CHAPTER 4

Trained in Martial Exercise

Escalating Violence and the Militia Law

May 1774

PUSHING HIMSELF to exhaustion, Captain Commandant John Connolly continued his efforts to rehabilitate Fort Pitt, prepare the local militia for action, prevent the flight of fearful inhabitants, and maintain civil order. On Saturday, May 7, 1774, with the authority vested in him by Governor Dunmore’s orders appointing him as the district’s commanding officer, he started offering militia commissions to reliable people who would recruit volunteers for active service, preferably men without families, and march them to the fort “to enter in the pay of government.” That day, he presented an ensign’s commission to a man who brought eighteen volunteers to Pittsburgh. Captains William Crawford and John Neville visited the post and recommended that if Connolly issued them “Blank Warrants” to appoint subordinate officers they “would ride about the country and use their utmost endeavors to encourage young men to enter into the service.”1

Two days later, courtesy of Neville, twenty-four militiamen from Peters Creek arrived to reinforce the garrison, along with “four Negro men . . . with proper working implements” to help repair the defenses. Connolly remarked that Neville’s action had rendered “infinite service to me and the country in general,” and hoped it would inspire others to exert themselves during that critical time. On Tuesday, Crawford led a welcome reinforcement of about one hundred men into Pittsburgh and expected to meet others there and at Wheeling, where they would wait to see what the enemy would do and take appropriate action. The added strength allowed Connolly to send a forty-man detachment under Captain John Stephenson, Crawford’s half-brother, to protect frontier settlements and prevent any small Indian war parties from attempting to “disturb the tranquility” of the inhabitants, although their chiefs tried to restrain them and remain peaceful.2

Amid all the activity and confusion, Connolly heard, and possibly believed, some of the distorted second-hand accounts of Cresap’s alleged culpability in the massacre of the Yellow Creek Mingoes. Although many frontier inhabitants had already suffered from the retaliatory raids against their neighbors, it astonished Connolly that they viewed the men who provoked them as meritorious.3 As if he did not face enough challenges, some obstinate people from the frontiers of Pennsylvania arrived on Wednesday, May 11, behaving in a very disorderly and riotous manner, and threatened to kill the Indians staying at Croghan’s nearby plantation. After the captain commandant had the leaders confined, their followers threatened to break them out of jail. In response, Connolly doubled the guard and ordered the officers to fire on any of the armed militia who mutinied and attempted to rescue the prisoners. He also took the precaution of posting two guards and his interpreter at Croghan’s home in the event the troublemakers appeared there. By Thursday, the mutineers had apparently come to what Connolly described as a better sense of how they could serve their country, and he dismissed them after they, or someone on their behalf, posted a bond as security for their good behavior.4

By week’s end, provisions began to arrive at Fort Pitt from the surrounding communities with more regularity, which helped to ease the sense of crisis somewhat, until Connolly received more alarming news. A large body of armed men—not embodied as militia—had gathered at Catfish Camp intent on attacking Shawnee towns in retribution for recent Indian incursions. Unaware that Michael Cresap had called them together, Connolly wrote the men a letter requesting—and ordering—them to return home. He also alerted Captain Stephenson and ordered him to use his company to dissuade any disorderly people from committing any acts of violence against Indians “without the countenance of government.”5

Connolly needed no more such problems when, on May 19, an Onondaga Indian delivered an insolent message from Daniel Greathouse, Joseph Swearingen, Nathaniel Tomlinson, Joshua Baker, J. Brown, and Gavin Watkins. After identifying themselves as the six people who had killed the Mingoes opposite Yellow Creek, they demanded that Connolly order the Indians to remain on their own side of the river or they would kill more of them. The district commandant dispatched an officer and six men to find and present the ruffians with his reply. He rebuked them for their demands and condemned them for committing barbarous and evil actions for which they deserved the severest punishment the government he represented could impose. After sarcastically observing they had not also murdered their messenger for being an Indian, he concluded with an admonition that if he ever heard that they had either attempted to kill or killed any friendly or unoffending Indians, he would order a party of militia to apprehend them, as well as all those who aided and abetted them, and bring them to justice for “exemplary punishment.”6

The same day, Connolly alerted commanders of the different corps of militia in the country that recent intelligence warranted a heightened state of readiness. In accordance with the Militia Act, he ordered each captain to immediately call a muster of all the militia in his neighborhood to inspect and examine their arms and accoutrements, and equip those deficient in the best manner possible. Issuing warrants, he authorized militia commanders to impress all necessary provisions, salt, entrenching tools, and other items they needed to perform their duties in accordance with the law for opposing invasions and insurrections. After accomplishing these tasks, he ordered them to detach one-third of their respective companies under the command of their lieutenants and send them with the impressed items to his immediate assistance. Keeping the rest of their men under arms for the defense of their communities until they received further orders, Connolly directed his subordinates to take the necessary measures to stop any people fleeing the district and escort them to Pittsburgh with their belongings. Finally, he cautioned that it may prove necessary to send detachments to assist neighboring communities, or concentrate all their forces at Fort Pitt if hostile Indians wanted that town “to feel the first effects of their resentment.”7

Such language appeared to contradict Connolly’s public insistence that negotiations could settle the disputes without further bloodshed. On May 20, he received a reply from the “disorderly people” at Catfish Camp in which Enoch Innis and Michael Cresap explained that they had assembled in response to recent Indian attacks and challenged Connolly’s assurances of peaceful accommodation. If he was so certain that diplomacy would prevent war, the spokesmen invited Connolly, Croghan, and McKee to meet them at Catfish Camp on Monday, May 30, to provide “surety”—essentially agreeing to become hostages—against any Indian depredations for the next six months. Otherwise, the armed band would unilaterally attack the Shawnees. Connolly replied with what he described as a “friendly” letter requesting Cresap to discharge the people he had imprudently assembled without any authority because their presence threatened to render all efforts to prevent conflict meaningless. After waiting two days, Connolly instructed Captain Paul Froman to assemble his militia company, properly armed and equipped, to wait for orders at Redstone. If by noon on Wednesday, May 25, Connolly learned that Cresap and his associates had listened to reason and dispersed, he would order Froman to dismiss the men. Otherwise, Froman’s company would march to Catfish Camp and force those gathered “to desist from their destructive scheme.”8

WHITE EYES arrived at Schönbrunn three days after leaving Pittsburgh on his mission toward the Muskingum to seek an accommodation of concerns with the Shawnees. At McKee’s suggestion, two Pennsylvania traders, John Anderson (or Saunderson) and David Duncan, accompanied him as “public messengers” to deliver the appeal for the Shawnees to desist from all hostilities. Concerned for their safety, Zeisberger warned that Indian country had become very dangerous for white people—even those accompanying a respected Delaware chief. Failing to deter the three, the missionary cautioned them to avoid the more heavily traveled road.9

On reaching Newcomer’s Town, the three men noticed the number of traders who had taken refuge there. The town’s headmen also warned them of the perils and advised that only one messenger should continue to Wakatomica with White Eyes while the other waited with them. Following a brief discussion, Anderson accepted the invitation to stay. The others had barely departed the town when an angry musket shot narrowly missed Duncan. White Eyes shouted for the trader to hurry back to the shelter of the village. The chief then “got betwixt” his companion and the assailant, a Shawnee warrior, and disarmed him as he attempted to reload his musket. On his return, the chief personally made the town’s Delaware inhabitants responsible for his messengers’ safety. The friendly Indians immediately locked all the traders in a “strong house” and had a guard kept on them day and night to protect them from any attempt that might be made on their safety by the Shawnees or Mingoes. Their hosts brought them provisions and anything else they might need to be as comfortable as possible.10

Hokoleskwa, the chief whose name translated to Cornstalk—also known to Indians by a name translated as Hard Man—and the other Shawnee headmen politely received White Eyes. They sat around the council fire and listened to the words of apology and condolence for the recently killed Shawnees and the messages delivered on behalf of the colonial commissioners at Pittsburgh. After White Eyes had finished, Cornstalk rose to his feet and responded. He expressed regret that people on both sides had suffered “much ill.” The Shawnee held the Virginians responsible for the series of warlike incidents, “All which Mischiefs so close to each other Aggrevated our People very much.” As a remedy, Cornstalk demanded that Governors Dunmore and Penn exert their authority more forcefully over the backcountry settlers to stop such aggressive actions in the future. He specifically urged that Connolly, as Dunmore’s surrogate in the area where most of the violence occurred, “endeavor to stop such foolish [white] People,” as Cornstalk had with great pain and trouble prevailed on the Shawnees “to sit still” and refrain from violence until their headmen settled the disputes.11

The gathering war clouds had deterred many young Shawnee men from going on the spring hunt. Cornstalk offered to have his nation’s warriors escort groups of traders to protect them from the vengeance of friends and relatives of the recently slain who might be waiting along the road to attack them as they traveled home. At the end of the meeting, Cornstalk addressed White Eyes as his “brother” and charged him to deliver his reply to Croghan, McKee, and Connolly, and entrusted him with the string of wampum to testify as the Indians’ documentary record, as well as a mnemonic aid for translating the speech.12

Pipe joined White Eyes when the grand council convened at Newcomer’s Town on Sunday, May 15. Although the envoys urged the leaders representing the Ohio-area Indians to maintain peace, a group of twenty boisterous Mingoes kept “stirring up the Shawnees.” Despite the interruptions, Pipe and White Eyes assured those assembled in council that the gang of lawless villains responsible for the recent murders had not acted on Dunmore’s orders. While most Delawares seemed amenable, no argument assuaged the anger of the Mingoes and an increasing numbers of Shawnees. When they threatened to kill all white people they met, the town’s residents only became even more protective of those they harbored, and determined not to allow the hostiles to take them by surprise.13

A few days later, runners brought news from Pittsburgh and a message from Croghan. The retired but still influential deputy Indian superintendent advised all Ohio Indians to “be quiet, and not think of war,” and prevent any harm to the traders while Virginia authorities did their utmost to apprehend and bring their peoples’ murderers to justice. Croghan added that authorities had already taken one of the villains into custody. After the council had concluded, runners delivered the “agreeable news” to Heckewelder that the Shawnees had decided to remain at peace.14 No sooner had this raised his hopes than conflicting rumors that the Shawnees had declared war dashed them again.

At places like the Mingo enclave near Gekelemuckepuck and the Upper Shawnee towns of Wakatomika, inhabitants heard the drums beating as groups of young men, eager for martial glory, gathered in front of council houses. They listened to Logan and other captains call on those willing to follow to join them on the warpath to avenge the recent murders of their people at Yellow Creek and on the Ohio. As onlookers watched, the warriors participated in a spectacle, as described in James Smith’s captivity narrative, that combined military drill, religious ceremony, and social gathering. Those who had already committed to the enterprise formed into lines and began moving in concert with the beating of the drum, not altogether unlike European soldiers on parade. The braves advanced across the open space to a certain point, and then halted. In unison they gave what one white observer described as a “hideous shout or yell” and stretched their weapons menacingly in the direction of the enemy’s homeland, then “wheeled quick about” and danced back in the direction from which they came. After they all returned to the starting point, the leading warrior sang his war song and moved to the painted war post, where he declared his reasons for going to war. After he boasted of his exploits in past battles, he affirmed what he intended to do to any enemies encountered in the next one and struck the post with his tomahawk to demonstrate.

As comrades and spectators applauded in approval and shouted encouragement, the next warrior advanced to the post and repeated the ritual. Whether they sought adulation for performing bravely in battle or just wished to not be left behind by their peers, other young men took up the hatchet as the members of the war party cheered and welcomed them. The ceremony concluded after the last man struck the post. The next morning, warriors bade farewell to friends and loved ones and marched to battle. The news spread quickly through Indian country. Shawnee and Mingo warriors, as well as those of other nations who volunteered to join them—even though their tribal councils decided to remain neutral—repeated the scene in numerous towns north of the Ohio in the months that followed.15

Shortly afterward, a group of mission Indians told Heckewelder that while visiting Mochwesung they had witnessed Munsees perform a similar war dance after a party of Mingoes paraded a white man’s scalp through the town.16 Zeisberger’s prayers that “the dark cloud” of war would soon pass over and peace be restored went unanswered as he learned that the Shawnees had only agreed to remain peaceful at the council to mollify the Delaware faction. Newcomer arrived at Schönbrunn and broke the news that Shawnee and Mingo leaders had met in a separate council at Wakatomica. Although he had addressed them in a fatherly manner about the “blessings of Peace and Folly of War,” the Delaware chief told them the Shawnees and Mingoes had decided to fight. According to Newcomer, Logan had announced that he sought immediate vengeance for the murders of his relatives and took the warpath with nineteen followers to kill the traders who were pressing their peltry at the Canoe Bottom on Hockhocking Creek and make an incursion against Virginia settlements opposite the mouth of Yellow Creek. Newcomer then asked several mission Indians to run ahead to inform Killbuck, who had passed through while escorting a group of fleeing traders toward Pittsburgh.17

The missionaries pondered how their flock would meet the crisis. An invasion of the Ohio country would present the greatest threat, according to Zeisberger, as it put their community in danger from both sides. He feared that the conflict might escalate into a general Indian war in which the Pennsylvanians joined the Virginians and possibly targeted the Delawares as well as the Shawnees and Mingoes. Should the community’s white brethren feel compelled to flee, Zeisberger believed most of the converted Indians would follow them eastward and reestablish the towns they had abandoned on the Susquehanna. Such a migration involved great risk, and he questioned their ability to gather and carry sufficient quantities of provisions to sustain their entire population while on the move. The missionaries and leaders of the praying Indians joined the headmen of neighboring towns in appealing to Newcomer to assist them in the good work of preserving peace. Although it seemed time would run out, the venerable chief urged all Indians “not to stop the road to Philadelphia, but to let it be free and open” by maintaining friendly relations and trade with the Pennsylvanians.18

WHITE EYES returned from his embassy on Tuesday, May 24, and met with Connolly, Croghan, and McKee to inform them of the results of his mission and deliver a letter from Duncan and Anderson. The two men wrote that they and nine other traders, including one George Wilson, had left their shelter at Newcomer’s Town and headed toward Pittsburgh with an escort of armed Delawares. Meanwhile, the suspense of waiting at Ligonier proved too much for St. Clair to endure, so he decided to risk the consequences of an encounter with Connolly. His gamble paid off when Pipe and White Eyes returned the very day he arrived.19

The same day, Connolly received the news that Cresap had disbanded his men and sent them home. Relieved, he dispatched expresses to inform Froman and the other captains that the danger had passed, and ordered them to dismiss their men with his thanks. A few weeks after he returned home from Catfish Camp, Michael Cresap received a commission in the rank of captain in the Hampshire County militia, signed by Lord Dunmore on June 10. He and Connolly extinguished any personal resentment each held against the other as a result of the accusations that followed the massacre of the Mingoes from Yellow Creek. The two men now had to work together for the good of their adopted country of Virginia.20

The relief Connolly experienced when he learned the situation with Cresap had been diffused was quickly replaced with another source of tension that evening. As Croghan and McKee prepared for the next day’s council, Connolly received intelligence that some Indians had fired on laborers working in some fields down on the Old Pennsylvania Road just outside of Pittsburgh. A man working in one field had suffered a chest wound, while three laborers last seen in an adjoining field were reported missing and presumed taken captive. Connolly dispatched Captain Abraham Teagarten with fifteen soldiers to investigate and reconnoiter the area for tracks or other signs that indicated the presence of marauding Indians.21

On Wednesday afternoon, White Eyes delivered messages from the Delawares at Newcomer’s Town as well as Cornstalk’s reply on behalf of the Shawnees to an assembly that included McKee, Connolly, several Delaware sachems, Guyasuta, the official deputy, plus eight other chiefs from the Iroquois Confederacy, and St. Clair, who represented Pennsylvania at Croghan’s suggestion. Listening intently, no one doubted the Delawares’ sincere desire to remain at peace. However, the “most insolent nature” of the Shawnees’ reply stunned Connolly. Speaking through White Eyes, Cornstalk condemned as lies all that Croghan, McKee, and Connolly told the Shawnees. In consequence, the Hard Man admitted that twenty warriors had gone out to get revenge for the recent deaths of their people at the same time he acknowledged the Virginians’ attempt to accommodate their complaints. Cornstalk further infuriated Connolly when he answered the captain’s request that the Shawnees “not take amiss the Act of a few desperate young men” by declaring that Virginians should therefore likewise “not be displeased at what our Young Men are now doing, or shall do against your People.” Furthermore, the chief ridiculed the Virginians for building forts on their side of the Ohio, and made it clear that the Shawnees would only talk peace with Governor Dunmore after they “got satisfaction,” or exacted revenge by killing some white people, “but not before.” Shawnee warriors, he said, were “all upon their Feet” ready for war. St. Clair also characterized Cornstalk’s reply as “insolent” but believed the Shawnees meant no harm toward Pennsylvania and wrote Penn that they “lay all to the charge of the big Knife, as they call the Virginians.”22

St. Clair then stood and addressed the assembled Iroquois Six Nations and Delaware representatives on behalf of Governor Penn and thanked them for their good speeches promoting peace. Pennsylvanians, he said, remained determined to maintain the friendship that existed between the Six Nations and Delawares and them. However, since the threatening actions of the Shawnees had alarmed Pennsylvanians, he urged the chiefs to prevent their people from hunting on the south side of the Ohio because some settlers will not be able to distinguish between them and those who may be enemies. St. Clair pledged that his colony’s government would endeavor to keep the “Path” of communications and commerce open and “keep bright the chain of Friendship so long held fast by their and our Forefathers.”23

As the Indian council convened at Fort Pitt, Anderson, Duncan, and company arrived with their nine Delaware escorts. Anderson and Wilson admitted that it took some hard work to get back. The latter added that the Delawares, who still seemed friendly at that time, had enough to do to save their lives from hostile Shawnees and Mingoes. Duncan praised the people of Newcomer’s Town for treating them with a great deal of kindness and demonstrated nothing but peace and friendship from all their actions. Wilson remarked that while he had escaped with his life, he had to leave about fifty horseloads of deer skins in the Lower Shawnee Towns. More ominously, the three traders confirmed that before they departed, Logan had set off with about twenty Mingoes and other warriors to strike Virginia settlements near Wheeling. They also worried that hostile Shawnees or Mingoes had gathered for the purpose of finding and killing their fellow traders still in Indian country. Wilson added that no one could tell whether they were dead or alive at that time.24 About a week later, two messengers from Newcomer’s Town reported the Shawnee towns had become quiet again. They said a white man named Connor living at Snake’s Town on the Muskingum told them that some moderate Shawnees had taken great pains, together with a group of Delawares, to escort twenty-five or thirty traders, along with their pelts, up the Ohio to Pittsburgh.25

While Croghan disagreed, Anderson feared a frontier war would soon erupt. Rumors ran rampant as settlers reported sighting parties of hostile Indians everywhere, although many proved unfounded. Connolly received messages of new depredations almost daily, such as the incident that resulted in one wounded and three men reported missing on May 24, but he could not dismiss any of them without investigation. After three days, Captain Teagarten’s patrol returned with the three alleged missing laborers in custody after finding no evidence that they had been attacked by Indians. He determined that they had shot and wounded the other man during a heated dispute over land he was improving and only blamed it on Indians.

The same day, a friendly Indian brought Connolly a letter from “an unfortunate trader in the woods” hiding under the protection of one of the interpreter John Montour’s sons. The letter informed the captain that hostile Mingoes had killed and scalped some white people not far from where he took shelter. The stranded man added that some warriors had waited in ambush on the Traders’ Path for two days, intent on killing any whites who approached or left Newcomer’s Town. The trader believed the warriors had crossed the Ohio to attack the homestead of “some distressed family” to assuage their disappointment at the lack of prey on the north bank.26

Reacting to the recent intelligence, Connolly sent Captain Henry Hoagland’s company to Wheeling on Thursday, May 26. Hoagland had orders to intercept any Indians he discovered on “our side of the river” and treat any he encountered who were armed, or whose tracks led toward the settlements, as enemies. Erring on the side of caution, Connolly also ordered Ensign Richard Johnston and Sergeant George Cox to follow with reinforcements.27 The next day, he ordered Captain Joel Reece to immediately march with all the men he could raise and “join any of the companies already out under the pay of the government” to search for, interdict, attack, and pursue any war parties that endangered the frontier communities. Never missing an opportunity to criticize him or the Virginians, St. Clair told Penn that Connolly had sent the troops with orders to fall on every Indian they met, regardless of whether friend or foe. Undeterred, Connolly was constantly improving Fort Pitt’s defenses as refugees fled to its protection from the western-most settlements. Under the provisions of the Invasions and Insurrections Act, he ordered “some indifferent cabins” appraised and demolished in order to use the salvaged wood as pickets for the fort.28

The news that the “Shawanese were for war” spread quickly from the frontier to Williamsburg and Philadelphia. The traders who returned from Indian country informed militia officers with intelligence that as many as forty enemy warriors—twenty Shawnees and twenty Mingoes—had crossed the Ohio intent on striking somewhere in Virginia. One witness found it “lamentable” that “multitudes of poor people” fled the country to seek refuge in less vulnerable areas while others resolved to stay and defend their homes. Neighbors built and manned stockades and blockhouses in which they could better withstand the expected onslaught.29 Valentine Crawford commented that erecting such private defenses, such as his own Crawford’s fort, provided “a very great means for the people standing their ground.” Some who fled from the exposed farms took refuge at these fortified homes instead of heading for the safer areas of the colony and added their numbers to the local militia. Similarly, men who had come to the area to work, such as the hired carpenters and servants George Washington had sent to erect a mill on the bottomland he had acquired near the Little Kanawha River, suspended their projects and volunteered for active militia service and helped the inhabitants build fortifications.30

By themselves, the private forts only provided residents a place of refuge unless area militia posted garrisons in them to take an active role in defending their communities. Arthur Trader recalled that in his “15th or 16th year of age,” after several captains called their West Augusta District companies to muster, he served in a ranging detachment of fifteen to twenty men from the company commanded by Captain Zackquill Morgan. Posted at the fortified home of fellow company member Sergeant Jacob Prickett, the rangers traversed the country between the Ohio and Monongahela Rivers on patrols that frequently provided the frontier settlers timely warning of approaching danger. Trader said he “remained in this service for four months,” during which time his unit engaged in operations “scouting and guarding the settlement against invasion by the Indians.”31

Although St. Clair maintained that the Shawnees had nothing against the Pennsylvanians, many of that colony’s inhabitants from as far away as Bedford took the precaution of forting themselves. Although they had heard of the Delawares’ pledge to remain peaceful, many backcountry inhabitants in both colonies expected that nation’s warriors to strike before long as well.32 Calling the reports from the frontier alarming enough, St. Clair informed Governor Penn that the actual incidents of violence had yet to become “equal to the Panic” that had “seized the Country.”33 Events eventually proved St. Clair wrong.

The summary killing of nonoffending Indians in reaction to depredations committed by hostile warriors was not a crime only Virginians committed. At the end of May, St. Clair informed Penn and Connolly that some disorderly Pennsylvania people had brutally murdered a peaceful Delaware Indian named Joseph Wipey and concealed his body under some stones at the bottom of a small stream. According to the Westmoreland County magistrate, Wipey had lived peaceably in the Ligonier area for a long time and had always been on friendly terms with his neighbors. St. Clair suspected John Hinkson, a man he described as “actuated by the most savage cruelty,” of the heinous crime. He also alleged that Hinkson had incited James Cooper and others with some kind of religious enthusiasm to join him in the murder. Before the coroner had completed his inquiry, however, Wipey’s remains mysteriously disappeared at the hands of some unknown accomplices. Because of a lack of sufficient evidence to make an arrest, Hinkson and Cooper remained at large.34

After the chiefs had returned home from Fort Pitt, McKee had time to review the records of the latest council in an effort to determine whether the two sides faced a further rupture or possible accommodation. He confided to William Johnson that while most Ohio area Indians acted with moderation, the situation remained critical as the tenuous peace ensued. McKee believed some “wise interposition of Government” was necessary for the restoration of a more lasting peace but knew that Generals Gage and Haldimand had focused their attention on Boston. He recommended finding an effective means of punishing the hostile bands of Shawnees and Mingoes for their “Insolence & Perfidy” without risking a wider and more destructive conflict for no gain. If a war erupted, he lamented that the backcountry inhabitants would find themselves “involved in misery and distress” in such an event.35

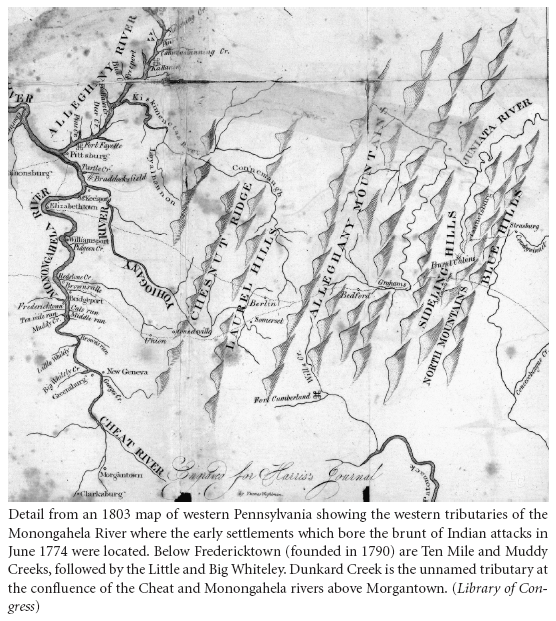

Indian fury fell hard on the Virginia side of the Ohio during the first week of June. The vengeance-driven Logan led a war party that hit settlements on Ten Mile, Muddy, Whiteley, and Dunkard creeks. All western tributaries of the Monongahela, their selection seemed to validate St. Clair’s belief that the Indians directed their hostility toward Virginia, not Pennsylvania. After arriving in the area, the war party divided into smaller groups to select their targets. Alerted to the raiders’ presence, the authorities warned local inhabitants to seek shelter at a nearby fort or a neighbor’s fortified home. Some, like William Spicer (sometime written “Spier” or “Spear”), who had intended to move his wife and seven children to the safety of the nearby Jenkins’s fort on Muddy Creek, had delayed doing so.36 The hesitation proved fatal.

According to their traditional way of war in such revenge raids, the braves struck the most vulnerable. Reflecting the attitude of many settlers, John Jacob described them as not an invading army “but a straggling banditti.” Isolated farms presented a favorite target, which they usually assaulted in the dark of night or at daybreak. They sometimes killed all of the family, at other times “only a part.” The attackers most often killed and scalped adult and adolescent males outright, as they considered them warriors, as well as small children. While other family members frequently suffered the same cruelty, Indians sometimes took women and older children, as well as some men, prisoner, after which they burned the houses and took all the horses. Captives not killed in the journey to Indian country still faced an uncertain reception there.37 After scouting the area between Dunkard and Big Whitely Creeks, Logan noticed that the Spicer family still occupied its farmstead.38

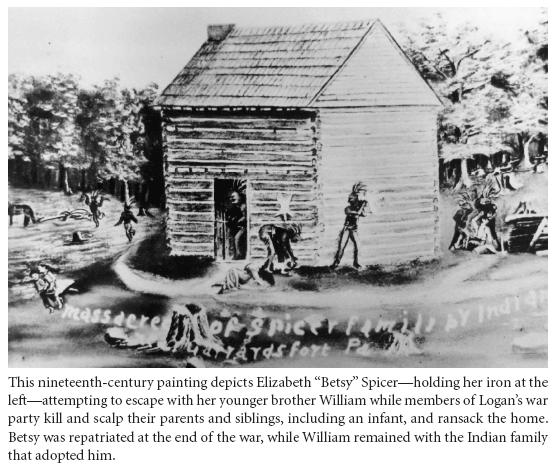

On the morning of Saturday, June 4, William Spicer was chopping wood in the yard near the family cabin. Inside, his wife, Lydia, tended to her two youngest children while twelve-year-old Elizabeth, or “Betsy,” ironed the family clothes. Outside, sixteen-year-old Job worked in the field while eleven-year-old William Jr. set traps for the squirrels attempting to feed on the young corn in the garden, and their two younger siblings mixed their daily chores with play in the meadow. When Indians emerged from the wood line and approached him, William stuck the axe into a log and headed for the cabin, possibly to retrieve refreshments to offer the visitors as a sign of friendship and peaceful intent. As the warriors followed, one of them—presumably Logan—grabbed the axe and drove it into the farmer’s skull from behind. He then burst into the house and treated Lydia and the two little children in the same manner. As the one intruder scalped her parents and siblings, Betsy, still clutching the iron, ran out the rear door.39

In her flight, Betsy grabbed little William and attempted to lead him by the hand to safety, but other warriors pursued and caught them, then forced them back to the house. As they drew close to the family cabin, a tall warrior named Snake came outside holding the wounded— but still living—youngest Spicer child upside down by the ankles. Betsy and William watched in horror as Snake bashed the infant’s skull against the wall. Out in the field, they saw another brave draw his knife while bending over Job’s lifeless body. After breaking its attachment at the hairline with the knife in one hand, he gathered a handful of the boy’s locks in the other. The Indian then tore the hair and skin from the crown of Job’s head to the nape of his neck, rose to his feet while holding the scalp high with an outstretched arm, and gave the horrific “scalp-yell” to announce his victory. The raiders plundered the Spicers’ food supply and possessions as they prepared to leave, while Logan warned the family’s two surviving children that he would kill them, too, if they attempted an escape or called out to alert would-be rescuers for help as the war party retreated to the concealment of the woods.40

Later in the day, passers-by reported finding Spicer “with a broad-axe sticking in his Breast, his wife lying on her back, entirely naked,” the lifeless and scalped corpses of the five children, and carcasses of all of the family’s cattle strewn about the property. The neighbors, not able to locate Betsy and little William, surmised the Indians had taken them captive. The same day, Dunkard Creek residents reported three other neighbors missing and presumed they had also been taken captive.41

Remaining in the area several more days, the warriors evaded militia patrols and emerged to attack vulnerable settlers when presented the opportunity. Logan and Snake led one group as they crept up on Jenkins’s fort and waited for any unsuspecting victims to come out and “fall into their hands.” They remained hidden behind a fence as they watched the detachment of militiamen who had buried the Spicer family return, and they waited for a more vulnerable and unsuspecting target. They waited tensely after hearing a female voice from inside the fort ask, “Who will turn out and guard the women as they milk the cows?” A squad of armed men emerged from the gate and scanned their surroundings, alert for any sign of hostile intruders, as the women went about their chores. More than once, Logan feared he and his companions had been discovered, and he contemplated making a run for it when a sentry pointed his weapon in their direction. But they waited until the guards turned their attention elsewhere. Finding no further opportunity to take another scalp or prisoner, the marauders rejoined their war party.42

The day after the Spicer massacre, and in the same neighborhood, a man imprudently took leave of his companions to go hunting. A short while later, they heard five shots off in the distance. When their friend’s horse returned with an empty saddle, the others went in search. They reported discovering the missing hunter’s coat riddled with a number of bullet holes and surrounded by footprints. On Tuesday, a party of Indians waiting outside the walls of Jenkins’s fort killed and scalped Henry Wall and a companion named Keener within sight of the people who had taken shelter inside. Connolly received news of these depredations, as well as reports from Wheeling that Indians had killed a man named Proctor at Grave Creek, and thus confirmed fears that at least one more war party, most likely Shawnees, remained at large south of the Ohio.43

To counter the raiders “about to annoy our Settlements,” Connolly detached one hundred militia soldiers in active service under the command of good officers to find and engage them, if possible. After warriors killed and scalped another settler just outside the fort at Redstone on the Monongahela, a thirty-man patrol met two individuals on the road who swore that they saw thirty Indians about five miles away. The militiamen immediately marched in the direction the informants had indicated but failed to find the enemy. Another thirty-man detachment went in pursuit of those who had murdered the Spicer family and others near Dunkard Creek. The lieutenant in command reported that his men managed to overtake the raiders, who chose to scatter and evade rather than risk an engagement. Although they killed none of the Indians, the militiamen rescued several captives and recovered some horses and other property plundered in the recent attacks. The raids had caused such panic that many people avoided travel on the main roads if they could. Like other well-to-do area families, brothers William and Augustine Crawford had convinced about a dozen families to join them in building forts adjacent to their houses, where neighbors could take shelter instead of abandoning their homes. The Crawford brothers also notified Washington that because of the emergency, William had enlisted the craftsmen and laborers employed at his western property into his company of militia.44

On Saturday, June 11, Captain Francis McClure and his second in command, Lieutenant Samuel Kinkade, led their forty-man company in pursuit of Logan’s warriors in the neighborhood of Ten Mile Creek above Redstone. Kinkade may have told the captain how his father, St. Clair, and other Pennsylvania officials reacted to the news that he had resigned his recent appointment as a Westmoreland County magistrate to accept a Virginia militia commission. Most of their conversation probably concerned the raids of the previous week in which Logan and his men killed and scalped an estimated sixteen settlers and took several others captive, like young Betsy and William Spicer. After receiving intelligence that someone had seen some Indians, they hastened toward the scene.

As the troops struggled up a steep ascent, the officers pushed ahead “rashly, with insufficient caution,” anxious to bring on an engagement and avenge the recent murders. A group of Indians waited in ambush, concealed in the thick foliage at the top of the hill.45 The warriors fired as the two officers came within range. One bullet struck the captain in the chest and killed him. Another tore into the lieutenant’s arm and caused a serious but not mortal wound. As the soldiers advanced to their fallen officers, they saw four warriors running from their concealed positions. Some of the men remained with the wounded Kinkade as the rest went in pursuit. The soldiers believed that they wounded one, but the Indians otherwise escaped without injury. After they buried McClure’s remains, the company marched home. Kinkade’s report confirmed that the war party remained at large in the Monongahela region.46

FEW EXPECTED an Indian war to remain confined to the Pittsburgh region. Colonel Abraham Hite, the county lieutenant, notified Governor Dunmore that hostile Indians had invaded Hampshire County. Warriors had attacked several farms on Cheat River in the first week of June. They killed inhabitants in their homes and cattle in the fields, which prompted the colonel to report “that a scarce day happens that but some cruelty is committed.” Opinions between Virginians and Pennsylvanians continued to differ. When he reported to Penn that Indians had caused “some Mischief” on the Cheat River and killed “eight or nine [Virginia] People,” St. Clair still questioned whether it signaled revenge for the massacre of the Yellow Creek Mingoes or the beginning of a war. In contrast, Hite wrote to Dunmore “that the many accounts of barbarity” made it “sufficiently obvious to anyone” that the Shawnees had resolved to declare war on Virginia. In consequence, he reported that people in the backcountry had either resorted to forting or moved away from the settlements.47

Farther south, warriors, suspected to be Shawnees, attacked a party of Floyd’s surveyors on one of the branches of the New River, a tributary of the Great Kanawha, in Fincastle County. The surveyors drove the Indians off, killing eight in a smart skirmish, but suffered the loss of eight men and a boy of their own party.48 Reverend John Brown wrote to his brother-in-law, Colonel William Preston, that war would probably come. Observing that “a great number under your Care whose dependence for protection (under God) is upon you,” the preacher urged Preston to be on his watch and to take every prudent method to prevent a surprise attack.49 As the county lieutenant, Preston needed no one to remind him where his duty lay. While he also held the posts of county surveyor and sheriff, and had represented his county in the House of Burgesses, he had a wealth of military experience. In addition to a life of service in the militia, he had commanded a ranger company defending the frontier during the French and Indian War.

Preston alerted and directed the captains commanding the Fincastle County militia companies to muster their troops and exert themselves “in keeping the people from abandoning their settlements” and “make them punctually obey orders.” Although the Militia Law had expired in July 1773, it remained in force, as everyone expected it would be renewed and continued in the current session of the General Assembly. Captain Daniel Smith agreed that the Invasions and Insurrections Act gave military officers sufficient authority over civilians and to employ the militia during dangerous times, and considered a recent amendment very helpful. The law gave the governor, county lieutenants, and other commanders of militia full power and authority to muster, recruit, levy (draft), and arm men to raise such forces of militia necessary to repel invasions, which included Indian attacks, suppress insurrections, or contend with other danger.50

To comply with the intent of the militia laws and the colonel’s orders, Smith scheduled a private muster of his company on June 12, or “as soon as the men could get notice as they live much dispers’d.” The captain expressed his concern over the scarcity of gunpowder and lead in his part of the county, a situation he described as “a Circumstance as alarming as any that occurs to me now.” Although the militia law required each man to keep one pound of powder and four pounds of lead at his home, Smith estimated that if called out to defend the community against an immediate invasion, his company had only an average of five charges of powder per man. Expecting a shipment from Colonel Andrew Lewis of Botetourt County, Smith learned that Major Arthur Campbell, the county battalion’s third-ranking field officer, had a large quantity reserved for such emergencies. In consequence, Smith sent Lieutenant James Watson to enquire of its suitability and availability and obtain a quantity for the company.51

AS CRUCIAL EVENTS transpired at Pittsburgh, Newcomer’s Town, and on the frontier, members of the Virginia General Assembly converged on the colonial capital at Williamsburg. Among the items on the agenda, the requirement to revise or continue the two defense-related laws arguably represented some of the most urgent business. Everyone knew that failure to act during the session could complicate matters with regard to the situation on the frontier. Despite their importance, other matters competed for the representatives’ attention in the coming legislative session.

In the fifth (1773) edition of his Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson defined “militia” as “that part of the community trained to martial exercise.”52 Earlier editions also included definitions such as “the standing force of a nation” and “The Trainbands,” with the latter further explained as “a name formerly given to the militia.”53 Johnson’s notes explained that he deduced the meanings from their usage in The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England, in which the author, Edward Hyde, first earl of Clarendon, explained “the militia . . . was so settled by law, that a sudden force, or army, could be drawn together, for the defense of the kingdom, if it should be invaded, to suppress any insurrections or rebellion, if it should be attempted.”54 When English settlers established the several colonies, they organized defense forces based on a common English militia tradition. Over time, each of the militias of the colonies adapted to local requirements and established new and unique traditions of their own.

According to his royal commission as governor, Lord Dunmore assumed responsibility for defending His Majesty’s colony and dominion of Virginia from invasions, suppressing rebellions, and pursuing enemies to the borders and out of the province. The legislation in effect when Dunmore arrived in 1771, as well as the pertinent clauses in his commission as governor and instructions from the Crown, reflected Johnson’s definition of militia and described the force at the governor’s command. Delegation of the king’s authority empowered the former British army captain “at all times to arm, to levy, muster and command” all persons living within the boundaries of Virginia. As royal governor he could call out, or issue the order to raise, as many regiments and march them anywhere within the province’s boundaries as he deemed necessary. In addition to enlisting volunteers, the governor could order the levy, or drafting, of men for active service as soldiers and artificers.55 The latter group included skilled mechanics and artisans, such as smiths, carpenters, and wheelwrights, along with wagon and packhorse drivers, woodsmen, and cattle drovers. These auxiliaries performed the necessary administrative and logistical functions that supported the line, or fighting forces, during periods of “actual service,” or active duty. They could do so either as members of the militia or as civilian employees. In addition, the governor could order the construction of fortifications, and impress, or commandeer, private property such as firearms, sloops, boats, draft animals, wagons, supplies, and provisions for military use. He also held the authority to proclaim martial law and issue letters of marque and reprisal to privateers in the king’s name during wartime.56

The governor’s commission did not grant him absolute military power. Virginia’s General Assembly, which mirrored the British Parliament in constitution and power, established the institutional structure of the colony’s forces in An Act for the Better Regulating and Disciplining of the Militia, more commonly called the Militia Law.57 In effect since 1757, the act defined the obligations of those who had to serve, specified their related responsibilities, and qualified the exemptions of those excused from performing service or attending training. It defined the colonial government’s role in supporting its military establishment, enforcing the act’s provisions, and maintaining order and discipline when its soldiers were not serving on active duty. An Act for Reducing the Several Acts for Making Provision Against Invasions and Insurrections into One Act, more commonly known as the Invasions and Insurrections Act, defined the colonial government’s responsibilities for defense and internal security, as well as the operational employment of the militia. The acts included provisions and procedures for raising and supporting militia forces when called into actual service, and enhanced military measures, such as organizing provincial standing forces, or regulars, “in times of danger.”58

Although based on a common tradition, the latter eighteenth century Virginia militia differed from its English counterpart in many respects. For example, the law that governed the militia in England required all able-bodied males eighteen to forty-five to enroll but required few to actually serve. The anonymous author of the preface to The Militia-Man, a handbook published in London circa 1740, wrote, “All men of property should serve in the militia” because they “each have something to lose” and “consequently . . . are fit persons to consider of the means of preserving it.”59 While individuals could volunteer, parishes selected men by ballot to fill their apportioned quotas to the county. After they completed a three-month period of training, militia members served the rest of their three-year terms in units that mustered to train periodically and responded to local alarms or augmented the regular army anywhere in England, but not overseas, during national emergencies. While the English militia recognized the king as its commander in chief, it also performed an important role in the constitutional monarchy as a safeguard against royal excesses. Reflecting the English fear of standing armies in peacetime, the militia existed to protect the rights and property of the citizenry from the army if the king chose to use the regulars as an instrument of domestic oppression. The Virginia militia, like its English counterpart, saw the king as its royal commander but stood ready to protect the rights and property of Virginians if he—or his colonial viceroy—violated the constitution and used the regular army to oppress them.

The Militia Law, like the Mutiny Act that governed the British army, remained in effect for a defined period. The terminating provisions of the Militia Law provided the General Assembly with the opportunity to evaluate laws and incorporate amendments, initiate changes, or repeal them. The process did not always prove easy. For example, when Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie addressed the General Assembly in November 1753, he reported that he found the militia “deficient in some Points.” He then urged the House of Burgesses to revise the Militia Law that had been in effect without substantive changes since 1738.60 It took the House another four years to pass an effective bill that addressed the problems, but not before the opening campaigns of the French and Indian War proved Dinwiddie’s observations correct.

Although the General Assembly had amended it twice and continued it four times to keep it current, the Militia Law enacted in 1757 remained in effect when Dunmore assumed office. Thomas Nelson, president of Virginia’s Colonial Council, signed the most recent continuance as acting governor in July 1771, only two months before the earl’s arrival.61 During the February 1772 session, the first over which Dunmore presided, the assembly voted to continue one, but not both, military-related laws. Although the Invasions and Insurrections Act was not due to expire until June the following year, the burgesses viewed it “expedient” to extend it early, for two years, or until 1774. The Militia Law therefore expired in July 1773.62

Expiration of the statute, however, did not abolish the colony’s militia. On February 6, 1773, Dunmore prorogued, or suspended, the General Assembly’s session until March of that year. That was followed by a series of prorogations that postponed resumption of the session until April of the following year, when the governor notified the General Assembly to reconvene in May 1774. When the legislative session was interrupted by this procedure, any law approaching expiration remained in effect until both houses had the opportunity to amend, continue, or repeal it in regular session.63

In contrast to the regular British army or other standing forces, an individual did not enlist in the Virginia colonial militia. The law required every free adult white male Virginia inhabitant eighteen to sixty to enroll, which gave the militia a nominal strength of nearly fifty thousand men in the early 1770s. It differed from the English militia of the period in that Virginia’s militia principally constituted a pool of manpower available for military service in an emergency rather than an organized reserve of the army. To fulfill his obligation, unless exempt from serving or otherwise excused from participating, each man was required to furnish himself with “a firelock well fixed, a bayonet fitted to the same, a double cartouche-box, and three charges of powder” and attend all musters and training exercises so equipped. Many of the eleven thousand men enrolled in the militia of the counties west of the Blue Ridge, particularly those in the frontier districts, armed themselves with rifles instead of muskets. Colonel Preston, the county lieutenant of Fincastle County in 1774, described the militia of his own and neighboring Botetourt and Augusta Counties as “being mostly armed with rifle guns” and therefore substituted a powder horn and shot pouch for the cartridge box, and a tomahawk in lieu of the bayonet to satisfy the requirements of the Militia Act. The law required every soldier to keep one pound of gunpowder and four pounds of lead, enough for about seventy rounds of ball ammunition for a musket, at his home, and to keep it well maintained and ready to bring whenever directed by his officers in the event of an actual alarm or when ordered into the field for active duty.64

The Militia Law did not exempt individuals if they could not afford to purchase the required items. Each county and the corporate boroughs of Williamsburg and Norfolk maintained public magazines with modest supplies of weapons and equipment marked as public property. If a court inquiry verified a member’s economic need, the county issued him the necessary arms, accoutrements, and ammunition from its magazine. Once able to do so, the man made payments until he covered the weapon’s cost. Otherwise, as soon as the poor soldier who required public assistance could afford to purchase his own arms and ammunition, or had been removed from the muster roles due to age, death, or other reasons, the captain in command of his company retrieved the county’s property and returned it to the magazine so it could be issued to another man of limited means.65

In 1712, during the War of the Spanish Succession, known in North America as Queen Anne’s War, the British government bestowed “a considerable quantity of arms and ammunition for the service of this colony” in order to better equip its militia. Two years later, in 1714, the General Assembly appropriated funds to erect a magazine at Williamsburg where “all arms, gunpowder, and ammunition now in the colony, belonging to the king . . . may be lodged and kept.” The weapons stored there, and in the entrance hall of the palace, were then available “to arm part of the militia, not otherwise sufficiently provided.” The General Assembly also voted to appropriate funds to employ a staff of two artificers, a “keeper of the magazine” to receive, issue, and account for the weapons and ammunition, and an armorer to maintain and repair them.66 The arsenal eventually housed other classes of munitions, such as pole and edged weapons, swivel and wall guns, cannon barrels, field carriages and artillery implements, as well as equipment ranging from tents, camp kettles, and entrenching tools to drums. The assembly made it clear that the arsenal did not replace the several local facilities. The munitions and supplies available at “his majesty’s magazine and other stores within the colony” improved the province’s ability to arm either standing forces or militia ordered on campaign by the government in Williamsburg.67

The Militia Act required all free men—white, black, and red—to enroll, but not everyone performed the duties of a soldier. The law traditionally exempted the clergy of the Church of England as well as the “president, masters or professors, and students” of the College of William and Mary, from their military obligations. While still required to enroll, the law also excused holders of public office, members of certain occupations or particular states of employment, and members of other specified classes from attending scheduled training assemblies, but not from owning and maintaining the necessary equipment, or from mustering with their companies in the event of an actual alarm. Quakers and members of other pacifist religious sects were excused from drill, performing military service, and having to possess weapons and accoutrement but had to contribute to the purchase of equipment for poor soldiers and furnish substitutes if they were selected in a draft for active duty. Because other laws prohibited them from owning firearms, the Militia Act required “all such free Mulattoes, Negroes, and Indians as are or shall be inlisted” to participate and assemble without weapons. Not permitted to train as soldiers of the line, these members served as drummers, trumpeters, artificers, pioneers, or “in such other servile labor as they shall be directed to perform.”68

The General Assembly delegated the means of enforcing order and discipline in its ranks to the militia itself. Officers and enlisted men received no pay for attending but faced fines of up to five pounds or confinement in the county jail and payment of prison fees to the sheriff for missing training assemblies without valid excuse, or failing to pass inspection by not having the required arms and equipment in their possession.69 Soldiers who committed acts of misconduct, refused to obey the commands of their officers, or behaved “prefactorily or mutinously” during assemblies became subject to stiffer disciplinary action. The Militia Act allowed “the chief commanding officer then present” to summarily impose punishment that included fines of as much as “forty shillings current money” and having an offender “tied neck and heels, for any time not exceeding five minutes,” but with no other corporal punishment, such as flogging on the bare back, permitted in peacetime.70 Courts-martial ordinarily convened the day immediately following a county’s general muster, provided the local inferior court had adjourned for the month, or as approved by the General Assembly. Before hearing cases, the empaneled officers swore to “do equal right and justice to all men according to the act of Assembly for the better governing and regulating of the militia.”71

The General Assembly established rates of pay for militia soldiers when they were called to perform active service or in response to alarms that lasted more than six days. The same per diem rates applied to provincial regulars when the assembly authorized the raising of standing forces. In 1774, soldiers received the following rates of compensation: “the county lieutenant or commander in chief ten shillings per day; a colonel or lieutenant colonel each ten shillings per day; major eight shillings per day; captain six shillings per day; lieutenant three shillings per day; ensign two shillings per day; serjeant and corporal each one shilling and four-pence per day; drummer one shilling and two pence per day; [private] soldier one shilling per day.”72

In addition, except for criminal charges, the law “privileged and exempted” militia members from arrest while going to, attending, or returning from musters and protected them “from being served with any other process in any civil action or suit” while on duty. At no time could the military items that the law required them to possess be “distressed,” or seized, to satisfy creditors in any judgments. When men were ordered to active service in the colony’s pay, the law exempted them from having to pay province, county, and parish levies, including any new taxes enacted by the General Assembly during their absence on military duty, as well as “privileged” soldiers’ private estates from civil court action for indebtedness.73

Although the law mandated compulsory service for all, the militia from time to time suffered a lack of citizen interest or governmental neglect, especially when no apparent or perceived threats to peace and colonial security existed. Understandably, inhabitants on the frontier took more interest in their militia participation than those in more-secure regions, such as the Tidewater, “on account of the frequency of Indian atrocities.” Drummer Joseph Tennant, of Captain James Parsons’s company of Hampshire County militia in 1774, explained that in the backcountry communities, “Every man learned the use of fire arms from necessity . . . and were taught a certain amount of military discipline.”74

For whatever reasons, some men preferred paying the fine, or hoped that indifferent county courts would neglect to enforce the law, rather than attend training assemblies. Others refused to turn out when summoned for active service. In contrast, still other Virginians viewed participation in the militia as an avocation. Such officers and members of the rank and file took training and service seriously and developed military skills and prowess that exceeded those of most of their peers. More importantly, their county and colony counted on such men, who usually volunteered at the first alarm and often served repeated tours of duty. In a land devoid of native hereditary aristocracy, most militia officers valued their commissions. Many preferred to be identified and addressed by their titles of rank in public discourse as well as correspondence for the rest of their lives and took them to the grave by having them carved on their headstones.

While many of the colonies were similar in their militia establishments, differences could be found. Where some other colonies elected their leaders, members of Virginia’s forces did not. Commanders at various levels appointed subordinate officers and noncommissioned officers. Justices of the inferior courts could suggest candidates for consideration, and members of the council offered their advice and consent on the appointment of field officers, but only the royal governor had the authority to sign and issue commissions.75 By “reposing special Trust and Confidence . . . in the Loyalty, Courage, and Conduct” of a deserving gentleman, the governor extended the status as an officer, with all the inherent responsibilities as well as privileges involved, in the name of His Majesty.76

Each major political subdivision had its “Chief Commander of all his Majesty’s Militia, Horse and Foot” who answered to the governor. Given the title of county lieutenant in each of the sixty-one counties, or chief commanding officer in the boroughs of Williamsburg and Norfolk, this officer held “Full power and Authority to command, levy, arm, and muster” all those available for military service residing within the limits of his jurisdiction. In case of a “sudden Disturbance or Invasion” or other emergency, the county lieutenant could “raise, order, and march all or such part of the said Militia” as he deemed necessary to resist and subdue the enemy.77

Each chief commanding officer held the rank of colonel, and his commission took precedence before that of any other officer holding equal rank. Otherwise, he observed and followed the orders and directions of the royal governor and “any other . . . superior officer” appointed over him in accordance with the “Rules and Discipline of War.” Otherwise, a second colonel often functioned as the deputy county lieutenant and field commander. Some county lieutenants treated their positions more like a civil office and attended only to its administrative requirements while leaving purely military matters to a subordinate field officer.

To organize Virginia forces, the Militia Act required the county lieutenants and chief commanding officers to “list all male persons within this colony (imported servants excepted)” from eighteen to sixty. The county lieutenant then divided the county into nine geographical catchments based on the distribution of the military-age free white male population. Each catchment constituted one company of foot, with possibly one troop of horse organized from the county at large. The county lieutenant placed the soldiers thus organized “under the command of such captains as he shall think fit” to appoint and receive a commission from the governor.78 After he consulted the subordinate field officers and captains commanding the companies, the county lieutenant appointed the necessary subaltern officers, or the lieutenants and ensigns in companies of infantry, or lieutenants and coronets in troops of cavalry.79 After an officer received his commission bearing the royal governor’s signature, he swore the necessary oaths required to affirm his loyalty and pledged his service “for the security of his majesty’s person and government.”80 Each captain appointed the noncommissioned officers and musicians in his company as well as a clerk who kept the muster rolls and maintained the records. Soldiers could not decline appointments to positions of increased authority or responsibility without consequences. One who refused to serve as a sergeant, corporal, drummer, or trumpeter “as required by his captain” became subject to a monetary fine imposed by the county court for every muster that he continued to refuse the appointment.81

Although designated a company and commanded by a captain, the local unit primarily functioned for administrative and training purposes only. These administrative companies were often larger than the tactical organization of fifty rank and file established for a company of the line when organized for active service, and they rarely took the field as units except when called out for an alarm. For example, on being notified of an invasion or insurrection, the law required every officer to “raise the militia under his command,” dispatch express messengers to inform his immediate superior commanding officer of his actions, and “immediately proceed to oppose the enemy” with the number of troops available until he received orders directing him to do otherwise. Similarly, on receiving word of an alarm in an adjacent county, the law obliged the chief commander of militia to “immediately raise the militia of his county” and detach as many as two-thirds of his men to engage the invaders or insurgents. The county lieutenant then organized the remaining third to remain in arms for the “defense and protection of the county,” and waited on orders from the governor.82

The companies primarily served as sources of trained manpower from which the colony could organize tactical units for “actual service,” or active duty, in periods of emergency. To make the force “more serviceable,” the Militia Act held officers responsible for their men’s readiness and compliance with the law. A captain, for example, ensured that all the soldiers in his company were properly armed, equipped, and trained. In peacetime, the statute required him to conduct a “private muster” in the local neighborhood at least once every three months and more often if he or the county lieutenant deemed it necessary. After the captain inspected his men and took “particular Care” to see that they all possessed the necessary arms and ammunition, he trained his company according to the Manual Exercise as Ordered by His Majesty in 1764.83 The manual reflected the British army’s experience on European battlefields during the Seven Years’ War and concentrated on the essential elements of individual and platoon drill, evolutions and maneuvers, and firings.

In addition to observing the several private musters throughout the year, the militia law required the county lieutenant to train all the companies under his command once a year at an annual “general muster and exercise,” usually in March or April. When wartime necessitated enhanced readiness, the General Assembly often increased the frequency of company musters to once every month, or every other month, and added a second general muster for all counties in September or October as well.84 It is arguable that British regulars posted in widely dispersed garrisons in peacetime received as much training in regimental-sized formations as Virginia militiamen did by attending their general musters.85

Like the company musters, the general musters also began with the ubiquitous inspections to ensure all officers and men had the arms and ammunition the law required. The companies then trained collectively and practiced the elements of the manual that applied to battalion formations. Ideally, two platoons operated in a tactical company-sized unit called a subdivision. Two subdivisions combined to form one grand division. An entire tactical battalion organized on the regular British model consisted of four grand divisions of four platoons each, arrayed in three ranks, and trained to execute the appropriate evolutions and maneuvers with some degree of proficiency. Finally, given the limited time available, a battalion strove to master the most critical elements of all, “firings,” either by “ranks entire” or by platoons, subdivisions, and grand divisions in the elaborate sequence and precise order of rolling volleys that enabled it to deliver a near continuous volume of musketry. Victory on the eighteenth-century battlefield often went to the side that could throw the most lead at its opponent in the quickest time.86 Such exercises would have been the norm in the more settled regions, as reflected in the militia law enacted in 1740, to “establish our Militia on such a Footing, that in case of Invasion or Attack, they may be enabled to contend with regular Troops.”87 Given the threat they would more likely face, the militia of the frontier counties spent more time practicing light infantry-style tactics adapted to the probability of fighting Indians in the woods.

As part of the plan to further enhance readiness and ensure compliance with the Militia Act, Governor Dinwiddie eliminated the office of the single colonial adjutant general on the eve of the French and Indian War. He divided the colony into the Northern, Southern, Middle, and Frontier Military Districts, and assigned an adjutant general to each. Receiving an annual stipend of £100, and usually holding the rank of major, each adjutant general reported to the governor on compliance with the Militia Law in the counties that comprised his district.88

In performing their duties, these officers attended all the battalion general musters in their districts. To perform their duties, they were instructed to “exercise the Officers first” in order “to qualify them to exercise each separate Company” and prepare them for their respective general musters.89 During an inspection, they ensured that all company officers had their men “properly trained up in the use of Arms,” and “more perfect and regular in the Exercise thereof.”90 Finally, performing a role similar to a brigade major or adjutant in the British army on regimental field days, they inspected “all detachments before they be sent to parade” and saw that all “their arms be clean, their ammunition, accouterments, &c. in good order.”91

With all sixty-one counties and two independent boroughs in the colony required to conduct their general musters in March and April, the adjutants general faced challenging spring schedules. The county lieutenants therefore had to plan their annual training assemblies based on the date they expected the district officer’s presence. The counties involved in Dunmore’s War were among the fourteen that comprised the Frontier Military District, where Captain Thomas Bullitt served as adjutant general. The veteran officer had served in the 1st Virginia Regiment throughout the French and Indian War, remained active in the militia, and had actively sought the assignment before Governor Botetourt appointed him on May 10, 1769.92

Due to the remoteness and difficulty reaching some of the locations in his district, the newly appointed adjutant general used public notices, called advertisements, in the March 22, 1770, edition of Rind’s Virginia Gazette to notify the thirteen county lieutenants of his schedule. (The law that erected Fincastle County was enacted in 1772.) In 1771, because the General Assembly had not yet voted to continue the Militia Act due to expire, Bullitt acted on his “former appointment” to announce his itinerary in the February 5 edition of Purdie and Dixon’s Virginia Gazette. Unless prevented by “high water” or other unforeseen circumstances, Bullitt expected to be present at their county courthouses on the dates indicated. Since they all outranked him, and considering the schedule he had to maintain, he requested that the county lieutenants “oblige him” by assembling their militia “in good Order, and accoutered as the Law directs” at that time.93

Bullitt’s responsibilities as a surveyor, which took him on an expedition to the Falls of the Ohio and the site of present-day Louisville, Kentucky, prevented him from inspecting the district’s general musters in 1773. Fortunately, the counties of the Frontier District benefited from having a number of field officers, senior captains, and noncommissioned officers who had combat experience in the French and Indian War while serving with the provincial standing forces. Colonels Adam Stephen and Andrew Lewis, the county lieutenants of Frederick and Botetourt Counties, respectively, had served as officers under Colonel Washington’s command in the Virginia Regiment and commanded volunteer battalions in Pontiac’s War. Colonels Charles Lewis (Andrew’s brother) and William Preston, the respective county lieutenants of Augusta and Fincastle Counties, had served as officers in provincial ranging companies.

With renewal of the Militia Act and the possibility of an Indian war weighing heavily on their minds, the Lewis brothers and William Christian of Fincastle County took their seats in the capitol on Thursday, May 5. In addition to holding elective office as representatives in the lower legislative house, they also held commissions as field officers—colonels—in the militia of the westernmost counties. The men most knowledgeable as well as responsible for the defense of the colony’s frontier sat with their fellow members of the House of Burgesses as Governor Dunmore welcomed them for the “necessary business of this Colony” and charged them to “proceed with dispatch which the Publick convenience requires.” After making and passing the necessary pro forma resolutions of thanks to the governor for his opening address and congratulating him on the safe arrival of his wife, Charlotte, the Countess Dunmore, and their children, in February, the assembly turned its attention to matters of government.94