CHAPTER 7

The Drums Beat Up Again

Partial Mobilization Becomes General

July 1774

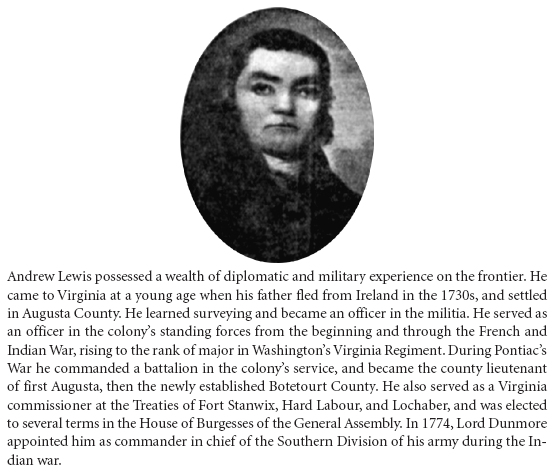

ALTHOUGH THE Cherokee chiefs had promised not to go to war against Virginia, Shawnee and Mingo war parties roamed in search of vulnerable settlements. Messengers carrying the alarms—whether reporting actual depredations, circulating rumors of an attack, or repeating someone’s claim to have sighted Indians—helped to spread fear and panic in communities throughout the region. The county lieutenants reported to Governor Dunmore that “skulking parties of Indians (believed to be Shawanese and Delawares) had been discovered lately among the Settlements” in Augusta, Botetourt, and Fincastle Counties, with some of them venturing within twenty-five miles of Botetourt Courthouse.1 In one attack, Colonel Andrew Lewis of Botetourt County reported that Shawnees had attacked “a Body of men” near his Richfield plantation home, not far from the courthouse town of Fincastle, killing one man and wounding another.2

More people continued to shelter in forts throughout Augusta County after the Indian attacks became more “troublesome.” On entering active service, Benjamin Cleaver was appointed as a sergeant and detailed with others to guard the “forts of and Frontiers of Tigers [Tygert] Valley,” a branch of the Monongahela, for a term of four or five months.3 Exercising such caution was not misplaced. Indian warriors operating about the neighborhood of Warm Springs shot and slightly wounded one William McFarlon (or McFarland) during the first week of July. The otherwise minor incident nonetheless sent local inhabitants rushing “in ye Greatest Confusion” for the protection of nearby forts. In an attempt to counter the threat and put a stop to their intended hostilities, Colonel Charles Lewis ordered out several companies of Augusta County militia. One of them engaged a group of Indian warriors near the headwaters of the Monongahela. Captain John Wilson was wounded by “a Shot in his Body,” which everyone hoped would not prove mortal; the soldiers he commanded killed three warriors in the encounter.4

The county lieutenants ordered the captains commanding companies to send out scouts to watch the warrior paths and rangers to rigorously patrol the approaches to settlements in order to detect and provide early warning before enemy raiders struck. Due to their vulnerability to attack along the frontier, the colonels also instructed the captains to send messengers to isolated settlements to warn the inhabitants that a war had begun and to advise them to remove their families to more secure locations.5

After dispatching scouts and patrols from his company, Captain John Stuart of Botetourt County sent an express to warn the settlers living in the farthest and most isolated settlements along the Great Kanawha River. Most of them heeded the warning. John Jones, for example, felt “compelled by the incessant incursions of the Indians to take refuge among the inhabitants” of the Greenbrier area. He then volunteered to serve in the company under the command of Captain Matthew Arbuckle to build and garrison a fort on Muddy Creek that would “guard the inhabitants against the incursions of the Indians.”6

Walter Kelly had a different response. Stuart described Kelly as having a “bold and intrepid disposition” but suspected that he “might be a fugitive from the back parts of South Carolina” who had established his habitation about twelve miles below the great falls of the Kanawha near the mouth of Kelly Creek. When Stuart’s messenger arrived at Kelly’s cabin, he also found fifty-year-old John Field, the colonel of the militia from neighboring Culpeper County. Accompanied by “several neighbors and one or two Negroes,” Field had come to survey the claim on the military grant he received for his service as a captain in the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War.7

Kelly “received the intelligence with caution” and immediately decided to send his wife and daughter, along with his livestock, to Greenbrier in the care of his younger brother, William. Stuart described William Kelly as a young man of equally suspicious character. While the others prepared to evacuate, Field expressed different ideas. “Trusting his own Consequence and better knowledge of publick Facts,” he persuaded the older Kelly brother to stay. He argued that “[n]othing of the kind” had been heard before and evaluated the new intelligence as “not worth noticing.” Although Walter sent his family to safety, he decided to remain on his farm with Field, an unidentified male described only as a “young Scotchman,” and a young slave woman.

Later in the day, while Kelly and Field worked at the tanning trough, a party of Indians closed in on the cluster of buildings. As the two men carried some leather toward the cabin, the raiders opened fire and yelled their war whoops. As they ran toward the house to get the muskets kept inside so they could fight back, Field noticed that Kelly had fallen to the ground dead. When he got closer to the house, Field remembered that they had “not charged”—or loaded— either musket, which rendered them useless. Meanwhile, the warriors neared the cabin where “the Negro girl and Scotch boy [were] crying at the door.” Realizing the futility of keeping on that course, the unarmed colonel ran out into the adjacent cornfield. He used the concealment provided by the tall stalks to evade any pursuers and avoided capture or death to make his escape. When Field paused to catch his breath, he looked back toward the house and watched helplessly as the warriors killed the boy, scalped both him and Walter Kelly, and carried the girl off as their captive.8

When William Kelly and his party arrived safely in Greenbrier, he told Stuart that they had gone some miles from the farm when they heard gunfire. Kelly confided to Stuart that he “expected his brother and Field had been killed.” Stuart gathered ten or fifteen volunteers from his company and went to see “what was the consequence” and possibly rescue any survivors. When the patrol met Field coming from the opposite direction, he was naked except for his shirt, his limbs were grievously lacerated from passing through “briars and brush,” and he was visibly worn down with fatigue and cold. The exhausted veteran informed the soldiers of the raid, his escape, and the fate of his late companions. Stuart led his men back to Greenbrier to defend the settlement if the Indian raiders chose to penetrate further into Botetourt County.9

Writing to Colonel Preston, his Fincastle County counterpart, Colonel Charles Lewis expressed his hope that when the General Assembly convened in August with the newly elected burgesses, they would find some means of ending the war. He did not know that by the time his report on the incident near Warm Springs reached Williamsburg, the governor had already dissolved the assembly, pending new elections. Nor did Lewis know that Dunmore had also departed the capital on Sunday, July 10, to see the situation on the frontier firsthand. He sought to determine the cause of the recent disturbance and, if possible, find a means to settle matters amicably at a conference with the different nations of Indians involved.10

DESPITE THE events that transpired elsewhere on the frontier, the Pennsylvania officials in the area surrounding Pittsburgh continued to view the looming Indian war as a crisis instigated by Virginia for its own benefit. In correspondence with Governor Penn, Arthur St. Clair, Aeneas Mackay, Devereux Smith, and Joseph Spear asserted their conclusions that “the Crew about Fort Pitt (now Fort Dunmore) are intent on a war.” They charged that John Connolly had express riders constantly on the road between Pittsburgh and Williamsburg with reports that gave the Virginia governor “a flagrant Misrepresentation of Indian Affairs,” designed to influence his decisions in that direction.11 In an attempt to curry favor so the Ohio-area Indians would not view Pennsylvania in the same light as Virginia, St. Clair had Croghan “collect a small present of goods.” He then told the retired Indian deputy superintendent to distribute the gifts as a condolence to the Delawares, Shawnees, and Mingoes—the three nations most affected by the recent violence. He instructed Croghan to attribute the gifts to the orders of the generous Pennsylvania governor. St. Clair confided, “Whatever may be Mr. Croghan’s real views” on the border controversy, “he is hearty in promoting the general tranquility of the Country [and] . . . indefatigable in endeavoring to make up the breaches” to prevent an Indian war.12

In order to quiet the intercolonial dispute so they could focus attention on the troubles with the Indians, Lord Dunmore ordered Connolly to discuss settling a temporary boundary with St. Clair and the Westmoreland magistrates. Although the governor still described the Pennsylvania government’s demands as “so extravagant he could do nothing with them,” he authorized Connolly to propose a line of jurisdiction ten or twelve miles east of Pittsburgh. Knowing the captain’s abrasive demeanor often proved counterproductive, the governor further admonished Connolly to give those acting under Pennsylvania authority no just reason to take offense.13

Connolly’s nature would not allow him to evade controversy. On June 25, twenty-seven individuals signed a petition that protested the “arbitrary proceedings” of Connolly’s “Tyrannical Government” and sent it to Philadelphia “On behalf of themselves and the remaining few inhabitants of Pittsburgh who have adhered to the Government of Pennsylvania.” The petitioners listed their complaints about the treatment their colony’s partisans received and urged Governor Penn to take some action to relieve their distress. In addition, they blamed the “present Calamity & Dread” of frontier war entirely on Connolly’s “unprecedented Conduct.” Despite the efforts of Pennsylvania authorities to maintain good relations with “our friendly Indians,” the petitioners stood convinced of the Virginians’ intent to force a war on them.14

The subscribers attached a litany of Connolly’s lawless acts to their petition. The list recounted examples of Connolly’s disdain for Pennsylvania law and authority, such as his surrounding the Westmoreland County courthouse at Hanna’s Town with an armed force of two hundred men. They drew the governor’s attention to Connolly’s attempted interference with the proprietary colony’s dominance of commerce with the Ohio tribes and cited Michael Cresap’s attack on the Indians employed by the trader William Butler. Finally, they had had enough of Connolly using the Virginia civil and military force at his command to run roughshod over those who remained loyal to Pennsylvania’s government. To reinforce these complaints, the petitioners reminded the governor of the several incidents of assault and resulting physical injuries, as well as the destruction of livestock and vandalism or arson of homes and other property directed against them and their families. Many of these incidents also exemplified Connolly’s vindictiveness, as they followed the reprimand he received from Dunmore for the unjustified arrest and incarceration of Westmoreland magistrates Mackay, Smith, and McFarlane.15

The question of trade as another point of contention between the two colonies went beyond the interference mentioned in the petition. St. Clair expressed his concern to Penn that the Virginians had “determined to put a stop to the Indian Trade with this Province.” He learned that Connolly and some associates had received an exclusive privilege to conduct business with the tribes and had imposed a duty of four pence per skin, payable to Virginia, on all traders shipping pelts from Pittsburgh. Furthermore, Connolly had previously sent Captain Henry Hoagland with a company of militiamen across to the north bank of the Ohio to intercept any Pennsylvania traders returning from Indian country. Although they had orders only to stop and examine them, Mackay alleged the soldiers had orders to treat “as Savages & Enemies, every Trader” they found in the woods about Pittsburgh, and kill them.16

While patrolling “about four miles Beyond Big Beaver Creek” on July 5, Sergeant Alexander Steele’s twenty-man detachment encountered William Wilson with his party of traders and Indian escorts “bringing up a quantity of skins” from the direction of Newcomer’s Town. The sergeant halted them and asked Wilson if he employed any Shawnees. The trader replied that he did not and identified his escorts as Delawares. Steele explained that he had orders to conduct the entire party, whites as well as Indians, with their packhorses and skins, to the mouth of the Little Beaver for his commander to examine. Although Wilson later told St. Clair that Hoagland threatened to kill the Indians regardless of nation, the captain released them in the morning after the trader gave his bond for £500 to satisfy Connolly.17

The recent petition indicated that the divide between the partisans of the colonies continued to widen, with those in Virginia’s interest apparently gaining an advantage. According to Mackay, “the Friends of Pennsylvania” had determined to abandon Pittsburgh and erect a stockade “somewhere lower down the Road” to secure their cattle and other property until they could better determine the direction future events would take. Some Pennsylvanians even proposed erecting a new traders’ town at Kittanning that would replace Pittsburgh as the center of their colony’s commercial influence in the region.18 St. Clair and his fellow magistrates also decided to maintain the Westmoreland County ranging company in service for at least another month and, if possible, until after harvest time, in order to assist and protect the people of Pennsylvania. Although they had pledged to raise the money themselves, they applied to the governor, seeking relief from the financial burden.19

Alexander McKee, the Indian Department deputy superintendent, called representatives from both colonies to meet on June 29 to hear the latest news from Indian country. Captain White Eyes had just returned from the most recent gathering of Ohio Indian leaders at Newcomer’s Town. As the colonial leaders had requested, the Delaware chief dutifully delivered their message to the several assembled nations “to hold fast the Chain of Friendship subsisting between the English and them,” despite the disturbances that had happened “between your foolish People and theirs.” He reported that the Shawnee headmen had met in a council of their own at Wakatomika and said that they intended to send their “King” to Fort Pitt to hear what the British had to say. According to Aeneas Mackay, White Eyes gave the Pennsylvanians the strongest assurances of their friendship from not only the Delawares, Wyandots, and Cherokees, but the Shawnees as well.20 At the conclusion of the meeting, the Delaware emissary returned to Newcomer’s Town with the speeches the colonial leaders wanted him to deliver in an attempt to end the killing.

Following the council’s adjournment, St. Clair initially expressed optimism that “Affairs have so peaceable an Aspect,” but after he heard that a large body of Virginian troops was in motion, he feared it would jeopardize the chances for peace. The Westmoreland magistrates soon expressed a new concern from the Pennsylvania perspective when they heard that Dunmore had lately commissioned three new captains, including Cresap, to raise and lead companies of rangers for frontier defense. Even the president of the Westmoreland County court, Captain William Crawford, accepted a commission and “seems to be the most active” among the Virginia officers. After noting that he had recently marched down the Ohio toward Wheeling in command of a body of troops on his second expedition, the judgmental St. Clair added, “I don’t know how Gentlemen account these things to themselves.”21 Privates Evan Morgan and David Gamble could have answered him. Morgan enlisted in Captain Zackquill Morgan’s company for the expedition when he “arrived at age, animated with a desire to repel their [the Indians’] inroads— avenge his murdered neighbors—and prevent further invasions.” Similarly, Gamble “volunteered at Redstone Old Fort” to serve in Captain Cresap’s company on the expedition “to fight against the Indians.”22

When St. Clair received reports of “four Companies on the march to Pittsburgh,” he expressed his usual skepticism. He knew that Connolly had received Dunmore’s approval to conduct an offensive operation against the hostile Indians at the end of the previous month, but St. Clair doubted his ability to execute it. Assuming that the expiration of Virginia’s Militia Law had restricted that colony’s ability to marshal the necessary resources, he told Governor Penn “it is not an easy Matter to conduct so large a Body thro’ an uninhabited Country where no Magazines are established.”23

The Virginians had approximately eight hundred men in motion for the long-awaited operation and relied on their existing militia and invasion and insurrection laws to obtain the necessary provisions and supplies. Connolly appointed an able officer, Captain Dorsey Pentecost, as the conductor of stores and contractor for the army. As such, it fell to him to furnish all the militia soldiers on active service with supplies and provisions. Connolly also appointed officers to serve as commissaries, like Captain William Harrod. The commissary appropriated the livestock, flour, or other foodstuff from private owners, to whom he issued receipts for the appraised value. The commissary then delivered the provisions to the destination designated by the conductor of stores, such as the fort at Wheeling. After delivery, and obtaining the necessary documentation, the commissary settled the accounts for all the associated expenses—including the active-duty pay for the militia soldiers who drove and escorted the cattle, packhorses, and wagons—with the conductor of stores. When the House of Burgesses convened and appointed the required commission to examine and approve the documentation, those holding valid receipts could submit their claims for reimbursement from the colonial treasury.24

While the documents may not follow the chain of one single requisition, the following series illustrates an example of the process. On July 4, Captain Harrod presented a receipt to Abraham Van Meter for “Three Steers & one Cow,” with a complete description of each animal, appraised for “Sixteen Pounds Ten Shillings” by Jacob Vanmeeter and Edmund Polke “for the Use of the Government of Virginia.” On July 16, Connolly directed Harrod to let Captain Pentecost “have the cattle you bought for Whalin [Wheeling] to be sent down there with all expedition.” On July 20, Pentecost instructed Harrod to “Convey them to the mouth of Wheeling as Quick as Possible & Take an acct. of our Expences, what you gave for them,” and after delivering them “have them appraised and Take care of all the accts. I may be able to Settle with you.” Finally, Captain Crawford, in command at Wheeling, acknowledged receiving “Twenty Fives Beeves for use of the militia at Fort Fincastle” from Harrod on August 2.25

John Montgomery, the Carlisle merchant who procured and sold the powder to St. Clair’s rangers, expressed his optimism that “the storm will blow over, and yet peace and Tranquility will be Restored to the Back Inhabitants.” In a letter, he told the governor that White Eyes’ speech in Pittsburgh at the end of June proved the Delawares were all for peace and that Montgomery expected the Shawnees to follow their lead. Incredibly, Montgomery expected no further trouble from them or the Mingoes. Without citing any evidence to support his claim, the merchant declared that Logan, “now satisfied for the loss of his Relations” with the “Thirteen Scalps and one prisoner” he had taken in June, assuredly “will sit Still until he hears what the Long Knife will say.”26

Montgomery had no sooner expressed this optimism than a war party again terrorized the West Augusta area. Apparently not yet as satisfied for his loss as Montgomery had believed, Logan and seven followers scouted in preparation for their next attack near the mouth of Simpson’s Creek on the West Fork of the Monongahela. After observing William Robinson, Thomas Hellen, and Coleman Brown pulling flax in a field on July 12, the Indians crept up on the unsuspecting farmers as if stalking a group of deer. They opened fire and charged out from the woods. One warrior pounced on Brown as he lay dead and bleeding from multiple gunshot wounds and removed his scalp. Others overwhelmed and subdued Hellen, while the rest ran after Robinson as he attempted to escape. After a short chase, Logan and others caught and restrained him and took him back to where their comrades held Hellen.27

The search of the home and surroundings for additional settlers to kill, scalp, or take captive proved fruitless. When area inhabitants “forted up” during the recent alarm, Robinson had secured his wife and four children at Prickett’s fort, the fortified home of Jacob Prickett, a sergeant and fellow member of Captain Zackquill Morgan’s militia company, near the confluence of the Monongahela River and Prickett’s Creek. Resigned to taking only one scalp and two captives for their effort, the braves headed back toward Indian country. As they secured the prisoners, the English-speaking Logan became friendly and treated Robinson kindly. He assured his captive that if he went back to his town “with a good heart” and did not attempt an escape, he would spare his life and have him adopted into an Indian family. It was not a simple act of mercy, as Logan had plans for his prisoner that exceeded the immediate satisfaction of his vengeance. Throughout the journey to Wakatomika, Logan maintained a diatribe against Cresap in which he vented his intense hatred for the man who had allegedly murdered his family.28

Three days after the incident on the West Fork, John Pollock, David Shelvey, and George Shervor reported that a war party of thirty-five Indians had attacked them and six others as they worked in a corn field on Dunkard Creek. In their deposition to Westmoreland justice of the peace George Wilson, the three testified that although they had escaped, the warriors had killed and “sadly mangled” four of their friends, while two were missing and their fates remained unknown. The men explained that Captain Cresap’s company of rangers gave chase, but the Indian raiders had the insurmountable advantage of a full one-day head start.29

Between giving his approval in June and reaching Winchester a month later, Governor Dunmore expanded the size and scope of the mission to Wheeling that Connolly had proposed. The governor called on the county lieutenants of Frederick, Dunmore, and Berkeley Counties for additional troops and appointed Major Angus McDonald to command an expedition to raid Wakatomika or other Upper Shawnee towns. With a rank more commensurate with the size of the assembling force, the Frederick County officer superseded Captain Crawford as commander, but the latter continued to play a vital role at Fort Fincastle supporting the campaign.30

Crawford had already led two expeditions to the mouth of Wheeling Creek, where his men continued work improving Fort Fincastle. Meanwhile, McDonald departed Winchester with troops raised in Frederick, Berkeley, and Hampshire Counties. Cresap’s and other companies joined the battalion as it marched to Pittsburgh by way of Redstone and continued down the Ohio toward Wheeling. As the Virginia governor had ordered, Colonel Andrew Lewis also began raising an additional one thousand five hundred men for active service to defend the settlements and build a fort at the mouth of the Kanawha.

With troops in motion, war appeared more likely than ever. When the Westmoreland County magistrates heard that Connolly had sent the Indians an inflammatory “Speech,” it confirmed their suspicions. Acting on Dunmore’s orders, the captain commandant demanded that the Shawnees apprehend Logan, his war party, and any warriors of their nation who had “committed murder last winter” and deliver them, as well as all the prisoners they had taken, to Virginia authorities. If they refused, Connolly threatened that the Virginians would “proceed against them with Vigour & will show them no Mercy.”31

On July 19, in the wake of the recent attacks, Connolly and St. Clair entered another debate by writing letters that contrasted their respective colonies’ approaches to the frontier crisis. In his opening volley, Connolly charged that the Pennsylvanians’ naïve reliance on the “pacific dispositions” of the Indians had lulled them “into supineness & neglect” of their own defenses. Such a policy, he said, had tragic consequences, such as the attack of a few days before in which “six unfortunate People were murdered by a Party of thirty-five Indians” at Dunkard Creek. He further warned, “The Country will be sacrificed to their Revenge” if Pennsylvania did not take immediate steps to check the hostile Indians’ “insolent impetuosity.” He asserted that the people of the frontier wanted nothing more than their government’s protection. Connolly concluded that Pennsylvania appeared reluctant, stubborn, and “highly displeasing to all Western Settlers,” while Virginia at least took action to protect its inhabitants. As head of Virginia’s civil government and military establishment in the Pittsburgh region, Connolly had “determined no longer to be a Dupe to their amicable professions” but had decided to “pursue every measure to offend” the Indians, with or without assistance from the “Neighboring Country”— Pennsylvania.32

Three days later, St. Clair countered Connolly by writing that “Such an Effect could never follow from such a Cause.” The Pennsylvanian said that “the great armed force” sent down the Ohio on the pretense that it could effectively protect them had actually created the false sense of security into which Virginia’s people had fallen. St. Clair agreed that their respective governments had to act to prevent depredations by hostile Indians but argued that Pennsylvania’s solution of “ample Reparations . . . for the injuries they had already sustained” would ultimately prove more effective. Only “an honest open intercourse,” he said, could immediately establish and maintain peace in the future. St. Clair then stated his hope that Pennsylvania’s government would “continue to be founded in Justice, whether that be displeasing to the Western Settlers or not.” St. Clair did not see the least probability of a war unless Virginia’s maneuvers up, down, and across the Ohio brought about such an event.33

Although fellow Pennsylvania magistrate Wilson had sent him the deposition, St. Clair gave the reported recent Indian attack no credibility. On the same day that he countered Connolly’s assertions, he informed Penn of the latest occurrences in Westmoreland County. Routinely skeptical of any news about Indian hostility, especially when it originated from or supported the Virginia side, he doubted that “some People were killed upon Dunkard Creek on the 15th instant.” He explained that because such news spreads as quickly as the alarm, and this one had not, he questioned its veracity. He believed the deponents started the rumor in order to allow Cresap an excuse for circumventing Connolly’s orders “not to annoy the Indians.” And although still optimistic that Pennsylvania would escape the “mischiefs of a War,” St. Clair noted that so far, the Indians had evidently aimed all their operations at the Virginians. Nevertheless, he took no chances and distributed “Arms all over the Country in as equal proportions as possible” to better enable Pennsylvania inhabitants to defend themselves. The very next day, as if to underscore Connolly’s argument, David Griffey reported that he saw five Indians, with “Guns over their Shoulders,” on the ridge dividing Brush and Sewickley Creeks, only four miles west of the courthouse. They were armed and obviously not traders, and Griffey described them as ready for battle, “Quite Naked all but their Breechclouts, Marching Towards Hanna’s Town.”34

St. Clair confided a growing uneasiness concerning the Westmoreland rangers. With their second month expiring at a time when the “Country is in such Commotion, and the Harvest not yet in, they cannot be dismiss’d.” Consequently, the Westmoreland gentlemen who pledged their financial support stood to assume the expense when the provincial funding terminated. St. Clair sought the governor’s assurance of seeking yet another means of relieving them of the burden.35 On July 20, the Pennsylvania Colonial Assembly appropriated the money and granted the governor authority to “draw Orders on the Provincial Treasurer for any Sum not exceeding Two Thousand Pounds” for “Paying & Victualing” the rangers until August 10. The assembly agreed to extend the appropriation for the same amount until September 20 if it proved necessary, provided that the strength of the force did not exceed two hundred men. By financing the appropriation with the excise tax imposed on the sale of wine, rum, brandy, and other spirits, and the fines collected for failure to pay the excise taxes on liquor, the assembly justified the expenditure as the means for “removing the Panic” caused by the “late Indian Disturbances” on the frontier, as well as to subsidize the costs associated with efforts to maintain the peace and friendship that subsisted between “this Province and the Indians.”36

In contrast to St. Clair’s skepticism about reports of Indian depredations, Valentine Crawford needed no convincing. He wrote to George Washington that marauding warriors had recently “killed and taken [captive] . . . thirteen people up about the forks of Cheat River,” only about twenty-five miles from his farm on Jacob’s Creek. He expressed his deep concern that local inhabitants had seen “savages prowling” about the Monongahela region and expected them to strike somewhere at any time. With “all the men, except some old ones,” gone “down to the Indian towns” on the expedition, “all their families are flown to the forts.” Two hundred people, mostly women and children from the surrounding area, had taken refuge in Crawford’s fort. To further underscore the differences in attitude between Virginians and Pennsylvanians, Crawford took the position that “standing our ground here depends a good deal on the success of our men who have gone against the savages.”37

AFTER THE late June meeting in Pittsburgh, Captain White Eyes returned to Newcomer’s Town carrying the speeches colonial leaders had given him to deliver to the assembled Indians. On his arrival he learned that, “Contrary to their promise before the Chiefs of the Delawares” at the last council, several Shawnee war parties had set out to attack the Virginia settlers. Those same chiefs now instructed White Eyes to tell the Virginians “it would be to no purpose to Treat further with them [the Shawnees] upon Friendly terms.” The assembled sachems also informed White Eyes that the Shawnees and their Mingo allies had evacuated their Wakatomika towns and relocated to the area of the lower Shawnee towns near the mouth of the Scioto. The neutral Delawares may have said this to keep the Virginians from attacking so close to their own villages in the area and assured them, saying, “if there is yet one Remaining we would Tell you.” They wanted White Eyes to have the Virginians consider crossing the Ohio from the mouth of the Great Kanawha in order to attack their enemies. Otherwise, they feared that Virginia soldiers approaching near the Delaware towns in the area would frighten the women and children and find the “Shawanese are all gone.”

Before leaving the last council at Newcomer’s Town, the leader of one of the Shawnee war parties boasted that after he struck the Virginians, he would “Blaze a Road” to Newcomer’s Town and “do Mischief,” just to see if an actual or only a “Pretended” peace existed between the whites and the Delawares. Another Shawnee chief, Keesmauteta, said that since “his Grandfathers, the Delawares, had thrown his people away,” they expected that according to ancient custom, such hosts had “Always Turn’d about and Struck them” in the back as they departed. The Delaware envoy had also discovered that another Shawnee war party intended to go to Fort Pitt to kill Croghan, McKee, and Guyasuta, and intercept and kill White Eyes and his companions so that they could carry “no more news . . . between the White People and the Indians.” Before leaving to return to Pittsburgh, White Eyes sent a message to the Wabash—or Miami—Indians “not to Listen to the Shawanese” for they only sought “to draw them into Troubles” and fighting a war they did not want.38

As White Eyes headed back to Pittsburgh from Newcomer’s Town, Logan gave the “scalp haloo” outside of Wakatomika on July 18. All the warriors in the town came out to greet the returning party and escorted them and their captives to the council house for trial. In accordance with the ritual, the Indians forced Robinson and Hellen to run the gantlet. Although they received merciless beatings every time they fell, both men survived the ordeal. With each captive tied to a stake before them, the Mingoes debated whether to kill and burn them or to present one or both as a condolence to a grieving family. Keeping his promise, Logan convinced the assembled warriors and elders to spare Robinson’s life. The conquering warrior untied the captive from the post and fastened a wampum belt around him to signify his adoption, and another family adopted Hellen. Logan took his new ward to a cabin and presented him to his aunt. Logan explained to Robinson that the old woman had lost a son in the massacre at Yellow Creek, and he now took his place in the family to make it whole once more. As Robinson looked around, Logan introduced him to some cousins as his new brothers by adoption.39

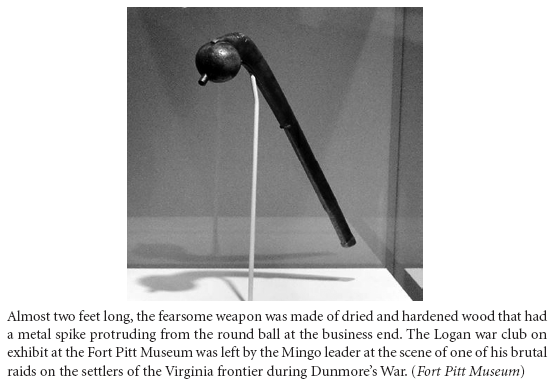

Three days later, Logan brought Robinson a piece of paper and told him he had to write a letter for him; this was the purpose for which Logan had taken him prisoner and ensured his survival. After he mixed gunpowder and water to make ink, the warrior dictated his words. Addressed to Captain Michael Cresap, he asked, “What did you kill my people on Yellow Creek for?” Although white people had killed other relatives at Conestoga “a great while ago [in 1763],” Logan said he “thought nothing of that.” But when Cresap—allegedly—killed his kin on Yellow Creek and took his niece prisoner, the warrior vowed, “I must kill too; and I have been three time[s] to war since.” He then added, “the Indians is not Angry only myself.” Robinson signed it “Captain John Logan” with the date July 21, 1774. The warrior took the note and set out to war again, telling his scribe that he intended to tie it to a war club and leave it in the house of a family he would murder. Throughout his captivity, Robinson vainly assumed Logan would offer to exchange him for the young girl.40

Leaving such a notice by a corpse represented another war ritual common to many Indian nations. Reverend Heckewelder explained that when Indians had decided to take revenge for a murder committed against their people by another nation, they generally tried to make a bold attack to strike terror in their enemies. Sending a war party to penetrate deep, “as far as they can without being discovered,” into the enemy’s country, they would attack and leave a war club near the body of a person they murdered and “make off as quick as possible.” Leaving the war club “purposefully” let the enemy know what nation committed the act so they did not wreak their own vengeance on an innocent tribe. The war club also signified the aggrieved nation’s demand that unless the offending nation took action to discover and punish the “author of the original aggression,” the club represented the means of further avenging the injury and served as a formal declaration of war. “If the supposed enemy is peaceably inclined,” Heckwelder continued, they would send a deputation to the aggrieved nation to offer a suitable apology, which typically blamed “foolish young men” who acted “altogether unauthorized and unwarranted” without the chief’s knowledge. Some suitable condolence presents also accompanied the apology in order to “cover,” or symbolically bury, the dead.41

AS SACHEMS of the Ohio nations met at Newcomer’s Town, Sir William Johnson convened a “Critical Congress” of Six Nations chiefs and leading warriors at his Mohawk valley manor, Johnson Hall. The Indian superintendent promised General Gage to do everything in his power of persuasion to “divert the Storm” gathering on the Ohio. He therefore planned to discuss the violence committed on the frontier and seek the assistance of the Six Nations to “bring the troublesome Tribes about the Ohio, Ouabach [Wabash], &, ca. to make amends.” The Iroquois realized that the Shawnees’ own actions had largely led to the disorders and caused trouble among their confederacy’s members, especially alienating many Mingoes. But as they and Johnson knew, although not an excuse, a “lawless Banditti” of white settlers who had “surprised, & Murdered near 30 Indians, partly Shawanese, but principally of the Six Nations [Mingoes],” bore some of the blame as well.42

Johnson first had to convince the Iroquois Confederacy’s leaders to help “preserve the peace & cooperate” with the Indian Department. Together they could also stop the “irregularities & Murders” and “remedy the abuses” of which the Indians often complained. Simultaneously, they had to curtail the “Artifices of the Shawanese and others” who sought to forge alliances and engage the rest of the Indians of the area, as well as draw the Iroquois themselves, into the smoldering war on the Ohio. After much negotiation, Johnson managed to “withdraw the 6 Nations from among them” and concluded a treaty that kept the Iroquois, including the dependents of their confederacy, from assisting the Shawnees.43

On the verge of one of his greatest accomplishments as His Majesty’s superintendent of Indian affairs for the Northern Department, Johnson became “seized of a suffocation” after a particular strenuous day of negotiating and died of a stroke at 8:00 in the evening on July 11. The next day, Colonel Guy Johnson, William Johnson’s nephew as well as son-in-law, sent an express to inform General Gage of his uncle’s passing, but even to his last breath, his final efforts had kept the war on the Ohio from spreading. The conference observed a recess for the funeral. Two thousand mourners, including a number of Crown and colonial officials, and an impressive array of Indian leaders attended. The latter, representing many nations and tribes, paid their last respects to the white man they arguably trusted most. Colonel Johnson assumed the interim superintendence until the Crown appointed a permanent successor. Since Indian leaders already recognized him as such, he took over the conference. Five days after William Johnson’s death, July 16, Guy Johnson brought the congress to an “agreeable Termination.”44

The representative sachems who constituted the central council of the Six Nations, which usually met at Onondaga, agreed to help “defeat the projects of the Shawanese and their Adherents” by exercising its dominion or influence over other nations. If necessary, they would “proceed to Extremities” against any that considered an alliance with, or supported, “the measures and designs of the Shawanese” and their allies. Cognizant that the Shawnees would attempt to convince others that the appeal to unite all of them in a general alliance against the British had originated in Onondaga, the council dispatched several deputies to articulate the confederacy’s actual position. Carrying wampum that affirmed the message, the deputies warned that any nation or tribe that joined with the Shawnees would face severe consequences. The deputies assured them that all who “acted with Fidelity during the present Troubles” would receive the confederacy’s support in reward. Guyasuta, the Six Nations viceroy in the Ohio area, received “private instructions” to “divert other Tribes” and isolate the Shawnees from any potential allies.45

In his earlier correspondence asking William Johnson to use his “Interposition with the 6 Nations as Moderators” to prevent a general Indian war, Governor Penn had succeeded giving the old and new Indian superintendents his view of the situation, albeit from his colony’s perspective. The Pennsylvania governor’s one-sided account of the “distress” on the frontier stated, “Tho in so many Instances aggressors,” the Virginians “chuse to consider themselves as the persons injured.” The resulting war, he said, would only provide them the pretext to take the opportunity to cross the Ohio and take possession of the “Country even beyond the Limits of purchase” negotiated with the Six Nations at Fort Stanwix in 1768. That made preventing a general war more complicated, since the Indians who were not a party to the treaty could find common cause and join an alliance with the Shawnees. Because he knew it had long been the plan of some Ohio Indians, including some of their Mingo emigrants, to challenge Six Nations suzerainty, Johnson believed it imperative for the Crown to immediately address the Indians’ grievances.46

Seeking to exercise the leverage that had long benefited the Crown because of their alliance, Johnson urged the Six Nations to immediately express their vehement disapproval of the Shawnees’ actions and demand they cease committing all such cruelties against the settlers. Otherwise, he warned, their “Reputation as a powerful Confederacy will greatly suffer in the Eyes of the English.” The Six Nations agreed to “check the incursions by their dependents who run about like drunken men and ought to be disarmed by those who are sober.” If the Iroquois could not control their people on the Ohio, Colonel Johnson warned, “the English should be obliged to raise their powerful arm against them, which might have dreadful consequences.” 47

DESPITE THE reduced tensions with the Cherokees, rumors of and actual Indian sightings still ran rampant, and Captain William Russell reminded Colonel Preston that Fincastle County inhabitants remained vulnerable to “a Stroke from the Northward [Shawnee] Indians.” Captain James Robertson (not the emissary to Chota of the same name) reported that the men of his company had discovered an Indian camp on Paint Creek, and he and Captain Joseph Cloyd had stopped at the Culbertson’s Bottom settlement waiting for more men before proceeding. When Colonel Christian learned that local militia had reported seeing “Indian signs” indicating the presence of from fifty to three hundred warriors near their communities, Major Arthur Campbell recommended the rangers not attempt a “long March” beyond the settlements into Indian country until supplied with additional ammunition. Although he had recently received twenty-five pounds of gunpowder, Christian knew that he needed more for the ranger and local militia companies to meet likely contingencies. Christian further recommended that if the county needed additional men, Preston should have the captains of the three “lower Companies” detach them. He knew that between the companies under the command of Captains William Cocke and Evan Shelby, they could easily detach fifty men without putting the security of their own communities at risk. In addition, Christian decided not to order the rangers to advance through Moccasin Gap in the Clinch Mountains as planned. Under the new circumstances, such a move would leave an avenue of approach open by which an Indian war party could advance along Sandy Creek without being detected.48

Instead, he assigned a different sector to each company in order to cover the approaches to the settlements, provide mutual support, and reinforce the local militias defending their communities. Remaining active and vigilant, each company could detect a war party moving through its assigned area and either move to “way lay or follow the enemy” and engage them from front or rear. If the Indians managed to strike a settlement before the company could disrupt their scheme, the rangers could pursue them. Christian posted Captain Crockett’s company at the head of Sandy Creek with orders to range from there “about the head of the Clinch & Blue Stone” and stand ready to assist the militia guarding the Reed Creek and “head of Holston people” from attack. He further instructed Crockett to keep his men “ready at an hours warning” should it prove necessary for them to go to the aid of the New River communities. Captain William Campbell’s company marched to cover the settlements on the lower Clinch and near Long Island on Holston and return through Moccasin Gap and back up the Clinch to rendezvous with Christian at Castle’s Woods. Christian positioned the company under his personal command between the other two so that he could “hurry down” to assist the communities on Blue Stone or Walker’s Creeks, cover the Clinch settlements, or march wherever else Preston might need him to go.49

Despite the troops’ presence, a number of Moccasin and Copper Creek families abandoned their farms after hearing someone had sighted Indians—or tracks they perceived as left by Indians—near Sandy Creek. Obeying Preston’s order, Captain Robert Doack drafted some men from his company and marched to the heads of Sandy Creek and Clinch River. Upon hearing that Doack had mustered a force of no more than ten, the colonel diverted Crockett’s company to relieve the drafted men. On arriving, the ranger captain relayed Christian’s instructions that Doack “might as well disband or range a few days” with Crockett until events or orders dictated otherwise. Shortly thereafter, the two captains received an unconfirmed report of sixteen Indians on Walker’s Creek. Doack led his men to investigate and take appropriate action, but “not finding any Signs & hearing the News Contradicted,” he discharged his drafted men as ordered.50

After hearing that residents had fled the Rich Valley and Walker’s Creek area “in great Confusion,” Christian ordered Doack to send scouts to investigate. The captain noted that although they had left their farms, “The People are all in Garrisons from Fort Chiswell to the Head of Holston.” He observed that in the event of an attack, the community only had enough militiamen to adequately man two, but not all three, of the forts they had built. Doack recommended posting a “Sergeants Command” of seven or eight men in actual service—not taken from the rangers—at each fort to increase the “protection & encouragement” of the community. The additional full-time soldiers provided the area’s farmers extra security, which also encouraged them to save their crops and not abandon their homes. Furthermore, the next time the Indians attacked, the guards provided a force “Ready to follow the Enemy” immediately, whereas local militiamen would first make sure their families took shelter in the fort before they would be available.51 “Let the party be ever so small,” Doack wrote, offering to command one such detachment regardless of size. Since a fifteen-man detachment required only an ensign and sergeant to command it, Doack indicated his willingness to serve at the pay of a subordinate officer, even if not commensurate to his rank. In seeking any assignment during the crisis, he volunteered to go wherever Preston commanded and wished rather “to be Serviceable than to look for high pay” at that critical time.52

When Colonel Christian and his company arrived in Castle’s Woods on Sunday, July 10, he found Captain Russell well in control of the situation there. Despite the diminished threat of war with the Cherokees, the competent Russell considered the inhabitants along the Clinch more vulnerable to attack from the Shawnees than their neighbors on the Holston. Two weeks had elapsed since he sent Boone and Stoner in search of Floyd and the other surveyors. Although he had yet heard nothing, he remained confident they would find them safe and expected their return any day. The captain had other scouts “out continually on Duty” at the heads of the Louisa and Big Sandy Rivers, about Cumberland Gap, and down the Clinch, looking for any signs of either the surveyors or approaching enemy raiding parties. Patrols regularly went to “reconnoiter the very Warriours Paths most convenient” to the Clinch River settlement and with which the rangers under Christian’s command had not yet become familiar. With no little amount of pride, Russell described those he commanded as “Men that may be depended on” and expressed confidence that any enemy raiders “cannot come upon us, without being discovered, before they make a stroak.” Even if they evaded the patrols, Russell knew that his company would meet them with the “probability of Rewarding them well for their trouble.”53

Although Russell’s company originally voted to build two forts for the government, they had altered the plan to add a third. When Colonel Christian arrived, he noticed four forts “erecting on Clinch” to guard the frontier from invasion and shelter the local inhabitants. Russell had named the post at Castle’s Woods, which also served as his headquarters, Fort Preston. Twelve miles upriver, on Daniel Smith’s property, the men neared completion of Fort Christian.

Fort Byrd stood on the property of William Moore, four miles down the Clinch at the mouth of the creek that also bore the family’s name. At Stony Creek, another sixteen miles down, four families had joined to fortify the home of their neighbor, John Blackmore. Although not intended as a military post like the other three, Blackmore’s fort provided shelter for travelers and nearby residents. Because of its isolated location and dispersed number of inhabitants, Russell worried for their safety and the adequacy of their defenses.54

Despite the measures he had taken, Russell saw room for improvement and requested the county lieutenant’s assistance. He described his unit’s ammunition supply as “so bad” that he had little usable powder and only “fifty wt. [fifty-six pounds] of Lead.” He had dutifully requisitioned more, but a week had passed since Major Campbell assured him that he could expect delivery, with no sign of the powder. The captain also requested that Colonel Preston order some of his men into actual service, or full-time duty, to better defend that part of the county. “Tho’ the pay of the Country as soldiers cannot be thought Adequate to such risques,” Russell explained that in a small measure it could at least encourage the people to “stand their Ground.” Even if the anticipated war never started, the pay would at least offer the men some compensation for their labor in building three fortifications to defend the province’s border. They could have easily avoided the drudgery, as Russell reminded the colonel, by deserting the frontier until the danger subsided. The very presence of soldiers encouraged others to refrain from abandoning the Clinch settlements and thereby expose the Holston communities to attack.55

Captain Campbell’s company arrived in Castle’s Woods the next day, Monday, after marching thirty miles up Clinch River from Moccasin Gap. Noting the two ranger companies in his community, Russell no longer concealed his disappointment that Preston and the council of war had not selected him to command one of them. Although “satisfied the gentlemen Officers appointed to the present Detachment, are worthy men . . . as Zealous to serve their Country” as the officers of his own company, he felt slighted at not receiving the assignment. However, Russell conceded that “they might Destroy some of the Enimy in a Week or two.” Russell possessed military experience, leadership abilities, and an extensive knowledge of the frontier that few could match. 56 Furthermore, the memory of finding his murdered son’s mutilated body just ten months before still haunted him and kindled his desire for revenge. Although the events in Powell’s Valley had made this fight personal, Russell, ever the good soldier, placed the country’s interests above his own.

In all, Christian now had the one hundred men of the two ranging companies, plus Russell’s militia company, within his immediate command, with Crockett’s forty men not far away in case of trouble.57 Before the continued his primary mission, Christian first had to gather provisions for his rangers. He sent parties with packhorses to collect and carry one thousand five hundred pounds of flour and corn back to Fort Preston. Although in need of beef cattle, he hesitated in sending parties to Holston to drive forty head back until he knew Preston’s instructions for the next phase of the operation.

Christian concurred with Russell in believing that Boone and Stoner would find the surveyors alive and soon return, although unaware by which route. Christian therefore delayed marching to the heads, or sources of the tributary streams, of the Louisa River to meet them as Preston had originally instructed. Instead, he convened a two-day council of war with the officers present at Castle’s Woods to develop a course of action that would satisfy the governor’s instruction for the county lieutenant to take offensive action and seek Colonel Preston’s approval to execute it. Christian proposed that a force of 150 to 200 men, with five packhorses allowed for each fifty-man company to carry their “Baggage & Blankets & such like” equipage, could march the estimated 120 miles from Castle’s Woods to the Ohio opposite the mouth of the Scioto. There, he would leave “the tired & lame Men” incapable of going farther to erect a small blockhouse to support the best men, who would cross the river and cover their retreat in case of defeat. Once on the north bank, the main force of 150 men would move toward the enemy town. With a “good Pilot,” or guide, familiar with the trails of the area to “lead us thro’ the Woods either by Night or Day,” they could advance the last forty-five miles through terrain “where an Enemy would not be expected,” to reach the town undetected and conduct a surprise attack.

Christian counted the forces he had available. Russell indicated he could enlist thirty volunteers from the Clinch. The three lower companies on Holston could detach seventy-five. With the 140 rangers and militia already on duty in the area, Christian had the two hundred “choice” men he needed without having to call Captain Crocket’s company, which he could leave to protect the frontier. To preserve the element of surprise, the officers agreed to say nothing publicly concerning an attack on the Indian town but only disclosed that they proposed going “to the Ohio & returning up New [Kanawha] River.” Although some questioned if they could rely on having a sufficient number of troops willing to cross into Indian country not knowing the plan beforehand, they had confidence that “after going so near the Enemy’s Country,” enough would certainly do so. In the unlikely event that a sufficient number of volunteers did not step forward to effect the expedition, they agreed that executing the alternate plan of marching up the Kanawha “might be of considerable Service” in providing security for the settlements. If the enemy attacked a settlement on the south bank during his foray, Christian would ask Preston to send him “speedy notification” so that his force could move to intercept the enemy raiders on the banks of the Ohio as they returned.58

While he waited for Preston’s decision, Christian thought it “better to keep the Men moving slowly than have them remain in camp.” He therefore distributed the 115 militiamen in actual service to the various forts to strengthen the garrisons guarding the Fincastle County frontier. As Russell had recommended, he posted thirty men each at Blackmore’s fort and at the head of Sandy Creek, and ten at Fort Preston in Castle’s Woods. He sent Captain James Thompson with ten men to Fort Byrd on the Moore farm, and another ten men each to James Smith’s fortified home and Captain Daniel Smith’s, and fifteen to Cove and Walker’s Creek.59

While Christian and his subordinate commanders waited for Preston’s decision, Colonel Andrew Lewis received new instructions from Dunmore. The governor, making his way west from Williamsburg, had now fully digested the county lieutenants’ descriptions of the situation on the frontier and recognized that “so great a probability” of an Indian war required immediate action by the colony. He repeated his advice to wait no longer for the Indians to continue their attacks but to “raise all the Men . . . willing & Able to go” and immediately march to the mouth of the Kanawha. After building a fort, if Lewis had sufficient forces available, the governor instructed him to advance against the Shawnees and “if possible destroy their Towns & Magazines and distress them in every other way that is possible.” He told Lewis that a “large body of Men” had already marched from the Shenandoah valley under Major McDonald’s command and could join him there. By keeping communication open with Fort Fincastle at Wheeling and Fort Dunmore at Pittsburgh, the governor believed the militia would prevent any more war parties from crossing the Ohio to attack Virginia inhabitants.60

Somewhat taken aback by the governor’s apparent lack of understanding about the frontier counties’ situation, Lewis immediately wrote to Preston that his lordship had taken for granted their ability to “fit out an Expedition” and ordered one. Although their “backwardness”—meaning reluctance—might have surprised Dunmore, Lewis feared the consequences of mounting an offense while preoccupied with defense elsewhere. He resolved to do something, telling Preston he would rather accept great risk doing something than to allow an unsuccessful outcome by doing nothing. He therefore ordered the county lieutenant of Fincastle to embody a force of at least 250 men to take the field under his personal command.61

After he received Lewis’s instructions, Preston sent a circular letter to the field officers and captains commanding companies to raise the county’s “reasonable” quota of volunteers. Preston believed the men “should turn out cheerfully” to defend their “Lives and Properties,” which had “been so long exposed to the Savages,” who had enjoyed “too great success in taking [them] away” from the settlers. Moreover, if they neglected to act, they may never have “so Fair an Opportunity of reducing our old Inveterate Enemies to reason.” He assured them of Dunmore’s commitment to the project’s success and confidence that the House of Burgesses would vote the necessary expenditures that would “enable his Lordship to reward every Volunteer in a handsome manner over and above his Pay.” With that, Preston added the enticement of a time-honored bonus. “The plunder of the Country,” he continued, “will be valuable, & it is said the Shawanese have a great Stock of Horses.” Taking items with intrinsic military value as spoils of war from the enemy— whether strictly martial and purchased by the government, or sold on the market with the proceeds distributed to the soldiers, or converted to private use by individual recipients—represented an added inducement for enlisting. The practice also served as a means of forcing one’s enemy to bear the economic burden of supporting military operations in his country.

The invasion of Shawnee territory was intended as a reprisal for the series of attacks in the backcountry and not a war of conquest. A successful campaign offered two immediate benefits. First, it would be the only way of “Settling a lasting Peace with all the Indian Tribes” whom the Shawnees had urged to engage in war against Virginia. Second, if the Shawnees suffered the same manner of destruction as they had inflicted, with their towns plundered and burned, cornfields destroyed, and the people “destressed,” the punitive expedition could render them incapable of attacking Virginia again in the future and possibly oblige them to “abandon Their Country.” Preston therefore hoped the men would “Readily & cheerfully engage in the Expedition.” He told the men he and other county lieutenants expected “a great Number of Officers & Soldiers raised behind the Mountains” to join the expedition for the same motive of home defense. Preston assured the Fincastle County men that they would serve in their own units commanded by their own officers and not be reorganized into units other than those in which they enlisted. He then informed potential volunteers that fifty-four-year-old Colonel Andrew Lewis would command the expedition. Despite his advanced age, the country called on him again for his “Experience, Steadiness & Conduct on former Occasions.” Lewis was respected and admired throughout the frontier districts, and the knowledge that he was in command enhanced the effort to attract volunteers.

Preston concluded his letter with an appeal to their pride, as he called every man to give his utmost exertion because so much depended on the expedition’s success. With “the Eyes of this & the Neighboring Colonies” on them, he challenged Fincastle County to not leave it to its neighbors to contribute the men, provisions, and any of the other necessities they could spare. Their governor had called them. Their county stood ready to pay and support them. Other counties would join and assist them. They fought in a good cause and had “the greatest Reason to hope & expect” heaven would bless them with success and defend them and their families against “a parcel of Murdering Savages.” The opportunity for which they had waited and wished for so long had arrived. “Interest, Duty, Honor, Self-preservation, and every thing, which a man ought to hold Dear or Valuable in Life,” he said, “ought to Rouze us up at present; and Induce us to Join unanimously as one man to go [on] the Expedition.” Preston reminded them of the hardship that awaited them but assured them of the rewards victory would bring.62

Virginians in the frontier counties began to hear the strains of the song known as “The Recruiting Officer” with increased frequency in 1774. They heard it played and sung in taverns and ordinaries, at social gatherings, and by soldiers on the march. Although it was an old song that dated from the first decade of the eighteenth century, it remained a popular air, and a most appropriate one for the time and place.

The song originated in 1707 during Queen Anne’s War. Following passage of the Acts of Union, which united England and Scotland as the kingdom of Great Britain, Virginians, like other colonists, proudly identified themselves as British subjects. European conflicts increasingly included operations in the New World, and American Britons sacrificed blood and treasure for the empire. The Recruiting Officer, George Farquhar’s acclaimed musical comedy from the London stage, made its way across the Atlantic and remained in America as a legacy of Queen Anne’s War. A professional theatrical company toured the colonies, and as in Britain, the play became an immediate hit and perennial favorite. The first edition of William Parks’s Virginia Gazette advertised that “The Gentlemen and Ladies of this Country” staged The Recruiting Officer in Williamsburg in September 1736.63

For the title song, Farquhar adapted the melody of Thomas D’Urfey’s familiar ballad “Over the Hills and Far Away,” added the accompaniment of a single drum beating the army’s “Recruiting Call,” and penned new lyrics. Also known as “The Merry Volunteers,” the song became popular in its own right, especially among veterans and members of the militia. After Governor Dunmore instructed the frontier county lieutenants to raise troops to fight the Indians, recruiting officers, some accompanied by drummers beating the familiar call, appeared at muster fields, courthouse squares, and wherever military-age men gathered. During summer 1774, Virginians heard “The Recruiting Officer” almost everywhere:

Hark! Now the drums beat up again,

For all true Soldiers, Gentlemen,

Then let us ’list, and march, I say

Over the hills and far away.64

WHEN WHITE EYES returned to Pittsburgh on July 23, McKee immediately convened a council for the colonial officials to learn the latest news from the Indian side of the Ohio. The message the Delaware chief delivered to “our Brethren of Pennsylvania . . . and Virginia” laid to rest all doubt as to the Shawnees’ intentions. He told them that Sir William Johnson, “with our Uncles the Five Nations, the Wyandots, and all the Several Tribes of Cherokees and Southern Indians,” had spoken. They all told the Delaware to “hold Fast the Chain of Friendship” and be strong in refraining from taking the warpath. To that end, he said, the various bands of Western Delawares, including the Munsees, “will sit still at our Towns . . . upon the Muskingum” and maintain the peace and friendship “between You and us.”

Since the Pennsylvanians desired to keep the road between them “clear and open” so the traders could pass safely, the Indians asked that the white people not allow their “Foolish young People to Lie on the Road to watch and frighten our People by pointing their Guns at them when they Come to trade with you.” Such behavior scared “our People” and “Alarmed all our Towns, as if the White People would kill all the Indians” regardless of whether they were friends or enemies. White Eyes turned to the Virginians and told them that the Delawares “now see you and the Shawanese in Grips with each other, ready to strike.” At a loss, they said they could do or say nothing that would reconcile the two sides. He relayed the message that the Delawares only asked that after the Virginians defeated the Shawnees, they neither turn their attention against the other tribes nor start settlements on the north bank of the Ohio. Instead, they urged the Virginians to return to the Kanawha and south side of the Ohio after they had “Concluded this Dispute” with the Shawnees and renew the old friendship with all other nations.

Croghan replied that the Shawnees had exhibited evident proof they did not mean to be friends with either the Delawares or the Virginians. He therefore asked White Eyes to approach the Delawares to ask if they would not think it prudent that some of their warriors accompany the Virginia troops when they go to “Chastise the Shawanese.” Such a service would not only shield them from their common enemy, but they could help the Virginia soldiers make a “proper Distinction between our [Indian] Friends and our Enemies.” White Eyes replied that he would take that message to the Delaware chiefs at Kuskusky and return with their answer.65

Alexander McKee provided Aeneas Mackay a copy the speeches White Eyes had brought back from Newcomer’s Town in order to transmit them to Governor Penn. Before forwarding the packet to St. Clair, he met with Devereux Smith, Joseph Spear, and Richard Butler to discuss a plan they wished to recommend to the provincial government in Philadelphia. They felt it absolutely necessary for Pennsylvania to reward the fidelity of the Delawares, especially “such of them as will undertake to Reconnoiter and Guard the frontiers of this Province . . . from the hostile Designs of the Shawanese.” Since performing military service on behalf of Pennsylvania would prevent them from following their own occupations of trapping and hunting, the committee thought it “no more than right to supply all their necessary wants while they continue to Deserve it so well at our hands.” In the absence of a Pennsylvania armed force, instead of subsidizing a colonial militia, these men of means in Pittsburgh favored a defense policy in which their provincial government hired Delaware warriors as mercenaries to defend them.66

St. Clair, in turn, forwarded the speeches along with the latest intelligence concerning the crisis on the frontier to Governor Penn. He said that any prospect of an accommodation between the Shawnees and Virginians was certainly over, and had been for some time. He added his unwavering insistence that it did not appear that the Shawnees had any hostile intentions against Pennsylvania. He then endorsed the recommendation for “engaging the services of the Delawares to protect our Frontier” and believed that it would undoubtedly be a good policy if it did not cost too much. Although the magistrate anticipated the Indians would be “very craving” of any rewards, he did not think the provincial assembly should overlook the proposal. He recognized a single consistent truth: “These Indian disturbances will occasion a very heavy Expence to this Province.” Therefore, regardless of whether or not they engaged the services of their warriors, St. Clair urged that the province secure the Delawares’ friendship “on the easiest terms possible.” He neither trusted Croghan with a free authorization to spend the province’s money nor wanted to insult the Indians with too parsimonious a gesture. If the governor thought it was proper to reward the Delawares with presents, St. Clair recommended that he specify what items he wanted Croghan to obtain and give them.

Captain White Eyes and John Montour assembled and began preparing a party of warriors, including Delaware and Six Nations Indians, who planned to accompany Virginia militia troops if they crossed the Ohio River to attack the lower Shawnee towns. Connolly once again approached St. Clair and requested that he order some of the Westmoreland rangers to cooperate and join the expedition as well. The Pennsylvania magistrate again refused and sent specific orders that they were not to cross the rivers that defined their area of operation, much less join the Virginians, “who have taken such Pains to involve the Country in War.” Instead, St. Clair still insisted that he wanted the Shawnees to know “this Government [Pennsylvania] is at Peace with them” and would so remain so long as the Indians did not invade the east side of the Monongahela and cause “mischief.” Such action, he warned, would result in an immediate declaration of war and swift reprisal by the Pennsylvanians. 67

IN MID-JULY, Governor Dunmore established his temporary headquarters at Greenway Court, near Winchester, the estate of the county lieutenant of Frederick County, as well as his fellow peer of the realm, Thomas Fairfax, Sixth Lord Fairfax and Baron of Cameron. Toward the end of the month, Dunmore ordered some weapons and ammunition from the provincial magazine at Williamsburg brought west to supply some of the units he called out for service. On Wednesday, July 27, a convoy of wagons loaded with “300 stand of arms, with the proper accoutrements,” including muskets, bayonets, and cartouche boxes, as well as eight casks of sifted gunpowder, left the capital for Winchester.68 Dunmore, the former British army captain, now commanded a field army preparing for war.