Dr. Pell arranged for a shallop to take Balty, Huncks, and Thankful to Oyster Bay, where they would rendezvous with Captain Underhill.

Underhill, Pell told them, had recently married a Quaker woman. She would see that Thankful got settled among the Quakers of Vlissingen—Flushing, as the English called it. Stuyvesant had tried to ban the Quakers there from holding meetings. They sent a petition—now known as the Flushing Remonstrance—to Stuyvesant’s superiors at the Dutch West India Company. Amsterdam overruled Stuyvesant, much consternating him.

Pell was greatly amused at the rumor that Underhill himself had converted to Quakerism.

“The hero of Fort Mystick and Pound Ridge—a Quaker!” he chortled. “New England’ll do queer things to a man, and that’s no lie.”

He warned them it was far from certain Underhill would lend his support to Nicholls’s seizure of New Netherland. The old warrior was sixty-seven now. The “Cincinnatus of Long Island” had laid down his musket and taken up the plow (Tobacco). Age, farming, and Quakerism mellow a warrior.

On the other hand, Pell said, Underhill loathed the Dutch and “Old Petrus”—Stuyvesant—in particular. Underhill knew him well, having lived in New Netherland for years. Underhill had been sheriff of Flushing. But in 1653, he broke with Stuyvesant over his autocratic ways, denouncing him as a “tyrant.” That earned him a spell in Stuyvesant’s jail. A year later, at the end of the Anglo-Dutch War, Underhill moved away to the edge of New Netherland, to put distance between himself and his nemesis.

Like most New England eminentoes, Underhill was born in England, in Warwickshire. His grandfather Thomas was Keeper of the Wardrobe for Queen Elizabeth’s favorite, Robert Dudley, First Earl of Leicester. Dudley was imprisoned in the Tower of London over the plot to install Lady Jane Grey on the throne. He was eventually released, unlike his less fortunate brother Guildford, Lady Jane’s husband. A half century later, the Underhill family got itself mucked up in another plot, this one the Earl of Essex’s attempt to dethrone Queen Elizabeth. The Underhills fled to the Netherlands.

The future Captain Underhill was then four. He grew up among the Dutch, married a Dutch girl, had a Dutch son, then emigrated to New England aboard Arabella, flagship of John Winthrop, founder of the “city upon a hill,” the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Underhill became a soldier and Indian fighter in the Bay Colony militia, rising to rank of captain. The Bay Colony elders dispatched him to Salem to arrest Roger Williams for promulgating his heretical view that the English should pay Indians for land rather than seize it. So began his disenchantment with Puritan theocracy.

Two years later, he got himself banished from the Bay Colony for anticonformism, along with his friend Anne Hutchinson. He became a soldier for hire, privateer, sheriff, and general dissenter. Along the way, he forged a bond with Winthrop the Younger, Governor of the Connecticut Colony, providing him with intelligence on Dutch schemes to foment Indian trouble in English territories.

Following the massacre of Anne Hutchinson and her family on what was now Dr. Pell’s land, Underhill played a role in the ensuing Indian war. Receiving a report that a large number of Siwanoy and Wappinger were encamped at Pound Ridge, Underhill marched his men from Stamford through a bitter winter night. They surprised the Indians and encircled their palisaded village and put it to the torch. Those who tried to flee were shot down. The Indians resigned themselves to the fire, man, woman, and child dying in silence. Veterans of Pound Ridge, whose butcher bill of seven hundred was eerily identical to that at Fort Mystick, were haunted to the end of their lives by the memory of that terrible silence, the only sound the crackle of flames and hiss of melting snow.

Now, in the winter of his life, Underhill distrusted and deplored all authority, Dutch and Puritan. Planting himself in Oyster Bay on the Long Island put water between him and Stuyvesant, and between him and the Puritans. He was moated, finally at peace.

Dr. Pell said the best hope of getting Underhill to join the fight would be simultaneously to play on his loathing of the Dutch and Puritans: losing New Netherland would stick it to the Dutch, while Puritan New Englanders would shudder at the brazen action by the new English king they despised. What might he do to them? If Charles II would seize New Netherlands, what would he do to his own functioning colonists? Dr. Pell chortled. That would that put a chill into their already cold spines!

* * *

Balty stood on the Fairfield wharf, forlornly regarding the shallop. It resembled a bobbing coffin. The prospect of another sea voyage—and this across a body of water called the Devil’s Belt—made his innards wormy. Thankful, ever attentive, tried to jolly him. What could be more invigorating than a brisk sail on a moonlit night?

He was having none of it. Brisk their journey would certainly be, for the wind was increasing to a howl. The shallop’s halyards and stays slapped against the mast. The wind was northwesterly, which—apparently—would make for a good “reach” southwest across the Belt to Oyster Bay, a “mere” (as Thankful cheerily put it) thirty miles. God willing, she said, they should fetch their destination at first light, “with a pretty dawn at our backs.” Balty was having none of that, either. An invocation of “God willing” invariably prefigured disaster. Thankful told him to hush and bundled him into the boat.

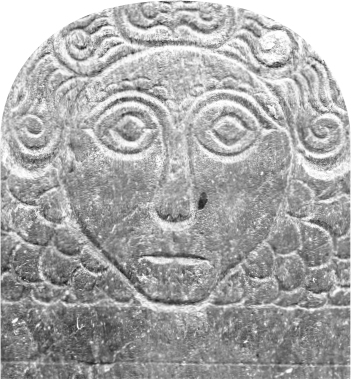

Dr. and Mrs. Pell were there to see them off. Pell gave Huncks a letter for Underhill sealed with his signet, whose emblem was a pelican. He hadn’t seen Underhill since Fort Mystick, over a quarter century ago. Bygones should be bygones. There were bigger matters at stake than holding an ancient grudge. That said, Pell warned, Underhill was a stubborn old bastard.

“You’ll have no trouble finding him,” he said as the shallop’s skipper cast off lines. “His is the largest estate on the Long Island. Named Kenilworth. Or Killingworth. Worth killing for! Ha!”

As the boat pulled away from the dock, sails snapping full with wind, the doctor shouted, “It’s a clever man who weds a rich widow!”

Mrs. Pell boxed her husband’s ear. Then, arm in arm, they waved as the boat sailed into the gusty night.

The skipper was an incessant talker who delighted in regaling his passengers with lurid accounts of terrible wrecks along the Belt. Another favorite theme was harrowing accounts of painted savages paddling long wooden war boats called canows carved from tree trunks.

“You’re not wanting to see one of them coming up on yer arse, let me tell you. Oh, no!”

Woozy, Balty nestled his head on Thankful’s lap and murmured, “Offer him money to stop talking.”

Huncks enjoyed the old salt’s palaver and stoked the conversation with his own memories of the diabolical Belt. The two prattled happily away, exchanging stories of skirmishes with Indians along the shore and of people being eaten by large fishes with triangular fins that cut the surface like axes. Balty groaned and nuzzled on Thankful’s lap. She giggled and cupped her hands over his ears to spare him the more gruesome snatches.

The wind increased. The shallop bucked, waves slapping against the sides and slurping over the gunwales. Thankful recited from memory the Gospel story of Jesus calming the storm on the Sea of Galilee as his disciples huddled, whimpering, in the lees.

Irritated at being compared to timorous Judean fishermen, Balty moaned, “Why don’t you ask Jesus to calm this bloody sea?”

Thankful shook her head. “I thought thee fearful. But now I see thou are brave.”

“Brave? How?”

“To blaspheme on such a sea as this. No timid soul would tempt our Lord so to sink his vessel.”

Balty groaned and closed his eyes, and burrowed deeper into Thankful’s lap. It was the loveliest pillow he’d ever had. He opened his eyes and looked up. She was looking down at him a certain way. She bent closer. Their lips came together. For a moment the wind ceased to roar in Balty’s ears and his stomach calmed. Indeed, the boat itself seemed to hover, still, above the menacing waves. Then came a tremendous bang and shudder as a cataract of seawater roared over the side, drenching them to the skin. They sputtered and coughed. Huncks and Thankful and the skipper roared. Without understanding why, Balty found himself laughing.

Huncks rummaged in a bag and produced a bottle of Barbadoes rum and passed it around.

The skipper pointed to a low, white spit of sand on the Long Island shore.

“Eaton’s Neck. Good harbor in a nor’easter. Belonged to Eaton, him who founded New Haven, with the minister, Davenport. Bought it from the local savages, Matinnecocks.” He took another long pull on the rum bottle. “He sold it to his son-in-law, Jones, under-governor of New Haven. Then Jones, he sold it to Cap’n Seeley. That is, Cap’n Seeley thinks he owns it.” He laughed. “The Matinnecocks sell the same land to different folks. Keeps the courts busy!”

They dropped anchor in Oyster Bay at first light. As Thankful had also predicted, the dawn at their backs was pretty.