CHAPTER 3

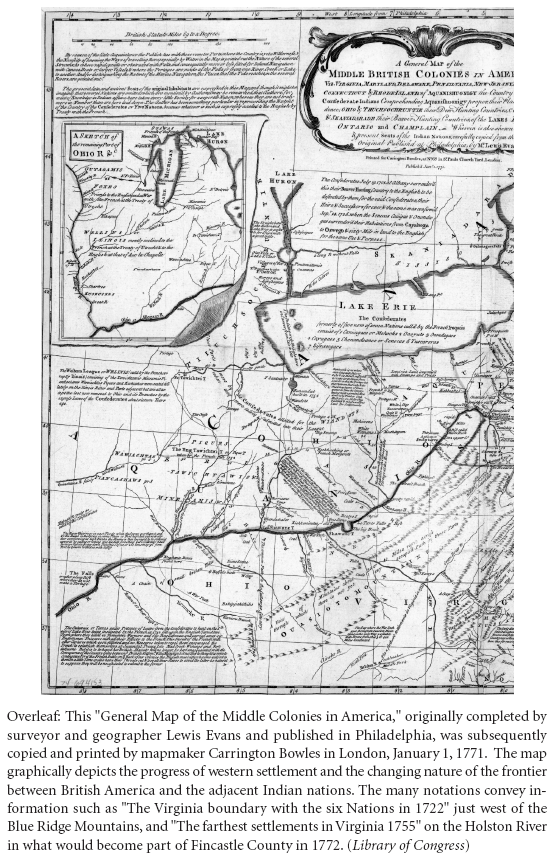

A War Is Every Moment Expected

Increasing Frontier Violence

April–May 1774

BY EARLY APRIL, backcountry inhabitants and work parties spread the word that “the Indians had placed themselves on both sides of the Ohio, and that they intend war.” Virginians were not alone in believing that a conflict seemed imminent. The area’s Pennsylvanians, however, held the Virginians, not the Indians, responsible for instigating the potential hostilities. Before John Connolly arrested Aeneas Mackay and sent him and two fellow Pennsylvania magistrates to jail, Mackay had expressed his concern in a letter to Governor Penn that the Virginia captain commandant had “parties of armed men patrolling through our streets daily.” Their activities had so alarmed the Indians living across the river from Pittsburgh that they expected the whites to initiate “hostility . . . against them and their country.”1 For their part, the Virginians feared they would not only have to fight the Shawnees in the north, possibly in confederation with other Ohio Indians, but the Cherokees in the south as well—either separately or in an alliance. Connolly and his associates continued to cite Virginia’s ability to defend the community from invasion and contrasted it to Pennsylvania’s lack of a permanent military establishment, whenever news of violence reached Pittsburgh. Just such an incident then occurred downriver.

The Shawnee chiefs who George Croghan and Alexander McKee invited to Pittsburgh at the end of 1773 to discuss the growing frontier unrest became increasingly impatient and concerned. The chiefs’ staying as guests at Croghan Hall to ensure their safety had not prevented irate settlers from firing an occasional angry shot in their direction. Acts of hostility caused some of the chiefs to have “disagreeable Dreams” and heightened their feelings of foreboding. On March 8, after hearing “bad News from our Town” about the increasing violence between whites and Indians, the chiefs told their host that they were anxious to leave. When the final meeting of the council convened, also attended by several Six Nations and Delaware chiefs and officials from both colonies, McKee made a final attempt to defuse the causes of conflict. He urged the Shawnee headmen to do their best “to preserve the peace and Tranquility of this Country” when they returned home. The Shawnees replied that “your wise Men” should also be acquainted with the “very great” numbers of white people who were migrating beyond the boundaries established for their settlements. The settlers, as well as the activities of surveyors and land jobbers, were “overspreading the Hunting Country of our Young Men.” When the Shawnees’ young men found the woods covered with “white people & their Horses” where game had once been plentiful, the chiefs could do little to prevent the “evil Resolutions” that resulted. When young warriors became disappointed in their hunting, maintaining peace would prove impossible.

The expressed desires of the white people to prevent war had so far not impressed the Shawnee headmen. What they had seen and witnessed since their arrival only confirmed their fears. Distant musket shots had harassed them all winter. They had observed the militia “constantly assembling . . . with red Flaggs [sic]”—meaning the red colonial ensigns used as regimental standards—and learned that the “Long Knife [Virginia] people” proposed to build a large fort lower down the river that summer. They challenged that if the Virginians truly desired peace, they would have “laid aside” such warlike preparations. In not doing so, they had convinced the Shawnees that war remained uppermost in most white people’s minds.

In concluding the council, McKee told the Shawnee leaders that bad news from their towns concerned whites and Indians alike. He urged them to use their “utmost Abilities in restraining evil dispos’d people & promoting every good thing,” and discourage the warlike intentions of their “foolish young men.” For his part, McKee promised that he and the colonial officials would do the same among the white settlers. He further assured the chiefs that they would find the “Great-men” of British America, in their “Uprightness & Wisdom,” receptive and ready to redress their complaints with the utmost candor. He concluded by telling the headmen they could expect British and colonial leaders to afford them every justice for the transgressions of unfriendly white people so that they would have no need to resort to arms. Finally, McKee promised to communicate their concerns to William Johnson, his superior and the British official Indians trusted most.2

Throughout the early weeks of spring, numerous parties of white men looked for land on the south bank of the Ohio for a variety of purposes. Settlers sought acreage on which to build new homes and lives, while others went to ply a variety of trades. Surveyors measured patents and recorded plats for private owners and county land offices. Parties of craftsmen and laborers under contract with the owners built new or repaired existing structures on previously acquired property. Land jobbers acted as speculators and brokers, seeking available property that they could buy and sell for others at a profit. The combined efforts of these and other groups contributed to the common goal of improving what they saw as a vast, uninhabited country, or desert. Amid the activity, news of unfriendly encounters with Indians and reports of warlike acts continued, as the frontier kindling began to smolder.

On Thursday, April 14, three white employees of trader William Butler departed Pittsburgh in a canoe loaded with goods to exchange with the Shawnee for pelts. After traveling about forty-five miles down the Ohio, they stopped for the night near the mouth of Beaver Creek. Along the way they encountered four Cherokees, three men and a woman, to whom they showed some silver items. The next morning, before they could resume their journey, the Cherokees “waylaid” them on the river bank and opened fire. After they plundered the cargo and took the most valuable merchandise, the robbers escaped, leaving a trader named Murphy dead and another named Stephens wounded; conflicting versions reported the third man had either died, went missing, or escaped. A group of land jobbers arrived on the scene and offered their assistance. Benjamin Tomlinson, a settler who lived nearby, dug Murphy’s grave while Dr. William Wood dressed Stephens’s wounds.3

As soon as news of the incident reached Fort Pitt, Connolly embodied a detachment of militia for active service to pursue the Cherokees and instructed the commanding officer to apprehend and bring them back to stand trial for murder, if possible, or otherwise treat them as declared enemies. The militiamen recovered the traders’ canoe and a considerable share of the property but could not locate the offending Indians. Connolly followed the next day with another detachment and transported the wounded man back to town. The captain remarked, “This incident occasion’d a great deal of confusion and as I imagin’d it woud be improper to allow an act so insolent to pass over unnotic’d.” When the evidence suggested the Cherokees had headed toward the Shawnee towns, Connolly recommended that McKee send that nation’s headmen a demand that they apprehend the outlaws.4 Guyasuta, who had just returned from an Indian congress at Johnson Hall with messages for restoring “good order to the Southward,” warned the other tribes not to join the Shawnees in starting any fights with the Virginians. Guyasuta then sent a message to Mingo Town, the “small Village of Six Nations [Mingo] Indians living below Logs Town,” encouraging them to have some warriors join forces with the militia in the attempt to apprehend the renegade Cherokees.5 Perhaps indicative of the contrasting views held by those who learned of the incident, Virginian John Floyd described it in military terms as a “skirmish,” while Deveraux Smith of Pennsylvania wrote since they were Cherokees, he believed the incident was a simple robbery, not an act of war.6

McKee followed Connolly’s instruction and sent messengers informing Shawnee and Mingo leaders of the Beaver Creek incident and alerted them that he believed that the offending Cherokees were headed in their direction. Imploring them to capture and send “those Murderers” back to Pittsburgh for trial, the deputy Indian superintendent explained how such action served their own best interest. He reminded them not only of their promises to do everything they could to preserve the “Chain of Friendship” with the British and do justice but that they bore some responsibility for rectifying the situation since the bandits had stayed with them as their guests before committing the crimes. The Shawnee, he said, “must be looked upon in some degree accountable” for the Cherokees’ behavior. McKee also appealed for the Shawnee leaders to view the attack as an outrage committed against their own people, since the traders furnished them with “Necessaries.”7

On April 20, after receiving a complaint from the Delaware chief Coquethagechton, or Captain White Eyes, that some Virginians had insulted and abused him, Connolly composed a public notice and had it printed as a broadside announcement posted throughout the district. He also instructed some traders to take copies downriver and post them in the “most public Settlements” along the Ohio. The notices informed all who read them that “certain imprudent people” inhabiting Virginia settlements had “unbecomingly ill-treated” and threatened the lives of some friendly and well-disposed Indians. He cautioned everyone to avoid such conduct in the future and urged them to act friendly toward any “Natives as may appear peaceable” since the “Tranquility of this country” depended on it. The same day, Croghan informed the captain commandant that the Shawnees had become generally “ill disposed and might possibly do mischief.” In response, Connolly composed a “Circulatory Letter” to the inhabitants of the district that advised them of the situation and recommended that they “be on their guard against any Hostile attempts” by unfriendly Indians.8 Many took Connolly’s letter as either a warning that hostile Indians would likely strike at any time or that fighting had already begun, and therefore a de facto declaration of war.

Meanwhile, two days after the attack on the traders, the last few of the Shawnee chiefs who had spent the winter at Croghan’s departed Pittsburgh. Before long, they passed Little Beaver Creek on their way to the Muskingum or Scioto. Over the course of the next week, McKee learned that “Eighteen Canoes of the Six Nations [Mingoes]” and others who lived near Logstown and Big Beaver Creek had also passed Little Beaver Creek. Many of them had apparently abandoned their villages and followed the Shawnees downriver.9 Arthur St. Clair observed that “a small party of these [Mingoes],” much to the consternation of the Six Nations council at Onondaga, lived near the Shawnees and were now “in a manner incorporated with them.”10

A few days later, John Floyd wrote to Colonel Preston about an incident in Fincastle County where he previously reported “3 or 4 Indians down the River were thought to be killed” in a skirmish with thirteen settlers, but that proved to be an unfounded rumor. When he discovered the facts, he wrote that according to one of the men that should have been in the engagement, the Indians had only robbed them.11 Reports from elsewhere in the Ohio valley brought additional news and rumors. Reverend David Zeisberger at Schönbrunn, the Moravian mission village near the Delaware towns on the Muskingum River, wrote that he had learned from John Bull, also known as Cosh, and John Jungman that a party of Mingoes had stolen fifteen horses from settlers below Logstown, and, “The white people began to be much afraid of an Indian war.”12 They had good reason to, as several violent incidents occurred almost simultaneously at different points along the Ohio.

Despite the danger, William Butler still needed to move the peltry from the Shawnee towns to Pittsburgh. He engaged a Delaware and a Shawnee to help the recently injured Stephens take trade goods to the Indians and bring the pelts to his factory. On Sunday, April 24, about a week after the affair near Beaver Creek, Stephens and his companions paddled their canoe into the channel and headed downriver toward the mouth of the Scioto.13

Guyasuta and McKee met in Pittsburgh the next day to discuss the great deal of confusion and discontent many of the Indian tribes had recently expressed concerning Connolly. They cautioned the captain commandant that it could prove very detrimental to the public interest to allow spirituous liquors to be sold or carried into the Indian towns at this critical time. Until then, the traders had either disregarded or not taken seriously the deputy Indian superintendent’s earlier requests to limit the amount of alcohol they shipped to the natives. As the reports of violent incidents increased, so did the demand for liquor. McKee and Guyasuta tried to impress on Connolly that “the Addition of Rum” only served to increase the Indians’ disorderly conduct.14 They therefore sought governmental action to limit the availability of alcohol to the Indians. Meanwhile, in Williamsburg on April 25, Dunmore had signed the proclamation that obliged the district’s free adult male residents to be prepared to embody as militia in order to repel an expected Indian invasion, and he sent it by express to Connolly at Pittsburgh.15

BELOW THE Great Kanawha, at the same time that the incident at Beaver Creek occurred, a group of Shawnee warriors observed from across the Ohio River as Lawrence Darnell and the six members of his survey party landed their canoes on the south bank. The men constituted an advanced detachment of Floyd’s survey expedition. Whether unaware, or aware but not alarmed, that Indians had watched them and crossed to their side of the river, they casually unloaded their instruments and supplies and made camp. Suddenly, the warriors surprised and captured the men, robbed them of everything they had, and took them back across the river to a Shawnee town for tribal judgment. For three days, their captors discussed what they should do with the trespassers. Much to their captives’ surprise and relief, the Indians told them in English that although Croghan had allegedly directed them to “kill all the Virginians they could find,” but only “rob & whip the Pennsylvanians,” they could go free. The Indians also ordered them to get off the river immediately.16

After several days making their way on foot, the men reached the camp of the main body of Floyd’s survey party, located about thirty miles below the Great Kanawha near the mouth of the Little Guyandotte River. Darnell told Floyd what had happened. Floyd, a deputy surveyor and undersheriff for Fincastle County, relayed the news of the attack in a message carried by Alexander Spottswood Dandridge to Colonel Preston on April 26. The deputy surveyor also asked his superior to let him know as soon as possible after the four runners that Russell had dispatched returned with confirmation on the actual location of the border with the Cherokees so none of his men would inadvertently cross it and further provoke the ire of that nation. Although several survey parties had gone out that spring, tensions with the Indians had increased so much by the last week of April that Floyd observed “our Men are almost daily Retreating.”17

Dandridge and his party left the survey camp “under great apprehension of danger” from the Indians and brought Preston the additional news that three other men from the survey party had earlier left camp with the completed plats of George Washington’s two–thousand-acre claim on the Great Kanawha, but no one had heard from them since. With tensions on the frontier escalating, Dandridge also carried Floyd’s request for Preston to send someone to bring the surveyors’ horses, then stabled at the Greenbrier settlements, forward to the surveyors’ camp to facilitate their withdrawal.18

While Darnell’s party underwent their capture and walked back to Floyd’s camp, a group of about eighty or ninety men encamped up the river near the mouth of the Little Kanawha also had an encounter with hostile Indians. One of them was twenty-one-year-old George Rogers Clark, who had established a farm on Grave Creek a short distance from the settlements on Wheeling Creek. A trained surveyor, Clark had thoroughly explored the area of the longest straight-line segment of the Ohio known as the Long Reach the previous year. He had since joined with a group planning to establish a new settlement in Kentucky. Clark and his associates had previously agreed to meet at a rendezvous to assemble the necessary supplies and equipment, and descend the river in a single body in the spring. While waiting to embark, they learned that Indians had fired on a small hunting party out looking for game for their group about ten miles farther down the river. The hunters fortunately managed to fend off the attackers, and all returned to camp unhurt. “This and other circumstances,” Clark later recalled, “led us to believe the Indians were determined on war” in spring 1774.19

In retribution, the settlers decided to attack the Indian town of Horsehead Bottom, which was on their way to Kentucky on the north bank near the mouth of the Scioto. They planned to descend the river, land above their objective, move across country, and then assault the town from behind on its land side. Having all the equipment and men necessary, they only lacked a competent leader. Michael Cresap happened to be in the area, about fifteen miles upriver from their camp. Cresap had some hands, including a group of eight to ten carpenters and laborers who were busy clearing and improving property claimed by George Washington, and also settling a plantation on which Cresap intended to settle his own family. In an earlier meeting, Cresap indicated that after he established his land, he intended to follow Clark’s party to Kentucky. Remembering the conversation during the discussion, one of the settlers in Clark’s party proposed that they ask Cresap to become their leader, to which all unanimously agreed.20

Born in Frederick County on Maryland’s colonial frontier in 1742, the son of the famous pioneer Colonel Thomas Cresap, Michael received a formal education at the school of a Rev. Mr. Craddock in Baltimore County. A veteran soldier, although too young for regular or provincial service in the French and Indian War, he grew up in the militia and fighting Indians in the skirmishes that punctuated the tenuous peace that followed 1765. Michael Cresap had initially followed his father’s lead as an Indian trader, operating from the family home at Shawanese Old Town on the Potomac River, east of the Wills Creek site of Fort Cumberland. He relocated to Redstone in 1772, where he established a new store and became a land developer as well as a recognized leader of the Virginia faction in the border dispute with Pennsylvania.21

The news of recent Indian depredations had alarmed Cresap and his men, and they combined with other work parties in the area for mutual defense and support until their force numbered about thirty. Hunters from both groups encountered each other somewhere in between the two camps, and in the usual exchange of information that ensued, the men from Clark’s party informed their counterparts that their companions intended to ask Cresap to serve as their captain. They hurried to tell their leader the news before the messenger from the southern group arrived with the actual request. Once informed, Cresap headed down the river to meet the members of his new command.

After he arrived, the Kentucky-bound settlers held a council to hear Cresap. Clark remembered “to our astonishment our commander-in-chief . . . dissuaded us from the enterprise”! Cresap told them that they had all heard about Indian depredations lately committed on the south bank. With all the candor he could muster, their new captain cautioned them that “the appearances were very suspicious,” and although alarming, he felt there was no certainty that a war had yet actually started. He had no doubt that they could carry a successful attack on the Indian village as had been proposed, but whether they attacked at that time or waited, he believed a war would indeed erupt before much longer. The only difference in choosing to attack sooner rather than later would cause them to justly receive the blame for starting it. If they insisted on voting in favor of an immediate attack, Cresap offered to disregard his own reservations and call the men from his camp to combine their forces and lead them into battle. He then proposed an alternative. Cresap asked them to take post with his men near the Wheeling Creek settlement and wait to hear news that confirmed whether a war had actually begun. If there were to be no Indian war that season, he would join them as they proceeded to Kentucky. After a short deliberation, all the men of Clark’s band agreed with Cresap.

While on the way to Wheeling Creek, the settlers met a party of Indians led by the Delaware chief Bemino, known to whites as John Killbuck Sr. Now in his sixties, Killbuck had become well acquainted with white people along the frontier. Although he proved a ruthless enemy in past wars, many frontier inhabitants believed the chief had become a reliable friend in the peace that had ensued. While Clark and the group’s other leaders went across the river to meet with Killbuck, Cresap remained on the south bank for fear he might be tempted to kill the Indian out of revenge. According to Cresap, the Delaware chief had waylaid his father many times as he traveled the Ohio area as a trader.

When he reached Wheeling, Clark noticed “the country being well settled thereabouts,” but strangely “the whole of the inhabitants appeared to be alarmed.” Many families from the surrounding countryside had abandoned their isolated homes and sought refuge in the more-densely settled part of the region. To prevent panic and offer protection, Cresap organized his and the local adult male inhabitants into an ad hoc military unit. Clark described it as a “formidable party,” since all the hunters and men without families living in the area also joined. Although Cresap offered to send out scouts to provide early warning and security, nothing he said persuaded the refugee inhabitants to return to their homes. It did not take long for Captain Commandant Connolly in Pittsburgh to learn of the presence of Captain Cresap’s company at Wheeling. He sent a message that made Cresap aware that a war with the Indians could break out at any time. Connolly therefore requested Cresap to keep his men stationed in the area for a few days, or at least until the question of whether there would be peace or war had been answered. He then confided to Cresap that he was waiting for runners to return from the Indian towns with the latest intelligence. Cresap and his men resolved to stay and comply with Connolly’s orders to “be careful that the enemy should not harass the neighborhood.”22

Meanwhile, back at Fort Pitt, Connolly copied Lord Dunmore’s April 25 proclamation and posted it throughout the district, along with his own circular letter for the people of West Augusta to be on their guard. Although it may have had the effect of steeling the officers and men of the militia for the fight, Connolly primarily intended his letter to encourage families not to abandon their homes. While it is unlikely Dunmore’s proclamation reached the frontier settlements before the end of the month, Connolly’s earlier letter, carried downstream by traders and surveyors, most likely appeared at the Wheeling Creek and other settlements by Monday, April 25. People all along the Ohio had already learned that hostile Indians had effectively closed the river to traffic and threatened parties of surveyors, land jobbers, and laborers on the south bank. Some therefore perceived the Connolly letter as a declaration of war, while others took it as confirmation that war with the Shawnees had already begun. The news affected frontier inhabitants, and the divergent attitudes persisted throughout the conflict. Where some settlers greeted the news with dread and prepared to abandon their homesteads for less vulnerable locations, others resolved to stay in spite of the risks. The letter also inspired some local militia commanders, as well as emergent leaders and their paramilitary bands, to take direct action against any Indian invaders without waiting for orders from a competent authority if they perceived a credible threat to their communities.23

Clark later maintained that Cresap received a message in which Connolly begged him to use his influence to have the men of his party protect the country about the settlements by aggressive scouting until the inhabitants fortified themselves by building blockhouses or stockades at their homes. Taking Connolly’s letter as official notification that hostilities had commenced, Cresap called his men together for a council of war and read it to them. In the same manner as Indians did, the men planted a war post and declared war against the Shawnees as they struck it with their hatchets, one man at a time. He then summoned all the traders in the area to inform them of the situation as he knew it and cautioned them about the dangers of navigating the river.

Later in the evening, they received unconfirmed reports that marauding warriors had killed two local residents. The news prompted some of Cresap’s men to go hunting for Indians with revenge on their minds; and someone brought in two scalps that night. As happened too often, emotions overruled reason. Some men cared little for determining whether the provocative incident had actually occurred, to what tribe the alleged assailants belonged, or the nature of their disposition toward whites. While the Shawnees presented the most likely threat, to some settlers, all Indians were enemies. Many Virginians also believed the Pennsylvania traders were just as bad as, if not worse than, hostile Indians since they profited from supplying muskets, powder, and lead to the warriors who used them against backcountry settlers.24

The next morning, Cresap’s men learned that a canoe piloted by three men had been sighted as it approached from upriver. Believing they could be Indians intending to cause trouble, Cresap voiced his intention to “way lay and kill” them. Led by Ebenezer Zane, who was a land developer and the founder of Wheeling, a minority of the company’s members opposed taking unilateral offensive action for fear of provoking a wider conflict. Considering their argument, the majority sided with Cresap and prepared for action. Two men, named Brothers and Chenoweth, joined the captain. They launched a canoe and paddled upriver to investigate and possibly engage the suspected threat. As it drew closer, Cresap and his companions moved to intercept the boat.25

The three in the southward bound canoe were William Butler’s employees, including a Shawnee, Delaware, and the previously wounded Stephens, who had left Pittsburgh a few days before on this second attempt to reach the Scioto towns. When he saw Cresap’s canoe paddling upstream toward them, Stephens feared it might be hostile Indians like those who had attacked him at Beaver Creek, and so paddled toward the south bank to avoid a confrontation. As the traders headed for the riverbank, someone concealed in the weeds on shore fired a shot that struck and killed the Shawnee. A second shot killed the Delaware. Stephens threw himself into the water. When he noticed three white men paddling the canoe in his direction, he swam toward them. After they helped him aboard, he learned that one of the men was Cresap, who, when asked, denied knowing anything of what happened to the traders in the canoe. Later, after he returned to Pittsburgh, Stephens told McKee that he was “well Convinced” the men who shot and killed his Indian companions were Cresap’s “Associates.”26 As Cresap and his men drew alongside the abandoned canoe, Brothers and Chenoweth ruthlessly scalped the lifeless Indians and pushed their bodies into the river. Taking the trader’s canoe in tow, the three paddled back toward the landing near camp. When Zane “saw much fresh blood and some bullet holes” in the canoe, he inquired on the fate of the two Indians. Brothers and Chenoweth answered they had fallen overboard.27

On Wednesday, April 27, five canoes carrying fourteen Indians went down the river early in the day, unnoticed by Cresap’s men. These were most likely some of the Shawnee chiefs returning from the council held at Pittsburgh. A settler named McMahon came to camp and informed Cresap that they had stopped at his home earlier in the morning asking for provisions, which he refused to give them. McMahon warned the Indians that some whites, alarmed by the depredations hostile warriors had recently committed in the area, had killed two Indians in the neighborhood the day before, and he urged them to be cautious. Taking his advice, the Shawnees used the large island off Wheeling to mask their movement from observation and passed down the western channel without being sighted. Soon thereafter, someone brought word that several canoes full of Indians were sighted on the north bank between the mouths of Pipe and Captina Creeks; or from eight to fourteen miles below Wheeling, and opposite Grave Creek. Stephens later claimed hearing Cresap “use Threatening Language against the Indians,” saying “he wou’d put every Indian he met with on the River to Death.”28

The captain gathered fifteen volunteers, loaded into canoes, and pursued the Indians to the mouth of Pipe Creek. Having landed and hidden their canoes on the bank until hardly visible from the river, and suspecting they would be followed after leaving McMahon’s, the warriors took position in the bushes on the shore and “prepared themselves to receive the white people.” Cresap’s men headed toward shore, landed, and advanced against their foe. In the ensuing skirmish, the Indians stubbornly disputed every inch of ground as they retreated. Clark recalled that a few were wounded on both sides, while others said that the volunteers took one Indian scalp but suffered one casualty when “Big Tarrence” Morrison sustained a serious hip wound. The Indians finally broke contact and retired into the woods, leaving their loaded canoes for Cresap’s men to capture. Clark observed that the plunder included “a considerable quantity of ammunition and other warlike stores,” in addition to trade goods, which Stephens enumerated as sixteen kegs of rum, two saddles, and some bridles.29

Once back at Wheeling, Dr. Wood treated and dressed Morrison’s wound as the rest of the company discussed their next move, and Cresap sent Connolly a report on what his men had accomplished. When he heard of it, McKee asked Connolly to send an express to Cresap asking what provocation caused him to take his actions and to desist from any further hostilities until he investigated and settled matters, if possible. The Indian Department deputy also dispatched messages to the chiefs, inviting them to attend another council at Pittsburgh as soon as possible in hopes of averting a war.30

When questioned by McKee, Stephens claimed that he heard Cresap remark, “if he cou’d raise Men sufficient to cross the River, he wou’d attack a small Village of Indians living on Yellow Creek.” Clark’s recollection confirmed that the men assembled at Wheeling decided to march the next day, Thursday, April 28, and attack that same Mingo camp. After they had advanced about five miles in the direction of Yellow Creek, Cresap ordered his men to halt for rest and refreshment. He again surprised his followers when he began to question the others “on the impropriety of executing the projected enterprise.” A number of those in the group, including Clark, had visited the intended target earlier in the year. They realized, or assumed, the collections of dwellings represented a camp for a hunting party, not a town. Essentially a temporary village, the camp consisted of shelters and baggage to adequately sustain the hunters, as well as women and children, for an extended period away from their permanent town. War parties, in contrast, traveled light and unencumbered to permit the warriors to move and strike quickly, and without exposing their families to danger. After some reflection, the men agreed with Cresap that the Mingoes they intended to attack, unlike the Shawnees who constantly caused trouble, had indicated no hostile intentions against the settlements. “In short,” Clark said, “every person seemed to detest the resolution we had set out with,” and they returned to Wheeling that evening.31

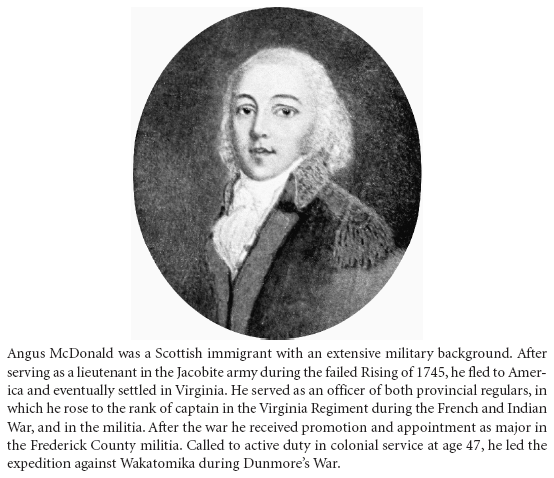

When he arrived back at camp, Cresap found Angus McDonald waiting for him. Educated in Glasgow, the forty-six-year-old Highlander had left his native Scotland following the defeat of the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion and settled near Winchester. He was a competent soldier, and his military career since arriving in the colonies included service as a captain in the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. In 1769, he was appointed major of the Frederick County militia. Returning from a trip downriver to survey the two thousand acres of his military land grant, McDonald paid Cresap a visit to discuss the military situation on the frontier before continuing homeward. After they finished and McDonald prepared to re-embark, Cresap, Clark, and a number of the others made ready to decamp and head toward Redstone.

Before McDonald shoved off, several men gathered on the bank saw traders John Gibson, Mathew Elliott, and Alexander Blaine descending the Ohio with a cargo of provisions and goods bound for the Shawnee towns on the Scioto. Those on the river bank hailed the traders and requested that they put ashore because they had “disagreeable news to inform them of.” On landing, Gibson recalled they encountered approximately 150 men, including Major McDonald and Dr. Wood. The men cautioned the traders about the dangers of heading farther downriver at that time and recounted the series of violent incidents between whites and Indians that occurred in the preceding weeks. Then they added the most recent news, which they had just learned. A work party improving land near the Great Kanawha had encountered and killed all the members of a Shawnee hunting party. Believing an Indian war imminent, the men took the thirty horses loaded with pelts and other plunder from the Indians and fled cross-country toward the relative safety of the Cheat River settlements to escape retribution for the massacre.

Gibson did not believe the story. He had left the Scioto for Pittsburgh earlier that month, after all the Shawnee hunting parties had returned. None of them lost any men or reported any violent incidents. To verify, Gibson invited some of the men at Wheeling to accompany him to a place called Canoe Bottom on Hockhocking Creek, where a few members of his company worked pressing skins and building canoes. If these workers were no longer present, they could conclude that the rumor of war was verified and that everything was not right on the frontier. Although Wood and one other man agreed to accompany him, the rest sent someone to consult Cresap. While waiting, some of Gibson’s hosts “behaved in a most disorderly manner” and even threatened to kill him and his companions, saying “the damned traders were worse than the Indians and ought to be killed.”

When Cresap arrived at the scene early on Friday morning, Gibson informed him what he had proposed and what some of the men said in reply. Cresap spoke with them for about an hour but could not convince any of the men to accept Gibson’s proposal. Cresap then personally advised Gibson not to proceed down the river. He confided that he believed the men in the camp “would fall on and kill every Indian they met on the river.” Although they had chosen him as their commander and attacked the Indians at Pipe Creek, Cresap said he would no longer serve as their leader or even continue to stay with them. Instead, he revealed to Gibson his intention to lead his work party, with Clark and some of his associates, “across the country to Red Stone to avoid the consequences.”

Despite the warning, Gibson and his companions proceeded by water to the Hockhocking. When they reached Canoe Bottom they found men working on canoes and everything as peaceful as expected, before they continued to the Scioto towns by going over land. When they arrived, Gibson, Elliott, and Blaine heard the Shawnees talking of several recent murders committed against the Indians on the river.32 At the same time, although Cresap had dissuaded his followers from attacking the camp at the mouth of Yellow Creek, someone else prepared for an engagement there. The smoldering situation on the frontier was about to ignite.

Those Mingoes living at the mouth of Yellow Creek included relatives of a Cayuga leading warrior named Talgayeeta, whom whites knew as Logan or James Logan. His many white acquaintances remarked on the friendship and hospitality he had always shown them. There is also reason to believe that he was white and adopted into his Indian family as a child. Logan had grown up in Shamokin, an Indian town near the Forks of the Susquehanna, where his father, the Oneida chief Shikellamy, represented Six Nations authority to the tributary and dependent tribes, such as the Delaware and Shawnee, living in the area.33 He was also a diplomat who represented the Iroquois Confederacy’s interests with the Pennsylvania government. In that position, Shikellamy developed such high esteem for the Pennsylvania colonial secretary, James Logan, that he chose him as his son’s English namesake.34

Directly across the Ohio from the Mingo camp stood a white settlement called Baker’s Bottom. It took its name from Joshua Baker, who had established a home and farm where he lived with his wife Elizabeth, or Lucy, and his brother-in-law, Nathaniel Tomlinson. Baker also kept a tavern and store, which became the meeting place for neighbors and a source of refreshment, entertainment, sundries, and rum for river travelers, as well as friendly Indians, despite McKee’s recommendation. A pregnant Indian woman, Logan’s sister (or other close female relative), Koonay, regularly crossed the river to visit Lucy Baker, who kindly gave her milk for her young children. After receiving Connolly’s circular letter warning settlers to be on their guard, Baker and other residents decided to evacuate their families from the vulnerable location to Catfish Camp until the situation became less volatile. According to some later accounts, their sense of urgency increased on Friday, April 29, when Koonay warned Lucy that some Mingoes, angered by the recent killings of Shawnees by Cresap’s band, planned to cross the river to kill all the white people. When Lucy informed Joshua, he called on his neighbors and friends for assistance.35

Upward of twenty or thirty men, mostly from the neighboring Cross Creek area, responded and arrived before morning. They included the Greathouse brothers, Daniel and Jacob, John Sappington, George Cox, Edward King, Michael Myers, and Lucy’s brothers Nathaniel, Joseph, and Benjamin Tomlinson. The latter Tomlinson had buried Murphy, the trader murdered by Indians at Beaver Creek earlier in the month. The boisterous Indian-hating Daniel Greathouse took charge and devised a ruthless plan. Most of the men would remain hidden in the “back apartment” of the Bakers’ house until they determined the Indians’ intentions. If the Mingoes “behaved themselves peaceably,” the men agreed, “they should not be molested.” If they proved hostile, the whites would “shew themselves and act accordingly.”36

On Saturday, April 30, the same day Cresap and his followers left Wheeling for Redstone, five Indian men and two women crossed the Ohio to Baker’s Bottom. Some accounts attributed their arrival to the Mingoes’ daily routine. Others maintained that Daniel Greathouse invited the Indians when he went over earlier in the morning to reconnoiter the warriors’ strength. The visitors included Logan’s sister Koonay, brother Taylayne, called John Petty by the English, as well as Taylayne‘s son, Molnah. As soon as the unarmed Indians got out of their canoes, all but Logan’s brother went into Baker’s tavern for rum. They were all soon intoxicated. Baker, Cox, and Nathanial Tomlinson stayed outside with Taylayne as the rest of their party remained concealed. At one point, Taylayne entered the Bakers’ house uninvited and took a military coat and a hat belonging to Nathanial Tomlinson down from where they hung on the wall. After donning the clothes, the Indian, “setting his arms akimbo began to strut about,” shouting, “look at me, I am a white man!” When Tomlinson demanded that he return the coat, Taylayne allegedly attempted to strike him while saying, “white man, son of a bitch.” When Tomlinson threatened the Indian, Cox advised against taking rash action, saying it would cause a war. Wanting no part of what was about to transpire, Cox left the group and hid in the woods. Although Tomlinson tried to avoid further confrontation, the Mingo’s behavior increasingly irritated Sappington. Not able to stand it anymore, he “jumped to his gun” and shot Taylayne as he left the house still wearing the hat and coat.37

The rest of the white men emerged from their hiding place. King rushed to the wounded Taylayne as he lay writhing in agony, drew his knife, and said, “Many a deer have I served this way.” He ended the man’s life and took his scalp.38 Others rushed and overpowered the drunken Indians in the building and shot every one—male and female alike. Daniel Greathouse proceeded to remove scalps from the warriors he killed and attached the bloody trophies to his belt. As she bled to death, Koonay pleaded with Jacob Greathouse to spare the life of the baby girl strapped to the cradleboard on her back. When the murder spree ended, every Indian except one had been killed. Only the two-month-old baby, the daughter of Logan’s sister and the trader John Gibson, survived.39

As they surveyed their handiwork, the men noticed two canoes, one with two and the other with five Indians aboard, paddling across the river. Either coming to investigate the fate of their friends after hearing the gunfire or confirming Koonay’s warning, Sappington described the braves as “stripped naked, painted, and armed completely for war.” The whites took position behind trees and logs along the riverbank and waited for the approaching warriors. As the lead canoe came within a few rods of shore, shots rang out and killed both occupants at close range. Sappington later claimed he killed and scalped one of them himself. The Mingoes in the second canoe turned about and paddled back for the north shore. Shortly thereafter, according to the memories of some participants, two more canoes appeared carrying eleven and seven armed and painted warriors, respectively. They attempted to land below the whites’ position, but the settlers engaged them with “a well-directed fire.” In the ensuing skirmish, some participants claimed, they killed one warrior who fell dead on shore, and recalled that they killed two and wounded two in the canoes before the Mingoes broke off the engagement and retired, returning fire as they went. Baker later remembered that Greathouse and company killed twelve Indians, including two women, and wounded either six or eight others. In contrast, Indian runners told Moravian missionary Heckewelder that nine had been killed and two wounded.40 Regardless of the correct butcher’s bill, Greathouse and his ruffians brutally murdered innocent people, including at least two, if not three, of Logan’s relatives.

News of the massacre spread quickly on both sides of the Ohio, through white settlements and Indian towns alike, with some variations added to the gruesome details. Some of them recounted that the self-appointed leader, Daniel Greathouse, had at first wanted to attack the Indian camp. After crossing the river on a reconnaissance, he found too many warriors to overcome with the numbers of volunteers he had assembled. Instead, he decided on a stratagem. Purporting to be their friend, Greathouse invited the Indians to cross over the river and share some rum. He told Baker to give the Indians all they could drink and that he and the others would assail them after they were intoxicated.41 In another version, while five of the Indians drank to intoxication, Daniel and Jacob Greathouse challenged the two sober warriors to a contest of shooting at marks, or targets. When they heard the reports of firearms indicating the men had shot the drunken Mingoes at the tavern, the Greathouse brothers took aim at their marksmanship competitors. Because the Indians had already fired, they stood holding empty weapons in their hands, and fell easy victims to the ambush.42 In the most disturbing and enduring of the variations, as the dying mother pleaded with the men to spare her little girl, Jacob Greathouse aborted Koonay’s unborn baby from her womb with his hunting knife, then killed and scalped the infant. In a final act of cruelty, he hung the child’s lifeless body on a tree. Whether any of these are accurate, embellished, or exaggerated accounts does not change the heinousness of the acts. What is ironic, however, is that most reports accused Michael Cresap of responsibility and named Daniel Greathouse only as an accomplice.43 The man who had convinced his followers not to attack the Indian camp only three days before probably arrived at Catfish Camp at the same time the murders that he was blamed for, and forever associated with, were committed.

Greathouse and those who had joined his enterprise knew they had little time to spare. Indians most often went on the warpath to avenge real or perceived injury or insult. They repaid murder with murder, regardless of whether those they killed in reprisal were the actual guilty party. Greathouse’s men gathered their families, maybe collected as many head of cattle they might reasonably drive, and loaded what few possessions as would fit on any wagons, carts, or the backs of draft animals they had. Then, in the words of Reverend Zeisberger, the murderers “soon fled and left the [other] poor settlers as victims to the Indians,” as they struck the road toward Catfish Camp and Redstone with their two-month-old captive. Others sought refuge in the more-settled areas as well. According to Baker’s neighbor, James Chambers, “the settlements near the river broke up,” and the inhabitants took the road toward Catfish Camp.44 Zeisberger reported that “many are fled and left all their effects behind.”45

Cresap arrived at Catfish Camp at the head of a party of armed men on Saturday, April 30. The men first carried the wounded Morrison on his litter to the home of Dr. William Wheeler for much-needed medical attention. Thus unburdened, they all “lay some time” and rested at the cabin of William Huston. In the conversations that ensued, Cresap’s followers learned that the news they had killed three Indians on the Ohio near Wheeling and at Pipe Creek had preceded them. When their host inquired about the stories’ veracity, they “acknowledged they had fired first on the Indians” and boasted they had killed some warriors. Cresap’s men believed they had complied with legal orders issued by competent authority and therefore felt no need to defend their actions. After they had rested sufficiently, the men continued “on the path from Wheeling to Redstone,” leaving Morrison in Wheeler’s care.46

On Sunday, the day after the bloody incident, the people “who . . . killed some women and other Indians at Baker’s Bottom” arrived at Catfish Camp. As the members of Cresap’s group had the day prior, some of the party “tarried” at Huston’s. Although they had no wounded, they did have a captive “whose life had been spared by the interference of some more humane than the rest,” according to their host. One of Huston’s neighbors, the widow Martha Jolly, started feeding and dressing the baby, and “Chirping to the little innocent.” Her then-sixteen-year-old son, Henry, remembered the baby smiling at his mother and him. The next morning, when Greathouse and his followers prepared to continue “on their march to the interior parts of the country,” one of their women took the child from Jolly and explained her intent to send the little girl to her “supposed” father, John Gibson. William Crawford arrived at Catfish Camp on his way from Staunton back to Pittsburgh just before Greathouse’s people departed. Being acquainted with Gibson, he took the child into his care and headed toward his Spring Garden home.47

Crawford had spent of much of the early spring surveying land in Augusta County for several clients, including his friend George Washington. The volatile situation and escalating violence caused him difficulty in completing his work on two of Washington’s claims. The delay prevented Crawford from submitting the surveys to Thomas Lewis, the county surveyor, before the latter departed for Williamsburg to file the latest claims on behalf of their owners. The visit nevertheless proved beneficial, and Crawford “was very friendly treated” during his stay. Colonel Charles Lewis, the county lieutenant, administered Crawford the oaths necessary to be sworn by officers of the Virginia militia and presented him with a captain’s commission.48

MEANWHILE AT PITTSBURGH, Captain Commandant Connolly faced a serious crisis on Sunday, the first day of May. As the alarm spread, it became impossible to convince many frontier inhabitants not to abandon their homes. Refugees flooded into town and swelled the population. As panic spread across the countryside, he resolved “to make every provision necessary for the defense that this place and opportunity afforded.” As authorized by the colony’s Militia Law and the Invasions and Insurrections Act, Connolly ordered out the militia companies of Pittsburgh, which totaled about one hundred men. While conducting musters and inspecting the troops, he found many of the townsmen had no weapons. To remedy the situation, he saw it as his duty and within his authority to seize all privately owned firearms and ammunition that could be obtained for military use. With no arms available “but rifle guns intended for Indian trade & of considerable value,” he impressed the weapons and then “appraised & distributed to such men” as he thought proper.49

As Dunmore had noted on his tour of the district in 1773, Fort Pitt needed extensive work to restore it to a state where it could provide a garrison for the militia as well as a shelter for the inhabitants of the surrounding area in an emergency. When Connolly proclaimed Virginia’s sovereignty over Pittsburgh and its dependencies only five months before, the blockhouse, which stood as an outwork, represented the only usable military feature at the post. Since the British army evacuated the garrison and sold the property to a private interest in 1772, the masonry and wooden structures had been largely disassembled, with the bricks and timbers sold as salvage to local inhabitants for building material. With the crisis providing the catalyst, Connolly began the process of making the much-needed repairs and improvements, which the post required to meet the colony’s new military contingencies.

Looking beyond the immediate neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Connolly began to raise troops from the district’s militia to defend the several dependent communities. He issued orders “to draught one third to this place . . . in order to . . . repair this heap of ruins [Fort Pitt] and to impress provisions, horses, tools &tc.”50 Throughout the first week of May, he reported that militiamen under his command attempted to bring inhabitants into the fort and stopped all men capable of bearing arms who attempted to flee and armed them for service. On Wednesday, May 4, he conceded in his journal that “many of them however deserted.” Despite the desertions, Connolly succeeded in amassing a sizeable force and reported that he had every available person employed in “fortifying the fort.” The next day he added, “all the inhabitants of the town at work.” By Friday, they had made enough progress for him to note that the two western bastions were being strengthened with pickets and “ordered teams to haul in all their . . . timber for that purpose.” At the same time, masons repaired the breaches in the angles of the brickwork, while carpenters worked on the gates of the sally ports.51

Reverend John Heckwelder, who later wrote a history of the area Indians based on his observations as a contemporary missionary, explained the protocol followed at an Indian council to prevent war when one nation had insulted or injured another. “If the supposed enemy is peaceably inclined, he will . . . send a deputation to the aggrieved nation, with a suitable apology.” The deputies would tell the leaders of the injured party that the act they complained about had been committed without their chief’s knowledge by some of their “foolish young men.” After describing that the offending actions were “altogether unauthorized and unwarranted,” the offender’s nation offered suitable apologies and condolence presents to cover the dead.52

On Thursday, Croghan and McKee, with Connolly and others in attendance, met at Croghan Hall with Indian leaders, including Guyasuta, the deputy for the Six Nations, and the chiefs of several Iroquois and Delaware bands. Following the established protocol of Indian diplomacy, they opened with a “Condolence” for the Six Nations, Shawnees, and Delawares “on the late unhappy death” of some of their friends. In an effort to “wipe the tears” from their eyes and symbolically bury the bones of the dead by covering them with gifts, the colonial representatives distributed presents and strings of wampum to each nation on behalf of their people. The current and retired Indian Department deputy superintendents then requested the assembled chiefs to use their influence with the “distant chiefs” to prevent war between their peoples. Each Indian leader in his turn spoke in a “most friendly and reasonable manner” and pledged to honor their treaty obligations and remain loyal to their British allies.53

Knowing the importance of diplomacy as well as military preparedness for security on the frontier, Guyasuta gave a speech that assured the colonial officials of the Iroquois Confederacy’s determination to “take no part with the Shawanese” and the certainty the Delawares would do likewise. Going further, Guyasuta said that the Six Nations and Delawares would “never quarrel with their Brethren the English,” but would “live & die” with them in a fight against the Shawnees. He further recommended that Lord Dunmore build a fort on the Ohio at the mouth of the Great Kanawha to keep the Shawnees “in awe” and prevent their war parties “from makeing Inroads amongst the Inhabitants” of Virginia from the Ohio River to “Redstone and Everywhere.” He believed that people living there, although exposed to depredations, should plant their crops and be guarded by some of the militia until the Shawnee made their intentions known. It was no secret that the Shawnees had displeased the Iroquois Confederacy and its dependent nations. Guyasuta assured British officials at Pittsburgh that an attempt to cause any “Mischief” by the Shawnees would result in their being resented for it by the Delawares. He added that their conduct over the previous twelve months made it clear that no other nations would join them in a war against British interests. If the Shawnees rejected the message calling for them to remain peaceful and did “not listen to Reason,” Guyasuta believed “they ought to be chastised,” or punished.54

The Crown and Virginia officials and Guyasuta agreed to join in sending the Shawnees one message, carried by two respected Delaware chiefs, to articulate the British position. They also decided to share its contents with the assembled tribal representatives as well as any others who could make it to Croghan Hall. Simon Girty, the Indian Department’s interpreter, delivered the message and invitation to Koquethagechton, or Captain White Eyes, and Konieschquanoheel, also known as Hopocan, or Captain Pipe, to meet with the English, and escorted them to Pittsburgh on his return trip.55 Having tirelessly sought to resolve disputes between Indians and whites in the past, White Eyes was regarded by many as the most influential Delaware chief in the Ohio country. Pipe enjoyed a reputation in which his influence among the Delawares and his friendship with the English were equal to those of White Eyes.

Connolly wanted the Delaware chiefs, “to hear what we had to say on the differences which had arisen between us [the Virginians] and them [the Shawnees].”56 While he busied himself managing the myriad tasks involved with defending the district and making Fort Pitt a respectable defensive installation again, another Indian chief arrived. Connolly presented him with a string of wampum and a speech that expressed a desire to remain at peace. The militia commander also wrote two announcements to be printed on broadsides as well as read and posted throughout the district. One informed the people that the situation appeared to give reason to apprehend “immediate danger from the Indians and particularly the Shawanese.” Heeding Guyasuta’s advice, the other ordered all traders to refrain from importing liquor into Indian country and reminded them that Virginia law strictly prohibited conducting any trade with an enemy, with the promise that anyone caught conveying liquor to “suspected enemies” would “answer . . . at their peril.”

Amid all the bustling activity, the Indian council reconvened on Friday, May 6. Connolly observed as Croghan and McKee conducted the conference, with Guyasuta and some other Six Nations chiefs, and Pipe, White Eyes, and other Delaware leaders attending. The Indian Department men, as the protocol of Indian diplomacy required, distributed presents to the chiefs in condolence for the Delawares that had lately been killed on the river. The Indians, according to Croghan, spoke in a “most friendly and reasonable manner” while discussing the recent violence. All repeated their promises to continue adhering to their professions of peace. As a representative of the Virginia colonial government, Connolly delivered the speech and distributed copies that the chiefs could carry for the interpreters to read to their people on the north bank.

After expressing his sorrow at the disputes and resultant events, which had bad consequences for both parties, Connolly assured the Indian representatives that Virginia officials “had no act or part” in what happened and that he had certainly not issued orders to kill any Indians without cause. He laid the blame entirely on “the folly and indiscretion of our young people,” who, like their own young men, were “unwilling to listen to good advice.” Connolly promised to investigate and determine exactly what had happened. He hoped the dispute could remain limited to the “young and foolish people” of both sides without engaging our “wise men” in a quarrel in which none of them had a part. He told the Indian leaders that the incidents could not have happened at a worse time, since “the Great Head Man of Virginia,” Lord Dunmore, and “all his wise people”—meaning the General Assembly—were about to meet in their own council to discuss settling the country bought from the Six Nations. The captain commandant assured the chiefs that Virginia settlers would “come to be your neighbors . . . [and] to be kind and friendly towards you.” He further expected that “they will buy goods to cloath your old people and children to brighten the chain of friendship” between them.

The officer pledged that the Indians would find Virginians as friendly toward them as their “late neighbors” from Pennsylvania. He concluded by asking them “not to listen to what some lying people that may tell you to the contrary”—that although Virginians were always ready to fight an enemy, they would show their “true & steady friendship” on every occasion when warranted. After asking Pipe and White Eyes to carry his words home to their people and the Shawnees, he reassured them he would do all in his power to bring those guilty of committing the murders at Baker’s Bottom to justice and invited them to a general peace conference at Pittsburgh. The council adjourned on May 6, and the Indian leaders headed home.

Connolly maintained the stated position that the matters in dispute between the Indian nations and the colony could still be resolved amicably, notwithstanding the “violent and barbarous treatment” many native people suffered at the hands of “unthinking and lawless people.” When notified that thirty armed men, not embodied as militia, had gone down the Ohio in pursuit of Indians, he took quick action to officially disapprove of their actions and prevent a tragedy. Knowing that White Eyes’ family and other peaceful Indians lived just across the river from Pittsburgh, Connolly sent the sheriff and a small unit of militia to compel the thirty disorderly white people to return to Pittsburgh. He also sent an interpreter to locate White Eyes’ family and escort them to the Croghan Hall plantation, where they could remain under the colony’s protection until the chief returned from his diplomatic mission to the Shawnees. In order to forbid individuals from taking unauthorized action again, Connolly posted advertisements reading that any “attempt to behave so contrary to peace and good order of this country” would be punished by all means available within his power as a magistrate and military commander.

To facilitate the safe assembly of the various Indian chiefs at the next council, Connolly published yet another public notice. He informed the inhabitants of West Augusta that they would join him in welcoming some of the most influential chiefs of the Ohio area nations. “In His Majesty’s Name,” he commanded all British “subjects of the colony and Dominion” of Virginia to “desist from further acts of Hostility against any Indians whatever, especially those expected to come to the fort for “business in their usual manner.” Connolly sent twenty bushels of corn to feed the Indians assembled at Colonel Croghan’s.

The same day, Connolly held a conference with some “country people” who had retired to a place about twelve miles south of Pittsburgh, where they requested permission to build a stockade fort for their own protection. The captain cautioned them that their stockade would only afford them “imaginary safety” at best. Dividing the available strength of the country’s militia, he explained, might make them feel more secure in their separate communities, but it actually tended to only “lull people into supineness and neglect” and render their defenses ineffective in opposing the enemy. In consequence, they would ultimately be forced to choose between either having to abandon the country or “fall sacrifices to the vindictive rage of the savages.” If the refugees still thought that Pittsburgh was too crowded with women and children, he at least wanted their presence to benefit his plan of defense. Connolly agreed to permit them to build a fort upriver on the Monongahela as an intermediate post to keep the line of water communication open with the Redstone settlement. In return, they would have to send one-third of their active young men to assist in repairing and defending Fort Pitt, which, if taken by the enemy, would certainly result in the whole country west of the Allegheny being abandoned. Although they said they agreed at the meeting, Connolly did not expect them to actually comply with his request.

Back in Indian country, the Moravian missionaries at Schönbrunn had finally learned that the Virginians had officially taken control of Pittsburgh and the surrounding country on April 30. That and other news prompted Reverend Zeisberger to note in his journal that he believed the Virginians feared that the Shawnees had begun preparations for war against them. The runners also informed the missionaries about the recent Indian council at Croghan Hall, during which Guyasuta relayed William Johnson’s warning to other Ohio Indians not to join the Shawnees in attacking whites on the south bank. By the end of the first week in May, several Munsee Delawares arrived to inform the missionaries and their congregation that one Shawnee chief had been killed and another wounded on the Ohio—a reference to the skirmish at Pipe Creek. Zeisberger lamented, “It seems Indian war will break out,” and feared the Virginians would attack and destroy Shawnee towns.57 While the clergymen prayed that both sides would resolve their differences without war, worse news followed. An express from nearby Gekelemuckepuck brought the news of the murders of nine Yellow Creek Mingoes and attributed them, as well as the other recent killings, to Cresap.58

Gekelemuckepuck sat on the north bank of the Tuscarawas River, a tributary of the Muskingum. Zeisberger described it as a thriving community having more than one hundred log houses in 1770. As the principal town of the region’s Unami Delaware, it also served as a political capital for the Lenape people living in the Ohio country. As the home of Netawatwes, a respected Turtle clan Delaware chief whom the English called Newcomer, most whites therefore knew Gekelemuckepuck as Newcomer’s Town.59

In the aftermath of the massacre, the Mingoes evacuated their camp on Yellow Creek and headed toward Gekelemuckepuck. As members of the injured community arrived, they told their hosts, and anyone else present, of the treachery of the Big Knife and their barbarity to even those who are their friends. Although none of them got close enough to see firsthand, they all alleged that Cresap had not only led the murderers at Baker’s Bottom but attributed all of Daniel Greathouse’s actual as well as the contrived actions to him.60 Throughout Indian country, as they had in white communities, facts became intertwined with fiction with each retelling so that the tragedy sounded even more horrifying. By the time William Johnson received it, the report stated that “a certain Mr. Cressop, an inhabitant of Virginia,” was responsible, and that he had murdered “forty Indians in Ohio.”61 Even the Pennsylvania partisan Arthur St. Clair stated in a letter to Governor Penn his belief that, “The mischief done by Cressap and Great House had been much exaggerated.” Before long, messengers reached the Delaware towns and Moravian communities telling that the Virginians had attacked the Mingo settlement on the Ohio and butchered even the women and the children in their arms, and that Logan’s family were among the many slain.62

As soon as the aggrieved Mingoes settled in at Newcomer’s Town, they began hunting, but not for game. Zeisberger learned they were out “to catch some traders” traveling between towns in order to kill whites—any whites. Many Shawnees, a number of whom already held some animosity toward the Virginians, joined the Mingoes in the endeavor. These hunting parties took no time to determine whether their prey were Virginian or Pennsylvanian. Whoever saw a white man saw an enemy. Seeking allies, the Mingoes sent runners to the towns at Wakatomica on the Muskingum, inviting the Shawnees and Delawares to join them for a council of war at Newcomer’s Town.63

The Delawares, being more peaceful, kept all traders from using the roads for their protection.64 Knowing that the Mingoes were likely to take revenge on any white people prompted the Moravian missionaries to “shut themselves up” in their communities. Heckewelder wrote that the friends and relatives of those murdered at Yellow Creek “passed and re-passed through the villages of the quiet Delaware towns, in search of white people.” As soon as they became aware of what they were doing, Mingoes also aimed their anger and the most abusive language imaginable at the Delawares who shielded the white devils from their vengeance.65 The situation caused the white Moravians such great distress that they did not know what action to take. “Our Indians,” Heckewelder said, “keep watch about us every night, and will not let us go out of town, even not into our corn fields.”66

Trying to maintain calm, some of the more moderate Shawnee chiefs sent a message asking “their grandfather, the Delaware nation,” to remain peaceful, “easy and quiet.” The headmen encouraged all Ohio Indians not to molest or hurt the traders or any other white people in that quarter and the women to continue their spring planting until they determined what would happen. Zeisberger concluded that the Shawnee chiefs desired “to keep the road to Pittsburgh clear, and not hurt the Pennsylvanians,” as the source of diplomatic contact and the trade goods on which they depended, as well as firearms and ammunition, but to only contend with the Virginians as potential enemies.67

Many on both sides of the Ohio expressed their concern for the safety of traders in Indian country, a number of those finding themselves hunted by people with whom they had usually conducted business. At the end of the first week of May, one trader who made it to Pittsburgh from Newcomer’s Town related that a Delaware headman had warned him to flee following the arrival of a wounded Shawnee warrior. The injured man reported that hostilities had commenced, and the English had killed several of his people. Because he expected a Shawnee war party to arrive and threaten his life and those of the Delawares who would try to shelter him, the white man departed in such haste that he left all his property behind him. Many like him, however, still remained.68

Meanwhile, the four men Captain Russell had sent out to reconnoiter returned to Castle’s Woods on the Friday of the first week of May. They had, according to the captain, “faithfully performed the Service, both as Scouts, and in regard to the boundary Line.” After they made their report under oath before a justice of the peace, Russell sent a written copy to Colonel Preston for him to convey to Williamsburg and the General Assembly. The report left no room for any doubt that the Louisa River defined the border between Virginia and the Cherokees. Arriving when it did, the report also helped to determine the legality of any claims still in dispute and afforded the claimants the time and opportunity to adjust their entries at the extraordinary surveyors’ expense. Furthermore, having it in possession enabled the General Assembly to appropriate the necessary funds to pay the scouts for their service without making them suffer a lengthy delay.69

When William Crawford returned home with his new ward, Koonay and John Gibson’s daughter, he sent George Washington copies of the surveys for his Augusta County property and a letter acquainting him with the “truth of matters” on the frontier. Despite having some remaining doubts, Crawford gave Washington the most accurate account possible, from his perspective, on the recent violence. Anticipating retaliation for the massacre of the Yellow Creek Mingoes, he wrote, “Our inhabitants are much alarmed, many hundreds having gone over the mountain, and the whole country evacuated as far as the Monongahela; and many on this side of the river are gone over the mountain.” With his new Virginia militia commission, he had mustered one hundred men whom he planned to lead to Fort Pitt, and combined with those posted at Wheeling, “shall wait the motions of the Indians” and act accordingly. Although an Indian council had convened to avert war, he confessed, “What will be the event I do not know,” and concluded, “In short, a war is every moment expected.”70