1

Operative Witchcraft

Definitions and Practices

Magicians strive not to be counted among the could have beens, The would have beens and the should have beens.

Magic is an integral part of culture. It has often been ignored by historians who, not believing in its efficacy or even recognizing that in the past many people did believe, have dismissed any belief in it as beneath mention. Alternatively, magic and the occult sciences, when they have been mentioned, have been portrayed as worthless superstition or irredeemably diabolical and evil, unspeakable rites to be shunned, lest they taint the reader. But to present magic as a dangerous subject that ought to be censored lest it seduce the reader into criminality is unhelpful, for it pushes students of magical history into a ghetto when students of human depravity and violence, such as war and crime, are welcome in the mainstream. Magic played a significant part in shaping people’s lives. Magic is an integral part of our cultural heritage, ancient skills, and wisdom and a perennial response to universal situations and problems.

The expression “ancient skills and wisdom,” which was coined in Cambridge in 1969 by John Nicholson, describes the knowledge, the abilities, and the spiritual understanding of how to do things according to true principles. The ability to practice these ancient skills and wisdom requires an understanding of one’s personal place in the continuity of one’s culture over thousands of years. It necessitates being present in one’s own tradition based on place and the accumulated knowledge and skills of countless ancestral generations as well as being open to new things and how they can be harmonized with the old. Ancient skills and wisdom are timeless because they are based on universal principles, and these basic essentials of existence and of human nature do not change. Western occult philosophy embodies these ancient skills and wisdom. It has an enormous corpus of interconnected traditions and currents that have been expanded, developed, and refined through time, as has the definition of what witchcraft is and who are the witches. Some of those called witches were people who knew particular techniques—ways of doing things and the tricks of the trade that were unsuspected and unknown by most people. These techniques are comparable to those of the art and activity that were transmitted through apprenticeship to members of craft and rural fraternities, but they were less obviously useful than the crafts of the shoemaker, the seamstress, the miller, or the ploughman.*1

Practitioners of vernacular magic were readily accessible in seventeenth-century England, despite the Witchcraft Act of 1604 (see chapter 5). In 1621, Robert Burton wrote in his The Anatomy of Melancholy, “Sorcerers are all too common; cunning men, wizards and white-witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought unto, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind” (Burton [1621] 1926, vol. II, i, I, sub. I, 1926 ed., v. 2, 7). Burton was, of course, totally disapproving because he believed that these practitioners were using forbidden powers, so it was not lawful to resort to them for cures, under the principle “evil is not to be done that good may come of it.” But people who had no recourse to any other medical or legal assistance were, of course, clients of white witches, cunning men, wizards, and quacks, whether or not they were officially legal.

Fig. 1.1. Seventeenth-century image of a witch

In the second edition of his A Glossary of Words Used in the Wapentakes of Manley and Corringham, Lincolnshire (1877), Edward Peacock gives the entry: “White Witch: A woman who uses her incantations only for good ends. A woman who, by magic, helps others who are suffering from malignant witchcraft.” (Those who practice beneficial magic are, however, generally called wise women or wise men). A working definition of the various kinds or functions of witches was in use in the West Country of England in the nineteenth century. In her Nummits and Crummits (1900), Sarah Hewett published the distinction between three recognized categories of witchcraft: black, white, and gray. The black witch was malevolent, bringing every known evil on others; the white witch, in opposition, employed countermagic against black witchcraft. White witches, however, made money out of their craft: they charged their clients to take off the spells.

The third category was the gray witch, which Hewett considered worse than either the black or the white, for the gray witch has the power to put spells on people, to use the evil eye, to curse, and to bring bad luck. But also she has the power to heal and bring benefits. Writing about the same region in 1899, H. Colley March defined a wise man or wise woman as one who, without fee or reward, tells folk how to overcome witchcraft. This fee is the subtle distinction between the wise woman and the white witch inferred in Peacock’s definition. Perceptions, of course, have never been fixed. Writing about Devonshire charmers in 1970, Theo Brown noted that charmers of warts and so forth would never accept payment because to take money would deprive them of their power. Brown observed that this was a modern development, as the white witch of old was always a professional and charged considerable fees (Brown 1970, 41).

In addition to the overt practitioners of what is considered to be witchcraft proper, the name witch is given to certain men from the Confraternity of the Plough in their Plough Monday disguises. Thus, in Northamptonshire, “Witch-Men, n. Guisers who go about on Plough-Monday with their faces darkened.” In Northamptonshire, Plough Monday had the alternative name of Plough Witch Monday (Sternberg 1851, 123).

Witches and witchcraft are not necessarily synonymous. Some labeled the magic performed only by those labeled as witches to be witchcraft, while those not labeled as witches were seen to be practicing magic against the machinations of the witches. More confusingly, those performing countermagic against witchcraft were sometimes also considered witches, as in the case of white witch versus black witch, but others performing the same countermagic, both professionals and amateur individuals, clearly did not consider themselves to be practicing witchcraft at all. In 1705, in his Discourse on Witchcraft, John Bell warned his readers to “guard against devilish charms for men or beasts. There are many sorceries practiced in our day. What intend ye by opposing witchcraft to witchcraft, in such sort when ye suppose one to be bewitched, ye endeavour his belief by burnings, bottle, horse-shoes and such-like magical ceremonies” (Lawrence 1898, 113). The definition of witches as people belonging to a secret organization confused the issue of the forms of folk magic that permeated the whole of society, with specific practitioners having their own specialized forms of magical practice.

Recorded instances of British traditional practitioners from the seventeenth century onward who used at least some magical techniques in common with that of operative witchcraft describe them by various names, many of which are generic, while others focus on a particular characteristic or skill: black, white, or gray witch; wise woman; old wife; handywoman; charmer; cunning man; clever man; doctor; wise man; wizard; warlock; magus; magister; magician; professor; mountebank; lijah; conjuror; conjuring parson; planet reader; quack doctor/doctress; wild herb man; root digger; root doctor; herbsman; toadman/toadwoman; toad doctor; tuddy; horse doctor; cow doctor; seventh son of a seventh son; boggart seer; skeelie folk; and so on.

These categories are in addition to those of a more organized and speculative kind, from Christian mystics, astrologers, thaumaturges, Jewish mystics, kabbalists, and others whose expertise lay outside the bounds of orthodox religion and, later, science. Society has always been pluralistic in terms of belief, doctrine, and practice, even in times when authorized worldviews were imposed by force with the sanction of violence on violators.

Equally, society has always been full of forbidden and unrecorded activities, rule breaking, illicit practices, fiddles, rackets, scams, hokkibens, confidence tricks, bribery, and corruption. Practitioners of these activities always deny all knowledge when suspected; they are always uncooperative with those who ask questions. Those with specialist knowledge, which gives them a livelihood, power, or both, are always covert and secretive about their knowledge and know-how. It is worth keeping quiet and not letting on. This air of mystery simultaneously attracts customers and frightens people. Catherine Parsons, a folklorist from Cambridgeshire, noted in 1952, “Witches liked to be credited with the power of evil so that the credulous would pay for protection and people’s misfortunes would add to their reputation” (Parsons 1952, 45). But the opposite could happen too, with people getting the blame for misfortune when they never claimed to have powers. Henry Laver, writing in 1889 about Essex half a century earlier, remembers Mother Cowling, “an old harmless woman at Canewdon who was credited with the possession of fearful powers and was blamed for others’ ills” (Laver 1889, 29).

The charter among villagers was never to talk about witches and their activities, but the research work of the folklorist is to investigate. In 1925, an old woman in whom the Norfolk folklorist Mark Taylor was interested, put the toad on him (Taylor 1929, 126–27), and in 1952, Parsons noted, “I flouted the witches in 1915 by reading a paper on witchcraft before the Cambridge Antiquarian Society at some risk to my well-being for one should never talk about witches if one wants to keep free of their craft” (Parsons 1952, 45).

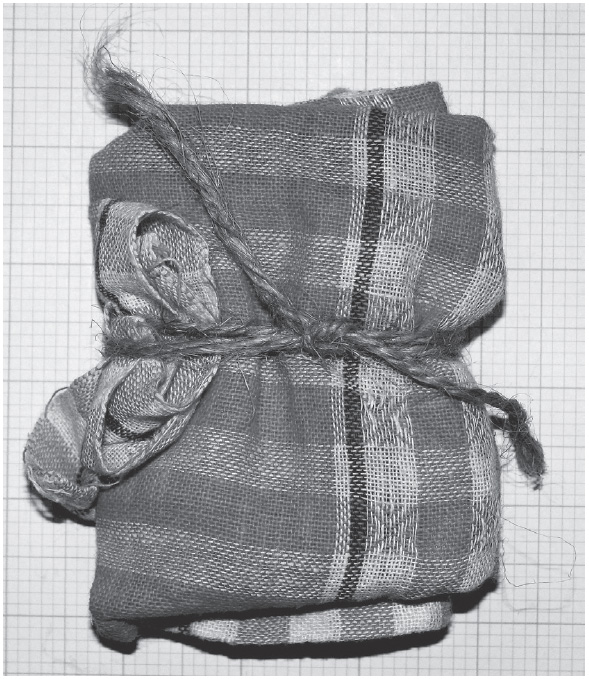

Fig. 1.2. Toad mummified in wrapped bundle, Cambridgeshire