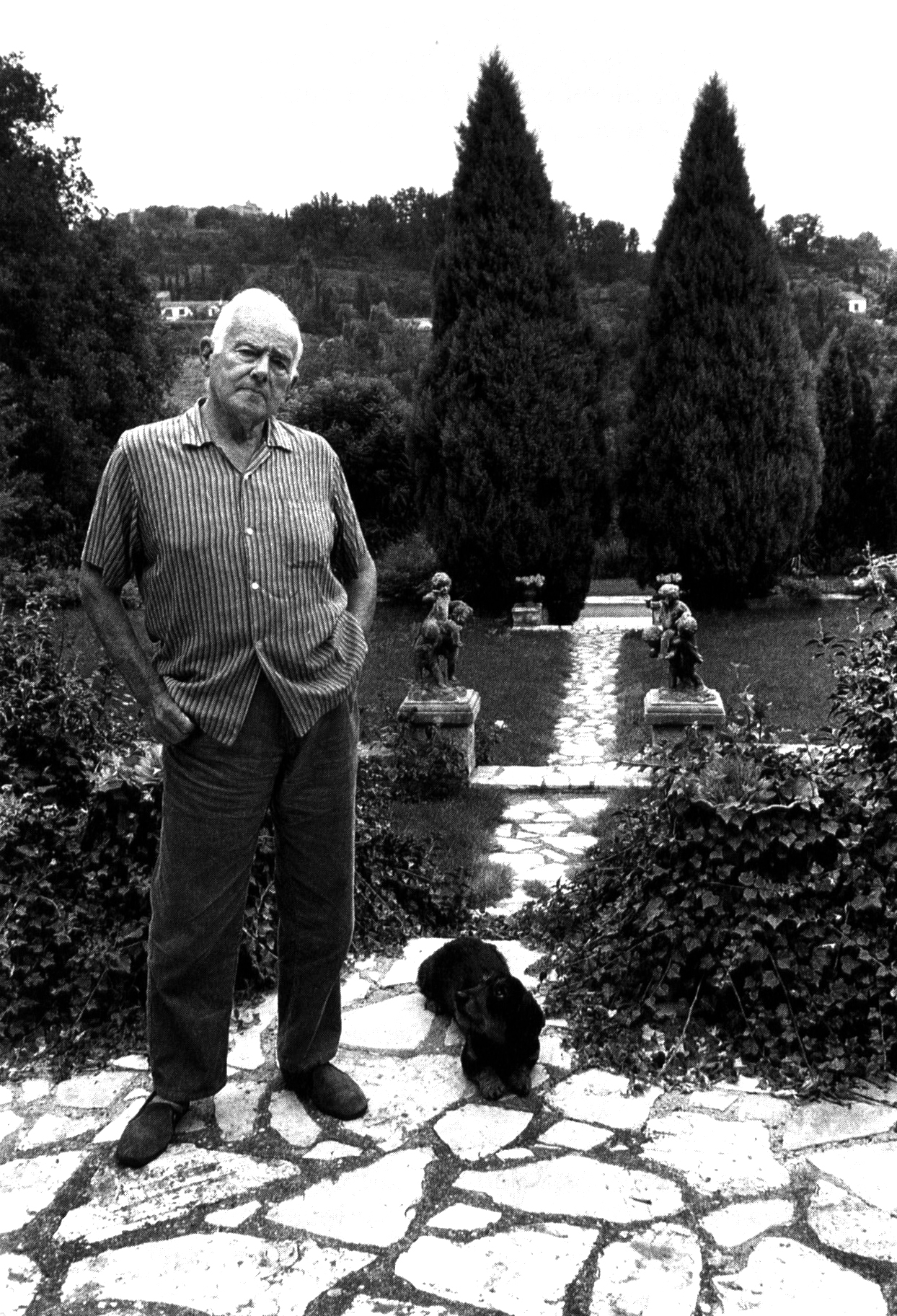

Frederick Piokosch. Provence, France, 1986. Photograph by Nancy Crampton.

THE FATE OF FREDERICK PROKOSCH’S REPUTATION is a hard lesson in the laws of vagary. In 1935, the twenty-nine-year-old won international acclaim with one of the century’s most eccentric and iridescent novels, The Asiatics, a work hailed as a masterpiece by the likes of Thomas Mann, Albert Camus and André Gide. To this day, The Asiatics is among the most read American novels in France, where Prokosch has always been adored, and French translations of his books were omnipresent in the Latin America of the fifties and sixties, demonstrations of lyrical hyperreality which the magical realists took to heart.

Yet Prokosch’s fame in the land of his birth is all but extinct. Although Warner Brothers made his wartime novel The Conspirators into a 1944 Hedy Lamarr movie complete with a super-spy hero named The Flying Dutchman, Prokosch’s aristocratically aloof and resolutely internationalist fiction failed to mesh with the growing parochialism and bloated realism of postwar American culture. In a literary mall now gone mad with gut-wrenching confessions, family incest and TV overspill, he is more exotic than ever.

In fact, America has little time for its own exiles now, and even less for landscapes which are not its own, unless they can be decked out with winsome “third world” political credentials determined by a connection with ethnicities or ideologies largely present in its own interior. The psychological voyage out into the exterior world of an “undeveloped” existence must now drip with sanctimonious excuses and pseudo-political reportage. The lonely, austere odyssey of a Paul or Jane Bowles or a Frederick Prokosch—Americans trying deliberately to expand or sabotage their inherited cultural wiring in places which have no relevance whatsoever either to American guilt or to geopolitical self-interest—is now only vaguely irritating and confusing. Recently, it took the efforts of an indignant Spanish schoolgirl to have Jane Bowles’s remains disinterred from under a planned parking lot in Malaga. Perhaps the greatest American woman writer of the twentieth century doesn’t even have a grave largely because she had the whimsical impertinence to die abroad. It would be like Colette being buried under a Grand Union in Poughkeepsie and no one in the French-speaking world caring less.

Of course, the cruel roulette of Fame has its necessarily unfortunate turns. Not every deserver gets a winning number. Is Prokosch silenced because he turned his back on the gigantic hugger-mugger of American suburbia which has given other postwar writers their chloroformed but instantly recognizable field of dreams? One cannot say. Perhaps the gentle and the aloof simply get pushed aside, unprotesting, and resign themselves to their grim transparence in a cultural landscape dominated mainly by airports.

In a long and affectionate essay on Prokosch for the New York Times Book Review fifteen years ago, Gore Vidal, considering the propensity for Amnesia (America) to forget yesterday’s dinner, describes a hilarious evening long ago in the sixties when the already forgotten Prokosch visited Vidal in the Hudson Valley. The two attend a party of “hacks and hoods” from the local grove of Academe, who snub Prokosch mercilessly. “They knew he had once been famous in Amnesia but they had forgotten why.” Prokosch listens politely to the absurd literary chit-chat, in the course of which a tenured radical declares the classics of Western civilization to be irrelevant and oppressive. Prokosch then quietly begins to recite in Latin a passage from Virgil. The room grows “very cold and still.” “It’s Dante,” one of the professors murmurs to his wife. “Those words,” Prokosch says when he has finished, “are carved in marble in the gardens of the Villa Borghese in Rome. I used to look at them every day and think, that is what poetry is, something that can be carved in marble, something that can still be beautiful to read after so many centuries.” Stunned silence.

So Prokosch has entered the sinister twilight zone of nonfame, or postfame, a state so terrifying and colder-than-death to Americans that they cancel out all trace of such catastrophic possibilities, whatever the glory of the allotted fifteen minutes. Yet with canons tumbling and rising again, and general insurgence setting off corks in all directions, it is now a good time to become eccentric and maraudingly revisionist readers. Prokosch speaks to us with his lightning-flash peacock-dandy prose, his gorgeously lithographic travel writing, his luminous and brush-quick descriptions, his thirties aerodynamism and lyrical sleekness. He wanders homeless through imaginary landscapes shaped like continents that seem to be geographically real until we realize that Prokosch never travelled in any of them. Prokosch wrote most obsessively about Asia, not in the old spirit of ex oriente lux, but as a way of enacting a purely internal voyage which had to have some outward form. In fact, his books always wander through worlds that are thoroughly hybrid and unreal, populated with characters as extravagantly miscegenated as those of Star Wars or Alice in Wonderland.

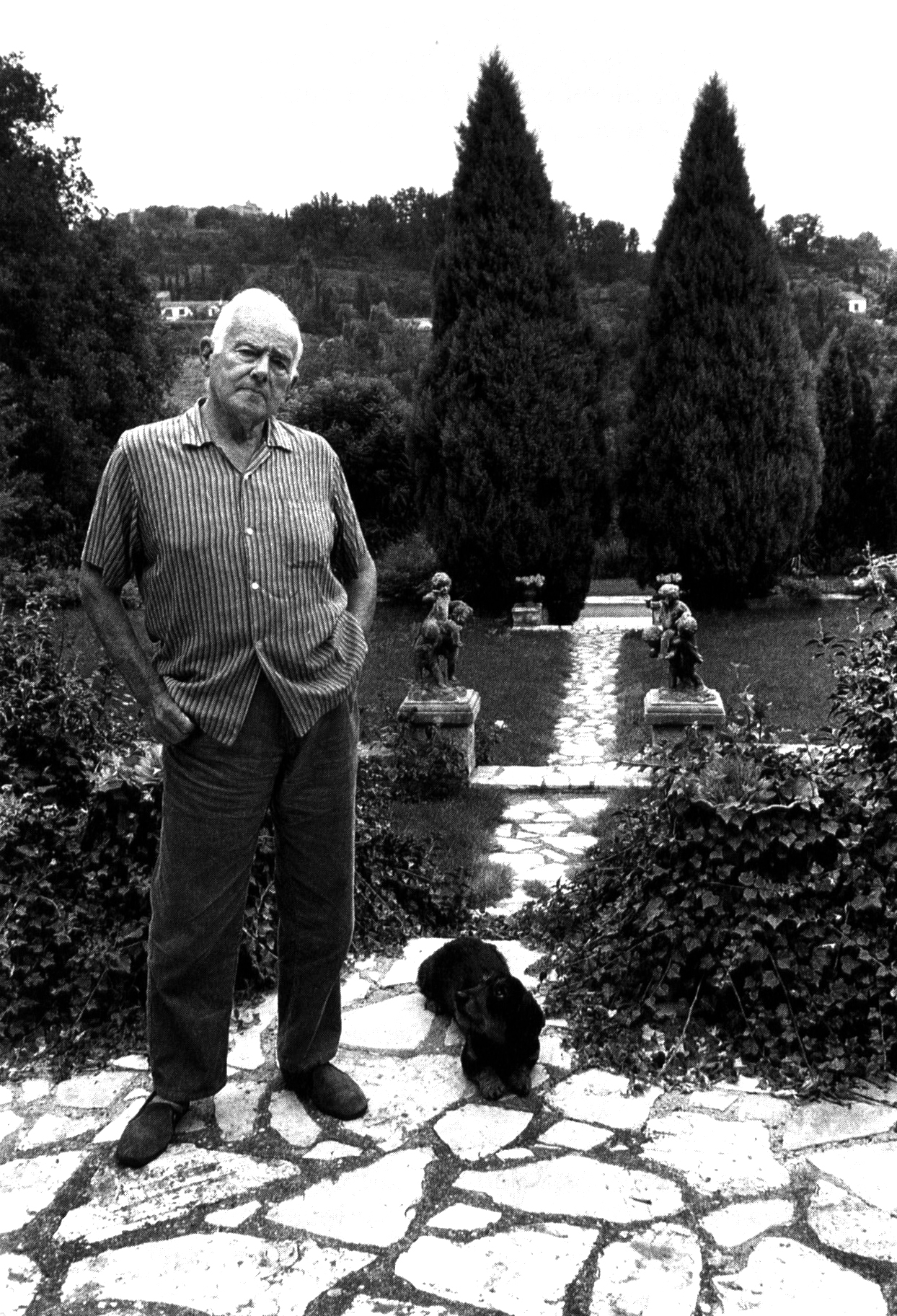

Frederick Piokosch. Provence, France, 1986. Photograph by Nancy Crampton.

I first came across The Asiatics in a bookstore in Marrakesh many years ago when I was a student spending a summer at Ouazazarte in the Sahara. It was the ideal book for a solitary odyssey into the desert at the far side of the Atlas and I remember reading it in the bouncing back of a bus hauling its way over the gloomily Gothic peaks of Tizin-Tichka, the highest mountain in Africa. At once I found myself with the very opening images of the book: a night watchman singing to himself in a street in Beirut, an air filled with mosquitoes, shabby Ford cars, silent prostitutes standing on the far side of the street and an old man in whom “loneliness had sharpened [the] instincts.” The swift cinema scenes unconnected by logical narrative swept me along roads almost exactly like the ones passing below my own window. The road to Damascus with its beautiful Syrian boys, its tin-roofed slums and villages slumped among giant cactus, caves filled with outcast families and then the sad apricot trees of Damascus and deserts rustling with locusts, “a pathetic sort of antiquity … cheap with age.”

The novel is not a novel, of course, but a hallucination, its scenes bursting as lurid flashes of light and feeling. It had the fluid linear form and endless embellishments of an alien expression, like Arab lute music itself. It seemed to me that he had entered into the deep, subterranean flow of landscape, an intuitional complicity which operates upon us as an electrical force field disturbing in some as yet unexplained way the “internal” senses. Hence his light-flashes are not really descriptions. In all of Prokosch’s books, these moments of illumination appear as surges in a mysterious flow of intuitive impression which is never stable or solid.

In Storm and Echo, for example, we find this glimpse of an alien territory: “On and on. The light of the moon seemed to penetrate the waste, to grind it into something shrill and homicidal. It wasn’t land we were crossing, it was some awful spiritual concoction, an embodiment of bitterness and pain, a scene of pure melancholia.”

Well, I took The Asiatics with me to Ouazazarte and on to the oasis village of Tinerhir, a surreal eighth-century village made of thousand-year-old mud where I read it walking up and down through a spectral Atlas landscape on my way to the nearby Gorges du Todra. It seemed to me that I was in a purely Prokoschian place. The same crazy outcasts sleeping in dried oueds, the same oases and plantations, the same disorientated Westerners and fluid, rapierlike interactions between strangers wandering along decrepit roads. In fact, I think of The Asiatics as the first road movie, and by far the most interesting. “Nothing is as beautiful as a road,” George Sand once said, and I think of it as Prokosch’s motto. He is a sly late Sufi wandering alone along roads where he might find fiery miracles, visions, sudden encounters, mystical friendships and perhaps even the severed head of the venerable Shams so ecstatically imagined by Rumi.

Both The Asiatics and the later memoir, Voices, are built around sudden encounters with strangers, meetings as epiphanies that arise, reach a quick crescendo of intimacy and illumination, then melt away into a formless flow which the writer disdains to turn into anything cumulative. The result is something curiously archaic, like Buddhist fables or the eighteenth-century conte philosophique. It has also earned Prokosch a certain amount of rebuke, with a predictable string of accusations: “precious,” “self-glorifying,” “contrived,” etc. No doubt there are moments when the process fails. The meetings in Voices with a galaxy of the great, worthy and wise do seem a little fable-like and precious at times, as if the habit of writing down every conversation in progress, as a bemused André Gide points out to his young interviewer, had become a peculiar, voyeuristic tic.

But the center of gravity in Prokosch is his solipcism, which dispenses with any pretenses to writerly “relevance” to historical realities. Here, it is the quest of the writer that matters, nothing else. Thus, every vibrant encounter with other “voyagers” has a self-evident profundity. As Prokosch looks back to his childhood, we see Thomas Mann’s leonine head through his eyes, framed by misty hockey fields as he visits the Prokosch home (Prokosch’s father was a famous professor of Indo-European linguistics). We see, too, the young Frederick creeping up behind James Joyce at Sylvia Beach’s bookstore in Paris, noticing the grubby elegance and the mode of handling a teacup. Auden in a Turkish bath in New York looking like “a naked sea beast” with his “embarrassed-looking genitals,” Lady Cunard and Hemingway dueling it out in Paris to the thunder of Hemingway insights such as “There’s a pro and a con to Russia, as with all these fucking countries.” “There are three different kinds of happiness,” intones Peggy Guggenheim in one chapter, and proceeds to tell us what they are, though without much effect. In an excruciating interview with Virginia Woolf, the young American poet is made to feel flylike as he sits in a lugubrious room facing what must have been a withering and aloof stare, which nevertheless does not obscure her “exquisite beauty.” It is all part of a deliberately Twainlike peregrination overflowing with canny naïveté and acid detail.

Some of the most enjoyable episodes are those that deal with his hushed encounters with cultural high priests like F. R. Leavis and fellow lepidopterists like Nabokov. “Eliot?” snaps Leavis at high tea in Cambridge. “He is gratuitously and fortuitously obscure. Obscurity has been known to conceal an inner vacuity.” Nabokov we see in a darkened and gloomy Swiss hotel sitting mysteriously in a large armchair. “I felt a dark suspense, as though confronted by an oracle.” Nabokov tells him that he has tried to see the world through the eyes of an insect; they discuss the Agrias butterflies of the Amazon, the exile’s voice “stained by a harrowed anonymity,” and Prokosch tells of how he climbed a mountain in Corsica mentioned in a Nabokov book in order to pursue Europe’s rarest butterfly, the Papilio hospiton, the Corsican Swallowtail. The beast’s color, he observes quietly, is not quite that described by the brilliant stylist of Glory.

In this same passage, Nabokov tells Prokosch that “America is in a continual state of trance. Even the mountains and the forests have an air of the hallucinatory.” And that the artist is inevitably an exile, whether externally or internally being largely a matter of the complexion of each individual. “And the exiles end by despising the land of their exile.” For Prokosch too, perhaps above all, nostalgia, roaming quest, immersion in the hallucinatory pervade the writer’s inner air. As Nabokov settles in Lucerne, Prokosch gets a little house for himself in Grasse in southern France. “How glorious,” he writes, “to grow old!” Exile, oblivion and contentment consonant with an overwhelming recognition of the endlessness of all roads. A spirit of mystical spontaneity could demand nothing less.

In his preface to his early novel The Seven Who Fled, Prokosch tells how he came to imagine seven Western fugitives on the highroads of Asia, shadows who imprint their meanings “on the deserts of Asia like shapes on a film.” Coming out of “a marvellous dream” filled with burning mountains one night in 1935 in Mallorca, he looks down at the Bay of Alcudia “black as the fur of a yak” to see seven fishing boats with seven torches burning on the horizon. Some meaning, “a flaw in a twilit crystal,” sets his reverie in motion and he begins to walk along seven roads “in a fit of love.” The result is a typical Prokosch book: a fantasy of escape edged with the hardness of an eye which tirelessly hardens its otherworld with glass-bright imagery and sulphurous fear.

Do these peregrinations acted out with the pen and not the feet have the power to compete with those of Marco Polo or Bernal Diaz? We will not really know. It is clear only that Prokosch was himself one of those who fled, who sought “a mysterious and revelatory depth” on roads that can only be invented and who became as he went one of the rarest and most agile butterflies of an Amnesia which no longer collects.