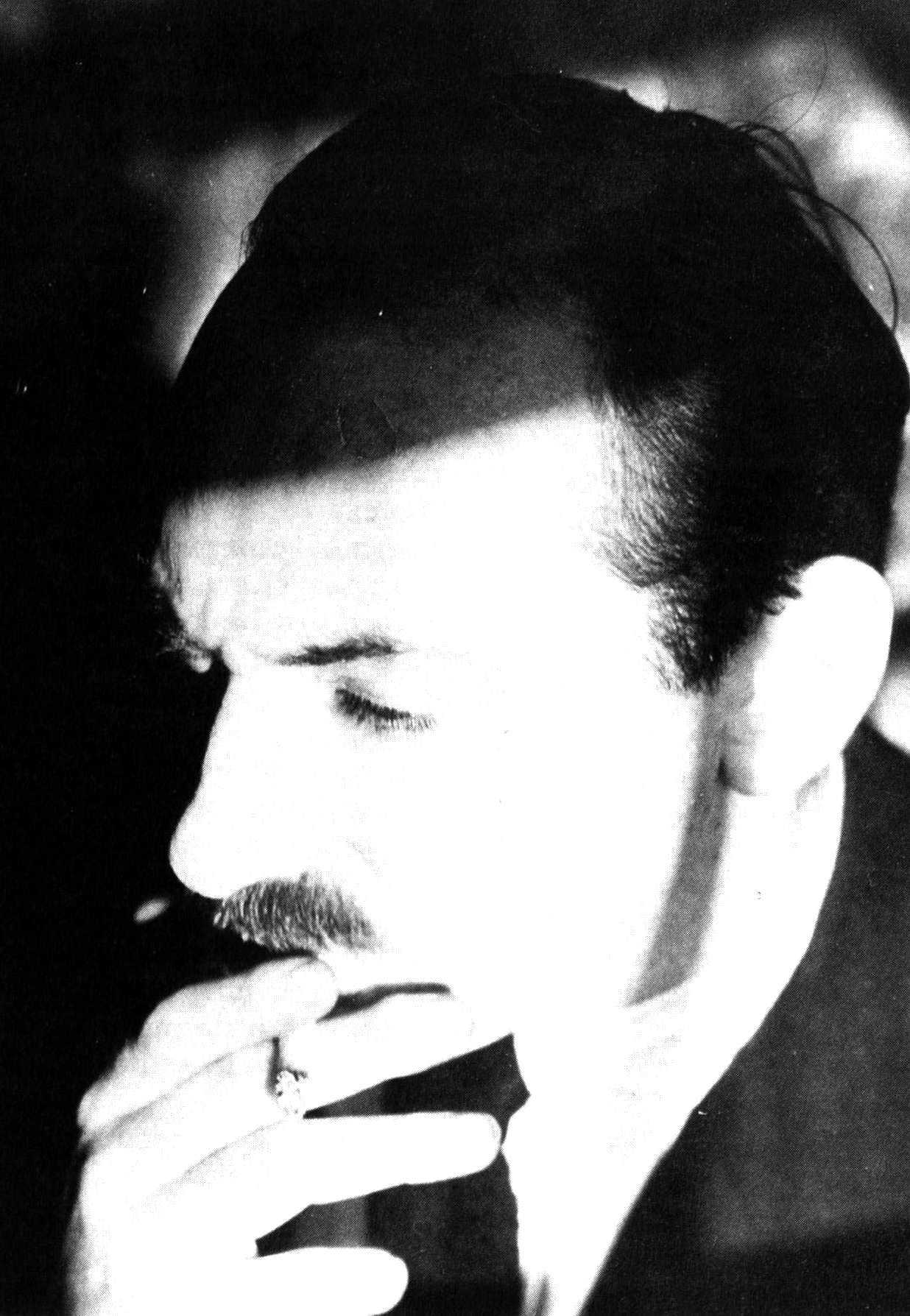

Nathanael West. Courtesy New Directions Publishing Corporation.

IN HIS COLLECTION OF epigrams The Secret Heart of the Clock, Elias Canetti wrote: “At the edge of the abyss, we cling to pencils.” In Nathanael West’s version, we jump. And we laugh as we fall—a scalding, mocking laughter, the abyssal laughter of we-have-nothing-left-to-lose. Not a typical satirist (from the Latin, saturus, literally “filled or charged with a variety of things”), West belongs to what we might term the Heroic-Caustic branch of the literary pantheon. To wit: nothing in his books is built or upheld, nothing grieved over; all is a falling-away, and the emotional tone of the writing is one of spectacular, remorseless negation. As West himself said, “Not only is there nothing to root for in my work … but what is worse, no rooters.” Published in the reformist-minded 1930s, West’s novels presented an evil-twin alternative portrait of the America seen in the “proletarian” novels of coevals Steinbeck, Sinclair, Farrell and Dos Passos. In his books you will find no set pieces on the hygiene of slaughterhouses, nor warmly written passages on the brotherhood of hobos; no soaring hymns to the industrial might of America or “picturesque” depictions of the marginal and alienated. West’s America is brittle, deeply violent, depthless, loud, scarifyingly unfair and as bright as a new toy. This America traffics happily in images of bucolic splendor while grinding people to bits in the urban clockworks. It drapes patriotic banners over its most murderous acts and tactfully draws the screen of “democracy” around its own proximity to mob rule. It proposes as a final reward for long service the state (in both senses) of “California,” which turns out to be a jail of boredom, crammed with latent violence and guarded by palm trees. Not unsurprisingly, in this province of disappointed expectations, there is one delusion that stands out above the rest: romantic love. Love, in West’s books, even more than religion, civic zeal or national pride, constitutes the biggest, most ludicrous, most necessary sham of all, and he lays bare its grandeurs like a med student pithing a dog.

As novelist, he is intriguingly elusive, a shape-shifter, a protean wearer of authorial hats. Each of his books employs a new narrative template. His first novel, The Dream Life of Balso Snell, is a mediocre pottage of juvenile bathroom jokes leavened with highbrow allegorical references. His second book, Miss Lonelyhearts, is an astonishingly achieved novel, bearing as little resemblance to its antecedent as Leaves of Grass did to the wretched Whitmanian doggerel that preceded it. A Cool Million, his third, is a waste of his gifts, though it has a following among his contemporary devotees, and his fourth, The Day of the Locust, is shot through with brilliantly imagined scenes, which never entirely quite hang together as an ensemble.

A useful way to understand a body of work this variegated is through the Kafka paradigm. The Kafka paradigm suggests that the less obviously connected a Jewish writer is to Jewish themes or issues, the more deeply Jewish his writing is at bottom. Like many self-hating Jewish writers, West (born Weinstein) renounced all claims to the religion of his birth and seemed, for that, the more crucially, exactly Jewish. His apocalyptic, deadpan humor and ironic self-detachment, his Testamentary ferocity and his sense of writing as hurtling forward along a chain of collapsing expectations stamp him as an essential member of the ingathering of Isaac Babel, Harold Brodkey and Philip Roth—though he occupies a darker, more lexically fraught corner of it than they do. West was the writer Walter Benjamin would have been if he’d grown up and learned to hunt and fish in America.

The lone book out of all his work which represents the perfect fusion of his artistic means and his creative will is Miss Lonelyhearts. A fiery dance of literary binaries—academic and vernacular, tender and violent, sacred and profane, comic and pathetic—the novel is recounted in the spooling frames of a comic strip and moves with the inner logic of a fever dream. It tells of a few weeks in the life of a desolate advice columnist to the lovelorn who is detached from his faith, his girl, his job and finally his life in a kind of forced march to the verge of nonbeing. The beauty and the originality of the book reside in its supersaturated prose and the architectonics of its spaces. It is built like a Bach fugue or a soaring tensegrity structure, with each sentence sharing equal load-bearing weight and a feeling of seamlessly phased recurrence of parts-of-the-whole. Harold Bloom, with good reason, calls the novel “the perfected instance of a negative vision in American prose fiction.”

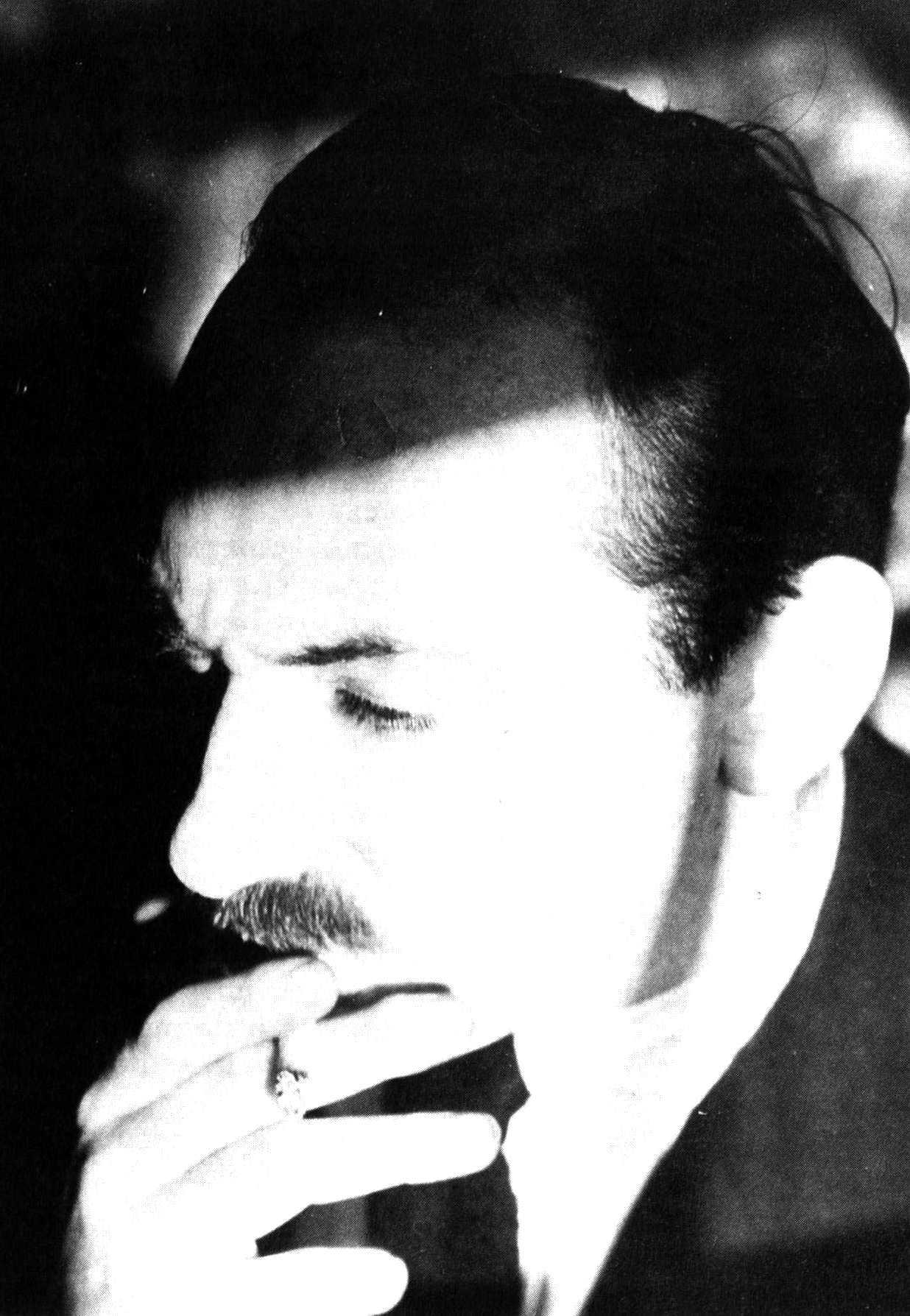

Nathanael West. Courtesy New Directions Publishing Corporation.

Brandishing his artistic credo (“A novelist can afford to be anything but dull”), West wrote Miss Lonelyhearts at the Flaubertian rate of a hundred words a day, each of them sounded out loud in the country air of a cabin in upstate New York. The result, aside from the drastic compression of the language, was a panoply of specialized effects similar to those of Expressionist film, in which a spotlight picks out a telling detail on an otherwise dark stage: lock or keyring. Arising out of the dense weave of the prose, these moments employ percussive metaphors to make West’s larger point: that man is continually in danger of becoming a thing. The sky looks “as if it had been rubbed with a soiled eraser.” A woman’s arms are “round and smooth, like wood that has been turned by the sea.” Miss Lonelyhearts’ tongue is “a fat thumb,” his heart is “a congealed lump of icy fat.” A colleague at his paper has cheeks “like twin rolls of smooth pink toilet paper.”

The only place where the seething, corrosive irony of the prose surface lets up is in West’s descriptions of the natural world. An avid outdoorsman, West in later years kept a brace of bloodhounds as pets, the better to hunt with, and his caressing, sensual, yet oddly Cubist descriptions of plants and landscapes are clearly the product of affectionate observation: “There was no wind to disturb the pull of the earth. The new green leaves hung straight down and shone in the hot sun like an army of little metal shields. Somewhere in the woods a thrush was singing. Its sound was like that of a flute choked with saliva.”

When Miss Lonelyhearts is dragged away to the country by his girlfriend, he has to admit, “even to himself, that the pale new leaves, shaped and colored like candle flames, were beautiful, and that the air smelt clean and alive.”

It was part of West’s genius in Miss Lonelyhearts to stretch a fine skin of caricature over the point-by-point presentation of his story and at the same time tune his ear for dialogue and emotional nuance to such a pitch as to produce real felt inhabited interaction between the characters. The sheerness of this interface, the slipperiness of this linkage, as it slides often within individual sentences from satire to laceration, comic sublimity to heartbreak, is without peer in American literature.

Anyone reading West en toto knows that his descriptions of women are less than pleasant. In point of fact, they’re brutal. Cast most often as shrews, temptresses, succubi and jades, the women of his novels are a distaff chorus of predatory energy, poised to strike. Though he was clearly a lover of the beauty and sensuality of women—again and again in his novels, women are described using striking tropes and phrases; some of his most ardent lyric sparkles are strewn at their feet—West seemed to fear their emotionality and power and rarely missed an opportunity to pour scorn on their intimacy with men: “She thanked him by offering herself in a series of formal, impersonal gestures. She was wearing a tight, shiny dress that was like glass-covered steel and there was something cleanly mechanical in her pantomime.”

Sex, in his books, is always an agon—either primitive and animalistic or the product of a killing combat between men and women: “Her invitation wasn’t to pleasure, but to struggle, hard and sharp, closer to murder than to love. If you threw yourself on her, it would be like throwing yourself from the parapet of a skyscraper. You would do it with a scream. You couldn’t expect to rise again. Your teeth would be driven into your skull like nails into a pine board and your back would be broken. You wouldn’t even have time to sweat or close your eyes.”

In the following famous scene, West, who so often sketched women through the shorthand of an outstanding physical attribute, here achieves a reduction of woman to the pure immanence of the marine: “He smoked a cigarette standing in the dark and listening to her undress. She made sea sounds; something flapped like a sail; there was the creak of ropes; then he heard the wave-against-a-wharf smack of rubber on flesh. Her call for him to hurry was a sea-moan, and when he lay beside her, she heaved, tidal, moon-driven. … Some fifteen minutes later he crawled out of bed like an exhausted swimmer leaving the surf, and dropped down into a large armchair near the window.”

An overmothered child, West eventually developed a gentleman-farmer persona composed of equal parts Ronald Firbank and Buffalo Bill Cody. This calculated public front concealed a fierce ambition: he burned to be successful. He wanted very much to be a big-time novelist, a kind of mitteleuropisch John O’Hara. This being the case, the indifferent popular reaction to his books was a crushing disappointment. After Miss Lonelyhearts, he tried his hand at A Cool Million, a burlesque of the Horatio Alger myth, and the book, not to put too fine a point on it, was a hash. Told in mock-heroic style, its satire was deflected by the jarring period diction and its story slowed by a mass of picaresque improbabilities. West had written it quickly, to capitalize on the very positive critical reaction to Miss Lonelyhearts (fans of which included Edmund Wilson, Dorothy Parker and Thornton Wilder). Chastened by the scathing reviews of A Cool Million, he tried to write some glossy magazine stories to make money and reestablish himself. These were rejected. With F. Scott Fitzgerald’s help, he applied for a Guggenheim, and was again rejected. Disgusted, he pulled up roots, moved to Hollywood and began working sporadically as a screenwriter, limning such classics of the genre as Five Came Back, I Stole a Million and Spirit of Culver. In the meantime, having long associated himself in a vague way with leftist causes, he continued to dabble in fellow-traveling. He published a Marxist poem in Contempo. He worked for the Loyalist cause in Spain. Gradually, he began the process of capillary absorption of the Hollywood milieu which would be parodied with such Westian verve in his next novel, The Day of the Locust.

Unlike Miss Lonelyhearts, The Day of the Locust is not a perfect book. A brilliantly acid portrait of 1930s Hollywood, it suffers from an ambivalence on the part of its author as to the extent of his own self-projection in its narrator, Todd Hackett. The character, a scene painter, remains too emotionally circumspect ever to come entirely alive. And though West’s studies of the human fauna of Hollywood are superbly drawn, the cast of the book lacks the deeper motivational wellsprings of those in Miss Lonelyhearts. They flicker slightly, like country lightbulbs. Nonetheless, West manages scenes of astonishing power. His honest depiction of what William Carlos Williams called “the real, incredibly dead life of the people” is balanced, as usual, with a kind of gloating interest in the vanities and cupidities of human desire and with a morbid fascination and disgust with sex and bodily functions, the essential venality of American life and the human cost of the dream factory called Hollywood. His gallery of Tinseltown grotesques speaks with voices which, in the words of Edmund Wilson, have “been distilled with a sense of the flavorsome and the characteristic which makes John O’Hara seem precious.”

The book, now considered a major American novel, was a flop at the time and, despite some good reviews, sold less than 1,500 copies. His publisher, Bennett Cerf, told West that The Day of the Locust was a failure for the simple reason that women readers—no doubt due to the violence with which they were depicted in the book—didn’t like it.

In 1939, West wrote to F. Scott Fitzgerald: “Somehow or another I seem to have slipped in between all the ‘schools.’ My books meet no needs except my own, their circulation is practically private and I’m lucky to be published. And yet, I only have a desire to remedy all that before sitting down to write, once begun I do it my way. I forget the broad sweep, the big canvas, the shot-gun adjectives, the important people, the significant ideas, the lessons to be taught, the epic Thomas Wolfe, the realistic James Farrell—and go on making what one critic called ‘private and unfunny jokes.’”

A little over a year later, while returning with his new wife from a hunting trip, West was killed in an automobile accident, leaving behind a single perfectly lit room in the house of American prose. He was thirty-seven.