Some Lenormand Spreads

Your first impulse in picking up a Lenormand deck might be to read it just like the tarot, assigning positions and laying out cards. That’s not necessarily a bad instinct. Any perusal of the few books in English on Lenormand will give you a few such spreads. In that sense, we can say that we read the Lenormand the same way we read the tarot.

But there are some differences, and they have to do with the structure of the symbols. As we’ve seen, the Lenormand symbols represent day-to-day occurrences, especially in the life of an eighteenth-century bourgeois woman, with a pronounced Romantic bent. Our experiences and concerns are closer to the bourgeois of the eighteenth century than they are to the monks of the Middle Ages or the scholars of the eighteenth century, which might be one reason that the Lenormand feels so “practical.”

Let’s explore some of the differences in the structure of the Lenormand with an eye toward how they will help us develop Lenormand spreads, including the Book of Life and Sylvie Steinbach’s No Layout spread.

Situation Cards

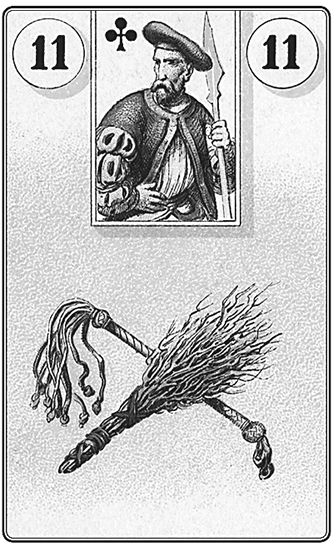

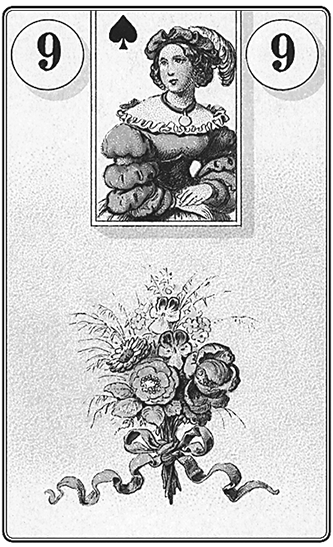

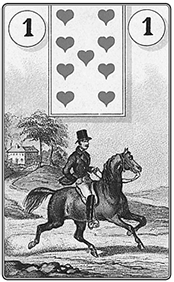

Situation cards are sometimes called “signifiers,” and there are a lot more of them in the Lenormand than in the tarot. Nearly any card could become a signifier for a question, but in practice there are a few cards that most readers use, again and again.

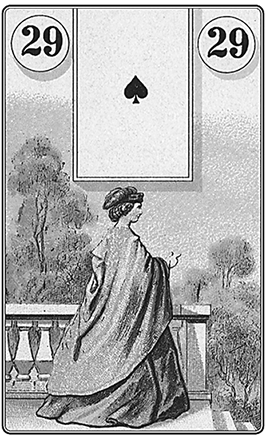

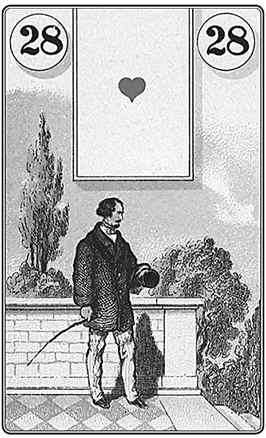

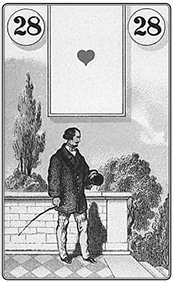

Two cards, 28–Gentleman and 29–Lady, are the most important signifiers. They signify a man and his wife, or a woman and her husband. If your querent is a man, he is 28–Gentleman and his wife or girlfriend is 29–Lady. If a woman, 29–Lady is the signifier, and 28–Gentleman is her husband or boyfriend. Everything here breaks down nicely by gender.

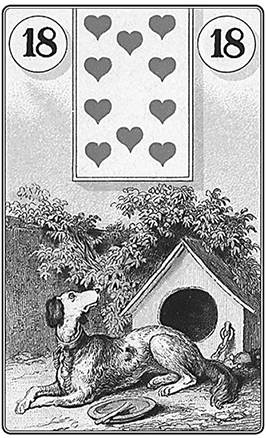

If you happen to be gay, or reading for a gay querent, then you need a third card, which is 18–Dog. That might seem insulting, but the Dog represents a close friend of either gender, and so is an all-purpose card for someone you know well. You could also—and perhaps more often will—use this card to indicate a friend, romantically or not. I’ve also noticed that, at least for me, the card of opposite gender sometimes just means “partner,” regardless of sex or gender.

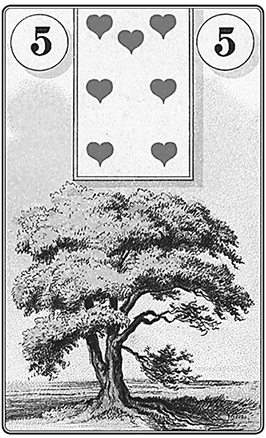

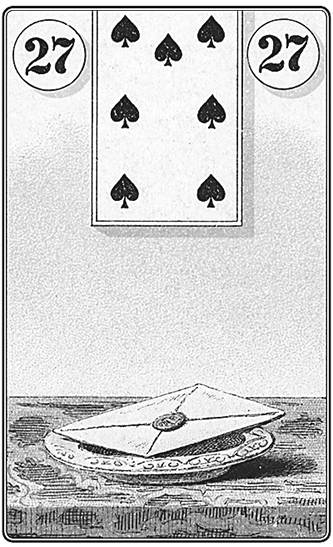

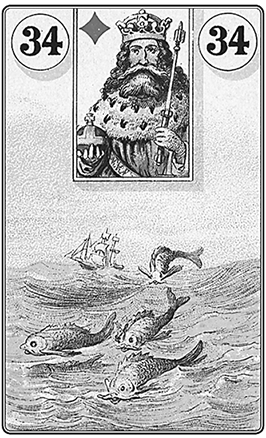

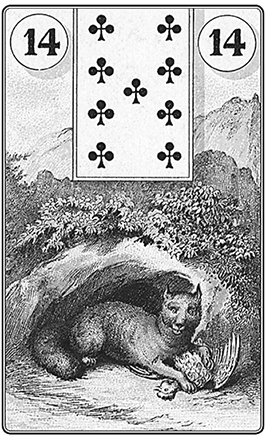

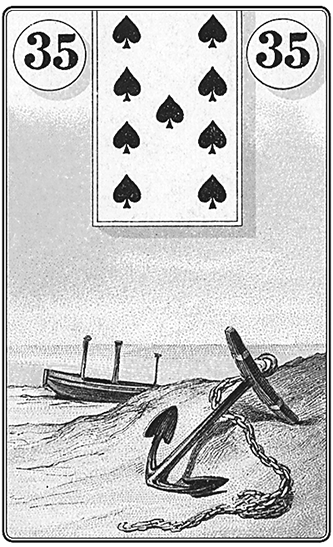

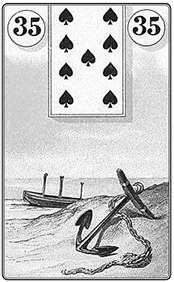

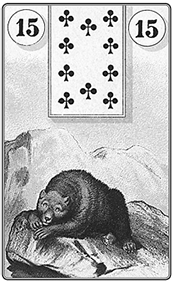

Cards can also represent issues. For example, if you want to know about someone’s health, 5–Tree will tell you what you wish to know (need I mention the importance of going to a doctor, as well as consulting the cards, and not using the cards as substitutes for medical advice from a qualified professional? If so, consider it mentioned). If your querent is curious about money, you might use 34–Fish or 15–Bear, with 34–Fish representing independent wealth and investments, while 15–Bear indicates individual cash flow and personal wealth. Stock dividends are 34–Fish, while your paycheck from work is 15–Bear. And if there’s a question about work, some traditional Lenormand readers would have you use 35–Anchor, while many American Lenormand readers (including me) prefer 14–Fox as a signifier of one’s job.

In theory, any Lenormand card can represent the issue with which it is connected. A question about whether or not a letter will arrive, a book will be published, or for that matter a tower be built could all easily be associated with a card. In practice, a few cards come up again and again. For common signifiers, see the table below, which offers suggestions for possible signifiers.

Table of Possible Signifiers

|

Question |

Possible Signifier |

|

Money |

15–Bear |

|

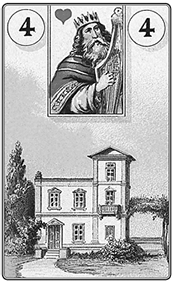

Family; real estate |

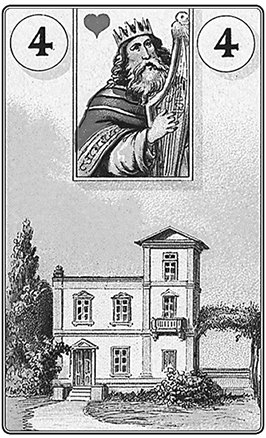

4–House |

|

Love |

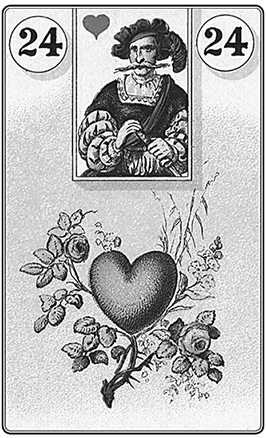

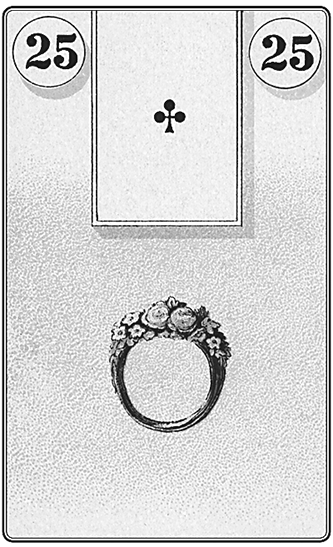

24–Heart |

|

Partnership; contracts |

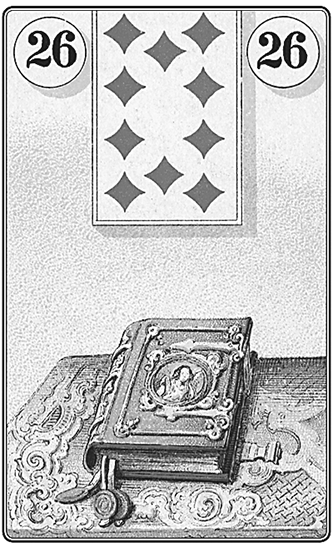

25–Ring |

|

A friend or lover |

29–Lady; |

|

Work |

14–Fox |

|

Health |

5–Tree |

|

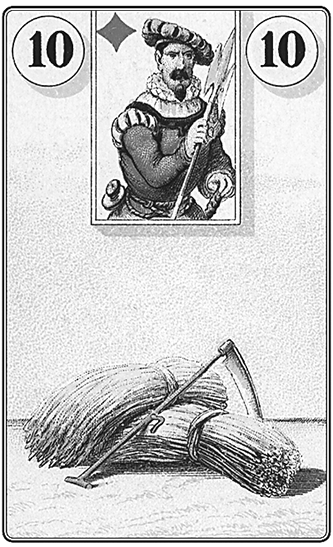

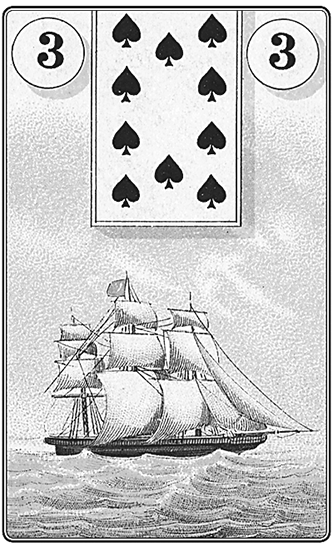

A trip |

3–Ship |

You can choose to make a card the signifier in a given reading by deliberately associating it with the issue it is to signify. In most readings, you’ll at least want to do this with 28–Gentleman or 29–Lady, to associate it with the querent.

You can create this association by pulling the card and holding it, while looking at the querent. Mentally imagine the querent’s features transferring to the card, and when you feel this process is complete, reshuffle. If the querent isn’t present, you can call the card by the querent’s name: “You are so and so” a few times, then shuffle it back into the deck. If you’re reading for yourself, you might find it useful to imagine yourself in the card, looking through the eyes of the person pictured. I might visualize myself striding in the garden, wearing a top hat and reading a letter (I look excellent in a top hat). Then add the card back to the deck and reshuffle.

For signifiers of issues, you need to imagine the object or idea associated with the card. The process is much the same: if I want to know what’ll happen with my family as a whole, I imagine my house and household taking the place of the house in 4–House. If I’m asking about work, I might imagine the fox in 14–Fox sitting under my desk instead of under a bush.

This can be done quickly, and once you become familiar with the cards, you won’t need to take them from the deck to do it: you can just visualize them from memory.

Book of Life or Grand Tableau

Once you link one or more cards with an issue, you can use the traditional spread called the Book of Life, also known as the Grand Tableau, to answer a number of questions at once. This Book of Life spread actually gives a snapshot of the month or so to come, in my experience, although you can fine-tune it by asking it to give a longer or shorter period of time. You could even do a Book of Life spread for the next day or so, although that would probably be so much more detail than you would ever need.

There are as many ways to read the Book of Life as there are Lenormand readers. Different readers even have different ways of laying out the tableau. The most common way I see is to lay out four rows of eight, with a row of four below them and centered. But Juan García Ferrer suggests laying the cards out in four rows of nine.19 He offers an extremely complete and complex description of all of the ways of reading the cards in the Book of Life spread.

In general, techniques for reading these cards can be broken into two rough categories: common techniques and uncommon techniques. Readers differ on how they do everything from laying out the cards to determining the lines of present and future. But they do agree on some basic principles. The system I lay out here is my own homebrew, built out of those common techniques and what works for me. If you’re interested in learning some other, more advanced techniques, you can do a lot worse than Ferrer’s El Método Lenormand, although as far as I know there is not an English edition. You will eventually need to invent your own method, just as I have, and it will appear as strange to other Lenormand readers as this description might appear to those who learned a different tradition. Just as we each develop a unique way of speaking, we each develop a unique way of interacting with the Lenormand’s symbols.

Step 1. Before laying out the cards, identify one or more signifiers through the process outlined above.

Step 2. Then shuffle the cards according to your preferred ritual. At this point, authors disagree. Some deal from the bottom of the deck, some the top; some fan the cards out. Do what you prefer and whatever feels most natural. I just deal from the top of the deck, as if laying out a game of solitaire.

Step 3. Lay out the cards in four rows of eight with a row of four centered below.

Step 4. Read the first card. This is a general theme of the reading. Imagine that its meaning is a sort of diffuse light over which everything else can be seen. Don’t make the overstatement mistake. If it’s card 25–Ring, don’t jump to the conclusion that the querent will be married. Instead, realize that promises, contracts, and groups of people might all be important during the time of the reading.

Step 5. Find the querent’s signifier. If the signifier is to the far right, that means the future might be somewhat unclear. If to the far left, then the past might be unclear, or this might be the start of a brand-new phase of life, one without much of a past. If near the top, the querent might be just coasting through life during this period; if at the bottom, the querent may be overwhelmed with plans and ideas.

Step 6. Read the cards to the right, top, left, and bottom of the querent. These cards describe the querent’s current condition.

Step 7. Read the cards above the querent in a line going up. These reflect things just coming into being, plans and ideas.

Step 8. Read the cards below the querent in a line going down. These reflect things the querent is overcoming or repressing.

Step 9. Read the cards in front of the querent stretching to the right (or, in some systems, in the direction the figure in the card is facing—whichever works for you). These reflect the possible futures.

Step 10. Read the cards behind the querent, stretching to the left. These reflect the past.

Step 11. Read the diagonals.

The upward-right diagonal reflects plans about the future.

The downward-right diagonal reflects unknown, unconscious, or unrecognized future possibilities.

The diagonal upward-left reflects past ideas and plans.

The diagonal downward-left reflects obstacles overcome or memories forgotten.

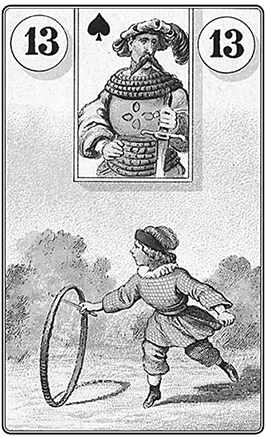

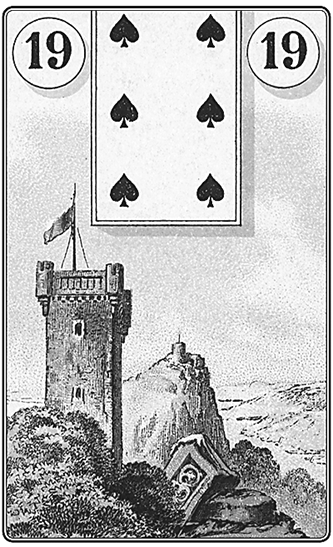

When reading the lines, it’s important to “chunk” cards into combinations of two or three, in order to create a smooth narrative. There are pages and pages of combinations listed in various books, but really you need to construct them yourself. This issue of combinations gets into the grammar of the symbols of these cards, which I’ll go into later in greater depth, but in general ask yourself, “What cards seem to go together?” The first card is the topic, the next card or two the comment. So if 25–Ring comes up, you might say the topic is promises. What kind of promises? If 18–Dog follows it, friendly ones. That naturally leads to “what about?” which should be answered by the next card: say it’s 13–Child, then perhaps they’re promises to babysit or watch someone’s children. But what if it’s 19–Tower? Ring followed by Tower would mean legal promises, but what if the Dog’s in between? Then perhaps it means a friendly promise from someone in authority, maybe a lawyer, who is a sort of legal friend, or perhaps you should start a new combination with Tower asking, “Okay, a kind of power or authority—what kind?” and look to the next card. If it’s 6–Clouds, it’s a confusing kind. So you could read 25–Ring, 18–Dog, 19–Tower, and 6–Clouds as a promise from a friend involving a confusing authority: oh, it’s a friend’s promise to help you with your taxes! Over all, rely on your personal intuition, keeping in mind the role of the individual imagination in the philosophy of this deck’s designers.

This procedure constitutes the basic method of gaining the general gist. There are several ways to proceed from here.

After reading the personal signifier, you may wish to find other signifiers. For example, the querent might say, “How will my job go this month?” You could look, depending on your system, for 14–Fox or 35–Anchor to answer that question. I prefer using 14–Fox for work, so I would use that. Then read it just like the personal signifier above. If one of the lines from a signifier intersects with the personal signifier card, that signifier’s influence will be felt. Distance also matters: those things more distant from the signifier are less, well, significant. Some traditional readers read signifiers close to the personal signifier as more negative than those away: for example, 5–Tree near a signifier might indicate, some traditions say, a health problem, while far away it would mean a clean bill of health. I don’t like that method at all. 5–Tree near the signifier just means the signifier is thinking about or will be involved in his or her health. It could just as easily, depending on surrounding cards, indicate a healthier lifestyle. Although in some cases, such as 15–Bear, which often represents money and cash flow, the distance between the card and the signifier is relevant. If 15–Bear is far away from the signifier, it might mean that cash flow is distant—either the querent isn’t concerned about it, or someone else handles it, or there is none. Other cards around 15–Bear will explain which. So distance does matter, but it’s not always knee-jerk negative or positive. It depends on logic, common sense, and intuition.

Once you finish hunting down signifiers and so forth, you may be stuck on a few cards. Perhaps you’re not sure and want some more insight on individual signifiers. Fortunately, a more advanced technique, the technique of houses, lets you do that.

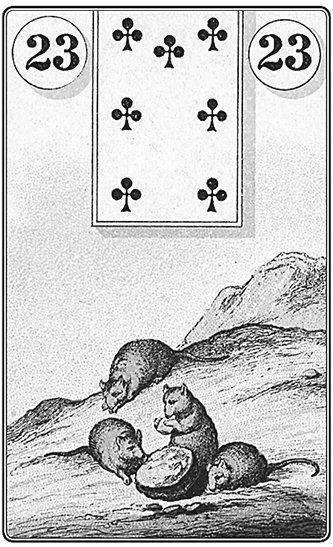

Each of the positions, starting from one to thirty-six, has an “invisible” card on it, associated with the number of its position. So, for example, if the signifier 28–Gentleman lands on the fifteenth place, you can imagine a ghost card of 15–Bear with it. These invisible cards, the houses, offer an “in other words” reading. If 28–Gentleman lands on 15–Bear, I might say, “You’ve got some cash flow issues.” Whether good or bad should be readable from the other cards. I can also use this to help describe a person: if 18–Dog lands on the twenty-third place, I can say, “This is your friend, the kind of squirrelly, mousy one who’s always mooching off of you,” because 18–Dog takes on some of the characteristics of 23–Mouse from its location.

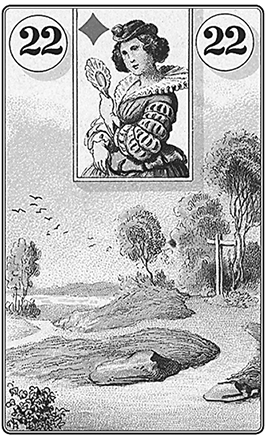

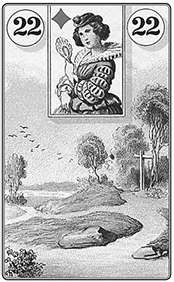

The technique of houses is useful in identifying people; however, you can get even more detail if you look at the cards on the corners of any card you suspect of representing a person. So if you’re reading the future, and you have the friend who’s going to help you with your taxes, a querent might say, “Wait, which friend?” You can look, first, at the house, but you can also check out the corner cards of 18–Dog to refine the meaning. Say you have 1–Rider, 13–Child, 29–Lady, and 22–Crossroad. From this, I know that the person is athletic, kind of childish—or maybe a new friend who has just come into the querent’s life—feminine, and perhaps a bit indecisive. Some cards lend themselves better to description than others; don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know what that card means there” if something doesn’t fit.

The technique of houses, by the way, explains why we read the first card as a general indicator of the spread. The first house is 1–Rider, which represents a visitor or a message. And what’s the most current, relevant message occurring in this particular moment? The one the reader is offering the querent, presumably.

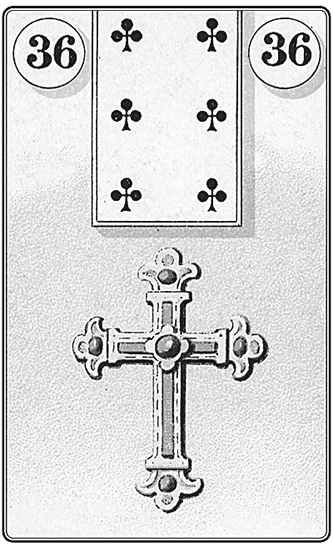

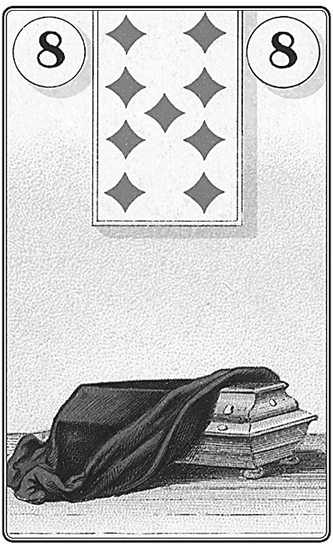

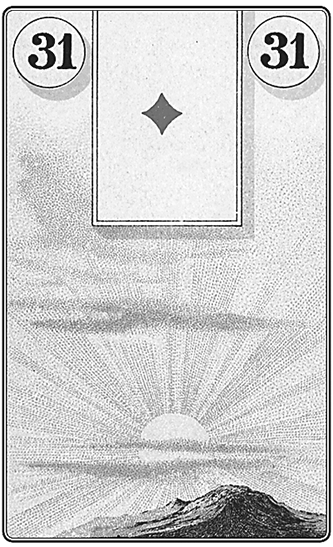

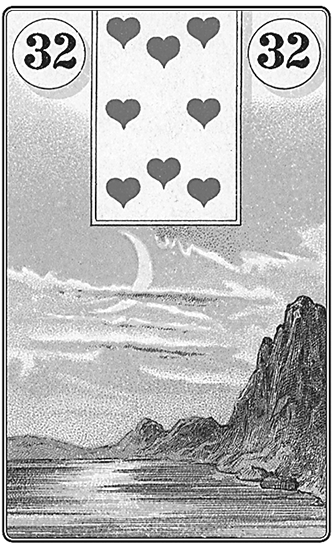

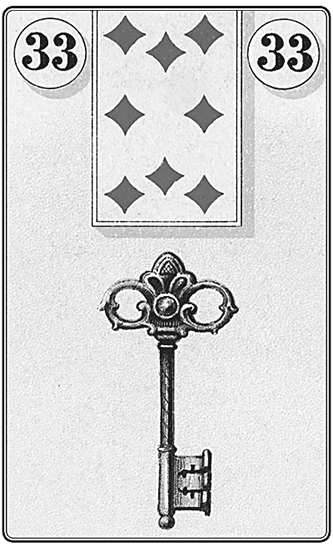

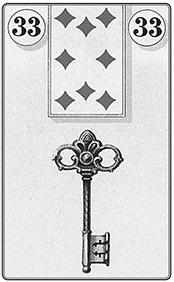

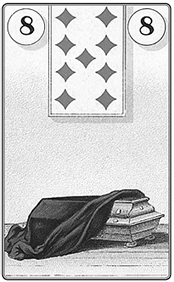

All six cards in the corners of the tableau, because of the houses they occupy, indicate general trends about the reading. It can be important to read these cards; they can cast a light on the rest of the spread. The first card, as we said, is the general trend of the reading: you can think of it as what’s coming in. The last card of the first line, card number 8, is what’s ending or going out, because it is associated with 8–Coffin, which represents endings. The card in the left-hand bottom corner, card number 25, indicates the role of partners or others around the person, because 25–Ring represents the promises of others. The card at the end of that last long line, card number 32, tells us the emotional state of the querent, because that is one of the roles of 32–Moon. The next card, 33, tells us the nature of any recent key events, as it is associated with 33–Key. It might identify those events, or just tell us about them. Finally, the last card, 36, is often the place of worries or fears about the future, or spiritual matters if relevant to the querent and question, because its house is 36–Cross.

Following is an actual example I did for a stranger online, which isn’t optimal, of course, as I prefer face-to-face, where the querent can offer context and answer questions. But this example will illustrate a few important points, as well as how a reader can make a preconception that causes him (me, that is) to miss something important.

A querent comes asking for a reading. She says she prefers to get a general forecast, and only then ask questions. While it’s usually nice if a querent comes with questions, you can really go out on a limb this way and be brave. I’ll give my actual reading, mistakes and all, so you can see how a reading develops and how a good reading involves some give and take with the querent. Again, this isn’t cold reading: when I’m wrong, I admit it.

I lay out the tableau as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

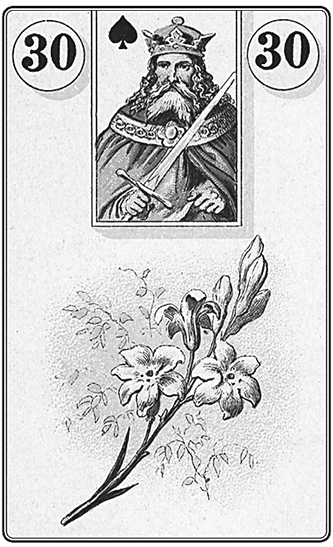

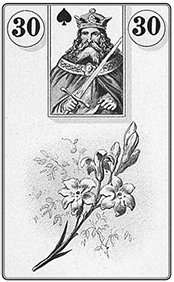

30–Lily is a nice card to start with: it tells me that everything will work out fine.

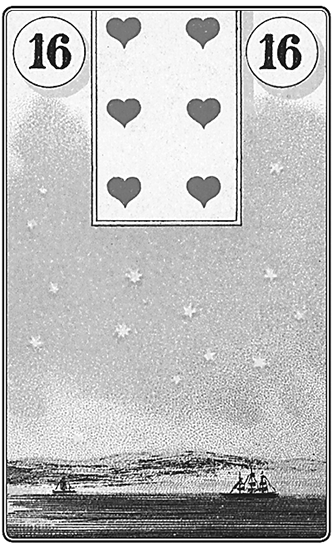

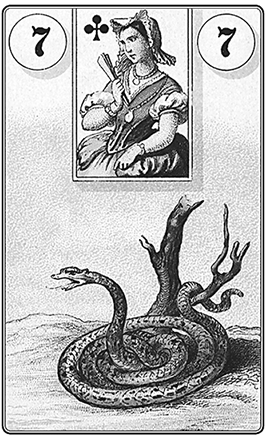

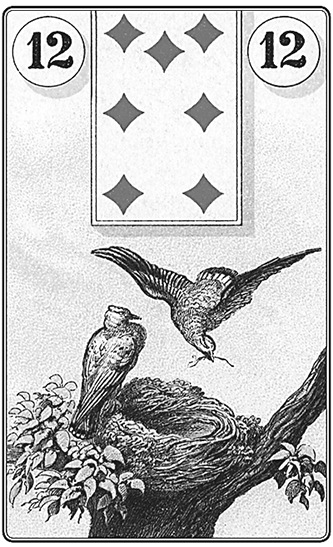

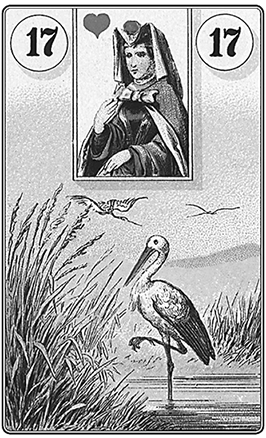

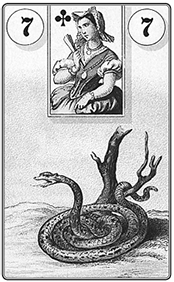

I find the signifier, 29–Lady. I look first to her past, which is long. She’s had a life-changing event recently (17–Stork). What kind of event? A conversation (12–Birds) about feelings and dreams (32–Moon). She also had a bit of happiness involving her job: a dream job, as it were. In her future is a man (28–Gentleman) and a child (13–Child) or perhaps a childish man, or a new start with a man. Above her, it seems she trying to find some beautiful words (9–Flowers, 27–Letter). Below her, she has put off making a choice (22–Crossroad) about her lifestyle (35–Anchor). She dreams of being adventurous in love (24–Heart, 34–Fish), and has perhaps put off school (26–Book) for this man. In the past, she’s been ill (5–Tree, 7–Snake). I suspect, because of 15–Bear, this illness may have involved food in some way, and 16–Star means it might be psychological. She may also have taken an important trip recently (3–Ship, 33–Key).

Let’s look at this man. He has a mountain on his heart: he has a hard time expressing his emotions. He’s also suppressing secrets (26–Book). In the past, his path has been cloudy: he has had a hard time making an important decision. But let’s look at his corners: 18–Dog indicates that he’s known to this woman already, and 9–Flowers tells me that he’s attractive. 22–Crossroad tells me that he keeps his options open, but 25–Ring tells me he might be willing to commit. And 25–Ring is also in his future, in the deferred or avoided future. But I’m going out on a limb: he’s proposed and they’re getting married. As you’ll see, this limb will crack under my weight later, because I did not attend to the place of 25–Ring closely enough.

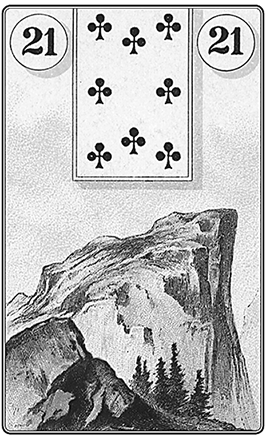

It’s always worthwhile to take a look at the place of 15–Bear in the tableau, as it can indicate ready cash. It’s rather far from the Lady card, which usually means some cash flow problems. 36–Cross speaks of worries in the past, which have turned out just fine (30–Lily). Below the Bear is 8–Coffin and 32–Moon: the worries about money have led to feeling as if all dreams have to be boxed up and set away. There’s a dread of painful news (1–Rider, 10–Scythe). In the future, though, we see reliance on family (5–Tree) and hope (16–Star), but the bills (27–Letters) pile up (21–Mountains). Eventually, though, there’s a good omen: 34–Fish speaks of financial independence.

At this point, I ask the querent what she thinks. First, she tells me I’ve got it all wrong: for one thing, she’s gay. This tendency toward heterosexism and sexism is a drawback of the Lenormand. I tend to read the Gentleman and Lady cards as more general “people” cards, often of any gender, but here I jumped to a conclusion you’d think I would have avoided, being gay myself. And, she says, my limb is cracking, because in fact she has recently proposed and her partner has said no and moved out! Obviously, in retrospect, she “turns down” the ring, because 25–Ring is in the lower diagonal. She’s not sure, she says, how she’ll survive on just her income, which is moderate. She may have to leave her house (4–House, 8-Coffin).

If I had read the corners more closely, I might have realized a lot of this. What’s ending is her independence (34–Fish). Although I took that to mean that she would be getting married, it was much more financially literal than I suspected. Card 19–Tower can indicate isolation, which is in the place of her partner, and what’s affecting her emotions is 25–Ring, the proposal. The key event is clear: 10–Scythe, which traditionally has almost always meant a breakup. And finally, her fears are represented by 35–Anchor: she fears that she will not be able to maintain her lifestyle.

Yet I stand by this: Lily is in the first place, and I still see the two of them together, in a new (13–Child) relationship (or, perhaps, literally with a child!). It’s clear now to me that the beautiful thing she wishes to craft out of words is a way of winning her partner back. Will it work? It’s hard to see for sure, but the partner is still in the querent’s future, at least as a friend, perhaps as more. They do share fond emotions (24–Heart).

Fortunately, other factors, including the fact that she does enjoy her job, despite its moderate income and her past dealing with a food-related disorder, were accurate and helpful insights for the querent. The error on my part was in jumping to conclusions and reading into the tableau what I wanted to see. This is an instructive error, because it’s very easy to fall into it, particularly when the querent is absent and you want to be nice.

This reading illustrates one of the drawbacks of the Grand Tableau or Book of Life spread: it can make fiddly distinctions of great importance. The place where the Ring lands around the Gentleman card affects its meaning. Yet if 18–Dog had landed there, would that have made him (in this case, I suppose, her) less friendly? No, it’s a matter of context, and it’s difficult to define hard and fast rules.

And the querent’s role in determining that context is important. If I say, “This is a man who … ” and the querent says, “Are you sure it’s not a woman?” it may well be. As a reader, you need to rely not just on the cards and their meanings, but the context provided by the querent and no less importantly your own intuition.

The other drawback of the Book of Life is that it takes a long time. Sometimes, you have a simple question and want to know the answer immediately. There are two other spreads you can use when you wish to answer this kind of question, which I imagine will be the most common spreads used by most readers. I use one of these two methods more often than I use the Grand Tableau. Both of them, however, rely on the same skills as the Book of Life: perception of patterns, parsing and reading a line of cards, and understanding cards by their positions.

Sylvie Steinbach describes a unique system she calls the “no layout” spread.20 I do not wish to step on her toes: my brief explanation cannot substitute for reading her book. In essence, she charges one or more signifiers, then draws cards until that signifier appears. She reads two or three cards on either side of that signifier to get information about the near past and future of the querent. She explains that one can charge multiple signifiers in a single reading: 29–Lady, for the querent; 4–House for her family; 15–Bear for her cash flow situation. This method is, if you think about it, essentially an abbreviated Book of Life: instead of laying out the whole tableau, one just lays out the near future and past of the relevant signifiers.

This signifier becomes the theme upon which the other cards act as elaboration. This process is similar to that of the tarot, in which we say, “This card, the Knight of Wands, represents you,” or “This place is the place of the future.” Note that in the tarot, we can charge a card as signifier, or we can charge a location in the spread with meaning. Both methods are similar. We simply project that meaning, either upon the card’s image in our imagination, or upon the location on the table where we intend to set the card. Similarly, we can charge locations on the table , just as we can charge cards in the Lenormand with meaning.

A similar spread to the No Layout spread, and one that I’ll explain in greater depth, does much the same. But in this case, you do not charge a signifier but a location on the table. You still charge it as a card, however. So, for example, you might decide to charge a location with the querent’s identity: 28–Gentleman, let’s say. Now I lay five cards, with the middle card on the place I have charged as 28–Gentleman. Now we read that card as if it is in combination with the querent: it expresses his current state. The cards on either side are read as past and future trends.

We can again charge multiple signifiers and do what I’ll call the Petit Tableau. The Petit Tableau can answer a more specific question than the Grand Tableau and takes less time. Essentially, we charge two locations on the table: one for the querent, by visualizing the appropriate cards (usually 28–Gentleman or 29–Lady) projected or visualized in that place; and one for the question, by projecting or visualizing the appropriate signifier card on the place below it. For example, if the querent is asking about money, we might project 15–Bear. If about love, 24–Heart. If about partnership, 25–Ring.

These charged locations then become the “houses” of those concerns. We can do any number of these; but I recommend starting with just two at a time, one house for the querent and one for the question.

Now, lay out five cards on each row, so that the middle card lands on the charged house. In the horizontal rows, read the cards in front as future; those behind as past. So you’ll have the theme cards, landing on the houses, related to the cards those houses are charged to. You’ll also have the future of the querent, the past of the querent, the future of the question, and the past of the question. You can also read how these trends interact by looking at the combinations created by the cards that land above each other in the spread.

Let me give you a quick example. Imagine that a querent comes to you asking about his job. How are things going at work? What will happen in the near future? The querent is a man, so we charge for 28–Gentleman, and work is the Fox, so we charge for 14–Fox (or maybe we’d prefer charging for 35–Anchor if we’re using European traditional associations). I lay out the cards with the theme card first, then the other four cards on either side in an alternating pattern, like this:

|

4 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

|

9 |

7 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

Doing so, after shuffling thoroughly and performing our preferred starting ritual, we end up with:

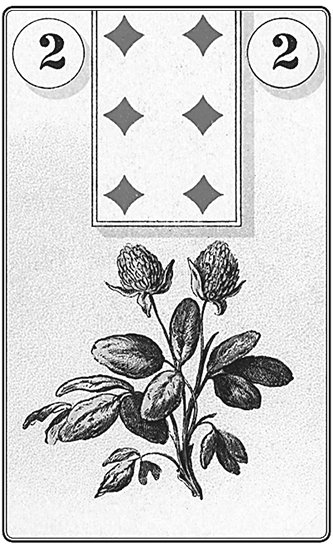

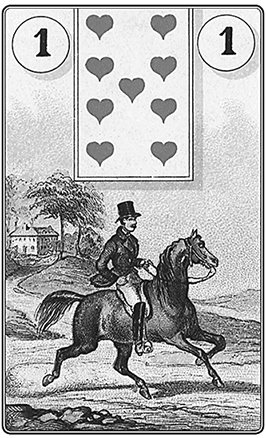

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now, we read starting with the middle card of the top row, charged with signifier. This is saying, “You’re a kind of messenger.” It could also mean “you’re on horseback, moving forward.” That’s good news. To the right we have the Anchor: the message you’re bringing is one of stability in the face of complexity and deception (7–Snake). So your role at work is to cut through the BS. In the past, there was a big decision (33–Key, 22–Crossroad), and you chose the best option. (Key is almost always a good card—I only read it as a disastrously bad event if the other cards are slapping me to do so.)

Now, as to the job: this is your dream job (30–Lily). You’re content here, and have accomplished a goal. 4–House might mean the coworkers are like a family. (“Actually, I just bought a house,” the querent says. “And I was concerned that I might not be able to keep it if something happened at work.”) Well, not to worry! Because there you are: the rider has come home at the end of the first row.

8–Coffin sometimes means endings, but really it’s about transformations, much like card XIII–Death in the tarot. Here we have transformation and 15–Bear, often a card of cash flow. Now, this might mean “cash flow comes to an end” if it were around another ending card, like Scythe. But it’s not: instead, it means “boxes of money.” In other words, a transformation in your financial situation. (“This current job more than doubled my current salary,” the querent says. “But I still don’t know if I have enough money for necessities.”)

15–Bear means “cash flow.” 30–Lily can mean “satisfied, enough.” So we can tell the querent that he needn’t worry: he’s got enough. There might be lean times and fat times, but overall he’s got what he needs here.

Now, we can read from top to bottom; unlike the horizontal rows, these are not necessarily situated in time. I tend to read them as comments on the present or predictions about the future, depending on intuition or the querent’s response. We start in the middle and read 1–Rider with 30–Lily. “Good news is coming: a major project is nearly done.” 35–Anchor, 4–House: “You’ve got a stable and long-term position.” 22–Crossroad, 15–Bear: “Lots of options for making money; work isn’t your only income stream.” 33–Key, 8–Coffin: “Big changes coming, although not a job loss because of 35–Anchor. Instead, you might find yourself moving up, changing titles.” 7–Snake, 28–Gentleman: “You’re a bit devious; that can serve you well, or it can serve you badly. But be aware that you don’t want a reputation for dishonesty.”

“Well,” the querent says. “I’m not terribly devious. But the rest is true. I’m angling for a promotion soon, and I did just finish a pretty large project.”

Ahh, 7–Snake is the Queen of Clubs, and thus can represent a person. “Do you work closely with a somewhat sly older woman?”

“Oh, yes, now that’s true! We work together on several projects.”

Now it might be a good time to look at some of the other possible people cards, such as 4–House, which can also be the King of Hearts: “There’s also a man here, stable and solid.”

“My boss, I suspect.”

“Could be. Judging from his closeness to 28–Gentleman, one of your signifiers, he likes you. There’s also an older man.”

“Yes, but he’s retiring soon.”

Aha. “Is he in a position of authority over you?”

“Not specifically, but he is well-regarded by most of my coworkers.”

“Coffin + Bear + Lily could indeed indicate his retirement, opening up a place (house) for you.”

The querent looks thoughtful. “So can this card, the Queen of Diamonds, 22–Crossroad also mean a person?”

“Possibly, but not necessarily. She’d also probably be a bit older than you, since she touches 30–Lily.”

“Everyone is older than me.”

“And she opens up (33–Key) opportunities and choices (22–Crossroad) for you.”

“I’m not sure who that is.”

“Keep an eye out, then.”

The querent later reported that he did in fact get the promotion, as predicted, and that the reading fit quite well. He still hadn’t identified the older woman, however, which might mean that it did not represent a woman after all.

Readings tend to go better when the reader can talk directly to the querent. When the two are separated, even by telephone, it’s sometimes hard to get the necessary context, as in the first Book of Life example above. However, even there, if I had read the cards more carefully the first time I would have seen what I had missed. The one bit of context I was missing was the querent’s sexual orientation, but really the dynamics of the situation remain the same even without taking into account that element. And the character sketch I drew of the querent’s partner (or ex-partner) was considered accurate, apart from sex.

I included both of these readings to illustrate that a true reader of the cards makes mistakes, needs feedback from the querent, and works with the querent to create meaning rather than impose it on a querent. Reading the cards—or any oracle—is a collaborative effort with the querent.