CHAPTER 1

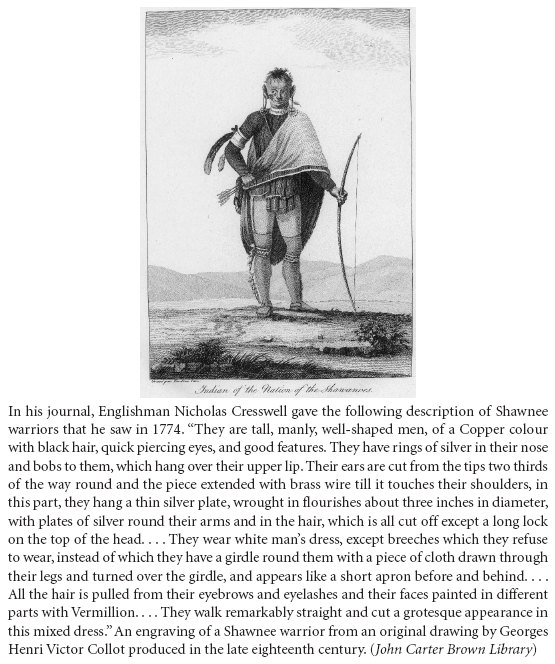

Our Customs Differing from Yours

Cultural Friction and Conflict on the Frontier

October 1773–March 1774

IT IS 1773 VIRGINIA.1 Early in the morning on Sunday, October 10, eight men—six whites and two black slaves—lie sleeping in their camp on the west bank of Wallen’s Creek in Powell’s Valley on the Virginia frontier. Before bedding down the previous night, they had unburdened their pack horses so that bundles of supplies, including sacks of flour and other provisions, were lying about them. Their cattle and tethered horses slept or grazed nearby. The men would soon have to rise, gather the livestock, load the pack animals, and resume the march. They needed to go only a few more miles along this branch of an Indian trail known as the Warriors’ Path to rejoin their group’s main body.2 History would soon count members of the caravan among the first victims claimed in a clash of cultures that became the last conflict of America’s colonial era. Within months of its conclusion, the first shots of independence at Lexington and Concord would be fired.

As dawn approached, the horses suddenly became restless and agitated. A party of nineteen Indian warriors had observed and shadowed the group ever since it entered the valley. Returning from a congress of several nations’ representatives to discuss how to contend with continued white expansion into the hunting ground on the south bank of the Ohio River, the band presumably included fifteen Delaware, two Cherokee, and two Shawnee warriors. No official state of war existed between the British and the several nations whose hunters they might have encountered in these woods. If the members of the caravan had even seen the Indians, they would certainly not have assumed they were hostile, and therefore took no extraordinary security precautions. The braves moved silently forward as they would on a hunt when approaching unsuspecting deer until each came to a position that offered an unobstructed view of their quarry. The warriors raised their muskets, cocked their firelocks, and took aim at the figures huddled near a campfire against the coolness of the early autumn morning.3

At daybreak, musket fire and blood-curdling war whoops pierced the stillness as the Indians rushed in and overran the camp. The warriors who killed brothers John and Richard Mendenhall with the opening fusillade immediately pounced on and scalped their lifeless corpses. The braves who fired at James Boone and Henry Russell had intentionally aimed at their hips to disable, not kill. The wounds, though severe, left them alive but writhing in agony on the ground and unable to move. The Indians tortured the unfortunate young men without mercy and made sport of their suffering by repeatedly striking them with knives and tomahawks to prolong the ordeal. Weakened by excruciating pain and loss of blood, the two vainly attempted to fend off the blades with their bare hands. Boone recognized his main assailant as Big Jim, a Shawnee acquaintance of his father’s. The young man pleaded with the Indian to spare their lives, but to no avail.4

The rest of the warriors split into small groups and continued the carnage. One group captured the horses or plundered the provisions and supplies while the other assailed those who had survived the initial onslaught. Charles, one of the black men, stood paralyzed with fear as two warriors claimed him as their captive. Although wounded, Isaac Crabtree and Samuel Drake fled into the woods and evaded capture. Adam, the other slave, escaped unscathed. From his hiding place concealed in the brush by the river bank, Adam watched the Indians unleash their anger on his companions. The other warriors, impatient to get away, shouted for the braves tormenting Russell and Boone to hurry. After they killed and scalped their victims, the assailants disappeared into the woods with their trophies. One of them left the bloodied war club by the bodies, the traditional sign that boasted the warriors’ triumph and warned enemies to pursue at their peril.5

The ill-fated party was part of an expedition planned and organized by Captain William Russell and Daniel Boone to “reconnoiter the country, toward the Ohio and . . . settle in the limits of the expected new government” of Vandalia. They had moved in three groups. Boone began the trek on September 25, when his and five other families left their homes on the Yadkin River in North Carolina. After entering Powell’s Valley in southwestern Virginia, they halted to rendezvous with a party led by William Bryan, Boone’s brother-in-law, which increased their numbers to about fifty men, women, and children. Whereas Boone and his neighbors moved their entire households, including baggage, furniture, domestic animals, and cattle, Bryan’s men planned to build houses and prepare their fields over the winter and then return to move their families to the new settlement in the spring. Boone’s enlarged column camped and waited for the others to catch up just north of Wallen’s Ridge, a few miles from the scene of the fateful incident.6

Boone had sent three members of his party, including his seventeen-year-old son, James, with John and Richard Mendenhall to Castle’s Woods to obtain tools, farming implements, and additional supplies. Located in the Clinch River valley, the community represented the largest and most distant of Virginia’s frontier settlements in the newly established Fincastle County and was home to Captain William Russell. With Russell’s assistance, the young Boone and the Mendenhalls acquired the needed supplies, plus additional cattle, horses, and pack saddles. On Friday, October 8, the captain sent them on their way, accompanied by his seventeen-year-old son, Henry Russell, two slaves named Charles and Adam, a hired man known as Samuel Drake, and an experienced woodsman named Isaac Crabtree, to help manage the convoy and cattle. They expected to reach the main body within two days. The next day, after gathering the last of their harvests, Captain Russell followed with thirty men from Clinch River, including his neighbor David Gass.7

They had agreed that Russell would assume overall command when he joined the group, while Boone served as the guide into the uninhabited area that the Iroquois called Kain-tuck-ee, or meadowland. A renowned frontiersman as well as a gentleman from a prominent family, Russell represented the natural choice for the leader. He had attended the College of William and Mary, served in the French and Indian War, and become a successful tobacco planter, militia officer, and justice of the peace in Fincastle County. Russell was seeking to claim land due him for his wartime service, and his reputation and leadership skills attracted enough volunteers to give the enterprise a better chance of success. Although Boone exemplified the skills of the consummate woodsman, had visited Kentucky on numerous long hunts, and had scouted their destination the previous winter, his name remained relatively unknown outside of the Virginia and North Carolina backcountry compared to Russell’s.8

By Sunday morning, Daniel Boone waited in restless anticipation for the arrival of his son’s caravan and Russell’s contingent from Clinch River. Earlier that morning, following an altercation with another emigrant, one man had quit the venture. While heading home along the Warriors’ Path, the deserter happened on the killing field by Wallen’s Creek. Fearful of continuing alone, he backtracked to the camp. As soon as the man arrived, Boone learned the news that a number of Indians had attacked “the rear of our company” and his oldest son, James, “fell in the action.” While Boone directed the rest of the men to prepare to defend the camp against a similar raid, Boone sent his brother, Squire, with a dozen armed men to investigate.9

Traveling in front of the Clinch River men with David Gass, William Russell arrived on the scene first to find Henry’s corpse “mangled in an inhuman manner.” As the grief-stricken father described, “There was left in him a dart arrow, and a war club was left beside him.”10 As soon as Squire Boone and his men arrived, they searched for any warriors who remained behind in ambush, and then began the grim task of burying the dead. Rebecca Boone, Daniel’s wife, had given Squire two linen cloths to use as winding sheets. Russell and Squire Boone wrapped their relatives’ remains in one and the Mendenhall brothers in the other, and laid them all to rest. The attack had scattered the cattle and caused such other damage at the main camp that the settlers now found themselves in extreme difficulty. Daniel Boone later recalled, “Though we defended ourselves, and repulsed the enemy,” the unhappy affair had so discouraged the whole company that few wished to continue to the Ohio. The men held a council to decide what course of action to pursue, took a vote, and “retreated forty miles, to the settlement of Clinch river.” While others returned home, Daniel and Rebecca Boone, who had sold their farm in North Carolina, remained at Castle’s Woods for the winter in a cabin on the Gass property.11

Several of the men scouted the vicinity but found no signs to indicate whether the missing massacre victims had survived. Crabtree was mentally scarred by the ordeal, but his physical wounds proved minor, and he managed to walk back to Castle’s Woods within a few days. The uninjured Adam, possibly disoriented and suffering from shock, took a week and a half to find his way home. The search party presumed the Indians had either killed or taken Drake captive, and no one saw him alive again. After his captors had herded Charles along for some distance, they apparently concluded that an enemy scalp served their purposes as well as a live captive, or possibly argued about who actually owned the prisoner and what to do with him. Scouts later found the man’s scalped body by the trail some miles distant from the massacre site.12

Once back at home, Captain Russell attempted to account for the dead and missing. He took depositions and compared survivors’ recollections with his observations of the detritus at the scene. The captain concluded that the Indian attackers had killed five white men and one black without provocation, and one white and one black man had survived. Russell reported the incident to his superior officer in the militia, Colonel William Preston, the county lieutenant of Fincastle County. The next summer, Virginia’s royal governor, John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, would cite the massacre, along with other incidents, to justify Virginia’s hard-line stand when addressing Indian delegations attending a general Indian congress at Fort Pitt.13

An account of the “inhuman affair . . . transacted on the frontiers of Fincastle [County]” appeared in the December 23 edition of the Virginia Gazette published by Clementina Rind. The article read in part like a military report. Captain Russell’s command, which had gone to “reconnoiter,” became “separated into three detachments.” The Indians attacked the smallest of them, killing five whites and one black. After the unexpected assault, the party retreated after “getting intelligence” of the enemy. The paper asserted that the story came from “good authority,” which suggested the Russell-Preston correspondence.14 A Baltimore newspaper carried a different account of the tragic event on November 27, preceding Rind’s by almost a month. Based on a description by “a gentleman of credit lately from New River in Virginia,” that version differed in some details such as the circumstances, as well as the numbers of participants and casualties. Several newspapers, including the Pennsylvania Chronicle and Universal Advertiser of Philadelphia, reprinted the second-hand version before the presumably more authoritative narrative even went to press in Williamsburg.15

Nonetheless, the two accounts renewed the colonists’ concern about continued depredations and caused alarm among backcountry inhabitants, those who planned to acquire land in the frontier districts, and Crown officers charged with keeping peace with the Indians. Wondering how hostilities might bear on the land patents promised him and other veterans for military service in the French and Indian War, Dr. Hugh Mercer of Fredericksburg, Virginia, wrote Colonel Preston to inquire if “the Massacre” could be attributed to the “Indian’s Jealousy of our settling near them, or to a private Quarrel.” He also asked if any party received “certain intelligence” as to what nation of Indians’ warriors had killed young “Mr. Russell.”16

Sharing Mercer’s concern, Major General Frederick Haldimand, Lieutenant General Thomas Gage’s second in command, who had assumed the duties as acting commander in chief of the king’s forces in North America while Gage was on leave in England, asked in a letter to Sir William Johnson, superintendent of Indian affairs for the Northern Department, to be informed of the identity of Indians who attacked Captain Russell’s party on its way to the Ohio. The general told Johnson that although “Some say they were Cherokees,” he rather suspected them to be members of the “Shawanese than any other.”17 Alexander McKee, posted at Fort Pitt as Johnson’s deputy superintendent for the Ohio Indians, heard of the incident from traders returning from downriver and recorded in his journal that another party of Shawnees had returned home from the frontiers of Virginia bringing “a Number of Horses; and . . . had killed Six White Men & Two Negroes.”18 Aware of unrest among the nations of the Ohio country after almost ten years of relative, albeit tenuous, peace, many thought another Indian war might be on the horizon.

Lord Dunmore initially suspected the Cherokees. He wrote to John Stuart, the superintendent of Indian affairs for the Southern Department—and Johnson’s counterpart—for his assistance in bringing the guilty parties of that nation to justice. In return, Dunmore told Stuart to assure the Cherokees he would take every step within his power “to prevent any encroachments on their Hunting Ground” by Virginians.19 Stuart informed Haldimand that the Cherokees’ “behaviour and professions” toward the British remained friendly. Although inclined to believe that none from that nation shared in any of the guilt, Stuart nonetheless recommended that Crown officials keep the Cherokees in “good humour,” but to be alert for any signs of hostility. He then asked Alexander Cameron, his deputy superintendent for the Cherokees, to investigate further.20

Cameron indicated that he had seen or heard nothing that would implicate the Cherokees in the Powell’s Valley massacre. Although a war party that had gone out just before the incident returned with the scalps of four white men, Tuckassie Keowee, the son of Oconostota, the “Great Warrior,” told Cameron that they had attacked, killed, and taken the scalps from some Frenchmen on the Wabash River after mistaking them for enemy warriors. Tuckassie then told Cameron that seventeen Delawares and three “Seneca [Mingo]” left the Overhill Cherokee town of Chota in early October. He said they went home through Kentucky by way of the Louisa River on the Warriors’ Path and may have encountered and killed the whites.21 In sworn depositions before Fincastle County magistrates, members of Boone’s main party identified two Cherokees among a group of Indians they saw in the area days before the massacre.22 Stuart eventually secured the conviction and execution of only one Cherokee man, leading some Virginians to complain that he had not pursued justice as vigorously as he should have.23

The incident caused little concern outside of Virginia and the western counties of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Williamsburg printers Alexander Purdie and John Dixon produced a newspaper that began operation before that of their rival, Clementina Rind, but which shared the name Virginia Gazette. Both appeared every Thursday and often ran articles that covered the same events. The day that Rind’s printed the story, the Purdie-Dixon Gazette made no mention of the ambush, even though they issued a two-page supplement to their December 23, 1773, edition. Under the dateline Boston, November 29, an anonymous author, presumably Samuel Adams, announced the arrival of the ship Dartmouth, laden with a cargo of 114 chests of detested tea, which he described as the “worst of Plagues,” shipped to the colonies by the East India Company in accordance with the Tea Act.24

BY LATE 1773, trouble had been brewing on the frontier for some time. Less than a month before the attack in Powell’s Valley, Superintendent Johnson sent a report to William Legge, second Earl of Dartmouth, the secretary of state for the colonies, stating that the settlers going from Virginia and seeking new settlements, leaving large tracts of unsettled country behind them, had caused much alarm among the Shawnees. Johnson believed that the Indians had little reason to complain as long as the settlers stayed within the “old claims” of Virginia and not the recently acquired land. The Six Nations of Iroquois and the Cherokees, the two most powerful Indian polities and nominal British allies bordering the thirteen colonies, had recently ceded or relinquished control of the newer claims by the 1768 Treaties of Hard Labor and Fort Stanwix, and the 1770 Treaty of Lochaber. Johnson explained that many settlers could “not be confined by any Boundaries or Limits” without a government presence to enforce Crown policies. While the lawless and disorderly among them committed “Robberies & Murders” and caused concern among the Indians, he conceded that even the law-abiding displayed a general prejudice against all Indians, which in turn caused young Indian warriors or hunters to seek revenge even when slightly insulted.25

Of all native peoples inhabiting the Ohio country in 1773, the Shawnee (or Shawanos), western Delaware (or Lenni Lenape), and Mingo (or Minqwe), lived closest to the Virginia settlements. Ironically, they were not indigenous nor had they lived in the region significantly longer than the neighboring colonists. Bands of Shawnees and several little known native tribes had inhabited the Ohio valley until the Iroquois invaded their homelands, destroyed their towns, and dispersed their people during the Beaver Wars of the seventeenth century.26 The Six Nations then used the conquered depopulated area as a hunting ground for many years before they permitted several bands, which had migrated from their homelands under the pressure of colonial expansion and intertribal disputes, to settle there under its dominion. Superintendent Johnson explained to General Gage that the [then] Five Nations “had conquered all, and actually extirpated Several of the Tribes there,” and placed the Shawnees, Delawares, and others on “bare Toleration in their Stead, as sort of Frontier Dependents,” and to act as a buffer for the Iroquois homelands.27

In order to better maintain control over their dependents and access to the hunting grounds, the Iroquois sent some emigrants from the Six Nations, mostly Senecas, to settle among the Ohio Indians. Whites knew these Iroquoian people as the Mingo, derived from a name the Delawares applied to all the members of the Iroquois Confederacy. After living removed from under the influence of their chiefs, many Mingo people began to view themselves as autonomous from their parent nations, but they generally remained obedient to the confederacy’s central council at Onondaga through the leadership of its local viceroy, the skilled diplomat and leading warrior Guyasuta.28

The Six Nations of Iroquois was arguably the most powerful Indian polity in northeastern North America at this time. In the sixteenth century, according to tradition, the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Oneida agreed to unite under the Great Law of Peace to become the Haudenosaunee, or People of the Longhouse. To Europeans, they became known as the Five Nations of Iroquois, and the Iroquois Confederacy, or League. Although each remained free to pursue its own interests as long as they were not in conflict with those of other member nations, representative sachems, or civil chiefs, from each moiety assembled around the central council fire at the Onondaga principal town to resolve internal disagreements, discuss issues of mutual concern, and decide on collective action. The Five Nations grew into a powerful political, military, and economic force that first destroyed its nonleague Iroquoian rivals and then struck at various Algonquin stock enemies. During the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the council admitted the Tuscaroras to the confederacy as wards of the Oneida—who represented them at the council fire—and the league thus became the Six Nations.

Victorious in numerous wars of conquest, the Iroquois Confederacy claimed suzerainty over vanquished nations and territory. Through those it considered subordinates and allies, the confederacy extended its diplomatic and economic influence and acted as a conduit for the British to native peoples deep in the interior through an alliance called the Silver Covenant Chain of Friendship.29 The Iroquois-British alliance proved mutually beneficial and enabled each to use the other’s strength and power—whether real or perceived—to leverage its own with friend and foe alike. Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1713), known as Queen Anne’s War in the colonies, other European nations recognized the Six Nations’ people as British subjects and their land within the king’s dominion. General Gage cautioned that believing the Six Nations had ever acknowledged themselves as being subjects of the English would be a “very gross Mistake.” The general believed that if told so, the news would not please the Iroquois to learn of that status. Gage therefore recommended that the British not treat them as subjects but as allies who accepted the king’s promises of protection from encroachment by either his European foes or his white American subjects.30

Of all Ohio valley Indian entities, the Shawnees arguably held the most hostility toward British interests. In 1742, Conrad Weiser, the Pennsylvania colony’s long-time Indian agent, described them as “the most restless and mischievous” of all the Indian nations. They, and to a lesser extent the western Delawares, felt oppressed by the imperious Six Nations, who looked on them as dependent or tributary peoples. The genesis of this relationship, according to Weiser, came after they suffered a decisive military defeat, after which the Delawares figuratively had “their Breech-Cloth taken from them, and a Petticoat put upon them” by the Iroquois. They humbly called themselves “Women” when they addressed their “Conquerors,” which the Six Nations also called them when they spoke “severely to ’em.” In less stressful conversations, the Iroquois called the Delawares “Cousins,” who in turn addressed them as “Uncles” in recognition of their subordinate status.31 When Weiser described the subordination of the Shawnees, he explained that it had happened according to a different process. Because the Iroquois had never conquered them, they never officially considered the Shawnees in the confederacy but described them as “Brethren” to the Six Nations. In return for granting permission to settle on land under their dominion, however, the Iroquois claimed “Superiority” over them, and for which the Shawnees “mortally hate them.”32

Reflecting this animosity, Shawnee representatives repeatedly told Superintendent Johnson and his deputies that the Iroquois Confederacy “had long Seemed to neglect them” and “disregard the Promise . . . of letting them have the Lands between the Ohio & the [Great] Lakes.”33 They complained that the Six Nations cared little for the interests of the native peoples they considered under their dominion and appeared more intent on pleasing the British and protecting their own interests when they negotiated matters of war and peace, or the cession and sale of land. The Iroquois ceded land west of the Blue Ridge, including the Shenandoah valley, to Virginia at the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster. Tachanootia, the Onondaga spokesman for the Six Nations, told those attending that treaty, “but as to what lies beyond the Mountains, we conquered the Nations residing there.” If the Virginians ever wanted to get a “good Right to it,” he continued, it must be only by his people.34 Although they disagreed on how far west that cession extended, after white settlers began to occupy it, the Iroquois granted Virginia the remaining land south and east of the Ohio in 1752 at the Treaty of Loggstown. As the Six Nations representative, Tanacharison, the “Half King” leader of the Mingoes and the Ohio country, speaking on behalf of the Six Nations council at Onondaga, signed a “deed” that recognized and acknowledged “the right and title” of the king of Great Britain to all the lands within the colony “as it was then, or hereafter might be peopled.”35

On both occasions, the Iroquois neither considered Shawnee interests nor recognized Cherokee claims to the same area. To counter the influence of their overlords, the Shawnee expended considerable diplomatic energy attempting to form their own “association” among the Ohio region Indians to help shake their dependency and oppose the military, economic, and political domination of the “6 Nations (& English).”36 In a somewhat duplicitous effort to convince other native peoples that they served as a channel for Iroquois policy while advancing their own interests, the Shawnees endeavored to draw the “Six Nations emigrants on Ohio,” the Mingoes, into their confederacy.37

An Algonquin language-stock people, the Shawnee nation functioned as a confederation of five semiautonomous tribal units, called septs, that shared a common language and culture: the Chilabcahtha, or Chillicothe; Assiwikale, or Thawekila; Spitotha, or Mequachake; Bicowetha, or Piqua; and Kispokotha, or Kispoko. Although the system had an uncertain origin, by the latter eighteenth century, each sept had its own council of elders that selected its chiefs and met at its principal town—whose name derived from that of the sept—and participated at a central council as well. Each sept could act independently as long as it did not create conflict with the others, while the central council of elders decided matters of mutual importance, especially those involving diplomatic, military, and economic activities with European or other Indian nations. 38

When they acted in concert, each sept assumed leadership in a certain facet of governance in which all others recognized its expertise. The two principal divisions, the Chilicothe and Thawekila, held responsibility for managing internal politics and led in matters that affected the tribes when they acted in unison. The Mequachake held responsibility for matters related to health and medicine, and provided healers. The Pequa answered the nation’s needs for leadership in spiritual concerns and rituals. Finally, the Kispokos provided the Shawnees with their principal war chiefs and led in military matters.39

Under the terms of the 1758 Treaty of Easton during the French and Indian War, the Six Nations granted the newly formed confederacy of Shawnee and western Delaware Indians living in the Ohio country a degree of independence, provided that they recognized continued Iroquois dominion over the land, including the exclusive authority to sell it to the British.40 Although the treaty affirmed Six Nations control over the land they inhabited or used as hunting ground, through the diplomatic skills of the Delaware chief Pisquetomen, the Ohio Indians demanded a boundary to separate Indian from British territory in return for a cessation of hostilities and renunciation of their alliance with the French. When they departed Easton for home, Shawnee and Delaware sachems understood that the British promised not to maintain military posts on Indian land in the Ohio valley after the war.

The Shawnees and other Ohio Indians welcomed the announcement of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 at the end of the Seven Years’ War, and viewed it as an affirmation of the promises made at Easton. The proclamation said “that the several nations or tribes of Indians with whom we are connected, and who live under our protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the possession of such parts of our dominion and territories,” and it reserved the land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Ohio River as their hunting grounds. As a means of more efficiently managing westward expansion, the proclamation directed the military commanders in chief and the governors of the thirteen colonies, “for the present,” to prohibit British subjects from establishing settlements within the boundaries of the colonial charters but beyond a line formed by the heads of any of the rivers that flowed toward the Atlantic Ocean from the west or northwest, or any other land in their territory, that the Indians had not yet ceded to or sold to the Crown, “until our further pleasure is known.” Although many British subjects had already settled in the frontier districts on land ceded before 1763, the proclamation put a halt to all purchases of Indian land by private interests. Thereafter, only official representatives of the Crown acting in their official capacity could conduct transactions to acquire Indian land in the context of formal treaties.41

These provisions reflected the convention European powers used in their efforts to colonize the New World, which became known as the Doctrine of Discovery. In principle at least, Europeans generally recognized the Indians’ right of original occupancy. In the context of colonial America, the doctrine enabled a nation to extend its imperial domain over land previously unknown to, or unclaimed by, other Europeans and thereby preempt the right of any others to do so. When a European nation acquired the unsettled colonial territory of a rival, whether by purchase, diplomacy, or military victory, it only acquired the preemptive exclusion until the Indians ceded or sold them the land.42

The British Crown and American colonists saw the acquisition of Indian land as the means of fulfilling their mission to spread civilization, defined as Anglo Christianity and English culture, across the continent. In his Second Treatise on Government, English philosopher and apostle of the Enlightenment John Locke wrote that “God and his Reason commanded him [man] to subdue the Earth, i.e., improve it for the benefit of Life, and therein lay out something upon it that was his own, his labour.”43 The colonists moving to the frontier found what they characterized as a vast “desert,” meaning a waste country, wilderness, or an uninhabited place, just waiting for them to “improve,” or “to advance nearer to perfection” and “raise from good to better.”44 They improved the land by clearing the forest and dividing it into parcels of privately owned property set apart by fences. The settlers altered the land for cultivating crops or grazing cattle and constructed homes, barns, and outbuildings. The new inhabitants established industry and commerce with mills, kilns, mines, and forges. The immigrant populations expanded and established villages and towns with churches, courthouses, jails, taverns, and shops. Finally, they connected their communities with other communities by roads, fords, bridges, landings, and ferries, to advance civilization.

According to Locke, “Land that is left wholly to Nature, that hath no improvement of Pasturage, Tillage, or Planting, is called, as indeed it is, wast[e].”45 American colonists looked to the British Crown, and their colonial governments, to acquire the largely uninhabited wasteland from the Indians, either by force or diplomacy, so they could obtain their own parcels to improve and make their own property. Benjamin Franklin, an American disciple of the Enlightenment, expressed this sentiment in his 1751 essay, “Observation Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, &c.” He described the filial relationship between the Crown and colonies in part by stating “the Prince that acquires new Territory, if he finds it vacant, or removes the Natives to give his own People Room” fulfilled a paternal obligation. Similarly, a man who invented “new Trades, Arts, or Manufactures” shared the credit with he who acquired land so that both “may be properly called Fathers of their Nation, as they are the Cause of the Generation of Multitudes.”46 The colonists’ land hunger should therefore not be characterized as simply motivated by greed but in the context of eighteenth-century attitudes as inspired by Enlightenment ideals.

Regardless of context, enlightened philosophies were alien to the native peoples. In contrast to their white neighbors, Indians believed in a mystical relationship between man and nature in which the Great Spirit, or creator, provided the land and the beasts on it for their use, but not for any one person to alter or possess. Had they been familiar with Locke’s work, Indians would have argued that land in which “all the Fruits it naturally produces, and Beasts it feeds, belong to Mankind in common.” Since these were produced by the “spontaneous hand of nature,” Indians would have maintained that the land needed no improvement.47 The Six Nations sachem Canassatego recognized this cultural divide when he addressed the Virginia commissioner at the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster. “Brother Assaragoa”—an Iroquoian word meaning Long Knife, or Big Knife, in reference to the ceremonial swords Virginia governors wore as a symbol of office and with which the Indians identified them—“our Customs differing from yours, you will be so good as to excuse us.”48 Although the Six Nations agreed to cede the land between the “back of the great mountains” of Virginia and the Ohio River at that treaty, he expressed the Indians’ concern on how the new inhabitants improved the land. When living near them, the settlers’ practice of raising domesticated animals became a source of contention because “white Peoples Cattle . . . eat up all the Grass, and made Deer scarce.”49

Similarly, at the Treaty of Easton in 1758, the Seneca sachem Tagashata, a Six Nations deputy speaking on behalf of all Indians, related that “Our Cousins [the Minisinks]” complained that they were dispossessed of a great deal of land due to “the English settling too fast” so that they “cou’d not tell what Lands [still] belonged to them” and forgot what they sold. He further maintained that the colonists claimed the wild animals as well as the land and no longer allowed the Minisinks to “come on . . . to hunt after them.”50 Indians often felt that even after they ceded land in friendship, white settlers still dealt harshly with them. With no corresponding concept of private property and land ownership, Indians believed that the game animals were still theirs or common to both. They maintained that when they sold land, they did not propose to deprive themselves of hunting wild deer. They discovered that the settlers not only claimed “all the wild Creatures” on the land but did not “so much as let us peel a single Tree,” or use “a Stick of Wood” for shelter or firewood. Understandably, many native people took great offense at such practices.51 Similar cross-cultural misunderstandings caused hard feelings, mistrust, and animosity and often led to conflict.

Many colonists did not wait for formal land cessions or purchases from the Indians. The Royal Proclamation caused dismay among those who already lived or had their eyes fixed on acquiring lands beyond the limits of settlement. They considered land between the Appalachians and the Ohio the fruits of victory over the French and their Indian allies, fairly won in a hard-fought war. Many Americans, including George Washington, understood that what he derisively called the “Ministerial Line” established by the proclamation had to be “considered by the Government as a temporary expedient.”52 The very wording—“for the present, until our further pleasure is known”—reinforced this sentiment. Otherwise, many argued, the provision for the governors of the provinces of North America to grant “without fee or reward” the land bounties promised to officers and soldiers for their wartime service, and the ten-year exemption from having to pay the same quitrents as on other purchased lands, would have been hollow.53 Furthermore, by calling it the ministerial and not royal proclamation, Americans did not fix the blame on the king but on ministers they believed had deceived him.

After the Crown issued the Royal Proclamation, William Johnson and John Stuart, superintendents of Indian affairs for the Northern and Southern Departments, respectively, requested the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, commonly called the Board of Trade, for permission to conduct negotiations with the Indians to identify and survey the actual boundary. Hoping to avoid another Indian war and satisfy native peoples as well as land speculators, settlers, and colonial officials, the Board of Trade issued its preliminary instructions in 1765. Specifically, the board directed the Indian superintendents to draw the line from Fort Stanwix, at the portage between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek in the north, south, and west to the Ohio River, then along its course to its confluence with the Great Kanawha River, proceeding up the Kanawha to its headwaters, then south to the border of East Florida. In early 1768, the Board of Trade’s president, William Petty (who was born William Fitzmaurice before his father changed the family name to Petty in order to inherit the earldom from his wife’s family), the Earl of Shelburne, transmitted the king’s command to complete the “Boundary line between the several Provinces with the various Indian Tribes . . . without loss of time.”54

Before any negotiations between Crown officials and Indian nations could begin, the British Indian Department’s officers had to mediate peace between the two powerful native polities bordering the colonies. After repeated requests by colonial officials of North Carolina and Virginia on behalf of the Cherokees, Superintendent Johnson invited that nation and the Iroquois Six Nations to send their representative sachems to meet at Johnson Hall, his baronial manor in the Mohawk valley, to discuss ending the war between them. In February 1768, both sides agreed to sign the peace treaty.55 The Cherokee representatives returned home well pleased and satisfied with the council’s results, which opened the way for the next round of negotiations.

In the Northern Department, Indians from several nations began arriving at the abandoned British military post of Fort Stanwix in August. Eventually, three thousand four hundred Indians, including representative sachems, leading warriors, and their families, assembled. They represented the Six Nations and their several dependent and tributary tribes, as well as native peoples from outside of the Iroquois Confederacy such as the Seven Nations of Canada and the Wyandots.

Johnson convened the council. Negotiations began among the various Indians and with William Franklin, the royal governor of New Jersey; commissioners from the colonial governments of Pennsylvania and Virginia; and representatives of the “Suffering Traders” of Pennsylvania. Led by William Trent and Samuel Wharton, the last group sought land cessions for themselves and fellow Indian traders as compensation for the property they lost and other financial hardship incurred during Pontiac’s War of 1763 to 1766. Although he attended as Johnson’s deputy superintendent for the western Indian nations, George Croghan also had a private interest in the proceedings as one of the aggrieved traders. Dr. Thomas Walker and Andrew Lewis represented Virginia interests, until Lewis departed on October 12 to attend the council with the southern Indians at Hard Labour. The discussions lasted from September 20 until October 24, when the participants began work on formulating the treaty. The sachems of the Six Nations presumed to act as proprietors of all Indian land and affixed their totems to the Boundary Line Treaty and “a deed executed for the lands to the Crown of Great Britain” on November 5, 1768.56 The final agreement not only established a boundary line on behalf of the Iroquois themselves but for the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, and others. Although representative chiefs from those entities attended, the Iroquois signed on their behalf and ceded their interests in land east and south of the Ohio River to the British.57

As required by the Royal Proclamation, Johnson, a representative of the Crown acting in his official capacity, purchased the ceded land from the Six Nations, who claimed dominion over it. In return, the favored Iroquois received the entire £10,460 British payment, much to the consternation of the Indian people who actually lived or hunted on the ceded land. The new boundary line ran from just west of Fort Stanwix south to and along the Delaware River, then west to and along the West Branch of the Susquehanna to the upper Allegheny Rivers, then followed the latter downstream to Fort Pitt at the Forks of the Ohio River, then down the Ohio, passed the mouth of the Great Kanawha, to the mouth of the Tennessee River, then known as the Cherokee or Hogohege. The treaty therefore extended the boundary prescribed in the Board of Trade instructions much farther west. Part of the cession included the Indiana Grant as compensation to the suffering traders for their losses. To justify extending the cession, the Six Nations’ sachems declared “it to be our true Bounds with the Southern [Cherokee] Indians & We Do have an undoubted Right to the Country as far South as that River which makes our Cession to his Majesty much more advantageous than proposed.”58

Meanwhile, at Hard Labour, South Carolina, Stuart had reached an agreement with the principal Cherokee chiefs that established the southern Indian-colonial boundary on October 17, 1768. To the great relief of British subjects who had already settled there despite the Royal Proclamation, the Cherokees relinquished their claims to all lands between the Appalachian Divide and the Ohio, but only as far as the Great Kanawha River. However, many colonists had settled, and the lands acquired by the Loyal Company of Virginia for speculation were beyond this line. More importantly for Virginia interests, the Treaty of Hard Labour negated much of what the colony had gained in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. 59

When Virginia’s commissioner, Andrew Lewis, reported on the “ensuing Congress with the Cherokees,” the members of Virginia’s Colonial Council described the proposed boundary as “highly injurious to this Colony, and to the Crown of Great Britain.” They based their objections on grounds that it gave the southern Indians, or Cherokees, “an extensive tract of Land” between the Kanawha and Cherokee Rivers that the Six Nations had owned and ceded at Fort Stanwix. Virginia officials further maintained that Stuart essentially gave the Cherokees land, “a great part of which they never had, or pretended a right to, but actually disclaimed.” The council directed Lewis to return to South Carolina, accompanied by Walker, to inform Stuart of the importance of a just boundary before he ordered the line surveyed. Otherwise, Virginia would not cooperate in determining a boundary until it received more explicit and precise instructions from the king.60

Superintendent Johnson’s Fort Stanwix boundary did not join to form a coherent demarcation with that settled by Stuart in the Treaty of Hard Labour. Johnson maintained that the Six Nations could cede any of the land along that boundary as they held dominion over it by right of conquest, despite claims by those Indians who inhabited or hunted it. Therefore, the Six Nations ceded land on the Susquehanna and Allegheny inhabited by the Delawares and Munsees, as well as the Cherokee and Shawnee hunting ground in Kentucky, and even some arguably Cherokee country in present-day Tennessee, by the treaty signed at Fort Stanwix.61 Johnson’s explanation also affirmed the Virginia position.

Although he expressed displeasure with Johnson for not complying with his instructions and exceeding his authority, Lord Hillsborough, minister of the then newly created Secretariat of State for the Colonies, nevertheless communicated the royal ratification of the treaty and boundary, except for certain private grants, in December 1769. That same month, fifty-three men petitioned Virginia’s governor Norborne Berkeley, fourth Baron Botetourt, for permission to “take up and survey” sixty thousand acres on the Cumberland River from the lands situated on the east side of the Ohio “having lately been recognized by the Six Nations of Indians” as conveyed to “his Majesty’s Title.”62

Ratification of the Fort Stanwix boundary required Stuart to renegotiate the southern boundary due to the great loss and inconvenience it caused the many British subjects who inhabited lands that the Cherokees had not ceded but the Iroquois had. Along with commissioners from Virginia and North Carolina, Stuart convened a meeting with sixteen Cherokee chiefs on October 5 at Lochaber, South Carolina, the home of Alexander Cochrane, his deputy for that nation. By the eighteenth, the Cherokee leaders signed the deed relinquishing all claims to the land from the North Carolina and Virginia border west along the Holston River to a point six miles east of the Long Island of the Holston, then north by east on a straight line to the Ohio at the mouth of the Great Kanawha.63

Although an improvement, the arrangement still did not please the Virginians much more than the Treaty of Hard Labour had. Authorized by a resolution of the General Assembly to request Stuart to negotiate “a more extensive Boundary,” Governor Botetourt urged the southern Indian superintendent to immediately negotiate a treaty with the Cherokees in which Virginia would gain the cession of those lands to which the king had already consented in the Fort Stanwix Treaty. With the necessary appropriations passed, Botetourt commissioned Colonel John Donelson to survey the new boundary as soon as possible after the Indian superintendent and commissioners concluded the new treaty.64 Botetourt did not live to see it. After he died on October 15, 1770, William Nelson, president of the colonial council, assumed the role of acting governor.

Stuart informed Cochrane that the treaty had not pleased the Shawnees either. They sat as “the head of the Western confederacy” formed for the purpose of maintaining their property in the lands the British obtained from the Six Nations at Fort Stanwix and preventing white people from settling there.65 Johnson and the Iroquois leaders feared that the Mingoes, residing in the neighborhood of the “disaffected tribes,” would feel increasingly alienated. They did not want their emigrants to fall under the influence of the Shawnees, whom they considered no real friends of the Six Nations, to the point where they “followed other councils.” Seeking to exert renewed authority on their kin, Johnson called for a congress of deputies from the Six Nations to meet with the Shawnees, Delawares, Wyandots, Miamis, and others to put a halt to their attempts to seduce the Mingoes, or Six Nations on the Ohio, from their allegiance to the Iroquois Confederacy.66

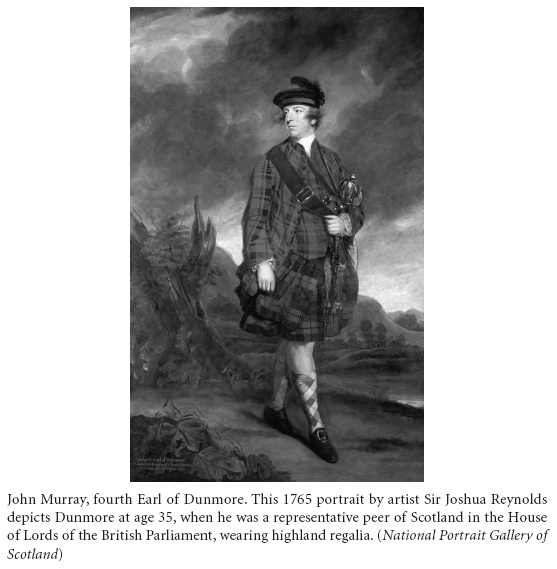

WITH THE unexpected death of Governor Botetourt, Lord Hillsborough selected John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, then serving as royal governor of New York, to succeed him in Virginia. The new governor’s father, William Murray, influenced by his wife Catherine’s Nairne relatives, and much to the embarrassment of the rest of the Murrays, had joined the losing side in the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. William Murray served the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart, or Bonnie Prince Charlie, as a vice chamberlain, or assistant to the manager of the royal household. Although too young to serve in the rebel army, John left his studies at Eton when his father secured him the honorary position of a “Page of Honour” to the prince. After the forces loyal to King George II decisively crushed the rebels in the April 1746 battle of Culloden Moor, William initially evaded capture, but eventually surrendered to the king’s forces. Indicted by a grand jury, he stood trial “by Reason of his having been concerned with the late Rebellion.”67

Fortunately, William’s brother and son’s namesake, John Murray, the second Earl of Dunmore, and a “General of Our Foot” in the British army, intervened on William’s behalf. The Crown spared William from execution for “High Treason,” as well as “all other Treasons, Crimes and Offenses” committed before December 22, 1746, for which he stood convicted. The government commuted the death sentence to confinement. Two years later, in 1748, George II granted William a royal pardon with “license to reside in Beverly, at Yorkshire,” which enabled him to succeed the unmarried John as third lord in 1752, when his elder brother died leaving no heirs.68

In 1749, the year after the Crown pardoned William, John brought his brother’s son into the British army in a manner most appropriate and befitting a young Scottish aristocrat. John, the second Earl of Dunmore, who had served many years as the colonel of the regiment, purchased his nephew and successor to the earldom an ensign’s commission in the 3rd (Scottish) Regiment of Foot Guards. Under the unique dual-rank system of the day, the young John Murray’s appointment not only included a much sought after membership in the elite unit but a captaincy in the British army as well.69 When William died in 1756, Captain John Murray became the fourth Earl of Dunmore, with an inheritance that included the additional hereditary titles of Viscount Fincastle and Baron of Blair, Monlin, and Tillimett.70

Despite the advantages he enjoyed, Dunmore experienced a series of disappointments as a young officer in pursuit of military distinction and advancement. As soon as Great Britain declared war on France in 1756, he unsuccessfully sought field assignments. Despite the assistance of well-connected friends and relatives, and possibly tainted by his father’s treason, his requests for posting to the Anglo-German army commanded by Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Lunenburg on the European continent or assignment to that of Brigadier General James Wolfe in North America went for naught. Except for participating in a few raids against the coast of France, he took part in no campaigns of any note. Although Dunmore served in an army engaged in a desperate global conflict, he gained little combat experience and no distinction.71

Dunmore’s fortunes began to change in 1761, when his fellow Scottish aristocrats elected the brash thirty-year-old to a seven-year term as one of the representative peers of Scotland in the House of Lords. That same year, his friend and army comrade William Fitzmaurice Petty, a military aide-de-camp to King George III, inherited the title second Earl of Shelburne and a seat in the Lords on his father’s death. Although nothing prevented serving officers from sitting in Parliament, Dunmore, frustrated in his pursuit of a military career, informed the well-connected Shelburne of his intention to “resign all thoughts of the army” in 1762.72

Dunmore eventually received the appointment, and briefly served, as royal governor of New York in 1770. He thoroughly relished his short time as governor and took the opportunity to acquire a sizable holding of land and other wealth in that colony. In an era when realizing personal profit from one’s political position did not necessarily constitute a conflict of interest or corruption, Dunmore made the most of his appointment. Although it was considered a promotion, he reluctantly accepted the governorship of Virginia but delayed his arrival in Williamsburg for several months. He assumed his new post in September 1771.

COLONEL JOHN DONELSON set out on his mission to survey and mark Virginia’s new western border in fall 1771. Cochrane and “several chiefs of the [Cherokee] Indians concerned,” including Attakullakulla, the “Most beloved” or principal chief, whom the British called Little Carpenter, accompanied the surveyors. After they had surveyed the line, Virginia’s new governor reported to Secretary of State Hillsborough that the new line did not run exactly according to the instructions and took in a larger tract of the country than the Treaty of Lochaber had defined. During the process of surveying, Donelson secured the several Cherokee chiefs’ agreement to adjust the negotiated boundary from that as drawn on the map. The arbitrary line ran through difficult and unremarkable ground, which the Indians described as not good for hunting anyway. The new surveyed boundary followed easily recognizable terrain features that could never be mistaken and proved less costly to survey. Still short of the limits established by the Fort Stanwix boundary and less area than Governor Botetourt desired for the colony, Virginia’s new area extended to the Louisa (or Kentucky) River. From its confluence with the Ohio, the new boundary followed the Louisa to its northernmost fork, ran west along the ridge of mountains to the headwaters of the Cumberland, and then east to the Holston River where it met the cession agreed upon at Lochaber. Although not a formal treaty, the arrangement became known as the Great Grant, or the Cherokee Treaty of 1772.73

In February that year, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation that created a new county, named Fincastle in honor of one of Dunmore’s hereditary titles, by incorporating areas of Botetourt County plus the land acquired by the recent boundary-line adjustments.74 In April, a group of anxious settlers petitioned the Virginia Assembly for a large grant on the Louisa River. By October, the governor and council ordered a Commission of Peace to establish the county court and appoint justices of the peace, as well as create the militia establishment and commission its field officers.75

While the Iroquois and Cherokee relinquished their claims and collected the purchase prices (although evidence exists that the Cherokee may never have received the £500 promised them), none of the diplomatic actions addressed the concerns of the Shawnee for the loss of their hunting ground. For all intents and purposes, especially as colonists, Crown officials, and the Six Nations viewed it, the Ohio River represented the new boundary between the British colonies and Indian country. Not surprisingly, the Shawnees disputed the treaties and looked upon any white encroachment as an invasion. As early as April 1771, Superintendent Stuart informed Lord Hillsborough that the “dissatisfaction of the Western tribes . . . at the extensive cession of land at the Congress at Fort Stanwix” caused them to form confederacies and alliances with other nations. In consequence, they were “indefatigable” in sending messengers and making peace overtures to the Cherokees in order to balance the power of the Iroquois, whom they held responsible for their loss. Stuart further expressed the opinion that the extension of the colonial boundaries into the Indian hunting grounds had “rendered what the Indians reserved to themselves on this side of the mountains of very little use to them.” Deer were already becoming scarce because of the influx of white hunters and erection of new settlements.76

After reading the reports from the Indian superintendents, General Gage informed Lord Hillsborough that the Ohio tribes had become “discontented” because great numbers of whites had crossed the Alleghenies to settle between the mountains and the Ohio, “so near to the Indians as to occasion frequent quarrels.” The general nonetheless had confidence in Johnson’s assurance that the Six Nations “resolved to manifest their fidelity to the English” in enforcing the treaty and “bring the Western nations to good order.”77

The British army relinquished responsibility for frontier security when it ordered a number of posts abandoned and demolished, and their garrisons redeployed to eastern cities. General Gage informed William Barrington, second Viscount Barrington, the secretary at war, “If the Colonists will afterward force the Savages into Quarrells by using them ill, let them feel the Consequences, we shall be out of the Scrape.”78 The evacuation of regulars from Fort Pitt on October 10, 1772, pleased the Indians but caused a vacuum of authority that both Pennsylvania and Virginia sought to fill. Pennsylvania’s Assembly, controlled by the Quaker Party, would never approve the proposal for raising and supporting even a small number of troops that Lieutenant Governor Richard Penn sought to garrison Fort Pitt in the place of the king’s forces.79

BOTH VIRGINIA and Pennsylvania claimed jurisdiction of the region between the Monongahela and Ohio Rivers, including the strategic Forks. Virginia’s government considered the area a part of Augusta County, established in 1738. When Pennsylvania established its Westmoreland County west of the Laurel Ridge in 1772, its boundary overlapped a portion of western Augusta. Virginia’s claim ultimately rested on the London Company’s corporate charter of 1609, and the royal colony charter that replaced it in 1624, which fixed its area between two hundred miles north and south of Old Point Comfort on the Atlantic, then west to the “Western (Pacific) Sea.” Except for specified cessions of land to other colonies at various times, by 1773, Virginia’s dominion still stretched in a widening vector to the west and northwest, encompassing present-day Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. Pennsylvania based its claim on William Penn’s 1661 proprietary charter for a colony between the Delaware River on the east to five degrees of longitude on the west.80 This description left the western border open to four possible interpretations. The western limit could be defined either by an irregular boundary that mirrored all points on the Delaware, or a fixed straight line corresponding to either the point farthest east, farthest west, or at the median of the two. Any of these solutions for determining Pennsylvania’s western boundary encroached on land included in Virginia’s charter.

In an attempt to confirm the grants awarded the suffering traders at Fort Stanwix, William Trent and Samuel Wharton traveled to England in 1769 and met with some influential parties to form the Grand Ohio Company. Backed by investors in London and Philadelphia, including merchant and House of Commons member Thomas Walpole and American scientist, author, and printer Benjamin Franklin, who acted as an agent in Parliament for Pennsylvania and other provinces, they approached the Board of Trade with a plan to establish a new inland colony on the recently ceded Indian land. Originally to be called Pittsylvania, they changed the name to Vandalia in honor of Queen Charlotte, George III’s wife, as she purportedly descended from the Germanic tribe the Vandals. The proposed venture immediately complicated matters on the frontier.

The Board of Trade cited “the necessity . . . for introducing some regular system of government” to a part of Virginia that the commissioners believed was too far from the civil government at Williamsburg. The distance from that capital, the argument ran, rendered the people living there “incapable of participating of the advantages” of being part of that colony. Therefore, they recommended that the region be separated from Virginia and incorporated into Vandalia by letters patent under the Great Seal of Great Britain. They envisioned the new colony’s area as bounded on the west, north, and northwest by the Ohio River, from the border of Pennsylvania to a point opposite the mouth of the Scioto, then down the Louisa to its headwaters and eventually the Holston River, and on the east by the Allegheny Mountains.81 Although Lord Hillsborough disapproved, the Privy Council overruled him and forwarded the Vandalia plan to the king. The Virginia government opposed the new creation since Vandalia’s area would come at the expense of territory granted by the colony’s royal charter and recently acquired by the Indian treaties. George Croghan, who expected a settlement based on his suffering trader status, stood to gain either way. Had George III assented to the new colony, Vandalia’s boundaries would have encroached on the territory of, and created competing land claims with those issued by, Virginia. The king, however, never signed the charter.

As soon as Dunmore assumed the governorship in 1771, he began receiving petitions for patents on western lands. Presiding over the largest, wealthiest, and most populous British colony on mainland North America, Dunmore seemed eager to establish himself as the king’s viceroy and protect the interests of the colony over which he presided. In a personal letter to Hillsborough, he viewed the granting of patents and “settling . . . some of the vacant lands which the new boundary-line now offers . . . as a means of ingratiating myself very much with the people of this colony.” Dunmore’s ambitions were not unlike those of other colonial officials in using the advantage of government office for personal gain, and he sought to acquire land “advantageous to my family” while in Virginia.82

Dunmore found that he and George Washington shared common interests in this regard, and they were on friendly terms. Both aspired to acquire land and gain a return on the investment through speculation. As speculators and other land-hungry colonists joined veterans seeking to redeem their bounties, they desired to have their claims “legally surveyed and patented” as soon as possible.83 Many settlers had also started flooding into the recently ceded areas since the last war. In a letter to his brother Jonathan, the busy twenty-year-old surveyor George Rogers Clark wrote that “this C[o]untry settles very fast.” With the new boundary treaties signed and ratified, Clark added, “the people is a settling as low as ye Siotho [Scioto] River 366 [miles] Below Fort Pitt.”84

In an effort to establish Virginia authority and bring some order to the situation on the frontier, Governor Dunmore authorized Captain Thomas Bullitt to organize a party to survey the land in northern and eastern Kentucky. Leading about forty men, he started down the Ohio from the Kanawha River. On entering Shawnee country, Bullitt visited the principal Shawnee town of Chillicothe and met with the chief, Keiga-tugh-qua, whom the English called Cornstalk, and other leaders. After informing them that the land on the south bank “had been sold to the white people by the Six Nations and Cherokees as far down the Ohio as the mouth of the Cherokee River,” he continued on his way. After reaching the Falls of the Ohio in July, he remained into August to lay out the settlement that later became Louisville, Kentucky. Bullitt’s visit understandably alarmed the Shawnee. Meeting at Fort Pitt, Shawnee deputies addressed Guyasuta, the Seneca chief and diplomat representing the Six Nations’ interests in the Ohio country and exercising authority over the Mingoes, and Alexander McKee, Sir William Johnson’s deputy superintendent, to express their dismay that “our nations had not been considered when the purchases were made.”85

Meanwhile, Dunmore “thought it might conduce to the good of His Majesty’s service” to personally visit the “interior and remote parts” of the colony. The governor planned to go in the summer of 1773, when not much provincial business would be conducted in Williamsburg between the sessions of the General Court.86 George Washington, actively lobbying for the governor to honor the land grants promised to the veterans of the Virginia Regiment by Governor Robert Dinwiddie and the General Assembly in 1754, and to open the area for settlement, invited Dunmore to visit Mount Vernon on his way. If the governor wished to leave as early as the first of July, Washington offered to accompany his lordship “through any and every part of the Western Country” he thought proper to visit. Washington recommended and arranged for fellow Virginia Regiment veteran William Crawford, a good woodsman who was familiar with the lands in the region, to act as their guide. In addition, Washington offered to contact the now-retired long-time deputy superintendent of the western Indians, George Croghan, to arrange a meeting with some local tribal leaders.87

Unfortunately, tragedy struck Mount Vernon on Saturday, June 19, when Martha “Patsy” Parke Custis, Martha Washington’s child from a previous marriage, died unexpectedly of an attack of epilepsy. Expressing being “most exceedingly sorry,” the governor offered his condolences to the bereaved stepfather and especially the grieving Mrs. Washington for the loss of the “poor young lady.” Dunmore understood that Washington could no longer accompany him but communicated his intention to pay his respects to the mourning family in person at Mount Vernon on his way.88

Dunmore’s mission apparently had two purposes. First, he wished to exert Virginia’s jurisdiction over the area to counter the Pennsylvania claims. Second, he opposed the creation of Vandalia and would show the Privy Council and Board of Trade that the frontier districts did not fall beyond the reach of his government’s civil and military protection. Formulating his plan, he sought the support of local residents, including some who had accepted Pennsylvania civil offices, like his guide Crawford, who served as the president and chief magistrate for Westmoreland County. While many Virginians lived there, others considered themselves Pennsylvanians. When Dunmore visited his home on the Youghiogheny River, Crawford provided the governor with information about the region and locations of the best land. In return, Dunmore assured Crawford that he would receive the patents for the land Virginia owed him for his wartime service.

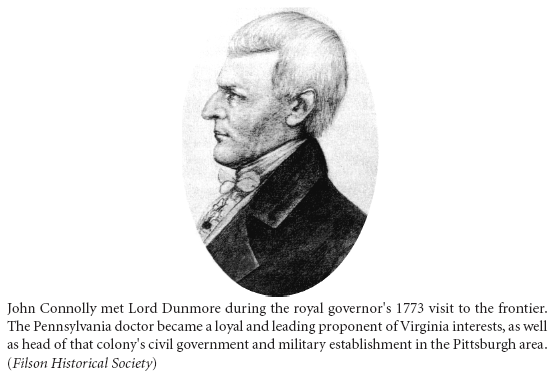

On his arrival in Pittsburgh, Dunmore found that the neighborhood had “upwards of ten thousand people settled [but] had neither magistrates to preserve rule and order among themselves, nor militia for their defence in case of sudden attack of the Indians.” The withdrawal of the British garrison the previous year left no agency to keep order, and the fort had been partially demolished with the remains in such disrepair that it had little defensive value. Yet, Dunmore noted the presence of an Indian settlement directly opposite to the town on the far side of the river, which presented “the utmost necessity of such establishment.” He found many inhabitants who agreed with him, and he claimed that people flocked around him and begged him to appoint magistrates and militia officers in order to remove “these onerous inconveniences under which they labored.”89 To further put their concerns at ease, he assured everyone that his government would honor land patents they received from other valid authorities. Dunmore thus won over a number of Pennsylvanians, including Colonel Croghan, as one of the suffering traders, and Dr. John Connolly, both of whom stood to gain much in the Vandalia project.

ALTHOUGH HIS high forehead, beak-like nose, and steel-eyed gaze gave Connolly a hawklike appearance, Thomas Jefferson described the thirty-two-year-old doctor as “chatty” and “sensible to physic,” or the practice of medicine, but who confided that he had always aspired to be a soldier. Connolly proudly stated that he had served as a volunteer—meaning he was unpaid—in two campaigns. These included the British attack on Martinique in the West Indies during the Seven Years’ War and on the frontier during Pontiac’s War. This participation afforded the aspiring officer an opportunity to observe the “great difference between the petite guerre [guerrilla war] of the Indians, and the military system of the Europeans.” Not taking the experiences he gained for granted, it was essential and necessary for a good soldier in this service to be a master of both modes of warfare. In addition to experience, Connolly’s military service had also earned him a patent for land.90 Dunmore enhanced Connolly’s interest with the promise of an additional two thousand acres at the Falls of the Ohio and invited him to discuss the matter with him more fully in Williamsburg in the autumn. An excited Connolly wrote to George Washington that since “Lord Dunmore hath done us the honor of a visit,” he had come to share the Virginian’s high regard for the governor as “a Gentleman of benevolence & universal Charity.” In September, Washington wrote to congratulate the governor on his safe return to the capital. He also hoped to build on the governor’s interest in land acquisition following his “Tour through a Country,” which even “if not well Improv’d” had at least been “bless’d with many natural advantages.”91

Meanwhile, Superintendent Johnson wrote William Legge, second Earl of Dartmouth, secretary of state for the colonies, and president of the Board of Trade, with “intelligence” received from Fort Pitt. His deputy, Alexander McKee, reported that “a certain Captain Bullet with a large number of people from Virginia” had gone down the Ohio beyond the proposed boundary of Vandalia to survey and lay out lands “which are to be forthwith patented.” The news disturbed the Indians “a good deal” and left the Shawnee, in particular, “much alarmed at the numbers who go from Virginia in pursuit of new settlements.”92

Coincidentally, King George III and the Privy Council issued new guidance concerning the disposal of His Majesty’s land on April 7, 1773, which Dunmore received in early October. The king and his ministers realized that the authority to grant Crown lands conveyed by each governor’s commission and instructions needed to be further regulated and restrained. Additionally, those receiving grants of Crown land should also be subjected to other conditions than previously enumerated. Therefore, George III ordered all governors, lieutenant governors, and other persons “in Command of his Majesty’s Colonies in North America” to cease issuing any warrants of survey or to pass any patents for lands, or grant any license for the private purchase of any lands from the Indians without special direction from the king until further notice. The new regulation exempted only veterans of the regular service, not provincials, entitled to the military grants as prescribed in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, although Dunmore vigorously advocated for the latter.93

Three weeks had elapsed following McKee’s warning about Shawnee restlessness before a party of nineteen braves made their way through the Kentucky hunting grounds on their way home from Chota in Cherokee country. Having just attended a congress where representatives from several nations discussed the continued white encroachment on those very hunting grounds, the warriors’ blood was up, and they were spoiling for a fight. When they crossed paths with eight men leading cattle and packhorses, the Indians seized the opportunity to strike. After a quick and violent attack on the morning of October 10, 1773, that left six of the eight dead, fear of a new war spread along the frontier.