Introduction

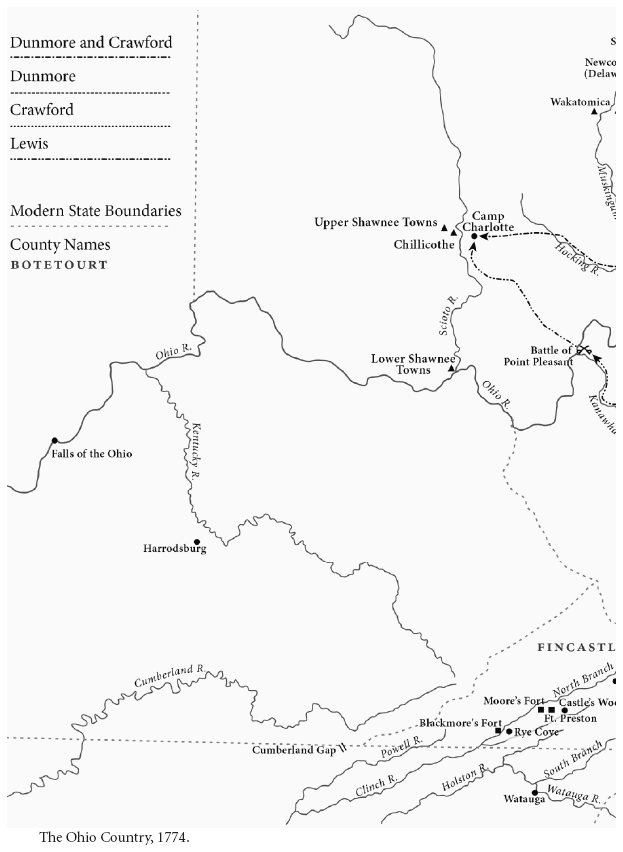

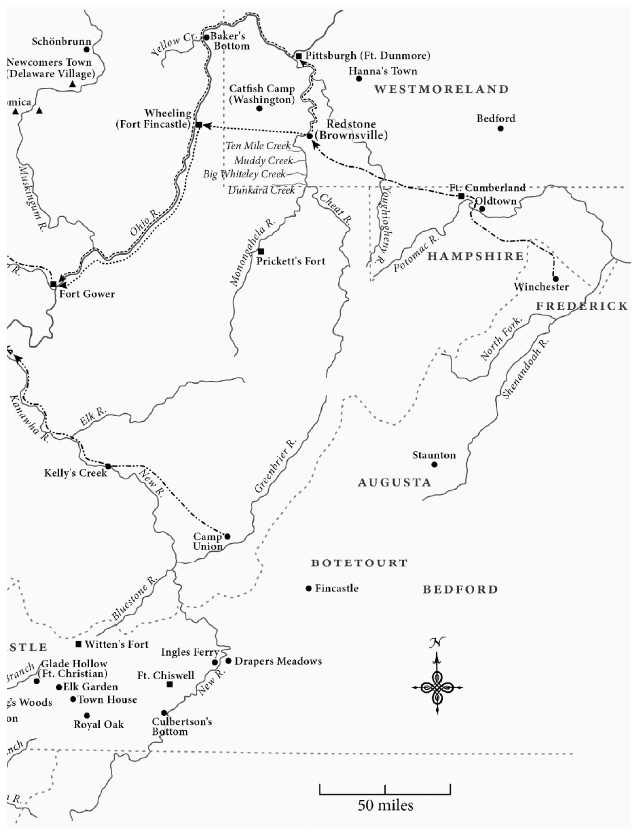

DUNMORE’S WAR, named for the last royal governor of Virginia, John Murray, fourth Earl of Dunmore, was the final Indian conflict of America’s colonial era. Set mostly in the mountains, valleys, and farmlands of the Virginia backcountry and Ohio River valley from April to November 1774, the conflict started when Indian war parties initiated an aggressive campaign of vengeance with small-scale attacks and raids against homes and settlements on Virginia’s frontier. By June 10, after passive defensive measures on the part of local militia failed to stem the violence, Governor Dunmore directed the county lieutenants to respond more vigorously, including limited offensive action. On July 12, the governor took the field to assume personal command. He planned a coordinated response with the combined forces of the most affected counties to take the war to the Shawnee and Mingo towns. About two thousand five hundred militia soldiers, not counting those who remained behind to guard the settlements, marched against approximately one thousand defending Indian warriors, mostly Shawnees, not counting those raiding the backcountry at large. The campaign resulted in only one, but decisive, large engagement in October. By November, the Indian leaders sued for peace and accepted the terms that Lord Dunmore proposed in order to spare their towns from destruction.

This book is, in the main, a campaign history that examines the military operations of Lord Dunmore’s War. But it also takes into account diplomatic efforts and political factors. It shows that Virginia called on its colonial militia to achieve strategic objectives consistent with the justified defense of the province and provisions of its royal charter. Furthermore, the narrative demonstrates that the colonial Virginia militia was a more competent military organization than is often portrayed.

Relying almost exclusively on primary sources, the narrative places the 1774 conflict in the context of pre-Revolutionary War Virginia and addresses several themes. First, Governor Dunmore acted in what colonists perceived were the best interests of the colony. As a result, his policies were generally popular and earned him the admiration of those he governed. At times, however, they conflicted with those of the British government and put him at odds with the Secretariat of State for the Colonies, also called the Colonial Office, the ministerial department to which he reported and from which he received his orders and instructions. Second, an Indian war in the Ohio country had become inevitable in early 1774, and the Shawnees represented the nation with the most hostility toward the British and colonial westward expansion. While Dunmore received at least nominal support from the British Indian Department, he took an active and direct role in diplomacy with the various native peoples living in the Ohio valley and bordering his colony. Third, the Virginia governor led his colony’s forces in defense of what they viewed as legally acquired territory and demanded no further land concessions from those they defeated. Fourth, the narrative presents a detailed examination of the organization, training, tactical doctrine, and operations of Virginia’s colonial militia, which challenges many popularly held beliefs. Fifth, and finally, Virginia’s victory in Dunmore’s War held important implications for both sides in the American War of Independence, especially with regard to Indian participation.

Overshadowed by the Revolutionary War, which began six months after it ended, Dunmore’s War remains understudied and largely misunderstood. Many historians have either relegated it to the status of a footnote or briefly summarized the episode as a prelude to the Revolutionary War. This is unfortunate because the war is an intrinsically interesting subject with significance in its own right, and its namesake, Lord Dunmore, is a major historical figure.

Many of the currently available histories explain the conflict as little more than an attempt to wrest land from aboriginal inhabitants, and vilify Virginia settlers in general and Lord Dunmore in particular. Others describe it as either a relatively unimportant preliminary to, or an intentional diversion of attention from, events occurring at the same time in Boston and Philadelphia that signaled the approaching revolution. In contrast, this book shows that Virginia called on the colonial militia to defend its border from invasion and secure strategic objectives consistent with the legal acquisition of land and its royal charter. The causes and conduct of the Indian war were not directly connected to origins of the struggle for American independence. However, the results of Dunmore’s War held important consequences that manifested themselves early and throughout that approaching conflict.

Various histories of the period that mention Dunmore’s War, especially if written since the late twentieth century, almost universally characterize Virginia as the aggressor and its soldiers as land-hungry opportunists at best or lawless and racist banditti at worst. The primary sources cited to support that conclusion reflect the less-than-objective perspective of participants who favored the interests of Pennsylvania in its 1774 boundary dispute and competition for dominance of the Indian trade with Virginia. The different views found in Virginia records and the writings of Virginia participants have been largely ignored, marginalized, or dismissed as “triumphalist” in much of the recent scholarship.

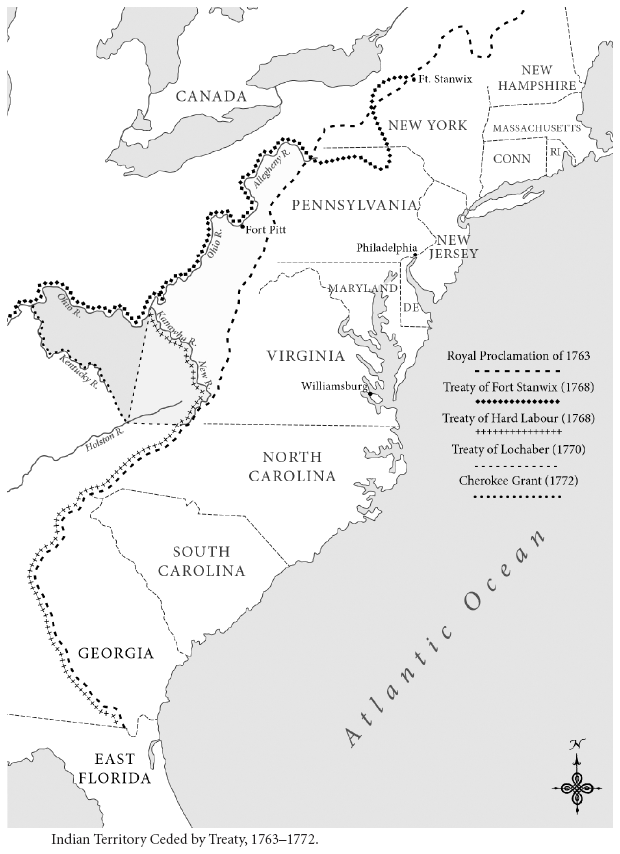

Without ignoring the evidence that has provided the basis of opposing interpretations, this book primarily studies the situation as Virginians recorded it. The documentary evidence from those sources shows that the colony’s government did not base its policies only on self-serving aggression. Virginia’s acquisition of Indian land between 1768 and 1772 met the established legal requirements, conformed to the restrictions set forth in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and were ratified by the British Crown. Virginia’s expansion into the newly ceded land was allowed by law, as contemporary Virginians and government officials viewed it, and reflected the tenets of Enlightenment philosophy on the settlement of new land.

Many authors cast the Shawnees in the role of innocent victims. While the statement contains a basis in fact, it does not consider the hostile actions committed against Virginians by bands of Shawnee warriors that preceded or precipitated the conflict. Other historians have similarly blamed the war on Virginia aggression and described the Shawnees as trying to protect their homeland in the face of unauthorized white encroachment. When put another way, perhaps without realizing it, the same authors affirm that the Shawnees acted in their own national interests, as any polity would—including the Virginia colony. Similar interpretations fail to mention that the Six Nations, or Iroquois Confederacy, ceded Shawnee hunting ground to the British as part of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. The omission maintains the focus on the dispute between the Shawnees and Virginians without an explanation of the Iroquois Confederacy’s involvement in creating the contentious situation. The significance of Six Nations suzerainty over other native peoples is essential to a complete understanding of the situation on the frontier in 1774 and the causes of Dunmore’s War, and is addressed in detail in this book.

Some historians argue that Virginia sought to fight a war of conquest against Indians, and it mattered little which nation or tribe, in order to take their land. To support that contention, they argue that Dunmore and other Virginians initially viewed the Cherokees as their next target, but then used the raids of the Mingo-leading warrior known as Logan as an excuse to go to war against the Shawnees. Dunmore’s War, in contrast, shows that Logan’s faction of Mingoes had already allied itself with those Shawnees who were predisposed to war. Another interpretation often taken by some historians maintains that after Virginians understood that defeating the Cherokees would not serve their purpose of expansion, they changed their story about Cherokee hostility and provoked the Shawnees into a war instead. The review of primary sources for this book reflects the error in such interpretations. It shows that Shawnee war parties had not only raided backcountry settlements before some infamous Virginia ruffians—not organized as militia—massacred Logan’s family, but continued to do so as the Mingo retaliated, while Virginia and Cherokee leaders attempted to resolve their separate dispute peacefully at the same time.

Careful analysis of the comprehensive survey of sources cited in this narrative supports the position that Virginia’s soldiers primarily fought a defensive war against unprovoked Shawnee and Mingo attacks on the south bank of the Ohio. Dunmore resorted to conducting an offensive operation only after it appeared to offer the most militarily and cost-effective means to end the war and secure the frontier as soon as possible. It was for this reason that he ordered the militia into the colony’s service in July 1774. This book also shows that interpretations that explain that greed—the desire to take booty and Indian land—do not accurately characterize average soldiers’ or officers’ motivation to serve on Dunmore’s expedition. The taking of what one author described as “booty” referred to the possibility of taking Indian horses as an enticement for recruits to join the expedition. Horses represented military resources and therefore legitimate spoils of war, or plunder, to which the victor was entitled according to the conventions of eighteenth-century warfare. Indian raiders certainly sought every opportunity to acquire horses by seizing them from Virginians. While the terms booty and plunder are often used interchangeably today, a researcher should consider eighteenth-century usage by consulting Samuel Johnson’s or other period dictionaries. Choosing the more pejorative booty—connoting goods taken by robbery, rather than plunder, for spoils taken in war—although possibly unintentional, casts Virginia soldiers in the role of the aggressor.

Perhaps the strongest evidence to support the thesis that Dunmore and the Virginians fought a defensive war is found in its conclusion. When the expedition proved successful in bringing the hostile Indians to negotiate terms, the war-ending Treaty of Camp Charlotte proved far less draconian than one would expect from an aggressor bent on land acquisition through conquest and genocidal extermination. Although Dunmore demanded that the Shawnees and Mingoes return all captives, including those they had never repatriated at the end of Pontiac’s War a decade earlier, he required no cession or encroachment of their homeland. The peace terms affirmed the Ohio River as the boundary between the Virginia colony and the land reserved to the Shawnees according to the treaties Crown authorities had negotiated with the Iroquois in 1768 and the Cherokees in 1768 and 1770, but made no demand for a deed to Kentucky from the Shawnees. The surrender of several chiefs or leading warriors to serve as hostages represented the sternest measure Dunmore demanded. A common practice in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Indian diplomacy, the surrender of hostages served as security that the Shawnees would honor their promise to release all of their white and black prisoners, as well as guarantee that their headmen would meet Virginia commissioners to sign the final treaty at Pittsburgh the following spring. The defeated party met the condition to demonstrate a sincere desire to negotiate a lasting peace treaty and show the victor that it was not using an armistice in order to disengage from a losing battle so it could renew hostilities later.

Previous treatments of the military institutional aspects of Dunmore’s War have been no less unsatisfactory. Like the explanations of the causes and precipitating events, the available literature includes many inaccurate, albeit oft-repeated or broadly interpreted general descriptions of the Virginia forces, with little attention paid to military operations and tactics. In contrast, the pages that follow present a complete and detailed operational account with due consideration of military practice and organization.

The authors who do address the tactical operations attribute any success Virginia militiamen enjoyed to their adopting or copying the tactics of their Indian adversaries, an oversimplification. The reader of this book will see the militia’s success resulted more from adapting British tactical doctrine to North America rather than simply adopting Indian fighting methods. Both of Dunmore’s principal subordinates, Colonels Andrew Lewis and Adam Stephen, as well as a number of the other officers, had served in Colonel George Washington’s 1st Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. Stephen, like Washington, had survived Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela in 1755. Such officers learned that victory over Indian enemies came by combining regular and irregular tactics, and they trained their men accordingly. The evidence related in the narrative that follows shows that under the tutelage of veteran officers, colonial militiamen had read instructional texts such as Humphrey Bland’s Treatise on Military Discipline and applied the lessons about fighting irregulars in Europe to their own experiences fighting Indians. It is important to note, however, that Bland’s instructions could not simply be used as written but had to be modified and adapted to the conditions and enemies encountered in North America.

The Virginians adapted conventional European tactics to the American woods and blended them with techniques learned from their native allies and adversaries, as well as the experience of previous conflicts, into their own brand of bush fighting or skirmishing. Virginia’s colonial soldiers achieved success in battle against Indian enemies by adhering to a modified British doctrine, which emphasized unit cohesion and fire superiority, although not necessarily by fighting in compact ranks and shunning natural cover, and combined the strategic offense and tactical defense. Similarly, Indian warriors nearly abandoned their traditional tactical doctrine at the Battle of Point Pleasant. Their general practice usually dictated fighting a battle of annihilation rather than one of attrition. The plan of Cornstalk, the Shawnee chief, to advance en masse seeking to surprise, overwhelm, and destroy the opponent in a quick victory was in keeping with this practice. When the attack failed to achieve the desired outcome, Indian forces surprisingly conducted a battle of attrition for several hours before the Shawnees finally disengaged and retired. In addition, the reader will see Virginia’s colonial militia as a much more efficient military organization than it has often been portrayed. The army involved in the 1774 campaign likewise effectively followed British—or European—logistical procedures, appropriately adapted to operations in North America, with the protected advance to sustain its forces in the field throughout the campaign.

Much of the currently available literature does not present a completely accurate portrayal of the composition, organization, and training of Virginia’s colonial militia. Some authors, for example, explain that the county militias of Virginia were mirror images of those organized in English counties. Although accurate in a general sense, the statement omits the very important distinctions that existed between the Virginia and English militias despite their common heritage. For example, an English parish filled its portion of the county’s quota by ballot, or draft, after which the selected men served terms of three years. Following a period of initial training, the militia man joined a unit that mustered periodically and could respond to local alarms or augment the regular British army for homeland defense during emergencies. In contrast, unless exempt by law, all free white male Virginians age eighteen to forty-five had an obligation to serve. They all trained periodically and served whenever the county or colony called them for military service.

Other treatments of Dunmore’s War have also tended to impose a formal regimental structure on the administrative organization of Virginia county militias. The reader of the following narrative will note that the administrative groupings of the Virginia militia actually bore less resemblance to such a regular tactical organization. An oft-repeated error is that members enlisted to serve in the militia, and the expedition of 1774 experienced no recruiting problems. The reader of this book will not only gain a more accurate understanding of service in the Virginia colonial militia in general but will also note the difficulty officials encountered when raising forces needed for active duty.

The evidence presented in the following pages shows that the county lieutenants followed the requirements of the colony’s militia law and the procedures established for defending their own and assisting neighboring communities, as well as the province at large. It further establishes that the militia of the Virginia colony existed as a pool of available manpower that county, independent borough, or provincial governments could mobilize for military service. The local companies and county regiments constituted administrative—not tactical—units organized according to regional population densities and not mission-oriented considerations. The governor appointed all company officers based on the recommendations of their respective county lieutenants. The governor also signed and issued commissions to the men who the county officials recommended to raise and lead tactical units and authorized them to recruit volunteers and draft individuals to fill their ranks. Ideally, a company embodied for actual service was organized with fifty rank-and-file men, plus officers, sergeants, and musicians, along lines similar to, but not exactly like, those in the British army. While not on a level equal to that found in the regular army, the men of the Virginia militia nevertheless submitted to a level of discipline often not reflected in the popular view of frontier Americans.

Many of the available interpretations depict the Virginia General Assembly as unwilling to support Dunmore with an appropriation of funds and authorization for military action against the hostile Indians. Primary evidence found only in the Pennsylvania records would tend to support such conclusions. The Virginia records contain contradictory testimony. This book demonstrates that although the General Assembly did not agree with Dunmore that the situation warranted the appropriation of funds and authorization to raise an army of provincial regulars, Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses, offered a more appropriate recommendation. Randolph informed the governor that the law titled An Act for Reducing the Several Acts of Assembly, for Making Provision against Invasions and Insurrections, into One Act (often shortened to Invasions and Insurrections Act) already gave him the authority to call militia into service and employ them in this kind of emergency without additional legislation. Perhaps other historians mistook the speaker’s explanation that the act for provision against invasions and insurrections constituted a more appropriate application of the governor’s war powers for dealing with the emergency as a refusal to act. The reader will also learn that according to the law, the colony’s General Assembly normally appropriated the money after the emergency ended and reimbursed military expenses and paid militia soldiers for their service in arrears, not in advance. The record shows that the Virginia government followed the established procedure when it paid its soldiers and the related expenses for the Indian campaign in July 1775, albeit after the Revolutionary War began and Dunmore had fled Williamsburg.

The events related in the following pages occurred during a period in colonial America when resistance to certain British imperial policies had not yet risen to a struggle for independence. Although the Revolutionary War is not the subject of this book, Dunmore’s War had an important influence on the events of that later conflict. As long as both sides adhered to the terms of the Treaty of Camp Charlotte and the subsequent councils held at Fort Pitt in 1775 and 1776, the Ohio frontier remained relatively peaceful. Combined with the respite from fighting that ensued in the east between the British evacuation of Boston and the invasion of New York in 1776, the Americans had sufficient time to decide in favor of and declare their independence. When Cornstalk announced the Shawnees’ decision to enter the war as British allies and resume hostilities in November 1777, it presented Virginia the motive and opportunity to invade the north bank of the Ohio as a component of the greater struggle. American success in that theater resulted in Britain’s recognition of the Northwest Territory, encompassing the present states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan as within the territorial boundaries of the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.