Some Tarot Spreads

Meaning comes from relationships between symbols in the mind. One important set of symbols is the context of the question itself. If someone asks about love, and you draw the Lovers, the card means something very different from what it means if someone asks about business success. In love, a partnership with emotional overtones is a good thing. In business, however, such a relationship could lead to problems.

Another kind of context used in most systems of divination is that of the spread or template. This template divides up the life of the querent analytically, so that the cards can take additional meaning from context.

The simplest spread is the single-card reading. In the single-card reading, all the context is provided by intuition. The card is only a spark. This means the single-card reading is a bit of an advanced exercise, but a good one. It forces you to lean on your intuition and to rely on the divinatory state of consciousness. There are several books that list various questions you might ask, and the meaning of a single card in response. This approach is a bit more mechanical than necessary, but it does illustrate the role of context.

The more cards we lay out, the more associational meaning we can intuit from their combinations. If we draw one card, the context exists only in our mind, because there are only 78 possible cards we might draw from a full tarot deck. If we draw two cards, the context exists not only in our mind, but between those two cards, and there are now 6,006 (78 x 77) possible combinations of cards we might draw, and if we draw three cards, we suddenly have a large number of possible combinations of symbols (456,456 of them, 78 x 77 x 76). This is a lot of potential context, now not only in the mind of the reader and querent, but on the table itself. It’s not always the case that the more combinations of symbols the better, and too much complexity can be confusing. Extremely large card spreads can paralyze the imaginations of inexperienced readers. For them, it’s often wise to start small. But within reason, the more patterns that become available, the easier it is to enter the state of consciousness that makes associational reasoning possible.

Specific Spreads for the Tarot

The simplest tarot spread is the one-card spread, but how much space can I take to describe drawing a single card?

A more useful spread for most questions, and the workhorse that gets about 90 percent of my questions answered, is the three-card spread.

1. Shuffle your cards according to your preferred ritual and draw three cards off the top, laying them from left to right on the table in front of you.

2. Look at the middle card. That’s the main theme. Fit it to your question: what answers does it imply?

3. Once you have a few broad strokes laid out, look to its left and right, to fine-tune what it says.

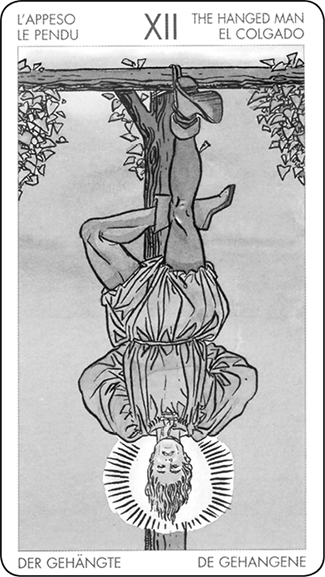

For example, you ask, “What do I need to know about my coworker Mary?” and you draw three cards at random from the major arcana and arrive at the Magician, the Tower, and the Hanged Man. The Tower is the central card, and Mary’s theme: she is undergoing some hard times, it seems. What sorts of hard times? Ones arising out of a lack of skills and talents. These hard times paralyze her: she’s unable to move. The cards change meaning if rearranged; if we put the Hanged Man in the center, we now have a woman undergoing an initiation which will gain her new skills, even as it tears away old edifices.

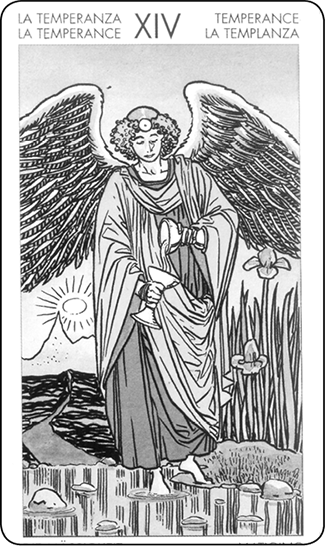

Let’s try another example. I ask the cards, “How can I quickly and successfully finish the book of poetry I’m working on?” I draw three cards—hold on, let me go get my deck—and end up with the Empress, the Hanged Man, and Temperance. The theme card is the Hanged Man, which counsels stillness. So that seems to indict the “quickly” part of my question: “You can’t do it both quickly and well,” it seems to say. The Empress reminds me that many of these poems are love poems and must be genuinely felt, not merely faked. They have to grow naturally out of real experience. Finally, Temperance is the card that Crowley renamed Art: here, it seems to suggest mixing and matching. It seems to suggest that perhaps some fragments and partially finished poems could be combined into new poems.

Nonce Spreads

The three-card method of reading can be detailed and efficient despite the low number of cards. As I said, most of the times I consult the tarot I use this method. I also sometimes create what I call nonce spreads: spreads I just make up as I need them. Say I want to know which of two choices would lead to better results. I’ll ask, “What will be the result if I do such-and-such?” and “What will be the result if I do this other thing?” I draw three cards for each choice and lay them out in front of me. I read each of them as a hypothetical story tracing out the likely results of making each decision. Alternately, I might label a particular set of triplets pros and another cons, and read them that way.

The method for doing this is not as intimidating as it might seem. You simply need to divide up your question into parts.

1. Begin by writing out your question, as explained in the previous chapter, in as much detail as you can.

2. Circle every noun and verb in the question you have laid out. Nouns, as you recall, are words that describe objects, including people. Verbs describe actions.

3. Lay out a card for every noun and verb that seems significant to you. You may also lay out clarifying cards where they seem appropriate.

4. If your question begins “how” you can lay out cards for “advice” and “warning,” as well. If it begins “why,” you can lay out cards for levels of cause—surface cause, deeper psychological cause—or effects, as seems appropriate. For “option” questions, I lay out separate cards for each option.

For example, if I ask, “How can I get that promotion at work?” I identify one verb—get—and three nouns: “I,” “Promotion,” and “work.” So I lay out four cards—one for my position, one for the action of getting the promotion, one for the promotion itself, and one for the work environment. I may also lay out some clarifying cards based on the type of question: a card for advice, what I should do; and a card for warning, what I should not do.

Procedures

With the major arcana alone, you’re limited in the sizes of your spreads somewhat. But even with only twenty-two cards, you can get some significant detail using a reading procedure rather than a spread. A procedure differs from a spread in that it doesn’t impose a layout or a set meaning to the card positions. It might also include several different ways of reading the cards in one throw.

I’ve created a simple procedure for the major arcana below, loosely based on the long and detailed Golden Dawn method of reading the cards. If you’re interested in the full method, it can be found online in several places, as well as in Israel Regardie’s Golden Dawn.17

1. Begin by shuffling your cards according to your usual ritual.

2. Ask a question about a particular situation, then pull off the top card and set it to the left-hand side. This card is the “one card” answer to your question, or the overall theme card.

3. Now deal the remainder of the cards into three rows of seven cards each. The top row is the past; the middle the present; and the bottom row is the future. Or you could rebrand the rows for some questions: let the top be the plot, the middle row the characters, and the bottom row the setting.

4. The first card in each row is that row’s theme card. Combine the theme card’s meaning with the overall theme card to get an overview.

5. Now it gets tricky. You won’t read every card; just the ones pointed to by the theme cards and subsequent relevant cards. Use the table below to count from the theme card to lead to another card, which you’ll also read, tying it to the question and the theme, as well as the meaning of the pack.

6. From that card, count to the next, and so on.

7. When you get to the end of the line, just keep counting from the beginning again, until you land on a card you’ve already read. Always count the first card as one (so if the top row’s theme card is the Fool, you’ll count it as one, the next card as two, and the card after it as three, which you’ll read). Perhaps you’ll read most of the cards in the stack; perhaps you’ll read only a couple. Either is fine; it just means more or less is going on.18

8. You probably won’t read every card, so what about the ones you don’t read? They’re not irrelevant: they offer some detail about the cards they are adjacent to. You can fine-tune meaning, and determine if a card is benevolent or malevolent, by the cards that flank it.

This is a difficult procedure to explain in the abstract, so let’s give a specific example. Once you see it play out, you’ll see how easy it is, and also how useful it can be. (And if you wish to read with the whole deck, you can modify this spread for the whole deck by counting the number of pips. Count aces as five. Queens, kings, and knights are four. Pages are seven. You may wish to extend the row to ten cards, if you do this.)

|

Count as Three |

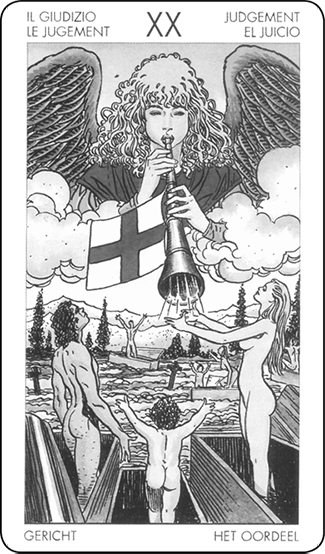

0–The Fool, XII–The Hanged Man, XX–Judgement |

|

Count as Seven |

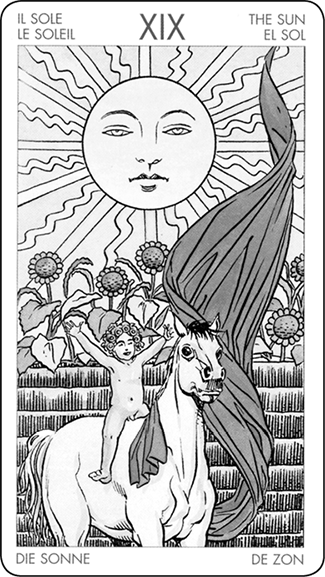

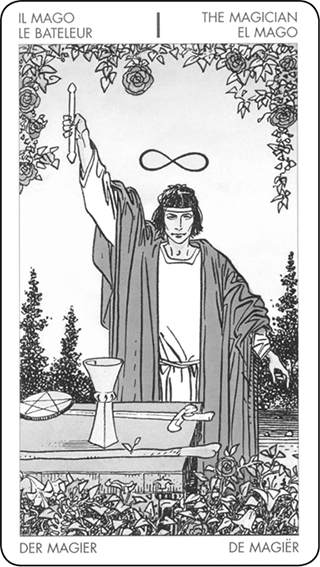

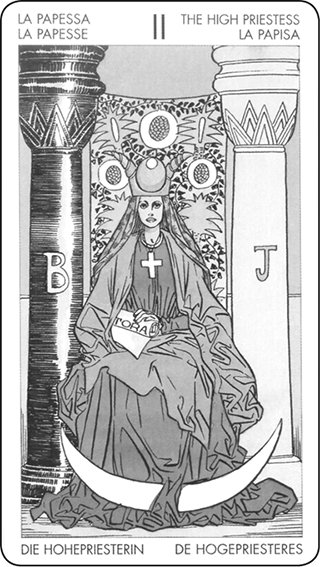

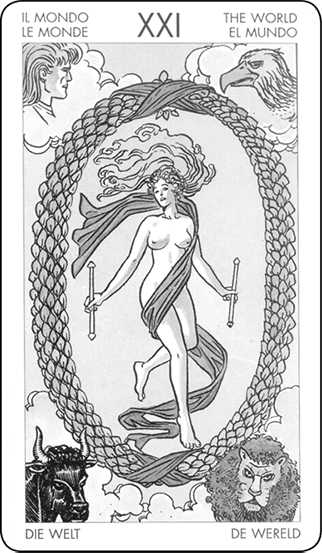

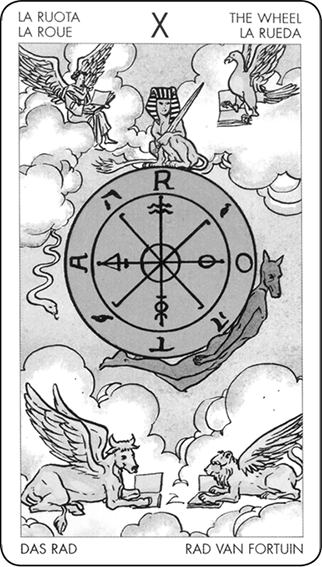

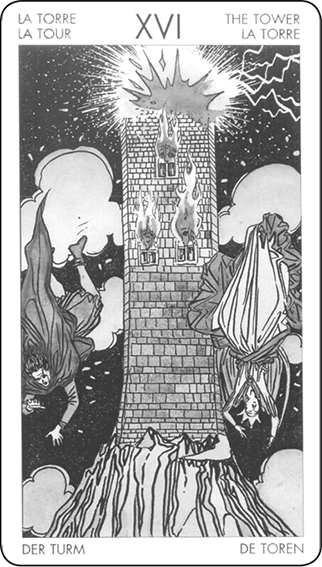

I–The Magician, II–The High Priestess, III–The Empress, X–The Wheel of Fortune, XVI–The Tower, XIX–The Sun, XXI–The World |

|

Count as Twelve |

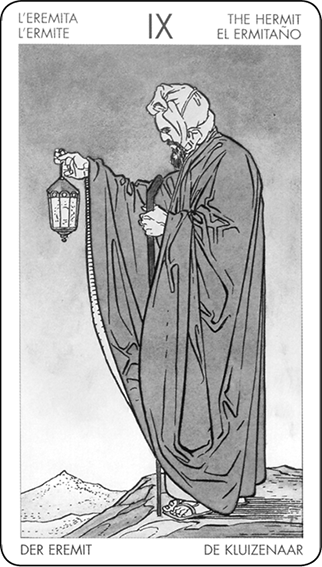

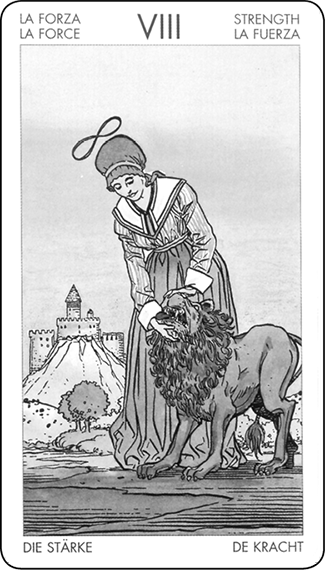

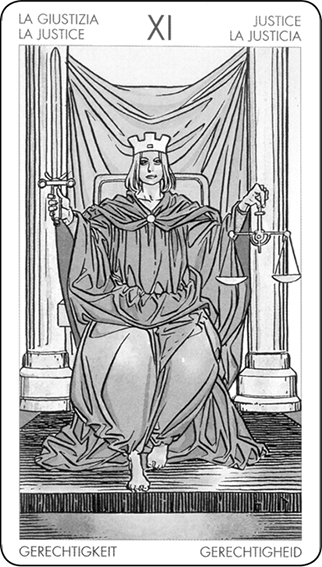

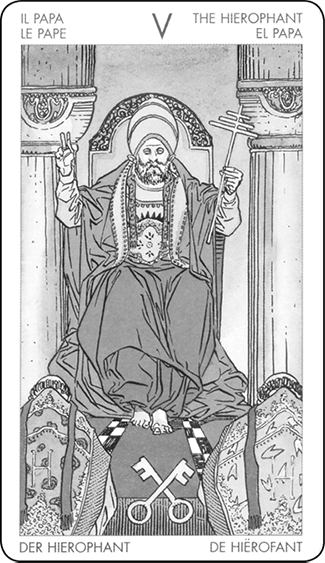

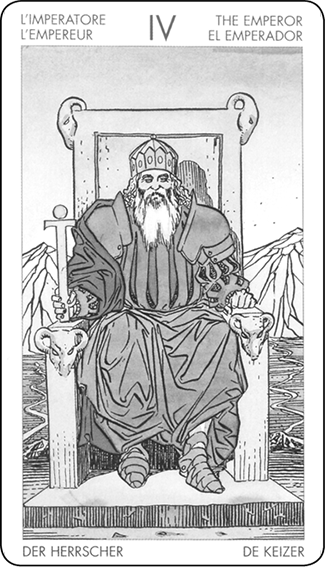

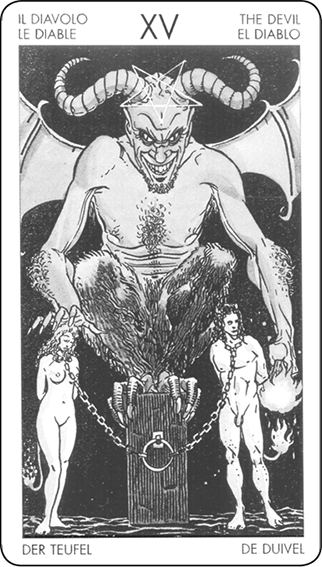

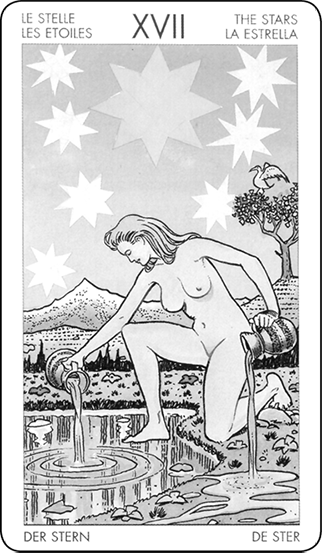

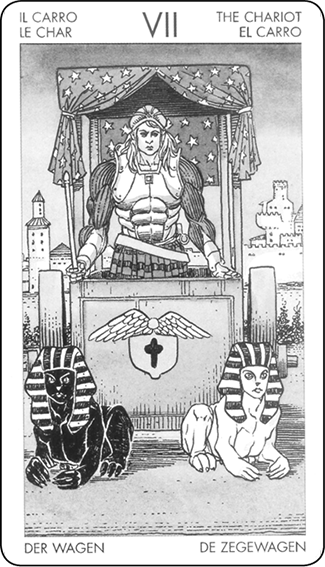

IV–The Emperor, V–The Hierophant, VI–The Lovers, VII–The Chariot, VIII–Strength, IX–The Hermit, XI–Justice, XIII–Death, XIV–Temperance, XV–The Devil, XVII–The Star, XVIII–The Moon |

For my example reading, let’s imagine I’ve just made an error in my investments that has lost me some money. I need to know how to proceed. So I shuffle the cards and ask, “What do I need to know about the past, present, and future of my financial situation?” I lay them out in the following tableau:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Justice as the overall theme card is reassuring to some degree. The loss isn’t large and can be made up, apparently, making me break even.

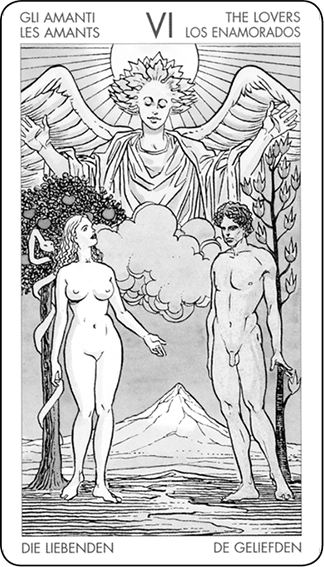

Some choices [Lovers] have proven foolish [Fool] but there’s a way out [Chariot] that will allow me to break even [Justice].

I would read the past line as follows.

|

The Lovers |

Some choices I have made … |

|

The Magician |

. . . involving education . . . |

|

Judgement |

. . . and a change in lifestyle … (viz., I was in college a very, very long time) |

|

The Hermit |

. . . and a career in teaching and writing … |

|

The Sun |

. . . have proven beneficial … |

|

Temperance |

. . . and wisely balanced. |

|

The Hermit, so since this is a repeat, we stop. |

Wow, that’s a lot of cards. I’ve had an eventful financial past, but since I had to be in college so long, I often wondered if the poverty and the loans would prove worth it. This tableau reminds me that, in fact, it has been. I’ve made good financial decisions in the past: I must not forget that just because one investment turned out unwise. This helps put it all into perspective.

In the present, my theme card is the Fool, which describes me fairly well, in both its negative and positive aspects.

|

The Fool |

Jumping in without double-checking … |

|

Death |

. . . has led to a loss due to confusion (the adjacent Moon card indicates this). |

|

The Devil |

There’s no way out of this mistake … |

|

The Empress |

. . . but overall, there’s still growth. Don’t panic (from the adjacent Hierophant). |

|

Death, again, so since that’s a repeat, we stop. |

And that’s pretty accurate. A mistake led to a loss of funds that wasn’t reversible. But it was a small amount of money, relative to my other investments. And so maybe, through growth, there’s a way to recoup that money. Growth of money is interest. Hm.

In the future, my theme card is the Chariot. That means overcoming difficulties, but it also reminds me of my car, on which I owe a certain sum.

|

The Chariot |

My car … |

|

The World |

. . . can be brought full circle … |

|

The Star |

. . . and offer some freedom and hope. |

|

The Chariot, which is a repeat, so we stop. |

That seems a bit opaque, unless the Chariot doesn’t mean my car. But my intuition is that it does. What does the sense of completion offered by the World indicate in the financial world? Paying off a loan, perhaps. The Wheel of Fortune, adjacent to the World, reminds me of the principle of cumulative interest. And the Hanged Man is adjacent to the Star: that’s one bill I can hang to dry, as it were. I look at what I owe on my car, calculate the amortization, and realize that if I used some of my savings to pay off my car, I would save almost as much money in interest as I lost previously. After a few more calculations, I get online and do just that. Now I’ve not only avoided that interest, I’ve given myself an effective raise every month.

Wow, ain’t divination dandy.

Okay, most people probably don’t need divination to make financial decisions, and the notion of using my savings to pay off my car early had occurred to me before. But the divination pointed out that it was a good idea and that I should pursue it. And best of all, it got me off my butt.

By the way, some time later I received a check from the financing company informing me of an error in my favor. I had overpaid and they were sending me a reimbursement. It was $50 shy of the original lost amount.

Let’s try another one, this time rethinking the three levels as plot, characters, and setting of a particular “story.” Let’s imagine we have a querent who comes to us asking about an upcoming business trip. He’s to present some fairly iconoclastic information to a group of experts, and he is a bit nervous that they might be a touch hostile.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Card XIII, Death, is the theme card. This conference represents a change. If we were reading with the minor arcana, we might say “a big change,” but instead this could just be something new: perhaps even just the first time the querent has been to this particular city—which it is.

Still using the counting method described above, we read the first line as “plot.” The plot tells us that the querent’s skills (the Magician) will be tested (the Tower) but will overcome (the Chariot) constraints (the Devil).

“What kind of restraints?” our querent asks.

We look to the cards flanking the Devil, as well as those below it. “Your ideas will be weighed (Justice) against common knowledge (the World), and many people will simply lack the insight to understand them (the Fool).”

The characters in this little drama are revealed in the middle line. Still counting, we have here dreamy (the Moon) and idealistic (the Star) people, who are nevertheless capable, intelligent (Strength), and bright (the Sun).

The setting is the Hanged Man, indicating that there won’t be much traveling around once there. This card could presage a trip that involves a lot of time just hanging around the hotel room. “I kind of loathe the social parts of these things. Too much drinking, too much posturing,” the querent says.

“Well, good news: you won’t be doing much drinking or be around people who are (Temperance). But there will be an atmosphere of high expectation and traditions (the Hierophant), especially of your superiors (the Emperor is adjacent to the Hierophant); this is an environment that calls for wisdom (the High Priestess).” Of course, as it is an academic conference, this rings true.

One point of these examples is that the meaning of the cards exists only in relationship, either to the situation or to each other. In questions about a trip, the Hanged Man might indicate delays or “hanging out,” while in questions about spirituality, it might indicate a personal sacrifice. Similarly, next to the Hierophant, the Hanged Man will take on qualities of sacrifice and initiation; next to the Lovers, it’ll be a deferred choice; next to the Emperor, it might indicate “being hung out to dry” by the powers that be.

A similar relationship between the cards and their context exists in the Lenormand, and most Lenormand spreads are designed to capitalize on the power of these combinations. Many spreads are somewhat similar to the tarot tableaux I describe above, which is why I wanted to introduce it to those unfamiliar with this way of reading the tarot. In the next chapter, we’ll take a look at some traditional and newer ways of reading the Lenormand.

17. Israel Regardie, The Golden Dawn (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1989).

18. Mathematically astute readers will notice that counting twelve is equivalent, in a row of seven, of counting five. And counting seven will always land you on the previous card. However, since this same method can be used with other, larger tableaux, I’m offering the original numbers in the table. Feel free to take shortcuts.