Occult Symbolism

and the Anima Mundi

Here I am driving in the western suburbs of Chicago. I’m singing along to The Killers on the radio and trying not to think about the fact that I just absentmindedly took a swig from the three-day-old cup of coffee in my cup holder. My mind is, to say the least, occupied, but I nevertheless press on the brake pedal when I see the octagonal sign ordering me to STOP. It doesn’t matter whether or not the words are there; I don’t read the sign as a word. I read it as a symbol that leads to a physical reaction before it ever meets my conscious mind.

I do more than stop, though. Because of that sign, I know that I have to analyze the situation in certain ways. First, I have to realize how many signs there are. If there are only two, then I have to show some care to cross-traffic. But no, there are four. So I have to recognize which cars have right of way. I time which of us gets to the sign first, but two of us come to the sign at the same moment. The white Ford to my right and I have a photo-finish race to the sign, so I glance at the driver and nod, and he pulls forward cautiously. As soon as he’s through the intersection, I start rolling cautiously, making eye-contact with the other drivers.

I do all this during about three bars of the chorus of “Human.” Now, I’m a clever guy, but the guy in the Ford kind of looked like he would have a hard time tying his shoes without a diagram, and I know for a fact that some of the people on the streets can’t do simple math in their head or read without moving their lips. Plus, I’m such a genius that I forgot to throw out the old unfinished coffee in my cup holder—and worse, I drink it without thinking days later. How is it possible that nearly all of them—and me, on a very bad day—can interpret such a complex symbolic system so easily?

All humans are geniuses at one thing: interpreting symbols. No matter their level of intelligence, they’re capable of using language unless they’re suffering a specific form of brain damage. One may not know as many words as another, just as some may not know Hungarian, but they can express any thought they have and understand any idea couched in words they know. Language is nothing less than a complicated symbol system, much more complicated than mere traffic signs.

The old definition of symbol is “anything that stands in place of something else.” A stop sign stands in place of the act of the stopping. The word “orchid” stands in place of the green thing not getting enough sunlight in my living room. This definition is fine as far as it goes, but it doesn’t take into account that symbols don’t actually exist in isolation. A stop sign means very little hanging on a dormitory wall. It has to exist in the system of other traffic signs. If I hung up a piece of paper with the word “stop” typed on it, it would have no effect whatsoever other than to confuse people. It’s still a symbol standing in place of the act of stopping, but it doesn’t work because it’s not part of the system.

That system exists only in the minds of the people who use it. A symbol has no independent existence outside of the mind. Note, however, that “people” is plural. If I walk around speaking a made-up language, I cannot be said to be communicating unless someone else learns it. It’s not that the language is made-up that makes it unreal—after all, I can speak to someone in Esperanto or, if I take the time to learn it, Klingon, and be understood—but that it is not part of a shared system.

This shared system does not exist only in human minds, however. Or at least, so I would contend as a panpsychist. A panpsychist believes there is a mind underlying all of reality. I could call it “God” perhaps, but it’s not much like the traditional God of Islam or Judeo-Christianity. Instead, I’ll call it by the name the ancients gave it: the Anima Mundi, or “soul of the universe.” The Anima Mundi is a mind as well, and it shares some symbols with us. It probably doesn’t pay much attention to traffic signs, but like all of us, it’s interested in the symbols that refer to parts of itself. If we want to get someone’s attention at a party, we start talking about their lives. Similarly, if we want to get the attention of the Anima Mundi, we start using the symbols that refer to parts of it.

Those symbols themselves have a grammar, just as words in a language do or traffic signs do. The ancients, being clever little buggers, organized these symbols according to a general scheme of reality. This scheme, to the literal-minded, seems to suggest that the Earth is the center of the universe. In reality, however, the ancients recognized that, in the infinite, any perspective is the center. Therefore, just as maps made in America tend to put North America at the center of the world, they recognized that putting the Earth at the center made sense, since we happen to live there.

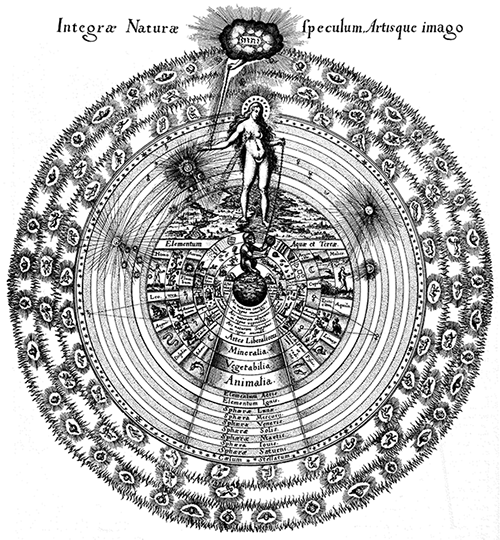

The image following, the Mirror of Nature, is a famous picture of the Anima Mundi made by Robert Fludd, and it served a specific purpose. Namely, it provided a thumbnail outline of the grammar of the symbols the Anima Mundi seemed to speak in, in a handy cheat-sheet like those laminated summaries of topics you can get at bookstores. It was a study and memory aid. Unfortunately, we’ve lost the art of organizing information in graphical form.

It is tempting to go into the meaning of every squiggle and symbol on this chart, but I heroically refrain, and instead will point out only two things. First, notice that the artistic style of this engraving shares some similarity with the art of the tarot, especially as it evolved into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is clear that Waite and Smith were influenced by the symbolic grammar of this kind of diagram. Second, the woman at the top with the celestial pasties is the Anima Mundi, the soul of the world. To the Renaissance magician, she is the explanation for why divination works.

In the Neoplatonic worldview of the Renaissance magician, reality as we perceive it is a shadow of a living mind, the cosmic nous or consciousness. Everything that exists is a reflection of an idea or form in that Nous. The thing that governs the way those ideas work out in time and space is the psyche, or in Latin, the anima, usually translated “soul.” The anima governs the processes of things. If the form is like a recipe for cookies, the anima is the process of gathering together all the ingredients and following that recipe to create material cookies. Our own soul is what governs the process of being a person, of being alive. The mundus, which means both “world” and “universe” in Latin, also has an anima or soul. It is the anima that gives a thing the power to act. The universe is alive, and it is conscious, and through divination we speak to it by giving it a place where it can act. This old philosophy is the root of a contemporary philosophy, panpsychism, which argues that all of reality is consciousness—not a mind in anyone’s particular head, but Mind in general.

The materialist perspective is that the mind just grows out of matter: it arises as a side-effect of a particular chance arrangement of molecules, and any sense of self or feeling of free will is an illusion. Some studies have shown that, for example, the neurons in our brain begin the process of carrying out a choice before we are conscious of making the choice. If you decide to move your arm above your head, your brain begins the process of starting the movement well before you decide that you desire to move your arm. One interpretation of this data is that our choices are illusory; another interpretation is that our choices are not illusions, but we are not always self-aware of every bit of our consciousness. If consciousness resides, even in some rudimentary form, in the cells of our brain—or, for that matter, the very molecules of our flesh—then it might stand to reason that such a consciousness could affect the body itself without our self-awareness figuring into it.

One panpsychist perspective is that matter instead grows out of mind. Consciousness, then, comes first, and matter is merely the grossest form of that consciousness, information given solidity and structure. DNA does not encode genetic information: DNA is genetic information made solid. When a piece of DNA unzips in order to replicate, that information isn’t gone—it’s still present, even if the DNA itself has changed form temporarily.

All this philosophy boils down to one point: if the universe is conscious, we can communicate with it. It is not, however, conscious the way you and I are conscious. It doesn’t worry about its property taxes, make an appointment to have its piano tuned, or wonder if it should make another pot of coffee to get through the day’s quota of writing. It does other stuff that we don’t much worry about: calculating, over and over, various universal constants; giving rise to the structure of space and the directional arrow of time; ensuring and sustaining physical laws that allow matter to exist. So if I want to know which of the three piano tuners I’m considering to call, how could I get that information from the Anima Mundi?

First, we can’t assume that English (or Polish or Russian or Spanish) is the language the Anima Mundi will speak. Clearly it’s Latin, according to Fludd—and Latin written in a hinky handwriting … wait. No, actually, Fludd does give us the language the Anima Mundi speaks, very clearly in this diagram. The Anima Mundi speaks in symbols.

Now, how can we expect the Anima Mundi is capable of suggesting a piano technician? We can’t specifically, but we do know that piano technicians are part of this universe, and share in the thoughts of the Anima Mundi. It’s not as if the Anima Mundi thinks, “I’ve got to make sure that the strong nuclear force adheres these atoms together in these planets, but those piano tuners can take care of themselves—if they explode into a fine red mist, I don’t care. I’ve got bigger stuff to worry about.” It fortunately doesn’t work that way (and good thing, too—my piano sits on a very nice rug).

So, how do we ask the Anima Mundi to recommend a piano technician? We home in on the issue—called the quesited in traditional astrology and geomancy—and we seek a pattern of symbols around it. We can do this by looking for omens—the flights of birds, the movement of clouds or lightning, whether or not various coincidences happen—but this method requires a level of intuition and self-honesty that isn’t always easy to come by. Instead, we can address a particular pattern of symbols created through observation of the world, either in preexisting patterns (such as astrology) or in “randomly” created patterns (such as cartomancy).

Every culture has its own set of symbols just as every culture has its own languages. In many ways, the system of symbols used by a culture are a language, but one that’s used specifically to talk to the Anima Mundi and understand her responses back. In the Western occult tradition, most systems of divination can be broken down into symbols in sets of two, three, four, seven, and twelve. Fludd’s diagram gives us the symbols in sets of two, three, four, and seven, and also shows how they interact with matter.

Symbolic elements arranged in pairs naturally fall into the particular relationship of opposition. Similarly, symbols arranged in threes, fours, or sevens have a tendency to fall into similar patterns. Therefore, I refer to symbol systems by the number of items in them, which I will call their “key,” as in a piece of music. Just as the key of music determines what relationships the notes will have with each other, the key of a symbol system determines the kinds of relationships the symbols will have. In the key of two, for example, we can have items that are opposites (like on and off, good and evil) or complements (like right and left) or the poles of a scale (like hot and cold). Any set of symbols based on the key of two will be arranged in one or several of these relationships.

In the key of two, we have the alchemical arts of solve and coagula, or separation and combination. These are the no and yes of the Anima Mundi, and the simplest oracle is, perhaps, the coin. Even complex systems of divination, such as astrology, can be reduced to a “yes” or a “no” answer.

When applied to cartomancy, we can see how symbols in both the tarot and the Lenormand are sometimes arranged according to the key of two. For example, we have 28–Gentlemen and 29–Lady, which exist in binary pairs; we also have 31–Sun and 32–Moon. We can see that objects in the key of two often come in sequence in the Lenormand. In the tarot, we have similar pairs: I–The Magician and II–The High Priestess and III–The Empress and IV–The Emperor, among others. Again, we see these binary pairs often represented in sequential cards. In addition, there are some cards that contain the idea of twoness in themselves, such as VI–The Lovers in the tarot and 22–Crossroad or 12–Birds in the Lenormand. But you can only go so far with the key of two. Not every question can be reduced to a yes or a no, and playing Twenty Questions with the Anima Mundi isn’t efficient.

More complex scales of symbols are therefore necessary. Each of the more complex scales begins with the scale of two, however. Reality probably isn’t dualistic, but our minds are and we experience the world as if it is organized in pairs. Deconstructionist philosophers have shown that the duality we take for granted is arbitrary, and so is language. “Arbitrary” doesn’t mean “not useful” or even “unreal.” It merely means it has no necessary connection to reality. But since the nature of “reality” itself is a vexed question to the appropriately skeptical magician, there’s no real reason to expect our symbols systems to be identical to the territory they map.

If we add a middle element to the scale of two, we have the scale of three. In Fludd, this scale manifests as the three kingdoms of mineral, plant, and animal. In astrology, they appear as the three qualities of fixed, cardinal, and mutable. And in alchemy, they appear as salt, mercury, and sulfur. I’ll refer to them by their astrological names, only because it’ll become important when we get to the scale of twelve later. The fixed quality is the essence of stability and form. But nothing remains unchanging. The force that causes the change of form is the cardinal (from the Latin word for “hinge”) quality, represented in alchemy by mercury, which hovers between liquid and solid. The instability that results is the quality of mutable.

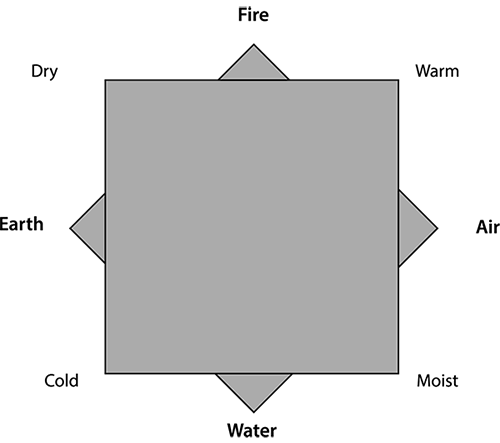

If you take two different forms of the key of two, and place them across each other as in the figure on the facing page, you’ll see they create a key of four. For the four elements, these two polar opposites are hot and cold; dry and moist. Air is hot and moist. Fire is hot and dry. Water is cold and moist. Earth is cold and dry. Of course, nothing is completely dry or completely hot, which means any given thing falls between these two things in relationship to other things on the scale. A towel might be dry or moist, but only in relationship to other items. If it is drier than your skin, it’ll feel dry. If it’s moister than your skin, it’ll feel moist. My coffee is warm, but only in relationship to ice-water, because it’s been sitting there for a couple hours. And when someone spits out cold coffee, it’s often the temperature that they’d spit out as “warm” in a soda. So a particular item isn’t “earth” or “air.” Instead, it’s on a scale between four poles. The elements aren’t four little boxes to put ideas in; they’re more like four compass points to help us orient an object.

A lot of magicians don’t know where this four-element system comes from, but the history is interesting and illuminating. Empedocles was a Sicilian philosopher born in about 490 BCE. As a Pre-Socratic, he was mostly concerned with questions of ontology or being. The main philosophical question of that time was about the basic stuff of reality. Different philosophers had different notions, but it was Empedocles who eventually came up with the notion that perhaps there were four different “roots” to reality, and that the complex relationships we observe are merely the interactions of these elements in combination.

It’s easy to laugh at this theory as naive, but doing so would be an arrogant dismissal of what was really a sophisticated idea. Empedocles wasn’t interested in figuring out atomic elements in the sense we use them now. He wanted to explain his observation of an ever-changing world, and in this he succeeded. He provided a heuristic that even those familiar with our more complex system of physical elements still adopt to explain phenomena.

Empedocles wanted to explain the physical universe, and in the action of matter he recognized two forces—love and strife—that contended against each other constantly, neither entirely winning and neither entirely devoid of the other. These forces were not just metaphoric: elements came together out of the same sort of love that humans felt for each other, and separated due to the same sort of strife. The elements were characters in a cosmic drama, or perhaps ideas arranged by successive acts of synthesis and analysis in the mind of the universe.

Many contemporary magicians use the elements as metaphors of emotional or mental states, and the understanding of Empedocles’s panpsychism opens the door to this understanding. Perhaps it’s not even metaphoric to say that a lake is calm—perhaps water and emotional states are linked underneath the surface of matter. Traditional and not-so-traditional correspondences abound. The advantage of making these correspondences is that it places our experiences into a framework. Just as the key of two offers a set number of relationships for the items placed in it, so the key of four creates a frame that describes relationships.

For example, fire and water are antithetical and cannot long endure each other. Similarly, we might say that the passions of lust and rage cannot long endure the emotional depth of water. That implies that these two elements are always in a condition of strife, which would lead to the entire universe arranging itself in a scale of two against water and fire. Since that has not happened, there must also be a way for love to bring the two together—and we can witness the judicious application of fire to water to create and transform and nourish: making soup, for example. And in human relationships, passion and strife do not lead to deep and meaningful relationships, while passion and love do.

The elements are not merely physical things, but exist in all worlds. Agrippa writes:

The elements therefore are to be found everywhere, and in all things after their manner, no man can deny. First in these inferior bodies feculent, and gross, and in celestials more pure, and clear; but in supercelestials living, and in all respects blessed. Elements therefore in the exemplary world are Ideas of things to be produced, in intelligences are distributed powers, in heavens are virtues, and in inferior bodies gross forms.11

Therefore, if we can observe the interaction of elements in one world, we can assume the same interaction holds for other worlds as well.

Each of the four elements is associated with ideas in the mind of the Anima Mundi by metaphor. The element of earth is the idea of all solid things, both literally and metaphorically. Stability and materiality are the characteristics of earth. Earth is cold and therefore passive. In the world of human events, earth represents physical economy and the body. The idea of water is also passive, but unlike earth, changes according to its environment. In the world of human events, water—because it so easily combines together—represents relationships and the emotions that arise from them, both good and bad. Air, on the other hand, is active and pervasive, and so among human concerns represents thoughts and communication. At the same time, we know that air can be a destructive force, just as the mind can be, and therefore it also can represent strife, particularly strife arising from thoughts. Fire, unlike water, does not change according to circumstances, but causes change. It is also active and can represent those emotions we imagine to be “hot,” as well as activity itself; therefore, it often symbolizes work and labor in human events.

The advantage of a symbol system like this is that it can reveal some relationships and exclude others. It organizes and categorizes thought, which allows communication. In other words, it provides a grammar of symbols we can use in divination to understand relationships between ideas we place within it. And we can classify certain cards in both decks by the element they seem to partake of (which may not be the element they are traditionally linked with in some systems). In the Lenormand, 21–Mountain is clearly earthy, while in the tarot, XI–Justice is very airy. And, of course, some cards again contain the whole key, such as XXI–The World in the tarot. Still, reducing everything to four categories may not be sufficient. And for Fludd and his contemporaries, the four elements were sublunary, meaning that they lay underneath the orbit of the moon. They were, therefore, best suited as symbolic placeholders for material, everyday things.

The key of seven, on the other hand, represented celestial ideas. In practice, plenty of emotional and intellectual ideas occur among the elements, and plenty of practical quotidian things occur in the symbol system of the seven planets. But in general, Renaissance and medieval magicians wanted to separate the functional world from the mental world. An easier way to conceive of the difference is in terms of change. The elements are in a constant change of flux, but the seven visible planets move slower and, with the exception of the moon and Mercury, represent ideas that work out longer in time and are more resistant to change.

The seven planets of antiquity, as well, influence both the physical world and the celestial world. It’s possible to file everything in the world under some combination of elements and planets. According to the doctrine of signatures, everything reveals its inner nature by its outward appearance. So if you pick up a rock and look at it with full attention, and are familiar with the correspondences of the planets and elements, you’ll soon see what pattern that rock holds in the mind of the Anima Mundi. Obviously, being a rock, it is of earth, but perhaps it is lighter than expected, which might indicate some air, and perhaps it is red, which might indicate fire and, in the planetary realm, Mars.

Just as the elements are not merely physical things, so the planets do not refer only to the celestial bodies. It would be safer to say that for the magician, the physical bodies of the planets are merely one manifestation of their power. Even if we had a different solar system, our experiences would still fall into these seven realms. We’d just not be able to use astrology to discuss them.

The moon isn’t a planet according to scientific classifications, but those classifications are arbitrary, as those of us who still have Pluto in our memory can attest (I’m mostly annoyed that they ruined my perfectly good mnemonic for the planets: My very educated mother just served us nine pizzas. Now what is she going to serve us? Noodles?). For astrologers and magicians, a planet is merely a thing visible from Earth that moves across the sky in the ecliptic, the plain cut across the sphere of the heavens by the movement of the sun and moon. The moon, being the fastest of these moving objects and also the most changeable, is therefore the icon of change and speed. It’s also large in the sky, roughly the size of the solar disk, and therefore represents the complement of the sun. It is visible both during the day and at night, but is the most impressive at night, and therefore represents those activities done at night: sleeping, dreaming, and sex.

Mercury isn’t as fast or changeable as the moon, but it does have its phases and, because it orbits the sun faster than the Earth, we often observe it seeming to go backwards as it laps us. Other planets do this as well, but Mercury does it frequently, and therefore the ancients named this planet after the god who in Roman mythology acted as messenger of the gods. Mercury was also the gods of merchants, so that metaphoric association comes along with it as well, but overall Mercury represents the human activities of communication and thought. Mercury also represents technology, especially communication and travel technologies. Some people claim to experience more breakdowns in these types of devices during times of Mercury’s retrograde (or backwards) motion, but I’m not sure if this is true or not. It may be a case of confirmation bias.

Venus is bright and has a milky white color when seen away from city lights. Like the other inner planets, it closely attends the sun, rising just before it or setting just after, and therefore it has been known as both the morning star and the evening star. The Greek name for the planet, Phosphorus, was later given to a flammable metal because it means “light bearer.” The Latin calque of this word, lucifer, was used to describe both Christ and Satan, at different times. The Romans, however, identified this planet as Venus, their goddess of love, because of its brightness and beauty. For this reason, Venus rules over love, pleasure, sex, and beauty.

Mars, on the other hand, is named after the Roman god of war, or at least so everyone says. But Mars or Mavors was more than just the god of war to the Romans: he was the god of agriculture, civilization, honor, duty, and war. In other words, he was (well, is) the god of labor of all types, whether violent or not. Similarly, the planet does not just rule violence and discord, but also energy and force. The red color of Mars is caused by iron in the soil of the planet, an occasion where occultists hit it right before scientists did, as iron is the mineral ruled by Mars.

Sol, or the sun, was central to astrologers even before we developed the model of a heliocentric universe. The sun represents health, identity, ego, selfhood, honors, and creativity. How much of these associations are modern is difficult to determine. The ancient Romans and Greeks didn’t have the same concept of ego that we have, nor would they regard selfhood as an unmitigated good as many Americans might. In Vedic astrology or Jyotish, the sun is not benevolent, as it can destroy the power of any planet near it, as well as indicate areas of potential problems if badly aspected. We sometimes forget that Apollo, the beautiful healer of ancient Greek mythology, was also the bringer of plague.

Jupiter, named after the Roman god Iuppiter, is a slow-moving and distant planet, which was early associated with the power and justice of its namesake god. In another interesting parallel of astrology and astronomy, astronomers later discovered that the physical Jupiter is extremely large and its considerable gravity well has captured an abundance of moons (sixty-seven, by last count). In that respect, it is indeed a lordly planet. In astrology, it represents power, justice, benevolence, and wealth.

Saturn, named after the Roman agricultural god Saturnus, governs systems and restrictions. Where Jupiter expands outward, Saturn pulls inward. For this reason, Saturn is sometimes regarded as a figure of malice in astrology, but just like the violent energy of Mars, the restrictions of Saturn placed in their appropriate place can be beneficial. Saturn is sometimes marked with the keywords of “contraction” or “restriction,” but you can also think of it as crystallization or organization. Saturn is the planet of patterns and procedures, rules and laws, both in the sense of human laws and laws of nature.

As an aside, when I flip open an occult book asking myself if I want to buy it, I hate seeing a long list of definitions of things I already know. I know that some of my readers may be new to this symbolism, and some are now going, “Aw, darn it, astrology? Please.” And others are making impatient “hurry up” motions in their minds. I sympathize, but the above list isn’t just an introduction to the idea of each of the symbols: it illustrates my larger point, which is that all of human experience can be divided up into these categories, and we already do so whether we are familiar with astrological symbolism or not.

Here are four experiences: falling in love, seeing a beautiful painting, getting arrested, buying a new car. If we try to look at these experiences as material events, trying as best we can to eschew symbolism, we can see that they are all unrelated. But if you were to ask people which two are the most alike, most people would probably place falling in love and seeing a beautiful painting closer together than getting arrested or buying a car. You might get the occasional poet who regards love as a kind of prison, or the car aficionado who thinks getting a new car is a lot like love. But overall, most people regard love and beauty as related experiences. They already, without necessarily knowing the terms, lump them under Venus.

But if we’re trying to come up with a set of symbols that can communicate human experience, we still need to account for that car collector or that cynical poet. How do we do that? We recognize that the domains of the planets interact and overlap. For example, you can mix the influences of Saturn and Venus in such as a way as to create a sense of love as imprisonment. You can also add the influence of Jupiter (and perhaps Mercury) to Venus to create a love for automobiles. In astrology, there are multiple ways such influence can derive, but this isn’t a book on astrology so I will not go into extreme detail, as much as I might like to.

Instead, I want to once again call your attention to the Fludd drawing of the Mirror of Nature. The concentric rings in the center represent the orbits of the planets. You can see that these concentric rings spread out from a center point, and that several of the planets have lines connecting them to items in lower concentric rings. Renaissance magicians saw each planet not only potentially interacting with each other, but with the elements as well. It’s common to speak of the planets sending out “rays,” but one should be careful not to assume this description is necessarily physical. Although I’m sure some Renaissance magicians believed that literal rays emanated from the actual physical body of Mars, others recognized, I think, that the physical body of Mars is just the manifestation of the ray of something else—an Ideal Mars, if you will.

While we’re on Mars, let’s imagine that Mars sends a ray down through the concentric rings. In the world of matter, it manifests through the elements. In alchemy, we’d recognize Mars in Earth as iron, and Mars in water as Oil of Vitriol (what we now call sulfuric acid). We’d also recognize that Mars arises in the mental analogues of those elements. Mars in earth is the physical energy of the body; Mars in air is the strife of the mind; Mars in water is anger, and so on. It’s not always immediately obvious which thing a given planet manifests as in a given element. Yet it’s valuable to meditate on the possible permutations, both to familiarize yourself with the symbols and to begin to understand experience from a magical perspective. Keep in mind that meaning is the interaction of symbols in a mind.

The entire process is complicated by the fact that multiple rays may affect mixtures of elements. At this point, an attempt to tabulate the possible permutations becomes tempting but impossible. One would end up with a thesaurus of every possible experience, a work of endless labor and dubious value. However, if someone created such a thesaurus with detached pages, in such a way as they could arrange the basic combinations in endless other combinations, the labor might be reduced considerably. Moreover, such a book could be “read” by interpreting the relationships on the fly, instead of imagining ahead of time every single possible combination.

Most systems of divination are just that. They have tokens—in our case here, cards—that represent particular arrangements of elements. In astrology, for example, the seven planets move through twelve houses and twelve signs, each of which is composed of the key of four permuted through the key of three—so that, for example, you have fixed fire (Leo), mutable fire (Sagittarius), and so on.

Once you start looking, you begin to see these symbolic patterns everywhere—and this means that nearly anything can become a medium for communication with the Anima Mundi. When the magicians of the eighteenth-century occult revival stumbled across a popular card game that involved evocatively decorated cards, they immediately noticed patterns of symbolism that hinted to them that this system was something more than a card game. They began to modify the cards. Eliphas Levi went so far as to perform a wholesale editing of the symbolism, creating just such a thesaurus as mentioned earlier. Later decks, such as the Rider-Waite and the Crowley Thoth Tarot carried this process even further.

Was the tarot really a secret occult book hidden in the form of an innocuous card game? Maybe, although I am skeptical. It doesn’t matter—even if humans intended only to make a fun game to pass a few hours, the Anima Mundi is always whispering to us in our unconscious, and so we may very well have created the cards, all unknowingly, to reflect her subtle language of symbols. In the next chapter, we’ll explore how this cosmology or understanding of the universe can help us use cards to understand the mind of the world.

11. Henry Cornelius Agrippa, Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Donald Tyson. (Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn, 2007), 27.