WHY MEDIUM-RARE MATTERS

There comes a point during the cooking of steak when everything comes into perfect, delectable alignment. The juices have loosened but are stable, the fat is just the right sort of melty, the meat’s fibres have become defined but not overly so, and the meat is supple while the crust is dark and full of complex, savoury flavour. If this point of alignment has a temperature, I would name it 125°F (in the centre of the steak), or even a little lower. The French, appropriately, call this simply à point, which translates to something a bit under medium-rare in North America.

The North American standard of medium-rare is generally in the 130°F to 135°F range. The reasons why I recommend cooking a steak to a few degrees below that are threefold:

- Your steak will simply lose too much juice when cooked to above 130°F.

- Your steak will continue cooking a few degrees higher after you remove it from the heat, even without tenting or wrapping.

- An opportunity to taste the full potential of steak is lost when there is no rare steak left in the bite, and that seems a shame. When a bite of steak has a mostly even but still varied level of doneness, its full potential is realized.

I find that most medium-rare steak eaters actually do like a certain, if small amount, of rare steak in the very middle. Generally speaking, when any given whole steak is cooked to 120°F, much of it will also reach medium-rare or even medium, 5 to 10 degrees hotter. Indeed, an important part of eating a rather well-aged rib steak or porterhouse is experiencing the varied textures in a single piece of meat: some mostly uncooked meat amid well-done, crusted meat in the vicinity of medium-rare meat, where the juices are liberated in a mouthful. It’s a nearly unfathomably pleasurable experience.

A single steak can contain several different types of tissues. For example, a slice of sirloin consists of three or more muscles, which cook at different rates and which behave differently at different levels of doneness. Rib steak has three adjacent muscles. Porterhouse consists of two distinctly different muscles separated by bone. Cooking all of these steaks to an average temperature of 120°F takes care of these variations. Some parts of the steak will be more red and softer, others will be darker and coarser, and other parts—most parts—will be what a typical enthusiastic steak eater (in my experience) knows to be medium-rare. Yes, some rareness will endure closer to the bone or inside denser tissue, but isn’t that better than a medium-well done steak?

After a steak has been removed from the heat, a certain amount of thermal inertia continues to propel its temperature upward. The hotter and longer the steak was cooking, the more inertia there is, and the longer it will take for the temperature to level out and then cool. That’s why the slow, reverse-searing method requires less resting time and why a steak pulled from the fire as it approaches 125°F is going to finish close to 130°F in any case, before it begins to cool.

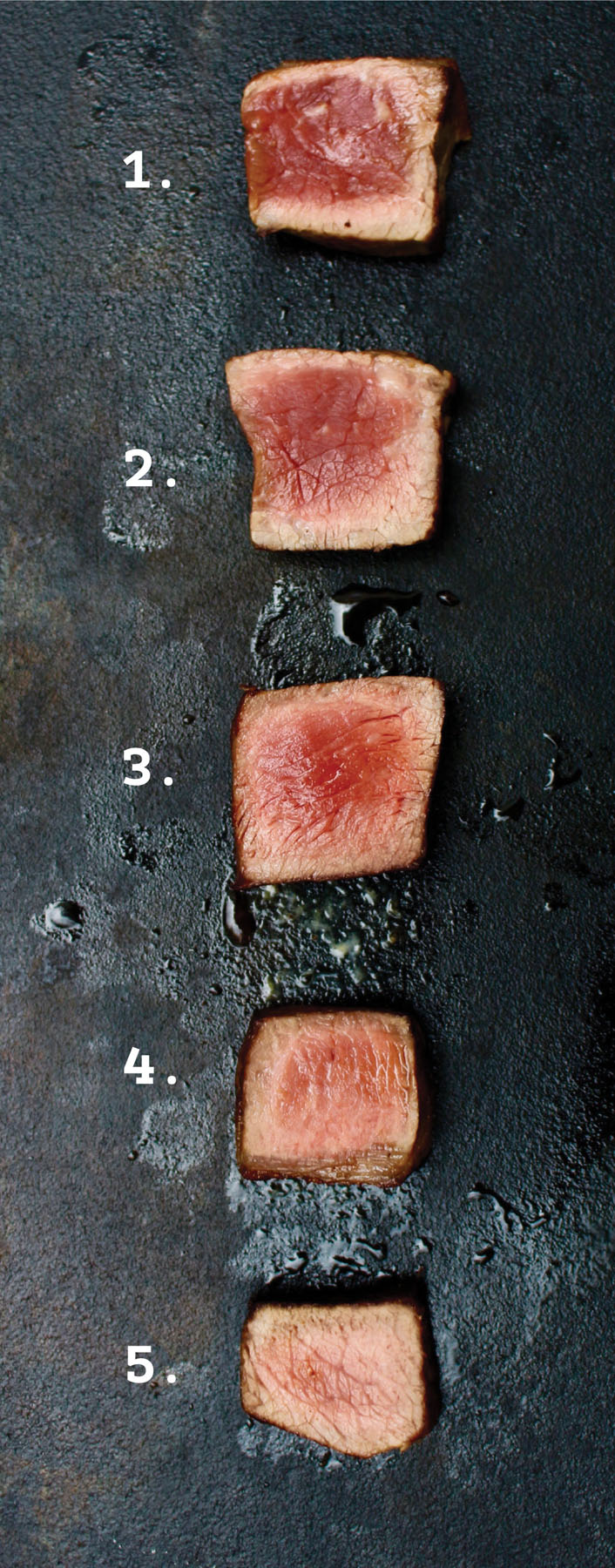

STAGES OF PERFECTION

Steak doneness (“colour” to a grill cook) can be a sensitive business. For the purposes of this book, and I think in the world at large, this guide should give you all you need to hit the colour you are looking for, whether cooking at home or directing your server in a restaurant.

1. BLUE

The steak is very much raw, and just a little warm to the touch. If the whole steak is cooked this way, it is only seared or very quickly charred. The middles of rare, à point, and medium-rare steaks are very often on the raw side, too. There is very little juice in a steak that is blue all the way through, though; the juice is still well contained within the structure of the steak and none of the fat has melted. Not many steaks are that good blue, but there are exceptions, given your mood. I’ve had terrific well-aged steak quickly seared and served to me barely warm—a sublimely dark and richly concentrated filet mignon springs to memory. I still secretly wished it had been cooked 2 minutes longer.

INTERNAL TEMPERATURE: 85°F TO 100°F

2. RARE

The steak is well cooked close to the surface, with fibres beginning to loosen partway through, and much of its interior is still raw, but warm. Some crust, and some juice, since the cooked part of the structure of the steak has been disrupted. Very good aged steaks can be excellent rare.

INTERNAL TEMPERATURE BEFORE RESTING: 100°F TO 115°F

3. À POINT

This is, as you might have imagined, how the French might order their steak and how I prefer it most of the time: “on the point of” … perfection, in my view. It takes full advantage of the silky texture of steak with a substantial but not dominating, partially raw, warm middle, loosening the fibres just enough to free the juices and melt the fat while giving it enough time to develop a tasty crust. I nearly always try to cook steaks for myself to this level of doneness, and order steak “rare to medium-rare” in restaurants.

INTERNAL TEMPERATURE BEFORE RESTING: 115°F to 120°F

4. MEDIUM-RARE

My second favourite “colour” of doneness, medium-rare is really the slightly more done, go-to equivalent of à point everywhere in the world outside of France. There can be a noticeable bit of warm, partially raw meat in the middle, but otherwise the fibres are well loosened, releasing their juices but still holding some. Much of the time the steak will just start to feel grainy near the surface and partway through, but a great medium-rare steak can be evenly cooked and juicy throughout.

INTERNAL TEMPERATURE BEFORE RESTING: 120°F to 130°F

5. MEDIUM

Some steaks get to medium and perform pretty well. They are almost always quite fatty and engorged (like prime rib). For my money, though, this is the absolute end of the story, since anything after this point is simply overdone. If you like meat that way, I think you would do much better with a slow roast, braised meat, or low-and-slow barbecue, which, as so many of us already know, can be supernaturally tasty. The texture of medium grilled or pan-fried meat can be pretty grainy, especially for lean cuts. A little medium meat is part of what happens to big steaks on the grill at their extremities, and that’s okay, since they are generally tempered by an extra-juicy environment and in the vicinity of rarer meat. If the whole steak is cooked to medium, the juice has mostly left the steak and is on the plate, or lost altogether to the coals.

INTERNAL TEMPERATURE BEFORE RESTING: 130°F to 135°F

The photo above shows pieces from the same cut of steak (from the prime rib). Notice how the slices get smaller as they are more cooked. This is because the steak loses its juices (water and fat) the longer it is on the heat. The exact temperatures of the steak slices in the photo, from bottom to top, before resting: 92°F, 104°F, 119°F, 126°F, 135°F.

© 2018 by Rob Firing