A Brief Description

of the Major Arcana

Since one of the purposes of this book is to explore the relationship between the tarot and the Petit Lenormand, it’s necessary to establish what I mean by “tarot.” Most readers—probably most people in general—have some notion what the tarot is, even if they’re not sure how to pronounce it. But there are some misconceptions (some that I have even helped spread, unintentionally) so I’m going to quickly cover its history and then explain meanings of the twenty-two major arcana cards, at least as I see them. I imagine most of my readers will have their own meanings, and that’s fine, but it’s worth establishing a baseline.

The tarot is a fifteenth-century invention, so it pre-dates the Lenormand by centuries. However, we don’t have much evidence of divination with the tarot until the eighteenth century. Therefore, the tarot and the Lenormand are closer siblings than might be supposed. Still, the images of the tarot are older: the tarot borrows from a medieval world long since passed by the time they were used for divination.

Prior to its use in divination, the tarot was used to play card games. These games, similar to Bridge, involve the taking of tricks, and as far as we can tell there was no esoteric meaning behind the games themselves. Moreover, there wasn’t much standardization between decks. Early decks vary in the number of cards, especially in what we now call the major arcana and what were then called the trumps. The fixed order and images of the trumps are relatively late. And the purpose of the trumps, at least as far as early tarot goes, was to take tricks and thus score points.

We do have some religious proclamations against the tarot, not for any perceived magical characteristics of the decks, but because they were used in gambling. Sometimes, condemnations—usually in the form of outdoor sermons, such as those by San Bernardino di Siena, a fifteenth-century Franciscan—were followed by a “bonfire of the vanities,” what we now refer to as a book-burning. The items burned along with tarot and playing cards often included other games, such as backgammon sets and similar items, as well as “temptations” such as make-up and books of poetry.

Like many others, I used to think that playing cards derived from the tarot. It’s a reasonable assumption. Unfortunately, it’s wrong. We now know that playing cards probably pre-date the tarot. The earliest four-suit, fifty-two-card decks we have date from the late fourteenth century. Our earliest tarot decks, however, date from the early fifteenth century. It’s now generally thought that the tarot resulted from the adding of the trumps to a variant deck of playing cards.

At this time (the early fifteenth century) we have a situation where multiple card games have their own decks, and the purpose of those decks is gaming. Symbols of some important ideas appear in the trumps: virtues, vices, figures from mythology. But these began as decorations: the cards represent nothing, ultimately, but numbers to be used to determine the rank of trumps.

It’s also common to hear that the Fool, the unnumbered trump in the early tarot decks, became the joker in modern playing decks; however, there’s overwhelming evidence that the joker was introduced in America in the nineteenth century. A good story falls apart.

Over time, esoteric images began to appear on the cards. And that’s really no mystery: when the tarot and playing cards both began to be used for divination, esoteric images were added to the more pictorial of the two. And in the early twentieth century, when A. E. Waite designed his tarot deck with the help of the artist Pamela Colman Smith, he (or, more likely, she) added pictorial elements to the minor arcana, or pip cards.

For our purposes, I want to focus mostly on the major arcana. The relationship between the images of the major arcana and those of the Lenormand is fruitful. I also wish to focus on the esoteric or inner meaning of these symbols; obviously the tarot was used to play games at one time (and, in Europe, still is). But both the tarot and the Lenormand have an almost equally long tradition of divination.

The major arcana of the tarot has twenty-two cards. I will discuss the images on the Rider-Waite-inspired Universal Tarot cards that follow, which will probably match most decks you select. However, an older deck has some popularity among tarot diviners: the Tarot de Marseilles, which differs in some regards from the Rider-Waite. I’ll point out interesting variants as they occur, as well as some keywords for meaning. My descriptions are cursory; you’ll find fuller descriptions and meditations on the tarot in Rachel Pollack’s Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom, a classic on the tarot.10

The Tarot Trumps

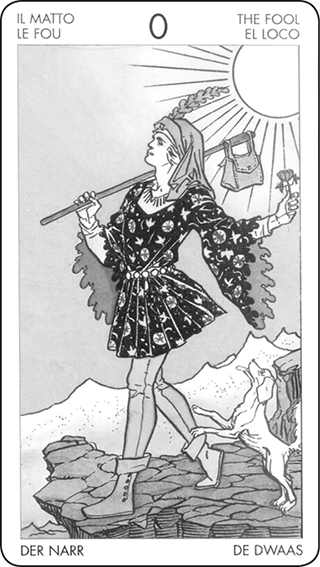

0–The Fool

A young man chased by

(or accompanied by)

a dog is about to step off a cliff.

He’s holding a bundle.

Keywords: Beginning. Folly. Innocence.

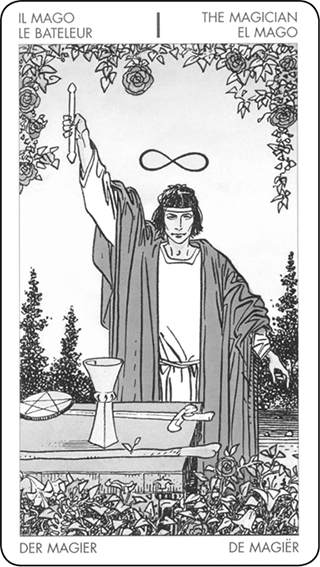

I–The Magician

A magician dressed in ceremonial robes

stands before a table set with his elemental tools.

He holds his arms in a posture indicating

the union between above and below,

an important occult maxim.

Keywords: Skill. Praxis.

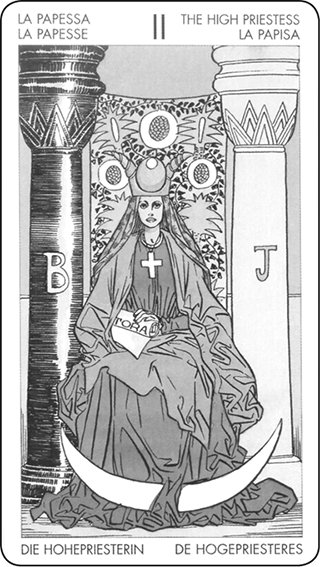

II–The High Priestess

A woman sits on a chair, a scroll in her hand.

Behind her is the veiled entrance to

the sanctum. In the Marseilles decks,

she is the Papesse, a female pope.

Keywords: Wisdom. Theory. Secrets.

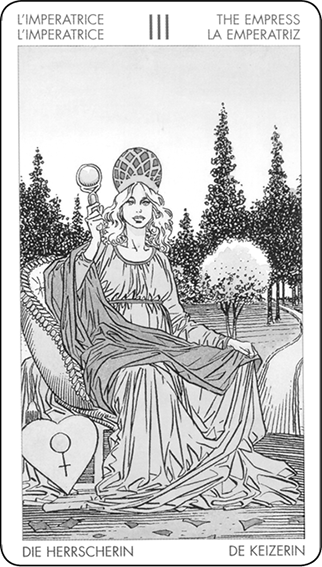

III–The Empress

A woman sits on her throne in a natural setting,

a heart-shaped shield emblazoned with the

sign of Venus at her feet.

Keywords: Love. Nature.

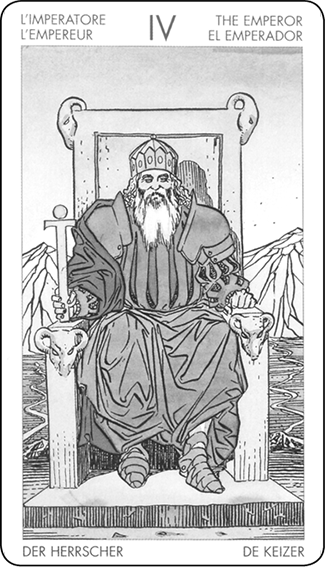

IV–The Emperor

A man sits on his throne,

a mountain behind him.

He holds the tools of power.

Keywords: Authority. Civilization.

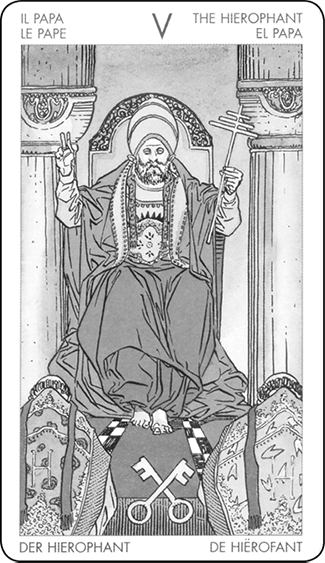

V–The Hierophant

A man sits on a throne,

two acolytes kneeling before him.

He holds his hands in a blessing gesture.

In the Marseilles, this is the Pope.

Keywords: Education. Dogma.

Convention.

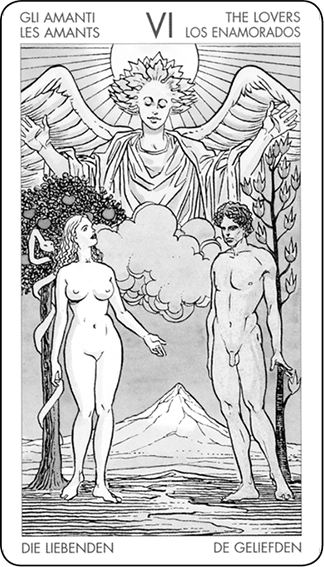

VI–The Lovers

Two people stand with an angel

blessing their union.

A tree in the background hints

that this is Eden.

In the Marseilles, a man stands

between two women and Cupid

hovers above him.

Keywords: Choice. Union.

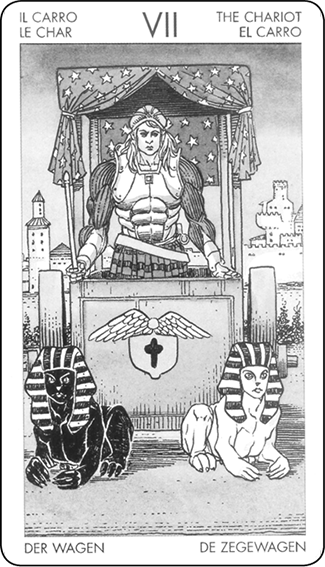

VII–The Chariot

A man drives a chariot

pulled by two sphinxes

of different colors. In the

Marseilles, these are horses.

Keywords: Progress. Will.

VIII–Strength

A woman wrestles a lion. In the

Marseilles, this is card XI.

Keywords: Strength. Power. Life.

IX–The Hermit

A lone man on a mountain

shines a light in the darkness.

Keywords: Seeking. Teaching.

X–The Wheel of Fortune

A wheel inscribed with mystic signs

spins, while four mystical creatures

watch from the corners.

Keywords: Reversal of fortune.

Luck. Improvement.

XI–Justice

A woman, blindfolded, holds aloft a

sword and scales. In the Marseilles,

this is card VIII.

Keywords: Balance. Redress.

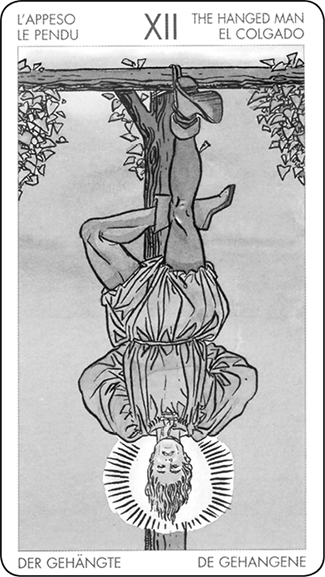

XII–The Hanged Man

A man hangs upside down,

his arms and legs folded into

a mystical symbol.

Keywords: Sacrifice. Stasis.

Initiation.

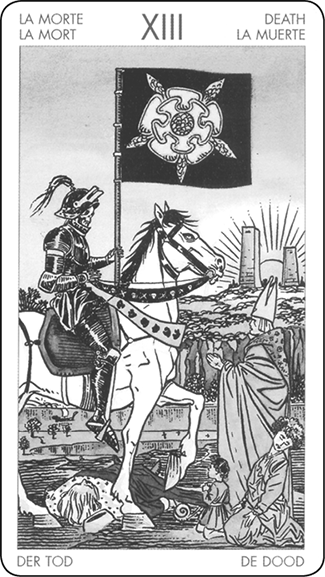

XIII–Death

A skeletal figure on a horse receives

tribute from a bishop on a field

filled with death.

A child plays below. In the Marseilles,

Death reaps the dead with a scythe.

Often, in the Marseilles,

this card is unnamed.

Keywords: Transformation. Endings.

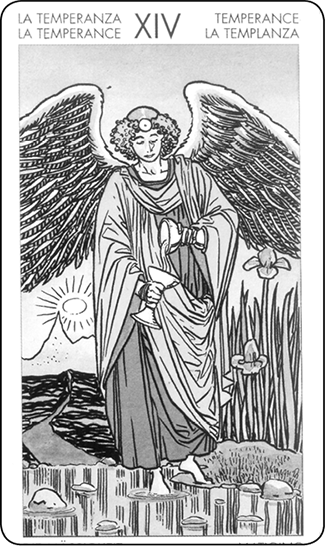

XIV–Temperance

An angel, one foot on land and

one in water, mixes water from one

cup to another.

Keywords: Art. Care.

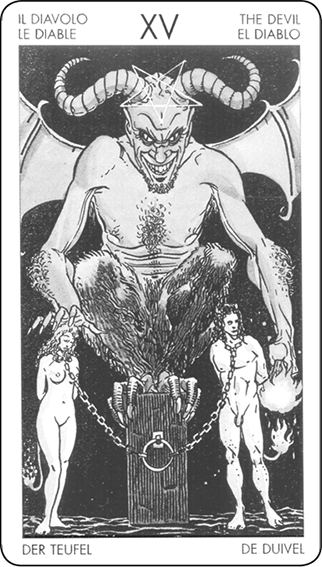

XV–The Devil

The devil sits above two chained figures,

offering them a sign of ironic blessing.

Keywords: Bondage. Matter.

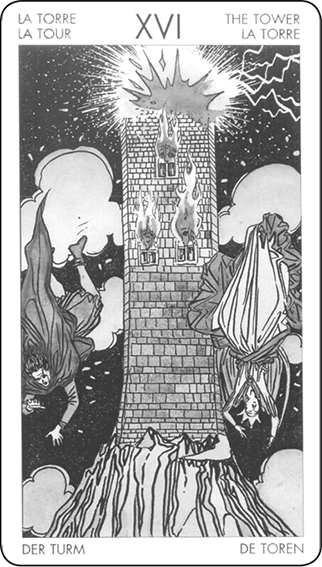

XVI–The Tower

Two figures fall from a tower

blasted by heaven.

In the Marseilles, this card is called

the House of God.

Keywords: Destruction. Violent

transformation.

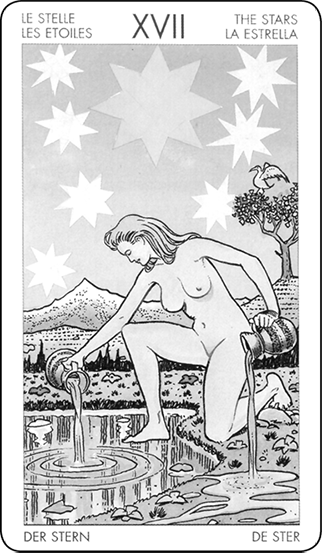

XVII–The Star

A woman, nude, pours water

into a pond

and onto the ground.

A large star shines above

her in a starry sky.

Keywords: Hope. Spiritual love.

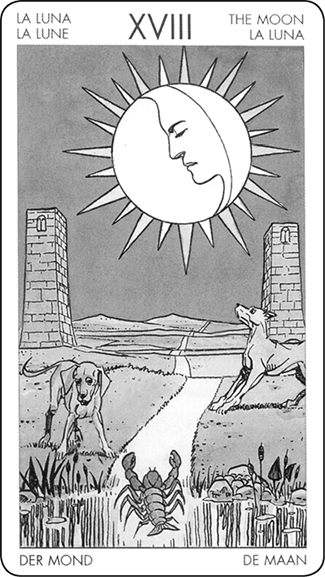

XVIII–The Moon

Two canines howl at a moon rising

between two towers.

A road weaves between the towers.

Keywords: Deception. Intuition.

Mystery.

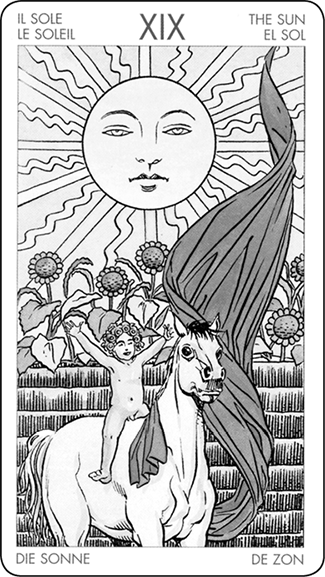

XIX–The Sun

A child plays on a horse below

a shining sun.

In the Marseilles,

two children play, with no horse.

Keywords: Joy. Success. Blessing.

XX–Judgement

The dead rise from coffins at the

blast of an angel’s trumpet.

Keywords: Advancement.

New phase of life.

XXI–The World

A hermaphrodite dances in a wreath while

the four mystical animals look on.

Keywords: Completion. Perfection.

These thumbnail sketches illustrate the domain of the major arcana. These are major concerns, almost philosophical in nature. When compared to the Lenormand, the Lenormand seems almost trivial. But is it? When we compare these symbols, we’ll discover an interesting disjunction between fortune-telling and divination, and as we’ll see, the roots of that disjunction not in esoteric purity but in social class.

10. Rachel Pollack, Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot (San Francisco: Weiser, 1997).