IN THE DAYS when the judges ruled, there was a famine in the land, and a man from Bethlehem in Judah, together with his wife and two sons, went to live for a while in the country of Moab. 2The man’s name was Elimelech, his wife’s name Naomi, and the names of his two sons were Mahlon and Kilion. They were Ephrathites from Bethlehem, Judah. And they went to Moab and lived there.

3Now Elimelech, Naomi’s husband, died, and she was left with her two sons. 4They married Moabite women, one named Orpah and the other Ruth. After they had lived there about ten years, 5both Mahlon and Kilion also died, and Naomi was left without her two sons and her husband.

6When she heard in Moab that the LORD had come to the aid of his people by providing food for them, Naomi and her daughters-in-law prepared to return home from there.

7With her two daughters-in-law she left the place where she had been living and set out on the road that would take them back to the land of Judah.

8Then Naomi said to her two daughters-in-law, “Go back, each of you, to your mother’s home. May the LORD show kindness to you, as you have shown to your dead and to me. 9May the LORD grant that each of you will find rest in the home of another husband.”

Then she kissed them and they wept aloud 10and said to her, “We will go back with you to your people.”

11But Naomi said, “Return home, my daughters. Why would you come with me? Am I going to have any more sons, who could become your husbands? 12Return home, my daughters; I am too old to have another husband. Even if I thought there was still hope for me—even if I had a husband tonight and then gave birth to sons—13would you wait until they grew up? Would you remain unmarried for them? No, my daughters. It is more bitter for me than for you, because the LORD’s hand has gone out against me!”

14At this they wept again. Then Orpah kissed her mother-in-law good-by, but Ruth clung to her.

15“Look,” said Naomi, “your sister-in-law is going back to her people and her gods. Go back with her.”

16But Ruth replied, “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. 17Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the LORD deal with me, be it ever so severely, if anything but death separates you and me.” 18When Naomi realized that Ruth was determined to go with her, she stopped urging her.

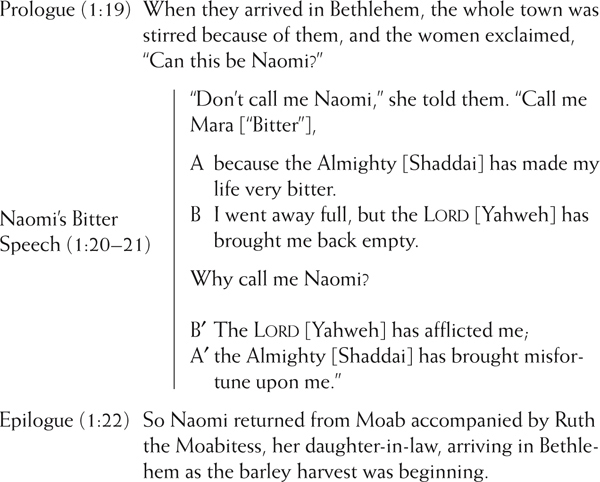

19So the two women went on until they came to Bethlehem. When they arrived in Bethlehem, the whole town was stirred because of them, and the women exclaimed, “Can this be Naomi?”

20“Don’t call me Naomi,” she told them. “Call me Mara, because the Almighty has made my life very bitter. 21I went away full, but the LORD has brought me back empty. Why call me Naomi? The LORD has afflicted me; the Almighty has brought misfortune upon me.”

22So Naomi returned from Moab accompanied by Ruth the Moabitess, her daughter-in-law, arriving in Bethlehem as the barley harvest was beginning.

Original Meaning

RUTH 1:1–6 SERVES as a prologue to this edifying short story; what follows in 1:7–22 is Act 1. Naomi is the key person in this act. In the following chapters, Ruth, Naomi, and Boaz take the initiative in chapters 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

The Prologue (1:1–6)

THIS PROLOGUE PROVIDES the setting and predicament that will dominate the book: Since the Judahite males of the family of Naomi die while living in Moab, she is without a male to care for her. In staccato style, the story compresses a number of years into a few verses in order to confront the reader with the book’s main problem: Naomi’s emptiness. The prologue divides into three subsections.1

The setting (1:1–2). The story is set in the period of the judges (1:1a). Such an allusion must have conjured up for the original audience visions of the moral and spiritual declivity with the consequent oppressions and chaos that prevailed in that time.2 In identifying the story with the period before the monarchy, a period that the book of Judges depicts as a rough and violent era, the book of Ruth offers a significant contrast, for it presents a serene and pastoral picture. This opening clause forms an inclusio with the historical reference to David in 4:17b so that the leadership vacuum evident during the period of the judges is answered in the ideal king, David.3

Verse 1 quickly adds that “there was a famine [rāʿāb] in the land, and a man from Bethlehem in Judah . . . went to live for a while [lit., to live as a foreigner, gûr] in the country of Moab.” Since “there was a famine in the land” occurs elsewhere only in Genesis 12:10 and 26:1,4 this phrase clearly alludes to the famines of the patriarchs: Abram, who left the land to live as an foreigner (gûr) in Egypt, and Isaac, who left the land to live (gûr) in Gerar among the Philistines. In both of these instances, in spite of the tragic famines and patriarchs’ false witnesses concerning their wives, Yahweh’s sovereign plan brought blessing on his people. The text infers this may happen again here.

Bush remarks concerning this famine during the period of the judges:

There is not the faintest suggestion that the famine is Israel’s punishment for her sin. Especially there is not the slightest hint that the tragic deaths of Elimelech and his sons in any way resulted from their having forsaken their people in a time of trouble or their having moved to Moab where the sons married Moabite women. Later rabbinic exegesis used such themes of retribution and punishment to the full, but they are read into the story, not out of it.5

There is no doubt that rabbinic excesses should be avoided at all cost, but the tendency among recent commentators to interpret the famine, the move to Moab, and the subsequent deaths as nothing other than matter-of-fact items6 seems to miss the implication of the first two statements in verse 1.

Even a cursory knowledge of the Deuteronomic blessings and curses and the general moral degeneracy of the period of the judges raises the interpretive expectations here. The argument that the Deuteronomic passages are later and therefore irrelevant to the interpretation of Ruth 1:1 does not hold since the date of Ruth may not be as early as some scholars have argued.7 Even if the famine is not the result of drought (which most interpreters innately presume) but of the military destructions during the period of the judges, this too still has its inherent connections to the Deuteronomic covenant’s blessings and curses section.8 Finally, the very mention of the period of the judges before the mention of the famine means that the story of Ruth is not a completely self-contained literary piece. The reader (and originally hearers) must fill in the narrative gaps here. Moreover, the literary links with Genesis 12 and 26 demand a fuller reading.

Although no such famine is recorded in the book of Judges, the canonical linkage presumably implies that the famine is the result of disobedience to Yahweh’s covenant, a disobedience pervasive during that era (Judg. 2:20). Deuteronomy 28:48 includes famine (rāʿāb) in the list of curses (cf. also Lev. 26; Deut. 28:16–24)9 that God would bring on the Israelites if they served other gods rather than him (which they did, cf. Judg. 2:10–19). The fact that there is famine in Israel and not in Moab10 is significant to the plot, not only in providing a context for the heroine to be a Moabitess rather than a Judahite so that the motif of ḥesed works,11 but for underscoring the overall negative portrayal of the situation that brings Naomi to her complete emptiness.

Ironically, the man comes from Bethlehem (bêt leḥem),12 which means “house of bread,” but there is no “bread/food” in that city. And this man, together with his wife and two sons, go to live as resident foreigners in the country of Moab—a traditional enemy of Israel throughout biblical history.13 As Hubbard aptly notes:

This family left the familiar for the unfamiliar, the known for the unknown. The foursome was legally a “stranger” (Heb. gēr), and so was its world. Further, to seek refuge in Moab . . . was both shameful and dangerous.14

Such a move to the territory of Moab is not outside the plausible, since there are occasions even in modern times when more rain falls in southern Moab than in Bethlehem.15 The specification of Judah in connection with Bethlehem is necessary since there was another city with the same name in Zebulun (Josh. 19:15). The narrator gives the reader the impression that out of all the Bethlehemites caught up in this famine, only this man and his family seek refuge in the “country” (śādeh) of Moab. The term śādeh is an “arable, cultivatable land or field.” Later the reader discovers that ironically this man “alienated” a śādeh in Bethlehem in order to go sojourn in a śādeh in Moab.

Verse 2 relates that the man’s name is Elimelech (“My God is king”) and his wife’s name is Naomi (derived from the root nʿm [beautiful, pleasant, good]).16 The meanings of both names play a role in the story: Elimelech with the coda, Naomi with 1:20. The names of their two sons are Mahlon and Kilion. Both names are etymologically uncertain and presently unattested in the ancient Near Eastern onomastica.17 They may be coined names meaning “sickly one, sickness” and “finished or spent one, [hence] destroyed, death” used as “ominous names,”18 implicitly pointing to the intensification of the crisis about to strike Naomi.19

The mention in verse 2 that the foursome were Ephrathites from Bethlehem Judah is significant to the development of the story. It seems very probable that the “clan” (mišpāḥâ) of the Ephrathites (the clan of which Elimelech and Boaz were part) was only a subsection of larger Bethlehem population. If the entire population of Bethlehem derived from one mišpāḥâ or part of a still more widely dispersed mišpāḥâ, then the singling out of Boaz as “known kinsman” of the same clan as Elimelech is foolish. If all Bethlehemites were from the same clan as Elimelech, then all Bethlehemites would have been “known kinsmen” of Elimelech. The excitement and suspense of the story depends on the fact that only some Bethlehemites are of Elimelech’s mišpāḥâ.20

Verses 1–2 describe the setting, the characters, and the initial circumstances of the book. They are framed by the contrast between “went . . . from Bethlehem in Judah” in verse 1 and the summary statement at the end of verse 2: “They went to Moab and lived there.”21

Double bereavement (1:3–5). The family’s double bereavement is powerfully conveyed, which forms a chiasm with an identically parallel inclusio (lit. trans.):22

A Then died Elimelech, the husband of Naomi, and she was left alone with her two sons.

B They took Moabite wives, the name of one Orpah and the other Ruth,

B′ And they lived there about ten years.

A′ Then died also both Mahlon and Kilion, and the woman was left alone without her two boys and without her husband.

The writer’s terse, staccato style adds to the disaster of the double deaths and the resultant “aloneness” of Naomi. Although tragic is the loss of her husband, Naomi’s aloneness is mitigated by the fact that her two sons are alive. As Hubbard notes, the sons’ marriages must have fanned Naomi’s flickering hope into brighter flame,23 although the text does not offer an evaluation of these marriages to Moabite women. In fact, the narrator does not specify who married Orpah24 and who married Ruth.25 Does he approve or disapprove of these marriages or does he not care?

Marriages to the people of the land (i.e., Canaanites) were strictly forbidden (Deut. 7:3; cf. Judg. 3:6). Deuteronomy 23:3[4] does not prohibit marriages to Moabites and Ammonites; it only prohibits that the offspring of such unions from entering the assembly of the Lord until the “tenth” generation.26 Ironically, the marriages of Mahlon and Kilion lasted ten years, until their deaths. Both marriages, however, are marked by infertility: ten years, but no children (1:4). The covenantal implications are clear: As Yahweh withheld the rain and thus produced the famine, so he withheld fertility, hence no children (Deut. 28:4, 18; cf. 1 Sam. 2:5–6).

Although the sons die after a ten-year period,27 the story compresses this time interval. The narrator creates the impression that Naomi is left battered by the relentless onslaught of one tragic event after another (cf. the battering of Job, Job 1:6–2:10).28 But this second bereavement is overwhelming for Naomi. She has lost her children (1:5; cf. the play on the word yeled in the epilogue, 4:16). Now there is only “aloneness” without any mitigation, since she is alone “without her two boys and her husband.” The author focuses on Naomi’s emptiness and misery.

The family of Elimelech teeters on annihilation. Thus, while the threat of starvation plays a large role in the story (1:1, 6, 22; ch. 2; 3:15, 17), it is only secondary to the problem of the family’s survival. In ancient Israel, the loss of a family from existence was a great tragedy. When a family died out physically, it ceased to exist metaphysically. That robbed Israel of one of her most prized possessions, namely, clan and tribal solidarity.

Hubbard points out that another crisis is the possibility that Naomi now faces old age without anyone to care for her.29 As a widow, Naomi lacks the provision and protection of a husband in the male-dominated ancient Near East. Moreover, it must be remembered that she lives in a foreign land. Because of her age and poverty, she is effectively cut off from the three options that might normally be open to a widow:30

1. There was the possibility of returning to the house of her father. But her parents are most likely already dead. If the disaster had come earlier in life, she could have returned to her father’s house like an ordinary young widow. But this is not the case here.

2. There was the possibility of remarriage, perhaps even a levirate marriage (Deut. 25:5–10). But this seems to be out of the question since she is beyond child-bearing years.

3. There was the possibility of supporting herself through some kind of craft or trade. But this is unlikely since she has none (the vast majority of women in antiquity did not have such an option).31

Furthermore, she is an old widow without children—the worst fate that an Israelite woman might experience. “She faces her declining years with no children to care for her and no grandchildren to cheer her spirits.”32 Naomi is a stranger in a foreign land—a victim of death and of life.33

Hint of change (1:6). Through these initial verses of the story, the introduction has set the stage by showing that all possible lines of ḥesed in the ancient world available to Naomi have been effectively severed. But verse 6 gives a hint that this may change if empty Naomi returns to the newly filled land of promise since Yahweh has come to the aid of his people, providing food for them. Verse 6 is antithetically parallel to verse 1, providing a chiastic contrast in content:34

A “there was a famine”

B “went to . . . Moab”

B′ “return . . . from there [lit., Moab]”

A′ “the LORD . . . [provided] food”35

Thus verse 6 rounds off and brings to a conclusion the prologue of verses 1–2 by balancing “went to Moab” :: “returned from Moab,” and “famine” :: “food.”36 This is the first time Yahweh is mentioned in the story, and it is in the context of his compassionate provision for his people.37 The language of verse 6 is also rich with assonance and alliteration (lātēt lāhem lāḥem), ending with the word for food (leḥem), which unsubtly directs Naomi, as well as the reader, back to Bethleḥem, “(store) house of bread/food.” As Yahweh has provided food for his people, will he yet provide fertility to Ruth and an offspring for Naomi? Finally, verse 6 also acts as a transition and a preview to what follows. It accomplishes this through the use of the key word šûb (return).38

Act 1: Naomi’s Return (1:7–22)

ACT 1 (1:7–22) is comprised of two scenes: Scene 1: Naomi and her daughters-in-law on the road to Judah (1:7–19a), and Scene 2: Naomi and Ruth arrive at Bethlehem (1:19b–22). The opening line intimates the development of this act, and the closing sentence serves as transition to what follows in Act 2. The section emphasizes the responsibilities inherent in the ties of kinship—in particular, to the elderly widow (i.e., the past).

Scene 1: Naomi and her daughters-in-law on the road to Judah (1:6–19a). No longer does the writer convey the story through the terse, staccato style of the prologue. Rather, he now relates certain incidents in considerable detail; indeed, in this scene he brings the action to a full halt partway on the journey home and relates to us an extended conversation between Naomi and the two young Moabite widows. Moreover, he utilizes his favorite literary device here as well as in the rest of the book: dialogue. More than half the book is in dialogue (55 verses out of 85). In three separate dialogues, Naomi urges her daughters-in-law to “go back” (šûb) to their Moabite people and leave her (secs. B, D, and B′, 1:8, 11, 15). The section appears to be chiastic in structure.39

A Narrative introduction: Naomi and daughters-in-law “leave” (yṣʾ ) and begin to go (hlk) to the land of Judah (1:7)

B Dialogue 1: Naomi urges the women to return home (1:8–9a)

C Narrative transition: kissing good-bye and weeping loudly; Naomi kisses them (1:9b)

D Dialogue 2: The young women refuse, insisting that they go with her; Naomi impassionately urges them again to return home (1:10–13)

C′ Narrative transition: weeping loudly and kissing goodbye. They continue weeping, Orpah kisses Naomi good-bye, but Ruth clings to her (1:14)

B′ Dialogue 3: Naomi urges Ruth to follow Orpah’s example and return home; Ruth refuses and impassionately reaffirms her commitment to Naomi (1:15–18)

A′ Narrative conclusion: Naomi and Ruth travel (hlk) and arrive (bwʾ ) at Bethlehem (1:19a)

In section A (1:7), the three women leave Moab and head for the land of Judah. The terms “leave” (yṣʾ ) and “go” (hlk) correspond and contrast to section A′ (1:19a), where Naomi and Ruth “go” (hlk) and “come” (bwʾ ) to Bethlehem.

In Section B (1:8–9a), the first dialogue of the book, Naomi urges her daughters-in-law to return “each of you, to your mother’s home.” Having come to Moab as a foreigner, Naomi certainly understands the problems and difficulties her daughters-in-law will face if they accompany her back to Bethlehem. She intends to spare them such grief. The phrase “mother’s house/home” is unusual, since most often the Hebrew Bible refers to a widow returning to her father’s house. While many different explanations have been given, the emphasis here seems to be on the contrast Naomi wishes to make—a widow should return to her mother and not stay with her mother-in-law.40

Naomi’s urging must have been with some mixed feelings. To urge Orpah and Ruth to return to Moab necessitates that she will travel home completely alone. But to have them return to Judah with her requires them to renounce all hope and effectively consign them to the life of a poor old widow. Thus she sees no other choice but to encourage them to return. To the calamity of losing home, husband, and sons, she must now add another, this one self-inflicted: She must return home alone.41

Naomi pronounces a blessing on the women (1:8): “May the LORD show kindness [ḥesed] to you, as you have shown to your dead and to me.” Naomi invokes a proportionate blessing of ḥesed on the women because of their ḥesed to the deceased (see the discussion of ḥesed in the introduction). As the women have shown covenantal loyalty, kindness, goodness, mercy, love, and compassion in voluntary acts of extraordinary mercy or generosity toward Naomi and her two sons, so Yahweh will show ḥesed to them. The reference to the dead is simply Naomi’s way of referring to her two sons, to whom Ruth and Orpah have shown loyalty and faithfulness during the ten years of their marriages. Naomi concludes with an additional blessing: “May the LORD grant that each of you will find rest [repose, menûḥâ] in the home of another husband.” She recognizes that in the world in which they live, security and well-being are dependent on a link with some male.

In section C (1:9b), Naomi kisses her daughters-in-law good-by, and they all weep loudly. The verb nšq can mean simply “to kiss,” but it is also used as a gesture of farewell (cf. Gen. 31:28; 1 Kings 19:20). It is clear that all three weep. This pattern of kissing plus weeping will be inverted below in C′.

Section D (1:10–13) is the second dialogue and the pivotal point in Scene 1 of Act 1. The young women refuse to leave Naomi alone, insisting that they will go with her: “We will go back with you to your people” (1:10). But Naomi impassionately urges them again to return home. She does this through three distinct dialogue units (vv. 11, 12–13a, 13b), which consist of carefully balanced couplets.42 These are ordered in intensity, climaxing in the final clause: “The LORD’s hand has gone out against me!”

(1) The first dialogue unit (1:11) contains a pair of rhetorical questions:

Return home [šûb], my daughters!

Why would you come with me?

Am I going to have any more sons, who could become your husbands?

Naomi is not eliciting facts or seeking an explanation; she is expostulating.43 Her appeal is logical: Hope for a better future is not to be found with her. The probability of her having more sons is remote. Notice that Naomi does not argue: “Can I find you husbands?” Her logic is linked to the levirate marriage possibilities, as the next dialogue unit will explain.

(2) The next dialogue unit (1:12–13a) answers the initial rhetorical questions and then continues with a balanced conditional sentence that concludes with another pair of rhetorical questions, each pair introduced by the same Hebrew particle (lit. trans.):

Return home [šûb], my daughters! Go!

For [kî]44 I am too old to have a husband!

Even [kî] if I thought [or said] there was still hope for me—

even [gam] if I had a husband tonight

and then [wegam] (actually) gave birth to sons—

would [halāhēn] you wait until they grew up?

Would [halāhēn] you remain unmarried for them?

Naomi’s logic of this hypothetical scenario heightens the argument developed in the first dialogue unit, that is, the improbability of her having more sons. For in her hypothetical scenario of becoming pregnant with sons that very night (utterly impossible anyway, since she has no husband), logic again dictates that the two Moabite women would be foolish to wait for these sons to grow up in order to marry them (they would be elderly women themselves by that time). Hence, Naomi’s invocation to return to their families has even greater force of argument.

(3) The third dialogue unit contains a couplet that reaches an irrefutable conclusion by moving from the foolishness of the previous rhetorical questions to the statement of Yahweh’s past action. Again the same Hebrew particle introduces the pair of statements:

No, my daughters.

[For, kî]45 it is more bitter for me than for you,46

because [kî] the LORD’s hand has gone out against me!

Naomi concludes her argument with emphatic, climatic force with two statements that are meant to convince the two Moabite women not to stick with her. Things are far worse in her state than theirs. To stick with her is to doom oneself to her fate. And this is a fate that the hand of the God of Israel, Yahweh, has brought against her.47 Thus to stick with her is to put oneself in the same situation in which Yahweh will be against that person. To be connected to a person who has God opposed to them is a situation that few would desire. One ought to shun such a person to escape the maelstrom of her misfortune. What better argument to make return to Moab attractive? Naomi has built an airtight case for not being connected to her.

While the text has only subtly alluded to this fact and the reader may not have fully recognized it, Naomi makes it abundantly clear that, at least in her understanding, the earlier famine in Bethlehem, her family’s sojourn in Moab, the deaths of her husband and sons, and the barrenness of her daughters-in-law are all evidences of God’s hand as the cause of her hardships. She feels she is the target of God’s overwhelming power and wrath. That God is actively behind these events will be affirmed throughout the story; that he is punishing Naomi—at least as Naomi feels is the case—is not necessarily correct. God is not “out to get her” (see further comments below).

In section C′ (1:14), there is an inversion of the action of section C (weeping + kissing). They all weep loudly once again. This weeping indicates the women’s concurrence with Naomi: The only sensible course of action is to leave Naomi and return to Moab.

Consequently, Orpah kisses Naomi good-bye. Naomi’s powerful argument has convinced her that a normal life back in Moab is preferable to life with Naomi in Israel. She chooses the “sensible” track. But this only heightens Ruth’s reaction. She clings (dbq) to Naomi. The order of the clauses expresses the simultaneity of Ruth’s and Orpah’s actions as a contrast between them. The expression “cling to” (dbq) + prep. b) implies firm loyalty and deep affection. It implies leaving membership in one group to join another. In Genesis 2:24 this expression is used along with its opposite (ʿzb):

For this reason a man will leave [ʿzb] his father and mother,

and be united [cling, dbq + b] to his wife

and they will become one flesh.

Thus Ruth’s gesture illustrates her commitment to “abandon” (ʿzb) her Moabite father’s house and permanently remain with or cling to (dbq + b) Naomi.

While Orpah serves as a foil to Ruth in the story heightening the contrast, the narrator does not criticize Orpah’s decision. She is not portrayed negatively, the reader is given good reason for her decision and little other information. It is not that Ruth is right and Orpah is wrong per se. Rather, the actions of Orpah make Ruth appear that much more the positive (the unnamed nearer kinsman-redeemer will serve the same function in relation to Boaz in ch. 4). Berlin puts it this way:

In the case of Orpah, both she and Ruth initially react the same way, expressing reluctance to leave Naomi. Only after prolonged convincing does Orpah take her leave, and, of course, Ruth’s determination to remain with Naomi becomes, in the eyes of the reader, all the more heroic. The two were first made to appear similar—they were both Moabite wives of brothers, both childless widows, both loyal to their mother-in-law. Only gradually is the difference between them developed, and when it is, the effect is dramatic and moving.48

Section B′ (1:15–18) contains the third dialogue. Naomi urges Ruth to follow Orpah’s example and return home: “Look [hinnēh] . . . your sister-in-law [yebēmet is going back to her people and her gods [ʾ elōhêhâ].49 Go back with her [lit., sister-in-law, yebāmâ].” The term yebēmet is connected with the levirate marriage (see Deut. 25:7–9). Since the word ʾ elōhîm can be understood as a “plural of majesty,” a number of commentators opt for a singular sense so that the word refers to Chemosh, the national god of the Moabites. Actually, the context leaves this open so that the term may refer to Chemosh (sing.) or to the numerous deities worshiped in that country (plural). In either case, the contrast is consequently heightened with Ruth’s words that her spiritual commitment is to the God of Israel.

Ruth refuses to go back and impassionately reaffirms her commitment to Naomi. There is a chiastic structure to her affirmation speech (lit. trans. of 1:16–17):

a Do not press/urge me to leave you,

or to turn back from following you.

b For wherever you go, I will go;

And wherever you stay, I will stay.

c Your people will be my people,

And your God, my God.

b′ Where you die, I will die;

And there shall I be buried.

a′ Thus may Yahweh do to me and more so—

Nothing but death will separate me from you!

The terms in b, “go” (hlk) and “stay” (lwn), are opposites, creating a merism, equivalent to saying “all of life.”50 Ruth swears her commitment to Naomi in the name of Israel’s God, thus acknowledging him as her God.

In the conclusion to her speech of affirmation (1:17b), Ruth uses a self-imprecatory oath formula. There is a difference of opinion regarding how this phrase should be translated. The following are the three possibilities:

if anything but death separates you and me (NIV)

if even death separates you and me (RSV; Campbell, Ruth, 74–75;

Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 119–20)

nothing but death will separate me from you (Bush, Ruth, Esther, 82–83)

Whatever the case, the essence of the oath is that only death will separate Ruth from Naomi. Her commitment to Naomi transcends even the bonds of racial origin and national religion: Naomi’s people and Naomi’s God will henceforth be hers. With such a speech of affirmation, Naomi realizes that Ruth is determined51 to go with her, so she stops urging her to leave and go back to Moab. All the power of Naomi’s logic and argument has been ineffective. Ruth’s faith defies human logic and wisdom.52

Section A′ (1:19a) contains the narrative conclusion: Naomi and Ruth go on (hlk) until they come (bwʾ ) to Bethlehem. Thus Scene 1 ends.

Scene 2: Naomi and Ruth arrive at Bethlehem (1:19b–22). This scene describes the arrival of Naomi and Ruth in Bethlehem and the interaction between the women of Bethlehem and Naomi. This is presented by the narrator in dialogue that Naomi once again predominates. The first clause of the scene (“When they arrived [bwʾ ] in Bethlehem”) not only repeats the information of 1:19a (“until they came [bwʾ ] to Bethlehem,”), but forms an inclusio with the closing statement of Act 1, “arriving [bwʾ ] in Bethlehem” (1:22b).

This closing statement of 1:22 emphasizes the return in the context of the “barley harvest,” which confirms the statement in 1:6 that Yahweh has provided food for his people and brings resolution to the famine mentioned at the beginning of the prologue (1:1). While providing closure for Act 1, this mention of “the barley harvest” links with and previews Act 2, in which Ruth gleans in the fields of this same harvest.

As in Scene 1, the narrator prefers dialogue rather than narrative to communicate his message. This entire passage consists simply of the dialogue between Naomi and the women of Bethlehem (1:19b2–21) with a narrative statement at the beginning (1:19b1) and at the end (1:22). Thus the structure of the scene appears to be:

The scene opens with the glad reception of the women of Bethlehem for Naomi (“the whole town was stirred53 because of them”). The question “Can this be Naomi?” is not addressed by the women to Naomi but rather to one another, creating excited commotion. It is a rhetorical question having the force of an exclamation.54

This question of the women is followed by Naomi’s sarcastic double response, in which she utilizes two wordplays on her name, the first in the form of a command and the second in the form of a question. In the first wordplay (1:20), she denies the meaning of her name, demanding that she be called Mara, “Bitter” (mārāʾ comes from the root mārar, “to be bitter”), instead of the antonym “Naomi” (“pleasant, beautiful, good”).55 In the second wordplay (1:21b1), she employs a rhetorical question (“why”) that is intended to reject the identity that her name implies.

Both wordplays give the twofold reasons for the denial of her name in the design of a couplet. The two couplets, in turn, form a chiasm A:B and B′:A′. A and A′ utilize the divine name “Shaddai”56 and are parallel in structure and content; B and B′ are parallel in their use of the divine name “Yahweh,” although they are different in structure and content.

In B, Naomi states (lit.): “Full was I when I went away; but empty has Yahweh brought me back.” The emphasis is clearly on full (mlʾh) and empty (ryqm). The two statements are chiastic.57 In B′, the expression ʿnh b means “to respond/speak against.” It is usually used in a juridical context, where it has the technical force “to testify against” (e.g., Ex. 20:16; Num. 35:30). The NIV’s “afflicted” attempts to capture this nuance. In Hebrew thought, one’s name was often understood to be expressive of one’s character, being, and personality. Thus, Naomi challenges the tone and content of the women’s glad and delighted cries by twice denying the meaning of her name.

In urging the women of Bethlehem to call her “Mara” (“Bitter”) “because the Almighty [Shaddai] has made my life very bitter [hēmar],”58 there is an interesting parallel in one of Job’s speeches in which he states:

As surely as God lives, who has denied me justice,

the Almighty [Shadday], who has made me taste bitterness [hēmar] of soul. (Job 27:2)

In addition, Naomi’s feeling that Yahweh is making her a target for his arrows is also paralleled by a feeling that Job expresses:

The arrows of the Almighty [Shadday] are in me,

my spirit drinks in their poison;

God’s terrors are marshaled against me. (Job 6:4)

Thus, “Naomi returned along with Ruth the Moabitess, her daughter-in-law—she who returned from the territory of Moab” (Ruth 1:22, lit.). By the structure of this sentence, the narrator gives Ruth’s “return” prominence.59 This is further heightened by the identification he gives her, using her full name “Ruth the Moabitess,” hence underlining her foreign origin.

Not only has Naomi returned home, so has Ruth. Naomi has returned home empty, unfulfilled, and bitter. Her journey has been a journey into the depths, and she can see nothing else. But there is more. In Naomi’s anguished response to the delighted cries of the women of Bethlehem—all absorbed in her own world of pain and bitter affliction—she fails even to acknowledge Ruth’s presence with her, a presence whose accomplishment transcends the call of religion and home and hope! Her whole complaint is voiced in the singular: “. . . bitter indeed has the Almighty made my life . . . empty has Yahweh brought me back . . . the Almighty has pronounced disaster upon me!” (1:20–21, lit.).

In a subtle touch of the narrator, Naomi utters her complaint as though Ruth, whose words of loving commitment still ring in the readers’ ears, has never pronounced these words at all! Yahweh has indeed not brought Naomi back empty, and the final word to this effect lies with the narrator when, in his closing summation, he gives all the prominence to describing Ruth’s arrival as a “return.”60 Thus, “we know that Naomi is not alone and will not be.”61

The last sentence of verse 22 is anticipatory of the means by which Yahweh will provide for the two widows: It’s the beginning of the barley harvest when they arrive in Bethlehem. The timing is providential (one more example of Yahweh’s sovereignty) for this means that the barley and wheat harvests are just beginning to take place (late April—early May by our calendars).

Bridging Contexts

YAHWEH AND HIS COVENANT. Large impersonal forces appear to control the beginning of this narrative: geography, history, meteorology—circumstances beyond human control. The narrative is specific when it mentions Bethlehem, within Israel’s sphere, and becomes diffuse when it speaks of the other world, Moab, where Judahites ought to have no business. The historical situation of the period of the judges dictates a time of political, religious, and social problems. And the circumstances of a famine in Judah, a situation outside human abilities to remedy (esp. in antiquity), mandate that only disaster can follow.

Moab, where the god Chemosh reigns (so to speak), may not be experiencing famine when Elimelech and his family seek shelter there, but its fields will eventually kill a father and his sons and render their wives sterile and widowed. But behind these “forces,” so to speak, is the God of circumstances and situations—Yahweh, Israel’s covenant-keeping God. He is equally as faithful in keeping his covenant with regard to its curses as he is with regard to its blessings.

During the period of the judges, the Israelites lacked faith in Yahweh and broke his covenant (Judg. 2:1–5, 10–23). As seen in Judges, God chastened his people in accordance with his promised curses. He expected his people to live according to his Word in the land he had given them and not go to go and live in another land when difficult times arose. This will was clearly revealed in his Word. Elimelech, like many Israelites of his day, lacked the faith to trust God in the midst of this famine. The move to Moab was highly unusual and was outside of God’s revealed will. Ironically, Elimelech parts with a field (śādeh) in Bethlehem, in the Promised Land, to live in the field (śādeh) of Moab. Furthermore, the marriages of his sons were outside of God’s revealed will for his people.

All of this brought disaster on the family of Elimelech and his sons. In addition, the infertility was no accident. In light of God’s covenant stipulations, this was not simply bad luck or fate. Thus, the outcomes of these tragedies were truly disastrous for Naomi. She suffered because of decisions that were not necessarily hers. Yet the same sovereign Lord has already begun a process whereby Naomi will not only survive but will be genealogically redeemed. He provides the stimulus to return to Bethlehem—Yahweh has given his people food (1:6).

God and the human situation. There are three human issues in the narration of the prologue that transcend time: aloneness, hopelessness in suffering,62 and the plight of old age. Not only does Naomi suffer loneliness, but that loneliness is intensified in this short background narrative. Such loneliness is not unique to Naomi’s situation in ancient Moab, nor is the double bereavement of husband and children. These, unfortunately, find modern analogues.

People in such a double tragedy often experience hopelessness. Feelings of helplessness and uncertainty are often overwhelming. Naomi, as many in similar contemporary settings, feels the anquish of having no one to help—no kinsman-redeemer—and no hope of seeing one on the horizon. There are no options. There are no alternative plans. No amount of brainstorming can come up with any options. Such feelings can be debilitating. The longer she stays in Moab, the more she feels the deep distress of these tragedies and the debilitating anxiety for the future. Yet, in the deepest distress, at just the right moment, Yahweh brings hope—even the faintest hint of an option: The famine in Bethlehem is over, so there is the possibility of provision there.

In Act 1, Naomi is the main character. Even though Ruth gives her great confession of faith and affirmation in Yahweh in this section of the book, Naomi is the focus of this chapter. She speaks more than Ruth, and it is her experience that the narrator depicts as central to the development of his plot. This in no way lessens Ruth’s confession; it simply puts it in its proper context.

As in the prologue, God’s sovereignty over the human situation is maintained throughout Act 1. In spite of the obvious emotional grief that is stirred up by Naomi’s departure from Moab, God is sovereignly at work moving her back to Bethlehem in order to bring blessing into her life once again. Naomi, quite naturally, does not see the move with this in mind. While she knows that Yahweh can bless, as she invokes his blessing on the two younger women, she sees only disaster for herself. Yet the move back to Bethlehem is the means by which Yahweh will bring blessing into the old widow’s life. God’s sovereign timing is alluded to in the final statement of chapter 1, which mentions that the widows arrive in Bethlehem at the beginning of the barley harvest—a providential coincidence!

Approaching life with human logic. In Act 1, Naomi appears logical and practical. There is no reason to stay in Moab: no husband, no sons, no land, no food, no hope, no future—and she is a foreigner! The return to Bethlehem is logical. At least there is the clan to fall back on; moreover, there is food there now, so perhaps she can survive. If she remains much longer in Moab, she certainly will not survive. God has shut the doors on living in Moab any longer; there really isn’t any other option.

Naomi also logically sees that it is best for her daughters-in-law to return to their families’ homes. She blesses them, invoking Yahweh (twice) to show ḥesed and give them husbands.63 But both daughters-in-law initially respond with commitment to Naomi; they will go with her to Bethlehem.

Naomi responds with logic and practical wisdom. No more sons are coming from her! She is too old. Even if she were already remarried and could become pregnant that very night, logic argues against the women waiting for these hypothetical children to grow up—the women would be old ladies themselves by then. Besides—Naomi uses her most powerful argument—Yahweh is against her. Just look at the disasters! Anyone connected with her can expect the same—nothing but more cursing from Yahweh. So practical wisdom mandates that it is best to have no connection to her.

This time the logic and practical wisdom works, at least on Orpah. She returns to her family. But Ruth clings to Naomi (1:14). The narrator really does not have to relate the speech of faith and commitment of Ruth in 1:15–16. The verb “cling” already communicates Ruth’s abandonment of her father and mother, her country, and her country’s god/gods. She is completely committed to Naomi. Interestingly, the very logic and practical wisdom that has driven Naomi to her decision to return to Bethlehem—the means by which the sovereign Lord intends to bring blessing back into her life—if applied completely here, will eliminate the very means by which God intends to bring the blessing back into her life. If she returns alone, the means of God’s blessing will be effectively removed.

Nevertheless, Naomi (who cannot begin to perceive this means of restoration and blessing) still urges Ruth to return since Orpah has gone back. Fortunately, the narrator reports Ruth’s speech (1:16–17). Orpah serves as a foil to Ruth in the action of her return to her family. What ḥesed this Ruth has toward Naomi! Not only is Orpah a foil in action, but Naomi is a foil in word. Naomi’s logic is incontrovertible: There is only more disaster if Ruth continues with her. Yahweh is against her, so Yahweh will be against Ruth too. But rather than leave (as logic and practical wisdom would dictate), Ruth commits herself to this God of Israel.

Ruth is willing to accept whatever Yahweh may grant to Naomi and herself. Yahweh will be her God. Nothing but death will separate her from Naomi. Ruth was utterly determined to go with Naomi. It was her firm resolution. What ḥesed this Ruth has toward Naomi! It is truly ironic that it is the Moabite widow, Ruth—who like Naomi has lost her husband—who evinces this kind of commitment to Yahweh rather than the Israelite widow.

Naomi continues in her logic. She stops trying to convince Ruth to return. Why waste any more time and energy when someone is determined to do what she is going to do? Thus she (and Ruth) return to Bethlehem.

Naomi’s reaction to the women of Bethlehem is also logical. To the women’s innocent question of amazement that Naomi has returned, she challenges the tone and content of their delighted cries by twice denying the meaning of her name. Logic dictates that she was misnamed. What she has experienced mandates a name like Mara (bitter), not Naomi (pleasant). What Yahweh has done to her prescribes that her name be changed.

Finally, it is worth noting in this context that the opposite of Naomi’s logic is not illogic or emotion. It is Ruth’s determined commitment.

Reading Naomi’s character. In general, recent commentators have been much harsher on the character of Naomi than earlier commentators. For example, Fewell and Gunn paint a picture of a rather reprehensible Naomi. To them, Naomi’s silent response to Ruth’s magnificent speech of commitment in 1:16–17 is an indication of her hardenness of heart toward Ruth. They state: “If Ruth’s famous ‘Where you go, I go; your god, my god’ speech can melt the hearts of a myriad of preachers and congregations down the centuries, why not Naomi’s heart?”64

Recent commentators are equally hard on Naomi for other silences—for example, for her failure to so much as acknowledge Ruth’s presence to the women in Bethlehem as she rails against God at the end of chapter 1. Their reason for her behavior thus far is that she has got a Moabite “albatross” around her neck, whom she does not really want. Self-centered, resentful, bitter, and prejudiced, she certainly is no paragon.

While Naomi is human, with all the frailties that means, it seems to me that Fewell and Gunn have overread the narrative silences to paint a character who is far worse than the text intends to paint. This widow has gone through the awful experience of burying her husband and both of her sons in a foreign land and understandably has virtually no hope for survival. Cut her some slack! But if, for a moment, we grant Fewell and Gunn’s interpretation for the sake of argument, such an understanding of the person of Naomi makes Yahweh’s sovereign and providential ḥesed look that much greater as an act of grace toward a very undeserving widow.

However, it seems better to understand that Naomi is not evidencing little faith; rather, with the freedom of faith that ascribes full sovereignty to God, she takes God so seriously that, with Job and Jeremiah (and even Abraham, Gen. 15:2), she resolutely and openly voices her complaint. One should not minimize what this poor woman has gone through! The pain is real. Often it is commentators who have not experienced the kind of devastation and grief that Naomi experienced who sit in judgment.

The pain and anxiety, however, have indeed blurred her perception. Like many of Job’s speeches, Naomi’s anguished, reactive speech to the women of Bethlehem demonstrates one of the unfortunate truths of suffering: In the midst of pain, there is often self-absorption. It is “my” pain. Her entire complaint is singular in its orientation: “Bitter has the Almighty [Shaddai] made my life; empty has Yahweh brought me back; the Almighty [Shaddai] has pronounced disaster upon me!” Such self-absorption in the midst of pain and affliction is understandable. Yet it always blinds a person from God’s greater plan and the small ways in which God may be working this plan out.

Thus, Naomi is blind to the evident presence of Ruth, who stands as an outright contradiction to her bitter words. God has not brought Naomi back completely empty. She has Ruth. Granted that is not the same as returning with her husband and sons and grandchildren. But it is better than returning completely and utterly alone (as Act 2 will demonstrate, for without Ruth Naomi may have starved to death in a very short time).

A common misuse of Ruth 1:16–17. Sometimes at weddings, one hears a song or a reading of this passage—presumably on behalf of the bride to the groom—where Ruth 1:16–17 is invoked as a description of the commitment of the bride to the groom. While the declaration “Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay,” and so on, may sound initially appropriate for a wedding, this is hardly the context of the passage in Ruth. Obviously, Ruth’s commitment to Naomi to follow the God of Israel has nothing whatsoever to do with the commitment of a bride to follow the religious and social leadings of her husband (on reflection, a rather shocking idea). While commitment in marriage is laudable, even a part of the institution’s very essence, there are significant differences between the commitment of the widowed Moabitess Ruth to her widowed Israelite mother-in-law and a modern bride to her groom.

Contemporary Significance

RESPONDING TO HUMAN TRAGEDIES. What the world attributes to large impersonal forces of nature and chance, the Scriptures attribute to the sovereignty of God. This is a fundamental teaching of the Bible, and the book of Ruth stresses it throughout its pages. How we respond to the circumstances that God may bring into our lives often determines further outcomes. Elimelech’s response to the famine was to move his family to Moab—a decision contrary to God’s revealed will for his people. The sons’ decision to marry Moabite women was also contrary to God’s revealed will. These decisions spelled disaster for the males of the family, not to mention the grievous situation that came upon their women.

The disastrous circumstances and situations that the prologue describes are outside the control of Naomi. While the disobedience of others during the period of the judges may have brought God’s judgment through the famine, Naomi had no way of controlling this. The decision to move to Moab was, undoubtedly, outside her control—Elimelech is the responsible party here. And the ensuing tragedies of the deaths of her husband and sons were all beyond her ability to intervene.

Accidents and tragedies strike Christians too. I am reminded of a former neighbor family, three born-again Christians, in which the husband and teenage son were suddenly killed in an auto accident when the car they were in simply spun out of control. The accident left the wife completely alone. The doctrine of God’s sovereignty is not especially comforting at that moment. Furthermore, the fact that others have gone through similar disasters is not usually much of a relief at the time. Yet these situations, which God in his administration of his kingdom may permit, are often the very circumstances through which God acts in compassion and ḥesed for his people. And it is through these conditions that the ḥesed of God’s people themselves is evidenced.

It is easy to live out the belief in God’s sovereignty when things are going well. When one good thing after another comes along, we can easily acknowledge and praise God’s sovereignty over our lives. But when disasters strike, when one bad thing after another piles up, the doctrine of God’s sovereignty is harder to accept and live out. The person who believes in the sovereignty of Yahweh and feels pounded by catastrophes that he or she believes God has allowed must come to terms with what God is doing in his or her life. Is God judging or chastening for some open or hidden sin? Perhaps. As the book of Job conclusively demonstrates, however, perhaps not. Sometimes disasters come, and the suffering that takes place is not the result of God’s punishment of sin in the life of the believer. Sometimes it comes in order that God may glorify himself through the believer’s life.

This is not the place to develop a theology of suffering, yet Naomi, like Job, faces great anguish, grief, and suffering, and not necessarily because of something that she has done wrong. There are always “friends” (like Job’s) and theologians who have their “pat” answers for disasters and suffering. While God allows emptiness to come to Naomi, he does so in order to bring her fullness once again in an even more significant way and brings great glory to Yahweh, the God of Israel, who keeps ḥesed to a thousand generations. But while Naomi is in that state of anguish depicted in chapter 1, she registers the real pain and anguish that a person who believes in God’s sovereignty sometimes feels in the midst of disaster. The tremendous pain and affliction these trials bring is real and sometimes impossible humanly to handle.

God’s sovereignty over life. I am not saying Naomi (or Job, for that matter) is right in her railing against God at the end of chapter 1. Her understanding and conclusion that God is against her and has brought these disasters on her because he is against her is wrong. Similarly, Job is wrong in his view that God is arbitrarily judging him, pounding him into the turf for no good reason. What is truly amazing is that although both Naomi and Job are wrong in their assessments of God’s actions, neither suffers because of their accusations of God’s determined punishment on them. Their sufferings are for reasons that go beyond them—they are part of the greater plan of the Almighty in his administration of a complex universe. The stories of Naomi and Job give us a glimpse at that plan and the place that our own suffering may play in it, allowing us to face that suffering with fuller knowledge of God than we might have otherwise.

In recognizing Yahweh’s sovereignty over her life, Naomi feels that this confirms that Yahweh is against her. But in his gracious ḥesed, Yahweh was not against her. Rather, he has provided food to his people (1:6), which serves to stimulate Naomi to return to Bethlehem. In attempting to deal with her anguish as best she can, Naomi saw logically that it is better to trek back to Bethlehem and possibly survive than to stay any longer in Moab and perish. God sometimes closes our options and leads us through “no brainer” guidance.

In addition, he has provided Ruth, who will not be shaken by Naomi’s logic to return to her people, but who instead manifests incredible ḥesed to Naomi and faith in Yahweh. But Naomi, because of her natural self-absorption because of her pain and affliction, cannot see it.

This is certainly true for us too. Often in the pain and affliction of life our perception is obscured. We depend on our logic, which is helpful to a point (fortunately God has given us this). But human logic often breaks down in the midst of pain. In fact, if Ruth had followed Naomi’s logic as Orpah did, then Naomi’s logic would have completely eliminated any chance of a reversal in her fortunes. Thankfully, Ruth does not “buy into” Naomi’s logic (in spite of Naomi’s three attempts to dissuade her from coming). Human wisdom does not accomplish the will of God.

There are times in the life of every individual when loneliness sets in. There are two kinds of loneliness: one that we feel when there is literally no one around, and one we feel when we are with people but unable to really communicate the longings or struggles of the heart. Thus, no matter how many friends one has or how happy a marriage or how connected to the children, there are times when we all feel lonely. It is not necessary that we have gone through the same exact experience of Naomi in order to feel the depths of her aloneness, hopelessness, and despair.

For the most part, we attempt to fill the void. We have work activities and family activities and all kinds of other activities to keep going and fill that void. We have dreams and goals and achievements that keep us focused. Yet, in the quiet place of the soul can be found that sense of loneliness, that sense of “I’m not sure I fit,” of “I don’t feel understood or appreciated.” When the things with which we have filled our lives are removed, the void caused by aloneness screams out. That void can only be soothed by one relationship—relationship with Jesus Christ.

Amazingly, our laments and complaints while going through these trials are registered. God hears them, even though we often may think not. And God has been subtly at work answering Naomi’s blessing on Ruth as well as her complaint to him. This gives us assurance that he will do the same.

In an age when familial responsibilities are rationalized away, passed off, or simply ignored, Ruth’s commitment is a powerful testimony. Such needs within families still exist in the modern world. Tragedy can and does strike, but it is still God’s plan that the family be the structure in which comfort, commitment, and resolution to pain and anguish be found.

Moreover, in the larger context of the church, such ḥesed as Ruth’s is desperately needed. If the Galatians 6:2 instruction to “carry each other’s burdens” has any meaning, certainly Ruth’s actions are an evidence of it. Where we can help ease the pain of individuals within the body of believers, we should do ḥesed.