the May 8, 1960, ad in the New York Times Book Review, “Off Broadway’s Most Sensational Hits—in Book Form,” makes abundantly clear. The titles listed include Jack Gelber’s The Connection, Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, Genet’s The Balcony, and Ionesco’s Four Plays. In the ad, Grove calls these “the plays that are making theater history” and encourages readers to “discover their meaning as well as their excitement by reading them for yourself, in EVERGREEN ORIGINAL PAPERBACKS.” Grove adapted this imprint to present avant-garde theater as a specifically literary, and resolutely international, genre that needed to be read in order to be fully understood.

Grove was assisted in this task by a stable of academic critics who, while maintaining an investment in performance, emphasized the “literary” qualities of contemporary drama. Wallace Fowlie, the Harvard-educated professor of French who taught at Bennington, Chicago, Yale, and the New School before spending most of his career at Duke University, encouraged Rosset to publish Beckett in the early 1950s; in his influential study of postwar French drama, Dionysus in Paris, Fowlie heralded the arrival in France of a “new type of supremely literary playwright.”8 Martin Esslin, the English theater critic whose work as a producer for the BBC in the 1960s was centrally responsible for popularizing experimental drama (and who eventually settled at Stanford University), emphasized in his classic study The Theatre of the Absurd that the plays in this “school,” whose name he coined, are “analogous to a Symbolist or Imagist poem.”9

Academics such as Fowlie, Esslin, Richard Coe, Ruby Cohn, Eric Bentley, and Roger Shattuck, all of whom worked with Grove over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, helped chart this genealogy from the modernist literature of the first half of the twentieth century to the experimental theater of the second half, thereby establishing the literary antecedents of the theater of the absurd for the English-speaking world. Coe wrote monographs on Beckett, Ionesco, and Genet, all of which Grove published in the 1960s; Cohn wrote one of the earliest dissertations on Beckett in 1959 and edited Grove’s Casebook on “Waiting for Godot” in 1967. Bentley was responsible for the American reception of Bertolt Brecht and became the general editor of the Grove Press edition of his plays, issued over the course of the 1960s. Shattuck’s The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I, originally published in 1955, became a standard reference on the origins of the French avant-garde; he was guest editor of an early issue of the Evergreen Review on ’pataphysics in 1960 as well as coeditor of Grove’s Selected Works of Alfred Jarry in 1965.

In their biographically oriented studies, these critics frequently emphasized poetry as an apprenticeship to drama, positioning the early poems of these dramatists as crucial to an appreciation of their later plays. Furthermore, by establishing an analogy between experimental theater and modernist poetry, they affirmed the necessity of reading both the plays themselves and their own commentary in order to understand fully the significance of these difficult texts.

. . .

Rosset knew that Grove would have to market these plays as literary texts, and from the beginning he thought of Waiting for Godot as a book. He convinced Beckett not to publish the first act in Merlin, arguing that “EN ATTENDANT GODOT should burst upon us as an entity in my opinion.”10 On the same day, Rosset wrote to Alexander Trocchi, affirming that he would like to see “the play first appear in its entirety in a handsome book.”11 A few months later, Rosset described the book he envisioned to Jerome Lindon: “Our edition will include the play GODOT, plus a page or two of biographical material at the back of the book—as well as photographs of the production (assuming we can obtain them). The book’s jacket will also tell about Beckett and will also contain his photograph, along with quotations from French reviews of his work.” And he affirmed that “we have decided to go ahead with publication of GODOT regardless of the status of the play’s production here.”12

Initial sales of the cloth edition were, unsurprisingly, modest; according to Rosset’s recollections Grove printed one thousand copies and sold about four hundred in the first year, one of which ended up in the hands of actor Bert Lahr, delivered by messenger from the offices of producer Michael Myerberg. Lahr was befuddled by the play, asking his son, the future drama critic, “You’re a student—what does it mean?”13 Lahr eventually accepted the role, and the name recognition he brought to the play helped promote the paperback Grove published in 1956, the year of the play’s debut in the United States. After the famous failure in Miami, Rosset wrote to reassure Beckett: “Certainly all is not lost—the printing of the inexpensive edition forges ahead.”14 And Beckett was on board from the beginning, writing to Rosset, “By all means a paper bound edition, I am all for cheaper books.”15

Meanwhile, in the New York Times, Myerberg made a public appeal for seventy thousand intellectuals to come see the play in order to avoid a repeat of the Miami debacle. Not only did Myerberg agree to sell the cheap paperback in the lobby of the theater but he also arranged for symposiums to be held with the actors during the Broadway run. Later that year, Myerberg wrote to Beckett to report on the success of these discussions:

Of particular interest were the four symposiums we held during the run. They were extremely well attended and displayed a keen interest in the play. A rather startling development here is that four-fifths of our audience are young—under 24, and even boys and girls 17 and 18 are storming the box office for the cheaper seats. At no time have we had cheap seats available at a performance. The youngsters had a complete and ready acceptance of the play, and quite a lot to say about its meaning, which seemed clear to them and had entered into their lives intellectually and emotionally.16

Grove tapped into this youthful and impecunious audience over the next two decades, in the process making Waiting for Godot one of its bestselling paperbacks. Grove also helped to domesticate the notion of the “absurd,” which had begun as a pointedly pessimistic response on the part of European artists and intellectuals to the cataclysmic devastation of World War II but, spurred by the ubiquitous existentialism of John-Paul Sartre and the proliferating scholarship of American academics, developed in the 1960s into a more affirmative ethical orientation, with Beckett as its figurehead.

Rosset realized early on that the college-student audience would be central to Godot’s success, and he convinced Dramatists Play Service to reduce the royalty rate for amateur productions: “We are in close contact with the potential audiences for the play and we know that they consist in the main of university students who may well not be able to afford more than a minimum royalty . . . The whole successful history of this play is the strongest evidence of the necessity for allowing it to be played before very small groups who may also have very limited means.”17 Grove aggressively marketed the paperback edition of the play to these “very small groups,” offering them on consignment to student productions and to every bookstore at any college or university where the play was being performed. And it was performed extensively across the country, as Henry Sommerville affirms: “Between 1956 and 1969, amateur performances of Waiting for Godot were given in every state except Arkansas and Alaska. On average, during each of these years, the play was performed by North American amateurs in thirty-three cities spread across 18 states and one Canadian province.”18

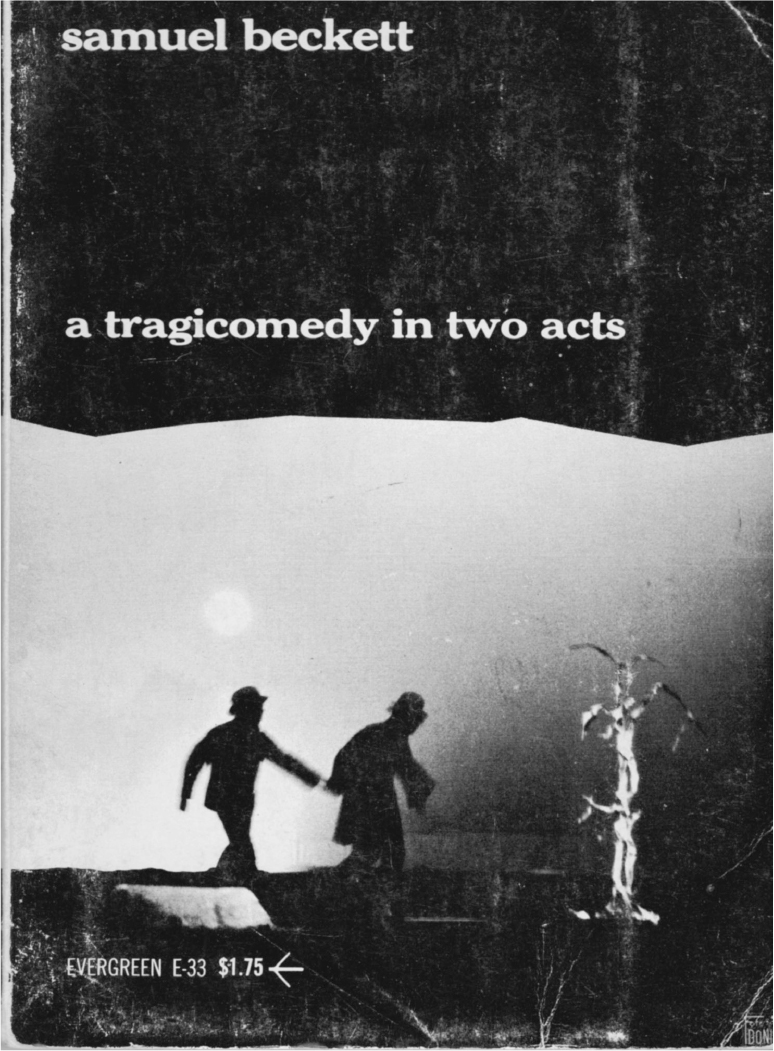

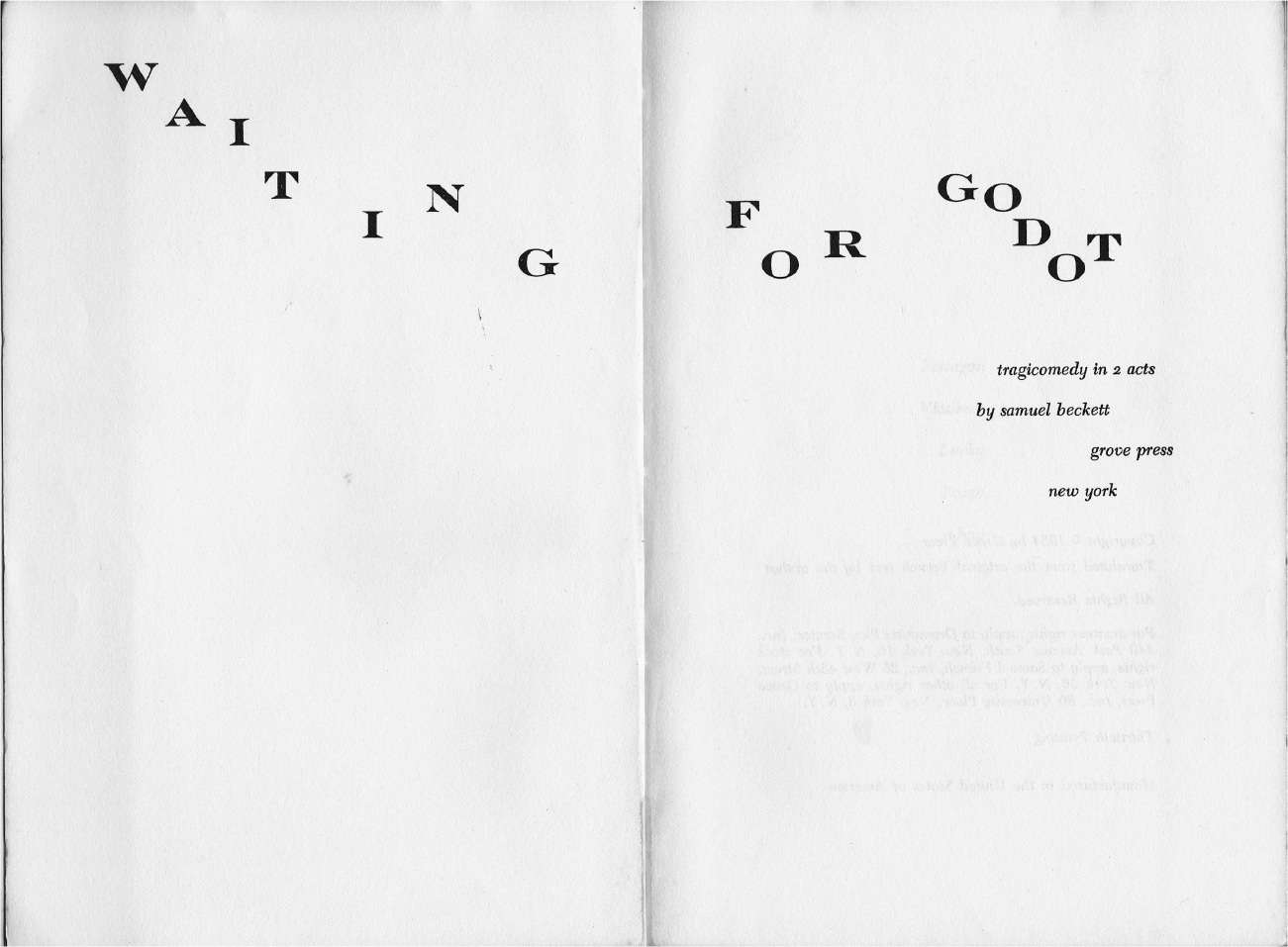

The design of the Evergreen paperback of Waiting for Godot is clearly intended to match in austerity and simplicity the meager decor of its initial production in Paris, the cast and credits for which are listed following the text of the play. The cover photo, selected by Beckett himself, depicts in black and white the heavily backlit silhouettes of Vladimir and Estragon, their hands barely touching, strolling toward the spindly tree that stands to the right. The title and author’s name, all lowercase, run across the top in simple white type against a black background (Figure 11). Inside the book, ample use is made of white space to further emphasize the sparse environment in which the play’s characters find themselves. The title, now in all caps, is spread over the initial recto and verso pages, unevenly spaced both horizontally and vertically, as if the text itself were aimlessly wandering. On the verso page, all in lowercase italics, unjustified, are four lines—“tragicomedy in 2 acts / by samuel beckett / grove press / new york”—resolutely if modestly linking publisher to author and text (Figure 12). On the next recto page the names of the cast are listed, centered vertically and horizontally. Across the top of the following recto page, unevenly spaced like the title, runs the announcement of “ACT I,” below which, left justified, we see the simple setting: “A country road. A tree. / Evening.” In the text of the play that follows, only the verso pages are numbered sequentially in bold black type, as if it is the space across recto and verso, rather than the individual pages, that is being read through. The dialogue is left justified to the immediate right of the speech prefixes, expanding the amount of white space on the page, and foregrounding the alternation of speakers while simultaneously alienating them from their speech, which appears as an autonomous centered column (Beckett insisted on using the speakers’ full names, since “their repetition, even when corresponding speech amounts to no more than a syllable, has its function in the sense that it reinforces the repetitive text”).19 The back cover features an austere photo of Beckett, the left side of his face almost entirely in shadow, accompanied by laudatory reviews of the play and a brief blurb ranking him with Kafka and Joyce.

While it anticipates the design Grove used for Beckett’s other plays, Waiting for Godot came out before Grove launched the Evergreen Originals imprint; the first Evergreen Original Beckett play was Endgame. The cover photo, from Roger Blin’s production, is an uncompromisingly bleak black-and-white shot of Hamm in his chair against a black background, the handkerchief over his face bleached to bright white with the bloodstains in the center vaguely coalescing into an expressionless skull-like face. The text of Endgame is far more compressed than that of Godot, with the italicized stage directions considerably smaller in point size than the dialogue, which wraps around the speech prefixes. The text, then, gives a sense of the claustrophobic interior in which the action of the play unfolds.

Figure 11. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Evergreen paperback of Waiting for Godot (1954).

Figure 12. Frontispiece for the Evergreen paperback of Waiting for Godot (1954).

Grove complemented these efforts to re-create typographically a sense of the play’s setting and mood with a campaign to convince audiences that it was necessary to read it. Initially, Grove capitalized on the befuddlement of critics by claiming that reading the play could clarify its meaning, promoting it as “the play the critics didn’t understand” and encouraging audiences to “read it before you see it,” which became a tagline in the campaign for this and other plays.20

Grove attributed both the difficulty of the play and the necessity of reading it to the poetic quality of Beckett’s dialogue. The back cover of Endgame features a lengthy blurb by Harold Hobson of the Sunday Times, emphasizing that “Mr. Beckett is a poet: and the business of the poet is not to clarify but to suggest; to employ words with auras of association, with a reaching out toward a vision, a probing down into an emotion, beyond the compass of explicit definition.” When Grove distributed Endgame through the Readers’ Subscription, the scholar Vivian Mercier used this designation of Beckett as poet in an essay included in the catalog, “How to Read Endgame.” The play was sold along with a recording of its performance, and Mercer urged readers to listen to it first, because “I want you to experience the play before you interpret it. Listen to what the play is before you start asking yourself what it means; that is what the practiced reader always does with poetry, and Samuel Beckett remains a poet whatever he is writing.”21

Many readers wanted help in becoming “practiced” and wrote to Grove in droves asking myriad questions about the larger significance of these plays. Beckett, of course, was notoriously reticent about the meaning of his work, so Grove responded to the queries with a boilerplate letter that suggested resources that would become central to interpreting the play. The letter began in this way: “Mr. Beckett prefers not to discuss his work. If you would like some help in understanding Mr. Beckett’s work, you might refer to any number of critical works that have appeared.”22 The letter also frequently noted that “Grove Press publishes a short book on Beckett, entitled samuel beckett, by Richard Coe, which sells for 95 cents.” Grove published Coe’s book in 1964, Hugh Kenner’s first book on Beckett in 1961, and Ruby Cohn’s Casebook on “Waiting for Godot” in 1967, along with a series of critical studies of Beckett, Ionesco, Genet, and others over the course of the decade.

The academic industry that rapidly grew around Beckett’s work amply compensated for his silence, and Grove published many of the key critical texts that helped frame his significance for his American audience. This industry ensured that Beckett would early become a staple in college courses, not only in English but also in religious studies and philosophy departments. Grove marketed aggressively to this academic audience, going so far as to propose courses on Beckett and the theater of the absurd consisting entirely of Evergreen paperbacks. By this time, responsibility for the college catalog was in the hands of exunion organizer and Monthly Review contributor Jules Geller, who explained his plans to Donald Allen in October 1967: “Rather than plan the publishing of ‘textbooks’—an obscene form of book publishing as it’s commonly practiced—I am working on fitting our Evergreen and some Black Cat books in groups for certain courses, and promoting them in these groups as a more modern and more interesting way to teach a given subject. This is working out very well.”23

Cohn’s Casebook, which Grove recommended along with Coe’s monograph, Alec Reid’s All I Can Manage, More Than I Could: An Approach to the Plays of Samuel Beckett (1969), and Michael Robinson’s The Long Sonata of the Dead: A Study of Samuel Beckett (1969) for a course entitled “The Vision of Samuel Beckett,” conveniently illustrates the process whereby the initial performance contexts of the play and its controversial reception were assimilated into the readerly practice of academic interpretation. Cohn’s introduction begins by affirming that “Waiting for Godot has been performed in little theaters and large theaters, by amateurs and professionals, on radio and television,” but she quickly shifts to the claim that “Waiting for Godot has sold nearly 50,000 copies in the original French, and nearly 350,000 in Beckett’s own English translation.” She warns that these numbers “help you to know the best-seller, the smash hit, but only the individual can know a classic which is a work that provides continuous growth for the individual,” grounding the value of the play in a resolutely literary and readerly register. She concludes her opening paragraph: “Paradoxically for our time, Waiting for Godot is a classic that sells well,” implicitly recognizing the Evergreen paperback as the embodiment of the play’s success.24 The structure of the anthology then replicates this trajectory, starting with the section “Impact,” which excerpts reviews and accounts of early performances, and concluding with “Interpretation,” which excerpts the type of academic analysis, much of it published by Grove Press, that crucially depends on the printed text. The course itself places Beckett in the company of Proust, Joyce, Kafka, and Sartre; in addition to Waiting for Godot, Endgame, and the trilogy, it includes Beckett’s early study of Proust, which had already become a common resource for academic interpretation of Beckett’s work. Grove’s course proposal, then, attests to its crucial role in enabling the initial development of the academic industry that quickly emerged around Beckett’s work and to the way this industry reciprocally helped Grove establish Waiting for Godot as required reading across the college curriculum.

Waiting for Godot and Endgame also appear in Grove’s 1970 college catalog on the syllabus for a more eclectic course proposal called “The Absurd as Reality.” The other playwright included in this course is Eugène Ionesco, and Grove’s marketing of his plays provides additional insight into how Grove translated drama whose performance conventions were inimical to print into bestselling Evergreen Originals. Ionesco’s plays are much busier than Beckett’s, involving elaborate and frequently cluttered sets as well as bizarre costumes and makeup, so Grove couldn’t take the minimalist approach that worked with Beckett. Furthermore, unlike Beckett, Ionesco was generous with his opinions about his work specifically and contemporary drama more generally, so Grove had the opportunity to present the playwright’s views more directly to the American public.

The strategy of marketing the printed text in conjunction with student performances was replicated with Ionesco, whose plays were also popular on college campuses. During initial negotiations with Gallimard in 1958, Rosset explained the success of this arrangement regarding Godot: “At this time, we have sold 30,000 copies of Samuel Beckett’s WAITING FOR GODOT and a good part of these sales came to us through amateur productions. A special group handles the amateur production rights to this play, and we cooperate with them in a mutually agreeable manner.”25 Some years later, Rosset had to clarify to Gallimard himself the nature of the paperback Evergreen Originals that were sold in this manner: “It is not really equivalent to a ‘livre de poche,’ since it is a full-sized book, selling for approximately $1.95. We have found that the major market for the Ionesco works is in the academic fields, and most of the books are purchased by professors and students.”26

The first Ionesco Evergreen Original was Four Plays (1958), whose design and format significantly contrast with those of Waiting for Godot. The very inclusion of four plays in one volume—The Bald Soprano, The Lesson, Jack, or The Submission, and The Chairs—both mitigates against the idea of a singular masterpiece and contributes to the sense of clutter between the covers. Instead of a photograph from a production—the conventional design for playscript covers—Grove used one of Kuhlman’s typographic designs, featuring simply a large, black number “4” against an orange background, with a thin strip of white along the left border in which appear the titles of the individual plays in orange. The white background of the border extends into the orange background of the number “4” in horizontal bars of uneven length and dimension, reinforcing the sense of busyness and blurred boundaries (Figure 13). The text itself includes no blank pages and minimal white space. The dialogue wraps around into the speech prefixes, further filling the space of each page. The four plays in this volume complement this sense of clutter, featuring proliferations of prattle and props. Starting with Ionesco’s first play, The Bald Soprano, famously inspired by an English-language primer, and ending with The Chairs, whose elaborate set becomes increasingly congested, the text of Four Plays feels chaotic and confusing.

Figure 13. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the first Ionesco Evergreen Original, Four Plays (1958).

Richard Coe, in his study of the playwright, argues that Ionesco “raised language from the status of a secondary medium to the dignity of an object-initself,”27 and this objectification is immediately evident in The Bald Soprano, which consists entirely of banal clichés without reference to plot, story, or character. This play in particular seemed to call for innovative book design, and in 1965 the French graphic artist Robert Massin, working with photographs of the revival performance directed by Henry Cohen, produced a radically experimental text of the play that Grove reissued in the United States. As the promotional flyer affirms, the book was meant to re-create graphically the experience of the play’s performance: “Like Ionesco’s play itself, it manages to break every rule of conformist book design with a tour de force of explosive image and symbol. All criteria of margin allowance, type combination, spacing and legibility are violated. Yet it brings the action of the play into electrifying life as though each spread were a frame from a flickering silent film arrested momentarily in startling black and white.”28 Grove tried to market this deluxe edition as a gift book in 1966, trumpeting in the press release: “NEW EDITION OF IONESCO’S PLAY THE BALD SOPRANO USES PHOTOS AND TYPE IN A UNIQUE WAY TO CONVEY ON PAPER THE QUALITY OF A LIVE PERFORMANCE,”29 but, as Fred Jordan wrote to Marshall McLuhan in 1967, “For some reason I am not fully able to understand, sales on the book have been disappointing.”30

An elaborately illustrated oversized hardcover, the Massin edition of The Bald Soprano is a remarkable work of art, but its commercial failure affirms the success of the more modest and affordable design of the Evergreen Original, which had no real equivalent in the Parisian book market. Neither a livre de poche nor an objet d’art, the Evergreen Originals format fused economic affordability and aesthetic quality without being seen as middlebrow. Although the design of these inexpensive paperbacks was meant to give a sense of performance conventions, this correlation could not, as with the Massin edition, compromise their affordability, which was crucial to the democratic ideology of their marketing. Thus, Grove promoted Four Plays in the same way as Beckett’s work, arguing that the printed text provided the opportunity for readers to determine the plays’ significance for themselves. The ad in the Times asked readers, “Are Eugene Ionesco’s plays ‘pretentious fakery’ or ‘amusing and provocative’? Make up your mind—read 4 Plays by Eugene Ionesco.”31 Although he didn’t sell as well as Beckett, Ionesco nevertheless became a reliable author for Grove: Four Plays sold more than ten thousand copies per year throughout the 1960s.

Grove also used Ionesco’s own pronouncements about the freedom of the artist to bolster its campaign. Ionesco wrote extensively about the theater, and Grove’s publication of his Notes and Counternotes in 1964 played an important role in framing his reception in the United States. In the preface, Ionesco apologizes for the repetitiveness of the collection, explaining, “I have been fighting chiefly to safeguard my freedom to think, my freedom as a writer.”32 And he extends this freedom to his audience, proclaiming in his ambivalent response to the success of Rhinoceros in the United States: “A playwright poses problems. People should think about them, when they are quiet and alone, and try to resolve them for themselves, without constraint.”33 Ionesco presents a complementarity between the collective and chaotic confusion of seeing the play and the solitary and quiet contemplation afterward, clearly an ideal context in which to read the Evergreen Original.

Within the literary field of the United States the theater of the absurd generated a mandate not only to read the plays before or after or instead of seeing them but also to read an expanding canon of commentary intended to frame the meanings of these difficult texts. No Grove Press playwright carried a heavier paratextual burden than Jean Genet, whose reception in both France and America was guided, if not determined, by Jean-Paul Sartre’s gargantuan study Saint Genet, ensuring that Genet’s work would initially be understood in terms of the reigning philosophy of existentialism, which formed a kind of interpretive frame around the entire theater of the absurd. Furthermore, Sartre’s opus was written before Genet turned to theater; thus, its focus on his poetry and prose, on his becoming a writer, ballasted his literary credentials and bolstered the common interpretation that he was a poet who had turned to the theater.

Rosset was introduced to Genet’s work by Bernard Frechtman, who, according to his partner at the time, Annette Michelson, “invented Genet for the English-speaking world.”34 Frechtman wanted Grove to begin with The Thief’s Journal, which he called “one of the profoundest books of this century,”35 but Rosset, after seeking legal advice, wrote back that “the Genet book would absolutely be banned and criminal proceedings invoked, and they would probably be successfully invoked to the extent of a jail sentence.”36 In the early 1950s, publishing Genet’s prose unexpurgated would have been foolhardy even for Rosset, so he wisely decided to start with the plays, effectively inverting Genet’s reception in France. After some wrangling, Frechtman accepted this decision.

The Maids, with an introduction by Sartre and a copyright in Frechtman’s name, was issued as an Evergreen paperback in 1954. Sartre’s introduction, originally an appendix to Saint Genet, reads the play in terms of the thematic concerns of the novels that form the literary focus of the second half of his monumental study, establishing them as crucial for understanding the play and laying the groundwork for their eventual publication by Grove in the 1960s after the legal triumph with Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Sartre understands the play in classically existentialist terms, arguing that “the maids are relative to everything and everyone; their being is defined by absolute relativity. They are others. Domestics are pure emanations of their masters and, like criminals, belong to the order of the Other, to the order of Evil.”37 Sartre’s philosophical terminology became crucial not only to framing Genet’s reception in the United States but also to understanding the broader historical and political developments with which his work was increasingly associated.

As were those of Beckett and Ionesco, Genet’s plays were popular on college campuses, and Grove replicated the practice of encouraging theater departments to sell the paperback in conjunction with their performances. In the late 1950s, both Harvard and Yale put on productions of Deathwatch, and Wellesley did a production of The Maids. Grove prepared a boilerplate letter that opened in this way: “We were wondering if you would be interested in selling copies of our $1.45 edition of THE MAIDS and DEATHWATCH, in the theatre on the evenings of your performance. This has been very successfully done by other groups which have produced the play.”38 Another version elaborates: “Often people are interested in reading a play right after seeing it.”39

The characters and settings in these first plays—maids, prisoners, and, in The Balcony, a brothel—were at best ancillary to the sensibilities of most Americans who saw or read them. Not until the publication of The Blacks in 1960, followed by its triumphant and controversial three-year run at the St. Mark’s Playhouse starting in 1961, did Genet become thoroughly assimilated into the American cultural and political scene. In his introduction to The Maids, Sartre had noted that mistresses create maids in the same fashion that “Southerners create Negroes”;40 the publication and performance of The Blacks provided the opportunity for Americans, both black and white, to contemplate this claim and, in a larger sense, to gauge the relevance of Sartre’s philosophical premises for their own most immediate social and political concerns.

The Blacks appeared on the American scene well before civil rights had given way to Black Power, before the term “Negro” had ceded its prominence to “black” in the volatile vocabulary of race relations in the United States. Rosset had originally intended to entitle it “The Negroes,” as he emphasized to Frechtman in late 1959: “We’ve had a great deal of discussion about the title and feel that it absolutely must stay as THE NEGROES. We do not feel that THE BLACKS has as much bite nor is as acceptable.”41 Frechtman was adamant in his refusal: “The title must be THE BLACKS. THE NEGROES is absolutely out of the question . . . Negroes is a purely neutral and even scientific term. It could be used in the title of an anthropological or sociological work.”42 Eventually Richard Seaver communicated Grove’s concession: “We give in. Reluctantly and contre coeur . . . THE BLACKS here has a rather ugly connotation rather than the bite you mention.”43 In the end, the publication and performance of The Blacks in the United States arguably contributed to the terminological shift from the purportedly neutral term “Negro” to the more aesthetically and politically loaded “black.”

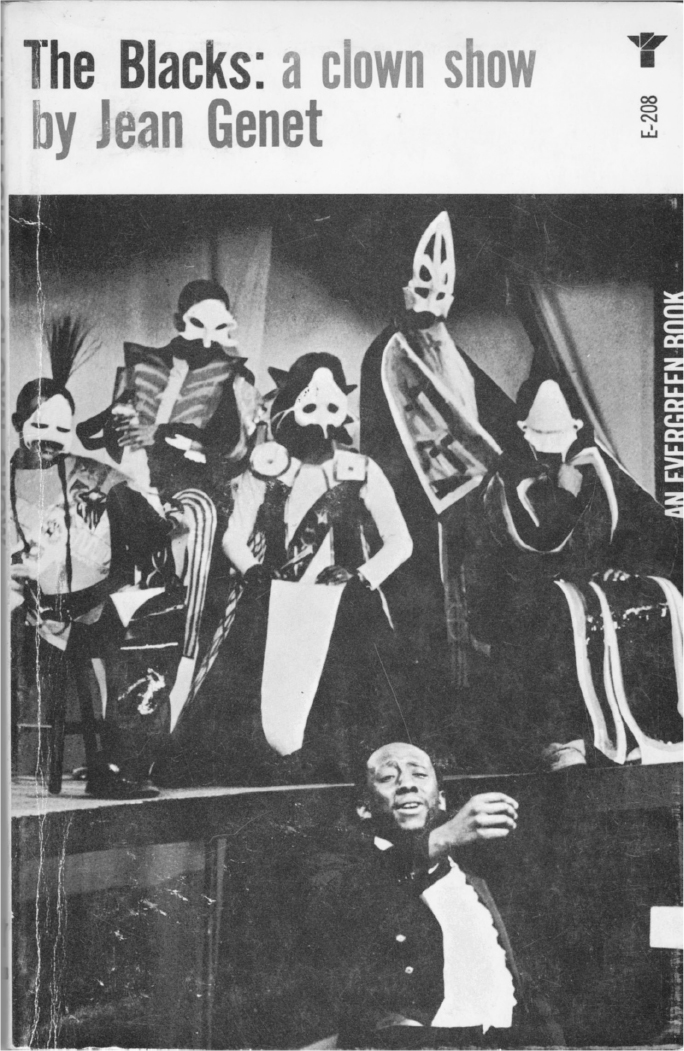

More than any other play Grove published, The Blacks was inextricably yoked to a specific American performance, photos from which were generously distributed throughout the paperback reissue of the play, which sold more than eighty thousand copies over the course of the 1960s. The cover photo features Roscoe Lee Browne in the role of Master of Ceremonies Archibald Absalom Wellington, his hand raised as if conducting a symphony. Above him looms the “Court,” five black actors in garish outfits and grotesque white masks. In contrast to the stark black and white of the cover photo, the title across the top features three colors: “The Blacks” in black; “a clown show” in orange; and “by Jean Genet” in purple, as if implying that the aesthetic form of the play is in tension with its philosophical premises (Figure 14). There are no blank pages in the text, nor is there any paratextual material besides Genet’s provocative instruction that the play “is intended for a white audience.” In addition to Browne, the original New York cast featured James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett Jr., Cicely Tyson, and Maya Angelou Make; the interspersing of their photos throughout the text creates a fascinating tension between the generic anonymity of the masks that illustrate the play’s purportedly existential philosophy of race relations and the idiosyncratic specificity of the faces that soon became highly recognizable in the American media, partly as a result of the publicity around this play.

Print and performance are deeply interdependent in The Blacks, both within the plot—which persistently foregrounds its scriptedness—and in the critical controversies around it, in which the disputants seem scripted into roles determined by their race. The play itself, of course, comments on this interconnection between race, writing, and role playing, since its central conceit is a performance by blacks of white fantasies about blackness. Thus, early in the play Archibald admonishes the character of Village (played by James Earl Jones): “You’re to obey me. And the text we’ve prepared.”44 One of the early photos features Village’s ambiguous declaration of hate to Virtue (played by Cicely Tyson), during which Archibald makes the conducting motions depicted on the cover, “as if he were directing Village’s recital,” according to Genet’s footnote.45 The subtle transit between the footnote and the cover photo, between Genet the playwright and Browne the actor as Master of Ceremonies, generates a tension between actors and script that illuminates the terms in which the play was discussed at the time.

Figure 14. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for The Blacks (1960).

This tension was the central subject of Norman Mailer’s review of The Blacks, spread over two issues of the Village Voice in May 1961 and then reprinted in The Presidential Papers in 1964. Revisiting the racial essentialism of “The White Negro,” Mailer asserts that the actors are members of the “Black Bourgeoisie” who “cannot know because they have not seen themselves from outside (as we have seen them), that there is a genius in their race—it is possible that Africa is closer to the root of whatever life is left than any other land.”46 Further elaborating that “the Negro tends to be superior to the White as an entertainer, and inferior as an actor,” Mailer concludes that the cast was too inhibited and self-conscious to fully inhabit Genet’s incendiary dialogue. In the next issue of the paper Lorraine Hansberry offered both Mailer and Genet as examples of “the New Paternalism” and reminded Voice readers that The Blacks must be understood as “a conversation between white men about themselves.”47 Furthermore, she vociferously defended both the actors and the acting, proclaiming that she knew most of them to be “part-time hack drivers, janitors, chorus girls, domestics” and that she found “the acting, almost without exception, brilliant.”48

In its self-conscious reprise of the dispute between Mailer and Baldwin over “The White Negro,” the disagreement between Mailer and Hansberry feels scripted, as if both were playing roles of which they were becoming weary, preventing either of them from fully engaging the challenges of Genet’s play. It is thus informative to contrast their conventional exchange with Jerry Tallmer’s review of The Blacks, which appeared alongside Mailer’s. Tallmer, cofounder of the Voice and contributing editor to the Evergreen Review, chose to review the play in the form of a dramatic dialogue between Village and Virtue, allowing him to comment more immanently on the complex rhetorical structures of Genet’s text. Significantly, Tallmer opens by appropriating Genet’s prefatory comment, which was not included in the showbill for the play and therefore would be familiar only to those who had read it: “One evening an actor asked me to write a play for an all-black cast. But what exactly is a black? First of all, what’s his color?”49 Then Tallmer begins:

VILLAGE: If we are not what they think us, neither shall we avoid being invented, being evacuated, by their thoughts. What then are we?

VIRTUE: Blacks, Clowns, Phantasms, of Jean Genet.

VILLAGE: What exactly is Jean Genet? First of all, what’s his color?

VIRTUE: White.

VILLAGE: What color is that?

VIRTUE: Pink, orange, yellow, black. Black as the ace. Black as sin. Black as diamonds. Black as the black semen of hatred. Black as genius. Black as the black chambers of masterpiece.50

Tallmer’s review begins by inverting Genet’s comment, routing the opening question back through the playwright and seemingly anticipating the color dynamic of the Evergreen paperback that incorporated photos from the New York production. Tallmer uses the same formal mimicry to comment on the identity of the actors:

VILLAGE: Do you speak as a white?

VIRTUE: As a Negro and a performer. Is not each of us—are not you—a Negro and a performer?

VILLAGE: I am Deodatus Village, rapist of the unraped, murderer of the unslain. I am a performer. Deodatus James Earl Jones Village.

VIRTUE: A Negro?

VILLAGE: A young American Negro. My name is Jones.51

Tallmer’s dialogic response to The Blacks comments more cogently than Mailer’s or Hansberry’s on the complex racial and rhetorical dynamics of the cast’s position in the New York production. And Tallmer concludes by claiming that such dialogue is only the beginning of a new rhetoric of revolution: “In the new swamps, the new colonialism. Slaves, criminals, Negroes, put on your masks; clowns, take your places. What does not yet exist must now be invented. It begins; it is only the beginning.”52 While Mailer and Hansberry’s exchange looks back to the context of the 1950s and the beginnings of the civil rights movement, Tallmer’s appropriation of Genet looks forward to the alliance in the later 1960s between the New African Nations and the Black Power movement, an alliance in which both Genet and Grove Press played a role.

The early and sustained prominence of Beckett, Ionesco, and Genet in Grove’s list of contemporary dramatists attests both to the persistent power of Paris as a cultural capital in the immediate postwar era and to the quality of the literary connections Rosset and company had there. After Paris, the most significant European capital of dramatic innovation was undoubtedly London, and Grove also established an impressive list of playwrights from the United Kingdom, including Brendan Behan, John Arden, Alan Ayckbourn, Joe Orton, and Tom Stoppard. The most successful and influential of this list was certainly Harold Pinter, whose collected works Grove began issuing under their mass-market Black Cat imprint in the 1970s. As the introduction to the first volume of the Complete Works of Harold Pinter, Grove chose “Writing for the Theatre,” the transcript of a speech Pinter gave at the National Student Drama Festival in Bristol in 1962, which was reprinted in the Evergreen Review in 1964. Commenting on the contrasting critical responses to his first two major plays, Pinter dryly and dismissively opens: “In The Birthday Party I employed a certain amount of dashes in the text, between phrases. In The Caretaker I cut out the dashes and used dots instead . . . So it’s possible to deduce from this that dots are more popular than dashes and that’s why The Caretaker had a longer run than The Birthday Party.”53 Pinter’s comment is intended as a dig at his critics, who “can tell a dot from a dash a mile off, even if they can hear neither,”54 but his wry dismissal of the relation between punctuation and performance can’t help having a rhetorical boomerang effect in retrospect, given the importance of pauses in his plays. As Worthen affirms, “In the first decade of Pinter’s real celebrity, the material idiosyncrasies of Pinter’s printed text drove the understanding of Pinter’s dramatic writing,” and no idiosyncrasy was more prominent than Pinter’s famous pauses that, as Worthen further elaborates, tend to assimilate the plays into a temporality associated with “certain kinds of reading.”55

For Worthen, Pinter’s pauses function within a larger literary temporality that is explicitly poetic since, as Martin Esslin affirms, Pinter “is a poet and his theatre is essentially a poetic theatre.”56 For both Worthen and Esslin, Pinter’s poetics are those of the modernist lyric, precise and pregnant with hidden meanings that can become legible through close critical attention to their arrangement on the page, and usually with the help of a critic who can explain, as Esslin notes in the preface to his book-length study of the dramatist, “much that is puzzling, obscure, and evokes a desire for elucidation.”57 This correlation between Pinter’s plays and modernist poetics receives further affirmation from his self-fashioning as an author. As he continues in his speech, “The theatre is a large, energetic, public activity. Writing is, for me, a completely private activity, a poem or a play, no difference . . . What I write has no obligation to anything other than to itself.”58 Given such dedication to the autonomy of the writer, it is not surprising that Varun Begley has recently suggested that Pinter supplant Beckett as “the last modernist.”59

The antinomy between private writing and public performance is folded into the setting and substance of most of Pinter’s early plays, almost all of which take place in the sorts of constrained domestic spaces where reading and writing frequently occur. Indeed, as Begley affirms in his interpretation of the significance of the newspaper in Pinter’s work, everyday reading, as opposed to “poetic” reading, is frequently thematized as a component of the action in his plays. Both The Birthday Party and The Room, published together as an Evergreen Original in 1961, open with a principal male character reading, only partially attending to the dialogue of the principal female character. Significantly, then, the opening pauses in these plays indicate a man reading while his wife speaks. The Birthday Party begins with the following lines between Meg and her husband, Petey, who is sitting at the kitchen table reading a newspaper:

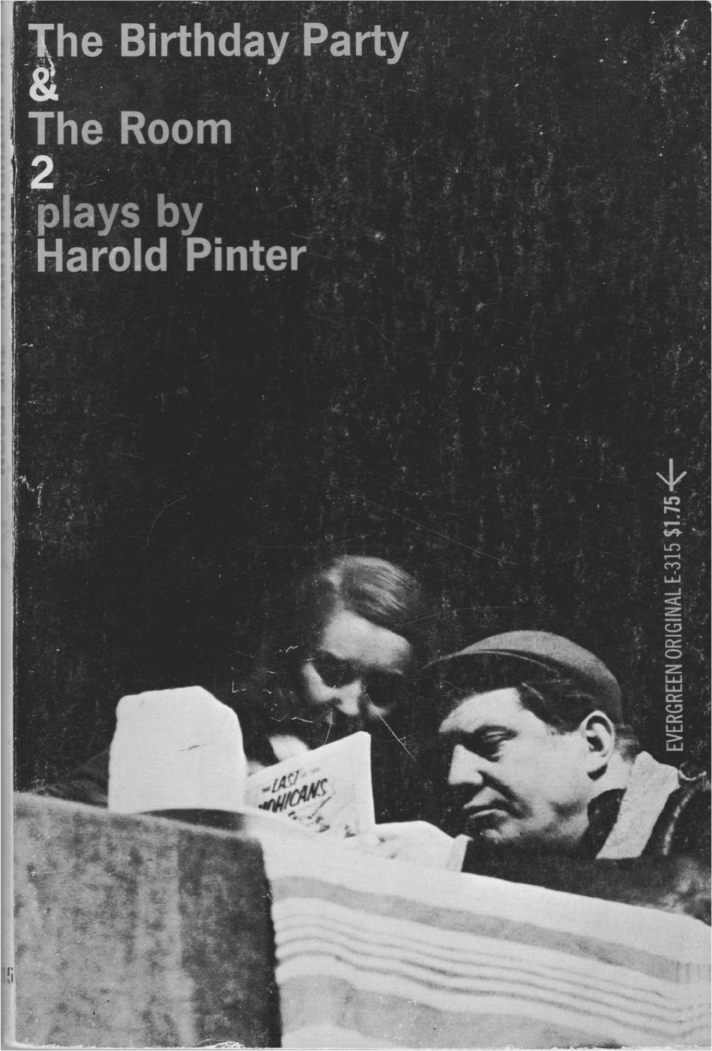

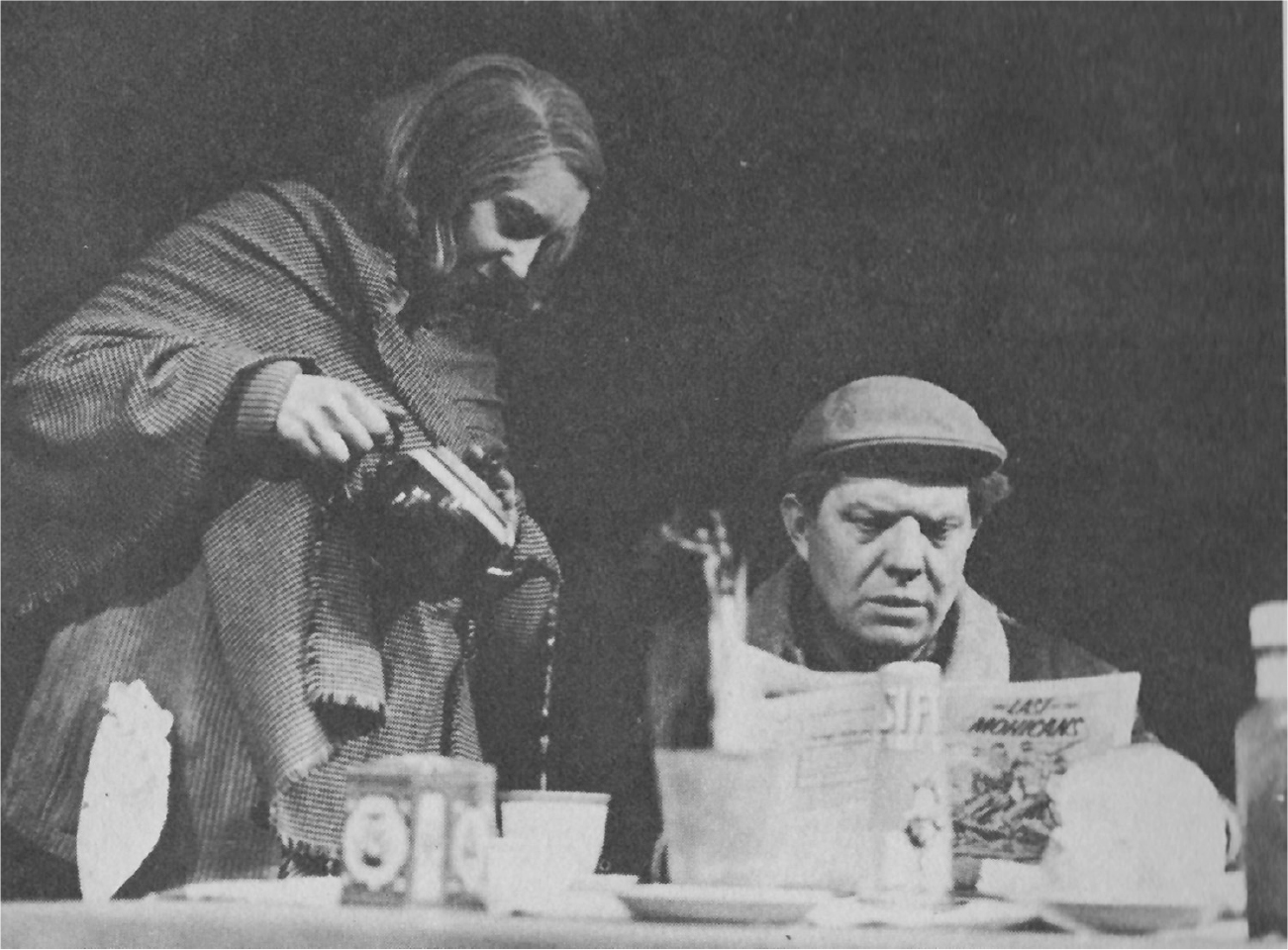

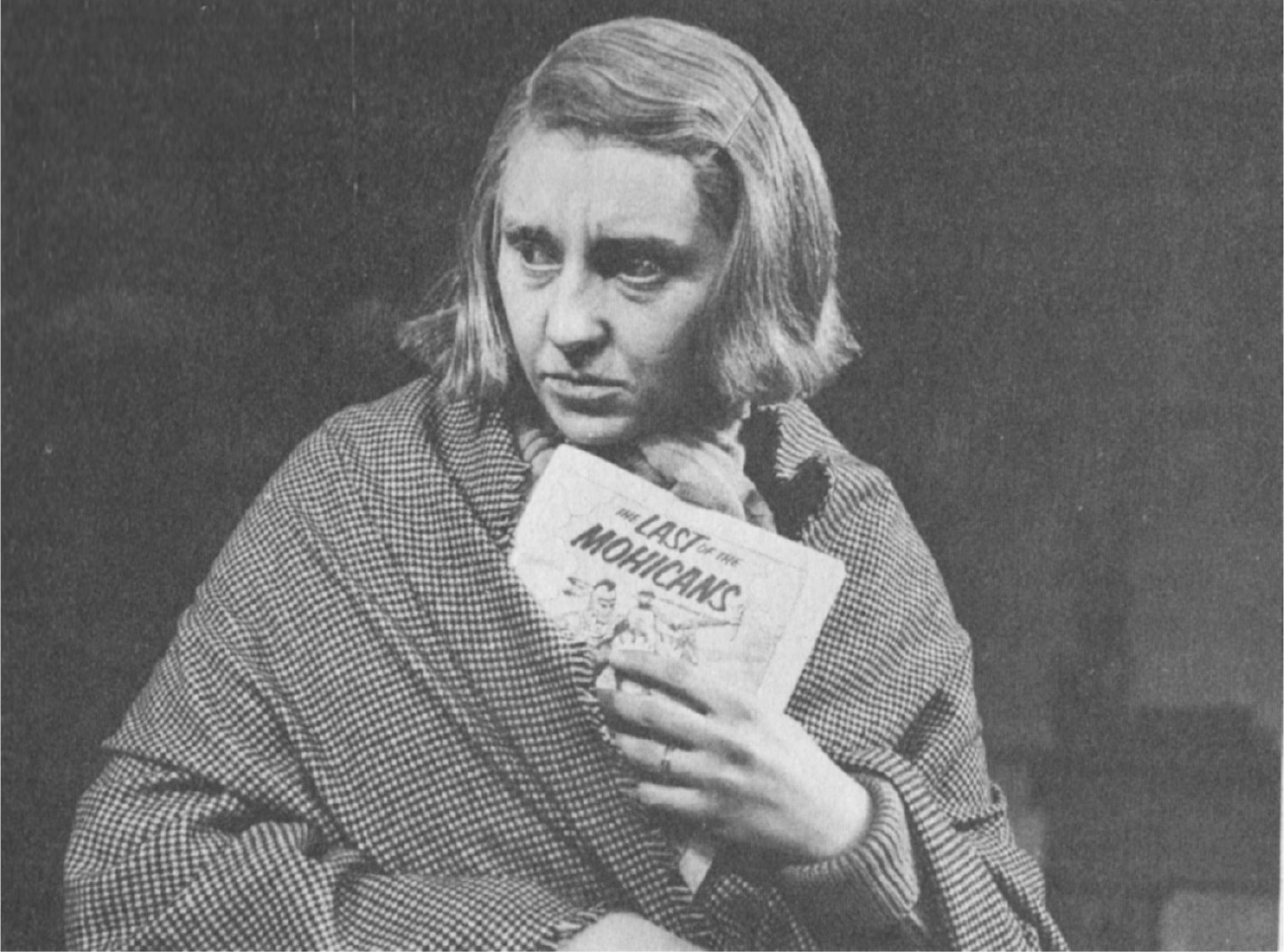

The Room opens with an almost identical scene between the couple Rose and Bert, in which Rose addresses a long monologue to Bert as he sits silently reading a magazine. In this scene, instead of simply indicating pauses, Pinter inserts extensive stage directions detailing Rose’s actions as she prepares Bert’s meal. This scene was chosen as the cover photo for the Evergreen Original. It is a low-angle, black-and-white close-up of Bert sitting at the table with Rose, her face partly in shadow, leaning over him; between the two of them is propped the magazine with the title The Last of the Mohicans, presumably serialized, just showing over the edge of the table that juts into the foreground of the shot. Above their heads the background is entirely black (Figure 15).

As the design of this edition indicates, Grove chose to introduce Pinter’s peculiar sensibilities—what quickly became known as the “Pinteresque”—through a dialogue between typographic and photographic representation. Since most of Pinter’s early plays take place in domestic interiors, they are particularly conducive to the photographic frame, whose rectangular shape conveniently mirrors the geometry of the room. In The Birthday Party & The Room a sequence of photos follows the text of each play, replicating in condensed visual stills the action the reader has just followed in print. Frequently these photographs represent silences in the text; the first photo from The Room is a frontal shot of Bert sitting at the table, the magazine propped in front of him, as Rose pours him a cup of tea (Figure 16). The third photo depicts a subtle alteration of the action described in the printed text. It shows Rose, alone, in the process of concealing the magazine in her shawl (Figure 17). Based on its order in the sequence, one can deduce that this photo represents her solitary actions between Bert’s departure and the arrival of Mr. and Mrs. Sands, which Pinter describes at some length:

He fixes his muffler, goes to the door and exits. She stands, watching the door, then turns slowly to the table, picks up the magazine, and puts it down. She stands and listens, goes to the fire and warms her hands. She stands and looks about the room. She looks at the window and listens, goes quickly to the window, stops and straightens the curtain. She comes to the centre of the room, and looks towards the door. She goes to the bed, puts on a shawl, goes to the sink, takes a bin from under the sink, goes to the door and opens it.61

If The Room, in its pure reduction to a single interior space, epitomizes Pinter’s settings, the surreptitious transit of a serialized American novel across the photographic reproductions of this space reveals how Grove worked to replicate its complexities in textual form. Pinter’s printed dialogue tends to hover over or penetrate into silences that indicate modes of everyday reading that significantly contrast with the type of attention solicited by the dialogue. The selection of photographs for this text foregrounds this dynamic, ensuring that Pinter’s pauses will be pregnant with the practice of reading in mind, a practice that, increasingly, was inculcated in the college classroom.

Figure 15. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Evergreen Original edition of

The Birthday Party & The Room (1961).

Figure 16. Vivian Merchant and Michael Brennan in Harold Pinter’s The Room (1960). (Royal Court Theatre, London; photograph by John Cowan)

Figure 17. Vivian Merchant in Harold Pinter’s The Room (1960). (Royal Court Theatre, London; photograph by John Cowan)

. . .

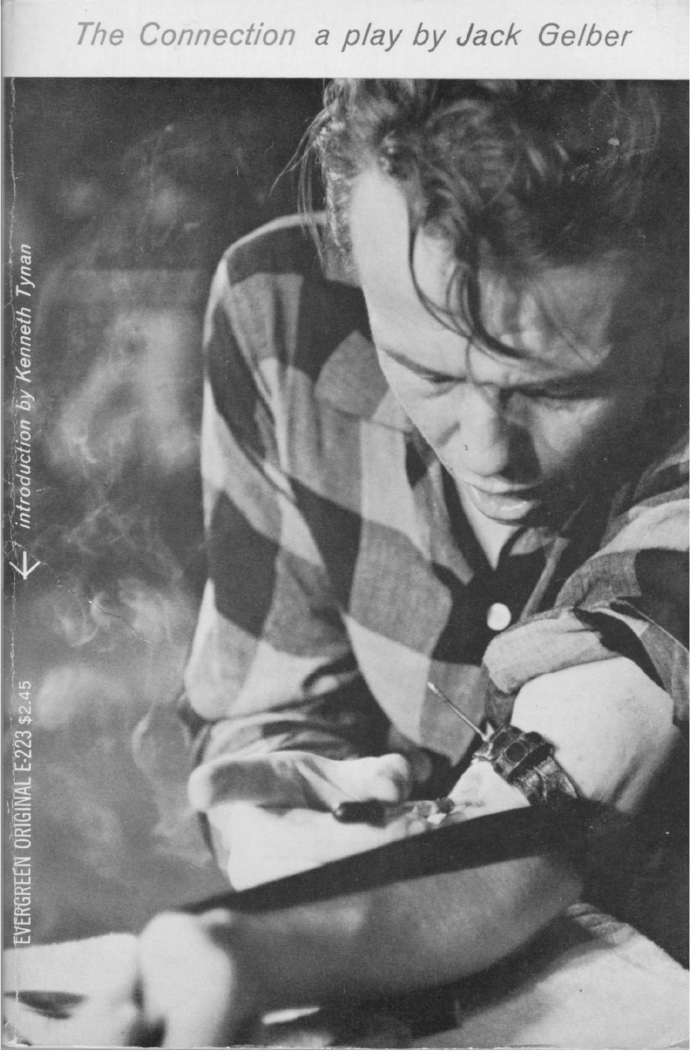

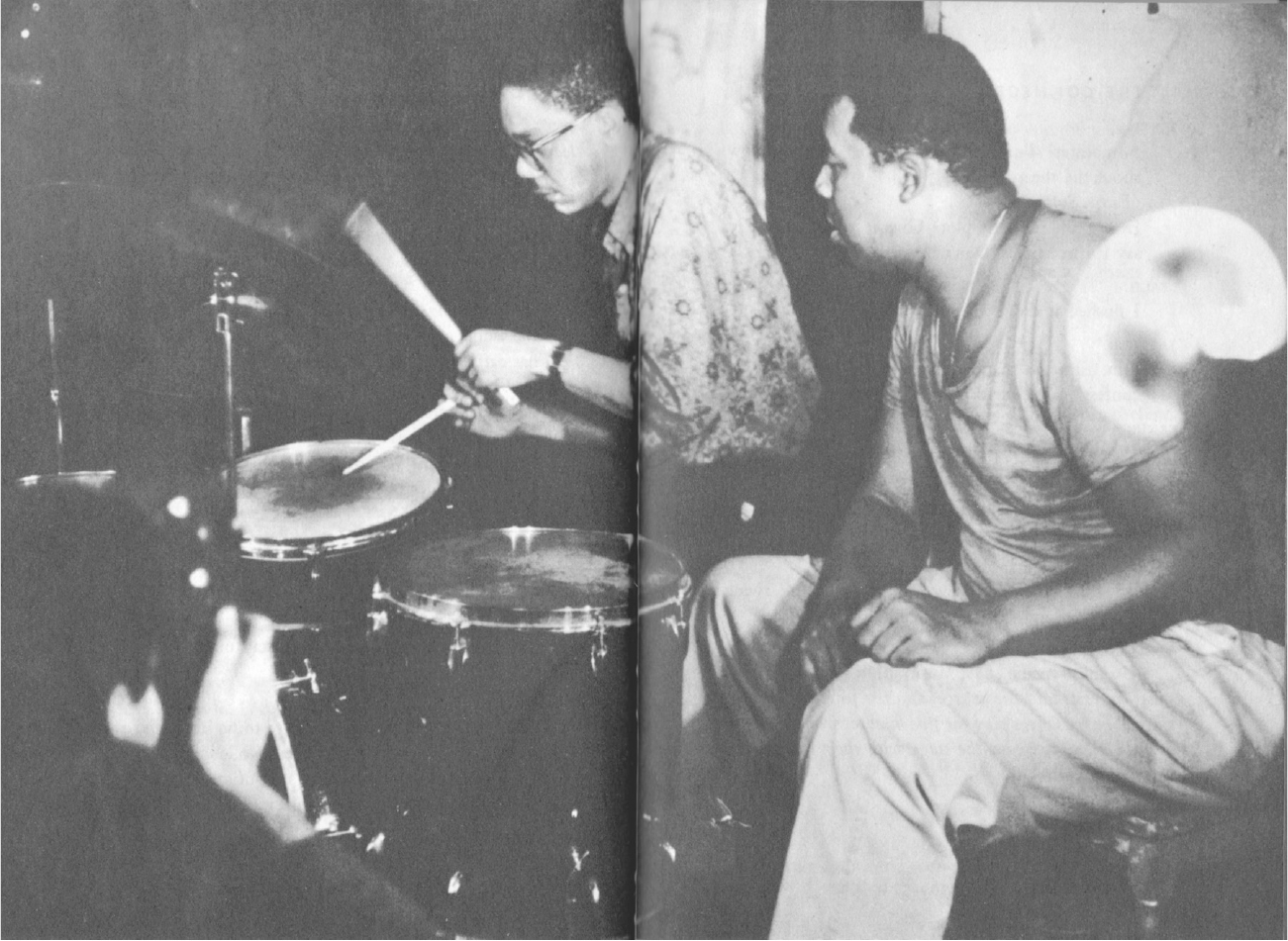

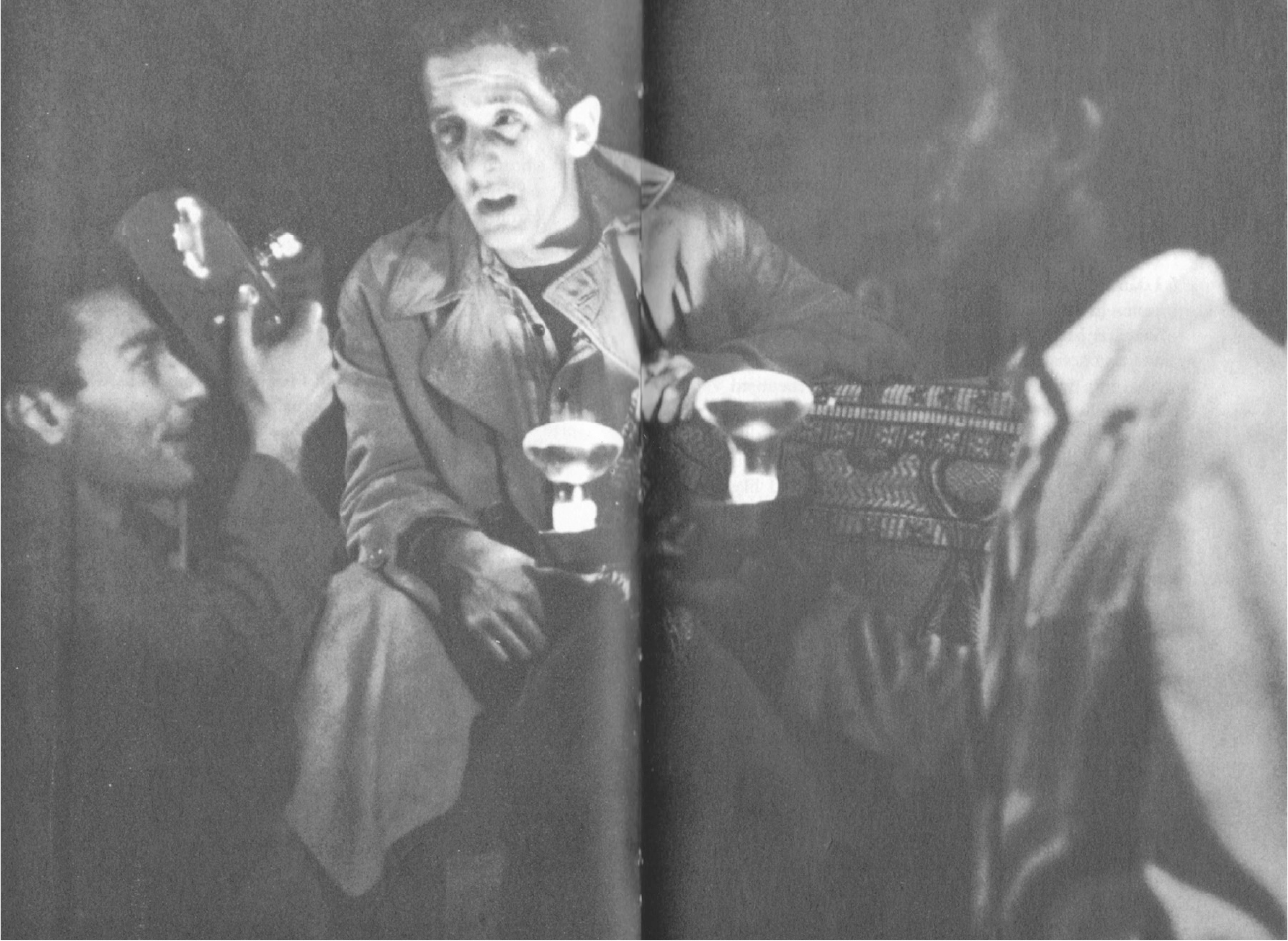

Grove’s resolutely international list of dramatists was weighted toward the European, but it did not neglect contemporary American drama, particularly with the now-legendary Living Theatre only a few blocks away. Grove published one of its first real successes, Jack Gelber’s The Connection (1960), a plotless play-within-a-play that centers on a group of addicts in an apartment as they wait for the dealer to arrive. As Kenneth Tynan notes in his introduction, “Its theme is akin to that of Waiting for Godot” but with a higher level of explicit self-reflexivity about its status as a performance.62 The cast includes a producer, director, and author, as well as two photographers who move in and out of the audience. It also includes periodic performances by jazz musicians.

Grove made ample use of photographs in its print edition. Kuhlman’s controversial cover features a close-up of the character Leach leaning over a table shooting up, with smoke curling in the background (Figure 18). Photos are generously distributed throughout the text, some across both recto and verso pages, many including the photographers and musicians (Figures 19 and 20). The photos function analogously to the musical interludes in the performance (recordings of which were available through Blue Note records), encouraging the reader to experience pauses in the lackadaisical action. Most of the photos are dark and grainy; many of them prominently feature the stage lighting. Thus, they create a paradoxical combination of verisimilitude and self-reflexivity. On the one hand, the front cover is startlingly realistic, and the murkiness of the photos in the text reinforces the underground atmosphere of the action. On the other hand, the presence of photographers reminds the reader that this is a performance about a performance, the kind of metalevel theatrical experience that became a signature of the Living Theatre.

Figure 18. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for The Connection (1960).

Figure 19. Musicians in Jack Gelber’s The Connection (1959). (Living Theatre, New York; photograph courtesy of John Wulp)

Figure 20. Photographers in Jack Gelber’s The Connection (1959). (Living Theatre, New York; photograph courtesy of John Wulp)

In the ensuing years, the Living Theatre performed The Connection across Europe, generating a cultural countercurrent to the stream of European avantgarde drama appearing in the United States in the postwar era. The Living Theatre itself was deeply influenced by the European avant-garde. Both Julian Beck and Judith Malina had been inspired by the theories of Antonin Artaud, and in the 1950s the struggling repertory company had staged work by absurdist forebears Alfred Jarry, August Strindberg, and Luigi Pirandello. They also staged a number of productions by another of Grove’s more important dramatic acquisitions, Bertolt Brecht, whose mentor, Erwin Piscator, had also been a strong influence on Malina.

Unlike Beckett, Ionesco, Genet, Pinter, Gelber, and the many other young and relatively unknown playwrights Grove published and whose careers it was therefore able to nurture from the beginning, Brecht was dead by the time Grove established itself as a publisher of contemporary drama, and he already had a towering reputation reaching back into the modernist era. Furthermore, the condition of his literary estate was a crazy quilt of textual variants and conflicting copyright claims. The key figure in Grove’s acquisition and marketing of Brecht was Eric Bentley, Brander Matthews Professor of Dramatic Literature at Columbia University and drama critic for the New Republic. As a translator, editor, and critic, Bentley, who had also been a personal friend of Brecht, introduced his work to the English-speaking world after the playwright’s death. Bentley first approached Rosset and Donald Allen in the mid-1950s, suggesting that they devote an issue of the Evergreen Review to Brecht. Allen thought that such an issue would have too narrow an appeal and instead suggested “a one volume selected Brecht, his own theory and some of the plays . . . the kind of one vol. that students would have to have, etc. Bentley would be a good editor.”63 Grove published the hefty Seven Plays by Bertolt Brecht in 1961, and Bentley, in close coordination with Fred Jordan, continued on as the general editor of the never-completed Grove Press edition of the Works of Bertolt Brecht.

The year 1961 was a turning point for Brecht’s career in English. In addition to the Grove publication of Seven Plays, the Tulane Drama Review devoted an entire issue to his work, including the first English translation of his essay “On the Experimental Theater.” Also in 1961, Anchor Books released a massmarket version of Martin Esslin’s Brecht: The Man and His Work. Grove issued its own Evergreen Pilot study of Brecht by Ronald Gray. Together, these publishing events laid the groundwork for the popular availability of English translations of Brecht’s work that Bentley envisioned for the Grove Press edition.

Grove emphasized the scale and scope of Seven Plays in its ads, calling it “one giant volume of the lyrical, cynical, grim, comic plays of Bertolt Brecht.”64 Crucial to the design of this near six hundred–page tome was a selection of Brecht’s early work, before his conversion to Marxism. The inclusion of these plays allowed Bentley to frame Brecht as an absurdist forebear, in essence reverse-engineering his appeal. As the flyleaf affirms, the volume features “the great early plays in which critics have found the beginnings of that Theater of the Absurd which we associate with the names of Beckett and Ionesco.” This design also enabled Bentley to argue in the introduction that, despite Brecht’s political transformations and the collaborative nature of most of his work, his oeuvre has the unity and coherence necessary to place him in the ranks of his modernist contemporaries.

Brecht’s plays, according to Bentley, are essentially poetic since, as he argues in his introduction, Brecht “remained the Poet as Playwright.”65 Esslin agreed that “Brecht was a poet, first and foremost.”66 For both Bentley and Esslin, Brecht’s poetic sensibility unites a corpus that would otherwise lack coherence, since Brecht resisted authoritative written versions of his plays and collaborated so extensively on their composition and production as to solicit sustained charges of plagiarism and exploitation. Nevertheless, Bentley insists, “In the Brecht theatre, though others made contributions, he himself laid the foundation in every department: he was the stage designer, the composer, and the director. The production as a whole, not just the words, was the poem. It was in essence, and often in detail, his poem.”67 Drama is collaborative; poetry is solitary. In order to establish Brecht as a modernist auteur, Bentley projects the latter onto the former. As we have already seen, this logic pervaded the positioning of Grove’s list of major playwrights; it allowed the dramatist to claim the autonomy of the poet and provided a reason to read the plays.

Seven Plays—as well as the entire Grove Press edition of Brecht’s works—was itself a highly collaborative and complicated endeavor. In addition to Bentley’s translations of In the Swamp, A Man’s a Man, Mother Courage, The Good Woman of Setzuan, and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (with Maja Apelman), it includes Frank Jones’s translation of Saint Joan of the Stockyards and Charles Laughton’s version of Galileo. Each play has its own title page, detailing its copyright and permission status (only Galileo has a copyright in Brecht’s name). Bentley’s introduction, subtitled “Homage to B. B. by Eric Bentley,” based on his Christian Gauss seminar on Brecht from the previous spring, is characteristically scattered and feisty, in essence a series of polemical observations and interventions intended to jump-start “a real discussion of Brecht.”68 Bentley’s commentary on Brecht’s collaborative methods is as revealing about him as they are about his subject. Bentley notes: “It has not escaped attention that, following the title page of a Brecht play, there is a page headed: Mitarbeiter—Collaborators. It has only escaped attention that these names are in small type and do not appear on the title page of the book or, presumably, on the publisher’s royalty statements.”69 It is impossible not to notice that the title page of Seven Plays prominently features Bentley’s name but doesn’t mention the many translators and editors who assisted him in his task. These names appear in the acknowledgments, which conclude with the following lines: “Finally, I wish to thank Mr. Barney Rosset. There’s a lot of prattle in America about enterprise. Barney Rosset, so far as my personal acquaintance goes, is one of the few enterprising Americans.”70

This enterprise came to partial fruition over the course of the 1960s, as Grove issued a variety of Brecht’s plays as part of the Grove Press edition of the Works of Bertolt Brecht, under Bentley’s general editorship. Most of these plays were published as mass-market paperbacks under Grove’s Black Cat imprint, reflecting an aspiration toward a popular audience appropriate to Brecht’s political vision.71 The proliferation of cheap paperback editions of his plays—pocket parables, as it were—alongside their frequent production by college and university drama departments over the course of the 1960s, illustrates the degree to which Bentley’s domestication of Brecht for an English-speaking public was based in a dialectical interplay between reading and spectatorship.

In his introduction to Seven Plays, Bentley calls “epic theatre” a “misnomer” for Brecht’s work, partly because he thought the term diminished appreciation of Brecht’s “lyric” talents but also because Brecht had failed to find a public adequate to his aspirations.72 A few years later, Grove published a play by a much younger German playwright who, according to Brecht’s mentor Erwin Piscator, fulfilled both the formal and political objectives of a modern epic theater. Rolf Hochhuth’s The Deputy, a lengthy free-verse moral melodrama indicting Pope Pius XII for his silence on the Holocaust, generated a firestorm of controversy from its debut in West Berlin on February 23, 1963. Since it was too long to be feasibly performed in a single evening, its German publisher issued the print edition on the same day as its debut. From its initial appearance, The Deputy was a play that demanded to be read.

The German debut of The Deputy was directed by Piscator, whom Brecht had earlier credited with “the most radical attempt to endow the theatre with an instructive character.”73 In his introduction to the print edition, Piscator called The Deputy “an epic play, epic-scientific, epic-documentary; a play for epic, ‘political’ theater, for which I have fought more than thirty years; a ‘total’ play for a ‘total’ theater.”74 This impassioned introduction appears as the first chapter in Eric Bentley’s edited volume for Grove, The Storm over “The Deputy,” the foreword to which bombastically claims that the controversy over this play “is almost certainly the largest storm ever raised by a play in the whole history of the drama.”75 Bentley goes on to explicitly compare this response to the relatively restricted audience for Brecht’s plays: “Who more than [Brecht] wished to speak to the whole modern world on burning issues that concern everyone? Yet the most one can say for the audience of Mother Courage, even where the play has been received most enthusiastically, is that it interests a rather considerable minority group.”76

Grove did its best to exploit the controversy that accompanied this play across Europe when it hosted Hochhuth’s visit to the United States for its American premiere (in an abridged version) at the Brooks Atkinson Theater in February 1964. Grove arranged for a press conference in the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria, where Hochhuth appeared with Fred Jordan at his side, as well as for a television interview with Hannah Arendt. The play ran for 316 performances, and the hardcover, released simultaneously with the premiere, was prominently reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, the New York Review of Books, and Bookweek. At 352 pages, including Hochhuth’s 65-page appended “Sidelights on History” documenting the veracity of his portrayals, The Deputy is almost as long as Seven Plays, dictating that it would rarely be performed in full.77 Thus, while its very length contributed to its claims to “epic” scale, it also determined that this scale could be fully appreciated only by reading it. In its ads, Grove specified that “this is not an acting version, but Rolf Hochhuth’s complete historical drama, which would take about eight hours to perform entirely, and from which every stage version has been adopted. Only by reading THE DEPUTY in this form can you realize the full depth and power of one of the most significant works to come out of postwar Europe.”78 This substitution of “work” for “play” indicated the difficulty in classifying this text. As the flyleaf affirms, The Deputy is “ostensibly a play, but transcend[s] the framework of the stage.” This “transcendence” is immediately evident in the opening stage directions, which include such editorial interjections as “it would seem that anyone who holds a responsible post for any length of time under an autocrat . . . surrenders his own personality” or “it seems to be established, therefore, that photographs are totally useless for the interpretation of character.”79 The lengthy text that follows looks like a cross between a George Bernard Shaw play and an epic poem. Set with minimal white space, the text fills every page, with stage directions frequently extending over five or six pages.

Critics were divided on the aesthetic value of this text, which, with the exception of one character, a Jesuit priest who voluntarily commits himself to Auschwitz (where the last act takes place) after he is unable to convince the pope to publicly condemn the Final Solution, is highly documentary in character, hewing closely to historical persons and events. As such, The Deputy depicts in stark immediacy events that precipitated the theater of the absurd but that are rarely directly referenced in it. More specifically, in attacking the pope, The Deputy directly engages the challenge that the Holocaust posed for the moral and institutional power of Christianity. Thus, The Deputy penetrated directly into the mainstream, in contrast to the “considerable minority” that discussed Beckett or Brecht, explicitly challenging the beliefs and allegiances of millions of people in a popularly accessible form and format (the massmarket edition, distributed by Dell, sold more than two hundred thousand copies). It is little surprise that the bibliography appended to Bentley’s edited volume runs to almost twenty pages, with many entries from Catholic and Jewish dailies.

Though none of Brecht’s plays generated the scale and scope of immediate controversy that followed the performance and publication of The Deputy, the “considerable minority” that read them ultimately ensured their longevity, whereas Hochhuth’s incendiary drama, and the “storm” over it, has vanished into relative obscurity—surely because it never entered into the college curriculum. This symptomatic division between drama as a direct intervention in current events—indeed, as an “event” in and of itself—and drama as a literary genre studied in the classroom is elegantly illustrated in the contrasting legacies of two plays Grove published in Black Cat editions in the late 1960s.

In August 1965, student activist Barbara Garson, speaking at an antiwar rally in Berkeley, accidentally called the president’s wife “Lady MacBird Johnson.” Inspired by her felicitous slip of the tongue, Garson over the next few years penned a full-length Shakespearean parody of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, based on Macbeth but making ample use of other of Shakespeare’s plays. In 1966, a draft of Macbird! was printed by the Independent Socialist Club of Berkeley and began circulating among Movement intellectuals on both coasts, generating considerable buzz in countercultural circles. Given that the borrowed plot dictated that the title character successfully plan the assassination of his predecessor, John Ken O’Dunc, Garson had difficulty interesting mainstream publishers in Macbird!, so her husband founded the Grassy Knoll Press explicitly for the purpose of issuing the play. By January 1967, the play had gone through five printings of more than 105,000 copies.

The play debuted at the Village Gate Theater on January 19, 1967, featuring Stacy Keach in the title role. Showcard, the company that produced off-Broadway playbills, refused to print one for the performance. Grove, which had already obtained publishing rights from Grassy Knoll, stepped into the breach. Later that year, Rosset bought Showcard, and for the rest of the 1960s Grove became the principal producer of playbills for off-Broadway performances, further enhancing its connections in the downtown scene and its reputation as a publisher and promoter of radical theater. The play generated considerable controversy and critical accolades, including gushing endorsements from Dwight McDonald, Richard Brustein, Eric Bentley, and Jack Newfield.

Macbird! was meant to intervene in its moment, and it paralleled current events so closely that Garson had to continue revising as new developments arose. The opening scene in a hotel corridor of the Democratic National Convention refigures the three witches as “a student demonstrator, beatnik stereotype,” a “Negro with impeccable grooming and attire” (played by Cleavon Little), and “an old leftist, wearing worker’s cap and overalls.”80 The opening lines, spoken in turn by the three witches—“When shall we three meet again? / In riot! / Strike! / Or stopping train?”—indicate the political immediacy of the action that follows. While that action tracks the structure of Macbeth, many of the most memorable lines, as well as the conclusion, in which Robert Ken O’Dunc (played by William Devane) arranges for the three witches to perform a play revealing Macbird’s guilt, are cribbed from Hamlet.

Thus, Polonius’s advice is twice parodied in speeches by the old leftist, who in the second scene recommends, “Neither a burrower from within nor a leader be, / But stone by stone construct a conscious cadre. / And this above all—to thine own class be true / And it must follow, as the very next depression, / Thou canst not be false to revolution”;81 in the last act he revises his advice: “But this above all: to thine own cause be true. / Set sentiment aside and organize. / It is the cause. It is the cause . . .”82 Hamlet’s soliloquy is wonderfully satirized in a speech by Adlai Stevenson’s character, the Egg of Head, who wonders, “To see, or not to see? That is the question. / Whether ’tis wiser as a statesman to ignore / The gross deception of outrageous liars, / Or to speak out against a reign of evil / And by so doing, end there for all time / The chance and hope to work within for change.”83 Not surprisingly, he opts for the former.

The play’s resolution is also borrowed from Hamlet, with Robert Ken O’Dunc conceding that he is “no Prince Hamlet nor was meant to be,” encouraging the three witches to perform a play in Macbird’s convention hotel room that reveals his guilt. The witches agree to perform but refuse to follow his script, as the second witch avers, “Man, we write our own lines. Screw your script.”84 In the next scene, he performs a minstrel show with the chorus: “Ober de nation / Hear dat mournful sound / Chickens coming home and roosting / Massa’s in the cold cold ground.”85 The play ends with Washington in flames and the Ken O’Dunc monarchy restored. Grove’s Black Cat paperback sold more than 250,000 copies in 1967.

If Macbird! appropriates Shakespeare toward immediate political ends, Tom Stoppard’s award-winning Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, originally performed in 1966 at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and then issued as a Black Cat paperback by Grove in 1967, had more long-term literary and philosophical objectives, making it more appropriate to the college curriculum. Realizing this potential, Grove’s education department issued a free study guide to accompany the play. The guide opens with a number of promotional blurbs, the first of which, from Clive Barnes’s review for the New York Times, is also featured on the play’s back cover. The last line—“Mr. Stoppard is not only paraphrasing Hamlet, but also throwing in a paraphrase of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot for good measure”—succinctly sums up the guide’s strategy, which reveals the degree to which the formal and thematic experimentation associated with the theater of the absurd had, over the course of the 1960s, been assimilated by the sensibilities of the paperback generation. Following the blurbs, the guide presents a letter from a Macalester College English professor attesting to the success of a paper assignment on Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. After three pages of excerpts from papers this professor received, Grove announces an essay contest on the same topic, to be judged by its editorial board. Grove promoted the contest aggressively, announcing in a press release: “ROSENCRANTZ AND GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD ADOPTED FOR CLASSROOM USE FROM COAST TO COAST; GROVE SPONSORS ESSAY CONTEST FOR STUDENTS.”86 The promotion was a success, with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead exceeding 150,000 copies in sales to educational institutions in 1968.

First prize in the contest was awarded to a seventeen-page research paper entitled “Hamlet and the Player” by a student at Vassar College. Echoing Grove’s study guide, which notes that “the Player is the richest role in R & G Are Dead,”87 the paper opens with the claim that “the player is just as much the hero as the title characters.”88 The paper’s second paragraph effectively reveals how thoroughly the formal and philosophical challenges of experimental theater had been domesticated into standard literary critical tropes:

Tom Stoppard has done what many college undergraduates now aspire to do in their papers; he has responded to a work of art not just critically but artistically as well. This, I think, is the highest compliment one can pay another artist. Stoppard has fashioned a play (whose central figure is the Artist, the player) based on a play (whose concern, in a great many respects, is Art). He has not just affirmed Shakespeare by choosing Shakespeare’s characters to make a story, or by balancing the “existential” mentality with Renaissance melancholy or the heroic death of Hamlet with the silent offstage deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern; he has affirmed Shakespeare simply by making a self-conscious play, one that has no other meaning than itself. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is finally “about” only Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.89

What follows is a lengthy development of the revealing analogue between the undergraduate essay and the work of art that comfortably recuperates existential angst into glib irony.

The author dwells explicitly on the relation between text and performance in his analysis of the exchange between Guildenstern and the Player during the rehearsal scene when, in response to Guildenstern’s question, “Who decides?,” the Player responds, “Decides? It is written.” As the author notes, “The word ‘written’ can have two meanings; first it is the ‘written’ text of the play which the players must follow . . . Secondly, ‘written’ suggests a fate which has been predetermined.” And he further elaborates that “the two meanings of ‘written’ can, of course, be one if we understand that the function of the dramatist, the artist, is to show fate operating in life, that is, to center his dramas and his art around the fact of death.” This assimilation of death into art, which will predictably lead to a conclusion about the immortality of art, forms the familiar argument of this paper, but the author is refreshingly aware of the degree to which the urgency of existentialism’s philosophical challenge gets lost when it is rendered as a problem for literary analysis. Thus, in commenting on Guildenstern’s resistance to the Player’s assertion, he claims, “He is not unlike many of us who write essays on the existential hero and Camus’s words in The Myth of Sisyphus about ‘the unyielding evidence of a life without consolation’ and then go on to worry about getting an ‘A.’ We are still looking for the consolation.”90

In its confident self-consciousness, this essay illustrates how completely the initial controversy over a play like Waiting for Godot, the paperback version of which had sold more than a quarter of a million copies by 1968, had been accommodated to the American classroom. The student is effortlessly comfortable with both the formal and philosophical difficulties of the avant-garde, even to the point of indicating the ironies of this easiness. In its emphasis on the literariness of these difficulties—the author ranges across the modern canon from Twain to Eliot to Hemingway to Yeats—the essay also reveals how essential the print versions of these plays were to this process. The author can console himself with the “immortality” of art only by assimilating the drama to its scripted form; performances, after all, are ephemeral.

Grove had chosen a topic, a comparison of Shakespeare and Stoppard, which in and of itself was calculated to subordinate performance to print. As Worthen affirms, the “New Bibliography,” which determined the print format of Shakespeare’s plays during this era (and Shakespeare was far and away the most-assigned English-language playwright across the educational spectrum), “tended to see the impact of theatre . . . as a distraction from, and corruption of, the proper transmission of the author’s writing,” thus envisioning “an author writing for posterity in print, producing an ideal and complete dramatic script that he knew could not be fully realized on stage.”91 By asking students to compare Stoppard (and, implicitly, Beckett) to the author whose work had effectively established the standard format for the play in print, Grove was affirming its remarkable success in marketing avant-garde theater as an explicitly literary genre whose authors were comparable to the most revered playwright in the canon.