APPENDIX

Human Progress

This book rests on a few core arguments. They are:

• We are living in an unnaturally prosperous time. Our prosperity is not merely material but political and philosophical. We live in a miraculous time, by historical standards, where every human born is recognized by law and culture as a sovereign individual with inalienable rights. This is not normal in humanity’s natural environment. It is, to use the label I have used throughout this book, a Miracle.

• We stumbled into this Miracle without intending to, and we can stumble out of it.

• Human nature not only exists but is fundamentally unchanging.

• If we do not account for and channel human nature, it will overpower and corrupt the institutions that make prosperity possible.

The easiest of these propositions to demonstrate is that we are living in a uniquely prosperous time. It may seem obvious to some, but this “Great Fact,” as Deirdre McCloskey calls it, is denied, denigrated, or dismissed by many. Ironically, the Great Fact is demeaned most vehemently by those who believe that material conditions—i.e., economics—represent the heart of political morality. The very essence of socialism—in all of its myriad flavors—is the dogmatic conviction that the virtue of society is determined almost entirely by how fairly wealth and resources are distributed.

This is an entirely legitimate and defensible worldview. But it has practical problems when turned into public policy. As Margaret Thatcher liked to say, “The problem with socialism is you eventually run out of other people’s money.”1 We’ll deal with those issues later. There’s another more fundamental problem that needs to be dealt with here. All forms of socialism—in the broadest sense—subscribe to an entirely subjective understanding of poverty. The poorest among us are measured against the richest among us. In other words, when poverty is defined subjectively, a millionaire is poor in a community of billionaires. If one considers poverty to be an objective condition instead of a relative one, the poorest among us live better than the richest in our natural environment. One could quibble with this by pointing to the plight of some homeless people, but the average member of the working poor in the United States in 2018 lives better by any imaginable material measure than the wealthiest human a thousand years ago. And by many measures, a typical poor person today lives better than a rich person even a hundred years ago.

This is not an argument for saying we shouldn’t do more to help poor people today. It is merely an observation that our standards are so contingent and time-bound that we often lose sight of the mind-boggling progress we’ve made in a remarkably short period of time. This appendix is intended to demonstrate that progress.

If the time line of human history were a landscape, humans lived in a wasteland for most of it, living off the land, eating tubers, acorns, bugs, and small mammals. “The most important thing to know about prehistoric humans,” writes Yuval Noah Harari, “is that they were insignificant animals with no more impact on their environment than gorillas, fireflies or jellyfish.”2 It was only recently that humans became the apex predator on this planet. Our species only started hunting at all about 400,000 years ago, and long after that our prehistoric ancestors were as likely to be hunted as to hunt. Many of our first tools were used to crack open bones to get the marrow. According to some experts, that may have been our niche. “Just as woodpeckers specialize in extracting insects from the trunks of trees,” Harari suggests, “the first humans specialized in extracting marrow from bones. This is because the first members of genus Homo were scavengers, picking over the abandoned kills of superior predators.3

It probably isn’t necessary to dwell on the poverty of our pre-Homo sapiens forebears. So let us fast-forward a few hundred thousand years to consider the Yanomamö, a tribe living on the banks of the Orinoco River along the border of Brazil and Venezuela. They are one of the few stone-tool-making hunter-gatherer societies left in the world. They live mostly off subsistence hunting, small-garden agriculture, and a little trade; some Yanomamö make baskets, hammocks, and other items to sell to nearby villages.

In a very rough estimate by Eric Beinhocker, the Yanomamö make on average about $90 a year. (It has to be a rough estimate, Beinhocker notes, because the Yanomamö don’t use money, never mind compile statistics.) According to Beinhocker, “It took about 2,485,000 years, or 99.4 percent, of our economic history to go from the first tools to the hunter-gather level of economic and social sophistication typified by the Yanomamö.”4 In other words, for nearly all of human history, the Yanomamö would be considered incredibly rich. As economist Todd Buchholz puts it, “For most of man’s life on earth, he has lived no better on two legs than he had on four.”5

But by modern, official metrics, the Yanomamö are worse than poor. The World Bank defines poverty as living on $1.90 per day.6 Again, putting this in terms of money is a bit misleading, but it captures the material poverty of subsistence or near-subsistence living that defined human habitats for almost all of human history. It should also go without saying that the Yanomamö live without access to health care. A trivial injury for you or me can be a death sentence for them. Yanomamö poverty also encompasses the fact that the typical tribesman faces a paucity of choices about how to spend his or her life. If you subscribe to some “noble savage” nostrums or believe that ignorance is bliss, you might think they have a good deal. Who needs to study art or literature or practice medicine when you can live an “authentic” life of hunting, gathering, and basketmaking? But that option is more or less available to everyone reading this book, and yet you are not heading out for the wilderness.

While the readers of this book live in the oasis of the now, the Yanomamö still live on the outskirts of it.

After the onset of the agricultural revolution, it took about 12,000 years for humans to go from the $90-a-year Yanomamö standard of living to that of the ancient Greeks in 1000 B.C. ($150-a-year), according to economist J. Bradford DeLong. And it wasn’t until A.D. 1750 that income reached $180 per year—a doubling of income from Yanomamö standards, yes…but over nearly 14,000 years.7 Economic historian David S. Landes was not exaggerating when he said that “the Englishman of 1750 was closer in material things to Caesar’s legionnaires than to his own great-grandchildren.”8 Douglass C. North and his colleagues write in Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History that “over the long stretch of human history before 1800, the evidence suggests that the long-run rate of growth of per capita income was very close to zero.”9

In other words, if the 200,000-year life span of Homo sapiens were a single year, the vast majority of human economic progress would have transpired in roughly the last fourteen hours.10

The spoiler, of course, is that no one truly knows why the Miracle happened. There are many theories but no consensus. The best explanation is that ideas changed. Starting in the 1700s, in a remote corner of Europe, people started to believe that the individual was sovereign, that innovation was good, that the fruits of our labors belong to us. We invented the notion of God-given rights and a way to organize the larger society—the extended order outside of family and tribe—that allowed humans to trade and make contracts rather than club each other. We stumbled into a non-zero-sum system that made people freer and wealthier. I have called this the Lockean Revolution, but John Locke no more created it than Adam Smith created capitalism when he described it.

I should pause here to explain that my aim in this appendix—or to some extent even in this book—is not to offer an explanation for why the Miracle happened but merely to demonstrate that it happened at all. From the vantage point of human history, this explosion of prosperity is as miraculous as the goose that lays the golden egg waddling into a peasant’s home and producing unimagined wealth. I have already laid out the different theories about the why. But the what is what matters here.

The Chinese have a useful concept: “the rectification of the names.” Confucius argued that when words no longer describe the world as it is, justice becomes impossible. “If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things,” Confucius wrote. “If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.”11

The age we live in is disconnected from the past. That is a good thing. That, in fact, is the Miracle. But there is a downside. When you amputate historical memory, you end up taking the present for granted. If you were born and raised in an oasis, you would be forgiven for not appreciating the misery of living in the desert. Westerners act as if the prosperity of today is simply natural, and, as a result, they have a cavalier attitude toward the ideas and institutions that make our prosperity possible. Recognizing our good fortune is the first step in securing it for posterity. The average American and West European lives the most bespoke lifestyle in human history, and yet we are angry that it is not even more tailored to our desires. In short, we are ungrateful. And in our ingratitude we indulge the devil on our shoulder that is human nature.

Unless you are reading this naked in the woods, nothing around you right now is natural. It is artificial. It is manufactured. And it is wonderful. But we refuse to see it that way. As Irving Kristol said, “When we lack the will to see things as they really are, there is nothing so mystifying as the obvious.”12 So let me return to demystifying the obvious.

According to economic historian Angus Maddison, the Western world’s economy from A.D. 1 to A.D. 1820 grew at 0.06 percent per year, or 6 percent per century—that is, essentially no growth at all.13 World per capita GDP rose from $467 in A.D. 1 to a mere $666 in 1820.14 Deirdre McCloskey estimates that, prior to the Industrial Revolution, pretty much everybody lived on about $3 a day.15 In material terms, even the marginally more fortunate lords and barons lived closer to what we would today call a subsistence lifestyle. Virtually everyone throughout most of human history has lived in what we today have the luxury of calling poverty.

Economic growth took off in the 1700s, starting in England, and has been accelerating ever since.16 Maddison estimates that the goods and services produced between 2001 and 2010 constitute 25 percent of all goods and services produced since A.D. 1.17 McCloskey’s figures put the difference between what our ancestors lived on and what we live on today as that between $3 and $100 a day (for bourgeois nations).18 J. Bradford DeLong finds a thirty-seven-fold increase in world per capita income from 1750 to the late 2000s, from $180 per person to $6,600 per person.19 And even the modern world’s poorest places experience growth rates unlike anything before the Industrial Revolution.20 Global GDP has soared, from an estimated $150 billion in A.D. 1 to more than $50 trillion as of 2008.21 Observed macroscopically, we are closer to Eden than Eden ever was.

The Bernie Sanders chorus would not dispute this: They recognize that enormous wealth has been accumulated. They merely argue that the poor have been left behind. That’s false. In the great migration out of the desert of time, the poor may have been at the back of the caravan, but they have lived in the oasis too. And as the West has marched deeper into the oasis, more of the world has followed us into it.

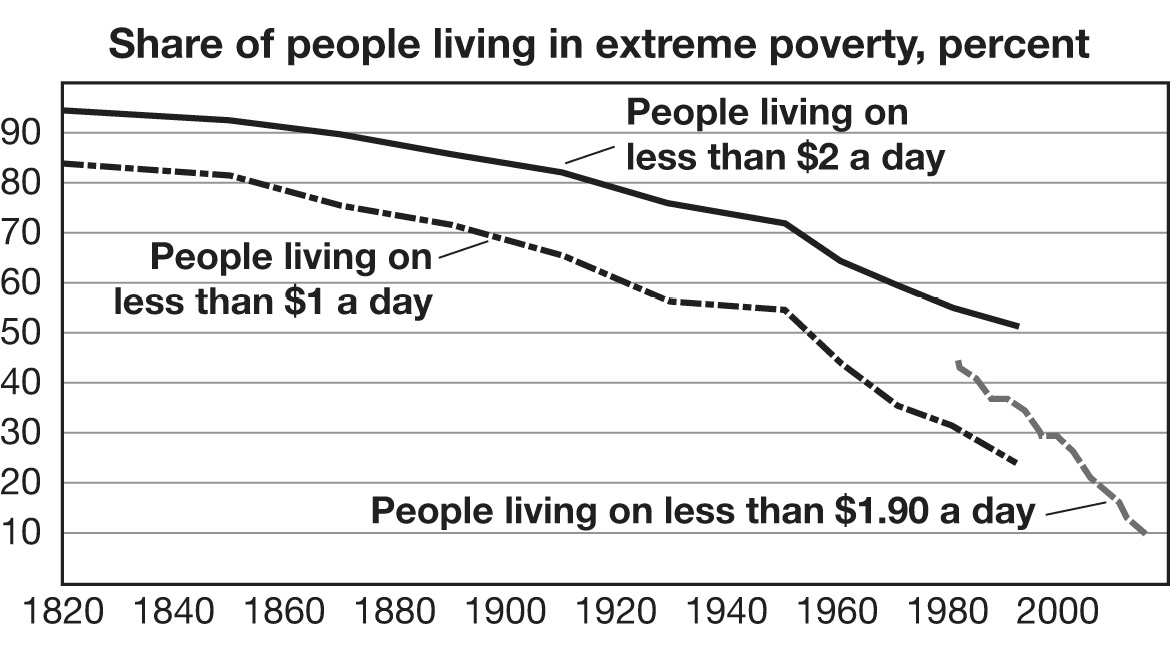

Around the world, the number of people considered poor has decreased both relatively and absolutely—an incredible feat, given massive increases in population.22 For all of human history before the modern era, what we call poverty was simply the Way Things Are. It remained so in most of the world as recently as 1820. By one dire account, in 1820, 94.4 percent of the world’s population lived on the equivalent of less than $2 a day, and 83.9 percent lived on less than $1 a day that year. As of 2015, only 9.6 percent of the world’s population lived on less than $1.90 a day.23

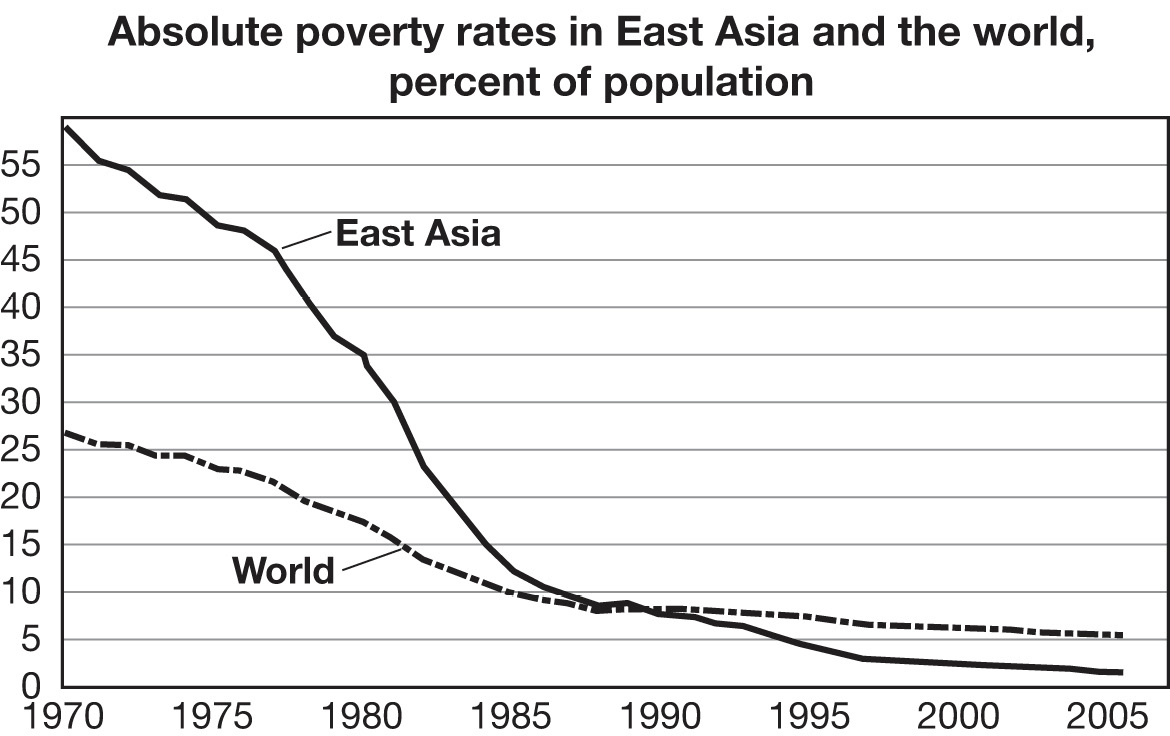

The figures are even more impressive in raw numerical terms. As recently as 1970, almost 27 percent of people worldwide lived in absolute poverty (less than one 1987 dollar a day). A little more than 5 percent did as of 2006.24

Decry “globalization” all you like. It certainly has come at a price for some citizens of the developed world. But the spread of market forces to the far corners of the globe has been the chief driver of the largest eradication of poverty in human history. Between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of the population in developing countries living in poverty fell from 43 to 21 percent, a reduction of almost one billion people.25 In 2015, for the first time in human history, less than 10 percent of the world’s population was considered extremely poor.26 The United Nations estimates more poverty was reduced in the last fifty years than in the previous five hundred.27

One of the great cleavages between left and right is a disagreement over the definition of freedom. The left tends to define freedom in material terms, the right in political ones. FDR argued that “necessitous men are not free men.”28 Thus the state must provide or guarantee health care, income (or employment), etc. This is so-called positive liberty. The right prefers “negative liberty”—freedom from government interference. What often gets left out of the debate is the fact that economic growth and technological innovation do more to provide positive liberty than any government possibly could.

The ultimate finite resource is time. Technology cannot create more hours in the day, but it allows us to do more with the hours we have by reducing the amount of labor required to accomplish desired tasks. One of the dominant aspects of a precapitalist, preindustrial world was the sheer amount of work required to perform even the most menial tasks, and the staggering number of workers required to perform them. Today’s world is increasingly leaving the burdensome toil of the past behind.

To take just one example, consider the percentage of the total population employed in agriculture. Often romanticized, farming is, in fact, backbreaking labor. Fortunately, fewer and fewer people are actually doing it. When China first began to open itself up to markets in 1978 (a little more than a generation ago), 70.5 percent of the population worked in agriculture. After four decades of market-driven transformation, that figure in 2015 was 28 percent.29 Unlike in China, no one in the United States has memories of a majority-agricultural workforce. But as recently (in the grand historical scheme of things) as 1870, 46 percent of the population worked on farms. In 1940, well within American cultural memory, 17.3 percent of the population still worked in agriculture. As of 2009, 1.1 percent did.30 Available data worldwide show a similar pattern.31

Technology has lightened the burden of labor more generally as well. In 1950, the average annual number of hours worked per worker was 2,226.47 hours (about a forty-three-hour workweek in a fifty-two-week year). In 2016, it was 1,855.04 (about a thirty-six-hour workweek in a fifty-two-week year).32

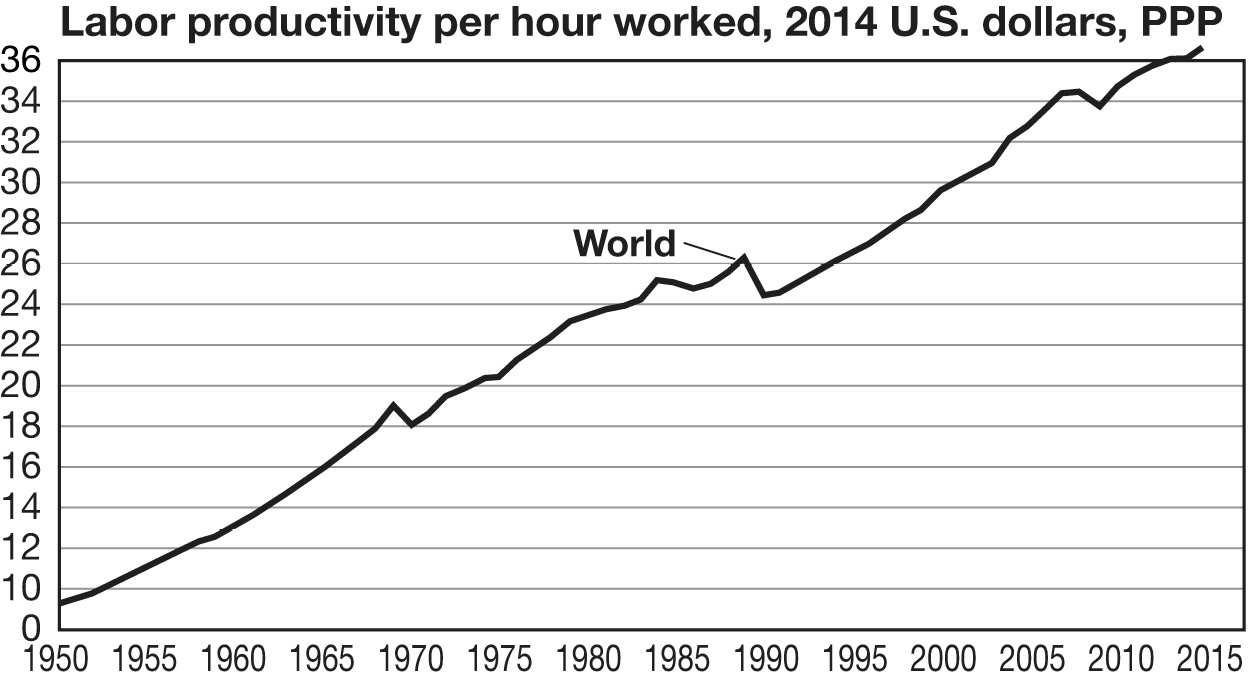

Because of the vast time scope and the many countries involved in discerning such a figure, many of which either stopped existing or only began to exist or report data at some point during the measured period, it is worth taking these figures with at least a grain of salt. But the trend they describe is undeniable. And it is made possible by incredible increases in productivity. Again, available figures have their limitations. But those we do have paint an amazing picture: global labor productivity at $9.30 per hour worked in 1950, and at $36.64 per hour worked in 2015 (measured in 2014 U.S. dollars).33

Simply put: Getting more done in less time means less work. Indeed, the lightening of human toil that capitalism has enabled is so thorough that major public policy debates in developed countries center around getting more people to work—a debate that would have made no sense to any of our ancestors. This is a vital challenge, to be sure. It is increasingly obvious that work—meaningful, valued work—is essential to human happiness. Creating new sources of such work may be one of the most important political and cultural tasks of the next century. But let’s be clear: This is a good problem to have compared to the historical alternatives.

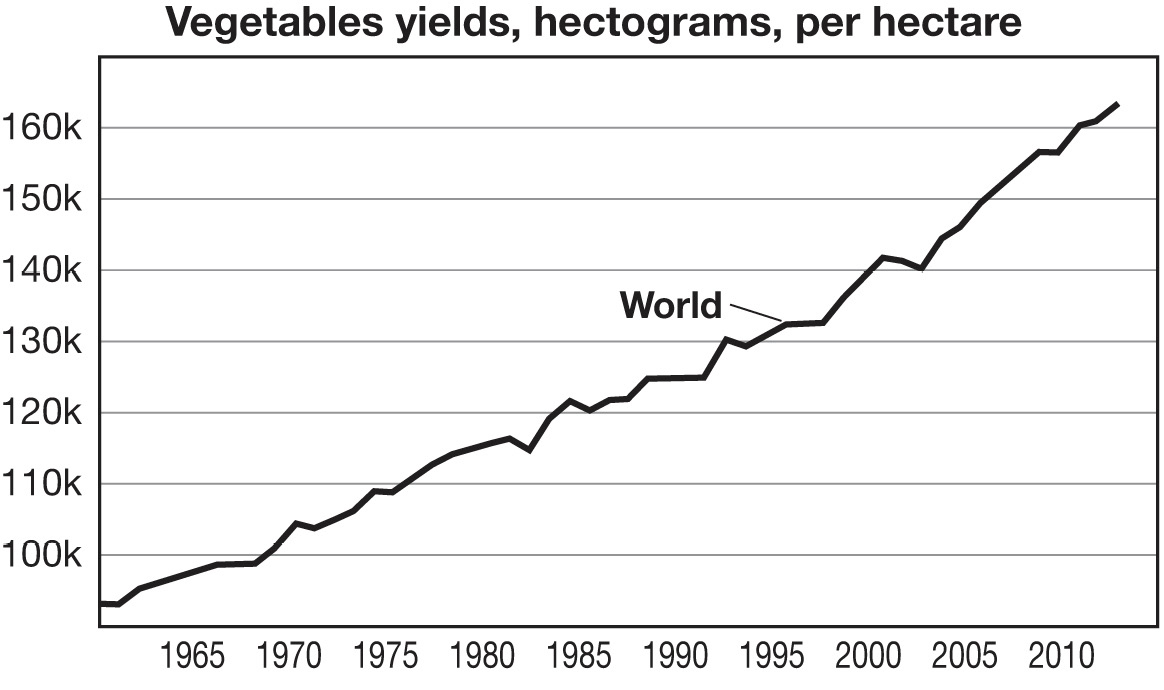

Another way in which capitalism is liberating is that it has allowed humanity to escape the Malthusian trap. Thomas Malthus, writing in the late eighteenth century, believed that the increase in population would always outpace the means of food production. For this, he is mocked today, but in truth his diagnosis was accurate for his time.34 Think again of the farmer, who throughout human history struggled, often in vain, just to keep himself and his family at subsistence level. And compare that to today’s soaring vegetable crop yields:35

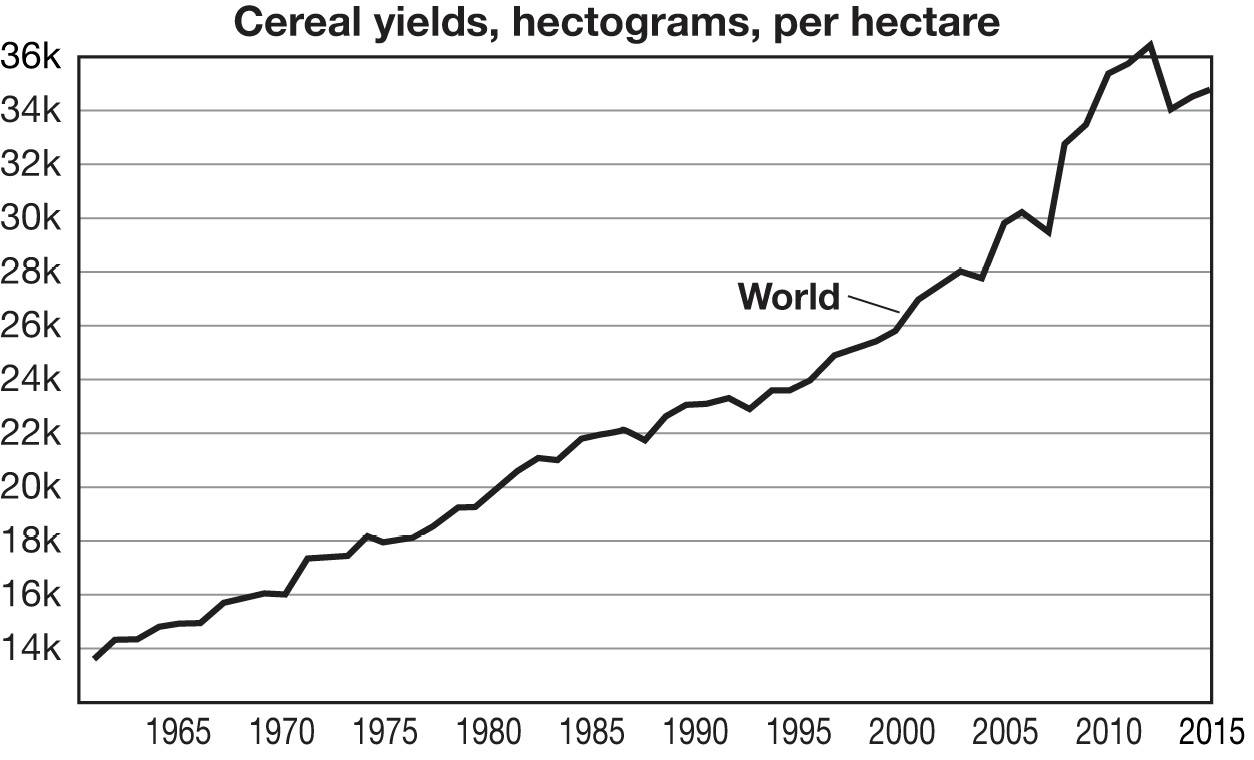

and cereal yields:36

Malthus may have accurately described his time, but capitalism lifted what seemed like an eternal curse of mankind.

Consider the New Testament miracle of the loaves and fishes, in which Jesus fed 5,000 people with a few baskets of bread and fish. The apostle Philip called this crowd so vast that not even more than half a year’s wages could have fed them all.37 Half of the median wage today in America would amount to something like $28,000,38 with which one could purchase multiple satisfying food items for the vast crowd. And this is only one example of the transformative power of capitalism. To keep things biblical, consult a study by Brian Wansink and C. S. Wansink that found that depictions of the Last Supper have grown both tastier and more generous over time, reflecting the increase in food options and portions over the centuries.39 To be more numerate, consider, for example:

• The world produced only 53.6 percent as much food in 1961 as it did on average in 2004-2006, whereas in 2013 it produced 119 percent as much.40

• Meat consumption per person in developing countries has nearly doubled since 1964.41

• The global average food supply per person per day has risen by more than 600 calories since 1961:42

• The overall food consumption shortfall among food-deprived persons has declined precipitously since as recently as 1992.43

• And, most stunning, the worldwide total of undernourished persons has plummeted since 1992, when it approached 1 billion, to now less than 700 million.44

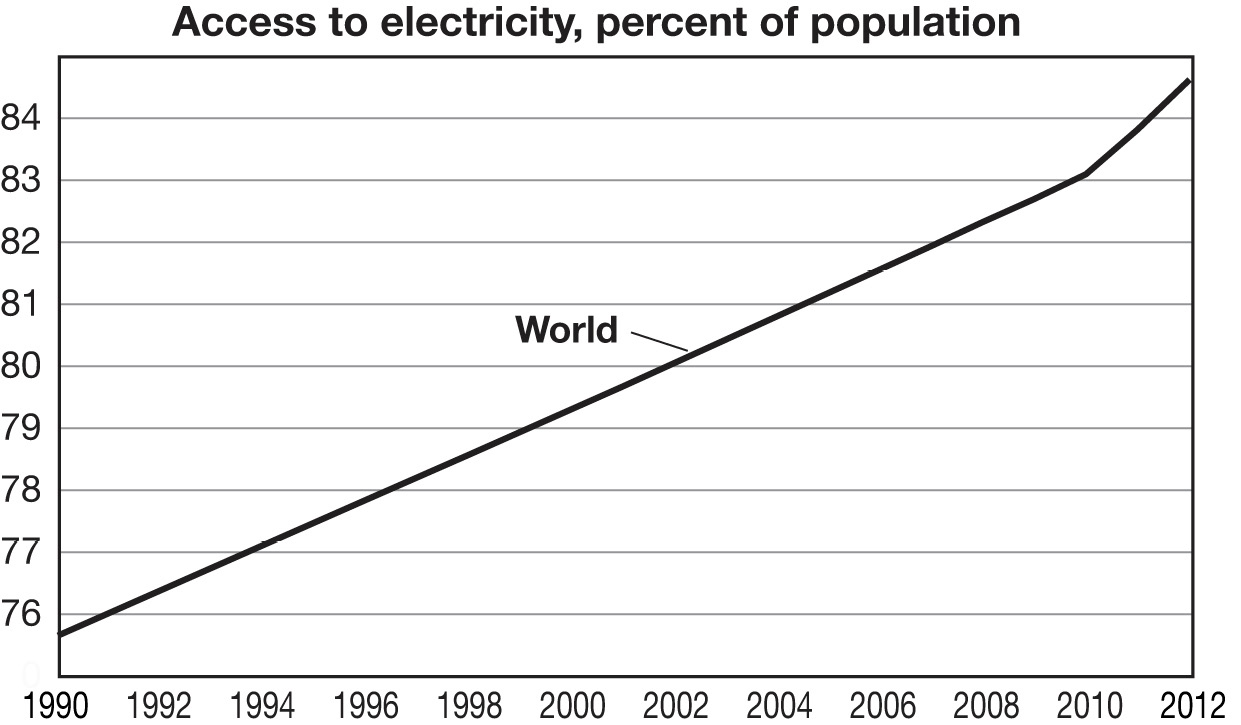

We also have more and cheaper energy than ever before. Worldwide access to electricity—a utility that, let us not forget, simply did not exist for human use for thousands of years before the modern age—has steadily increased, from 75.65 percent in 1990 to 84.58 percent in 2012:45

All are testaments to the modern-day miracle of capitalism.

The skeptical reader may be annoyed that I am crediting all of these things to capitalism. After all, science and technology are not inherently “capitalist.” And that is true. People invented and discovered things long before anything like a capitalist system came online. But, as I have already discussed at length, science and technology were routinely made subservient to politics and religion prior to the Lockean Revolution. Innovation was literally a crime or sin in many parts of the world, because innovation was a threat to the established order. The freedom of the market economy is really the freedom to innovate, to find efficiencies in existing practices, and/or to invent new practices that render the old ways obsolete. People may have been free to build a better mousetrap that may have existed for millennia, but the freedom to bring a better mousetrap to market is a remarkably recent development.

Capitalism is actually the most liberating force in human history. Matt Ridley estimates that, with the average human consuming 2,500 watts per second, it would require 150 humans pedaling on exercise bikes to power the lifestyle to which each person in the world is becoming increasingly accustomed. For Americans, the number is 660 people.46 Economist Mark J. Perry estimated the number of domestic servants the average American would need to replace the technology we all rely on. To maintain the same level of convenience would require the physical output of about 600 people (keep these figures in mind next time you watch Downton Abbey, with its apparent multitude of servants).47 Either way, the proliferation of energy has immensely benefited mankind.

But even if the world were running out of resources (which it is not), we are continuing to do more with less, thanks to the market’s peerless ability to maximize efficiency in ways impossible to central planners. According to a 2013 study by the Alliance to Save Energy, “U.S. economic output expanded more than three times since 1970 while demand for energy grew only 50%,” resulting in millions fewer barrels of oil used than otherwise would have been. University of Manitoba natural scientist Vaclav Smil—Bill Gates’s favorite expert on these issues—identified some areas that drove this efficiency: modern steel production requires only 20 percent of the energy it did in 1900; aluminum production requires 70 percent less energy now than it did then; manufacturing nitrogen fertilizer requires 80 percent less energy now than it did then. Similarly, technologist Ramez Naam calculates that the energy required to heat a house has decreased 50 percent since 1978, and the amount of energy required for water desalination is down 90 percent since 1970.48 The United States now uses half as much energy per unit of GDP as in 1950, and the world uses 1.6 percent less energy for each dollar of GDP growth every year.49 The U.S. also uses no more water today than it did in 1980, despite a population increase of some 80 million.50

This efficiency has appeared in material production as well. Vaclav Smil points out that producing a dollar of value in the United States in 1920 required 10 ounces of material, whereas now it requires only 2.5. And the 11 million cell phones that existed in 1990 weighed 7,000 tons, whereas the 6 billion or so that exist today collectively weigh only one hundred times more.51

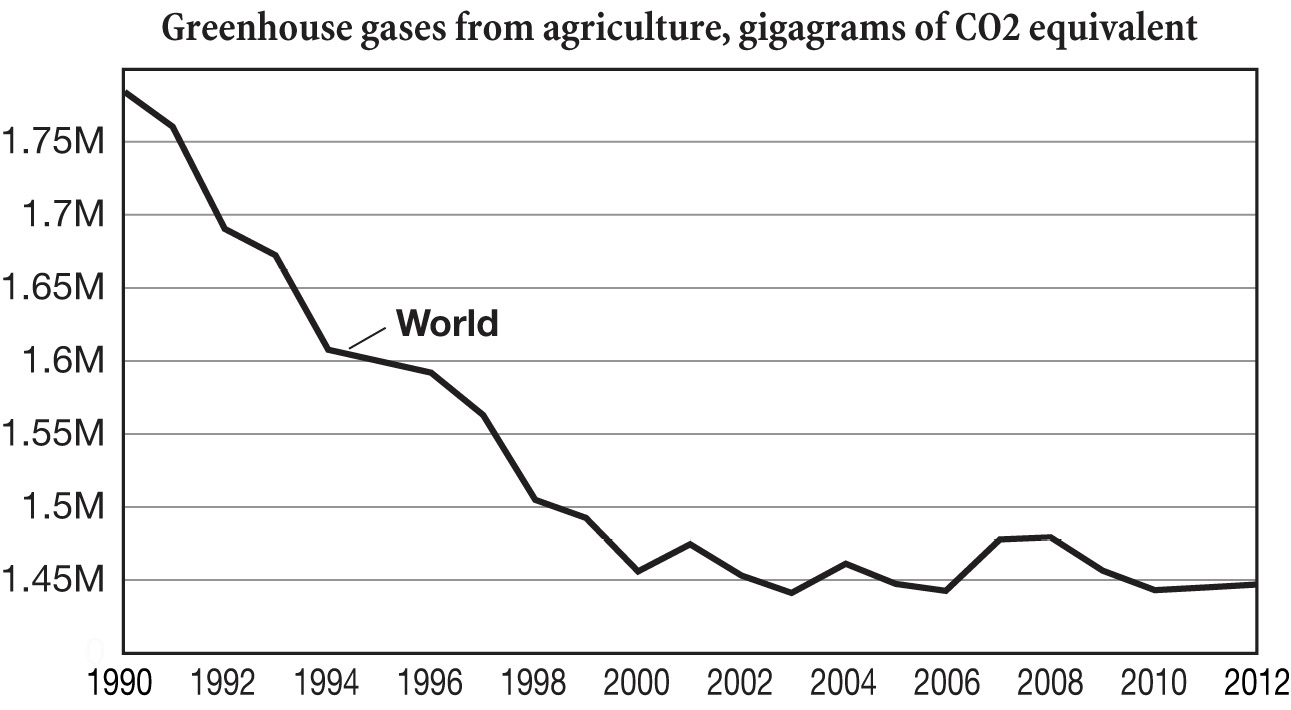

To go back to farming for a moment, we are not simply achieving the massive increase in yields by plowing in more inputs. In fact, we’re doing it with fewer greenhouse emissions.52

Contrary to what you may be hearing, resources are bountiful, and our innovation-driven efficiency in using them wisely is on the rise.

Capitalism has also completely transformed transportation, a depressingly primitive affair from the invention of the wheel to the first passenger train, limited, as it was, by “hoof and sail.”53 Here is historian William Manchester’s account of travel in the Middle Ages:

Travel was slow, expensive, uncomfortable—and perilous. It was slowest for those who rode in coaches, faster for walkers, and fastest for horsemen, who were few because of the need to change and stable steeds. The expense chiefly arose from the countless tolls, the discomfort from a score of irritants. Bridges spanning rivers were shaky (priests recommended that before crossing them travelers commend themselves to God); other streams had to be forded; the roads were deplorable—mostly trails and muddy ruts, impassable, except in summer, by two-wheeled carts—and nights en route had to be spent in Europe’s wretched inns. These were unsanitary places, the beds wedged against one another, blankets crawling with roaches, rats, and fleas; whores plied their trade and then slipped away with a man’s money, and innkeepers seized guests’ baggage on the pretext that they had not paid.54

Manchester also relates some contemporary travel times, in days, from Venice—a commercial center of the medieval world—to various other places: Damascus (80 days), Alexandria (65), Lisbon (46), Constantinople (37), Valladolid (29), London (27), Palermo (22), Nuremberg (20), Brussels (16), Lyons (12), Augsburg (10).55 Columbus’s first voyage took more than two months.56 In 1830, a trip from New York to Chicago took three weeks.57 All of these journeys are now achievable in less than a day. And, thanks to the market, the ability to travel is available to more people every year.58 Just as capitalism has gone a long way toward liberating us from darkness and toil, it has also toppled the tyranny of distance.

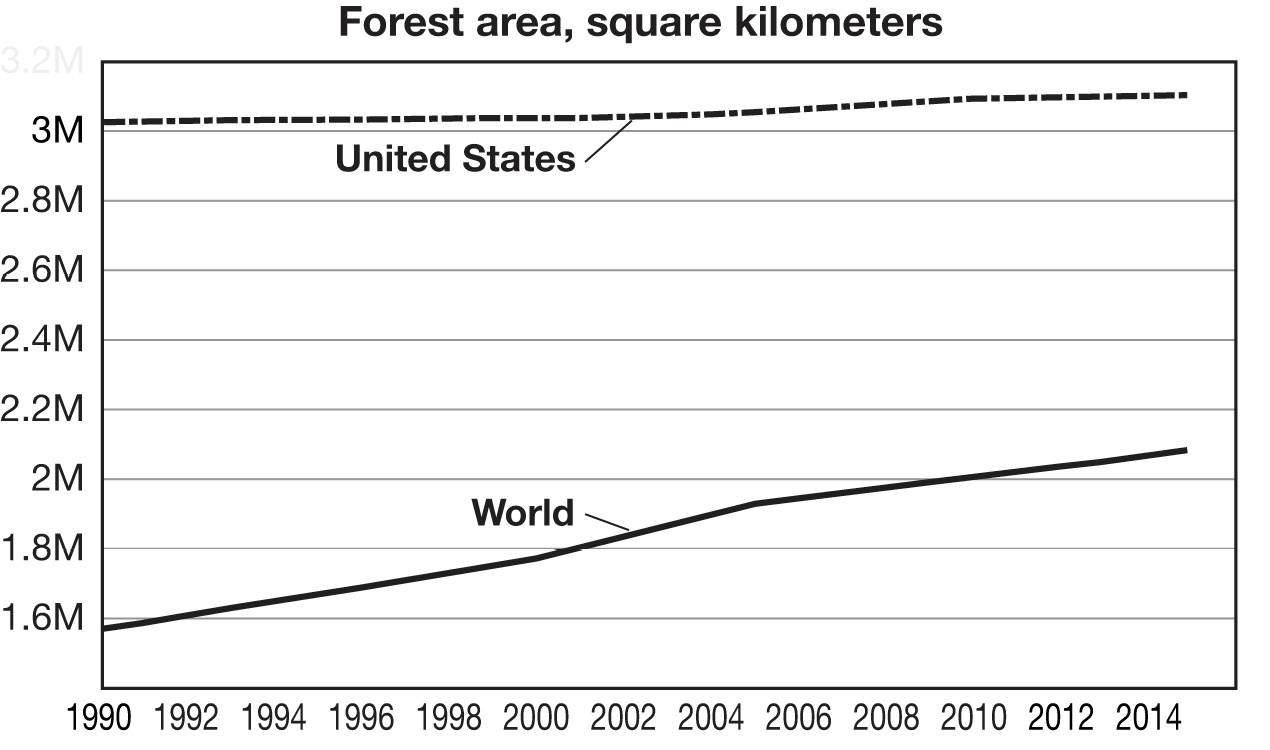

While it’s certainly true that capitalism and economic growth have come at a cost to the environment, free-market societies are far better stewards of the environment than command economies. Moreover, capitalism provides the means to remedy the damage.

Forests in wealthy countries have been expanding for decades.59 Despite widespread forecasts to the contrary, Europe’s forests grew during the 1980s and 1990s.60 From 1960 to 2000, India’s forests grew by 15 million hectares (larger than the state of Iowa). Leaving out the heavily developing nations of Brazil and Indonesia, global forests have grown by roughly 2 percent since 1990.61 And forest area has grown in the United States and China, the world’s two wealthiest countries.62

Innovation allows us to replace diminishing or depleted resources with better ones. Ronald Bailey notes that “railroads, the 19th century’s ‘modern’ form of transportation, consumed nearly 25 percent of all the wood used in America, for both track ties and fuel.”63 Today, however, we no longer use wood for fuel, and we use it much less as a construction material (and paper usage is plummeting thanks to the digital revolution).

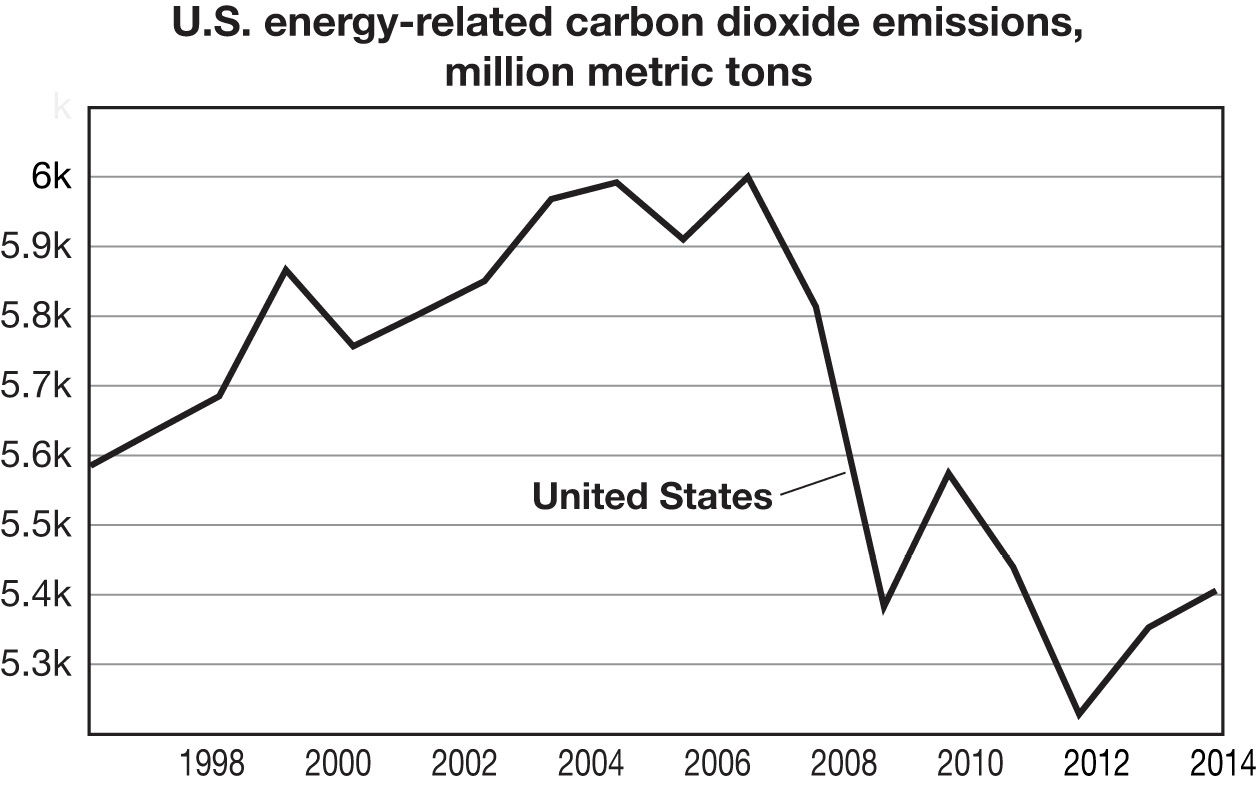

Similarly, when we decide that the by-products of industry are becoming a problem, the market allows us to innovate techniques that fix the problem. Hence, recently, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. have been on a downward trend, not upward:64

Because we are doing more with less, and because capitalism’s wealth allows us to spare what once we might have heedlessly plundered from the earth, capitalism is ultimately good for the environment. “Pollution levels are falling in rich countries and will begin to drop in poor countries as they become wealthier,” writes Bailey.65

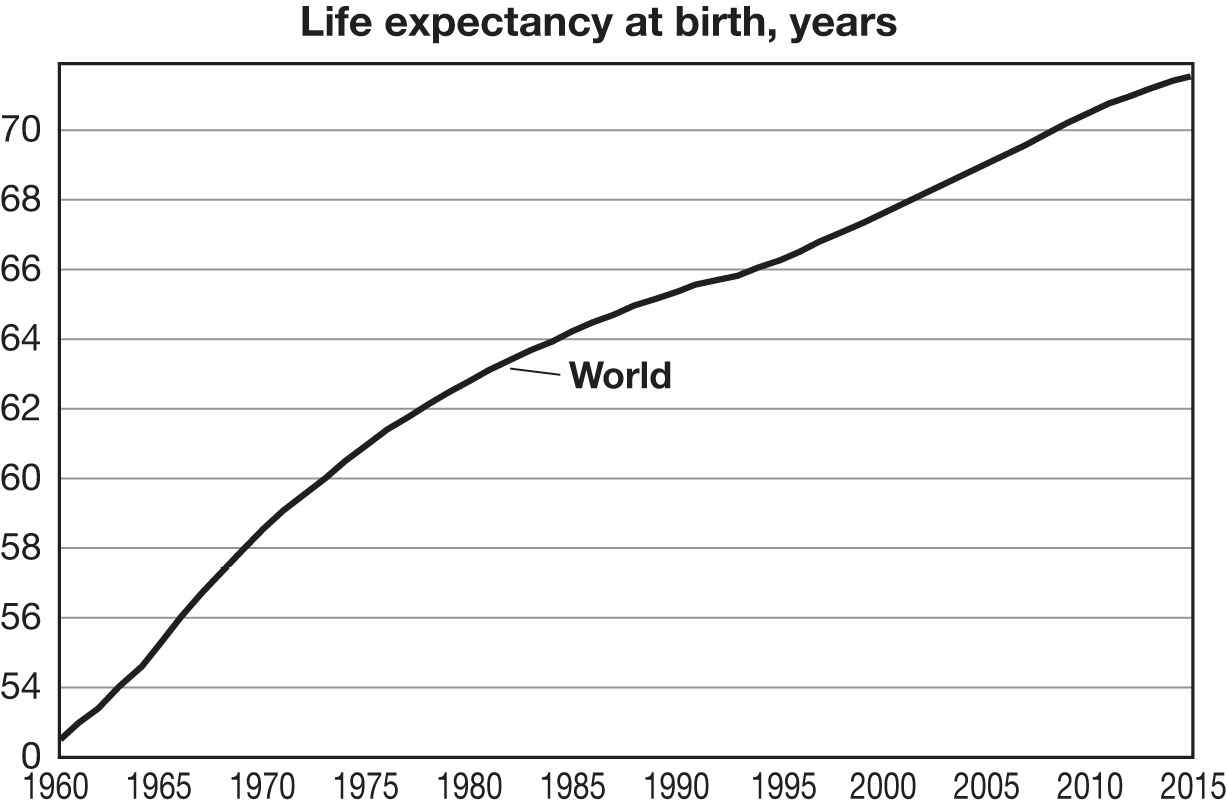

Capitalism has also made us healthier. It has, for example, led to longer lives for more people. For premodern societies as a whole, life expectancy was under forty years.66 The shades (souls) of ancient Greeks often met Hades by age eighteen; most Roman shades met Pluto by twenty-two. A 2002 study of pre-Columbian Native American skeletons found that few people lived past fifty, or even past thirty-five.67 Not many Europeans in the Middle Ages reached middle age; half were dead before their thirtieth birthday. A young girl could expect to live to twenty-four. Men fortunate enough to survive past their thirties or early forties could reasonably expect to live a bit longer but would outwardly resemble senior citizens by what we still consider middle age.68

We’re a lot better off than that today. Even the global average life expectancy at birth in 1960, at 52.48 years, would have compared favorably to anything from the past. But in 2015 that same figure was 71.6 years.69

Today, the average person born worldwide can expect to live decades longer than anyone in the past could have reasonably hoped for. Capitalism literally gives the average person “new life” in the sense that old age was, for the average person, an unrealistic ambition. Technology cannot create more time, but it can give us the opportunity to have more of it.

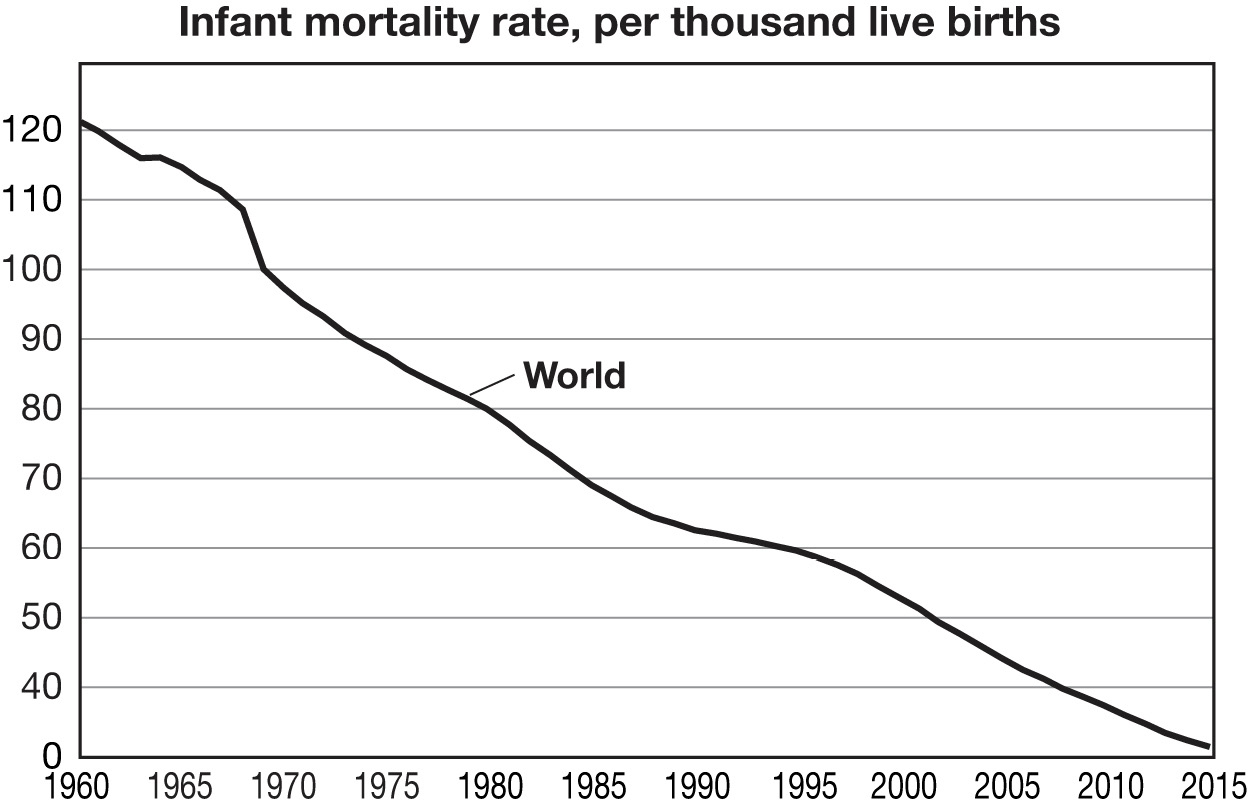

But capitalism gives new life in another way: We are simply more likely to live in the first place.70 In premodern societies, almost one-third of children died before age five. Infant mortality in hunter-gatherer societies was almost thirty times greater than in America today, and child mortality was more than one hundred times greater. The average worldwide population-weighted child mortality rate was 43 percent in 1800. The worst-off countries in 1800 suffered the death of half of all children, but even the best-off countries endured the passing of about a third of all children. In America, as recently as 1890, infant mortality was 22 percent of new births.71

Today, the worldwide, population-weighted child mortality rate is 3.4 percent. Child mortality is 1.3 percent in China, which, along with Brazil, has experienced a fourfold decrease of child mortality over the past four decades.72 Since 1960 the worldwide infant mortality rate has declined from 121.9 per 1,000 live births to 31.7:73

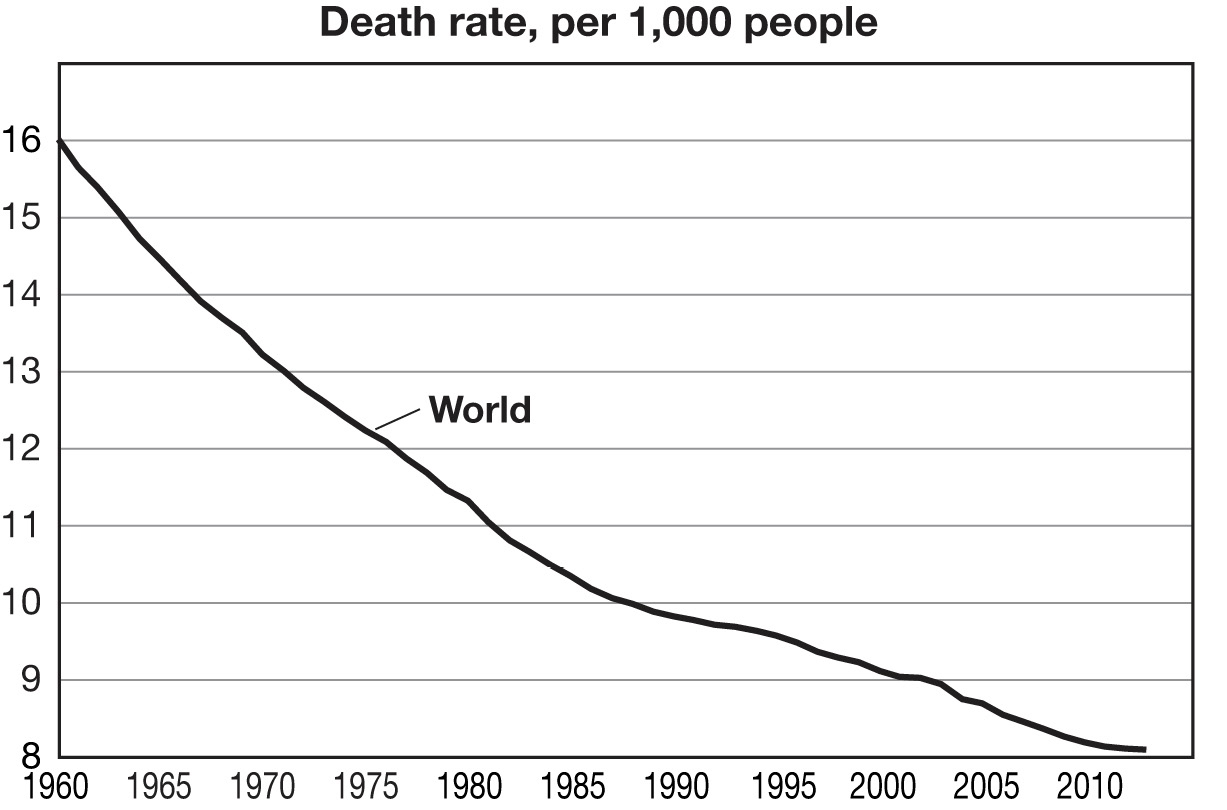

Similarly, the mortality rate worldwide for all ages has decreased from 16.03 per 1,000 people in 1960 to 8.09 per 1,000 people in 2013.74

Think of all the value created because people simply lived.

This has been happening in part simply due to the correlation between health and wealth.75 More specifically, it’s from better medical care. Consider just a few aspects of medical care in the past. Would you like to be treated by the medieval doctors described by William Manchester?

The stars were known to be guided by angels, and physicians were constantly consulting astrologers and theologians. Doctors diagnosing illnesses were influenced by the constellation under which the patient had been born or taken sick; thus the eminent surgeon Guy de Chauliac wrote: “If anyone is wounded in the neck when the moon is at Taurus, the affliction will be dangerous.” Thousands of pitiful people disfigured by swollen lymph nodes in their necks mobbed the kings of England and France, believing that their scrofula could be cured by the touch of a royal hand. One document from the period is a calendar, published at Mainz, which designates the best astrological times for bloodletting. Epidemics were attributed to unfortunate configurations of the stars…76

Would you entrust your teeth to “dentists” in medieval England, who relied on “herbal remedies, charms, and amulets” for both cleaning and removal?77 Would you like to have a limb amputated before the first painless surgery with anesthetic in 1846?78 Would you trust medical examinations before 1896, when blood pressure instruments and X-ray machines—the latter costing only 20 percent in 2012 of what they cost in 191079—were invented? Or before 1901, before electrocardiograms, which weren’t even used widely until the 1920s?80 Or would you even like to be alive in America in the 1920s, when, according to Lewis Thomas, former dean of the Yale and New York University Schools of Medicine, going to a doctor probably lowered your chances for survival and most mothers by necessity became domestic nurses?81 Or around the same time, when sepsis infection killed nearly half of major-surgery patients?82 Even as recently as 1990, the number of women dying in or from childbirth worldwide was far higher than today.83 And as recently as a decade ago, sequencing a genome cost millions of dollars versus $10,000 today.84 The steady advance of medical care has gone a long way toward improving overall health outcomes.

Perhaps the most prominent result of these and other advances has been the steady reduction of death from disease. Pharaoh Rameses V could not with all his power prevent his own death from smallpox. (In fairness, there’s no cure for smallpox today, either, but there is a vaccine that works as a cure up to four days after infection.) Nathan Rothschild, the richest man in the world in 1836, died that same year from what today is an easily treatable infection.85 While Calvin Coolidge was president of the United States in 1924, his son died within a week from infection of a blister he got playing on the White House lawn.86 And, again, these were some of the wealthiest, most powerful people in the world. Life was much worse for most;87 malaria, typhoid fever, and dysentery killed thousands annually.88

Today, however, a wide variety of diseases—mumps, rubella, malaria, measles, sleeping sickness, elephantiasis, and river blindness—are drastically retreating worldwide, suggesting that “the total eradication of many diseases is now a realistic prospect.”89 In America, the death rate from infectious disease was only 2 percent in 2009.90 Other disease indicators have also significantly improved. Malaria, typhoid fever, and dysentery are non-factors in the developed world,91 with the last in particular probably being better known as a video game meme (“You have died of dysentery”) than a deadly disease.92 Seventy-five percent fewer people died from strokes in 2013 than did in the 1960s.93 AIDs peaked in the late 1990s; by 2010 incidence had decreased 20 percent from 1997.94 Cancer is still a terrible scourge, but we’re dealing with it better than ever. Apart from lung cancer, cancer incidence and death rate fell 16 percent from 1950 to 1997 and accelerated thereafter; once smoking decreased, lung cancer began to fall as well.95 As the number of artificial chemicals has dramatically increased over the past four decades, overall cancer death rates and age-adjusted cancer incidence have both declined. Half of all cancer patients died within five years of their diagnosis in the 1970s; 68 percent now live past that. Overall cancer incidence has declined 0.6 percent annually since 1994, saving 100,000 people today who otherwise would have died from the disease. The death rate from leukemia is 7.1 per 100,000, half of what environmental alarmist Rachel Carson fretted over in Silent Spring. An estimated 10,450 children were diagnosed with cancer in 2014, less than 1 percent of overall cancer deaths, and 80 percent of those diagnosed survive five years or more, up from 50 percent in the 1970s.96

Cancer causes 186 of every 100,000 deaths annually, but that’s in large part because far more Americans live past the age of sixty-five, the median age of cancer diagnosis. Americans in the early twentieth century did not live long enough to develop 75 percent of today’s cancers.97 Non-disease-based indicators have improved as well: Disability rates in Americans over sixty-five decreased from 26.2 percent to 19.7 percent between 1982 and 1999 (twice as fast as the mortality rate decreased).98 Historically, if you managed to make it to old age, it was unlikely you could be productive, never mind prosperous. Today, senior citizens in developed countries are a mass class of people.

We’re also more literate and more educated than ever before. For most of human history, most people—and more women than men—were illiterate. The great stories, such as the Iliad, Odyssey, and Beowulf, were told orally long before they were ever written down. Education of any kind was a privilege of the elite. As recently as 1820, only 12 percent of the world’s population was literate. The wealth created by capitalism has changed all of this. By 2014, only 15 percent of the world’s population remained illiterate—almost a complete inversion in less than two hundred years.99

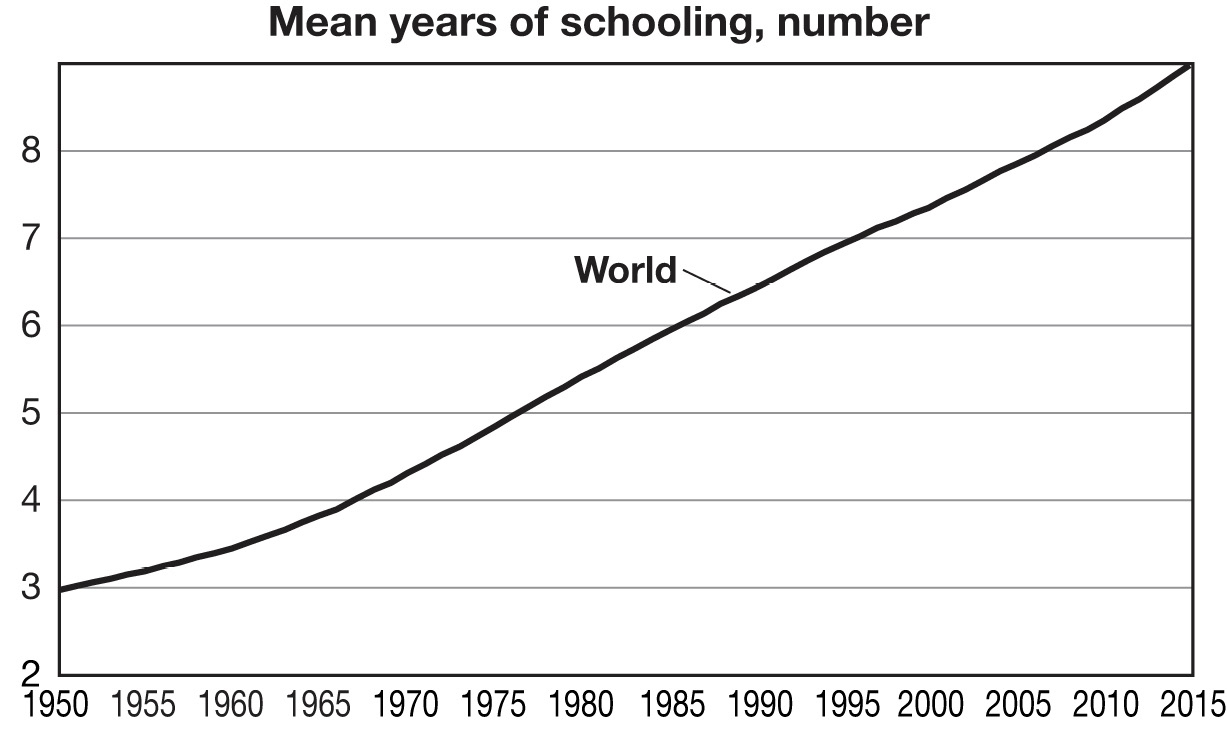

Education has also increased. The average amount of years of education worldwide has increased from 2.97 years in 1950 to 8.99 in 2015:100

Thanks to capitalism, education and literacy are no longer the privilege of the elite but increasingly common to all.*

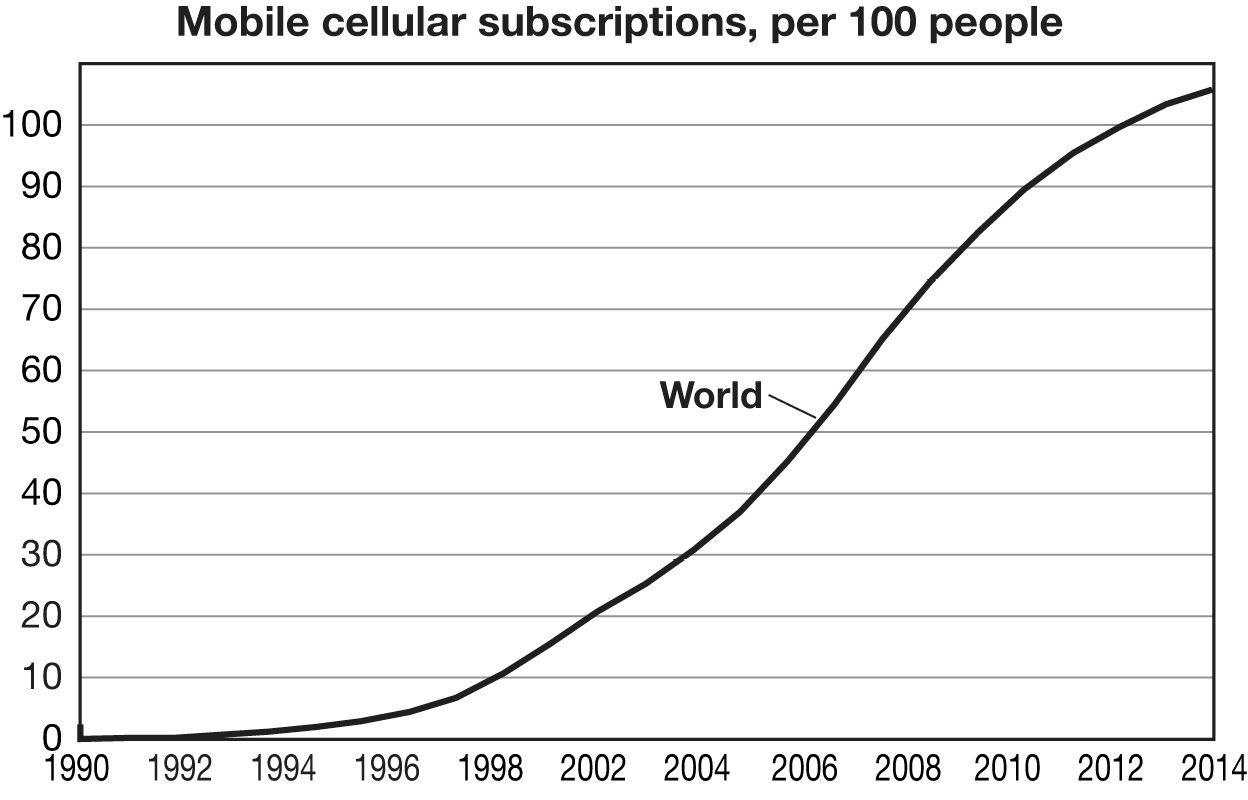

Capitalism has also completely transformed communication. For the entirety of human history until about 170 years ago, the travel speed of news was limited to the travel speed of people: i.e., by “foot, horse, sail, or, more recently, rail,” as economist Robert J. Gordon points out.101 History records many darkly comic examples of this defect in communication. Thus did the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War, at first having decided to destroy the rebellious Mytileneans, send one boat to do just that. Changing their minds the next day, their only recourse was to send another boat after the first, with instructions to row as fast as it could to arrive in time to dissuade the first boat.102 The Battle of New Orleans, technically the final skirmish of the War of 1812, occurred after the War of 1812 had actually ended.103 The first telegram, sent in 1844, inaugurated a new era in human communication.104 But as impressive as its early innovations must have been to those who experienced them, they seem laughably primitive to us today because of the pace of technological advance. And the technology continues to evolve: In 2010, each American household had nearly 2.6 cell phones; in 2013, 91 percent of American adults had a cell phone.105 Mobile cell phone subscriptions have increased from 0.27 per 100 people in 1990 (think Gordon Gekko and his brick phone in 1987’s Wall Street) to 105.74 per 100 people(!) in 2014.106

The calls made on these devices, moreover, are cheaper. We take for granted today that a fixed-price phone service covers most essentially instantaneous long-distance calls, yet as recently as seventy years ago such a call would require multiple operators and could cost an hour’s wages.107 We even have technology—Facebook, Twitter, Skype—that allows free, instantaneous communication without a phone. For the first time in human history, two people can call one another without even knowing where the other is.108 That is a testament to the incredible transformative power of capitalism.

Markets have also utterly transformed computing. Iron Sky, an absurd science fiction film, illustrates this point. In this 2012 film, a Nazi cadre secretly escaped to the dark side of the moon at the end of World War II and spent the intervening years plotting an invasion of Earth. Their plans receive a considerable boost when they steal an American astronaut’s smartphone, which alone has more computing power than the totality of their equipment up to that point.109 Sound far-fetched? Well, yes. But the computing power differential is highly plausible. ENIAC, one of the first “modern” computers, debuted in 1946, right around the time the Nazis flee to the moon in Iron Sky. It weighed 27 tons, required 240 square feet (22.3 square meters) of floor space, and needed 174,000 watts (174 kilowatts) of power, enough to (allegedly) dim all the lights in Philadelphia when turned on.110 In 1949, Popular Mechanics predicted that one day a computer might weigh less than 1.5 tons.111 In the early 1970s, Seymour Cray, known as the “father of the supercomputer,” revolutionized the computer industry. His Cray-1 system supercomputer shocked the industry with a world-record speed of 160 million floating-point operations per second, an 8-megabyte main memory, no wires longer than four feet, and its ability to fit into a small room. The Los Alamos National Laboratory purchased it in 1976 for $8.8 million, or $36.9 million in today’s inflation-adjusted dollars. But as predicted by Moore’s Law (the number of transistors that can fit on a microchip will double roughly every twenty-four months),112 modern computing has improved and spread beyond even the wildest speculations of people living at the time of any of these computers (certain science fiction excepted). A team of University of Pennsylvania students in 1996 put ENIAC’s capabilities onto a single 64-square-millimeter microchip that required 0.5 watts, making it about 1/350,000th the size of the original ENIAC.113 And that was twenty years ago.

Popular Mechanics’ prediction proved correct, though a bit of an (understandable) understatement. Still, try telling its 1949 editorial staff that today we hold computers in our hands, place them in our pockets, and rest them on our laps. Laptop computers with 750 times the memory, 1,000 times the calculating power, and essentially an infinitely greater amount of general capabilities as the Cray-1 are now available at Walmart for less than $500.114 Bearing out the Iron Sky comparison, a smartphone with 16 gigabytes of memory has 250,000 times the capacity of the Apollo 11 guidance computer that enabled the first moon landing.115 A life’s wages in 1975 could have bought you the computing power of a pocket calculator in 2000.116 In 1997, $450 could have bought you 5 gigabytes of hard-drive storage that is free today.117 A MacBook Pro with 8 gigabytes of RAM has 1.6 million times more RAM than MANIAC, a 1951 “supercomputer.”118 Forget angels on the head of a pin: Intel can fit more than six million transistors onto the period at the end of this sentence.119

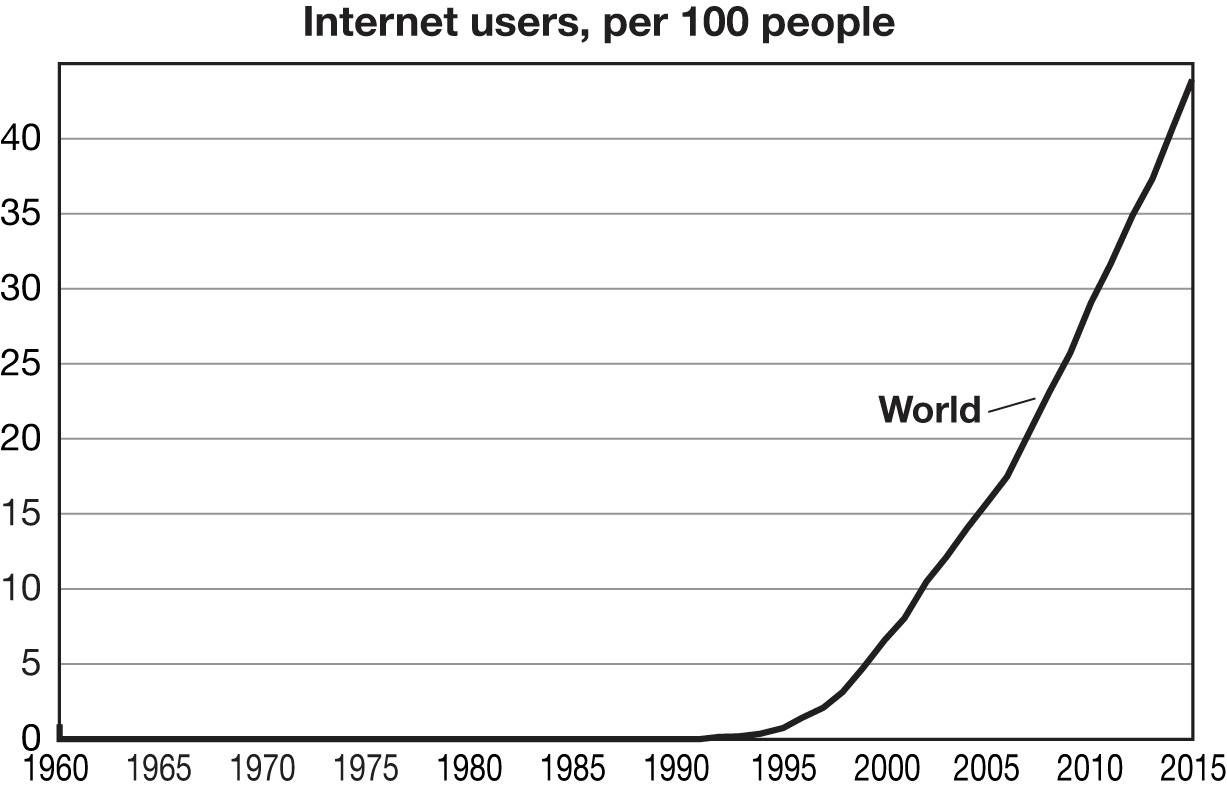

What this all means for the consumer is an unprecedented spread of technology. Today’s cell phones exceed the computing power of machines that required rooms mere decades ago. Nearly half the world uses the Internet, up from essentially zero in 1990.120

Today, then, computers are better, faster, smarter, more prevalent, and more connective than ever before. In the 1990s, progressive policy makers fretted over something called “the digital divide.” They convinced themselves that, absent government intervention, the Internet would be a plaything for the wealthy. They raised new taxes, transferred wealth, paid off some constituents, and claimed victory. But the truth is that the Internet was always going to be for everyone, because that is what the market does. It introduces luxuries for the wealthy, and the wealthy subsidize innovations that turn luxuries—cell phones, cars, medicine, computers, nutritious food, comfortable homes, etc.—into necessities. It is the greatest triumph of alchemy in all of human experience, and the response from many in every generation is ingratitude and entitlement.

Now, none of this is to say that this miraculous explosion in material prosperity has not come with costs. Such is the nature of this life. Everything has trade-offs.

Nor is it to say that government hasn’t played a role in evening out some of the excesses of human enrichment. But paternalistic government is as old as the first Big Man leading the first band of hairless apes running across the savannas of Africa. Paternalism is the logic behind the rule of every Caesar, king, pasha, sultan, commissar, and emperor. Paternalism did not create the Miracle. Human ingenuity unleashed by the miracle of liberty, chiefly economic liberty—which yields political liberty—made this possible.

And yet, in the modern era, every generation takes the Miracle for granted. We are told, by people who should know better, that capitalism is making us sicker, poorer, and more exploited. That we are falling farther behind and therefore must look even farther behind us to some mythological golden age when we had it better. One typical poll result revealed that 66 percent of Americans believe that extreme poverty has “almost doubled in the past 20 years, 29 percent think it has not changed, whereas only 5 percent correctly stated that it has halved.” The numbers are no better elsewhere in the developed world: 58 percent of Britons assumed extreme poverty had increased and a third thought it had stayed the same.121 These pessimists answer in vain Thomas Babington Macaulay’s inquiry: “On what principle is it, that when we see nothing but improvement behind us, are we to expect nothing but deterioration before us?”122

The free-market system depends on values, ideas, and institutions outside of the realm of economics to function, a topic I covered in the second half of this book. But for now the important point is this: The free-market system is not merely the best anti-poverty program ever conceived; it is quite literally the only anti-poverty system ever invented. Poverty is the natural human condition, and it remained the steady state of human affairs for nearly all of human history. Socialism as a label is a relatively recent invention. But socialism as an idea is beyond ancient. Socialism is the economics of the tribe. We evolved as a cooperative, resource-sharing species. This is one reason why the idea of socialism keeps coming back. It’s in our brains, alongside myriad other factory-preset ideas and desires: that capitalism is unnatural; individual liberty and free speech are unnatural; liberal democratic capitalism is at war with human nature in every generation.

It is a common theme in literature: Every wish comes with a catch. From Goethe’s and Marlowe’s Faust, to Kipling’s “Sing-Song of Old Man Kangaroo,” to Hans Christian Andersen’s “Galoshes of Fortune,” to a half dozen episodes of The Twilight Zone, we must be careful what we wish for. The Miracle of now is the answer to a thousand generations of wishes by people whose lives were poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Capitalism is the greatest peaceful cooperative endeavor for human enrichment ever created—by orders of magnitude. The catch? It doesn’t feel like it. It doesn’t feel cooperative. It doesn’t even feel peaceful. It is full of uncertainty and tumult.

Capitalism cannot provide meaning, spirituality, or a sense of belonging. Those things are upstream of capitalism. And that’s okay. Capitalism is an economic system that is fantastic at doing what we claim we want from economic systems: growth and prosperity. The problem is that what we say we want from an economic system and what we actually want are often different things. Economics is a sphere of the larger civilization, and we want more than what mere capitalism can provide. We want meaning. We want to feel like we’re part of the tribe. But just as a hammer makes for a terrible knife, capitalism is a tool ill-suited for filling the holes in our souls.

Meaning comes from family, friends, faith, community, and countless little platoons of civil society. When those institutions fail, capitalism alone cannot restore them. As a result, human nature starts making demands of the political and economic systems that neither can possibly fulfill. Liberty, economic and political, is recast as the source of our problems. Having lost faith in other realms, we lose faith in the Miracle itself, and we cast about for what feels more natural: tribalism, nationalism, or socialism in one guise or another.

Most people recognize that “consumer confidence” is important for the economy. When people feel optimistic about their own financial situation and the prospects for the overall economy, they are more likely to spend money and businesses invest more in workers and equipment. Tragically, we spend vastly more time talking about consumer confidence than we do about civilizational confidence, and yet civilizational confidence is vastly more important. Western civilization created the Miracle, even if it did so by accident. When we lose our confidence—and pride—in what it has accomplished, we are committing a suicidal act on a civilizational scale.