CHAPTER 5

The Present Exigence

Military Mobilization

May–July 1774

AFTER THE Governor’s opening address on May 5, Speaker Peyton Randolph brought the House of Burgesses to order to discuss the matters before the lower house for that session. The dispute with Pennsylvania, Indian hostility, and the expiring Militia Act took their places on the calendar. To further complicate their legislative tasks, the burgesses also had to find a way to express Virginia’s solidarity with the other colonies in their disapproval of the Boston Port Act before it went into effect on June 1. Before the various bills, resolutions, and even routine matters came to the floor, they made their way through committees.

On Wednesday, May 11, John Blair Jr., the secretary of the council, delivered the governor’s address concerning the boundary dispute and military situation on the frontier, which Randolph read to the members of the House. Lord Dunmore explained that he extended Virginia’s jurisdiction to the Forks of the Ohio region in order to counter Pennsylvania’s “pretended claim to this Country,” which, he said, was “founded on a partial survey.” He justified his order for officers to assemble a militia in accordance with Virginia’s laws after he observed the “defenseless state of a considerable Body of his Majesty’s Subjects settled in that part of the Country” and believed it was his duty to defend them. The next day, the governor requested that the speaker read to the burgesses Connolly’s recent report about “some Hostility commenced by the Indians.”1 The burgesses agreed with the governor’s actions and concurred with his recommendation to establish a temporary boundary until the king approved a “true and proper” permanent border. A committee drafted a formal response in which the members of the House expressed the desire for continued friendship “with our Sister Colony Pennsylvania” and an equitable resolution of the boundary dispute.2 Governor Penn had previously dispatched three commissioners to Williamsburg to meet with his Virginia counterpart in person, looking to accomplish the same goal.3

The General Assembly turned its attention to military matters at the capitol. The king may have delegated the power of the colonial sword to Lord Dunmore by his royal commission as governor and commander in chief of Virginia, but the House of Burgesses held the power of the provincial purse. He had the authority to organize and command provincial standing forces, call the militia into actual service, and order troops to conduct operations, but unless the House of Burgesses consented on behalf of those they represented, and voted to levy the taxes to raise the necessary revenue to pay for military expenses, the governor’s war powers had no effect.

Dunmore had informed the burgesses that he did not consider the militia equal to meet the Indian threat on the frontier and urged them to pass legislation to raise and organize a corps of regulars in the colony’s pay. He argued that regular soldiers would be subject to military discipline and training as soon as they enlisted, and held the opinion that standing forces, by their very nature, were more effective, economical, and reliable than militia. The governor maintained that simply by having them, the colony would demonstrate its determination to vigorously defend the frontier and have the capacity to conduct timely expeditions of reprisal against the Shawnees, as well as deter other potential enemies in the future.4

If the lower house was going to approve Dunmore’s request for regulars during this session, its members had to quickly pass the legislation. The lower house members had more confidence in the militia than their governor, and calling militiamen into actual service offered the parsimonious burgesses an attractive alternative to regulars. The county lieutenants could form units, by recruiting volunteers and by draft, to meet the emergency in a relatively short time, and disband them, discharging the men quickly, as soon as hostilities ended. In addition, unlike standing forces, they could appropriate the expenses incurred in arrears by employing the militia. The Militia Act provided a process in which members of the House appointed commissioners who reviewed all the accounts for military expenses, including soldier pay as well as for material and services given voluntarily or impressed, and reported their findings to the committee of the whole. If the House approved payment by majority vote, the speaker instructed the colonial treasurer to disburse the money.5

The burgesses determined that using the militia was more appropriate and less expensive than regulars. On Friday, May 13, Speaker Randolph advised Dunmore that the war powers, which were “fully invested” in the governor’s office under the existing Invasions and Insurrections Act, sufficiently empowered him to deal with the “hostile and perfidious Attempts of the savage and barbarous Enemies” who had commenced hostilities against his Majesty’s subjects.6 Dunmore replied the next day that while he was aware of the frugal burgesses’ desire to “advance the Prosperity” of the colony, he believed the act they had cited did not enable him to “raise a sufficient force for repelling the Attempts of the Indians” in the most economical way. He appreciated their desire for economy but disagreed with their reasoning and maintained their resolution would produce the exact opposite result of what they intended. Although he stated that in the end, a force of regulars would cost the colony— that is, the burgesses’ constituents—less money while affording their “dearest interests” more effective protection, he accepted the decision.7

As the House turned its attention to other issues, the laws pertaining to colonial defense made their way through the legislative process. On May 19, the representatives voted to continue the Invasions and Insurrections Act, with an amendment, and passed it on to the council for its consent. The bill to renew the Militia Act remained in the House’s Committee of Propositions and Grievances. The lower house’s Select Committee of Correspondence then informed the committee of the whole that it had read and replied to the legislatures of the other colonies on the status of their collective grievances with the government of Great Britain. Virginians, like most other American colonists, saw the Tea Tax as an unconstitutional attempt to raise revenue without their consent. While they disapproved of the destruction of private property—the East India Company’s tea—by Boston’s Sons of Liberty the previous December, they deplored the heavy-handed British government’s reaction even more.8

On Wednesday, May 24, the House met to discuss the Boston Port Act, the first of the Coercive—or “Intolerable”—Acts passed by Parliament, scheduled to go into effect in one week. The burgesses regarded it as the “hostile Invasion of the City of Boston, in our Sister Colony of Massachusetts Bay,” and a threat to the liberty of all American colonists. “Being deeply impressed with apprehension” of the act’s provisions to close Boston harbor and halt the city’s commerce, the lower house resolved to take action in protest. The House ordered that Wednesday, June 1, would be observed as a day of “Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer.” Starting at ten o’clock in the morning, the speaker and mace would lead the assembled representatives in a solemn procession from the House chamber of the capitol down Duke of Gloucester Street to the Bruton Parish Church. Inside, they would devoutly implore God’s “divine interposition for averting the heavy Calamity that threatens destruction to our Civil Rights and the evils of civil War.” The burgesses intended the action to show their solidarity with the people of Boston and join fellow colonists as loyal subjects of the king to speak with “one heart and one Mind” to firmly oppose “by all just and proper means, every injury to our American Rights.” They would offer prayers asking God to inspire the king and “his Parliament” with the “Wisdom, Moderation, and Justice” to remove any threats to the rights of loyal British Americans. After the House of Burgesses directed the order published in the House Journal and newspapers, and on broadsides announcements posted around Williamsburg, the members resumed business to address routine matters for the next two days.9

While the representatives worked at the capitol, Pennsylvania’s royal attorney general, James Tilghman, secretary of the colony’s land office, Andrew Allen, and barrister Richard Tilghman arrived from Philadelphia to address the boundary dispute with Lord Dunmore.10 He received them at the palace on May 21, and Governor Penn’s commissioners began the discussion. They articulated the Pennsylvania position on the proposed location for an interim boundary that could resolve the issue of “clashing jurisdictions” until the king settled the matter permanently. When they submitted their written justification for the proposed line, which put Pittsburgh within Pennsylvania’s boundary by five miles, Dunmore rejected it on the grounds that their calculations were in error.11

The Virginia governor countered with a “true construction” based on his understanding of the royal grant to William Penn. Using the description of its width to determine the western boundary and “running eastwardly,” Dunmore determined that Pittsburgh was located fifty miles outside of the grant’s area. The Virginia governor stated, “Your proposals amount in reality to nothing and could not possibly be complied with.” When their negotiations ended on May 27, Dunmore told Tilghman, Allen, and Tilghman to inform Penn that his government would not relinquish its jurisdiction of the area without orders from the king. The Pennsylvania commissioners thanked the governor for his polite attention and the “dispatch” he gave their business. They departed Williamsburg the next day.12 The council “highly approved” of Dunmore’s conduct as the “Negotiations came to Nothing.”13

On May 26, John Blair entered the House chamber during a discussion about the salary of the minister of Shelburne Parish in Loudon County. Addressing Speaker Randolph, Blair announced that the governor commanded the House to attend his excellency immediately in the council chamber. They went upstairs and across to the wing of the capitol where the upper house convened. When Randolph assured the governor that all had arrived, Dunmore addressed the speaker and the gentlemen of the House of Burgesses. He explained, “I have in my hand a Paper published by Order of your House, conceived in such Terms as reflect highly upon his Majesty and the Parliament of Great Britain; which makes it necessary for me to dissolve you.” He then announced, “You are dissolved accordingly.”14 Despite dissolution by Dunmore and their collective grievances with recent acts of Parliament, the burgesses remained loyal subjects of the king and still hosted “A grand ball and entertainment” at the capitol that evening to celebrate the arrival of the Countess Dunmore.15

Dunmore later explained that his “good friends the Virginians” showed themselves a “little too High spirited” but claimed that he took them by surprise. Satisfied with his action, he told General Gage that he believed his actions had caused most of the burgesses to “repent sincerely for what they did.”16 Instead of repenting, eighty-nine burgesses reconvened at the Raleigh Tavern the next day and agreed to form a nonimportation and nonexportation association, and they called for a Virginia convention and a general congress of all the colonies.

The dissolution did not abolish the House of Burgesses and representative government in the colony but called on the voting freeholders to reconstitute it. Dunmore’s action was an exercise of the executive prerogative vested in his office that previous governors had used on occasion. Many burgesses knew they would return to their seats in the capitol before long. In the meantime, the governor had to issue writs for new elections, at which time constituents would vote to reinstate or replace their representatives. Once accomplished, the governor would call the General Assembly into session and resume the process of enacting laws.

Unfortunately, the dissolution halted progress on some important legislation. The bill for an amended Invasion Act had only made it to the council for consideration. The overdue continuation of the expired Militia Act had yet to clear the Committee for Propositions and Grievances for its third and final reading, and a vote by the House. As when the governor had prorogued the General Assembly, all expired laws remained in effect until the governor called the General Assembly into a new session. Where a prorogued session could continue the legislative process when the session resumed, the new House of Burgesses had to start it anew. The expiration of the Militia Law did not disband the militia. Until both houses had the opportunity to vote whether to continue, amend, or repeal the invasion and militia laws, they remained in effect. Those who might use the expiration of the Militia Act to shirk their military obligations stood vulnerable to prosecution.

Amid the controversy about the closing of Boston harbor; the day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer; and the continuing constitutional crisis between the colonies and mother country, both editions of the Virginia Gazette for the week carried news of the simmering hostilities on the Ohio. One article warned readers, “We believe with much certainty that an INDIAN WAR is inevitable, as many outrages have lately happened on the frontier.” The causes still seemed unclear to many who did not live in the backcountry. The article accurately concluded that “whether the Indians or whites are most to blame, we cannot determine, the accounts being so extremely complicated.”17

THE EFFORT to repair Fort Pitt neared completion. Connolly ordered four hundredweight—or 448 pounds—of gunpowder for the militia from the B. and M. Gratz merchant house of Philadelphia to ease the shortage of ammunition. In addition, he ordered a British “union flag of five yards to hoist at the Fort—also to be made of the woolen stuff called bunting.” In a letter to Michael Gratz, John Campbell, the company’s agent in Pittsburgh, wrote that Connolly’s efforts had put Fort Pitt “more in a better posture of defense than I ever saw before.”18

As leader of the Pennsylvania faction in the border dispute, St. Clair had become an outspoken critic of Governor Dunmore and Captain Connolly. Even Croghan had apparently begun to hint at a renewed allegiance to Pennsylvania. St. Clair and his fellow Westmoreland County magistrates charged that Connolly’s Virginia militia had run roughshod over the inhabitants who remained loyal to Pennsylvania. He complained they had “harassed and oppressed the people” and “lay their hands on every thing” they wanted without asking, and “killed people’s cattle at their pleasure.” Connolly replied that as the Invasions and Insurrections Act required, his officers appraised all the property they impressed for military purposes and presented the citizens thus deprived with “a bill on Lord Dunmore” for payment. St. Clair described the practice as a “downright mockery.”19 It may have surprised the captain commandant, but many Virginians did not hold a high opinion of him either. Although never insubordinate, even William Crawford confided to George Washington that Connolly had “incurred the displeasure of the people.”20

In a report to Governor Penn, St. Clair expressed his hope that the crisis would reveal “some of the devilish schemes” carried out by Connolly and other Virginia partisans, or possibly Dunmore himself. He even maintained a belief that an Indian War, provoked either on Dunmore’s orders or Connolly’s own volition, was part of the Virginia plan, which morally strengthened Pennsylvania’s position in the boundary dispute. The substantial expenses incurred by repairing Fort Pitt and calling out the militia required an appropriation from the colonial treasury to satisfy, or it would fall to Connolly’s personal responsibility. St. Clair knew that the Virginia General Assembly would only levy taxes to cover the expenditure if they appeared sufficiently necessary to justify the debt. St. Clair therefore believed the governor had planned, while Connolly executed, the incidents that had provoked the Shawnees and Mingoes to hostility—if he could only prove it.21

It seemed St. Clair and the rest of the Pennsylvania faction did not have to prove anything. At the beginning of June, Major General Frederick Haldimand reported to the secretary of state for the colonies, Lord Dartmouth, that he had received information about the Yellow Creek massacre, “though not from any of the governors or any persons in the Indian department, that one Colonel Cressop from Virginia . . . has of late been on a scout against Indians inhabiting about the Ohio and killed several of them.”22 Later in the month, Sir William Johnson similarly notified Dartmouth that he “received the very disagreeable and unexpected intelligence that a certain Mr. Cressop, an inhabitant of Virginia, had trepanned and murdered forty Indians on Ohio.”23 Johnson further explained to Haldimand that the Indians had considered the attack on their people and scalping of their dead, attributed to Cresap, as a declaration of war.24

The roving war parties spread such chaos that it presented the Pennsylvania government an opportunity for recovering the part of Westmoreland County lost to Virginia. Under the threat of attack, but holding to his belief the Shawnees and Mingoes bore no hostility toward Pennsylvania, St. Clair made two recommendations. With no colonial militia to call on, St. Clair, Croghan, McKee, Butler, Mackay, and Smith, along with other pro-Pennsylvania residents of Pittsburgh, entered into a private “Association” to raise, provision, and pay for a ranging company of one hundred men for one month. Optimistic that the company would recruit its volunteers in a short period of time, he asked the governor to request that the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly assume the expense of keeping the men in service for a longer duration. St. Clair justified the cost by adding that under such protection, Pennsylvania colonists were less likely to desert their homes and farms in panic. Furthermore, he informed the governor that some Pittsburgh inhabitants had proposed to erect a stockade to fortify the town. Should negotiations with Dunmore’s government not satisfactorily resolve the boundary dispute, St. Clair suggested that having rangers under arms afforded Pennsylvania the ability of “throwing a few men into that place” to lead the effort, which “would recover the Country the Virginians had usurped.”25

Carlisle merchant John Montgomery noticed the people of Westmoreland County in “great Confusion and Distress,” with many fleeing east and some building forts. He appealed to the governor and assembly to provide enough arms and ammunition to defend the frontier settlements. Montgomery believed that an Indian war that involved Virginia would eventually also include Pennsylvania. Despite the assembly’s aversion to military spending, Penn had to convince the house of its obligation and the necessity of raising and paying soldiers. He argued that at the very least, Westmoreland County needed a militia organization. Montgomery further recommended that a unit of full-time soldiers—like St. Clair’s rangers—should be enlisted to patrol the settlements, intercept Indian war parties, and build or improve forts at Pittsburgh, Hanna’s Town, and Ligonier for the duration of the emergency to encourage Pennsylvanians to make a stand.26

If St. Clair and his associates hoped the news of a ranging company forming at Hanna’s Town would alarm Connolly and the Virginians, their hopes were realized. Croghan told the Virginians not to worry, because they would only operate between the Kiskiminetas River and Ligonier to help stem the flight of panic-stricken Pennsylvania inhabitants. He envisioned that if circumstances necessitated, the rangers would act in concert with Virginia forces for the general defense of the country against a common foe and not at cross-purposes. Croghan therefore urged St. Clair to exercise prudence and caution and not employ his rangers to “Invade ye Rights of Virginia” and thereby rekindle the war of words between the two governors, which would do nothing to resolve the boundary dispute.27 St. Clair assured Penn, “In a very particular manner, our Soldiers are directed to avoid every occasion of dispute with the People in the Service of Virginia.”28

CONCERN FOR the fate of the traders still in Indian country continued to increase despite Cornstalk’s pledge to provide escorts and safe passage. The day after the eleven traders from Newcomer’s Town arrived in Pittsburgh, Connolly learned that a number of warriors went to the Canoe Place on the Hockhocking River bent on killing some of the whites who frequently gathered there.29 Word reached Pittsburgh on June 12 that hostile Mingoes had killed and scalped a trader named Campbell at Newcomer’s Town, where Duncan and Anderson had found sanctuary the previous month.30 According to Reverend Heckewelder, other traders found “true friends” among the Delawares, who put themselves in danger for their kindness. The Delawares who escorted many fleeing traders to safety in Pittsburgh not only had to avoid hostile Shawnees and Mingoes but risked the likelihood that jittery militiamen might mistake them for an invading war party and open fire.31

A number of friendly Indians guided groups of traders to places of refuge on their side of the Ohio. One Delaware woman, for example, “espied” the Baptist clergyman David Jones and two traders as they traveled together on the Muskingum. After warning of the danger awaiting them if they continued in the direction they were heading, she led them along a route that allowed the men to “escape the vengeance of the strolling parties.” Although safer, the terrain proved extremely difficult, and it so fatigued one of the traders that he admitted he preferred death to exhaustion. When the group finally struck a path, he decided to follow wherever it led and bade the others farewell. After he had gone only a few hundred yards, fifteen Mingoes took him captive within sight of White Eyes’ Town, about ten miles upstream from Newcomer’s Town. He would have reached safety if he had remained with the woman, but as Jones later told Heckewelder, the Mingoes ritually tortured, scalped, and executed him. The warriors dismembered the man’s corpse, hung his limbs and flesh on bushes, and celebrated their triumph by yelling the scalp halloo. When White Eyes heard the noise, he led some Delaware warriors to investigate, but they were too late. When they arrived, they could only collect and bury the remains. The next day, angry Mingoes exhumed and rescattered the victim’s body parts. Once again, the Delawares recovered and reburied them. The infuriated Mingoes entered the town, condemned the Delawares’ conduct, and pledged to “serve every white man they should meet in the same manner.”32 Undeterred by their threats, White Eyes kept most of the Delaware neutral.

A trader’s store was located in the Delaware town of the Standing Stone on the Hockhocking River. The men who operated such franchises acquired pelts from Indian hunters in exchange for manufactured wares such as cloth, ammunition, firearms, ornaments, and other goods. During the period the trouble began, the principal trader left on the two-week journey to the company factory at Pittsburgh, where he would exchange pelts for merchandise to bring back to the Indian town. He left John Leith, his seventeen-year-old employee, to mind the store in his absence. John was resting on some skins one morning when an Indian boy entered the store. The boy told John that his father, a local chief, wanted to see him immediately.33

On entering the dwelling, the chief motioned for John to sit while a white woman, who Leith assumed to be his wife, translated the Indian’s words into English. After they exchanged greetings, the older man asked if John had heard that war had broken out between the whites and Indians. The boy listened with wonder and surprise as the chief told him that Shawnee warriors had recently killed seven white men and captured four others in the area. Recounting the causes of the current hostilities, the elder told the youth that “the Virginians had taken Mingo Town” and massacred Logan’s relatives. John answered honestly that he had “heard nothing about it.” Believing that he stood accused, John stated, “I had never done any of them harm,” and swore he had “no hand in the matter.”

The chief then gestured for John to rise to his feet, and with a “fearful expectation” that the chief intended to kill him, he tried to steel himself for the blow of a war club that would surely follow. Instead, the chief put him at ease, pointed to his wife’s breasts, and said, “Your mother has risen from the dead to give you suck.” He then continued, “Your father has also risen to take care of you, and you need not be afraid, for I will be a father to you.” With those words the older man embraced John about the neck to signify that he had formally adopted him. The chief then called on all the town’s headmen to meet at the store. After making a brief announcement in their language, “they proceeded to divide the store-goods, spirits, and all that I had care of among themselves.”34

WITH HOSTILE Indians attacking “the back parts of this Country” to commit “outrages and devastations,” Dunmore issued a circular letter to the county lieutenants listing their responsibilities for meeting the crisis. As they could no longer entertain any “hopes of pacification” with the hostile bands of Indians, he took the opportunity to criticize the General Assembly for not having thought it proper to pay more attention to the situation on the frontier, “though they were Sufficiently appraised of it.” He alluded to the burgesses’ passing the irresponsible resolution to hold the day of fasting and prayer to protest the Boston Port Act before voting on the more pressing necessity of renewing the colony’s expired Militia Law. He then outlined the only means left to “extricate ourselves out of so Calamitous a Situation” and explained how the militia would continue to function while faced with an Indian invasion.35

The governor informed General Gage that the Indians had “most certainly broke out and murdered a good number of our people,” consequently, “all our thoughts must now be turned that way.”36 Under the authority of his royal commission, and responsible for Virginia’s defense, Dunmore ordered the county lieutenants to embody—or activate—their militia to stand in readiness to respond to alarms, although he had not yet called them to the colony’s service. In the absence of a current militia law, he expected them to exert the powers vested in their offices “that may answer the present exigence.”37

Dunmore directed the county lieutenants to take the routine precautions found in the Militia Law and every officer’s commission. He emphasized the importance of captains holding private musters to ensure the men had the required arms and ammunition and practiced the prescribed drill. Of equal importance, he urged the county lieutenants to “keep up a constant Correspondence” with their counterparts in adjoining counties and assist one another, and if necessary, combine their “respective Corps of Militia into one body.” Aware of the shortage of ammunition, Dunmore promised to provide them with powder and ball on his own credit should the General Assembly not appropriate the necessary funds in the next session after reinstating and continuing the Militia Act. He recommended that the county lieutenants have their men erect small forts where the inhabitants could find protection and the county could secure its important documents, and from which, if the militia was compelled to give ground to a large invasion, its retreat could be covered. He left it to their judgment as to where to build the forts and how many to build. The governor believed that the construction of a substantial fort at the confluence of the Great Kanawha and Ohio Rivers would answer several good purposes. While he encouraged them to build such a fort, he left it to the county lieutenants’ judgment based on their knowledge of the country if they deemed it expedient. Dunmore added that erecting the new fort and maintaining communications between it and Fort Pitt, now called Fort Dunmore, would offer better protection to area settlers and “awe the Indians.”38

Finally, Dunmore relied on the “Zeal and discretion” of the county lieutenants “to provide the extraordinary means for any extraordinary occasions that might arise.” Ordinarily these officers could not order their men into active service on their own authority except to repel an invasion, or order them—particularly drafted men—to march out of the colony, or more than five miles past the most distant settlements on the frontier. However, Dunmore indicated that if the military circumstances justified doing so, and they could enlist a sufficient number of volunteers, militia officers could conduct operations beyond the limits allowed by law. If they could pursue invading war parties out of Virginia or attack their camps in Indian country, for example, Dunmore encouraged them to take the opportunity to deliver such a stroke. He reasoned that if decisive in stopping Indian depredations, that would certainly justify their actions with the government and “oblige the Assembly to indemnify,” or pay them for their service.39

After issuing his instructions to the county lieutenants, Dunmore wrote to the commander in chief of His Majesty’s force in North America, General Gage, who had just arrived in Boston from home leave in England. The reports from Governor Penn notwithstanding, Dunmore took the opportunity to apprise the general of the situation from the Virginia perspective. His forces had rebuilt Fort Pitt to protect the settlers in the region, “and put it in better condition than it ever was,” at least as a defense against small arms. Dunmore said that when those responsible had completed the task, “They have done me the Honor of calling it by my name.” With all the nations and tribes to the south and west potentially joined in an alliance against Virginia, Dunmore assured Gage that he had the least doubt his colony’s soldiers would soon give a good account of themselves, his earlier comment doubting they were equal to the task notwithstanding. If the few skirmishes that they already had gave any indication of the ultimate outcome, even where the Indians had at least twice the number of men on the field, Dunmore proudly stated, “our people have always kept their ground.”40

Virginia prepared for war on the frontier even as the people in more-protected counties and those in other colonies discussed the deepening constitutional crisis. While the expiration of the Militia Law did not disband the militia, it complicated the means by which the colony paid for military expenses until the General Assembly reconvened. The next several months would determine whether the militia of Virginia’s frontier counties proved equal to the challenge it now faced.

WHEN THE colony needed soldiers, such as for offensive expeditions or the garrisons of frontier forts, the governor would issue a call for troops drawn from the militia to perform actual service in the colony’s pay. Addressed to one or more county lieutenants, the call either stated a given number of soldiers, or proportion of his total, such as “one for every twentieth man,” to be detached for “immediate service.”41 During the French and Indian War, the House of Burgesses appropriated funds for “Encouragement of militia to go out freely for the defence of the country in all times of danger; with a certain assurance of being paid for their services.” Voluntary enlistments were always preferred and sought first. If enough men did not volunteer, the law allowed for drafting men to make up any shortfall. In addition to pay, volunteers and drafted men were promised medical care for illnesses and injuries incurred while on duty, pensions for disabilities that prevented them from earning a living wage after their terms of service expired, and relief for their widows and orphans if they died as a result of service.42 Ordinarily, the governor sought the assembly’s support in appropriating money for soldier pay before issuing the call for men, but he could act without it, albeit in emergencies.

Although written for obtaining recruits to fill the ranks of the standing forces during the French and Indian War, the March 1756 act for frontier defense outlined one method for conducting a draft.43 The law authorized the chief militia officer to summon the field officers and captains commanding companies of the county or borough to a council of war to implement the draft procedure. The captains brought and delivered lists, derived from court records, of all single free white men living in the precincts that made up their respective company catchments, as well as the company muster rolls showing the names of all those enrolled and participating in the militia. After comparing the documents, the officers added the names of any nonexempt able-bodied men residing in their companies’ areas who had not been duly “inlisted and enrolled, according to the militia laws.” The county lieutenant then selected a day and time, and called a general muster at the courthouse. Militia and civil officers spread the word by giving public notice, advertising in the Virginia Gazette, and posting broadside announcements “at all places of public resort.”44

The men assembled in their companies outside the courthouse on the appointed day. After roll call, the captains asked volunteers to step forward and took their names. The county lieutenant then reconvened the council of war inside, where the officers prepared a number of blank pieces of paper, one for each available man in the county. The officers then wrote the words, “This obliges me immediately to enter his majesty’s service,” on the quantity of sheets that reflected the county’s quota. After withdrawing one marked paper for each man who volunteered, those who were absent from the muster became the “first pricked down” and “declared to be soldiers duly inlisted in his majesty’s service” unless later excused. The remaining sheets were put into a box, “well shaken and the papers therein mixed,” and placed in view of all the members of the council of war.

The officers then instructed the assembled men, minus the volunteers, to come forward one at a time to draw one piece of paper from out of the box. As he did so, each man held his paper to “public view.” Anyone who displayed a sheet with the writing was “deemed and taken to be an enlisted soldier.” The officers could excuse a drafted man if someone present who had not drawn a marked paper chose to take his place. A drafted man could also find an able-bodied man who was not drafted but willing to serve in his stead in return for a payment of money.45

Officers received commissions of rank based on the required strength of the units they were to command and were expected to exert their leadership skills and powers of persuasion to recruit a sufficient number of volunteers from a specific administrative company’s catchment. Depending on the number of troops required, more than one complement of company officers may have been allowed to recruit from the same catchment. The county lieutenants and their subordinate field officers and commanders took care not to create organizations that proved too top heavy and therefore inordinately costlier by having individuals serve in higher rank positions than was commensurate with the size of the force actually recruited. The law specified that the county lieutenants could “not depute any greater number of inferior officers . . . than one captain, one lieutenant, one ensign, three sergeants or corporals, and one drummer for every fifty soldiers,” and in like proportions for greater numbers, in a company of foot.46

If the full establishment strength of fifty men for an operational (as distinguished from the administrative) infantry company could not be reached, the number and ranks of the leaders decreased proportionally. A company of foot that consisted of thirty men could not have more than one lieutenant, one ensign, and two sergeants, while a company of fifteen or fewer men required not more than one ensign and one sergeant. Before being taken into pay, the names and numbers on the muster rolls had to be certified by every commanding officer and “attested upon oath” before a justice of the peace of the county where the company had been raised. While they may have been addressed by the titles of higher ranks held in their administrative militia postings, officers received only the pay granted for the ranks approved by the assembly for the command of units on campaign. Commanders who claimed greater numbers of men in order to receive higher rank with corresponding pay, or who appointed more subordinate officers than the actual strength of the unit allowed, faced fines equal to the pay of such “supernumerary officers.”47

When the colony called the militia to active duty in wartime or other emergency, the district adjutants general or expedition commanders—or county lieutenants if all units came from one jurisdiction—usually established rendezvous camps for organizing and training the force that would take the field. The rendezvous camp represented an important step in the process of preparing militia for active service and campaigning, as well as raising provincial regulars when the General Assembly authorized the establishment of standing forces. While a soldier received a modicum of training through the quarterly local company and annual general county-wide musters, what he received at the rendezvous camp improved on that base and helped transform the ad hoc companies into more-cohesive tactical units better prepared for the sustained operations in which they would participate.

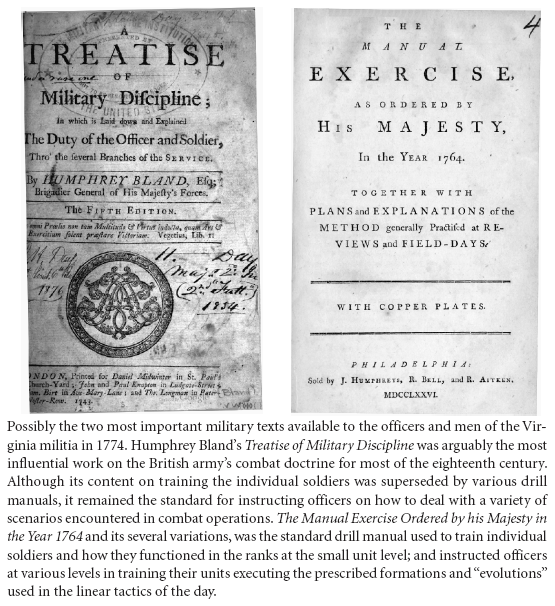

As the Frontier Department’s adjutant general, twenty-one-year-old Major George Washington conducted the rendezvous camp at Winchester for the first militia companies embodied for provincial service in 1754. The training received at other rendezvous camps may have resembled that which then-Colonel Washington directed the officers of the 1st Virginia Regiment to institute when he assumed command in 1755. It included drilling the men in the manual exercise and conventional linear tactics as well as in the “Indian Method of fighting” and practice “Shooting at Targets.”48 Not neglecting officer training, Washington noted that “there ought to be a time appropriated to attain this knowledge” and insisted that they read and apply the lessons found in “Bland’s and other treatises which will give the wished for information.”49

While the men trained in the school of the soldier according to the 1764 drill manual, officers studied Lieutenant General Humphrey Bland’s Treatise of Military Discipline, in which he laid down and explained the duty of the officer and soldier. First published in 1727, its nine editions became what was arguably the most widely read and authoritative work on British army tactical operations and unit leadership for much of the eighteenth century. Based on experience gained on European battlefields but adaptable to those in North America, the treatise provided a valuable instructional text for regular and militia officers alike. Its pages contained valuable maxims and explanations for officers learning or practicing tactics in chapters with such descriptive titles as “General rules for Battalions of Foot, when they engage in the line,” and “for the marching of a Battalion, or a Detachment of men, where there is a possibility of meeting the enemy.” Lessons conveyed in the latter were particularly suited to the fluid environment of petite guerre and fighting partisans in “enclosed or woody country.”50 Although the treatise was developed based on experience gained in or observing operations against the skulking tactics of the irregulars found in European armies, British and colonial American officers found that many methods it espoused were adaptable to the terrain and enemy of North America. Bland’s instructions were not simply followed as written; officers in America combined regular with irregular tactics and blended them with techniques learned from native allies and adversaries and gained from experience in earlier conflicts.

Fighting in the American wilderness required soldiers to use new and diverse methods, skills, and techniques that combined those used in Europe with those found in North America. Using flank guards for marching columns and commanders having their men take advantage of the cover offered by trees, logs, and rocks when attacked by a concealed enemy represents such a combination of both, not the demonstrated superiority of one method over the other. The use of skirmishing tactics in which detachments moving in open order sought to initiate contact with an unseen enemy with a series of small firefights provides yet another example of blended tactics. Skirmishing offered a means of locating and drawing an enemy force into battle where the superior fire of cohesive units determined the outcome of a general engagement.51

When they used the term “Indian Method of fighting,” Washington and other colonial officers did not mean that they simply copied the tactics and techniques of native warriors but developed and employed a new method of bush fighting that emphasized skirmishing. Operations were usually characterized by acting on the strategic offense and the tactical defense, and applied the same principle on a smaller scale at the tactical level of an engagement. The new method placed an importance on light troops and taking advantage of natural cover and concealment. It also continued to emphasize unit cohesion and fire superiority, although not necessarily by fighting in compact ranks and firing in volleys. During the French and Indian War, for example, light troops on scouting and flanking missions ordinarily employed defensive tactics in battle situations. Although their tactics may have at times appeared similar to those of their Indian opponents, they sought to draw the enemy into a fight so that the main force could bring its firepower to bear with the most effect.52

In addition to what they received at musters, the men trained and rehearsed these blended tactics before they conducted an operation. Chaplain Thomas Barton described such an exercise conducted by the provincial regiment in which he served during the French and Indian War that may have resembled the training Washington prescribed for Virginia troops, or that which was conducted at a quarterly general muster or rendezvous camp for militia preparing for campaign:

[T]he Troops are led to the Field as usual, & exercis’d in this Manner—Viz.—They [the columns] are to, and distant from, each other about 50 Yards: After marching some distance in this Position, they fall into one Rank entire forming a Line of Battle with great Ease & Expedition. The 2 Front-Men of each Column stand fast, & the 2 Next split equally to Right & Left, & so continue alternately till the whole Line is form’d. They are then divided into Platoons, each Platoon consisting of 20 Men, & fire 3 Rounds; the right-Hand Man of each Platoon beginning the Fire, and then the left-Hand Man: & so on Right and Left alternately till the Fire ends in the Center: Before it reaches this Place, the Right & Left are ready again. And by this Means an incessant Fire kept up. When they fir’d six Rounds in this manner they make a [sham] Pursuit with Shrieks & Halloos in the Indian Way, but falling into much Confusion; they are again drawn up into Line of Battle, & fire 3 Rounds as before; After this each Battalion marches in order to Camp.53

The Virginia militia had its unique units and individual specialists. In wartime and periods of increased tensions between settlers and Indians, county lieutenants and local commanders in the backcountry engaged certain individuals as scouts and spies. When the General Assembly provided the authorization and means, they also raised detachments or companies of rangers to better defend the frontier. While all three services sought to accomplish related objectives, and the skills and techniques required of individuals engaged in each may in some cases have appeared the same or similar, rangers, scouts, and spies differed in several ways.

During Queen Anne’s War, for example, the government at Williamsburg authorized county lieutenants responsible for frontier defense to raise detachments to “range”—or patrol— the “large vast uninhabited grounds and woods” between settlements.54 Once posted, these early rangers patrolled the areas between forts and fortified houses—known as stations—on horseback to “observe, perform and keep such orders and in their several rangings and marchings” to detect approaching war parties, or pursue and punish marauders who killed or captured inhabitants at isolated homesteads.55 Rangers routinely rode in pairs, or “two together,” with two such teams covering a chain of four posts from opposite ends. With instructions to meet at an appointed time and place at or near the midpoint, they would exchange information, “report their observations, and when necessary . . . carry information on the appearance of the enemy to the nearest stations” so the militia could respond appropriately to a threat.56

When he organized his county’s rangers during Queen Anne’s and King George’s Wars, the chief militia officer appointed a lieutenant to command the detachment. The lieutenant would “choose out and list” eleven able-bodied men who resided conveniently near the frontier station where they were to be posted, and they would report with their own horses, as well as the arms, ammunition, and accoutrement the law required them to keep at home. If the detachment commander could not enlist a sufficient number of volunteers to complete his unit, the county lieutenant drafted the rest from among the enrolled militia. Once formed, ranger units operated only within their home counties. The commander and every ranger received compensation that included pay, based one year of service, plus a stipend for using his own horse and other personal property, that came from the public levy collected in the county. For “greater encouragement” of the ranging service, the General Assembly declared all officers and rangers “free and exempted” from paying county and parish levies and excused from attendance at scheduled musters.57

Through an act of the General Assembly, Virginia called rangers to defend the frontier again in May 1755, during the French and Indian War. The county lieutenants of Frederick, Hampshire, and Augusta Counties were each directed to raise one company of fifty men plus officers, organized to operate on foot, from their respective militias.58 Paid from the provincial treasury instead of county levies, the three ranging companies could be deployed to conduct operations anywhere in the colony the governor directed. During their one-year term of service, rangers answered the immediate orders of the county lieutenant in whose jurisdiction they were assigned and cooperated with companies of the Virginia Regiment—if posted nearby—and units of local militia.59 Although considered part of the province’s standing forces, rangers remained subject to the militia law for discipline and could not be sent out of the colony or conduct missions more than five miles beyond the most distant settlements on the frontier unless authorized by the General Assembly. Conversely, rangers could not be incorporated with British regulars, placed under command of a British officer, or subjected to the Articles of War.60 Over the course of the conflict, the service increased to six companies and included postings to defend the colony’s southwestern frontier. While the governing legislation eventually raised the authorized strength to one hundred men plus officers, ranger companies never achieved the full establishment.61

Whereas a unit of rangers would seek to intercept and engage an enemy war party as well as provide early warning, scouts worked in small independent detachments of two or three men to gather intelligence. Those who supported military operations went ahead of their units to conduct area reconnaissance and surveillance and provided their commanders with information on enemy forces and activities as well as terrain they were likely to encounter. Other scouts were employed closer to home. They also conducted area reconnaissance but paid special close attention to trails and other avenues of approach that led to backcountry communities. Once they obtained information, the scouts returned to a nearby post to report to an officer of the militia and provide early warning of an attack.

Alexander Scott Withers, an early chronicler of frontier warfare, described those who typically volunteered for duty as rangers and scouts as men who “made their abode in the dense forest” and spent most of their time hunting, an occupation he described as “mimicry of war.” Such men were adept at fighting in the wilderness and especially knew how to resist Indian attacks and retaliate in kind. Withers believed the same skills that enabled the hunter to approach the “watchful deer in his lair” allowed the ranger or scout to avoid an Indian ambush and frequently defeat those who waited in the ambuscade. The chronicler believed that the long hunters’ knowledge and the ease with which they moved about the woods to any location among the settlements to warn the inhabitants of danger made them invaluable to the defense of the backcountry communities.62

The spy was neither ranger nor scout—nor even a soldier. More accurately described as a long-range scout in this context, Samuel Johnson’s dictionary defined “spy” as “one who watches another’s motions” by attempting to “search” or “discover at a distance.”63 Spies did not operate in companies or detachments under the command of commissioned officers but worked individually or in pairs. Certain men, such as William Smith of Augusta County, volunteered to serve as Indian spies. Traveling beyond the limits of settlement and often in the vicinity of Indian towns, they ventured though trackless forests to observe the enemy and his activities in his own country. Despite the hazards, Smith explained that he preferred “this employment” to service in the militia.64 Although enrolled in the militia, spies were not considered to be in service and were excused from attending musters without suffering fines.

The Virginia militia provided the colony with a force capable of defending its borders as well as taking the fight to an enemy’s home territory. It was organized and trained to fight by degrees. At the lowest level, local companies responded to alarms that effected the immediate or neighboring communities. As danger increased, the county lieutenant activated the county’s force for its own defense or to assist an adjacent community. The provincial government could call the militia into actual service to repel invasions by external enemies or suppress insurrections and other internal threats. As the likelihood of an Indian war along the Ohio increased in 1774, the militia became more active at each of its levels.