|

Reading Revolution |

|

Reading Revolution |

In 1961, Grove reprinted Edgar Snow’s classic text Red Star over China, originally published to great acclaim by Random House in 1938, as the eighth title in its newly inaugurated Black Cat mass-market imprint. Snow’s hagiographic, and ultimately prophetic, history of the struggles of the Chinese Communists had been a formative influence on Barney Rosset. When he was stationed with the Army Signal Corps in China during the war, Rosset had Snow’s text with him and, based on his reading of it, felt himself to be the only American who knew that the Communists would prevail. The front matter for the Black Cat edition classifies Red Star over China as “one of the basic source books of modern Chinese history, as a satisfying and enlightening tale for the general reader, and even as a handbook of guerilla warfare during World War II for anti-Nazi partisan fighters in Europe and anti-Japanese guerillas in Southeast Asia.” In his preface to the 1944 edition, Snow had commented on the global audience for his book, which offered English-speaking readers “an entirely new conception of Chinese character” while providing practical political guidance for resistance movements in India, Burma, and Russia. He further noted that the Chinese translation was widely pirated, with “many editions produced entirely in guerilla territory,” a testimony to Mao’s shrewdness in allowing Snow exclusive access to himself and the northwestern region of China held by the Communists after the legendary Long March.1 Red Star over China is a rare example of a book that intervened in the historical process it chronicled, and in that sense it can be seen as a model for the “revolutionary handbooks” Grove published in the 1960s.

As civil rights gave way to Black Power, the Vietnam War radicalized the New Left, and independence movements and student uprisings swept the globe, Grove issued a variety of titles billed as “handbooks” for revolutionaries, including Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth; Régis Debray’s Revolution in the Revolution?; Che Guevara’s Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War; Robert Lindner’s The Revolutionist’s Handbook; David Suttler’s IV-F: A Guide to Draft Exemption; Tuli Kupferberg and Robert Bashlow’s 1001 Ways to Beat the Draft; Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) radicals Kathy Boudin, Brian Glick, Eleanor Raskin, and Gustin Reichbach’s The Bust Book: What to Do until the Lawyer Comes; Julius Lester’s Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama!; and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as well as collections of speeches by Malcolm X, Che Guevara, and Fidel Castro. Like Red Star over China, these pocket-size paperbacks combined empirical evidence of with practical guidance for the attainment of revolutionary consciousness and the realization of revolutionary programs during a time when world revolution seemed imminent to many in the Movement.

Furthermore, in the second half of the 1960s, Grove expanded and enhanced both the investigative reporting and the radical rhetoric of the Evergreen Review, publishing double agent Kim Philby’s revelations about British and American intelligence; Ho Chi Minh’s prison poems; extensive reports on urban riots and ghetto activism; eyewitness accounts of the events of May 1968, the Democratic Convention in Chicago, and the trial of the “Chicago 8”; interviews with My Lai veterans and other exposés on the Vietnam War; and numerous articles by and about the New Left, Weather Underground, Black Panthers, and other revolutionary movements throughout the world. In these efforts, Grove sought to merge literary and political understandings of the term “avant-garde” in the belief that reading radical literature could instill both the practical knowledge and psychological transformation necessary to precipitate a revolution.

Also in 1961, Richard Moore, chairman of the Committee to Present the Truth about the Name “Negro,” issued a statement calling upon “intellectuals, writers, journalists, and leaders of important cultural and civic organizations of people of African descent to take decisive action on this question with full rather than ‘deliberate speed.’”2 Moore’s call was precipitated by Grove’s publication of the English translation of Janheinz Jahn’s groundbreaking study Muntu: The New African Culture, which opens with the affirmation, “We speak in this book . . . not about ‘savages,’ ‘primitives,’ ‘heathens,’ or ‘Negroes’ but about Africans and Afro-Americans, who are neither angels nor devils but people.”3 Muntu had become a bestseller at Moore’s Frederick Douglass Book Center in Chicago, and he hoped to speed this terminological reformation by capitalizing on its popularity among the burgeoning population of African American readers. As Donald Franklin Joyce affirms in his study of black-owned publishing houses in the United States, the era between 1960 and 1974 witnessed rapidly rising literacy rates and educational levels among African Americans, as well as increased government funding for public education and libraries in African American communities, expanding the economic viability and cultural autonomy of the black reading public.4 Grove endeavored to provide “revolutionary” reading for these radicalizing readers alongside the principally white counterculture that made up its primary audience throughout the 1960s.

As discussed earlier, Jahn had leaned heavily on the authority of Frantz Fanon in his introduction to Muntu, going so far as to offer a quotation from Black Skin, White Masks (unavailable in English at the time) as “a motto at the head of this book.” The quotation, appearing only a handful of pages after the excerpt cited by Moore, reads, “For us the man who worships the Negroes is just as ‘sick’ as the man who despises them. And conversely the black man who would like to bleach his skin is just as unhappy as the one who preaches hatred of the white man.”5 Although the English translation retains the term “Negro” for the French nègre, Jahn refers to Fanon himself as an “Afro-American” and offers Black Skin, White Masks as advocating the same cultural relativism that grounds his own analytical method. By the time Jahn finished Neo-African Literature: A History of Black Writing in 1966 (followed by Grove’s English translation in 1968), Fanon had posthumously become an international icon of African revolution and Jahn felt the need to engage his work more critically. In the final pages of this highly ambitious scholarly study, Jahn, this time discussing The Wretched of the Earth, argues that “Fanon’s analysis leaves no room for a free literature of independent writers.” Sticking to his cosmopolitan guns, Jahn warns his readers that “all purely psychological, political, or sociological interpretations . . . must always remain inadequate, for they neglect the aspect which makes literature what it is.”6

In 1970, S. E. Anderson reviewed Grove’s edition of Jahn’s study for the recently established journal Black Scholar. His opening paragraph illustrates the political and rhetorical transformations that marked the emergence of black studies in the United States: “Practically every brother and sister into a ‘black thing’ has read Jahn’s first book: Muntu. Many of us without question take Muntu as the gospel truth on black culture. Many of us even think that Janheinz Jahn is a brother!” Affirming that Jahn is indeed white, Anderson, a founding member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Arts movement and director of one of the first black studies programs in the nation, cautions that his scholarship, while constituting a useful resource, perpetuates “a dangerous dependency upon a white analysis of our existence.”7 Directly inverting Jahn’s statement in defense of his method, Anderson affirms that “it is in the realm of social and political analysis, not the interpretation of Neo-African styles and patterns, where Jahn fails.” Thus, he argues that “the conflict between Fanon and Jahn—and between the contemporary white critic and the revolutionary black writer—is that of understanding and dealing with the political and psychological components of black literature.”8 Anderson leaves no doubt where his allegiances lie, and while he concedes that Jahn’s work should be read by African Americans, he makes it clear that Fanon should guide their political practice, as well as their evaluation and understanding of the newly renamed “black writing.”

Grove published all of Fanon’s major work, enhancing the company’s reputation as a primary resource for revolutionary reading in the United States, and as with most of its international literature, Grove’s acquisition of Fanon was routed through Paris. The English translation of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon’s second book but in 1965 the first to be published in the United States, was originally commissioned in 1963 by Présence Africaine, the enormously influential Pan-African journal and publishing house founded in the late 1940s by Alioune Diop, for distribution in Anglophone Africa. Like the Algerian revolution on which the book’s conclusions are based, its publication was widely understood as a signal event in the proliferation of anticolonial wars and independence movements that were transforming the map of the world in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Wretched of the Earth features a preface from the ubiquitous Jean-Paul Sartre, whose imprimatur provided both cultural ballast and interpretive guidance for readers unfamiliar with Fanon’s work. Sartre’s famous preface, addressed specifically to “European” readers, affirms that the book is not addressed to white people and therefore must be read differently by them. In particular, Sartre exhorts his audience: “Have the courage to read this book, for in the first place it will make you ashamed, and shame, as Marx said, is a revolutionary sentiment.” For Sartre, all Europeans, including those descendants who occupy that “super-European monstrosity, North America,” are implicated in the colonial system that disqualifies them from membership in the intended audience of Fanon’s book.9 In its 1965 press release announcing the hardcover publication of The Wretched of the Earth in the United States, Grove emphasizes Sartre’s advice with an affirmation from LeRoi Jones that “Fanon’s book should be read by every black person in the world . . . Sartre’s introduction should be read by every white person.”10

The mainstream press took little notice when Grove brought out The Wretched of the Earth, with the New York Times restricting its coverage to a one-paragraph announcement headlined “Handbook for Revolutionaries.”11 Grove also placed ads in the Times, billing the book as “the handbook for a Negro Revolution that is changing the shape of the white world” and affirming that “its startling advocacy of violence as an instrument for historical change has influenced events everywhere from Angola to Algeria, from the Congo to Vietnam—and is finding a growing audience amongst America’s civil rights workers.”12 But it was the iconic Black Cat mass-market paperback, issued in 1968 and eventually selling more than 250,000 copies, that came to typify this quintessentially Sixties genre. Its design both invokes and obscures Sartre’s advice. The bottom half of Kuhlman’s famous cover features an uncredited photograph of a riotous crowd, partially transformed into an abstract ink blot by its reduction to high-contrast orange and black. The title above is glaring white, with the author’s name and the Black Cat colophon in green and the tagline “THE HANDBOOK FOR THE BLACK REVOLUTION THAT IS CHANGING THE SHAPE OF THE WORLD” in orange, linking it to the photo below (Figure 28). The back cover features Sartre’s exhortation from the preface—“Have the courage to read this book”—without including the audience qualification that follows. The back cover also features a blurb Grove solicited from Alex Quaison-Sackey, the first black African to serve as president of the UN General Assembly, affirming that the book “must be read by all who wish to understand what it means to fight for freedom, equality and dignity.” Grove’s paratextual packaging, then, helped establish a generic category—the revolutionary handbook—that it exploited over the course of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but it also generated a contradictory discourse about the practical use of such handbooks, especially regarding the racial identities of their readerships.

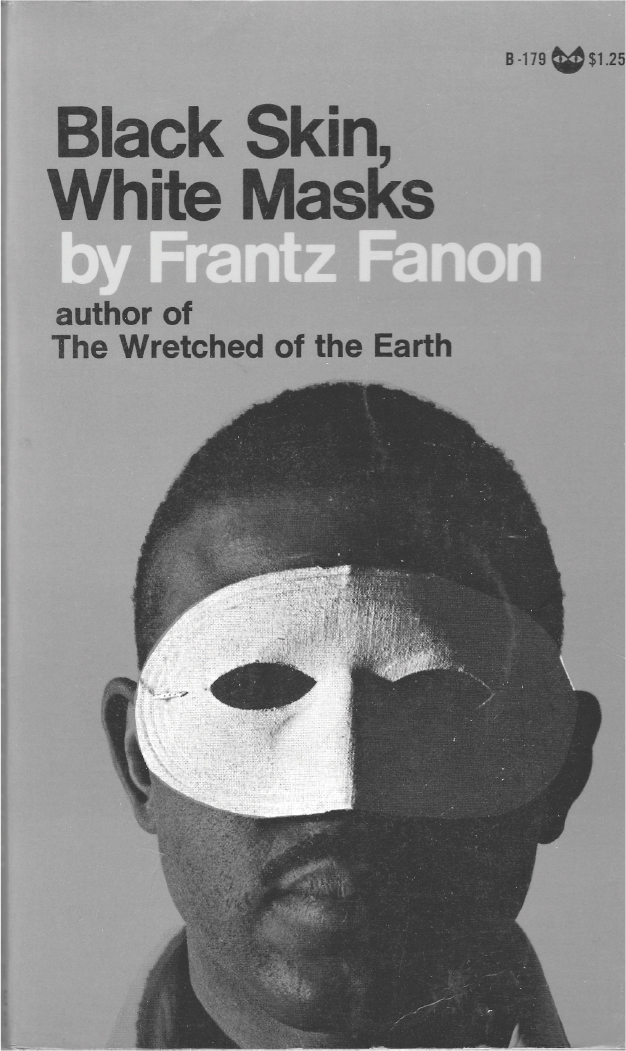

For the white readers who made up the bulk of its constituency, Grove offed Fanon as a source of insight into subaltern psychology, a tactic that was particularly, and somewhat embarrassingly, evident in its marketing of Black Skin, White Masks, published in 1967. The front cover of the Black Cat edition, issued the following year, invokes the imagery promulgated by the popular New York run of Jean Genet’s The Blacks: a photograph of an expressionless black man wearing a white mask over the upper half of his face, his eyes exposed but not visible, with only the right side of his face illuminated, leaving the left side in deep shadow. The background is brown and the title black, with the author’s name a lighter brown. Together, image and typography reflect the tension between abstract dualism and concrete multiplicity that tends to shadow discourses of skin-color-based identity (Figure 29). Grove used this cover imagery to imply that, for white readers, the book would expose the psychological mechanisms hidden behind the white mask. Indeed, the ad for Black Skin, White Masks on the back cover of the June 1967 Evergreen Review features a photograph of Fanon himself with a white mask, underneath which are the questions: “Why the white mask? What is he hiding? What does he fear?” The copy underneath then promises that “BLACK SKIN, WHITE MASKS by Frantz Fanon, available at last in English, gives the answers.” However, this ad, as well as the back cover of the book itself, features a quote from Floyd McKissick, former national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, asserting, “This book should be read by every black man with a desire to understand himself and the forces that conspire against him.” Even though the primary audience for Grove’s books in the late 1960s was the predominantly white counterculture, Rosset and his colleagues were nevertheless aware of a growing African American market for revolutionary literature, and they strove to address this audience as well.

Figure 28. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Black Cat edition of

The Wretched of the Earth (1968).

Figure 29. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Black Cat edition of

Black Skin, White Masks (1968).

In this effort, Grove was part of a growing mainstream awareness of and interest in the relationship between reading and racial demographics that accompanied the rise of the Black Power movement. In April 1967, the New York Times article “What the Negro Reads” reported on a survey of the reading preferences of African Americans. It concluded that they were reading “books on civil rights, the Negro’s place in history, works on the Muslim and Nationalist movements and, being practical, self-help books.”13 Two years later the Times featured an article more pointedly entitled “Black Is Marketable,” asserting that “last year the greatest paperback sales upsurge in any given cultural category occurred with those books dealing with aspects of Afro-American experience.” To support this claim, the article cites Morrie Goldfischer, Grove’s director of publicity, avowing that “only those books with revolutionary themes have shown comparative increases.”14 Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Grove endeavored to exploit this heightened interest, publishing, in addition to Fanon, Herbert Aptheker’s Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion; Turner Brown Jr.’s Black Is; Aimé Césaire’s A Season in the Congo; Paul Carter Harrison’s The Drama of Nommo and Kuntu Drama; plays, poetry, and fiction by LeRoi Jones/ Amiri Baraka; and a variety of other titles promoted in full-page ads as “the black experience in Grove Press paperbacks.”

Grove’s most successful and significant title in this category was The Auto-biography of Malcolm X, which Doubleday was originally to have published. The book was already in galleys when he was assassinated, but the subsequent threats and violence gave Doubleday cold feet. Rosset was quick to step in, issuing the hardcover in an initial printing of ten thousand copies in the fall of 1965 and the Black Cat paperback in the fall of 1966. Grove put its full promotional efforts behind the book, which was widely reviewed, discussed, advertised, and read over the course of the late 1960s, despite Malcolm X’s overwhelmingly negative image in the mainstream white press. Truman Nelson, writing for the Nation, hailed it as “a great book”; and Eliot Fremont-Smith, writing for the New York Times, called it “a brilliant, painful, important book.” Both these phrases were prominently featured in Grove’s advertisements, many of which were full page, in both the black and the white press, as well as on the book’s back cover. Harry Braverman, along with Jules Geller and Grove’s house counsel Dick Gallen, was instrumental in both the design and the aggressive marketing of this profoundly significant Sixties text.

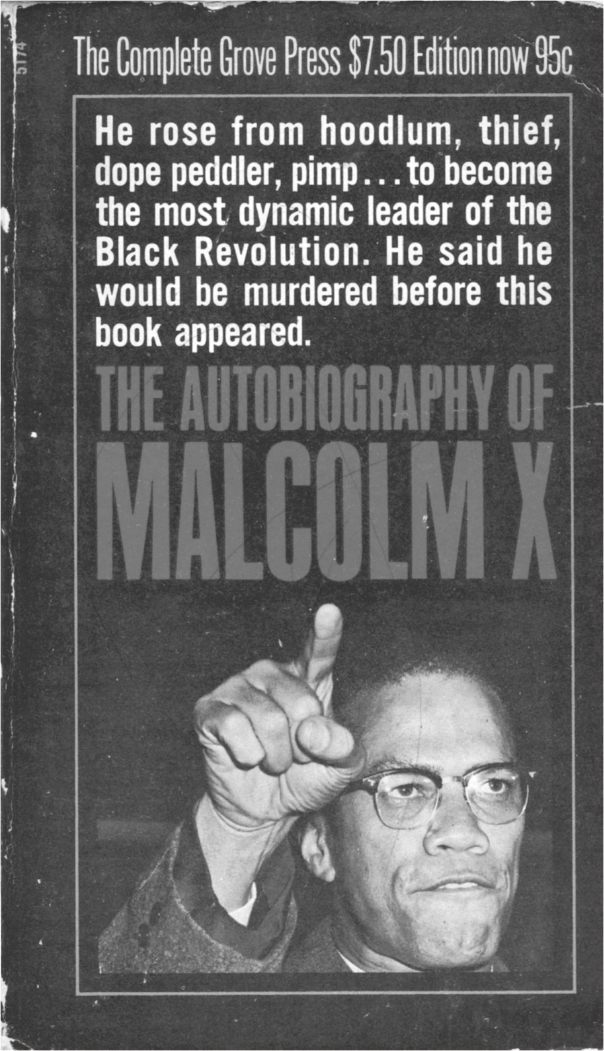

In the 1993 article “Merchandising Malcolm X,” Gail Baker Woods claims that “after his death, the media basically ignored Malcolm X,” but Grove’s campaign, and the remarkable success of the book itself, contradicts her.15 According to Grove’s sales records, the paperback had gone into a ninth printing for a total of 775,000 copies by August 1968. By 1970, Grove had sold more than one million copies, making Malcolm X’s image and story familiar to millions of Americans, both white and black. It was an image and a story of revolutionary conversion, as the tagline that runs across the front cover, in white type against a black background, confirms: “He rose from hoodlum, thief, dope peddler, pimp . . . to become the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. He said he would be murdered before this book appeared.” Below these lines, which were used in all advertising for the book, the title appears in red. The bottom third of the cover features the now-iconic UPI photograph of Malcolm X, his lower lip held tensely beneath his teeth, his forefinger pointing forward and up. The gesture’s authoritative power is enhanced by the photo’s position at the bottom of the cover, which makes it look as though he is pointing to the title, as well as the prophecy above it (Figure 30). In the same year, Grove brought out the Evergreen paperback edition of Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism, and the two authors appeared alongside each other in much of Grove’s promotion of the newly renamed genre of black writing in the late 1960s.

The Black Cat edition’s back cover features a single quotation from the final chapter, in yellow type, which predicts, “I do not expect to live long enough to read my book.” The poignancy of this prophecy is deepened by the fact that reading is so central to the autobiography itself, as Malcolm X famously begins his conversion in the Norfolk Prison Colony’s library, and he remained a voracious and omnivorous reader over the rest of his short and highly eventful life. As reviewers and critics have noted ever since, this conversion through literacy placed the autobiography in a tradition of African American writing running back to the slave narratives of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (as well as in a longer tradition of religious-conversion narratives running back through Saint Augustine), while its heavy emphasis on education and discipline placed its subject in the lineage of American self-made men epitomized by Ben Franklin. Thus, Grove could promote Malcolm X both as a radical revolutionary and as a more conventional proponent of self-reliance. His image fused the opposed strands of African American leadership most starkly represented in an earlier generation by W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington; thus, his autobiography could be marketed both as a revolutionary handbook and a self-help guide.

Figure 30. Cover of Black Cat edition of The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1966). (Photograph by UPI)

The promotional power of this image is illustrated by the Los Angeles Public Library’s pamphlet “The Bibliography of Malcolm X,” a list of books Malcolm X read in prison.16 The pamphlet sports the same photo as the Grove edition, over which is the quote, “I have often reflected upon the new vistas that reading opened to me. I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life.” Inside is a selection of the titles he read in prison, including a dictionary, Will Durant’s Story of Civilization, H. G. Wells’s Outline of History, W. E. B. Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Gregor Mendel’s Findings in Genetics, the Bible, Shakespeare, and Paradise Lost. It then emphasizes that “anyone who lives, works, or goes to school in Los Angeles has free access to library materials . . . some of which might change and improve your life. Let the power of books work for you!” The library’s reliance on the Grove design for its “bibliography” confirms the degree to which Grove’s marketing succeeded in representing Malcolm X’s autobiography as a testimony to the power of the printed word.

During his lifetime, Malcolm X had been an enormously popular speaker on college campuses, and his autobiography’s emphasis on education and self-determination enhanced its popularity in universities, colleges, and high schools across the country. Its educational sales were further boosted when it was adopted by the Scholastic Book Club. To capitalize on and enhance this popularity, Grove’s education department, which under Jules Geller had recently established a separate black studies program, issued a discussion guide for the text “as an aid to a meaningful exploration of the reality of life in America.”17 Mirroring the combination of revolutionary philosophy and pragmatic self-discipline promulgated by the text itself, the guide ranges from questions about vocabulary and plot to far more radical challenges such as whether ghettoes can be eliminated “by legislation and/or revolution,” or whether African Americans should appeal to the United Nations in order to “internationalize the struggle.” The guide also includes a list of courses in which the book has been adopted, ranging from high school English and social studies to college courses in history, sociology, philosophy, American studies, and even business administration. It concludes with a list of recommended reading, including Grove Press titles Malcolm X Speaks, Black Skin, White Masks, Wretched of the Earth, and Look Out Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama! Brought out in the watershed year of 1968, when The Autobiography of Malcolm X was its most widely adopted book for course use, Grove’s study guide confirms the degree to which it was in the vanguard of the curricular revisions that transformed American education in the coming decades.

Not only did Grove publish and promote many texts that were instrumental in the transition from civil rights to Black Power but it also tracked and encouraged this transition in the pages of the Evergreen Review, which became increasingly associated with the New Left and the radicalization of the Movement over the course of the late 1960s. Initially, the principal writer responsible for reporting on African American issues (and Movement politics more generally) was the prolific journalist Nat Hentoff, a regular contributor to the magazine. In November 1965, in his article “Uninventing the Negro,” Hentoff reported on the three-day conference “The Negro Writer’s Vision of America,” held at the New School and cosponsored by the Harlem Writer’s Guild, which featured James Baldwin as keynote speaker, along with panelists LeRoi Jones, Sterling Brown, Abbey Lincoln, and others. According to Hentoff, “The main, if tangled, theme of the conference [was] the need to discard the very word, ‘Negro.’”18 He organizes his article around the recurring discussion of the term, including an endorsement of its abandonment by Richard Moore of the Frederick Douglass Book Center and a summation speech by John Killens concluding that “Afro-American is a more exact and scientific description of the black American.”19

In the following year, Hentoff contributed “A Speculative Essay,” more practically entitled “Applying Black Power.” Noting the need for the nascent Black Power movement to shift “from rhetoric to programmatic action,” Hentoff details a variety of community programs, from neighborhood patrols to black para-unions to economic boycotts, which could effect this translation.20 He particularly emphasizes the importance of “black students and intellectuals,” reporting favorably on the formation in New York of the Afro-American Students for Community Improvement and Development. He concludes optimistically that, with effective organization, “men like Stokely Carmichael and Floyd McKissick have an opportunity to make black power so meaningful that the main question asked a decade or two from now will be why it took so long in coming.”21 Together, Hentoff’s articles effectively illustrate the linked objectives of the revolutionary handbooks Grove published in the 1960s: the radical transformation of consciousness and the practical attainment of political power.

Not until 1969 did the Evergreen Review hire an African American as contributing editor, and for the next few years civil rights veteran Julius Lester was a regular contributor to the magazine during its final turbulent period, providing additional credibility to its reporting on African American issues. Lester was aware of the aura of tokenism that would accompany his association with a magazine owned and run by whites, and he addressed the issue in a 1970 article, “The Black Writer and the New Censorship.” Opening with the sentence, “In the latter half of the sixties more books by black writers were published than in any other decade of American history, which isn’t saying much,” Lester affirms the degree to which the explosion of interest in books by and about African Americans was being managed and mediated by an industry dominated by whites whose identity and experience rendered them incapable of fully understanding or evaluating the literature they were publishing.22 Without naming names, Lester proclaims that “white editors are not equipped, by education or psychology, to evaluate a manuscript by a black writer.” Nevertheless, he also concedes Grove’s vanguard efforts in this emergent market, noting that “the publication of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and The Autobiography of Malcolm X preceded the black power explosion and . . . ran interference for the books which were to come.”23

Though most of the books Lester mentions were handled by white editors and publishers, many of them were sold in black-owned bookstores that, according to an August 20, 1969, article in the New York Times, were springing up all over the country in the late 1960s. Frequently modeled on Harlem’s legendary National Memorial African Bookstore, where Malcolm X himself used to spend time, these stores, owned and operated by African Americans and located in African American communities, were the principal outlet in those communities for the titles discussed here. Thus, even if the publishing industry in the 1960s remained dominated by whites, the retail and reception end of the communications circuit for black writing was becoming more autonomous. Such bookstores stocked a wide variety of titles issued by both black and white publishers, but the article notes that “if one book stands out, it is ‘The Auto-biography of Malcolm X.’ Every shop ranks it a best seller.”24 Other popular titles included Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land, Harold Cruse’s Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, H. Rap Brown’s Die, Nigger Die, and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.

Lester’s contribution to this emergent canon was the wonderfully titled Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama!, issued as a Black Cat paperback in 1969. The front cover illustrates Kuhlman’s creative use of typography in his design of Grove’s revolutionary texts. Clearly derived from the layout of the hardcover dust jackets for Fanon, the cover of Look Out, Whitey! features simply title and author in crude block caps against a white background, with “Look Out, Whitey” and Lester’s name in black, “Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama” in gray, and both exclamation points in red. As on the cover of Black Skin, White Masks, the color scheme comments on the racially divided audience addressed by the text, with “Whitey” in black and “Black Power” in gray, simultaneously affirming and complicating the dualistic presumptions of “white” and “black” identity (Figure 31).

The back cover elaborates on the rhetorical complexities of this design, with promotional commentary by white writers in black type divided by red ruled lines with the writers’ names in gray: Truman Nelson, reviewing the book for the New York Times, calls it “a magnificent example of the new black revolutionary writing”; Hentoff, reviewing it for the Nation, calls it “a book that ought to be the basis for a whole year’s work in every high school in the country”; and Publishers Weekly recommends it as “part of the survival kit America needs to remain a viable society.” In typographically playing on the rhetoric of racial identity, and in categorizing the text itself as a pedagogically structured “survival kit,” these paratexts illustrate the degree to which Grove’s publication of Fanon laid the groundwork for the marketing of Lester’s text, which subsequently appeared alongside those of Fanon, Malcolm X, LeRoi Jones, and others in Grove’s promotion of black writing. It eventually sold more than one hundred thousand copies.

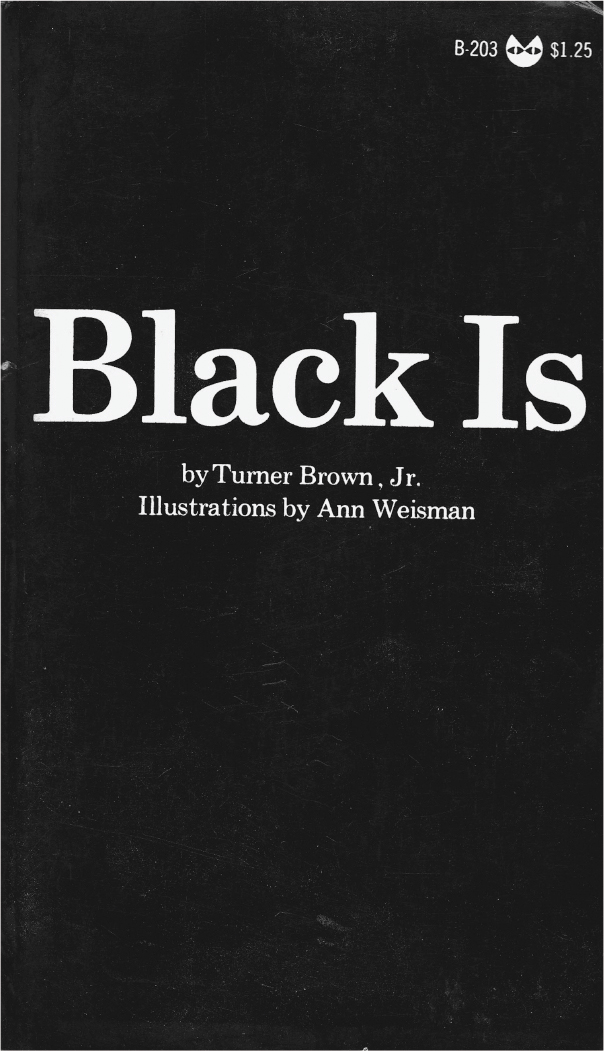

A title that even more explicitly illustrates how Grove’s intervention in the 1960s discourse of racial identity relied on typographical tropes is Turner Brown Jr.’s Black Is, with illustrations by Ann Weisman. By inverting the nighuniversal convention of black type on a white page, Black Is foregrounds the degree to which the opposition of black and white is implicated in the very materiality of the printed book. The cover of the Black Cat edition is, appropriately, black, with both title and colophon in white. Inside, all recto pages are black, with Brown’s provocative epigrams on race relations in white type, and all verso pages are white, with Weisman’s illustrations in black ink. The first two pages oppose the publication information in black type against a white page with Webster’s definition of the word black in white type against a black page. The definition is reproduced in full typographic detail, such that the word black appears in italics in all of the examples of usage. As both material object and text, Black Is illustrates the complex ways in which the design of the paperback book could, in and of itself, be part of the larger dialogue about racial identity (Figure 32).

Figure 31. Roy Kuhlman’s cover for the Black Cat edition of Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama! (1969).

Figure 32. Cover for Black Cat edition of Black Is (1969).

Look Out, Whitey! is, by contrast, a relatively straightforward account of the historical antecedents to and causes of the transition from civil rights to Black Power in the 1960s, the central objective of which is to justify and explain its title’s rhetorical structure. Thus, in the opening chapter Lester affirms, “No more did you hear black people talk about ‘the white man’ or ‘Mr. Charlie.’ It went from ‘white man’ to ‘whitey’; from ‘Mr. Charlie’ to ‘Chuck.’ From there he was depersonalized and called ‘the man,’ until in 1967 he would be totally destroyed by one violent word, ‘honky’!”25 Later on, citing Ossie Davis’s seminal Ebony eulogy for Malcolm X, which had achieved particularly wide circulation as an appendix to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Lester affirms, “Blacks now realize that ‘Negro’ is an American invention which shut them off from those of the same color in Africa.”26 Lester predictably concludes by affirming the international alliances enabled by the terminological and political shift from civil rights to Black Power, noting that “Black Power is not an isolated phenomenon. It is only another manifestation of what is transpiring in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.”27 Citing Fanon as his authority, Lester prophesies that “the concept of the black man as a nation, which is only being talked about now, will become reality when violence comes.”28 The rhetoric of the title, then, is simply prelude to the revolution it presages.

The short-lived hope that this revolution might in fact happen was buttressed by the one that had already successfully occurred some one hundred miles off the coast of the United States only a decade earlier. Far more than the Algerian War, whose events and participants, Fanon notwithstanding, would have seemed relatively distant to many Americans, the Cuban revolution and its charismatic leaders inspired radical activists in the United States throughout the 1960s. Grove Press, in frequent collaboration with Monthly Review, became a central conduit for the dissemination of their words and images in the turbulent second half of that decade (as Rosset quips in an unpublished interview, “I loved the idea of Cuba. It was sex and politics, really connected!”).29 Visits to Cuba, forbidden by the State Department but frequently possible by way of Mexico or Spain, became de rigueur for committed activists and artists during the 1960s (including Richard Seaver and Barney Rosset, who, both left-handed, had to work a separate plot in the fields so as not to injure anyone with their machetes). Evergreen Review frequently published their accounts, starting with LeRoi Jones’s “Cuba Libre” in the November–December 1960 issue, which also featured a “Declaration concerning the Right of Insubordination in the Algerian War,” signed by a group of French intellectuals including Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Claude Simon. In late 1967, poet and photographer Margaret Randall reported on her “impressions, often at random” of her visit to Cuba to attend the “Encuentro con Rubén Darío” along with “some eighty other poets/critics/intellectuals from all over the world” for the Evergreen Review’s new section “Notes from the Underground.” One of Randall’s more noteworthy impressions is of “a bookstore, enormous, called La Moderna Poesia” where she sees “books from all over the world, in quantity and quality to fill the demands of seven million people who know how to read and want to.”30 As Randall’s report affirms, a central component of Cuba’s revolutionary image involved both the democratization of literacy and the radicalization of the literary. Cuba modeled the conviction that reading and revolution are co-implicated.

After the revolution itself, the central event in the idealization of the Cuban model was the death of Che Guevara in Bolivia in 1967, which sparked an extensive publishing campaign instrumental both in galvanizing Che’s image as a romantic revolutionary and in affirming Grove’s position as one of its key promulgators. As Michael Casey affirms in Che’s Afterlife, the cover of the February 1968 Evergreen Review, which featured a painting by Paul Davis based on Korda’s photograph, provided the now-famous image of Che with “its first widespread appearance in the United States.”31 Grove promoted the issue heavily, distributing posters throughout New York City and the rest of the country, announcing that “the Spirit of Che lives in the new Evergreen” (Figure 33).

This issue of Evergreen Review features Fidel Castro’s eulogy for his fallen comrade, a reprint of journalist Michel Bosquet’s report on Che’s “last hours” for Le nouvel observateur, one of the opening chapters of Che’s Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War (published in hardcover by Monthly Review and then distributed as a Black Cat paperback by Grove), Che’s 1965 farewell letter to Castro (also included in Reminiscences), a “message” from Régis Debray along with an account of his arrest in Bolivia, and a reprint of K. S. Karol’s interview with Fidel, also from Le nouvel observateur. The articles are set off as a separate section introduced by a bright red title page featuring a reproduction of Korda’s photo above the phrase “The Spirit of Che.” Below this title appears a quotation from Bosquet’s article reinforcing the self-consciously Christian iconography of the portrait:

If the Latin-American colonels and their Yankee advisers believe today, as Time magazine wrote a few weeks ago, that Che’s disappearance deprives subversion of much of its mystery and romanticism, they are doubtless committing the same error the Romans committed nineteen hundred and thirty years ago when they executed, together with two thieves, a Jewish agitator whose ideas eventually triumphed over the greatest empire in the history of the world.32

Figure 33. Illustration of Che Guevara for the cover of Evergreen Review (February 1968). (Illustration by Paul Davis)

Prominently featuring the famous photo of Che’s corpse surrounded by Bolivian military officials, this combination of eulogy, farewell, and reminiscence positions Che’s martyrdom in explicit contrast to the dismissive reports promulgated by Time, here directly identified as the mouthpiece of the neocolonial forces responsible for his death. And the concluding lines of Fidel’s eulogy, “El Che vive!,” further affirm that “it will not be long before it will be proved that his death will, in the long run, be like a seed which will give rise to many men determined to imitate him, men determined to follow his example.”33 Grove hoped to fertilize the soil in which this seed could grow.

Toward this end, Grove published a Black Cat mass-market reprint of the Monthly Review’s translation of Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, Che’s eyewitness account of the Cuban campaign from the landing of the Granma to the decisive battle of Santa Clara; and also in coordination with the Monthly Review, a Black Cat edition of his speeches, Che Guevara Speaks, edited by George Lavan and featuring the Davis portrait on the cover. Buttressing the rhetoric of redemption that was enhanced by his martyrdom, the concluding lines of Reminiscences affirm, “We are now in a situation in which we are much more than simple instruments of one nation; we constitute at this moment the hope of unredeemed America.”34 And the preface to Che Guevara Speaks announces that “the vanguard youth are . . . taking Che as their own: he will live for a long time to come in helping to shape the aspirations and goals of the new generation on whom the hope of the world rests.”35 Comparable to the paired marketing of The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Malcolm X Speaks, these books together promised to provide readers with both empirical evidence of and practical guidelines for the development of revolutionary consciousness. As Julius Lester affirmed in his October 16, 1967, editorial for the New York Westside News, reprinted the following year in the Black Cat edition of his Revolutionary Notes (billed on the back cover as “a book to carry to the barricades”), “Che Is Alive—on East 103rd Street.”36

Che had kept a journal during the failed Bolivian campaign, and after his death rumors circulated widely that it was in the possession of the Bolivian military, sparking what Publishers Weekly called “The Che Guevara Sweepstakes,” in which a variety of publishers, both mainstream and underground, scrambled to get their hands on all, or at least some, of what was briefly one of the hot literary properties of 1968.37 As Fred Jordan recounted to me, “Everybody wanted to find the diaries, everybody. We wanted it, too.” Working on a tip he received from connections he had at the Cuban mission to the United Nations, Rosset sent writer Joe Liss to Bolivia with eighty-five hundred dollars in small bills to see if he could acquire the sought-after journals. Liss was instructed to pose as a screenwriter (which he was) collecting material for a film on Che Guevara (which he wasn’t). The screenwriting ruse was also the basis for the code Rosset and Liss established in order for Liss to report his progress without attracting suspicion. After a series of contretemps, Liss was able to hook up with Gustavo Sánchez Salazar and Luis Gonzales Sr., Bolivian journalists working on a book about Che’s campaign, who initially suspected him a being a CIA agent. Liss was able to convince them otherwise, and they provided him with photographs of Che in Bolivia along with photostats of a small portion of the diary (which had, in fact, been scattered across Bolivia by various interested parties, making it impossible to obtain the entire document). Liss called Rosset, but they were unable to communicate effectively in the code they had established, so Jordan and Rosset flew to Bolivia to see for themselves. As Jordan further recounts, “We arrive in La Paz, and Barney disappears . . . I was furious.” Eventually, Rosset and Jordan managed to negotiate for the photos and a larger portion of the journal and offered Salazar and Gonzalez an advance of twenty-seven thousand dollars on their book, which Grove published in translation the following year as The Great Rebel: Che Guevara in Bolivia.38

The risks involved in such a venture were confirmed on the night of July 26, 1968, when a fragmentation grenade was tossed through the window of Grove’s University Place offices. Credit for the bombing was claimed by the Movimiento nacional de coalición cubano, which had timed the attack to coincide with the fifteenth anniversary of Fidel’s famous raid on Batista’s army in Santiago, but Rosset was convinced, although he was never able to prove, that the CIA was also involved. Grove continued to receive bomb threats in the ensuing months, and for a time fire engines mysteriously blared their sirens outside the offices on an almost daily basis, but Rosset, undeterred, published the excerpts in the August 1967 Evergreen Review. They were heavily illustrated, including a gruesome full-page photograph of Che’s corpse, the tagline for which notes that “this and similar photographs are widely in demand by the Indian farmers of the area where Che was killed, to be framed and hung like ikons [sic] next to pictures of Christ.”39 The excerpts are supplemented by a twopage guide, “Who’s Who in Che’s Diary,” providing names of the Cuban agents who accompanied him (which had been withheld from the official version of the journal issued by Cuba’s Instituto nacional del libro), and illustrated with drawings by Carlos Bustos, the Argentinian artist arrested with Régis Debray.

Debray is an important figure in the network that produced and distributed the literature of revolution in the 1960s. His book, Revolution in the Revolution?, issued in hardcover by Monthly Review and as a Black Cat paperback in 1967, is an exemplary version of the so-called revolutionary handbook, and his itinerary illustrates some of the geopolitical realignments that occurred in that network over the course of the 1960s. Starting out as a student of philosophy at the École normale supérieure under Louis Althusser, Debray first visited Cuba in 1961, where he met with both Che and Castro; he traveled throughout Latin America in the early 1960s, after which he returned to France, where he wrote a number of influential articles in both French and Spanish on Cuban revolutionary strategy and the “Latin American way.” In 1965, he returned to Cuba as a professor of philosophy at the University of Havana. In 1967, he went to Bolivia to join Che’s campaign, where he was arrested shortly before Guevara himself was captured and killed. The Bolivian government sentenced Debray to thirty years in prison, and he became a cause célèbre around the world until his release in 1970.

Although Debray was arrested for aiding the insurgency, Grove claimed that his real crime was writing Revolution in the Revolution?, whose front cover bills it, citing Newsweek, as “a primer for Marxist insurrection in Latin America.” The back cover specifies, in bold red type, “For having written this book, twenty-six-year-old Régis Debray is under arrest in Bolivia awaiting trial and a sentence that could be death before the firing squad.” The front matter on the opening page elaborates that “whatever the Bolivian authorities may charge, Régis Debray’s real crime is having written this book.” The foreword goes on to quote none other than Jean-Paul Sartre (who had himself visited Cuba in 1960 and famously called Che “the most complete human being of our age”) as affirming that “Régis Debray has been arrested by the Bolivian authorities, not for having participated in guerilla activities but for having written a book—Révolution dans la révolution?—which ‘removes all the brakes from guerrilla activity.’”40 Grove billed Revolution in the Revolution? as the ultimate crime of writing, a book that posed a threat not only to the First World powers striving to perpetuate neocolonial influence in Latin America but also to their Soviet and Chinese adversaries.

Revolution in the Revolution? partakes of the postwar realignment of anti-colonial struggle from an east-west to a north-south hemispheric axis, foregrounding the very term “America” as subject and substance of revolutionary transformation. The book was originally written in Spanish and published in Havana, with an introduction by the Cuban author Roberto Fernández Retamar, as the inaugural volume in the Cuadernos series of the Casa de las Americas and with the explicit purpose of providing guidance for revolutionaries throughout Latin America. In their foreword, Monthly Review editors Leo Huberman and Paul Sweezy affirm that “Debray, though writing only in his capacity as a private student of revolutionary theory and practice, has succeeded in presenting to the world an accurate and profound account of the thinking of the leaders of the Cuban Revolution.” And they insist that, though the book was written with a Latin American audience in mind, it “represents a very real challenge to all revolutionaries everywhere.”41

Revolution in the Revolution? was widely reviewed, and the framework within which the mainstream press presented it reveals that the idea of a “handbook” for revolution had become an established generic category. The New York Times reviewed it as a “Guerilla Blueprint”; the Nation as a “Primer for Revolutionary Guerillas”; and, as we have seen, Newsweek called it “a primer for Marxist insurrection in Latin America.” It ended up selling more than seventy thousand copies.

Even though Debray’s ideas were met with varying degrees of skepticism, all reviewers agreed that the central conceptual and practical component of the book is the military “foco,” the small group of guerrillas who in their very composition make up the seedbed of the revolution. The inaugural model of this utopian group formation is, of course, the eighty-two members of the 26th of July Movement who joined Fidel Castro and Che Guevara on the Granma for its famous voyage from Veracruz to Cuba, and the purpose of Debray’s book is to prove that this model is appropriate to all Latin American countries under dictatorship. But the “foco,” as Fredric Jameson has argued in “Periodizing the Sixties,” is more than just a descriptive term; it is “in and of itself a figure for the transformed, revolutionary society to come,” and, I would argue, it was in these utopian extensions that it would be so compelling to American readers during that brief interregnum in the late 1960s when world revolution, to both its adherents and its enemies, seemed historically possible.42 While the empirical referent of the “foco” was geographically specific, its potential for replication and extension was vast and enabled any small group with enough radical fervor to consider itself in the vanguard of the revolution. As Debray himself confirms toward the end of his short book, “Fidel Castro says simply that there is no revolution without a vanguard; that this vanguard is not necessarily the Marxist-Leninist party; and that those who want to make the revolution have the right and the duty to constitute themselves a vanguard, independently of those parties.”43 Revolution in the Revolution? provided both ideological license and practical guidance for such self-constitution.

In a sense, Grove Press in the late 1960s was both experienced and perceived by members of the counterculture as something of a “foco,” a small group of leftists committed to both modeling and fomenting a revolution. Not only did Grove have a revolutionary reputation that increasingly drew radical writers and readers into its orbit but its offices were a social nexus for Movement intellectuals, and every year idealistic young people migrated to New York City in the hopes of being able to work for Grove.

The author who most effectively modeled the radical possibilities of Grove’s volatile nexus of aesthetic and political avant-garde sensibilities in the 1960s was Jean Genet, who became increasingly involved in revolutionary politics in the second half of the decade. Genet had, for all intents and purposes, stopped writing in 1961, and after the controversial 1966 Parisian production of his last play, The Screens, based on the Algerian War, he fell into a deep depression that lasted until the galvanizing events of 1968. After witnessing the suppression of the Paris uprising in May, Genet, partly funded by Grove, sneaked into the United States through Canada to attend the Democratic Convention in Chicago and report on it for Esquire, along with William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Terry Southern. Genet had agreed to write the article on the condition that Esquire also accept a second one condemning the Vietnam War. In the end, Esquire took the report on the convention but rejected the article on Vietnam, which was translated by Richard Seaver (who had accompanied Genet to Chicago) and published as “A Salute to 100,000 Stars” in the December 1968 issue of Evergreen Review.

Genet’s “Salute” is structured as a poetic/erotic wake-up call to Americans mourning the soldiers killed in Vietnam. Opening with the question, “Americans, are you asleep?,” Genet proceeds to evoke such a soldier’s death—“brain exploded, members scattered, penis stupidly ripped off, butts in the sun”—contrasted with the family that “will hang a small star in the window of its house” in memoriam.44 Contending that “your dead child is a pretense to decorate your house,” Genet goes on to affirm that the causes of America’s intervention in Vietnam are simultaneously political and aesthetic. Thus, he includes such parenthetical notes as “I think you are losing the war because you are ignorant of elegant syntax” and “You are losing this war because you do not listen to the singing of the hippies,” and he concludes by encouraging Americans to remember “this line of Rilke: ‘You must create chaos within yourselves so that new stars will be born.’”45 Genet’s “Salute” illustrates the persistence of modernist aesthetics in the political rhetoric of the counterculture. Even though both Sartre and Genet had condemned and abandoned “literature” as irredeemably bourgeois in the late 1960s, their political authority was still based in the cultural capital accruing to their literary reputations. Genet illustrates this persistence in his very person, as a “star” whose dissident charisma, based in the books and plays that were now popularly available throughout the country and the world, could enhance the visibility of groups participating in revolutionary struggle.

A few months later, Evergreen published an article that can be understood as a response to Genet’s call for chaos: Jerry Rubin’s “A Yippie Manifesto.” Featuring a full-page photo of its author dressed as a Viet Cong soldier for his appearance at the House Un-American Activities Committee hearing to which he had been summoned, Rubin’s famous manifesto affirms that “revolution only comes through personal transformation.”46 Invoking the spirit if not the letter of Debray’s theory of the “foco,” Rubin announces that “within our community we have the seeds of a new society. We have our own communications network, the underground press. We have the beginnings of a new family structure in communes. We have our own stimulants.”47 The Yippies’ unique combination of absurdist humor and activist brio fused the political and aesthetic meanings of the avant-garde, and Grove was a central node in the communications network that distributed their irreverent calls to transformative action. In addition to featuring Rubin’s manifesto in Evergreen, Grove published Ed Sanders’s Yippie novel Shards of God (1970), distributed Abbie Hoffman’s celebrated Steal This Book (1971), and issued a set of satirical handbooks on avoiding work, making love, and beating the draft by Tuli Kupferberg.

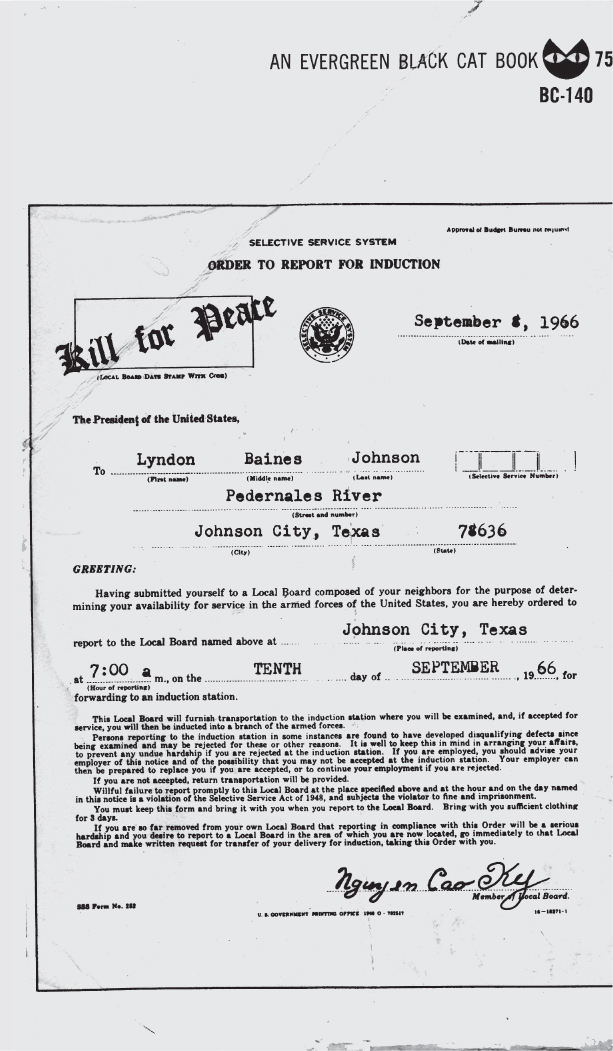

Originally published as a stapled pamphlet by Oliver Layton Press in 1966 and then as a Black Cat paperback in 1967, 1001 Ways to Beat the Draft, assembled by Kupferberg and Robert Bashlow, is a list of satirical suggestions for draft evasion (number 1 is “Grope J. Edgar Hoover in the silent halls of congress”; number 2 is “Get thee to a nunnery”).48 The list is interspersed with newspaper clippings, photos, cartoons, and other printed matter, both contemporary and historical, meant to communicate the absurdity and brutality of war in general, and of the Vietnam War in particular. The front cover features a World War I–era illustration of a soldier with his head being blown off by his own rifle; the back cover features a reproduction of an induction order addressed to Lyndon Johnson and signed by Nguyen Cao Ky (Figures 34 and 35). As a countercultural collage, 1001 Ways to Beat the Draft, along with its companion volumes 1001 Ways to Make Love (1969) and 1001 Ways to Live without Working (1967), uses a combination of aesthetic and political tactics in an attempt to revolutionize the very structure and purpose of the paperback book.

In 1971, Grove agreed to distribute Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book, a “handbook of survival and warfare for the citizens of Woodstock nation” that, according to Hoffman, had been rejected by more than thirty publishers, including Random House, Macmillan, McGraw-Hill, Harper and Row, and Ballantine. Organized into three sections—“Survive!,” “Fight!,” and “Liberate!”—Steal This Book is a surprisingly practical guide to revolutionary action, providing precise instructions for obtaining free food, clothing, and housing; setting up guerrilla broadcasting networks and organizing demonstrations; and getting first aid and legal advice, among other things. Extensively illustrated with photos of activists, panels from underground comics, and images culled from old newspapers and magazines, Steal This Book enacts the do-ityourself aesthetic that it encourages its readers to replicate across the country. In its explicit address to a revolutionary subculture, it embodies the logic of the “foco” that had provided the political justification for Grove’s investment in this Sixties genre.

Figure 34. Front cover of the Black Cat edition of

1001 Ways to Beat the Draft (1967).

Figure 35. Back cover of the Black Cat edition of

1001 Ways to Beat the Draft (1967).

Figure 36. Cover for Black Cat edition of The New Left Reader (1969).

Hoffman wrote the introduction to Steal This Book in jail, which he calls a “graduate school of survival.”49 It is something of an irony of history that Grove’s canon of texts, including its revolutionary handbooks, ended up on the curriculum of graduate schools across the nation. In 1969, Grove issued a Black Cat paperback that anticipates this development. The New Left Reader, edited by former SDS president and Movement “heavy” Carl Oglesby, features a marquee list of radical intellectuals, including C. Wright Mills, Herbert Marcuse, Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Fidel Castro, and Leslie Kolakowski, almost all of whom had been published by Grove in one form or another over the past decade. With the title in white, selected contributors’ names in orange, and editor’s name in red, against a black background within a red frame, the design of The New Left Reader uneasily integrates the various typographical tropes illustrated by Grove’s revolutionary handbooks (Figure 36). Yet it is highly significant that this book, billed on the back cover as “for anyone who wishes to understand the complex thought behind the actions that are affecting the entire world,” is called a “reader” and not a “handbook,” and that, in offering the “philosophical and political roots” of the New Left, it also anticipates the turn to theory and the retreat into the university that quickly ensued.

Oglesby’s organization of the anthology reflects its transitional position. Part 1, “Understanding Leviathan,” includes pieces by C. Wright Mills, Herbert Marcuse, and Louis Althusser, along with excerpts from Stuart Hall, Raymond Williams, and E. P. Thompson’s May Day Manifesto of 1967. Part 2, “The Revolutionary Frontier,” features work by Frantz Fanon, Fidel Castro, Malcolm X, and Huey Newton. Part 3, “A New Revolution?,” features essays by student leaders Rudi Dutschke, Daniel and Gabriel Cohn-Bendit, Tom Fawthrop, Tom Nairn, David Treisman, and Mark Rudd, all commenting on the events of 1968, in whose immediate aftermath this anthology was assembled.

The year 1968 is, of course, a watershed in all histories of the 1960s, and it is notable that most of the figures from parts 1 and 2 of Oglesby’s reader have since become canonical, but the new student leaders who contributed the materials for part 3 have, for the most part, vanished into history, providing a negative answer to the question asked by Ogleby’s section title. But if Oglesby’s desire to situate these student activists in the political vanguard remained unrealized, his knowledge that they represent a “new class,” a class for whom figures like Althusser and Fanon are foundational, has come to fruition.50 What The New Left Reader reveals in retrospect is the cultural significance of Grove’s catalog for this new class. Once the possibilities of political action promised by its revolutionary handbooks were foreclosed, the political theories that informed them became required reading.