CHAPTER 11

A Hard Fought Battle

Point Pleasant

October–November 1774

IN KEEPING open the offer he made at the end of the council held at Pittsburgh, Lord Dunmore waited for Cornstalk and a delegation of Shawnee chiefs to meet for one last attempt to forestall war. As the calendar turned from September to October, winter would soon bring the campaign season to an end. Time was of the essence for a resolution, either diplomatic or military. The governor had yet to hear from Colonel Andrew Lewis and therefore did not know when the two wings of his army would join to execute the invasion of Shawnee country as planned, if the final attempt for a negotiated settlement failed. Recent Indian raids on the settlements seemed to indicate the conflict would continue until the Virginians took decisive action. With time running out, Dunmore faced a situation that offered little cause for optimism.

ON OR about October 7, Cornstalk called a council of war with the Shawnee military chiefs, leading warriors, and the “captains” of the allied warrior bands. He had received accurate and timely intelligence from a variety of sources, which he could use in developing a plan of action. The scouts who had watched Colonel Andrew Lewis’s command ever since it assembled at Camp Union and hovered on the flanks of each marching division now had the camp at Point Pleasant under observation. War parties returning from raids against the settlements along the Monongahela and elsewhere in Augusta County, as well as Pennsylvania traders from Kittanning, brought information on the right wing’s movements and the camp established at the mouth of the Hockhocking.

All that he heard made Cornstalk aware of the situation he now faced. He knew that Dunmore’s army would enjoy a three-to-one numerical advantage over his when the two divisions joined forces. As good as their warriors were in individual combat, the armies of the various Indian nations suffered from a general strategic and logistical weakness in the ability and capacity to conduct lengthy campaigns or endure long battles of attrition. The petite guerre, or guerrilla war, offered the American Indian nations the best chance of martial success. They had come to realize that they could prevail in conflicts of short duration if they achieved quick yet stunning victories. Indian forces therefore aggressively took the offensive and fought brutal battles of annihilation when presented with a reasonable chance of winning. Seizing or holding ground did not figure in tactical planning or constitute a measure of success. Indian warriors fought primarily to inflict heavy casualties and thereby destroy or demoralize their opponents.1

An astute commander, Cornstalk knew it would take the Virginians several days before they could unite their separated forces. He proposed a bold plan, risky yet tactically sound, to attack with his concentrated strength while the Virginians were still divided. Doing so allowed his forces to fight each of the enemy’s wings separately on nearly equal terms to defeat them in detail. It combined the advantages inherent in offensive action as well as what military planners call interior lines, with the element of surprise to multiply the combat power of his army beyond the number of its warriors. If the Shawnees and their allies destroyed one wing of the Virginia army at the mouth of the Kanawha, they could then move to attack the other as it advanced along the Hockhocking before it threatened the principal Shawnee and Mingo towns on the Upper Scioto. Given the native disdain for their enemy’s fighting abilities and methods of warfare, Cornstalk believed the warriors could strike devastating blows before the Virginians advanced too far into his people’s territory. Furthermore, he believed that inflicting heavy casualties would demoralize the militiamen and convince Lord Dunmore to halt the campaign before it cost more blood and treasure than the colony was willing to pay. Offering the best—if not only—hope, the plan would allow the Indians to forestall strategic defeat even without achieving a decisive tactical victory.

That night, the sound of drumming was heard about the several Shawnee and Mingo towns and villages as the captains of war parties gathered the men who had pledged to follow them. With each warrior holding a tomahawk, spear, or war club, they chanted their war songs and moved forward across a clearing at the town’s center by the council house performing their war dance. After taking his place in line, each warrior advanced and struck toward the war post. When the last man finished, the warriors applied their war paint. They reassembled the next morning. Stripped for battle, wearing only breechcloths, leggings, and moccasins, and carrying a few provisions in packs on their backs, the several groups marched away as their families watched them depart.2

Although Cornstalk’s army consisted mostly of his own people and Mingoes, braves from the Delaware, Ottawa, Miami, Wyandot, and “several Other Nations” increased the size of the force. Whether they were motivated by a desire to gain reputation and status or simply to fight a hated enemy, the opportunity to take some Big Knife scalps led them to ignore their chiefs’ orders or defy the pronouncements of their Six Nations overlords to aid the Shawnees. While Cornstalk had some warriors remain behind to guard their families and towns, and raiding parties operated against the settlements, estimates vary of the total number of fighting men who formed “the whole United Force of the Enemy Ohio Indians” and took the warpath. Although one officer who arrived at Point Pleasant after the battle opined that Cornstalk led “not more than five hundred at most,” others put their strength as high as about one thousand. Most Virginia participants, particularly those who took part in the engagement, estimated the strength of Cornstalk’s mobile force at between seven hundred and eight hundred fighters. Given the contemporary tribal populations with the traditional proportion of warriors as reported by the British Indian Department and colonial Indian agents, the most common estimate, seven hundred to eight hundred, appears to be the most accurate.3

White Eyes arrived at Chillicothe amid the preparations to deliver Dunmore’s invitation for Cornstalk and other leaders to meet him on the banks of the Ohio for a final attempt at negotiation. John Montour, the widely respected cultural mediator, or go-between, and a trader named William McCulloch (or McCullough) accompanied the Delaware chief. If anyone had a reasonable chance of bringing Cornstalk and the others to a council with the Big Knife, the Delaware White Eyes and the French-Iroquoian-Algonquian métis Montour did. Traders like McCulloch, who often rankled the ire of backcountry settlers for supplying weapons to the Indians, even in time of war, could have also helped White Eyes in his endeavor. Although the trader may have been a Pennsylvania partisan in the border dispute with Virginia, his friendly business relationship with the Shawnee could have maintained rapport in a contentious dialogue. Cornstalk, however, expressed no desire to negotiate further. He essentially informed White Eyes that “700 Warriors” had gone southward to “Speak with the Army there”—meaning Lewis’s left wing—instead of to Fort Gower to talk with Dunmore. The Indian commander continued by saying that the warriors heading toward Lewis’s force would “begin with them in the morning and their business would be Over by Breakfast time.” After that, the Shawnees and their allies would return north and “speak with his Lordship.” 4

WHITE EYES, Montour, and McCulloch arrived at the mouth of the Hockhocking the day after Dunmore established his headquarters at Fort Gower. The governor recorded that he received “disagreeable information” conveyed by “our friends the Delaware.” The mediators relayed the Shawnees’ defiant reply that they would “listen to no terms” at that time. Instead of resuming negotiations, they had “resolved to prosecute their designs against the people of Virginia.”5 Having received no recent correspondence from Colonel Andrew Lewis to gauge how long it would take his division to reach the rendezvous, the governor once more amended the campaign plan to the new requirements. “Unwilling to increase the expense of the Country by further delay,” he decided to press forward into Indian country from both Point Pleasant and Fort Gower, with the two wings converging on the Shawnee towns to join forces “about twenty miles on this side of Chillicossee at a large ridge.” The governor drafted the new orders and sent Kenton, Girty, and Parchment back to Point Pleasant, this time accompanied by McCulloch, to deliver them to Colonel Lewis.6

White Eyes had offered to raise a force of Delaware warriors to accompany the army against the Shawnees. Keenly aware that backcountry Virginians generally harbored a “natural dislike” of all Indians, even those of the friendly nations, the governor declined the generous offer. As a practical matter, he wanted to avoid any threats to good order and discipline that could result from even a minor misunderstanding between people of different cultures. Dunmore graciously thanked the chief and accepted the services of only a few Delaware scouts. From the intelligence he had received concerning the numbers of warriors the Shawnees and their Indian allies had gathered to fight against him, Dunmore believed that his army had sufficient strength “to defeat them and destroy their Towns” if the Shawnees still refused his last “offers of Peace” when they saw the Virginians approach.7

WHEN THE left wing marched from the Elk River on October 1, Colonel Andrew Lewis ordered the troops to form two columns, or “grand divisions,” with the Augusta County line constituting the left division and the Botetourt County line constituting most of the right column. Each line posted one company in both the advanced and rear-guard detachments—on the left and right respectively—with four men from each also detached as flankers. The Botetourt County company of Captain John Lewis, Andrew’s oldest son, detached a sergeant and twelve soldiers to move with the guides ahead of the advance guard, while a company from the Augusta line detached a similar party to trail behind the rear guard. The main body, about four hundred men, formed with front and rear divisions, or four subdivisions, and with an ensign’s command of sixteen men acting as flankers to each side. The cattle herd and packhorse train with their guards “fell in betwixt the Front & Rear sub-divisions” of the main body. The march order reflected the doctrine found in Bland’s Treatise, albeit modified for use in the North American wilderness, much as Colonel Henry Bouquet had also done with the “marching square” formation he employed on his expedition against the Shawnees during Pontiac’s War. The convoy of eighteen supply canoes, plus those of the sutlers who accompanied the army, kept abreast of the marching columns during the day and banked near the latter’s camp each night.

With the soldiers deployed in such a formation, Colonel Fleming explained to future readers of his journal how the column had an established and well-practiced battle drill to respond to a threat from any direction. In a head-on meeting engagement, or if the enemy attacked the column in front, the advanced guard would “Free themselves & Stand the Charge” while the right and left columns moved to outflank the enemy and then “Close in &c.” to finish them. Regardless of “whatever Quarter, Column or Van or Rear Guard” the enemy attacked, the colonel continued, those directly under attack would “Stand the Charge” while the unengaged “Distant Columns” attacked the enemy’s own flanks. The left wing, therefore, moved while deployed in this formation, except where the terrain proved too restrictive and dictated otherwise. After it left the mouth of the Elk, the wing marched to a point on the Kanawha opposite the mouth of Coal Creek and halted. Repeated with little change every day of the march, the order for encamping prescribed the priority tasks that the force had to accomplish before dark. The responsible line held guard mount and posted main and picket guards for security. Cattle drovers and packhorse drivers turned their animals out to graze. Boatmen banked and secured their canoes. The butchers slaughtered the necessary number of beeves and issued the various messes their daily fresh meat ration. Officers inspected their companies and arms. The men cooked their rations for the evening meal and next morning’s breakfast. As the sun began to set, the secured camp settled in for the night.8

On October 2, the army marched through “rich Bottoms & muddy Swamp Creeks,” encountering the latter obstacles about every mile or half mile so that the packhorses, according to Fleming, became “much Jaded.” About two miles from the previous night’s encampment, some of the troops marched through the ruins of an “Indian fort” positioned along a branch of the warriors’ path that also functioned as a trader’s trail. Probably the remnant of an earlier conflict, the oval-shaped feature measured about one hundred feet in length with a “cellar full of water 8 feet broad,” and “banks” that stood three feet high above the surface of the water. Meanwhile, out on the Kanawha, one of the sutler’s canoes “overset,” with the loss of “two guns . . . & some baggage.” Another watercraft, fashioned from two canoes fastened together, also “overset.” Although two or three of them got “much wett,” the twenty-seven bags of flour floated long enough for boatmen to recover the entire cargo. So that the dampened flour would not spoil in transit, the commissary issued every soldier a two-day ration at the next halt. While morale generally remained high, Fleming noted that the army had experienced a few breaches in discipline since it marched from Camp Union. Since leaving the camp at the Elk, in addition to the theft of some provisions, infractions included the desertion of a sergeant and three men who left the army without being granted leave.

The column continued to move through rich bottomland until it reached the steep and “very Muddy” banks of Pocatalico Creek. The men trudged through the stream at a ford where the water measured some forty feet wide and three to three-and-a-half-feet deep before the column continued another mile past the river’s mouth and halted to camp for the night. As the accompanying supply convoy paddled down the Kanawha parallel to the marching column, another sutler’s canoe capsized, and one more of the supply laden “double canoes Split” and sank. The boatmen’s efforts again saved most of its cargo of flour.

Major Ingles urged the cattle drovers to keep the herd together as much as possible as the division continued to negotiate several defiles with high steep banks and along hillsides with steep slopes that came so close to the water of the Kanawha at times that it forced the two columns to compress and march together on a single path. On October 5, the lead scouts found the camp that the advanced “spies” had used before they sent Private Fowler back to the Elk in the canoe and continued overland to accomplish their mission on foot. A squad of men who stayed behind at the previous night’s camp to gather straggling cattle caught up with the main body at the end of the day’s march. They reported having observed an Indian warrior, “suppos’d a spy,” investigate the now-abandoned bivouac site with great interest.9

Finally, on Thursday, October 6, after Colonel Andrew Lewis’s Southern Division, or left wing, of the army had marched through “many defiles, cross’d many Runs with Steep high & difficult banks” for about eight miles, the column entered a bottom that stretched along the Kanawha for another three and three-quarters miles to its confluence with the Ohio. Colonel Fleming described the point of land as rising high and affording “a most agreeable prospect” for establishing an encampment. He looked across the two rivers at the confluence to the opposite banks. He estimated the width of the Ohio as seven hundred yards, while the “deep still water of the Kanawha” extended four hundred yards across at the mouth. The colonel determined that the middle ground of the point stood ten feet above the water, and he observed that the elevation gave it “an extensive View up both rivers & down the Ohio.” After posting local security for what became the Camp on Point Pleasant, the officer of the guard assigned the now-routine force of an ensign’s guard of eighteen men on the canoes and ammunition. The commissary, Major Ingles, reported to Colonel Andrew Lewis on the exact number and condition of the beef cattle and ordered the canoe men to do their best to cover the flour supply in order to protect it from moisture, while the quartermaster, Major Posey, ordered his assistants to take special care to secure and preserve the ammunition.

The advanced scouts—Fowler’s companions—reported to Colonel Lewis that they had seen no war parties or signs of the enemy present since they first reached and subsequently ranged about Point Pleasant. The men had observed several Indian hunting parties tracking buffalo but were careful to avoid detection as the hunters pursued their quarry. Of the most consequence, the scouts reported finding no indication that the Northern Division had reached Point Pleasant before them, but they discovered the “Advertisement” Kenton, Girty, and Parchment had posted. The messengers’ notice advised members of the Southern Division they would find a letter from Dunmore “lodged in a hollow tree.” That document contained the governor’s order, which had been overtaken by more recent events, for Lewis to march his men upriver to join forces with the other division at the mouth of the Hockhocking.10

COLONEL CHRISTIAN and the Southern Division’s rear party left Camp Union on September 26 and reached the mouth of the Elk River in eight days. The men unloaded the supplies from the packhorses and placed them in the magazine. Christian put Captain Slaughter in command of the post, which included the magazine and its staff of assistant quartermasters, and a garrison comprised of “all the Lowlanders,” or the men in the companies from Dunmore and Culpepper Counties. He instructed Slaughter to load twenty-four thousand pounds of flour aboard the canoes when they returned from downstream in order to transport it forward to the main body. Christian sent Privates James Knox and James Smith of Robertson’s company, along with two other men, to learn the latest news on the situation at Point Pleasant. The men also carried an express to inform Colonel Andrew Lewis that the rear body would march for Point Pleasant with 350 head of cattle on October 6. Christian added a summary of his orders to Slaughter, which included his explanation that when the canoes returned, the Elk River garrison would keep a provision of fifty beeves and some flour.11 Captain Bledsoe prepared to lead the last division of the rear body from Camp Union on October 16, and hoped to reach Point Pleasant with two hundred loaded packhorses and eighty additional head of cattle in twelve days.12

BEFORE THE REVEILLE sounded at Point Pleasant on Friday, October 7, the order went out to all the subordinate commanders to take a complete roll of their units and follow the camp routine established at Camp Union and the Elk River until the division marched again. In its V-shaped camp layout, or castrametation, the Southern Division headquarters occupied the vertex at the point, with the Botetourt County line—including the attached companies—erecting its shelters for one-half mile along the Ohio, while the Augusta line’s tents stretched a similar distance along the Kanawha. Fleming described the area between the two lines of tents as “full of large trees & very brushy.” The routine of daily camp duties kept the men busy on numerous tasks. In addition to local patrols, picket duty, and daily guard mount, fatigue details occupied much of the soldiers’ time. Preservation of the health and welfare of the troops dictated that building a “Necessary House,” or latrine, ranked among the first tasks accomplished, lest the camp become “fouled & sickly.” Similarly, general orders reminded company officers to encourage their troops to preserve their own “health & Satisfaction,” as well as avoid disciplinary action, and to use the latrines rather than “ease themselves” at various locations around the camp.

Getting the canoes unloaded as soon as possible also ranked high among the priority of tasks. Over the next few days, Lieutenants James and Hugh Allen of Captain George Mathews’s Augusta County company mustered as many artificers as they deemed necessary to construct a magazine, or “Shelter for the Stores.” Every day, Major Ingles had the horse and cattle drivers gather the animals that had wandered away from camp during the night, while Colonel Fleming sent an ensign in command of eighteen privates, six scouts, and some cattle drovers to return to the encampment of Wednesday night to search for and retrieve any beeves lost along the way, and drive them back to Point Pleasant.13 The next day, October 8, Ingles instructed the “Bullock drivers” to erect a pen large enough to accommodate the herd. The drivers let the animals range about the point and graze all day long but had to gather and confine them in the pen every night before the beating of retreat.14 After he learned that Colonel Christian’s two-hundred-man rear party had arrived at the Elk “with Bullocks and Gun Powder,” Sergeant Obadiah Trent, the division’s master boatman detailed from Captain Henry Pauling’s Botetourt County company, led the flotilla of canoes back upriver to the magazine in order to transport the flour and other stores back to Point Pleasant.15

After he read Dunmore’s message that directed him to march to join forces at the Hockhocking, Colonel Andrew Lewis conferred with his two principal subordinates, his brother, Charles Lewis, and William Fleming. The three colonels shared the opinion that the governor’s order was impractical to execute and offered little advantage to accomplishing the mission of the expedition. As the division commander turned his attention to drafting a reply to Dunmore, Colonel Fleming expressed the same concerns in a letter to Colonel Stephen, hoping that his long-time friend and comrade would share them with the governor as well. The strength returns showed that the division had “800 effective Rank & File”—not including officers, sergeants, musicians, and staff—at Point Pleasant, plus an additional “200 & odd men” following—under Christian’s command—within a distance of sixty miles. Colonel Andrew Lewis informed the governor that they had already endured a “very fatiguing march” when the main body reached the mouth of the Kanawha late on October 6, so that the left wing could not possibly leave Point Pleasant before Christian’s column—and the rest of the flour, packhorses, and cattle—joined him, and all the men and animals recovered their strength.

Lewis and Fleming also addressed the tactical implications of the new plan Dunmore had proposed. Having reached Point Pleasant, the left wing stood as close—or perhaps closer—to the Shawnee towns as the right wing did at the mouth of the Hockhocking. Affecting a juncture at that time offered no operational advantage, but only further delayed the advance. Confident of victory, Colonel Lewis explained that his officers and men saw the enemy as “within their grasp.” Furthermore, the officers considered the mouth of the Kanawha as the “pass into the frontiers” of the Virginia colony, particularly the backcountry settlements of Augusta, Botetourt, and Fincastle Counties. Marching north at that time, they argued, neglected or abandoned an important barrier and left the communities of their friends and families exposed and more vulnerable to invasion.16

Colonel Fleming explained to Stephen that the reasons that supported Dunmore’s proposed plan had to be “Overbalanced” by showing their arguments held more weight in order to convince the governor to countermand his order to march to Fort Gower. Fleming then stated that if they complied with the governor’s order as given, the resulting march away from the perceived critical point would only serve to “blunt the keen edge” of the Big Knife army pointed toward the enemy at the very time they needed to keep it honed sharp to deal with the Shawnees. Furthermore, he feared that it would only “raise a Spirit of Discontent not easily Quelled amongst the best regulated Troops,” much less militiamen unused to the “Yoak” of strict military discipline who had primarily volunteered to defend their homes. When the division’s field officers completed the response for their commander’s signature, Privates William Sharp and William Mann, two drafted men serving in Captain Andrew Lockridge’s company of Augusta County militia, carried it to Fort Gower for delivery to the governor.17

Lord Dunmore’s four messengers—Kenton, Girty, Parchment, and now McCulloch— arrived at Point Pleasant from Fort Gower with personal letters for Andrew Lewis and Fleming from Colonel Stephen, but more importantly, they had the governor’s latest orders. He directed the left wing commander to disregard the previous instruction and march to meet the right wing at the place “appointed near the Indian Settlements” instead. Dunmore and Lewis apparently reached the same conclusion, but their respective messages crossed in transiting the seventy-mile stretch of the Ohio River between the mouths of the Hockhocking and Kanawha. Sharp and Mann had left Point Pleasant carrying Lewis’s recommendation on Saturday, while Kenton, Girty, Parchment, and McCulloch arrived with the governor’s new order on Sunday.18

With “Guards Properly Posted at a Distance from the camp as usual,” and as the masters and artificers neared completion of the storehouse, the soldiers went about their duties on Sunday. Men of the several units attended divine services at noon to hear “a Good Sermon” preached by the Reverend Mr. Terrey. Some of the men discussed the “disagreeable news from Boston” that Stephen had conveyed in his letter to Lewis. Although the account that British regulars had fired on Massachusetts Bay militia proved to be only a rumor, it caused considerable angst among the soldiers who had been following the constitutional debate with interest. At the evening officers’ call, Colonel Lewis reminded the adjutants to send their units’ scouts for the next day to his headquarters early in the morning to receive their instructions for Monday’s patrols.19

McCulloch, the Indian trader who had accompanied the messengers, sought out his former acquaintance, Captain John Stuart, who was serving as officer of the guard. McCulloch found Stuart at his tent, and they talked while the trader waited on his companions to start the return trip. In the conversation, McCulloch mentioned he had recently returned from the Shawnee towns. Intrigued, Stuart asked the trader if he thought the Shawnees were “presumptuous enough to offer to fight” considering that the Virginians outnumbered them. McCulloch answered, “Ah! They will give you grinders, and that before long.” McCulloch kept repeating his answer to Stuart until his companions summoned him back to their canoe.20 In contrast, Major Ingles later reflected that the soldiers felt that they occupied the “Safe Position of a fine Encampment.” Given their presumed numerical superiority, the Virginians felt their army was “a terror” to all the Ohio area tribes. Perhaps “Lulled in safety” by overconfidence, after the drums beat retreat, Ingles “went to Repose . . . little Expecting to be attacked.”21

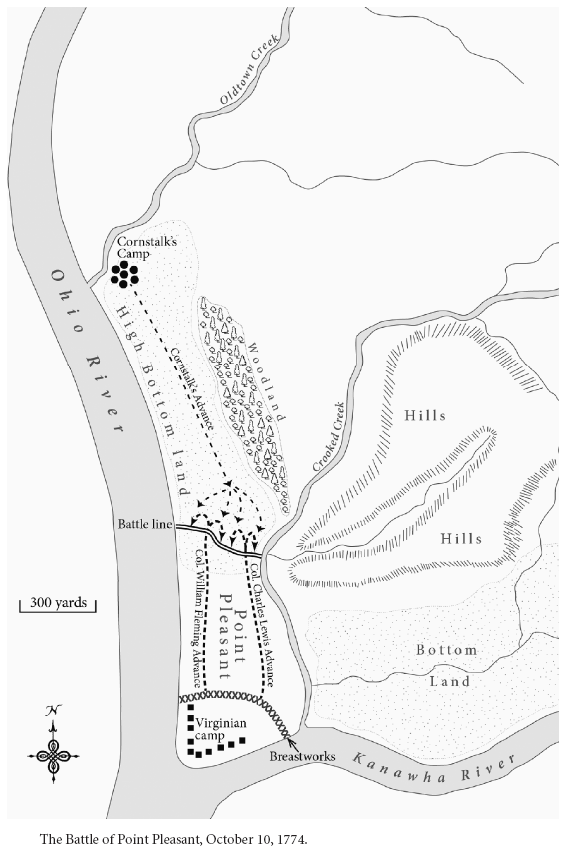

Despite the Virginians’ precautions and sense of security, Cornstalk’s forces were indeed close at hand. After arriving on the Ohio approximately six to eight miles upstream that day, the warriors built about eighty rafts and crossed the river. Once across, they advanced to the site of an abandoned Indian village and trading post known to many whites as the Old Shawnee Town, located at the mouth of Old Town Creek and about two miles from the Virginians’ camp. There Cornstalk’s army halted for the night and made its final preparation.22 Scouts had kept the enemy camp under observation, so that when Cornstalk and the other leaders met, they had the latest intelligence on their enemy’s defenses as they developed the plan of attack.23

In accordance with their method of fighting, warriors only sought a battle when they enjoyed a clear advantage and sure prospect of victory with the loss of few men. Therefore, they always looked to surprise and strike an enemy hard during a moment or condition of weakness. Once they lost a crucial advantage and could not easily overcome their opponent, they would—more often than not—disengage to minimize their losses rather than fight to a decision in the face of mounting casualties. If the tide of battle turned against them, warriors generally saw little reason to continue fighting. They did not consider breaking contact and quitting the field under such conditions as a sign of cowardice but a practical means of preserving their strength until they had the opportunity to defeat their enemy without losing many men. If surrounded, however, they would fight to the death rather than surrender, regardless of the odds.24

After a short night’s rest, the Indian warriors were up for the fight. Their leaders told them they would advance in a large body toward the Virginia camp, staying on high ground as much as possible, initially marching in single file and expanding as the terrain visibility dictated.

Just short of the Virginians’ camp, they would silently eliminate the pickets and form into a line. If still undetected, they would attack at first light, advance quickly in a rush to catch the enemy troops by surprise, either still asleep in their tents or awake but unprepared to form an effective line of defense against the assault. If all went well, the fury of the warriors’ assault would create such terror and confusion that the Big Knife soldiers would have to choose between two equally undesirable options, but both of which the Indians planned to exploit. Warriors would pursue and hound those remnants of the broken army that scattered and fled in the direction from which they had marched from the Elk River. Virginians who survived the onslaught and retreated to the Kanawha would either have to fight to the death on the bank or enter the water in a vain attempt to swim across the deep and wide river to safety. The fleeing soldiers would then find, to their dismay, the far banks lined with Indian warriors waiting to take them under fire and complete their destruction. Once he had ended the threat from the south, Cornstalk planned to return toward the Scioto in order to intercept Dunmore’s Northern Division, or right wing, as it advanced along the Hockhocking toward Chillicothe and the Upper Shawnee Towns.25

Stripped nearly naked and all encumbering clothing and equipment discarded, the warriors began “boldly marching to attack.” On encountering their enemy, the Indians at Point Pleasant most likely employed the tactics James Smith described in his captivity narrative. After his capture and adoption, the band of Canawauaghs (or Kahnawakes) accepted him as a warrior and trained him in their well-developed and oft-practiced tactics and techniques during the French and Indian War. He therefore experienced combat from an Indian perspective. He wrote that warriors advanced “under good command” and were “punctual” in obeying the shouted orders of their leaders. War parties executed a variety of maneuvers in which they changed from files into lines and stood, advanced, or retreated as quickly as necessary to fit the tactical situation. In the absence of spoken orders, each man guided his movement and motions by observing those of the companion to his right hand, and the man to his left guided on his. In doing so, according to the situation, they could “march abreast in concert” or in “scattered order.” When they sighted an enemy force, the leaders gave general orders with a “shout or yell.” In most engagements, they would advance in a semicircular formation to surround an enemy or assail an exposed flank to pin him against a natural obstacle such as a river. When the battle was joined, bands often employed tactics in which part advanced or retreated as the other part kept firing. If their enemy surprised them, the warriors would “take trees” for cover and face outward to prevent being surrounded. Individually, each warrior fought “as though he was to gain the battle himself” and sought every opportunity to gain every advantage over his opponent.26

At their camp on the opposite end of the point, some Virginians had just started to rise. Because Colonel Andrew Lewis had directed the commissary to have the butchers slaughter the poor quality beeves first, some company commanders decided to supplement their men’s meat ration with game. Early on Monday morning before the reveille beat, two men from each of the two Fincastle County units attached to the Botetourt line turned out to go hunting. Sergeants Valentine Sevier and James Robertson of Shelby’s company, and Privates Joseph Hughey and James Mooney from Russell’s took two separate paths in the direction of Old Town Creek. They had gone nearly two miles from camp when Sevier and Robertson “discovered a party of Indians” assembled near the abandoned town and immediately ran back to camp. The other two did not fare as well. A party of Indians saw them first and opened fire. Hughey fell dead, and Mooney, pursued most of the way, ran back to camp to give his comrades the alarm.27 Tradition holds that Tavenor Ross, a Virginian who had been captured and adopted by the Shawnees as a child during the French and Indian War, fired the shot that killed Hughey.28

Although concerned that the chance for surprise may have been compromised, Cornstalk gave the order and warriors began “boldly marching to attack.” The war parties initially moved in files along the trails that led through the woods. Despite heavy-growth timber, fallen tree trunks, and dense thickets that covered areas of the bottomland along the Ohio River’s south bank, the braves made their way forward as the predawn darkness gave way to increasing levels of light. With better visibility, the intervals between warriors expanded until the several files gave way to a large column that could take advantage of the terrain for ease of movement as well as have room to maneuver once it made contact with the enemy.29

The reveille had already sounded by the time Mooney reached camp. Giving the password as he raced by a picket, Mooney ran directly to Captain Stuart’s tent to inform the officer of the guard. The winded Mooney reported that he “saw above five Acres of land covered with Indians as one could stand one beside another.” Men who had heard the shots gathered outside of Stuart’s tent, curious to learn the cause, and listened intently. A few minutes later, as men continued to gather, Sevier and Robertson arrived to confirm the intelligence that the enemy was close at hand. Colonel Lewis immediately ordered the drummers to beat the to arms for men to retrieve their weapons, and then the alarm to warn everyone in camp of “sudden danger, so that all may be in readiness for immediate duty.” Everyone knew the procedure as drummers throughout the camp took up the beat and the field officers met with Lewis.30

After he considered the descriptions provided by the hunters and the lack of intelligence provided by recent patrols, Colonel Lewis assessed the situation. Although the enemy was present in a “considerable body . . . who made a formidable appearance,” he felt that what his division faced was a scouting party, albeit a large one. For a situation in which a commander’s unit encountered a “skulking party” of enemy irregulars, Bland’s Treatise of Military Discipline recommended that a commander order a “proper detachment” to go out to attack them. However, the treatise advised the commander to exercise extreme caution in execution and resist pursuing a retreating enemy too far for fear of an ambuscade or discovering the size of the enemy force “greater than what they apprehended” and “too advantageously posted to be easily dislodged.”31 Lewis adopted a course of action in keeping with that doctrine. He determined that an immediate reconnaissance in force to destroy, capture, or drive the enemy away presented the most appropriate response. He ordered the two subordinate colonels, Fleming and his brother, Charles Lewis, to each detach 150 men led by the most experienced captains—giving little regard to company integrity—from their respective lines “to go in Quest of them.”32

Colonel Charles Lewis formed his detachment from the Augusta line with Captains John Dickinson, Benjamin Harrison, Samuel Wilson, and John Skidmore. Colonel Fleming assembled his with Captains Shelby and Russell of Fincastle, Captain Thomas Buford of Bedford, and Captain Philip Love of the Botetourt line. While the arrangement enabled the two lines to parade the most available soldiers quickly, the resulting loss of cohesion—and therefore combat efficiency—inherent in the ad hoc nature of the units soon negated any advantage. As Captain John Floyd later commented, “no one officer . . . had his own men.” Once formed into columns of two files, the two detachments marched “briskly” from opposite ends of the camp and beyond the line of pickets just after sunrise. Fleming’s Botetourt line detachment advanced about one hundred yards in from the Ohio River’s bank. Acting as the guide, Mooney took his place with the scouts to pilot the detachment to where he and Hughey had had their fateful encounter with the Indians. Colonel Charles Lewis’s detachment of the Augusta line advanced “near the foot of the hills” along Crooked Creek on a somewhat parallel course 150 to 200 yards east of and trailing Fleming by about 100 yards.33

Shawnee scouts detected and informed Cornstalk of the approaching Virginians. The chief realized the shots his warriors had fired at the hunters earlier had alerted the enemy to his army’s presence on Point Pleasant. Having lost the element of surprise, he altered his plan of attack. The Shawnee chief gave orders to initiate the battle by ambushing the two columns, keeping them separated and unable to provide each other mutual support. After they defeated the immediate threat, the warriors would continue the attack by advancing on the Virginia Southern Division’s main body to destroy it.

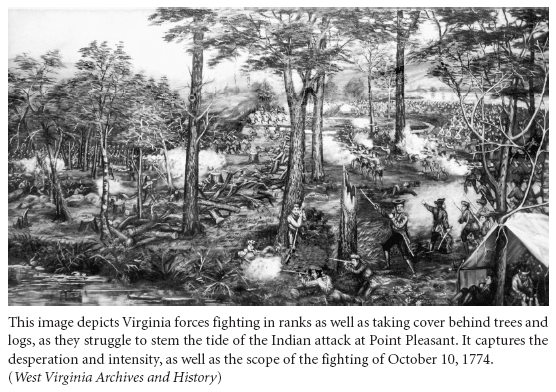

At about 6:30 A.M., as the Augusta detachment’s column began to cross an open area about one-half mile from the camp’s line of pickets, the men heard three shots fired in quick succession, which killed the leading scout. The woods ahead of them then erupted with a blast of musketry from Indian warriors positioned “behind Bushes & Trees.” Reloading quickly after the “first fire,” the Indians all fired another, and then a third shot as the Virginians struggled to deploy into line. The first man of each file stood fast as the next two split respectively to the left and right sides in succession, extending to form a single-rank line while taking advantage of any cover the vegetation provided. Given the nature of the terrain, the shock of enemy fire, and the tendency of inexperienced troops to stay close to comrades rather than in extended interval, it is unlikely that Lewis’s men occupied a line more than two hundred or three hundred yards long. The Augusta detachment fought back “with much bravery & Courage,” but the volume of enemy fire forced it back with several casualties.34

After pulling back, Lewis stood in the open, disregarding the cover a nearby tree provided. As he directed his captains while they re-formed the line on some high ground along Crooked Creek and attempted to tie in with Fleming’s line, a musket ball struck the colonel. He immediately realized the severity of the injury. Satisfied he had done all he could, he handed his rifle to his attendant, who then assisted him as he calmly walked back toward camp telling his men, “I am Wounded, but go on & be Brave.”35

Meanwhile, the Botetourt detachment had advanced about three-quarters of a mile beyond the pickets when Colonel Fleming heard gunfire on his right. “In almost a second of a minute,” his unit received fire from in front and also became heavily engaged. One of the first shots struck and killed Mooney, and the men deployed into line in the same manner as their Augusta comrades, except they did not initially also take cover. With their left flank on the bank of the Ohio, officers endeavored to get the men to extend the line so as to join their right flank to the left flank of Lewis’s Augusta line. Since Fleming’s detachment had moved farther up the point, they had to extend obliquely to the rear to join with that of Colonel Lewis. The men fought back with “with spirit & resolution,” but Fleming realized after several exchanges of fire that his men’s initial disposition “would never promise success.” Under the conditions, they were “forced to quit their ranks & fly to trees.”36

It is difficult to determine the frontage both detachments would have actually occupied. In addition to the factors already noted, both detachments suffered the consequences of the decision to draw men from every company to form them. Although he was not present, Captain Floyd later wrote that officers had difficulty in getting men to advance when the engagement first started because some troops refused to recognize the authority of any but the officers of their own companies. He added that the Virginians never had more than three hundred or four hundred men in action at once since a number of men avoided combat by sheltering behind “trees & logs the whole way” between camp and the fighting and “could not be prevailed upon to advance to where the fire was.” If these statements are true, the detachment frontages could have been considerably less than two hundred yards.

The Shawnees, Mingoes, and their allies enjoyed a numerical superiority and tactical advantage over both Virginia detachments in the opening stage of the battle. They fought with great bravery as they “Disputed the Ground with the Greatest Obstinacy” and pressed attacks that forced both lines of Virginians to retreat from one hundred to two hundred yards from the points where they made initial contact. At that critical moment, enemy bullets hit Colonel Fleming in three places and caused dangerous wounds. Two balls went through his left arm and broke both bones below the elbow, and one went through his left breast three inches below the nipple, which caused part of his lung to protrude. The colonel continued to encourage his men and remained on the field until he felt “effectually disabled” by the injuries. Assisted by one of his attendants, he returned to camp to seek medical care. Fleming later reflected that the Indians fought with such ferocity and skill that the battle “was attended with the death of some of our bravest officers & men, also the deaths of a great number of the enemy.”37

The Indians’ movements aimed to exploit the gap that separated the two Virginia detachments before they could join to form a continuous line. Feeling victory near at hand, some of the more impetuous warriors made rushes, “attended with dismal Yells & Screams,” against the Virginians, “often Running up to the Very Muzzles of our Guns where they as often fell Victims to their rage.” Fighting in pairs from natural cover, one member firing as the other loaded, the Virginians in both lines maintained a consistent level of fire. In this adaptation of conventional tactics to the woods, they took the tactical defense in which cohesive firepower eventually proved decisive. The surviving captains took charge. On the left, Captain Shelby assumed command from the wounded Colonel Fleming, and, ably assisted by Russell and Love, succeeded in halting the Botetourt line’s retreat. On the right, of all the captains, only Harrison remained uninjured to take command, but the situation remained desperate.38

Back at camp, the men listened to the sound of the battle that unfolded in the distance. They noted that the first few individual shots had erupted into an exchange of musketry on the right and then extended to the left as it increased in intensity. Casualties soon began to return to camp. Of the wounded field officers, Fleming arrived at the surgeon’s station where Dr. Watkins dressed his wounds. Although they were serious, the doctor believed they would heal. Colonel Charles Lewis reached the station just as the surgeon finished with Fleming. Watkins confirmed Lewis’s suspicion that his wound was mortal, and there was little a doctor could do except try to make his patient comfortable. Some men helped the dying colonel to his tent, where he expired a few hours later.

By 7:00 AM, the firing along the battlefront had become “very warm,” and the Virginia casualties mounted, particularly among the officers. With the initial detachments in trouble, giving ground, and in danger of getting outflanked, everyone concluded that they faced more than scouting parties. It had proved fortunate that the ill-fated hunting parties discovered the enemy and spoiled the element of surprise. What Colonel Andrew Lewis had intended as a reconnaissance-in-force mission against some scouts had become what is known in military parlance as a spoiling attack, a minor offensive action that disrupts the opponent’s major attack. In addition to the two injured colonels, walking wounded, and those who assisted other casualties, message runners informed Colonel Lewis of the gravity of the situation. Neither he nor anyone else had expected a general engagement at Point Pleasant, but he knew they now faced one with the two forward detachments driven back by the Indians’ initial onslaught. Since the Augusta detachment on the right had retreated farther, Colonel Lewis decided to send it an immediate and significant reinforcement first.39

The Augusta detachment had started the reconnaissance in force that morning trailing behind that of the Botetourt. The Indians had forced the Augusta detachment’s line to retreat a total of about four hundred yards since the first shots were fired, which put the critical fighting only a short distance from the camp; some participants said within sight of it. The Indians continued to press their attacks against the two detachments that had not yet joined to present a single continuous line of resistance. The gap between the two still represented a vulnerability the Indians might exploit if the Virginians could not close it.

With both of his subordinate colonels down, Colonel Andrew Lewis called on John Field. Although he had entered active service for this campaign in the grade (and pay) of major and commanding a three-company corps of volunteers, he held the permanent rank of colonel and the position of county lieutenant for Culpeper County. Lewis recognized Field in his permanent rank with the commensurate authority and ordered him to lead a reinforcement of two hundred men to stiffen and take command of the Augusta detachment’s line on the right of the battlefield. Once Field was in position, Lewis emphasized the need for him to extend the line to the left in an effort to join with the Botetourt detachment. Field went forward leading a composite battalion that included his own and Captain Kirtley’s Culpeper County companies, and the Augusta County companies of John Stuart, George Mathews, and Samuel McDowell, complemented by the remnants of the Augusta units whose captains deployed with Colonel Charles Lewis earlier in the day.

Colonel Andrew Lewis anticipated that on the right Cornstalk might also send a force down the bed of Crooked Creek to its mouth on the Kanawha. If the Indians succeeded, they would not only get around the flank of the Augusta detachment’s line and be in position to assail the Virginians’ camp, but they could cut off the Virginians’ retreat and seal the fate of the entire Southern Division. It became critical that Lewis get enough force along the creek on the right to stop such an enemy move. The colonel committed the last three Augusta County companies, about 120 men in all, to prevent the enemy from using the creek bed as an avenue of approach to the camp and to gain control of the key terrain of the adjoining high ground on the east bank. The companies commanded by Captains William Nalle and Joseph Haynes were ready and marched without delay, while Captain George Moffat’s company followed in short order. The two leading companies made contact with and engaged a party of the enemy in and astride the creek bed and forced the warriors to withdraw, while Moffat’s company ascended and took control of the elevation, which prevented the enemy from using it to get around the militia’s flank.40

While the engagement for the streambed ensued, Field and his reinforcement reached the battle line just in time to stem the Indian advance. The colonel directed the newly arrived companies into position to strengthen and extend the line to the left as the Virginians continued to fight on the tactical defensive. Summoning all the warriors they could, the Indian leaders made repeated brave and desperate attacks to break the Virginia line. All of their efforts proved futile, and according to Colonel Fleming, the “advantage of the place & the steadiness of the men defied their most furious Essays.”

Meanwhile, although holding their positions on the left, the Botetourt men also needed help. Colonel Andrew Lewis sent a runner with a message directing Captain Evan Shelby to assume command of the detachment. He then ordered a reinforcement to the line of about two hundred men. It consisted of the Botetourt County companies of Captains Matthew Arbuckle, Robert McClanahan, Henry Pauling, John Murray, and John Lewis, the last being Andrew and Charles’s nephew and cousin of his namesake in the Augusta line, plus the units commanded by the lieutenants who had remained in camp when their captains marched with Fleming.

Despite the desperate situation, Fleming noted that Colonel Andrew Lewis “behaved with the greatest Conduct & prudence and by timely & Opportunely supporting the lines” as he directed the battle. His coolness under pressure and tactical competence ultimately saved the Southern Division of the army from destruction and achieved the victory. That does not excuse his errors. The ability of the Indian army to approach so close to the camp at Point Pleasant without being detected nearly resulted in catastrophe. The plan for patrols and picket guards proved inadequate. The decision to muster some men out of each company and place them under command of the most experienced captains instead of committing entire companies to the two initial detachments had nearly led to defeat. It is therefore of great credit to the courageous officers still in the fight, and the brave men who followed them and acted like soldiers, that the Virginians were ultimately victorious.

Despite the earlier error, Lewis focused on the task before him. Throughout the rest of the battle, Fleming described his commander as “fully employed in Camp” as he sent companies to reinforce parts of the line where they were most needed and directed preparations for the defense of the camp in the event the Indians succeeded in pushing the army to the water’s edge. Until he committed their companies to the battle, the colonel instructed the captains who remained in camp to have their men working to clear the area between the two lines of tents and erect a breastwork using the trees and brush they removed. The sick, walking wounded, cattle and packhorse drivers, and all other men detailed “on command” from their companies took position behind the breastwork to defend the camp. Finally, Colonel Lewis held two companies in the rear. Captain Alexander McClanahan’s Augusta company, which provided that day’s camp guard and therefore constituted the final deployable reserve, and the Botetourt County company commanded by his eldest son, Captain John Lewis, which formed “a line round the Camp for its defense” behind which other companies could rally to make a final stand at the breastwork.41

Having “found their strength much increased” when Field arrived at the head of the reinforcements, the Augusta men on the right repulsed another attack and forced the Indians to retreat a short distance. Although the action remained “Extremely Hot,” the Indian forces no longer held a numerical advantage along the line of battle, and the Virginians wrested the initiative from them and advanced. The militiamen began to regain some of the ground they had yielded earlier in the day. At about 9:00 A.M., the Augusta line had advanced far enough forward for its leftmost unit to finally make contact with the Botetourt’s rightmost. As Colonel Christian later wrote, “Our People at last formed a line” of battle that ran continuously for about six hundred yards from the bank of the Ohio River on the west to Crooked Creek and the high ground on the east. The Ohio prevented the Indians from getting around the Virginians’ left flank, while the high, steep—almost vertical in places—ridge on the right offered no ground on which they could traverse around the Virginia right flank. Given the number of men committed to the fight and the length of the line, the Virginia companies could easily have formed the line two ranks deep. Even with an extended interval and men taking cover behind rocks and trees, the files of two riflemen each would have been one yard or less apart. Such a density optimized both the rate and volume of the Virginians’ aimed defensive fire against an enemy that either stood fast or advanced. From 9:00 A.M. to 1:00 P.M., the engagement became the kind of battle the Virginia troops had wanted to fight.42

The battle thus became static, but with no sign of slackening fire. In fact, the firing became even more intense as the opposing forces blasted away at each other at ranges of no more than twenty yards in some places. Along the line, some men fought individual combats, either with firearms, “tomahawking one another,” or hand to hand. Colonel Field became engaged in such a close-quarters fight. While he stood behind a tree waiting to acquire a target, an Indian warrior hiding behind a tree to his left front began to talk, which distracted him. With his attention thus diverted, two warriors positioned among some logs on higher ground to his right shot and killed him. With Field dead, Captain Shelby assumed command of the entire line of battle.43

Amid the sounds of gunfire and screams of the wounded and dying, soldiers heard their officers and sergeants shouting orders and words of encouragement. Those soldiers who understood Indian languages translated for their comrades as they heard chiefs and leading warriors similarly exhorting their own men to “drive the white dogs in,” “lie close and shoot,” “shoot straight,” and “be strong.” Those acquainted with Cornstalk heard his distinctive voice telling warriors to “fight and be strong!” All along the line, soldiers and warriors exchanged insults and epithets as well as bullets. Some recalled that their comrades who spoke Shawnee translated, and English-speaking warriors “Damn’d our men for white Sons of Bitches.” Other warriors taunted, referring to the field musicians playing their fifes in battle, asking why they did not “Whistle now” and saying that instead of playing they should “learn to shoot!” Other Indians yelled to inform their opponents of expected reinforcements in the night, and with the additional warriors they would again outnumber the Virginians when they finished the battle on Tuesday.

The engagement the Indians had initiated as a battle of annihilation, with a numerical superiority over Colonel Fleming’s and Charles Lewis’s detachments, had become a battle of attrition in which the Virginia soldiers now outnumbered Cornstalk’s warriors. The tide had turned slowly, beginning when Colonel Andrew Lewis committed most of his companies to the engagement. When suffering heavy casualties, Indian warriors generally broke contact in order to renew the fight under more advantageous conditions. At Point Pleasant, however, the Shawnees and their allies faced an unusual circumstance in that withdrawing at this time in order to fight again would cause them to face the combined Virginia army at a location even closer to the towns and cornfields they sought to defend. Withdrawal from this battle gained them no advantage and put them at greater disadvantage.44

Cornstalk decided to remain engaged at Point Pleasant in order to inflict more casualties on the enemy. The Indians would do so by allowing the Virginians to advance against a vigorous defense and pay dearly in blood for every foot gained. They would also feign retreat to lure into ambush or surprise small groups of advancing Virginians whom they had deceived into thinking the Indians were on the run. When the opportunity presented itself, they would renew the attack and break the Virginians’ line and destroy it.

Colonel Andrew Lewis gave Shelby the order to advance, and the troops pressed forward in a “fierce onset.” Weight of numbers eventually began to tell, and the Indians fell back “by degrees” for about one mile. To counter Indian ploys that sought to draw them into small-scale ambuscades, the Virginia officers endeavored to keep the men of their units in “one body,” according to Bland’s treatise, so they provided mutual support to each other as they advanced. The leaders took care to prevent part of a unit from getting separated from the main body, lest a small number of enemy destroy a larger unit piecemeal. To counter the Indian tactic of feigning retreat to lure the Virginians into an ambush, the Virginia officers adhered to Bland’s advice to prevent men from leaving their places in the line to go after the foe individually, or even allowing a few to pursue faster than the rest of the line advanced. Instead, they had men deliver covering fire for others who maneuvered forward, which subjected the enemy to “many brisk fires” that killed or wounded several of their chiefs and leading warriors.45

Although continuous, the volume of fire had decreased to the point that the officers considered it “not so heavy.” Despite the Virginians’ successful advance on the left side of the field, the terrain on the right, with its “Close underwood, many steep banks & Logs,” greatly favored the Indians in the defense as they disputed the ground “inch by inch” for about one mile. Between 1:00 and 2:00 P.M., in the course of their long retreat, the Indians “met with an advantageous piece of ground,” a long ridge about one and one-quarter mile east of the Ohio between a marsh and Crooked Creek, on which they could make a “resolute stand.” As a result, the Virginia line no longer ran straight across the point, but having advanced farther along the Ohio on the left, it skirted southeast then east along the base of the ridge to Crooked Creek. The Virginia officers made a reconnaissance of the Indian line and studied the terrain. They met in a council of war and determined it “imprudent” to attempt a frontal assault to “dislodge” the Indians.46

Between 3:00 and 4:00 P.M., the Virginians remarked on the decreased volume of the enemy fire and that the warriors began to appear “quite dispirited.” Officers speculated that the chiefs and leading warriors had vainly attempted to rally the braves and renew the fight. Throughout the battle, especially after the Indians began retreating, troops observed parties of warriors stopping to cut saplings to fashion into litters in order to remove the “dead, dying & wounded” from the battlefield. Although they recognized it as a common practice from previous battles, the militia officers were unaware of the details and extent of the evacuation until after the engagement. They had evidently carried wounded men back to the banked rafts and ferried them across. The Virginians found corpses hidden, buried, or “slightly covered” with earth, dead leaves, or foliage, and others that had been “drag’d down and thrown into the Ohio.” The fallen warriors who could not be carried off by their friends were intentionally scalped, presumably to deny the Virginians the trophies.

As part of the Indian force carried out the grim task and prepared to cross the Ohio, the other maintained a level of fire to prevent interference by the Virginians, and according to Major Ingles, “Continued Shooting now & then until night put an End to the Tragical Scene and left many a brave fellow Weltering in his Gore.”47 Colonel Fleming’s orderly book noted that besides hearing a shot “now & then” to discourage a pursuit, firing ceased at about one-half hour before sunset. The Indians then left the Virginians “in full possession of the field of Battle.”48 Under the cover of darkness, the warriors skillfully withdrew to where the rafts were located five or six miles upstream, crossed the Ohio with their wounded, and retreated toward Chillicothe.49

“Victory having now declared in our favor,” Colonel Lewis ordered the men to return to camp “in slow pace.” Along the way, they carefully searched for and recovered wounded to bring them into camp, “as well as,” Fleming added, “the Scalps of the Enemy.” It being too late in the day to publish the usual written plan and order, Colonel Andrew Lewis verbally ordered that the guard mount a force double the usual size for the night and designated “Victory” as the “Parole,” or password.50

Colonel Christian and his rear body were still twelve to fifteen miles from the mouth of the Kanawha when the battle started. He had planned to reach the camp at the mouth of the Kanawha sometime on Tuesday until he received an urgent message from Colonel Andrew Lewis. Informed that the camp was under attack, Lewis ordered Christian to come as quickly as possible. Christian left a small guard detail to remain with the cattle and packhorses and to follow as best they could while he led most of the men forward to Point Pleasant. Privates Joseph Duncan and John W. Howe recalled, “We left the Cattle and marched on to join the battle” but arrived too late, after the battle had “terminated.” Captain Floyd recalled that Christian’s men marched into camp at about midnight, when they “were kindly received” and told that their arrival had been “much prayed for that day.” When the follow-on detachment with the cattle and pack train finally reached Point Pleasant on Wednesday, Private James Brown said they “helped to bury the dead, and attended the wounded & then stayed a considerable time on duty.”51

When he saw the condition of the dead and wounded, Colonel Christian predicted that many more men would die. Not only did many have two or three gunshot wounds, the colonel added that the casualties were in a “deplorable situation,” with “bad doctors, few medicines, nothing to eat or dress with proper.” Even more horrifying, Christian remarked that the cries of the wounded prevented the uninjured but exhausted men from resting at all that night.52

Fleming described the engagement as “a hard fought Battle” that lasted from sunrise to sunset. While Colonel Andrew Lewis’s wing of the army retained the field, it had suffered 75 killed or mortally wounded and 140 wounded of varying severity, with many shot in two places, and some in three. Having started the engagement with nine hundred effective officers and men, the army sustained a casualty rate of about 20 percent, with an extraordinarily high proportion among the officers. These included the two colonels, four captains, and four lieutenants dead. The wounded officers counted one colonel, three captains, and three lieutenants.53 The Virginians had the “satisfaction” of carrying all their wounded and dead off the battlefield “with Very little Loss of Scalps,” while taking about twenty scalps from the enemy.54

An exact number of Indian casualties cannot be determined because of their practice of carrying their wounded and dead off the battlefield and disposing of the remains of the latter. Most Virginia participants believed the enemy had suffered an equal number of dead and wounded, but one can reasonably argue that they had fewer casualties. The only indication as to what the battle had cost the Shawnees and their allies rested in what the Virginians found on the battlefield. Major Ingles reported that the Virginia troops took twenty scalps. Two days after the engagement, on Wednesday, October 12, Colonel Fleming enumerated seventeen scalps that the men had collected and “dressed hung upon a pole near the river.” The plunder taken on the field included “23 Guns, 80 Blankets, 27 Tomahawks,” and assorted “Match coats, Skins, Shot pouches, powder horns, War clubs, &c.” Fleming recorded that the plunder “sold by Vendue accounted to near £100.”55

The battle may have ended but not the war. The men at Point Pleasant expected another engagement, if not there, then when they joined forces with Lord Dunmore. The day after the engagement, heavy patrols searched for Indians within several miles, and Colonel Christian’s men located the rafts where the warriors had ferried across the river. Back in camp, with a double guard still mounted, the officers began the process of preparing the Southern Division to continue its mission. All company commanders inspected their men, arms, and ammunition. They then issued a sufficient amount that “completed” each soldier’s load to “1/4 lb. Powder & 1/2 lb. Lead as early as possible.” The officers then held their units “in readiness” so they could take the field as well as “well repulse” another enemy attack while they gathered the beeves and completed construction of the post at Point Pleasant.56 Colonel Lewis composed a message to the governor that gave him details of the engagement. He also requested that in view of the recent battle, Dunmore consider marching the Northern Division to Point Pleasant before he advanced against the Shawnee towns. If Dunmore did not concur, Lewis requested that he send a surgeon to assist Dr. Watkins and medicine to help treat the Southern Division’s wounded.

Colonel Lewis took the time to commend his men. He asked his subordinate officers to pass on his “Hearty thanks . . . to the brave officers & men who distinguished themselves” in the previous day’s battle, and commended their gallant behavior in “a Victory . . . under God obtain’d.” The army took time to mourn its losses. Recognizing the high number of casualties, Lewis urged his men not to be dismayed by the deaths of so many brave officers and soldiers. Although they could not help regretting the casualties, the colonel urged that they use the memory of the fallen to inspire them “with a double degree of Courage and Earnest desire to give our perfidious Enemies one thorough Scourge.” The army buried the men who died in the battle in different places and interred the “officers & Gentlemen in the Magazine.”57

In the aftermath of the fighting, Virginia officers and soldiers offered a grudging respect for their opponents. Colonel Christian, for example, recorded that the officers to whom he spoke after the battle described that “the Enemy behaved with inconceivable Bravery” and “exceeded every man’s expectations.” Fleming said, “Never did Indians stick closer to it, nor behave bolder.” He also added that the warriors “came fully convinced they would beat us.”58