DIY

Every culture has its own means of divination, all of them different. And even different practitioners may regard symbols differently. For example, there’s a long tradition of reading regular playing cards—not the tarot and not the Lenormand—and applying meanings to suits, numbers, or combinations thereof. This reading of playing cards is probably what Mlle. Lenormand herself did. Among those who read playing cards, it’s not uncommon to find diverse meanings for particular cards. In the system I learned and employ, the Seven of Hearts means “emotional difficulty.” Just glancing around the web at other meanings, I see that for some it means broken promises, for others platonic love, for others yet a female friend. Surely, then, the skeptic might scoff, there can be nothing to reading the cards, or everyone would agree on the meaning of individual cards.

The fallacious nature of this skeptical argument becomes clear when applied to other means of communication. For example, it’s important if you’re going to study Spanish to realize that embarazada does not mean “embarrassed.” It may look similar, but assuming that a word means the same thing in Spanish as it does in English is likely to leave you embarrassed indeed (although probably not embarazada). From this difference in meaning, we cannot conclude that no language really communicates. They all communicate, about equally well, because the meanings are arbitrarily applied to words, not by any conscious effort, but by unconscious agreement among speakers. And this agreement may change over time. The Spanish word carpeta means “folder,” but in the southern parts of the United States, I understand that it has begun meaning “carpet” because of the similarity of those two words and a sort of unspoken and unconscious agreement to modify the word and its meaning.

Every system of divination is, at its root, DIY or “do it yourself.” Every diviner creates new meanings for the symbols of his or her system. At the same time, however, there must be some agreement with the Anima Mundi or those symbols will remain dead and useless. Just as each speaker of English develops his or her own personal way of speaking the language—what linguists call an idiolect—but cannot simply create new words or grammar without being badly misunderstood, each diviner creates his or her own variations of meaning but cannot simply decide what a symbol means without understanding it in relation to all other symbols in that system. We can consult the Anima Mundi’s opinion on what symbols mean by appealing to tradition, not blindly but with an intuitive openness and willingness to listen.

Try an experiment. Take ten slips of paper, and write a number on each, from one to nine, and then zero. Mix them up in a hat or upside down on the table, and then try to get into a divinatory state and ask for your phone number. Pull out the numbers one at a time. Did you end up with your phone number? I suspect not. Why not? Because for any symbol system to be an effective system of divination, it needs to follow some basic principles.

The first principle of all divination systems, which I’ve come back to repeatedly in this book, is that it serves as a method for listening to the Anima Mundi. In our example above, we listened—so listening is clearly not enough. The problem with the divination system of numbers written on slips of paper rests in the second principle of divination systems.

All good divination systems consist of a network of associated symbols. In the earlier discussion of the tarot, for example, I illustrated how cards in combination take on more meanings than merely adding the cards together. The Prince of Cups is a dreamy, thoughtful, poetic and emotional young person with a tendency to become distracted and start but not finish many projects. The Three of Swords is sorrow. Put them together and you don’t simply have a young, poetic man. who is sad—you have a commentary on the cause of the sorrow. Perhaps the sadness evolves from this tendency to dream bigger than one’s power to achieve. And if you add a third card to the mix, say the Nine of Cups, suddenly the entire meaning of the whole changes. Now, we see this sorrow is temporary because of unexpected good fortune fulfilling the wish of the young man represented. Now think of your phone number divination deck: the nature of the three in a phone number does not change when followed by the two. The symbols of the ten digits are part of a system, but not an associational system. The only association between the symbols of the digits and their places is whether they’re to be multiplied by ten, a hundred, or a thousand, and so on—and even this is missing in a phone number.

So therefore, the second principle is that a divination system consists of a network of associated symbols. By “associated” I mean that the symbols signify their meaning in association with each other. They are not isolated but form a community of symbolic meaning. In this community, symbols (for example, words) are not defined in isolation as in a dictionary, but defined in their relationships to each other. These networks can become extremely complex, and to have “knowledge” of a topic is to understand, intuitively or otherwise, the network of meanings that defines the relationships between its parts. A divination system, to be effective, apparently must have a certain level of associational complexity. In our deck, the network of meaning is not complex: each node (card) is simply one of a set of arbitrarily defined numbers.

The third principle of a good divination system arises out of the second. A good divination system does not reveal facts but meanings. A fact in isolation is not meaningful because it does not have a relationship with other vertices in a semantic network. Your phone number is a fact. The Anima Mundi, however, is a consciousness dwelling completely in meaning; for her, your phone number is nearly invisible. Just as we are unconscious of the individual muscle fibers moving in our legs as we walk, so she is unconscious of the facts that, together, make up meaning. If we wish to divine a phone number, we need to imbue it with meaning. How we might do this is beyond my imagination, but other such facts—the locations of missing objects, for example—becomes easy to divine when the diviner focuses on the meaning of the object, rather than seeing it as a lifeless material object. The more sensory and emotional connection we can have with a thing, the more it means.

Our number deck fails as a divination system again, because we have no sensory experience of numbers themselves. We have experience with physical objects reflecting the properties of the numbers: we have experience of “two pens” and “two cupcakes” and “two books” but not of “two.” And you cannot substitute the sensory and emotional meaning of “two cupcakes” for that of “two pens.” But a phone number doesn’t even have the physicality of that association. The area code 630 does not represent six hundred thirty of anything: it’s just an arbitrary code.

Finally, our number deck fails because of the fourth principle of a good divination system: completeness. For a divination system to operate well, it must represent a microcosm of the Anima Mundi’s consciousness. It must serve as a psychological map of her awareness, which is the entire universe. This map can be large-grained, and such a map might be more useful than an exact one—after all, a full-sized map of a place can never exist, without destroying the place it maps. Lon Milo DuQuette calls this quality of a divination system “perfection,”29 which is an apt description. The word “perfect” actually comes from a Latin root meaning “complete.” A tarot deck is “perfect” in this sense, because it divides up and maps the entirety of experience in more-or-less accurate proportions.

Sometimes one comes across a divination system, usually sold in boxed sets, that is made up by an individual or channeled from some supposedly spiritual source. Some of these fortune-telling decks are excellent, but some of them are “imperfect.” They sometimes have, for example, no indication of anything negative that could ever happen to anyone. Such a deck might be pretty and comforting, but probably is not terribly accurate. If you don’t give the Anima Mundi a way to say “watch out!” how will she warn you about the sharks?

So is our number deck useless? Not entirely. If we can create significance for these numbers, we can begin to create our own divination deck. We might not be able to use it to divine phone numbers (after all, they are facts and not meaning, and therefore not really what divination is for, just as you can’t smelt iron in a microwave). But we can use it for other purposes. If you take your ten numbers and begin to imagine what they could mean, what events they might represent, you’ve taken a few steps toward creating a divination system.

In defining these symbolic meanings, keep in mind that you’re dividing up the entire universe into ten chunks, so you need to be large-grained in your approach. You want big trends, not details. Let’s imagine that you decide, reasonably enough, that one indicates beginnings, two indicates partnerships or exchanges, and three indicates blessings, and so on. You might decide differently: three might indicate growth because a mother and a father create new life, or it might represent danger because a three-sided figure cannot stand stably on its point. Whatever seems most reasonable to you will work if you’re consistent. Now you have a deck suitable for marking large-scale trends and relationships in your life.

But it’s not very precise. It is a map with too few details, like one that mentions the existence of London and New York but little else between. Handy if you’re trying to find London from New York, not so handy if you’re trying to find Alsip, IL, from Dubuque, IA. You draw, say “one” and ask, “Well, great, beginnings—but what’s beginning?” What we have here is a list of symbolic relationships between ideas, but not the ideas themselves. Yet we cannot create a divination system that includes every possible idea in the universe, or even in our experience of the universe. Such a system would rapidly become cumbersome indeed, like a map of California the size of the state itself.

But we can add some general domains of human experience to the deck, to define our terms a bit. We could, for example, decide that the main interactions that people undertake involve emotional situations, represented by hearts; work, represented by sticks or staves; conflict, represented by swords (after all, we want to include all experiences, not just the good ones); and material possessions, represented by a precious stone, like a diamond. Now we have a deck with ten pips and four suits. We have the pips of playing cards without the court cards.

We can take these cards and write a general meaning on each card, a short title that expresses the nature of each card. For example, the Ace of Spades is the beginning of strife. That makes sense. Maybe we’ve decided that fours are stability, so the Four of Diamonds is financial stability. If threes are growth then the Three of Clubs is increased work. What we have now is a traditional fortune-telling deck, built from the ground up rather than memorized out of a book. And we can see, therefore, why the meanings might differ from reader to reader—my Six of Clubs is probably not your Six of Clubs.

We’re not bound by these numbers, the key of ten and the key of four. Any of the keys can be used to create a system of more or less complexity. These numeric keys survive as well as they do inasmuch as they represent a map of human experience, so any of them may be used to create meaning. Relationships between them can be multiplicative, as we’ve done here with the deck of cards, or additive, as the twenty-two cards of the major arcana are added to the deck of the fifty-six minor arcana. We could, for example, create a system that involved the three aspects of cardinal, fixed, and mutable, and the seven planets. If we multiply them, we’d end up with twenty-one tokens, a manageable number. Then we figure out how the combinations ring changes upon the symbols: fixed Venus is emotional stability; cardinal Venus may be the beginning of a relationship. Or we could ring the changes of each planet through the four elements: fire of Venus may be passion; water of Mars may be anger.

Or we could add the keys instead of multiplying them: we could take the twelve archetypes of the signs and create cards for each, then add to that cards for each of the elements. We could also combine methods, as the tarot does, and create one set of cards with multiplicative relationships and add to it another set of symbols: the planets through the elements, for example, and then the twelve signs on top of that to create a deck of seven times four plus twelve. And the possibilities for permutation are nearly endless. For example, geomancy and I Ching both permute in binary, zero, or one. In geomancy, there are four binary digits, represented by one dot or two in each of four lines to create sixteen figures. In I Ching, there are six lines, called a “hexagram,” each with a broken or whole line, to create sixty-four figures. In both cases, we get the same sort of multiplicative process described earlier.

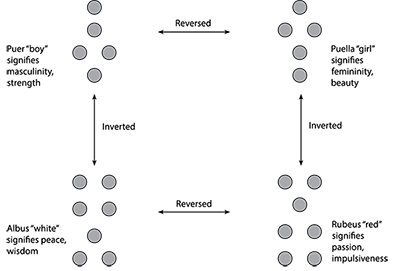

So many different divination systems make use of this multiplicative approach because it serves two purposes: first, it creates a complete system by covering all possible permutations of two different symbol systems or keys. Second, it assures relationships between symbols in at least two directions: it acts as a center for the arising of a web of meaning. In geomancy, for example, certain characters are opposites of other characters, and others are reversals of those characters, so each symbol has a relationship with, often, two other characters. And anyone who has worked with the I Ching more than simply looking up the commentary on each hexagram realizes that each hexagram is composed of two trigrams, one on top of the other, and two inner trigrams, interlocked in the middle of the figure, which themselves create a hexagram.

Some divination systems, however, simply include a list of archetypes and trusts in the tradition to assure both completion and relationships between them. I’ve used cards marked for each of the twelve Olympian gods, for example, to some good effect, because each card invokes a series of stories. For example, if I lay out Aphrodite next to Ares, I can tell the story of their relationship, and if Hephaestos comes up, then I can tell the story of how he caught them in a net for the gods to jeer at—a clear divinatory message of “whatever is being kept hidden will be uncovered by cleverness.” The completion or perfection of this system relies on the reader’s power of association and memory. The runes are one such system, in which each of the runes acts as a hyperlink to various stories, legends, and practices of the Norse people.

Often these latter systems, in which a series of notions or archetypes create the divinatory system, may be codified into a text-based divination system. In this case, the relationships between symbols exists in the stories themselves, and the symbols alone mean relatively little unless one knows the texts. In the I Ching, the hexagrams relate to each other through their component trigrams, but they also point to various texts with consistent characters, like “The Superior Man” and consistent symbolism, such as “crossing a great water.” The Yoruba divination system, Ifa, uses symbols very similar to the geomantic symbols to point to a set of oral verses. The diviner and querent work together to apply the oral verses indicated by the fall of the shells to the querent’s situation.

All truly useful divination systems will eventually situate their symbols into a narrative framework. If the symbols have no “story-meaning,” then they’re impossible to apply to life. For example, one can say that the rune Tiwaz means courage and success, but it’s more useful to tell stories of Tyr and watch the querent’s reaction. Similarly, the Fool in the tarot means beginnings, setting out, and so on—but you’re better off recognizing that he is a character in a story. He’s not simply the idea of setting out: he’s a person setting out, with a bag on his shoulder (what’s in the bag?) and a dog at his heels (is the dog helpful or harmful?) and a cliff before him (is he aware of it? Will he fall?). Each of these questions is a story hook that you can use to connect the reading to the querent’s life situation.

In creating your own divination system, it helps to begin by recognizing the kind of stories you wish the system to tell. If you want a divination system to tell you specifically about one area of life, you can leave out some symbols, as long as you’re complete in that domain. Similarly, if you want a divination system that can be used universally, like the tarot, you need to include every possible life event, to some degree, so that you can tell any story that arises.

Moreover, you need to recognize that stories are not single entities, but symbols strung together into meaningful patterns. A story is not mechanical. I remember when I was learning the tarot I picked up a fairly well-intentioned book with lots of good advice, but one of the things it suggested was that in a drawing for a yes/no question, an upright card was always yes and a reversed card was always no. Always in search of mechanical simplicity, I tested this technique and found it right—about 50 percent of the time. What I found more often was that the meaning of the card itself told the story that answered the question, and not always simply—because, in reality, there are no simple yes/no questions. There are stories that we tell ourselves about our lives.

In order to take advantage of the organic nature of these stories, it helps to have symbols that work together in combination. A. O. Spare, in a famous essay on cartomancy, suggests creating your own deck, assigning unambiguous but fairly broad meaning to each of the cards. The complexity comes from creating a story of the cards as they fall:

It is the combination of certain cards that indicates the meanings of the more important events and episodes of life. For example: a combination of Spades - ‘Nine,’ ‘Ten,’ and ‘Ace’ - when so closely juxtaposed would mean death very soon and, in combination with cards meaning ‘accident,’ ‘sickness,’ ‘hate,’ would mean death by accident, sickness, murder or suicide, and so on covering every possible event.30

If we can gloss over his characteristic grimness, we see that he goes on to suggest that the more cards necessary to create a meaningful combination, the more unlikely the event. Marriage might be indicated with two or three cards; marriage to—oh, say—the duke of Ostfriesland, however, might require more cards.

One advantage of sticking with the keys of four and ten mentioned earlier is that we already have pre-made cards with those numbers associated. We can use playing cards as a divination system right out of the box.

Methods of reading regular playing cards vary in terms of how much the suits and numbers mean. One way of creating a divination system is simply to apply an arbitrary meaning to every card. This seems to be what Spare is suggesting. The memory load of such a practice is high. But the advantages are that you can get every symbol you want, somewhere. He suggests writing them on the cards to aid memory.

We can also use our keys, as previously discussed, to create meanings. For example, we can decide that each of the digits from ace to ten represents part of a story. The ace is the beginning, the twos are the ally who aids us. Three is the desire that drives the plot. Four is the setting. Five is the obstacle that must be overcome. Six is the way through. Seven is the weapon we use. Eight is the plan. Nine is success. Ten is completion. Now, we can decide that each of the suits represents a domain of experience: hearts are emotion; spades are the mind; clubs are activity and work; diamonds are money. Now the Five of Clubs is an obstacle at work. The Two of Hearts is an ally in love: a friend. The Three of Diamonds is the desire for money. The Seven of Clubs is the tools of our trade. The Seven of Spades is our wits. The Nine of Hearts is success in love.

Another system, the Hedgewytch system, described on an unfortunately now defunct website, gave each digit a meaning based partially upon the appearance and arrangement of the pips. Ones are beginnings. Twos are partnerships and exchanges. Three is growth. Four is stability. Five is the body and its accoutrements. Six is the path. Seven is an obstacle. Eight is the mind. Nine is success. Ten is completion. Then the suits are divided by color: red is the pleasant domains of love (hearts) and money (diamonds). Black is the less pleasant domains of work (clubs) and trouble (spades). Now we can see that Three of Spades is an increase in worry; Two of Diamonds is a monetary partnership.

The court cards, in most systems of cartomancy, often represent people, with jacks being juveniles, queens being women, and kings being men. So the King of Spades might be a man who uses his wits: a lawyer or judge. A Jack of Diamonds might be a young man who has just begin to gather “goods”—a student, perhaps. Traditionally the court cards are also given domains of their own: jacks are often, across systems, associated with messages. So the Jack of Hearts is a message about love. The Hedgewytch system associates queens with “truth” and kings with “power,” so the Queen of Spades is an unpleasant truth; the King of Diamonds, the power of wealth.

The Hedgewytch system in full is complex; it is a pity that the site that described it has disappeared. Hopefully, the author of the system will publish it elsewhere.

But we can create our own, just as easily. The benefit of using playing cards is that they are, unlike the tarot and unlike the Petit Lenormand, nearly blank. We can project whatever symbolism, whatever image, we have on them. That’s also the source of their intimidation. They require us to map out a universe before we shuffle. Some readers of the tarot prefer unillustrated pip cards—minor arcana without images—for just this reason: they can project an interpretive framework on them themselves rather than having it imposed by the artist.

Even if we don’t create our own divination systems, we all do create the stories that the cards or runes or I Ching tell us. We create the combinations and links between symbols that create meaning from the system, and my combinations differ from yours, because the stories I habitually tell and experience also differ from yours. Some books misunderstand this process of story-telling, and list long lists of combinations that one is, presumably, to memorize. However, they’re best used as examples for the basic idea, and not as mechanical meanings imposed upon the story. The story imposes meaning on the cards; the cards do not impose meaning on the story.

Any “perfect” or complete system will lend itself to story-telling, and story-telling lends itself to divination because stories are predictable. Once you understand their structure, it’s difficult to be surprised. One of the jokes among those who study literature is that movies are ruined for them forever: there are only a few limited plots, recycled again and again, and once you learn them, movies become predictable. Of course, we still watch movies, because although we know how the movie will end, we don’t know for sure how the movie will get there. Divining the future lets us see how the plot we’ve chosen to live out is likely to end, but that doesn’t rob us of the interest of living it. And unlike characters in a movie, we can choose our plots, change our future, and divination can help us do that. Do-it-yourself divination isn’t just creating a new system of cards or runes, or constructing and learning new ways to combine the symbols of your favorite system: it’s also learning how to write the story you live yourself. Divination is a language that works in both directions.