|

The End of Obscenity |

|

The End of Obscenity |

The reputation Grove established over the second half of the 1950s for publishing quality literature was crucial to its success in the battles over obscenity and freedom of expression that took up much of Rosset’s time, energy, and money in the first half of the 1960s. Starting with Grove v. Christenberry (1959), the Post Office case over Lady Chatterley’s Lover that inaugurated the rapid dismantling of the Comstock Act; reaching a frenzied peak with the multiple trials and tribulations of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer across the country; and concluding with the exoneration of William Burroughs’s wildly explicit Naked Lunch in Massachusetts in 1966, Grove Press was central to the process that its lawyer Charles Rembar called the “end of obscenity” in his 1968 account of the trials. Rembar concludes his story with the lines, “So far as writers are concerned, there is no longer a law of obscenity,” and indeed censorship of the printed word in the United States essentially ended in the 1960s.1

Rosset planned his decade-long battle against censorship with both deliberation and determination; in one unpublished autobiographical fragment, he calls it “a carefully planned campaign, much like a military campaign.”2 Throughout this campaign Rosset and his lawyers—in addition to Rembar he worked with Edward de Grazia, Elmer Gertz, Ephraim London, and many others—emphasized Grove’s reputation as a publisher with literary credentials. In his affidavit for Grove v. Christenberry, Rosset affirmed that Grove publishes “works of a serious literary and artistic nature.”3 And for the many cases involving Tropic of Cancer, Rosset and his lawyers fashioned a boilerplate affidavit specifying that most of Grove’s titles “are in what is called the ‘quality paperback’ field” and that many of them “are in use in colleges and universities throughout the country, having been specifically adopted in various courses by departments and by individual instructors and teachers.”4 In turn, Rosset and his lawyers solicited the expert testimony of these academics to attest to the literary value of the texts charged with obscenity.

As Frederick Schauer affirms in his study The Law of Obscenity, the use of expert testimony “took on new meaning” after the passage of Roth v. US in 1957, the first case in which the US Supreme Court directly addressed whether obscenity constitutes an exception to First Amendment protection for freedom of speech and the press. Before that landmark case, experts were generally (and not always successfully) deployed to attest to the literary merit of works deemed obscene; after its passage, lawyers and their expert witnesses were provided with what Schauer deems to be “a uniform standard definition of obscenity”: “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.”5 In the wake of the so-called constitutionalization of obscenity precipitated by Roth, experts found that, in addition to establishing the literary value of purportedly obscene texts, they were also being asked to help the court determine the nature of the “average person” and of the “community standards” that “average person” should apply.

The court ruled against Samuel Roth, the “booklegger” who had earlier attained notoriety for pirating Ulysses. But First Amendment lawyers realized that by defining obscenity as material “utterly without redeeming social importance,” the court had provided them with an important weapon in the campaign against censorship. Roth represents the initial articulation of what Rosset’s lawyer Edward de Grazia later called the “Brennan Doctrine,” a developing definition of obscenity formulated by Supreme Court Justice William Brennan that would make it easier for “defense lawyers to demonstrate that the works of literature or art created by their clients were entitled to First Amendment Protection.”6 As De Grazia’s far-ranging study, Girls Lean Back Everywhere: The Law of Obscenity and the Assault on Genius, affirms, “experts” such as literary critics, authors, journalists, publishers, and college professors were central to this legal demonstration. Indeed, according to de Grazia, “The only significant breakthrough to freedom that was made over the past century by authors and publishers . . . was made when the courts were required by law . . . to admit and give weight to the testimony of ‘expert’ authors and critics concerning a challenged work’s values.”7

The gold standard of literary value for all of these experts and the publishers who retained them was James Joyce’s Ulysses, whose exoneration a generation earlier by Judge John Woolsey had become a landmark both in the battle for freedom of expression and in the academic canonization of modernism. Before the Ulysses case, the literary value of modernist texts had been difficult to legitimate because they had not stood the test of time. They had not become “classics” by the only standard widely recognized by the public at large: outliving their authors. The obscenity trial in this context functioned as a ritual of consecration whereby modernist texts could be affirmed as “classics” by experts on literary value. It enabled an alliance between publishers, lawyers, and literary critics that was crucial to providing mainstream acceptance for modernism by replacing the test of time with the patina of professionalism.

The US government itself acknowledged this emergent category when, in Section 305 of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, it allowed a Customs exception for “so-called classics or books of recognized and established literary . . . merit . . . when imported for non-commercial purposes.”8 Bennett Cerf’s lawyer Morris Ernst and his co-counsel Alexander Lindey leveraged Smoot-Hawley in their petition to the Treasury Department arguing that Ulysses is a “modern classic”: “We have long ago repudiated the theory that a literary work must be hundreds or thousands of years old in order to be a classic. We have come to realize that there can be modern classics as well as ancient ones. If there is any book in any language today genuinely entitled to be called a ‘modern classic’ it is Ulysses.”9 Over the next few decades, it became the job of literary critics to affirm the category of the “modern classic,” which Grove used both in its legal defense and in its commercial promotion of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tropic of Cancer, and Naked Lunch.10

During this period, the legal and economic extensions of obscenity were closely linked, since the federal government did not provide copyright protection for works deemed obscene. The illegitimacy of obscenity as literature, in other words, was reinforced by its exemption from the category of intellectual property. Joyce and Lawrence had no legal recourse against piracy, since they could establish no American copyright for their texts. Cerf’s decision to publish Ulysses promised to doubly affirm it as both a modern classic exempt from Customs confiscation and as legitimate intellectual property from which the author could profit.11 In order to establish Ulysses’s classic status and discourage further censorship and copyright challenges, Cerf included in Random House’s version of the text Woolsey’s “monumental decision,” a foreword by Ernst, and a letter from Joyce detailing his piracy woes, establishing a paratextual convention that Rosset followed closely in packaging Lawrence, Miller, and Burroughs.

Cerf used The United States of America v. One Book Called “Ulysses” to leverage Joyce’s masterpiece into Random House’s “first really important trade publication.”12 Ulysses’s modernist credentials were affirmed by its entry into the middlebrow marketplace, a paradox sustained by the successful marketing of modernism and the canonization of the new criticism that mandated the moral “disinterest” of literary value. What Susan Stewart identifies as a “’properly’ transgressive space” was established by an alliance between the expertise of academic critics and the marketing savvy of modern publishers; the “obscenity” of modernism was contained by its aesthetic consecration.13 The Ulysses case provided legal sanction for this containment. The law had acknowledged the expertise of literary critics, which in turn transformed the subversive tendencies of modernism from a liability to an asset in the cultural field. More than any other postwar American publisher, Grove Press capitalized on this transformation.

The idea to publish an unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was originally suggested to Rosset by Mark Schorer, whom Rosset confirmed was “a major figure in the beginning.” He became instrumental in defending, legitimating, and publicizing the text. A native midwesterner with a PhD in English from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, Schorer joined the English Department at UC Berkeley in 1945, where he served as chair from 1960 to 1965. A recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships and a widely respected critic and novelist informally known as the “Lionel Trilling of the West Coast,” Schorer became Rosset’s academic point man for Lady Chatterley’s Lover, negotiating (ultimately unsuccessfully) with Lawrence’s widow for the rights, providing Rosset with a list of experts from whom to solicit testimony, and writing the introduction to the Grove Press edition, originally published in the inaugural issue of the Evergreen Review.14

In early 1954, Rosset wrote to Ephraim London, already well known for having exonerated Roberto Rossellini’s film The Miracle of charges of obscenity, for legal advice on how to proceed with a defense of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. London responded, “The Ulysses case suggests an approach,”15 and Rosset in turn wrote to Schorer that “Ephraim feels that the best mode of procedure might be to more or less do what the ulysses people did.”16 Schorer provided Rosset with a list of potential experts, including Edmund Wilson, Jacques Barzun, Henry Steele Commager, and Archibald MacLeish. Rosset fashioned a boilerplate letter to be sent to these men, emphasizing that “in order to fight most effectively against such repressive and outmoded censorship, we shall need written opinions from responsible and eminent citizens to the effect that the book has literary value.”17 Barzun and Harvey Breit both provided testimonials that eventually appeared in the flyleaf of the Grove hardcover edition, and MacLeish wrote a preface to supplement Schorer’s introduction. Lawrence’s American biographer, Harry Moore, also supplied copy for the flyleaf, contending that “the time is overdue for an American publisher to make a fight for lady chatterley’s lover such as the one made . . . in New York in 1933 and 1934 . . . for Joyce’s ulysses.”

Obscenity, however, was not the only problem. There was no US copyright registered to Lady Chatterley’s Lover, precisely because it had been deemed obscene. Rosset wrote to Frieda Lawrence’s British agent, Laurence Pollinger, and to Alfred Knopf concerning the copyright to the text. Although Ephraim London had reassured him that the unexpurgated version was in the public domain, and he had received encouragement from Frieda to publish it, Rosset also knew that Knopf had in 1932 published an expurgated version to which it owned the copyright. Writing to Pollinger in June 1954, Rosset claimed, “As you know, LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER is no longer in copyright; however, in the happy (if not too likely) event that we can overcome censorship and proceed with publication, we will, as a courtesy, pay a standard royalty to the Lawrence estate.”18 Ominously, Pollinger responded, “I am not, I am afraid, prepared to agree to your statement that this novel is no longer in copyright in America . . . Of one thing I am absolutely certain, and that is that LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER is copyright[ed] in all the countries that signed the Berne convention.”19 Later that summer, Rosset wrote to Knopf, summarizing the efforts he had made and asking for reassurance that, if he succeeded in exonerating the book, he would be free to profit from its publication. As he argued, “We think we should win, and we also think that if we undertake the work and win the case we should then be the publisher of the book and thus gain any profits which might occur.”20 Knopf deferred to Pollinger, whose position was strengthened after Frieda Lawrence died in 1956, leaving the British agent as the literary executor of the Lawrence estate. On the advice of Ephraim London, Rosset temporarily shelved the project.

Three years later, encouraged by the passage of Roth and by London’s successful defense of the French film version, Rosset decided to proceed with publication, but then he ran into problems with London. According to Rosset, “We were in Boston with a bunch of Lawrence specialists, we were having lunch at Harvard, I disagreed with London on something . . . he said, ‘When you’re with me, do what I say.’ And I said, ‘You’re fired.’”21 The young man he hired to replace him, Norman Mailer’s cousin Charles Rembar, had never argued a case in court. But Rembar was a quick study and recognized the importance of the Supreme Court’s decision in Roth, which defined obscenity as material lacking “redeeming social importance.” As Rembar meticulously documents in The End of Obscenity, this language was central not only in the Lady Chatterley case but also in the cases involving Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and in the 1966 Supreme Court case exonerating Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. By 1968, the Supreme Court, partly through Rembar’s influence, had altered the definition of obscenity to material “utterly lacking redeeming social value,” effectively excluding print from prosecution.

Rosset had originally intended to precipitate a Customs case as Cerf had done with Ulysses, but the legal confrontation was ultimately with the US Post Office, meaning that it directly challenged the Comstock Act, which was almost a century old. The hardcover was impounded by the postmaster of New York in May 1959, the same month it made the New York Times bestseller list. A hearing was scheduled that included the Readers’ Subscription as co-plaintiff. As Jay Topkis, the counsel for Readers’ Subscription, affirmed in his opening testimony, “Our business depends completely on the use of mails. We operate through the mails exclusively. When we can’t send mail, we are out of business.”22 Readers’ Subscription president Arthur Rosenthal elaborated in his testimony later that day the extent to which book clubs helped publishers like Grove reach an academic market: “We do direct mail largely to what I call the university community: graduate students, assistant professors, professors.”23 Not only did Readers’ Subscription market to academics but its selections were in turn determined by them, as Rosenthal further affirmed: “Readers’ Subscription was founded in 1952 with three very prominent literary critics, W. H. Auden, poet, Jacques Barzun of Columbia, Lionel Trilling of Columbia, as people who were charged with the responsibility of selecting the books for this organization.”24 The presence of Readers’ Subscription as co-plaintiff affirms the centrality of the burgeoning academic community as both audience and authority in the trials to come.

Rosset was the first witness called, and the Post Office lawyer promptly challenged his testimony’s relevance, objecting that he “failed to see where we can gain anything by the testimony of the publisher of this book.” Rembar, referencing Earl Warren’s concurring statement in Roth, rebutted that “the conduct of the publisher is one of the elements that the courts have held relevant in a proceeding of this kind.”25 Then Topkis, citing Woolsey’s contention that “the intent with which the book was written must first be determined,” expanded the scope and relevance of Rosset’s testimony by claiming, “Here, we don’t have the author, we have the publisher.”26 Rosset further legitimated and distributed his implied expertise in divining Lawrence’s intentions, testifying that he “engaged Professor Schorer as an expert on this book, to be certain of the fact that when we published, we would have the authentic edition.” He then recounted his efforts to solicit expert opinions, after which Rembar and Topkis offered reviews of the book as evidence of its literary value. Over the objection of the prosecutor, the judicial officer, “relying on the decisions in the Ulysses case,” accepted them into evidence.27

The competence and relevance of expert testimony were central issues in this initial hearing. Rembar and Rosset had retained Malcolm Cowley and Alfred Kazin, and the government persistently challenged the nature and scope of their expertise. Both men emphasized their academic credentials, with Cowley offering that he had “been visiting professor at many universities” and Kazin similarly claiming, “I have been a visiting professor in various universities both here and abroad, at Harvard, Smith, Amherst, Cambridge.”28 Both men described themselves as literary sociologists with expertise that encompassed both the interpretation and reception of literature. Cowley identified himself as “a literary critic and historian . . . I have made somewhat of a specialty of the folkways of readers and writers; that is, my last book . . . was more or less a book of literary sociology rather than criticism.”29 Kazin also identified his specialty as “the trends of literary taste, what the public has responded to, what it has bought.”30 Both men claimed that Lawrence’s intention was to encourage sexual fulfillment in marriage and that the public, particularly on college campuses, was becoming increasingly tolerant of sexual explicitness, such that Lawrence’s text was no longer as offensive to public taste as it was when originally written.

Arthur Summerfield, Eisenhower’s postmaster general, was unconvinced and issued a departmental decision on June 11, 1959, concluding that “any literary merit the book may have is far outweighed by the pornographic and smutty passages and words, so that the book, taken as a whole, is an obscene and filthy work.”31 Rosset’s response was two pronged. First, he appealed to the court of public opinion, compiling “A Digest of Press Opinions” on Summerfield’s decision to be distributed “in the Public Interest.” All of these opinions, from newspapers across the country, challenged Summerfield’s competence to determine literary merit, many directly contrasting his authority with that of the critics whose evaluations he overruled. Thus, one opinion for the San Francisco Examiner of June 18, 1959, asserts: “Dear Mr. Summerfield . . . You say ‘Lady Chatterley’ is obscene. Are you as well qualified to judge a work of literature as Mark Schorer, Archibald MacLeish, Malcolm Cowley, Alfred Kazin and the host of other renowned scholars and critics who say it is not?”32 In the same month, Lady Chatterley’s Lover reached number 5 on the New York Times bestseller list.

Next, Rosset and Rembar decided, along with Readers’ Subscription, to sue the postmaster general of New York, Robert Christenberry, in federal court for impounding the book. Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan’s decision for the US District Court, issued on July 21, 1959, and affirmed by the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, finally overturned the Post Office ban. In his decision, which was published in full in the Evergreen Review and incorporated into the paperback edition of the text, Bryan affirmed that “Grove Press is a reputable publisher with a good list which includes a number of distinguished writers and serious works. Before publishing this edition Grove consulted recognized literary critics and authorities on English literature as to the advisability of publication. All were of the view that the work was of major literary importance and should be made available to the American public.”33

Three days after Judge Bryan issued his decision, New American Library, which Knopf had licensed to publish an expurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, sent out a “Signet Gram” announcing publication of “the unexpurgated and complete edition of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover,’ under their exclusive license for paperbound reprints of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover,’ granted by contract authorized by the author’s estate more than 10 years ago, still in full force and effect and just reconfirmed by the Lawrence estate and its literary executors.”34 No sooner had Rosset won the legal battle over obscenity than he found himself in a subsequent struggle over intellectual property. He brought suit against New American Library, not for copyright infringement, since it had been established that the book was in the public domain, but for “seeking to mislead and deceive the public” with its avowals that its edition was “complete” and “authorized.”35 As Publishers Weekly affirmed, this was less a legal issue than a matter of “the ethics of the publishing industry.”36 Most industry insiders believed that Rosset’s assumption of the original risks of publishing the unexpurgated edition gave him the exclusive right to profit from it and also acknowledged that “Grove’s performance in publishing its $6 hardbound edition of the book and in advertising and promoting it was in keeping with the book’s high literary standing” and had indeed been responsible for its legal exoneration.37 Grove settled with New American Library in the fall of 1959, with both companies agreeing to acknowledge the legitimacy of each other’s versions.

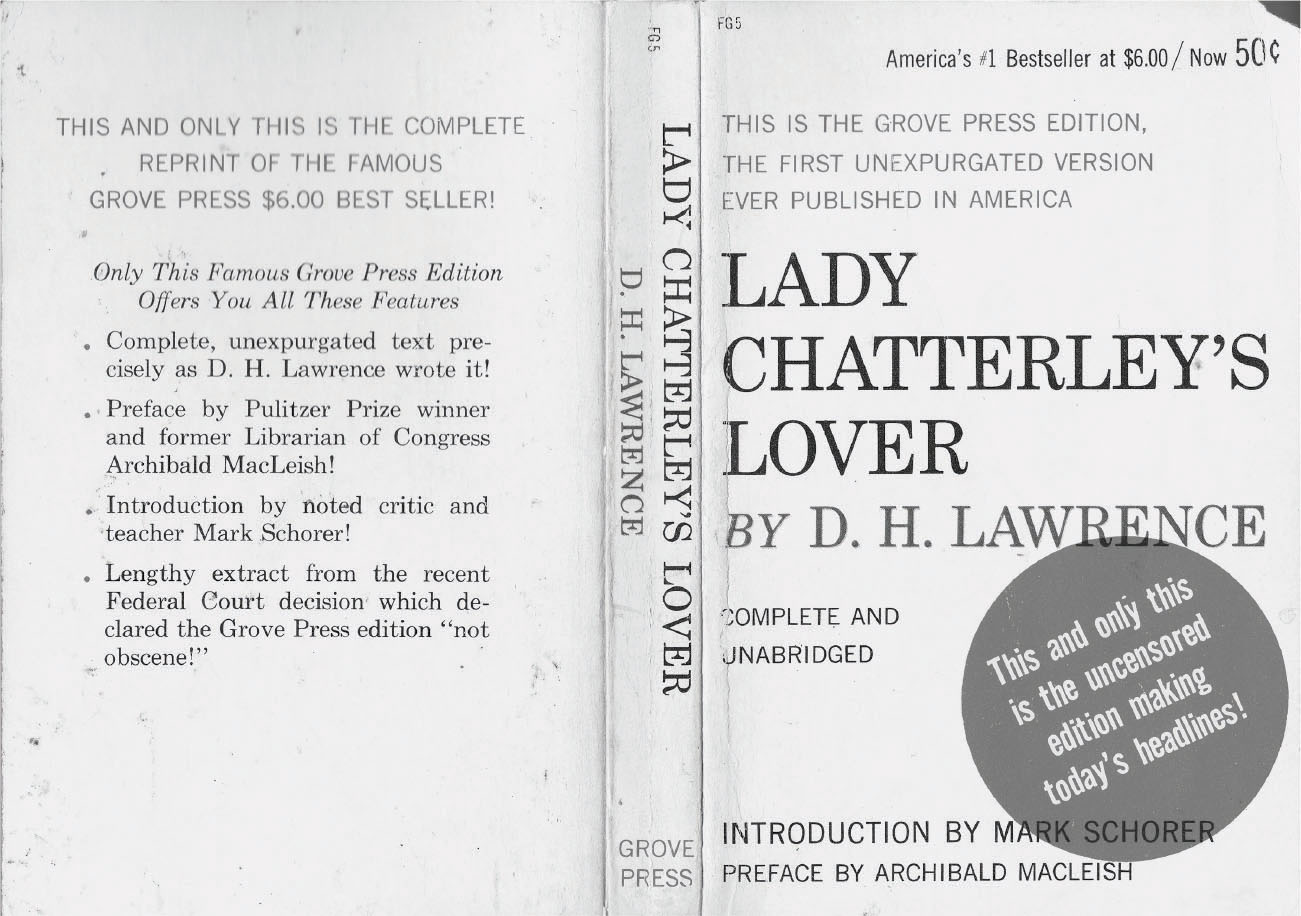

The design and composition of both paperback editions deploy a series of paratextual conventions intended not only to legitimate the literary authenticity of the text but also to distinguish it from their more salacious rivals in the field, eschewing illustration entirely for descriptive and promotional blurbs (in an unpublished interview, Rosset called the cover “very carefully uninteresting”).38 Like the hardcover, Grove’s paperback edition included Schorer’s introduction and MacLeish’s preface (framed as a letter to Rosset), now further supplemented by Bryan’s decision. On the front cover, in red caps, is trumpeted “THIS IS THE GROVE PRESS EDITION, THE FIRST UNEXPURGATED VERSION EVER PUBLISHED IN AMERICA”; on the back cover it reiterates, again in red caps, “THIS AND ONLY THIS IS THE COMPLETE REPRINT OF THE FAMOUS GROVE PRESS $6.00 BEST SELLER.” As if any question could remain, the front cover also includes, in yellow print against a red circular background, “This and only this is the uncensored edition making today’s headlines!” (Figure 21).

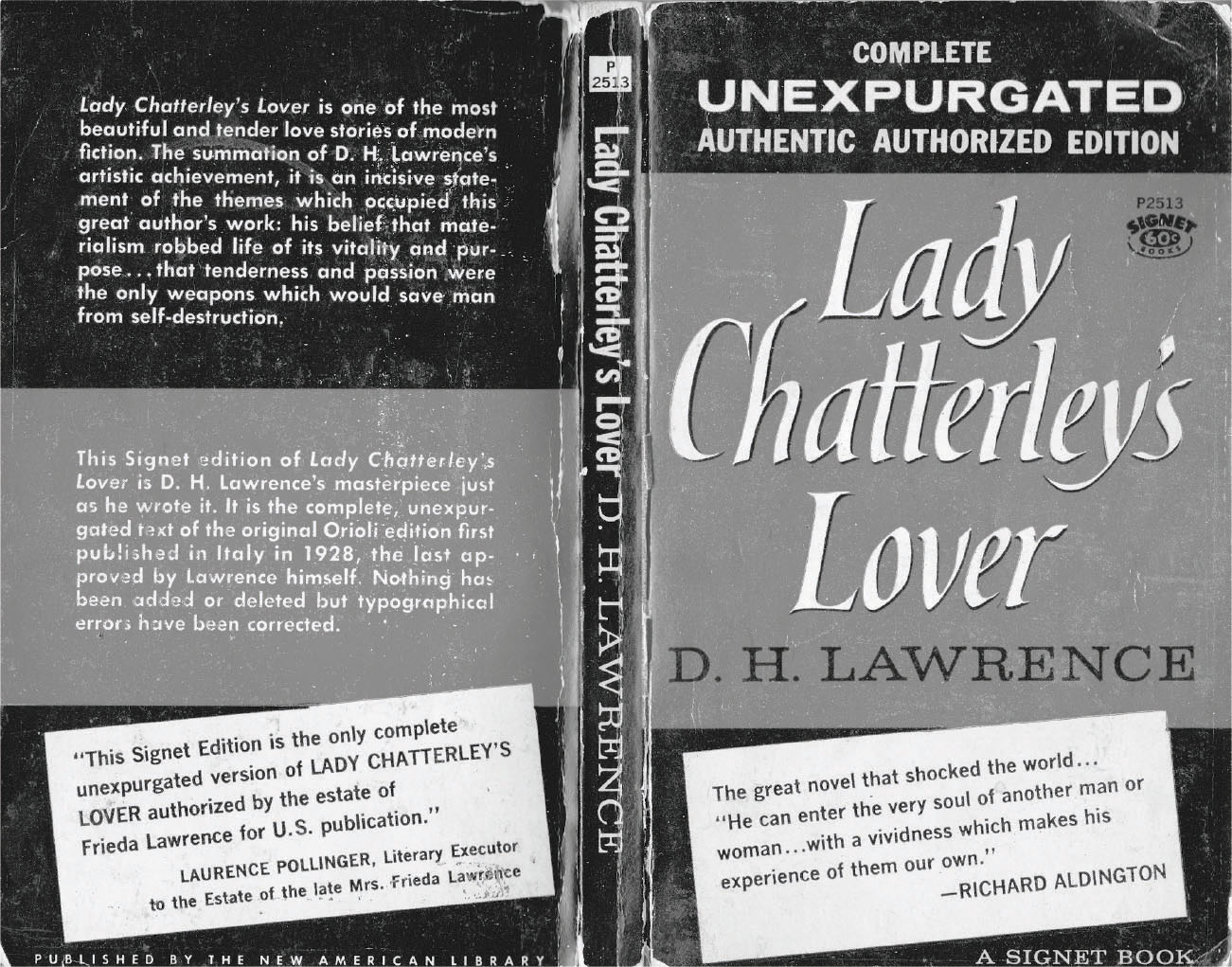

The Signet edition also announces tautologically that it is the “complete unexpurgated authentic authorized edition” and includes a statement on the back cover from Pollinger testifying, “This Signet Edition is the only complete unexpurgated version of LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER authorized by the estate of Frieda Lawrence for U.S. publication” (Figure 22). The Signet edition also included an afterword by Harry Moore, whose endorsement had originally appeared on Grove’s hardcover edition. Despite the competition from this and other paperback versions, the mass-market edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, distributed by Dell, became Grove’s first bestseller, with sales of almost 2 million copies by the end of 1960, and the legal battle provided a firm foundation for the reputation Grove continued to build over the course of the decade for challenging legal restrictions against freedom of expression.

Figure 21. Front and back cover of Grove Press edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1959).

Figure 22. Front and back cover of Signet paperback edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1959).

Rosset had not really liked Lady Chatterley’s Lover, but he thought that its exoneration would increase his chances of legally publishing Henry Miller, whose work he had admired since his undergraduate years. New Directions had published Miller’s less explicit writing, but Jay Laughlin was unwilling to publish the Tropics, which remained banned in the United States and Britain. Rosset was determined to bring them out, but Miller initially turned down his generous advance. As Rosset recounted to me, “I had tried to get Miller and totally failed. I’d gone to California, to Big Sur . . . and he said no . . . he said he couldn’t stand the idea. If I published it, it would be read by college students.” But Rosset persisted, and with the help of Girodias, whose father had originally published both Tropics, and Miller’s German publisher, Heinrich Ledig-Rowohlt, he finally managed to get Miller to agree to publication in the United States in 1961, with a substantial advance of fifty thousand dollars. Unlike the case of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which had been fairly easy and inexpensive to defend with the one Post Office case, Tropic of Cancer was suppressed and litigated in numerous venues across the country, while simultaneously enjoying many months on bestseller lists in those same venues. Henry Miller became both a cause célèbre and a succès de scandale, and the strategies of both his accusers and defenders illustrate how the elite aesthetics of modernism collapsed into a popular politics of sexuality in the 1960s.

Miller’s work had never been easy to categorize or evaluate. His biography, particularly his expatriation in the 1930s, tended to align him, albeit somewhat belatedly, with the modernist Lost Generation, but his unseemly and unwavering focus on this biography tended to violate the evaluative protocols critics used to canonize the work of that generation. Edmund Wilson, reviewing the then unavailable Tropic of Cancer for the New Republic in 1938, called it “an epitaph for the whole generation of American artists and writers that migrated to Paris after the war” and “the lowest book of any literary merit that I ever remember to have read.”39 In both his bohemian lifestyle and his literary experimentation Miller seemed to fit, if somewhat awkwardly, into the Lost Generation category. As one biographer describes, his aspiration was to be “a working-class Proust, a Brooklyn Proust.”40

However, as Partisan Review editor Philip Rahv affirmed, “With few exceptions the highbrow critics, bred almost to a man in Eliot’s school of strict impersonal aesthetics, are bent on snubbing him.”41 According to Rahv, Miller is incapable of this strict impersonality: “So riled is his ego by external reality, so confused and helpless, that he can no longer afford the continual sacrifice of personality that the act of creation requires, he can no longer bear to express himself implicitly by means of the work of art as a whole but must simultaneously permeate and absorb each of its separate parts and details.”42 In other words, Miller can’t afford, both literally and figuratively, to practice Eliot’s “impersonal” act of creation, even though his own aesthetic is clearly a dialectical response to that act, with whose Proustian protocols Miller was deeply familiar. Miller’s gargantuan personality, his maddening mix of garrulous charm and aggravating arrogance, emerges in ambivalent resistance to the figure of the modernist genius he can’t quite be.

Miller was not only too personal to be considered high modernist; he was also too popular, despite the difficulty in obtaining his work. As Kenneth Rexroth, writing on the eve of Miller’s American apotheosis, proclaimed, “Henry Miller is really a popular writer, a writer of and for real people, who, in other countries, is read, not just by highbrows, or just by the wider public which reads novels, but by common people, by the people who, in the United States, read comic books.”43 Much of Miller’s initial popularity was enabled not by the scattering of critical accolades but by the widespread smuggling of his banned books into the United States by GIs returning from World War II. In sum, Miller posed a problem for midcentury arbiters of literary taste.

Nevertheless, Rosset armed himself with an enormous battery of critical endorsements, since he knew from his experience with Lady Chatterley’s Lover that they could prove that a text had redeeming social value. He solicited written comments from an impressive roster of critics, writers, and publishers, including Jacques Barzun, Marianne Moore, Lawrence Durrell, Archibald MacLeish, W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Arthur Miller, Thornton Wilder, Vladimir Nabokov, Alfred Kazin, and Malcolm Cowley. Rosset was wise to prepare, as he was almost immediately engulfed in a firestorm of controversy involving more than thirty court cases and more than fifty instances of extrajudicial suppression across the country. Since he had agreed to indemnify booksellers against any fines or court costs and to handle all legal cases arising from the sale of Miller’s book, Rosset found himself battling for the financial survival of Grove Press.

Grove’s challenge is neatly summed up in the epigraph to Miller’s Black Spring, the lesser-known second volume in the trilogy that begins with Tropic of Cancer and ends with Tropic of Capricorn: “What is not in the open street is false, derived, that is to say, literature.”44 This dig at the very modernism with which Miller simultaneously endeavored to associate himself received an inverse ironic commentary in the trials of Tropic of Cancer, as experts in literature attempted to prove they had the street credentials to evaluate the book. The first trial, somewhat inevitably, was in Boston, for which Rosset rehired Ephraim London, who assembled an illustrious cast of experienced expert witnesses, including Mark Schorer, Harry Moore, and Harry Levin. However, the judge was not impressed by the credentials of these scholars, interrupting Schorer’s testimony with the quip that “all that was necessary in this case was to offer the book in evidence and then leave it to me, who knows everything about how the ordinary man feels and what his reaction would be.”45

Assistant Attorney General Leo Sontag agreed and attempted to establish that Schorer and the other witnesses for the defense were not in touch with the American public and therefore could not be expected to represent the book’s effects on an ordinary reader. Sontag proclaimed, “It’s said that a rarified atmosphere exists on the campus at the University of California at Berkeley.” The judge then required clarification: “Do you feel he is in an ‘Ivory Tower’ and therefore has no contact with ordinary human beings?” Sontag affirmed, “That is correct, your honor. The Professor is on a shelf by himself with others.” Schorer then quipped, “I’d like to tell you sometime the non-‘Ivory Tower’ aspects of my life.” London attempted to come to the rescue by reminding the court that “the judge’s life is, if anything, more of an ‘Ivory Tower’ existence than that of a college professor.” And the judge crankily responded, “We are on the street just the same as and as much as any ordinary being.”46

Who’s in the Ivory Tower and who’s on the street, and from which position is it most legitimate to judge a book like Tropic of Cancer? The courtroom would have to wait for Harry Levin’s testimony for an ironic resolution, although this was not fully recognized in the trial itself. London introduced him with the claim that “Professor Levin’s qualifications are so many that I would like to save a great deal of time by merely reading a few of them in the record and having the professor acknowledge that these are his accomplishments.”47 The judge was unimpressed until London concluded that Levin was the Irving Babbitt Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University. The judge and Levin then discovered that they both studied under Babbitt as undergraduates at Harvard. Although Judge Goldberg in the end disregarded the expert testimony and found the book obscene, this incidental exchange affirms the degree to which Rosset’s eventual triumph depended on the professional-class solidarity of the judges, academics, and publishers who participated in these trials, a solidarity that, somewhat ironically, could not fully include the author over whom they were struggling.

The Boston trial was handled in rem, meaning that the case was against the book itself. In the Chicago trial, handled by Elmer Gertz, the demographic alignments of the adversaries were far clearer. Tropic of Cancer was being illegally suppressed and confiscated across suburban Illinois, and the case pitted Grove against an array of small-town police departments, including Arlington Heights, Skokie, Glencoe, Lincolnwood, Morton Grove, Niles, Des Plaines, Mount Prospect, Winnetka, and Evanston. Rosset grew up in Chicago, where his father had been president of the Metropolitan Trust Company. Gertz surely must have felt reassured when Judge Samuel Epstein opened the proceedings with the claim, “I doubt if any lawyer, who is old enough, hasn’t had some sort of business relationship with Barney Rosset.”48 During the course of this widely publicized trial, Gertz also established an ongoing epistolary relationship with Miller himself, who was finally becoming wealthy as Tropic of Cancer rocketed up the bestseller lists. As Gertz advised Miller on various tax-evasion schemes, Miller sent him rare and signed editions of his books. A number of socioeconomic allegiances and alliances, then, contributed to Grove’s success in this landmark case, which Rosset saw as a “peak moment” in his career.49

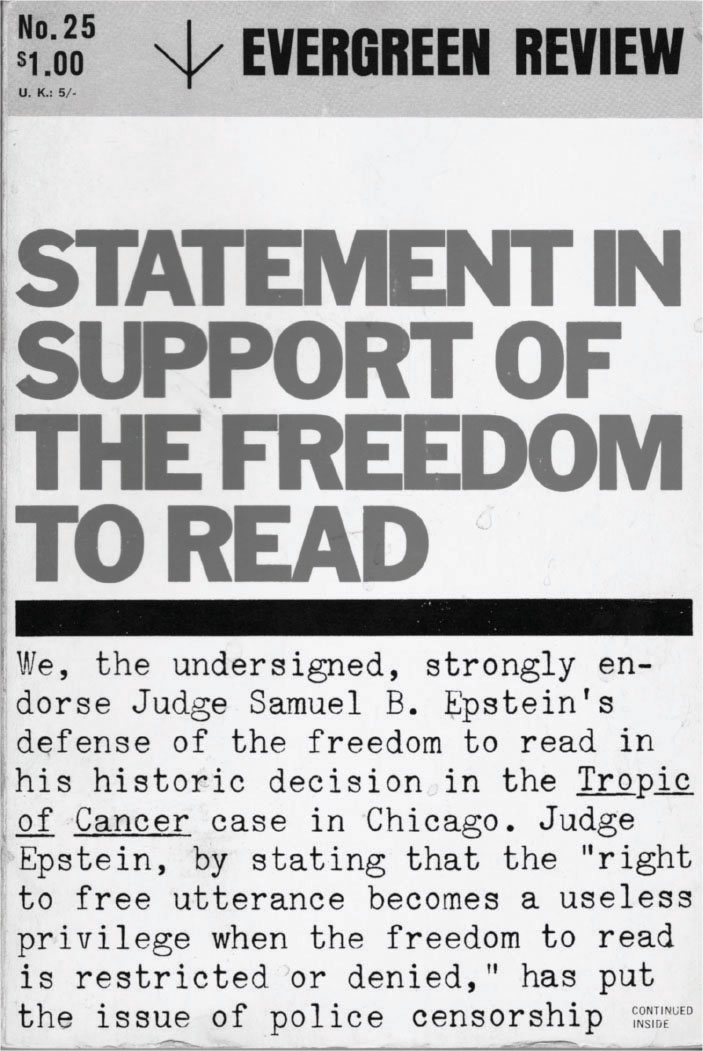

Judge Epstein’s ruling, which affirmed that “as a corollary to the freedom of speech and the press, there is also a freedom to read,” became the basis of a nationwide campaign.50 Rosset printed and circulated thousands of copies of the decision and published a “Statement in Support of the Freedom to Read” on the front cover of the July–August 1962 issue of the Evergreen Review, which also included Chicago Sun-Times book reviewer Hoke Norris’s account of the Chicago trial. The statement, which runs over from the front cover onto the flyleaf (Figure 23), is followed by a long alphabetical list of signatories, including James Baldwin, Ian Ballantine, Saul Bellow, Louise Bogan, Richard Ellmann, Arnold Gingrich, Hugh Hefner, Jack Kerouac, Carson McCullers, Marianne Moore, Lionel Trilling, and Robert Penn Warren. The statement shifts the terms of defense from elite endorsement to democratic access, affirming that “the issue is not whether Tropic of Cancer is a masterpiece of American literature” but rather “the right of a free people to decide for itself what it may or may not read.”51

Figure 23. Irving Cowman’s cover for Evergreen Review issued after Grove successfully defended its right to publish Tropic of Cancer (1962).

Grove was unable to appeal either Attorney General v. Tropic of Cancer or Franklyn Haiman v. Robert Morris et al. to the Supreme Court; thus, while Miller’s book remained a bestseller across the country in 1963, it was also unavailable in many locations, and Grove’s coffers continued to be drained by litigation. Yet another of Grove’s lawyers, Edward de Grazia, decided to appeal the Florida case of Grove Press v. Gerstein, which had been decided against Tropic, using the argument that the court had not yet determined “whether the Constitutional guarantees of free expression are not violated by the application of local, rather than national, ‘contemporary community standards’ to the question of whether a literary work may be suppressed as ‘obscene.’” Further on in his petition, De Grazia clarified that the issue of national standards concerns both “free artistic expression and freedom to read,” revealing his desire to incorporate Epstein’s formulation into the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the First Amendment.52

On June 22, 1964, the Supreme Court overturned the Gerstein decision and, in the attached case of Jacobellis v. Ohio, affirmed that “the constitutional status of an allegedly obscene work must be determined on the basis of a national standard. It is, after all, a national Constitution we are expounding.”53 It had been three years almost to the day since Grove had first issued Tropic of Cancer, and over that brief period Rosset had not only revolutionized the publishing industry but had also mobilized a cadre of publishers, academics, and artists in a successful effort to transform the cultural field itself by incorporating the literary underground into the mainstream.

Although the copyright to Tropic of Cancer was, as Rosset testified in the Chicago trial, “clouded,” and Grove had rushed out a Black Cat paperback version in late 1961 to compete with anticipated pirated editions, the version that rocketed to the top of the bestseller lists in the early 1960s, with a copyright granted to Grove Press, has remained remarkably stable across time, and Miller’s books, enormously popular and critically acclaimed throughout the 1960s, remain reliable titles on Grove’s backlist. Featuring a gushing introduction by Karl Shapiro celebrating Miller as “the greatest living author,” a laudatory preface by Anaïs Nin (rumored to have been penned by Miller himself) promising that his book “might restore our appetite for the fundamental realities,” and issued originally with a tastefully unadorned cover, Grove’s version of Tropic of Cancer made it into the margins of the modernist canon and onto reading lists at colleges and universities across the country, as Miller had dismissively told Rosset it would. Although Grove chose not to incorporate any trial transcripts or legal decisions into the text itself, it was able to further capitalize on the controversy a few years later when it published E. R. Hutchison’s study, Tropic of Cancer on Trial: A Case History of Censorship, which had started out as a dissertation at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The 1960s were Miller’s decade, as Grove was finally able to publish both the Tropics and his Proustian magnum opus, The Rosy Crucifixion. And they sold well; in June 1965, Miller occupied the top four positions on the New York Post’s bestseller list, and he remained on bestseller lists across the country for the remainder of the decade. Tropic of Cancer alone eventually sold more than 2.5 million copies in Grove’s mass-market edition. Furthermore, something of an academic industry emerged around his work, as professors and critics strove to legitimate and account for his popularity. One of the more influential of these, Ihab Hassan of Wesleyan University, in his 1967 study The Literature of Silence: Henry Miller and Samuel Beckett, proudly proclaims, “Henry Miller, who has survived both Faulkner and Hemingway, is finally honored in his country.”54 Hassan celebrates Miller as “the first author of anti-literature,” and he explains Miller’s use of obscenity in illuminating terms: “In his work, the physical body of men and women is anatomized only to be finally transcended; obscenity is a voice of celebration. Obscenity is also a mode of purification, a way of cleansing human sensibilities from the sludge of dogma, the dross of hypocrisy.”55 Hassan’s section on Miller, “Prophecy and Obscenity,” renders Miller’s work in an apocalyptic frame, illustrating that, in the 1960s, the aesthetic transgressions of the avant-garde were increasingly understood in political terms. Indeed, Hassan opens his study, which significantly twins Miller and Beckett as “the two masters of the avant-garde today,” with the proclamation that “criticism may have to become apocalyptic before it can compel our sense of relevance.”56 As a member of the cultural wing of the newly expanded and diversified professional managerial classes, Hassan can be seen as a spokesman for the cadre of critics and writers that canonized the cultural coordinates of the New Left’s political agenda.

As the litigation over Tropic of Cancer was proceeding across the country, thousands of copies of Naked Lunch were languishing in the Grove Press warehouse on Hudson Street. Though the perennially impecunious Girodias was pressuring him to distribute it, Rosset wanted to wait until the litigation over Miller died down. Anticipation over Naked Lunch in countercultural circles had been growing since the publication of portions in the Chicago Review in 1958 had earned the censure of the University of Chicago administration, prompting editor Irving Rosenthal to found the journal Big Table expressly to publish the offending excerpts. The Post Office impounded the first issue of Big Table, prompting a trial whose eventual success inspired Girodias to publish the novel in Paris. Rosset published excerpts in the Evergreen Review in 1961, and then, buoyed by Burroughs’s critical coronation at the Edinburgh Writers’ Conference organized by John Calder in August 1962, Grove brought out its hardcover edition. In early 1963, a Boston bookseller was arrested for selling the book, and Rosset retained the services of Edward de Grazia to defend him. As with the earlier cases, they closely followed the precedents from Ulysses, soliciting an impressive panel of experts, including John Ciardi, Norman Mailer, and Allen Ginsberg, to substantiate that Burroughs’s book was a “modern classic.” Although the case was originally in personam against the bookseller, De Grazia had it changed to in rem against the book, ensuring that the expert testimony would focus on the text itself.

As was not the case for Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Tropic of Cancer, it proved challenging to find experts who could establish an authoritative version or interpretation of Naked Lunch. The prosecuting attorney, William Cowin, understandably doubted that it had a structure as coherent and intentional as that of Ulysses. Thus, he asked the first expert witness, John Ciardi, “When he put these notes or writings, however you would refer to the book, together, do you feel that he knew what he was doing; that he was conscious that he was actually writing this book called NAKED LUNCH?”57 After all, the first Grove edition begins with “Deposition: Testimony concerning a Sickness,” in which Burroughs claims, “I have no precise memory of writing the notes which have now been published under the title Naked Lunch.”58 As one early critic affirmed, the challenge of the defense in this trial was to “prove to the court’s satisfaction that Naked Lunch is a book.”59

As in the cases of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Tropic of Cancer, Grove solicited a revealing combination of literary and sociological experts for the trial of Naked Lunch. In addition to Ciardi, Mailer, and Ginsberg, De Grazia retained Paul Hollander, a newly hired assistant professor of sociology at Harvard specializing in deviance and delinquency. Hollander claimed to be the first professor to offer a sociology of literature course at Harvard. Thus, his defense of Naked Lunch was based on sociological rather than aesthetic value: “From the point of view of the sociology of literature specifically, I think the book has merit because it presents a social type or a segment of society or subculture . . . So, in so far as the sociology of literature seeks to understand society via or through novels, this book is informative.” He then goes on to clarify: “The world he presents is an underworld, a subculture alienated from and contemptuous of the norms, values and standards of society at large. People who belong to this underworld consciously or unconsciously, deliberately and spontaneously, are engaged in flaunting these standards and norms.”60 Hollander’s contention that literature that accurately reflects subcultural and countercultural experience has a sociological value independent of its literary merit became central to Grove’s legitimation of many of its books in the later 1960s.

In the end, neither the aesthetic nor the sociological argument convinced the judge in the Boston trial, who found the text obscene, claiming that “the author first collected the foulest and vilest phrases describing unnatural sexual experiences and tossed them indiscriminately” into the book.61 His ruling was overturned upon appeal, but only because the US Supreme Court had, in the intervening months, clarified that a text could be suppressed only if it was “utterly without redeeming social value.” The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court was forced to concede that “it appears that a substantial and intelligent group in the community believes the book to be of some literary significance,” and therefore it could not be deemed obscene.62

Rosset used these expert opinions, as well as the ultimate decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, to leverage sales of Naked Lunch, as he had done with Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Tropic of Cancer. In a 1962 letter to booksellers he compares Naked Lunch to “other famous modern classics of American and English literature—including James Joyce’s Ulysses, D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Henry Miller’s Tropics”—and then quotes a series of critics and authors justifying the comparison.63 Grove also published excerpts from the trial transcript in the June 1965 issue of Evergreen Review and included them, along with the Massachusetts Supreme Court decision, as front matter in the Black Cat mass-market edition issued in 1966, by which time the hardcover had sold more than fifty thousand copies. By November 1966, the mass-market edition had reached number 1 on the New York Post’s bestseller list.

The excerpts incorporated into this volume do not include the exchanges with the academic experts who testified at the trial. They focus instead on the testimony of Norman Mailer, who along with Mary McCarthy had been championing Burroughs ever since the Edinburgh Festival, and Allen Ginsberg, without whose editorial and promotional efforts Burroughs would probably never have been published. Mailer affirmed that Naked Lunch was “a deep work, a calculated work, a planned work” that drew him in “the way Ulysses did when I read that in college, as if there are mysteries to be uncovered when I read it.”64 And Grove recycled Mailer’s laudatory claim that Burroughs is “the only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius,” originally quoted on the back of the hardcover edition, for the front of the paperback.

But Ginsberg’s testimony indicated the transformation that had been wrought in American literary culture in the few years since the case of Lady Chatterley. By now the author of “Howl,” which had been the first work of literature to be exonerated of charges of obscenity based upon the legal reasoning in Roth, was an international celebrity with credentials of his own, which he simply affirmed by noting, “I am a poet and have published.”65 The judge clearly thought that Ginsberg, in sandals and a three-piece suit, was the only person in the courtroom who might conceivably understand what Naked Lunch was about, and he plied him with questions about the political and sexual themes of the text, particularly as they are laid out in the section on the parties of Interzone. Ginsberg’s expertise as a poet, not a scholar, was ratified when De Grazia asked him, “Didn’t you once write a poem about Naked Lunch?” Ginsberg answered, “Yes, a long time ago.” De Grazia asked Ginsberg if he had the poem with him, and Ginsberg answered that he did and that it appears in “a book of my own that is called Reality Sandwiches.” The judge then asked where he might find the book, and Ginsberg answered, “Probably in Cambridge.” Ginsberg concluded his testimony by reading aloud “On Burroughs’ Work,” a poem he had composed well before much of Naked Lunch had even been written, affirming that both his testimony and his poetry had achieved enough cultural legitimacy for De Grazia to solicit it and for Grove to republish it as part of the proliferation of paratexts that continued to grow around this novel.66

Mailer’s and Ginsberg’s presence as expert witnesses in the trial of Naked Lunch indicates the ascendancy of the generation that had been educated by the literary experts who had canonized modernism in the postwar American university. Mailer had studied with Robert Gorham Davis at Harvard; Ginsberg, with Lionel Trilling at Columbia. Both writers had modeled their iconoclasm on modernist innovators while simultaneously decrying their domestication by academic critics such as Davis and Trilling. Both men, in other words, wanted to translate the subversive energies of literary modernism into the political and sexual realm. The publication of Naked Lunch, a text that radically combined aesthetic innovation with sexual explicitness and political allegory, seemed to indicate the triumph of this vision.

Lawrence, Miller, and Burroughs all ended up on bestseller lists, and Grove’s net sales for 1964 came to more than $1.8 million; but due to the extensive costs of litigation, the company was still operating at a loss. Nevertheless, Rosset decided to expand and moved to larger quarters at 80 University Place. Rosset and Jordan also decided to change the format of the Evergreen Review from a quarterly quarto to a bimonthly, and then monthly, folio-size magazine with glossy (and frequently racy) covers and a wider diversity of advertisers, emphasizing book, record, tape, and poster clubs, as well as cars, cruises, clothes, and alcohol. According to Rosset, he and Jordan initiated the format change because they “felt that there ought to be a larger audience for what we were doing. We’d reached a plateau in circulation in the small size, about twenty thousand an issue, and nothing we did managed to break through that ceiling.” The quarto format was helpful initially because “we were able to confuse the bookstores as to what we were. We were treated both as a book and a magazine—we got the best of both worlds. But it kept us within a certain circle. You didn’t get into the world of big, real magazines.”67 By 1964, the colophon was well established in bookstores and college classrooms; it was time to move on to newsstands, to take it to the streets.

In his announcement of the change to subscribers, Jordan notes that the magazine has been redesigned by Roy Kuhlman, “one of America’s best-known graphic artists,” and will feature “drawings, collages, and many beautiful photographs (in color as well) to add to its new visual excitement.” Indeed, Evergreen Review 32 featured a portfolio of erotic photographs by Emil Cadoo that solicited the censorious wrath of the Nassau County district attorney, garnering additional publicity for the launch of the new format (Figure 24). Jordan continues, “To inaugurate the new format, we have put together what is without a doubt the finest, most adventurous collection of modern writing to be found anywhere between the covers of a magazine.”68 This issue did contain an impressive roster of writers, most of whom were already closely associated with the magazine, including Jean Genet, William Burroughs, Norman Mailer, Michael McClure, Robert Musil, Jack Gelber, and Eugène Ionesco. It also featured a full-page ad for a new anthology edited by LeRoi Jones, The Moderns: An Anthology of New Writing in America. Although not published by Grove, the collection features a significant number of its authors, including Jones, Kerouac, Burroughs, John Rechy (whose City of Night had rocketed to the top of the bestseller lists in the preceding year), and Hubert Selby (whose Last Exit to Brooklyn Grove had just released in hardcover). The ad copy announces that “the significance of the literary upheaval that has been taking place in the United States over the last decade is just beginning to be realized. A new young group of writers has been at work creating an American fiction that is completely separate from the fashionable literary world.”69 The magazine also features full-page ads for Yale University Press’s edition of Cleanth Brooks’s study of William Faulkner, for Grove’s own publication of Beckett’s How It Is, for Riverside Records’ LP of Bentley on Brecht, for Paul Goodman’s novel Making Do, and for the New York Review of Books, the Paris Review, and the Tulane Drama Review, featuring a special supplement on the Living Theatre. As this ad copy indicates, by 1964 Grove had become central to the simultaneous popularization and institutionalization of modernism in the United States.

Figure 24. Cover of Evergreen Review after change in format (1964). (Photograph by Emil Cadoo)

The modernism Grove promoted, as is so abundantly illustrated in the testimony at the obscenity trials of Lawrence, Miller, and Burroughs, solicited both elite and populist modes of legitimation. On the one hand, Grove relied heavily on the testimony of academic experts, depending on modernism’s reputation for difficulty and complexity. On the other hand, Grove promoted the more populist proclamations of authors such as Miller and Burroughs, who were disdainful of academic expertise. The shift from freedom of expression to freedom to read, and the oscillation between literary and sociological testimony in these trials, reveals this tension, which was so central to the transitional location of modernism in the 1960s.70 The cultural torque of this tension derived from the unprecedented sexual explicitness of these texts, which increasingly came to characterize avant-garde writing in this period. For this reason, I choose to call this developing canon of late modernism “vulgar modernism,” both for its vernacular aspirations and for its erotic preoccupations. More than any other postwar publisher, Grove was responsible for putting vulgar modernism on the literary map.71

It was a modernism dominated by men. As the trajectory from Lawrence to Miller to Burroughs economically illustrates, Grove’s battle against censorship began with a quintessentially high modernist preoccupation with adulterous women—inaugurated by Madame Bovary and Ulysses—and ended up with the highly homosocial and increasingly homosexual preoccupations of late modernist figures such as Burroughs and Jean Genet. When Grove began to publish Genet’s homosexually explicit autobiographical novels, he had long been a hero to the Beats, and the popularity of his prose in the 1960s buttressed Grove’s centrality to the realignment of postwar American masculinity. All of Genet’s novels take place within homosocial institutions and networks—reform schools, prisons, the criminal underworld—and his overwrought stylization and spiritualization of these milieus helped provide a cultural consecration for the boy gang as dissident literary community in the United States.

Rosset had been interested in Genet since the early 1950s, but he cautiously began with the plays, waiting for a more permissive climate to bring out the far more homosexually explicit prose. Samuel Roth’s publication of a pirated version of Our Lady of the Flowers forced Rosset’s hand, and he had to proceed with publication earlier than he might have liked, beginning with an excerpt in the Evergreen Review in the spring of 1961. In the meantime, Bernard Frechtman had finished translating Sartre’s massive study, Saint Genet: Actor and Martyr, for George Braziller, and Grove arranged to bring out at the same time, in hardcover, Frechtman’s translation of Our Lady of the Flowers, with an ample excerpt from Sartre’s study as an introduction. Rosset negotiated with Braziller for cooperative advertising and joint reviews, ensuring that Genet’s novels would enter the United States in the existential embrace of postwar Europe’s most respected and influential intellectual.

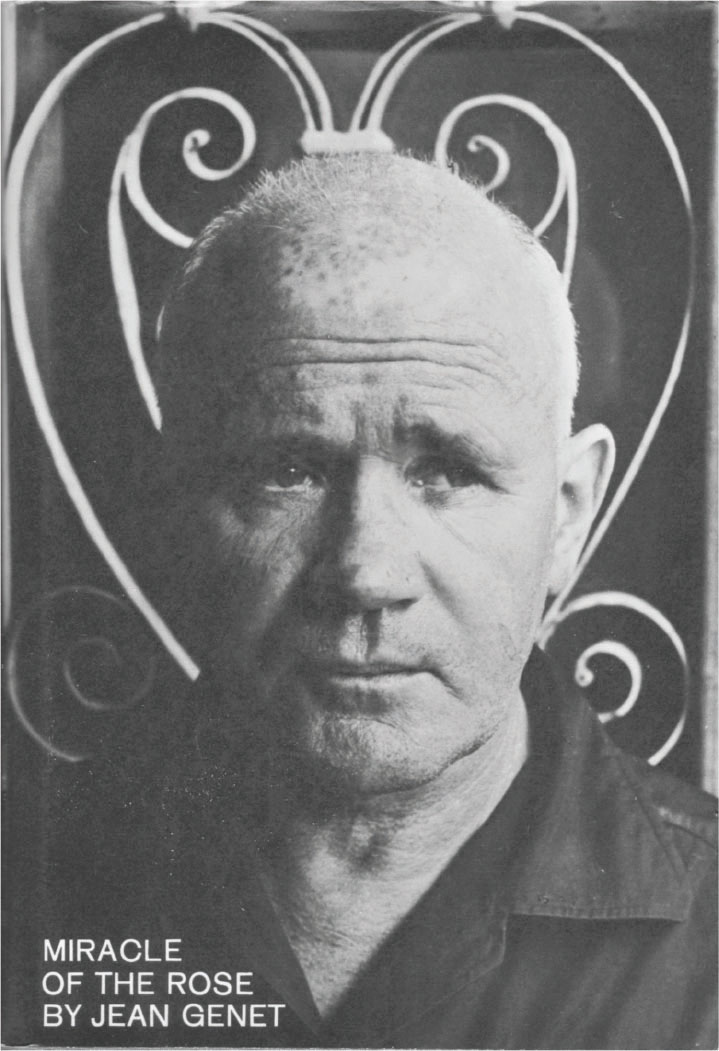

In essence, Saint Genet provided the “expert testimony” establishing that Genet’s work had redeeming social value. And American reviewers were happy to have Sartre’s philosophical help and cultural imprimatur in understanding these sexually explicit and formally difficult texts, which both celebrate and equate homosexuality and criminality as modes of aesthetic stylization and spiritual apotheosis. Saint Genet provided the philosophical vocabulary within which reviewers could situate its subject’s literary output, framing both (male) homosexuals and criminals as “others” to mainstream middle-class culture. Genet’s canonization in France, enabled by the patronage of Sartre and Cocteau, also helped reviewers situate him within a lineage of French poètes maudites, from Baudelaire to Rimbaud to Villon to Céline, providing further cultural cover for his sexually dissident identity. Grove continued to issue Genet’s novels, initially in hardcover, over the course of the 1960s: The Thief’s Journal, with a brief foreword by Sartre, in 1964, and then Miracle of the Rose in 1966. The book jacket for Miracle of the Rose features Genet’s face framed by an iron grillwork that simultaneously suggests horns, a heart, and a headdress, an overdetermined image that distills the moral and political complexity of his canonization in the United States, where he was embraced by the counterculture and the political left (Figure 25).

Genet’s novels considerably exaggerate his criminality, and it is worth remembering that the crime for which he almost spent his life in prison and for which he was pardoned by the French president in 1948, was stealing books from the quays along the Seine.72 Many, if not most, of Genet’s convictions were for book theft, which complements and complicates the circuits through which his own writing passed. Our Lady of the Flowers was, as Grove’s flyleaf reminds us, originally written on the paper prisoners were given to make bags, and its characterizations were partly inspired by the pulp fiction Genet read as a boy. Until Gallimard published it in 1951, it was available only in limited, or pirated, editions and translations, its value inversely elevated by the criminal depths from which it emerged. In 1963, Grove’s hardcover hit number 3 on the New York Post’s bestseller list; by 1967, it was in its fourth printing as a Bantam mass-market paperback; and by 1968, Bantam reissued it as a Bantam Modern Classic, marking Genet’s successful, and indeed symptomatic, migration from the margins to the mainstream.

Grove’s championing of authors such as Miller, Burroughs, Genet, Rechy, and Selby indicates the homosocial contexts in which most of the postwar struggles against censorship were initially negotiated. As Michael Davidson affirms, the literary communities that formed around the New York school, the San Francisco Renaissance, and the Beats exacted a “compulsory homosociality” that tended to exclude women but resolutely permitted, indeed required, acceptance of male homosexuality, rendering the traditionally rigid boundaries between heterosexual and homosexual orientation more fluid.73 Davidson focuses on postwar poets, but the male-dominated author list and institutional organization of Grove Press reveal that this fraternal ordering of social relations characterized the countercultural publishing world as well. Grove embraced gay male writers and readers, publishing Spicer, O’Hara, Ginsberg, and many other openly gay authors in the Evergreen Review, and heavily promoted the work of John Rechy, whose semiautobiographical novels City of Night and Numbers chronicle the life of a male hustler with unprecedented explicitness. Grove’s publication of these authors, and its active address to their audience during a time when homosexuality was still illegal across the United States, was a crucial component of its battle against literary censorship. Two novels, Rechy’s City of Night and Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, illustrate Grove’s centrality to this realignment of US masculinity.

Figure 25. Kuhlman Associates’ cover of The Miracle of the Rose (1966).

(Photograph by Jerry Bauer)

City of Night was a landmark in publishing, laying the groundwork for the emergence of gay literature as a lucrative market niche in the 1970s. Don Allen linked Rechy up with Grove in 1960 and provided crucial editorial assistance and emotional support to the young author in completing his first book. It became Grove’s fastest-selling novel ever, enjoying six months on the New York Times’s bestseller list in 1963 and at one point selling more than one thousand copies per day. Grove aggressively pursued an international market, selling translation rights to publishers in France, Germany, Denmark, Portugal, Japan, Spain, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Israel, and Poland.

Despite the novel’s homosexual focus, Rechy rejected Kuhlman’s suggestion that the cover feature a picture of a drag queen without title or author. As Rechy wrote to Seaver, “I want, very much, for this book of mine to be presented as a very serious work, shunning as far as possible any strong emphasis on it as a sensational exposé.”74 He further affirmed that he didn’t want the jacket copy to categorize it as a “homosexual novel,” writing later to Seaver, “My objection to the word ‘homosexual’ on the jacket is merely a reaction to it as much too clinical; and, really, much too explicit and restrictive regarding the book itself . . . Would ‘sexual underworld’ or ‘sexual underground’ or ‘the world of subterranean sex’ do just as well?”75 Rechy’s reservations situate his novel in the pre-Stonewall era, before the uprising that, among other things, made gay literature a mainstream marketing category, but they also illustrate the appeal of the underground as a cultural region in which such distinctions are less important, at least between men. Grove exploited these connotations of the term “underground” quite successfully in the later 1960s.

Rechy may not have wanted his novel to be promoted as “homosexual,” but he couldn’t prevent reviewers from perceiving it in those terms, nor is it surprising, given the book’s focus, that they did. Peter Buitenhuis, in his review for the New York Times, opens by announcing, “This novel would surely not have been published as little as five years ago. Its issue by a reputable house marks how far the black hand of censorship has been lifted.” But Buitenhuis sees no literary value in Rechy’s narrative, calling him “an inept writer with a number of mannerisms that should have been suppressed by an editor.” Rather, echoing Hollander’s testimony in the trial of Naked Lunch, Buitenhuis recognizes the novel’s sociological value, claiming it has “the unmistakable ring of candor and truth,” and dubbing Rechy “the Kinsey of the homosexuals.”76 Rechy struggled against this pigeonholing, but Grove marketed him in the 1960s as a chronicler of the homosexual world. The cultural visibility of his books, and others published by Grove, provided an opening cultural wedge for the Stonewall riots of 1969, in which, as historian David Carter argues, “the most marginal groups of the gay community fought the hardest.”77

A more aesthetically representative example of the vulgar modernism Grove helped establish in the 1960s was Hubert Selby, whose sensationally explicit Last Exit to Brooklyn Grove published in hardcover in 1964. Born and raised in Brooklyn and a close childhood friend of Gilbert Sorrentino (soon to become an assistant editor at Grove), Selby had little formal education but nevertheless developed a distinctive stream-of-consciousness style whose modernist antecedents were clear. Indeed, if Miller was the Brooklyn Proust, than Selby was its Joyce, and Last Exit, which vividly and clinically depicts the most marginal and desperate denizens of Manhattan’s notorious neighbor, something of a latter-day Dubliners.

Explicit as it was, Last Exit to Brooklyn escaped censorship in the United States (though there was a landmark trial in Britain later in the decade); its unimpeded entry into the literary marketplace testifies to the remarkable transformation Grove had precipitated with the series of trials that preceded its publication. Furthermore, insofar as it positions the criminal underworld of Brooklyn against the sexual underground of Manhattan, it can be understood as an indigenous psycho-geographic map of Grove’s vulgar modernist sensibilities. The reigning character in this landscape was the Queen, the central subject of Selby’s second chapter, “The Queen Is Dead,” which was also the lead story in Evergreen Review 33 in 1964. Edmund White credits Jean Genet with “the literary creation of the Queen, a creature who had existed only in folklore before Genet wrote his portrait of Divine” in Our Lady of the Flowers.78 And Genet is specifically named by Selby’s title character, Georgette, who “took a pride in being a homosexual by feeling intellectually and esthetically superior to those (especially women) who werent gay.”79 When Genet is mentioned, Georgette’s love object, a Brooklyn ex-con named Vinnie, asks, “Whose this junay?” to which Georgette replies, “A French writer Vinnie. I am certain you would not know of such things.”80 “Such things” are precisely what made up the literary repertoire of the homosocial networks in which vulgar modernism circulated and that were in turn both chronicled and aestheticized by its principal avatars. The party that concludes “The Queen Is Dead” provides a set piece for this milieu, when Georgette recites Poe’s “The Raven” to the accompaniment of a Charlie Parker record, at which point everyone at the party “knew she was THE QUEEN.”81

The Queen’s literary ascendance in the social circuits of vulgar modernism is further affirmed in the long story that forms the centerpiece of Last Exit to Brooklyn, “Strike,” which chronicles the experiences of a Brooklyn lathe operator and shop steward named Harry during a strike at his factory. The story is less concerned with the strike itself than with the idleness the strike enables, allowing Harry to take up with a transvestite named Alberta. The contrast between the opening sex scene with his wife, with “Harry physically numb, feeling neither pain nor pleasure, but moving with the force and automation of a machine; unable now to even formulate a vague thought, the attempt at thought being jumbled by his anger and hatred,” and the later sex scene with Alberta, where he experiences “the sudden overpowering sensation of pleasure, a pleasure he had never known, a pleasure that he, with its excitement and tenderness, had never experienced,” reveals the utopian extensions of vulgar modernism’s homosocial preoccupations.82 These scenes, one in which a drag queen recites a poet canonized by Baudelaire to the tune of a bop saxophonist canonized by the Beats and the other in which a Brooklyn shop steward has his first experience of sexual fulfillment with a Manhattan transvestite, provide some of the contradictory cultural coordinates within which vulgar modernism briefly flourished.

And its time was brief. The principal authors Grove brought to the forefront in its battle against censorship—Lawrence, Miller, Burroughs, Genet, Rechy, Selby—received both critical and popular acclaim during the 1960s, but, with the notable exception of Burroughs, they are rarely taught or written about today. Rather, vulgar modernism emerged in the brief interregnum between high modernism and postmodernism, between the end of obscenity and the rise of pornography, as a transitional formation specific to the 1960s.

In 1966, the US Supreme Court took up the case of Putnam’s publication of John Cleland’s eighteenth-century pornographic novel Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, which had been appealed along with Mishkin v. State of New York and Ginzburg v. United States. On March 21, Cleland’s famous book was exonerated, but Ginzburg’s and Mishkin’s guilty verdicts were affirmed. The reasons for this split are informative. While Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, like Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was being rescued from illicit underground circulation by a reputable publisher, Ralph Ginzburg and Edward Mishkin were pariah capitalists in the tradition of Samuel Roth, who had also been found guilty in the landmark case that bears his name. In affirming their guilty verdicts, the high court determined, in an argument similar to Earl Warren’s reasoning in his Roth concurrence, that it “may include consideration of the setting in which the publications were presented as an aid to determining the question of obscenity.”83 The court decided, in other words, that a text’s location in the cultural marketplace was relevant to determining whether or not it could be deemed obscene; if the publisher marketed it as obscene, the court would be more likely to agree. Although this “pandering” logic was maligned at the time, it was in essence an acknowledgment that the literary underground in which pirated masterpieces had circulated alongside pornographic pulp was coming to an end. Grove Press had successfully legitimated even the most explicit and graphic texts; men like Roth, Ginzburg, and Mishkin were no longer necessary.

The 1966 decision was an important step in the court’s shift from an “absolute” to a “variable” definition of obscenity over the course of the 1960s, a shift that was particularly significant in the court’s acceptance of a lower threshold when judging the legality of materials made available to minors. Following the logic elaborated by William Lockhart and Robert McClure in their influential article for the Minnesota Law Review, the court, realizing the difficulty of establishing a fixed definition of obscenity, was beginning to formulate a more flexible definition based on the audience to which the materials were directed. The most important consequence of this shift was the emergence of a relatively unrestricted “adult” market for sexually explicit materials, a market whose social and cultural legitimacy Grove helped establish.84

Thus, the split decision in 1966 put Mishkin and Ginzburg in jail, but it provided Rosset, whose reputation was at its peak, with the opportunity to move in on their turf, legally and profitably exhuming the entire literary underground of the modern era. Grove almost single-handedly transformed the term “under ground” into a legitimate market niche for adults in the second half of the 1960s, starting with a campaign inviting readers to “Join the Underground” by subscribing to the Evergreen Review and by joining the Evergreen Club, which Rosset had started earlier that year as a conduit for distributing Grove’s rapidly expanding catalog of “adult” literature and film. By specifying its audience as “adult,” by continuing to emphasize its literary credentials, and by concentrating its more explicit materials in the institution of a book club, Grove was able to turn the court’s pandering logic to its advantage. Rosset dealt in the same wares as Ginzburg and Mishkin, but the combination of Grove’s literary reputation and the restricted audience enabled by the club prevented him from suffering their fate.

In the opening months of 1966, “Join the Underground” appeared in full-page ads in Esquire, Ramparts, New Republic, Playboy, the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, and the Village Voice and on posters throughout the New York City subway system. Grove also distributed tens of thousands of free stickers to subscribers that began to appear on public benches and in public bathrooms across the country. The ad in the Times opens by provocatively specifying its target demographic: “If you’re over 21; if you’ve grown up with the underground writers of the fifties and sixties who’ve reshaped the literary landscape; if you want to share in the new freedoms that book and magazine publishers are winning in the courts, then keep reading. You’re one of us.”85 The ad chronicles how Grove spearheaded this transformation, from the court battles over Lawrence and Miller to its promotion and publication of the theater of the absurd and the French New Novel. In order to entice the audience expanded by its efforts to join the club and subscribe to the magazine, Grove offered a free copy of one of three titles: Eros Denied by Wayland Young, “which examines the awful mess the Western World has made of sex”; Games People Play by Eric Berne, the surprise bestseller that promises to “give people astonishing insights into parts of their lives they usually keep hidden”; and Naked Lunch, described as “an authentic literary masterpiece of the 20th century that has created more discussion, generated more controversy, and excited more censors than any other novel of recent times.” The campaign was a big success, as Seaver reported to Harry Braverman: “The response by the Evergreen subscribers to the book club mailing has been overwhelming, and the full page advertisement in the New York Times last Sunday is going to produce at least 1500 members—an unheard of response.”86

Buoyed by the success of the campaign—circulation for the Evergreen Review had nearly doubled from fifty-four thousand to ninety thousand in the first half of 1966—Jordan commissioned Marketing Data, Inc., that summer to distribute a survey to Evergreen Review subscribers. The survey established that, according to an article in Advertising Age, “the average member of the ‘underground’ is a 39-year-old male, married, two children, a college graduate who holds a managerial position in business or industry, and has a median family income of $12,875.”87 Jordan promptly mounted a follow-up campaign, boldly asking readers, “Do you have what it takes to join the Underground?” The ad prominently displays the survey results and then answers, “You have what it takes if you need what we’ve got: a collection of readers who are better educated than Time’s; better off than Esquire’s; and holding down better jobs than Newsweek’s.” It concludes, “All in all, the Underground magazine looks like it’s going through the roof. Take a look at the charts above taken from our recently completed reader survey.”88 Although the promotional copy doesn’t mention it, the first survey statistic reveals that Evergreen’s subscriber base was 90 percent male, affirming that the homosociality of Grove’s literary and cultural network extended into its readership.

To these well-paid, well-educated, and predominantly male readers, adjacent to and interested in the countercultural communities that remained Evergreen’s core constituency, Grove channeled much of its catalog in the later 1960s, a catalog that was increasingly ballasted by pornography and erotica exhumed from the Edwardian and Victorian undergrounds. Rosset’s sources for this material were many. He continued to plunder the Olympia backlist, including reissuing the Traveler’s Companion series and an Olympia Reader, edited by Girodias, who had declared bankruptcy and moved to New York City in order, he hoped, to exploit the new freedom enabled by Grove. Rosset also acquired many titles from a private collector named J. B. Rund, whose interest in erotica and pornography began when he worked in Grove’s mailroom.

Rosset also purchased many titles from Phyllis and Eberhard Kronhausen, sex therapists and erotica collectors with whom he worked closely in the late 1960s (and who were affectionately known in the Grove offices as “Syphilis and Everhard”). The Kronhausens, who were prominently profiled by Sara Davidson in Evergreen Review 15, no. 91, published a variety of books with Grove, including The Sexually Responsive Woman (1964), Walter, the English Casanova (1967), and Erotic Fantasies (1969). They used their royalties from these and other books to collect erotic art from around the world, mounting a triumphant international exhibition at museums in Denmark, Sweden, and Germany in the summer of 1968. Grove published two lavishly illustrated volumes based on the exhibition.

In the late 1960s, Grove reissued in popular editions virtually every title whose publication had previously been forbidden by Comstock-era laws, thereby transforming the structure of the cultural field. In effect, Grove brought Francophone and Anglophone materials whose value had been based in their rarity into mainstream American print circulation, briefly achieving a considerable cash infusion for the company that would, in the end, only hasten its decline.89

Lauded by legendary literary luminaries Charles Baudelaire and Guillaume Apollinaire, the wildly explicit writings of Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade had been understood as the secret subterranean source of the amorality of modernism since its inception. But Sade’s work had been unavailable legally in both the Francophone and Anglophone literary marketplaces until the postwar era. Before then, Sade’s unavailability buttressed his mystique: simply having read him could indicate membership in an exclusive club. As part of its effort to popularize modernism, it was inevitable that Grove would publish Sade.

Indeed, Rosset’s interest in Sade went back to the beginnings of Grove, when he published a carefully sanitized selection of his writings, chosen and translated by Paul Dinnage as an “anthology-guidebook,” prefaced by Simone de Beauvoir’s now-classic essay from Les temps modernes, “Must We Burn Sade?” Published in hardcover in May 1953, Grove’s selections followed Edmund Wilson’s lengthy New Yorker article of 1952, “The Vogue of the Marquis de Sade,” which deprecated the hagiographic bias of foundational Sade scholars Maurice Heine and M. Gilbert Lely (whose biography of Sade Grove later published) but praised Beauvoir’s essay as “perhaps the very best thing that has yet been written on the subject.”90 Wilson declined to write an introduction for the volume but agreed to let Grove use his article in its promotional efforts. Although the more explicit sections were left in the original French, Grove nevertheless promoted the volume in its press release as “one of the first attempts to make available in English large selections of what the Marquis actually wrote.”91 Sporting an untranslated epigraph from Baudelaire’s Journaux intimes exhorting the reader, “Il faut toujours revenir a de Sade, c’est-à-dire a l’homme naturel, pour éxpliquer le mal” (We must always go back to Sade, that is, to the natural man, to understand evil), and concluding with a chronology and bibliography compiled by Dinnage, this small volume anticipates the scholarly seriousness with which Grove published Sade in the 1960s.

In the same year that Grove issued this sanitized collection, Austryn Wainhouse, using the baroque pseudonym Pieralessanddro Casavini, published his unexpurgated translation of Justine with the Olympia Press. Over the next decade Wainhouse, a Harvard graduate on what became permanent leave from his doctoral studies at the University of Iowa, translated a large selection of Sade for Girodias under this pseudonym. These translations became the foundation for the massive three-volume, two thousand-plus-page edition of Sade’s work that Wainhouse and Seaver, who had originally met as members of the Merlin collective, assembled for Grove in the mid-to late 1960s, after the risk of censorship had been eliminated by the successes with Lawrence, Miller, and Burroughs.