A MEDIEVAL MYSTERY, by Peter James Quirk

Being the monarch of a modern European country is usually a secure, hereditary position. This, however, was not always the case. Czar Nicolas of Russia was assassinated with his entire family less than one hundred years ago. Queen Elizabeth of Great Britain, by contrast, is much respected and after more than fifty years on the throne, remains comfortable in her role as Britain’s titular head of state. She sits down to her meals without fear of being poisoned and she sleeps at night without the remote possibility of being awakened by hostile troops and dragged off to the Tower of London.

Of course, life on the British throne was not always so harmonious. History informs us that during the Middle Ages, being the king of England was somewhat akin to being head of the Gambino crime family. Fortunately, Elizabeth’s ancestors were up to the task. Indeed, the guiding principles of the Plantagenet kings, who presided over England for approximately three centuries (from 1215 to 1485), were remarkably similar to those of Lucky Luciano or John Gotti.

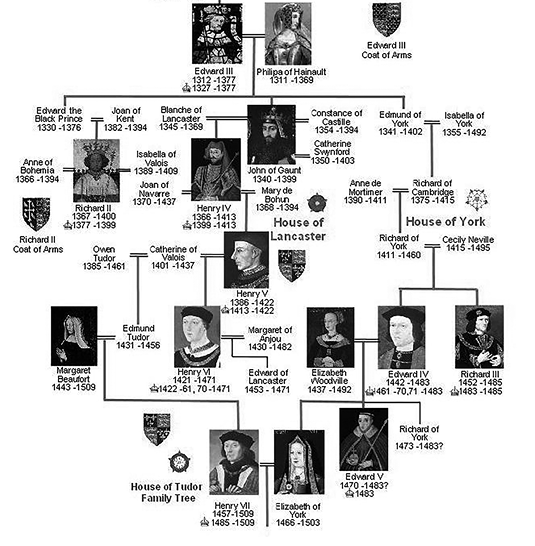

Their routine savagery peaked spectacularly in the late fifteenth century with a mysterious episode that could easily be the worst atrocity of the entire Plantagenet Dynasty: the disappearance and subsequent murder of the young Princes in the Tower. [The family tree on the following page shows only those members relevant to this narrative.]

The principal suspect in this medieval mystery is their uncle Richard (King Richard III). However, there is a compelling case, supported by a great many people, including eminent historians, for his innocence.

I was reminded of this crime while researching Richard’s career and accomplishments for a novel. And I found that the record of his relatively short life—he was thirty-two when he was killed—is completely at odds with the universally-accepted version presented by William Shakespeare in his iconic play, “The Tragedy of King Richard III:”

“Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York” (I.i.1-2)

House of Plantagenet

Unquestionably, the most monstrous of all the crimes attributed to him in that monumental work were the murders of his two young nephews, King Edward V and Richard, Duke of York—the Princes in the Tower:

“Shall I be plain? I wish the bastards dead,

And I would have it suddenly performed.” (IV.ii.18-19)

This grisly double murder was even the subject of a crime novel written in 1951 by the distinguished Scottish mystery novelist Josephine Tey. In Tey’s novel, her protagonist, Detective Inspector Alan Grant lies in a hospital bed with a broken leg. With nothing else to do, Grant mulls over pictures of historical figures brought to him by a friend to help alleviate his boredom.

When Grant draws up a favorable psychological study of one of the portrait’s subjects, he is astounded to learn that this stately individual is no other than the arch-villain of English history, King Richard III. Grant then proceeds—with the timely assistance of nurses, friends, and an American student, who obtains research materials for him and discusses the case with him at his bedside—to prove that Richard is completely innocent of all charges. The title of the novel, “The Daughter of Time,” is taken from a quote attributed to Galileo: “The truth is the daughter of time, not of authority.”

So let us examine the known facts of this heinous crime beginning with the political situation: In the waning years of the Middle Ages, England was suffering through a series of fratricidal conflicts called the Wars of the Roses. During these wars, two branches of the Plantagenet family, the House of York (white rose) and the House of Lancaster (red rose), opposed each other for the throne.

The seeds of this struggle were sown a century before, when the Black Prince, the eldest son of King Edward III, died a year before his father. Edward III’s death in 1377 placed the Black Prince’s young son on the throne. This boy, King Richard II, was surrounded by envious and covetous uncles, notably John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (third son of Edward III) and Richard, Duke of York, (fourth son of Edward III). Edward III, it must be remembered, was the fun-loving Plantagenet who, in 1338 declared himself the rightful king of France, thus precipitating the Hundred Year’s War.

During Richard II’s short unhappy reign, amongst other ill-considered decisions, he banished John of Gaunt’s son, Henry Bolingbroke, from England. And when Bolingbroke gathered an army around him and returned to England in 1399, he defeated Richard II’s forces in battle, imprisoned Richard and declared himself King Henry IV—much to the irritation and envy of his Yorkist cousins.

Flash forward to 1460 when Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, (great-grandson of Edward III) took advantage of the then Lancastrian king’s (Henry VI) mental illness, raised his standard and declared himself the rightful king of England. He was killed almost immediately, unfortunately, along with his second son Edmond, at the Battle of Wakefield.

Richard’s eldest son, the eighteen-year-old Edward, immediately took up his father’s cause and proved to be a military genius. He defeated the Lancastrians in a series of battles and assumed the throne as King Edward IV in 1461. Edward was forced to flee England briefly in 1470, when some of his key allies switched to the Lancastrian side. When he returned some months later, however, with his young brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III) at his side, he defeated the Lancastrians, executed Henry VI and ruled England in relative peace until his sudden death in 1483.

We now return to the Princes in the Tower, King Edward IV’s sons: twelve-year old Edward (now King Edward V) and Richard, Duke of York (nine). Their uncle Richard was named Lord Protector under the provisions of the late king’s will and as the Lord Protector, the loyal Richard had already begun preparations for the coronation of the young king when an influential bishop raised a crucial objection.

This bishop testified that King Edward—a notorious womanizer—had entered into a religious ceremony called “Troth Plight” with a young noblewoman before he married the boys’ mother. This ceremony, which was legally binding, especially when followed by consummation—the noblewoman in question was still alive and able to testify—put King Edward’s marriage to the Princes’s mother in doubt, and thus the legitimacy of the Princes. This accusation, if substantiated, would make their uncle Richard, under the English rules of royal succession, the legal king.

Enter the English Parliament. Parliament had just witnessed several years of relative peace after more than a decade of civil war, and they were understandably fearful of placing a twelve-year-old boy upon the throne. So, given the opportunity to bypass the unproven boy for a tested warrior and administrator—Richard had fought loyally and successfully at his brother’s side and governed the North of England prudently in his name—Parliament wrote Troth Plight into law and handed Richard the crown.

According to the Richard III Society—a group dedicated to restoring Richard’s good name historically and theatrically—this law eliminated any motive Richard might have had to assassinate his nephews. It was certainly enough evidence to satisfy Josephine Tey’s bed-ridden detective. However—and this is a big however—the fact remains that Richard sent the two boys to the Tower (of London), which at the time, was a royal residence and not a prison, but after August, 1483 they were neither seen nor heard from again. Richard, of course, had ample opportunity during his two-year reign to show they were alive and well and had never done so. (Their bodies were discovered a century later, buried under a staircase, during a renovation at the Tower.)

There is another leading suspect, however: Henry Tudor, a distant illegitimate Lancastrian with huge ambitions, who defeated and killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field:

“A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse” (V.iv.7)

This battle ended the Wars of the Roses and Henry claimed the throne as King Henry VII.

In order to unite the country and consolidate his position as king, Henry undertook to marry the Princess Elizabeth, oldest daughter of Edward IV and elder sister of the Princes in the Tower. But under the parliamentary Troth Plight law, Elizabeth was as illegitimate as her two brothers, so Henry had the law abolished, returning Elizabeth to her status as princess. They could now safely marry and reunite the two opposing Houses.

There was, of course, an inherent problem with that move: striking down Troth Plight not only legitimized Elizabeth, but the Princes too, and gave them both a more direct claim to the throne than that of Henry. This gave him a clear motive to have them removed—if indeed they were still alive.

So there you have it: two suspects, both members of an extremely bloodthirsty and ambitious clan and both with plenty of opportunity and motive to commit the crime and seize the prize—the prize being:

“This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,” (King Richard II.II.i.40-41)

You be the judge!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peter James Quirk is an author, freelance writer, and outdoorsman who spends his winters skiing and snowboarding and his summers hiking, biking, and playing tennis. His novel Trail of Vengeance has a strong ski theme; indeed, the villain of the story is a disgraced ski instructor. Many of his stories, however, cover World War II and its aftermath. It is a fascinating if tragic period to explore, and the villains and heroes are so easy to find.