If I had to take you down the road of substance abuse, from first use to addiction, it would be this in a nutshell: it starts off fun, gets less fun, then scary, then necessary. Necessary isn’t really scary or fun, it’s just . . . necessary. That’s the progression I see in the lives of addicts I serve and that I recall myself. Remember the old commercial that said, “Nobody wants to grow up to be a junkie”? That’s so true. We don’t start getting high because it sucks; it’s fun at first. We don’t consider the long term. If we did we would stop in our tracks, considering what it’s like to dream about getting to rehab if we’re lucky, or die young if we’re not.

We just want to have fun, kill the boredom, relax, laugh, stop feeling, be accepted, impress the girl, show them we’re more than they think, get back at them, shut our brain off, escape the shame, stop the pain—those kinds of things.

Nobody takes their first hit giving thought to what their last hit will look or feel like. If we did I think we would all be done after one time. I wish I could play a few tapes of people calling into rehab at the end of addiction asking and begging for help; or parents who cry openly with a complete stranger while talking about their kids; or people telling us about their best friends who have become strangers; or those who tell us how the person they fell in love with and their greatest joy in life was now the source of their deepest pain; or kids desperately trying to help their parents. The heartbreaking stories of addiction I’ve heard talk about the destruction of lives and communities, sometimes for generations.

Addiction doesn’t end well. Like ever. There isn’t a single person I know who came out of their addiction because things were going awesome. That’s not how it works. Losing a job, legal trouble, losing your family, seeing/doing/having awful things done to you; these are typically the kinds of things that make people think about addressing their addictions. It takes serious motivation and perseverance for people to go through what it takes to not only get sober but to stay sober those first couple of years. It takes guts to say you’re willing to try to stop and something much bigger than guts to stay stopped.

Because we all have an idea in our mind of what an “addict” looks like and because this book is about weed, I want to describe what a THC addict can look like. Many people can recognize alcoholism if you’re around someone who is an alcoholic long enough. Unfortunately, many of you can recognize other forms of addiction; gaining that knowledge is never fun. It’s wild, however, that many people don’t recognize what THC addiction looks like. Please keep in mind that the only way to say for certain if someone is an addict is to have a professional diagnose him or her with substance use disorder (SUD), but there are things to look for.

I’m typing this on a plane coming back from South Carolina. I gave a talk at a university and was asked by a student at the end of my presentation if you could tell someone was using drugs by their social tendencies. The question was well-intentioned but I chuckled a bit. If we could determine who was using based on what they liked to listen to, I believe anyone who drove around with me for a couple of days would probably think I got high! So be careful not to judge based on these things but instead use common sense. Parents, especially, should make it their job to ask lots of questions and know what to look for.

Cannabis use disorder is a real thing, and is included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the American Psychiatric Association’s universal authority for those in the mental health field. According to the federal agency that tracks this stuff, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 4.2 million Americans over the age of twelve met the criteria for cannabis use disorder in 2015. Symptoms include the following:

Disruptions in functioning due to cannabis use

The development of tolerance

Cravings for cannabis

The development of withdrawal symptoms, such as the inability to sleep, restlessness, nervousness, anger, or depression within a week of ceasing heavy use

Etc.

That’s some of what defines a technical addiction to cannabis. Defining addiction isn’t subjective. Like diagnosing any other disease, one either meets the diagnostic criteria or one does not. I get asked all the time, “Is weed actually addictive, is that a real thing?” The fact is that the only debate about this is the one put forth by The Lobby/Industry. It would be like asking if Wyoming really borders Colorado to the north. I don’t have to answer that question with an opinion, in the same way I don’t have to answer the addiction question with an opinion; THC/marijuana is addictive, and if a person meets the criteria they are clinically diagnosable as addicted to the substance. Now, it is less addictive than some other substances but that reality is changing as we study it more and as the potency increases. The bottom line is that addiction to THC is a very real thing.

What Does THC Addiction

Look Like?

So now that we have covered the technical stuff, let’s get into practical application. Traditionally, weed addiction has been pretty subtle. The way it manifests doesn’t happen overnight and isn’t typically a huge explosion. There are exceptions, of course, but for the most part addiction to this substance takes more time to manifest and doesn’t do so in a fiery mess.

Frequency of Use and Potency

If anyone is using more than a couple of times a month that’s a warning sign. The younger someone is, the more concerned I would be about the frequency of their use. Think of it like alcohol. If an adult was getting drunk more than a few times a month you might be concerned. Since nobody is using THC for the flavor or for any reason other than to get intoxicated, frequent use is something to watch for because it equates to frequent intoxication. Now if the person getting drunk is a kid, then a couple of times a month is a different story, it’s more pressing. The same things apply with weed use.

If someone is using THC multiple times a week, pay close attention and ask some questions. What would happen if you stopped for seven days, thirty, sixty? If the answer is “No big deal, I do it all the time” then I would worry less. If the thought of stopping for a few days freaks somebody out and they push back hard or get angry, that would concern me.

In addition to frequent consumption, the potency of what people are consuming is worth considering in today’s day and age. Someone using concentrates once a day is a pretty big deal; it might be equivalent to a person smoking regular 25 percent THC weed multiple times a day. Just think of it simply: too often/too strong should give us pause.

Reasons for Use

People will often talk about benefits of use when in reality many are telling us about symptoms of withdrawal rather than benefits of using. The benefit is that consumption keeps the withdrawal symptoms at rest. We’re going to talk about withdrawal in a second, don’t freak out yet! Being anxious and nervous when you stop consuming are withdrawal symptoms as well as trouble sleeping and feeling nauseated.

When someone tells me that they need THC to sleep, I know that’s real; they may very well be experiencing subtle symptoms of withdrawal. It sounds kind of backwards, right? Lots of stuff that isn’t good for your body will make you go to sleep.

The Challenges of Confronting a THC Addict

One of the most challenging things recently has been people who clearly meet the diagnostic criteria of cannabis use disorder telling us that they aren’t addicted because one can’t be addicted to weed. I actually saw a nineteen-year-old patient arguing with an addiction-specific physician whose career is working with substance use disorder. The patient was telling the doctor that she had it all wrong, weed wasn’t an issue because it isn’t addictive—and he was in rehab.

People seem to recognize that if they can’t stop using other substances, and if those other substances are having very negative effects on their lives, they might have an issue. It seems harder to have that talk with people today about weed, especially younger people who are so much more vulnerable, identity conscious, and easily manipulated. With that in mind, realize that talking to people who might be addicted to THC can be pretty challenging.

Keep in mind that if someone really is addicted to something, they aren’t excited about it. They might be resolute on the outside about it being no big deal, or a choice, or a necessary medicine, or a way to find their identity, but if my experience is any indication, that person wants out even if he or she can’t say it or imagine being out. My friend Keith, the interventionist I mentioned earlier, sums it up best. People are always telling him how tough their loved one is going to be and that they will never agree to treatment. Keith says this, “I know a secret, because I’ve been there. I know that deep down inside they don’t want to live like this. They just can’t imagine anything else but they hope for it even if they don’t know what it (sobriety) looks like.”

THC Withdrawal

A full discussion of withdrawal is so crucial and important when considering the direction we are heading that I almost gave it a chapter of its own. It is such a big deal that I talk about this in the first few minutes of almost every talk I give.

For the first time ever, cannabis withdrawal was included in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the American Psychiatric Association’s universal authority for those in the mental health field. The fifth revised version of this manual came out in 2013 and includes signs and symptoms, as well as diagnosing criteria for cannabis withdraw. This is the manual for this stuff. It’s not a political document or opinion, it’s a medical diagnostic criteria developed by experts in the field.

Withdrawal from weed wasn’t included in the previous four versions because it was so rare, if it existed at all. This is such a key part to understanding THC today compared to the weed of years gone by. At 4 percent THC, people weren’t detoxing from weed, they just stopped. When Willie Nelson started smoking weed he could have put it down without much consequence. In all likelihood, it would be very different for him to stop today. Because it’s so much stronger today, it affects the human body much more than before. Coming down off of weed isn’t going to kill you like alcohol or benzos can, and isn’t going to have you on the floor in the same way that opiates do, but it can really be miserable. It is also very unpredictable. Because of the way THC metabolizes in our bodies it tends to hang around much longer and sometimes come back around when someone thought they were all detoxed and clean. We can do a pretty good job predicting how a person will detox from almost all substances, but THC is an exception. We are getting better at it but THC is really unpredictable and there are no medications to aid in the detox process from weed.

Indiana Jones is lame now. Star Wars sucked then got cool again. The Cubs finally won the World Series. Johnny Cash is gone. Cars are starting to drive themselves. People are having to detox from weed. What’s the world coming to?

Addiction can look very different on different people so consider the things above and ask a professional if you have questions. If you go to a doctor, you should probably look for one who is certified by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) or American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM). If a therapist, find someone who works regularly with addiction. There are plenty of people who can help.

Why We Get High—

Continued

I gave a partial list earlier of why people feel the need to get stoned, or at least a partial list of things that influenced my use. However, this is such a big question that people have dedicated their lives to researching it, and we could fill several books with what we know and still not get it all down. The reasons are as diverse as the individuals who use and many of them apply to a variety of substances. It’s more about the person than the substance. I know guys who use porn for many of the same reasons I used drugs and drank. Some people use food or exercise the same way. It’s about the person not the substance. The unhealthy and often dangerous behaviors sometimes make sense when you understand a person’s history.

Since this is a book about weed, I’m going to stick to that when answering the why we use question. Given all of the reasons mentioned earlier there are some things specific to weed and specific to weed in Colorado that deserve special mention.

People use because they are told and believe that weed/THC is harmless. There is such an effort to convince us that it’s a lesser evil or not an evil at all that people are starting to believe it. We are told that it’s safer than alcohol and, unlike other drugs, that it has never killed anyone (see Chapter 7). It’s interesting to consider who is giving us that message. It’s not the American Medical Association (AMA), not the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) or the American Psychiatric Association (APA). It’s a message brought to us by the guys lobbying for the sale of the drug. Economics, not science, has driven this message.

People use because it’s easy to get. We know that the easier the access, the more people will access it. Weed is easier to get than meth, so more people use weed. Alcohol is easier to get than weed, so more people use alcohol than weed. This is a simple observation that holds true across any example. If there are eighty-plus more dispensaries in Denver than there are McDonald’s and Starbucks combined, then does that mean it’s easier to get a joint and a THC cookie than a latte and a burger?

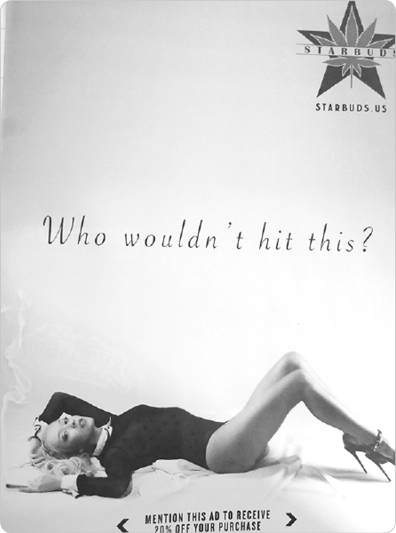

People use because they are told to and are pressured to. The less people are exposed to a thing and the less they are encouraged to use that thing the less they will use it. It’s that simple. Ask yourself if the advertisements below are “exposing and encouraging”?

The Culture

One of the smartest and most compassionate people I know in the treatment field is Dr. LaTisha Bader. Dr. Bader and I did a talk together a year ago for a bunch of sports psychologists in Big Sky, Montana, about THC. As Dr. Bader and I were preparing the presentation, she shared a chart with me highlighting several areas of culture that are influenced by addiction as well as recovery. We used it in our talk to show how recovery and addiction can look in regard to THC use. Those areas are highlighted in the list below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All of these areas can be dramatically influenced by a person’s drug use. What I’m increasingly seeing more of is the huge subculture around marijuana use. When you have pop-up ads for weed shops on the Internet every time you read a story about weed it should tell you something about the proliferation and normalization of a culture integrated around marijuana use. What was once a counterculture is now a subculture, and if left unchecked will just be our culture. Weed has its own magazines (way more than just High Times), radio shows, more websites than I could count, and now associations and trade unions. The Denver Post, Denver’s major daily newspaper, has a specialty publication called The Cannabist, which it says addresses, “cannabis’ ever-expanding role in our weekly lives via news coverage, pot-rooted recipes, arts features, strain and gear reviews, lifestyle profiles, business articles and more, more, more.” The Post, which had been struggling as were most daily newspapers, now gets big ad revenue from the numerous Cannabist advertisers. With the huge THC-based industry now driving its own culture, it is getting easier to become immersed in the overall drug culture. For many users it’s become a second family, a group of people who not only accepts them but encourages them to go forward in their use and often discourages them from getting help. Even if their peers were to encourage them to stop using, the reality is that in addition to losing the substance they have come to rely on, people who quit getting high also stand to lose identity and community. While this exists with alcohol, marijuana is unique in that it has become so widely accepted, and many people are using it to establish their personal and social worlds and worldview. I’ve never seen a person wearing a hat about meth or heroin socks but see both featuring weed daily.

How to Help

Nearly every day, I’m asked what someone can do to help a loved one who is addicted to THC. The answers are as diverse as the people who ask. While every situation is different, one thing that can be said for everyone wishing to help is to lead with love and compassion. It isn’t about shaming someone into wanting to stop or scaring them into it. Help must come from a place of love. When it comes from the heart, your caring will be evident and, as a result, it will be much easier for the person to hear. There are also times when one has to say “Enough is enough,” then set boundaries and stick to them, no matter how hard that is.

A crisis can help a person be more willing to get help but avoid talking to a loved one in crisis, if it can be avoided. For example, if your loved one comes home high and you have already been talking about his or her substance abuse, you will likely be pretty angry. If you’re not careful, trying to help when you’re upset stands to be more about you than them. We tend to react when we’re upset and those emotions can make the conversation that needs to happen much harder. As opposed to getting into it when you’re fired up, consider giving it a day and having that talk when things are going well. Sitting down to a meal together the next day might help your message be heard and help you come into the conversation with a level head, more capable of delivering that message out of love and compassion than anger. This isn’t to say that emotion is a bad thing when talking to someone about their use. It wouldn’t be real to try to do it free of emotion. Just consider how you can best do it out of a place of love over anger, those messages are often heard better by the addict.

The most effective thing you can do is to enlist the help of a professional. There are some amazing people out there. The right interventionist and treatment center can be a true lifesaver. There are lots of people out there so choose carefully. Don’t be fooled by slick sales pitches and flashy websites, ask some hard questions. You can also talk to your doctor and ask for referrals to physicians who specialize in addiction.

This can be a really tough thing to do so don’t do it alone. Get other people who know what they’re doing and enlist their help. You can also ask someone you know who has been sober for a while for help, we love the opportunity to help out in times like these.

Of course, if there are any circumstances that make you think a person’s use is immediately life threatening, that whole waiting for the right moment thing goes out the window. Get help right away and do whatever it takes to help.

The hardest news very well may be that even if you do everything perfectly there are no guarantees you will be heard or that treatment will be “successful.” I’m asked all the time what will do it, what will “fix” a loved one from their addiction. The reality is that there isn’t a formula that works every time. There are so many factors and ways to help that it might be beneficial to look at it like stacking the right blankets on somebody who is freezing. If you stack enough and if they are the right kind, the odds improve with every blanket. We want to give the addict every opportunity to “warm up” that we can. The thing that is so hard to communicate and to hear is that there are no guarantees, and anyone who is telling you otherwise is just giving you a sales pitch—there is no silver bullet. So many things can help, and the right combination of those things (meds, support groups, therapy, treatment, behavioral interventions, monitoring, exercise, etc.) can give the addict a very good chance; but not a guarantee.

I spoke to a friend this week whose story helps to make this point. She has been through the ringer with THC addiction in her family. She has a perspective that I don’t often see; she has set boundaries to protect her family, loves her son very much, and continues to show that love and offers help to him. She speaks openly about her experiences and offers help to others in similar situations. She is an inspiration and a great example of how doing all we can sometimes doesn’t produce the results we are hoping and praying for. I’m going to share a bit of their story, beginning with how her son was first exposed and how things progressed. But this is mostly a story about how to help. The names have, of course, been changed, and changed awesomely might I add. I’ve had my name changed in a few books and they always come up with something way lame, not this time!

Shera has two sons and was career military. She went on to work for a charity helping veterans when they left the service when she retired. She is charming, well spoken, smart, and the kind of person people just like being around. She is also someone who knows what it’s like to be sick. In fact, she was diagnosed with two of the chronic and life-threatening conditions that many claim can be cured by weed. Being someone who relies on doctors rather than budtenders, she is treating these illnesses traditionally and not getting high.

Shera speaks often of her son, Bosco, both publicly and privately. I have never seen her do so without class and respect for him as a person, which is refreshing in this conversation. Bosco has been in and out of recovery and is also very open about his struggle.

He started getting high in junior high school and hit it pretty hard. The weed was easy to get, mostly from the parents of friends or people who had med cards. Early on in high school, Bosco discovered “dabbing” and things got pretty bad for him pretty quickly. As we discussed in the chapter on concentrates, this stuff is nasty and we don’t know what it’s doing to people’s brains, and especially in the brains of teens. It is bad news and this form of marijuana doesn’t have a place in the world.

Because of a variety of factors, including tolerance to THC, cultural acceptance, and availability, Bosco was using concentrated THC regularly, sometimes even more than twelve times a day. His parents sought help through the military healthcare system. After a few visits with a doctor doing talk therapy at the VA, Bosco was told that he needed inpatient rehab to address his addiction to THC. He responded like most young people do, telling the mental health professional that a person can’t get addicted to weed. But he capitulated and went to rehab anyway.

When Bosco left rehab he was fired up and did well for a bit. He even talked publicly about how the culture made it so easy for him to get high. He spoke about getting his med card after telling a doctor he had a knee injury from football (he never played), and how the doc bent his leg a few times and gave him the approval. He described how afterward, as a card-carrying “patient,” he was in high demand. Being signed up with a “caregiver” would allow that person to grow lots of additional plants to supposedly support his “treatment.”

According to Colorado law, a patient can only change caregivers once a month, but Bosco did it all the time. He was a patient at most of the medical dispensaries in his town. This is illegal, of course, but the letters the state sends telling you to knock it off aren’t worth the paper they are written on. He was very frank about how the culture aided his addiction, but The Industry was what allowed him, an eighteen-year-old kid, to get high all day, every day, at almost no cost. He became an expert at how to work the system and to clip coupons—literally clip coupons.

When Bosco came back from treatment he was ready to stay sober. He got a job delivering pizzas and was working to get his life back on track. As someone with a few years of sobriety, I can tell you that living in this kind of environment can be intense. For Bosco, the pressure was way intense. He would often be offered weed as a tip for dropping off a pizza; it’s practically a currency here! And he was surrounded by stores, advertisements, the culture of gratification and abuse, and the sheer smell of it. The challenges proved too much to resist in his early recovery. Bosco ended up relapsing and is currently living in a “gray market” grow house. It basically functions as a co-op where a group of people are growing their legally allowed six plants each, but in the same place. There are many more people on the books than are actually growing weed. This kind of arrangement makes large-scale growing kind of legal-ish should they get raided.

How many doctors that you know hold “patient drives” to drum up business?

Since demand is so high for “patients” the perks one gets with a red card go way past not having to pay taxes. Readily available is free weed, free pipes, free weed, clothing, free weed, buy one get one deals, free weed, contests, free weed, food, and barbecues—and did I mention free weed?

Bosco has had a rough go of it, and it’s one that I intimately understand myself. Shera also has had, and continues to have challenges along the way, too. Since my experience is only that of the addict, I asked Shera what she thought other parents might benefit from hearing.

Everything she said came back to her love for Bosco, as well as for her husband and other son. She is clearly motivated by family. She shared some of the family traditions they kept, what it was like in their home, and how much she cared for her boys.

Shera told me that if she could do it again, she would have paid closer attention to the families of Bosco’s friends. There were instances when those parents were disconnected from their children and times when some of them actually shared weed with the kids. She wishes she had known those families better at the beginning before allowing Bosco to spend time there. As a parent of three young children, I know how awkward it can be when you tell a parent that your child can’t go over until we all get some time together. It’s hard for them to think they’re not trusted, but we don’t automatically assume all parents are trustworthy. Until we know somebody, we don’t know them. In addition to asking about guns in the house and allergens (we have a few severe ones), we now ask about THC, especially edibles. Talking to Shera reinforced the importance of having these conversations.

She also said that she wished she had encouraged more extracurricular activities. Bosco was in ROTC for a time but other than that wasn’t involved in anything else. She now thinks that sports, clubs, or other healthy endeavors could have been a big help. But her bottom line was the importance of knowing friends and their families.

Shera and her husband had to ask Bosco to leave the house a while back. It was totally appropriate, agreed upon in advance, and even spelled out in a contract, but that didn’t make it easy. She continues to encourage Bosco and try to help him but they have also set up boundaries to make sure that their lives stay as manageable as possible in the midst of his unmanageable addiction. In a world that could use more love and more loving families Shera and her family are examples to me of how to do it well. I am optimistic about Bosco’s chances for recovery because he doesn’t want to get stoned. Although he can’t stop right now, it is his desire to quit using that gives me hope. His family isn’t giving up hope either, and they also aren’t accepting the nonsense going on out there in the free marketplace. Shera is vocal about how The Industry influenced Bosco and his life, and she is making her voice heard in the hope that other families can avoid the same things. Keep yelling, my friend, people will listen eventually. I hope it’s sooner than later.

Recovery

Getting sober is kind of the opposite of addiction; it starts out tough, gets really intense and then is one of the most rewarding things in life. It’s not easy to get sober. As anything that is worthwhile, it takes effort, grit, and determination. They say that the only thing you need to change in recovery is everything. Changing everything is rough! It’s also totally necessary. We all know plenty of people who don’t use anymore and aren’t anyone we want to be around; it has to be more than not using. Getting sober is much more than just quitting something, it’s about starting something. Sobriety involves starting to deal honestly with the world, starting to look hard at what our motivations are, starting to ask hard questions, considering the answers, and developing a willingness to start changing everything.

While the early days of sobriety are difficult, being sober is amazing. We gain clarity that would have been impossible and unimaginable when we were high. Connection with others and with a higher power has been one of the most rewarding parts for me. Not only is it easier to be present and live in the moment, I’ve found an acceptance of circumstances that I just didn’t have before. We are told that to stay sober we need to learn to accept life on life’s terms. While that doesn’t mean taking things lying down, it does mean that we come to realize that it’s not all about us, and that we need to allow others into our lives.

At the risk of sounding a bit cheesy, recovery isn’t a destination, it really is a journey. For those who love us and want to see us sober, what they are usually hoping for is that we stop getting high, not so much that we start doing all of those other things, it’s hard for them to see past the immediate. Getting sober isn’t really about not getting high but it starts there. If we were to stop at just not getting high anymore we would be a pretty rough crowd. So much has to be removed from our lives and changed, it needs to be replaced with something. Hopefully, that’s something healthier.

What It Looks Like

My first two years of recovery were really tough. I was only seventeen but had dug myself a pretty deep hole. I had all kinds of identity issues once I stopped using and, basically, I was a hot mess. I didn’t know how to act around people or how to go to sleep. When I did sleep, I dreamed about getting high and drunk just about every night, some of them so realistic that I woke up thinking I had relapsed. Having to feel for the first time in several years was probably the biggest shock. Being intoxicated mutes emotions in the same way it amplifies Yanni’s new age music (he is pretty hard to dig sober isn’t he?). I had grown accustomed to not feeling that which wasn’t physical, so when I started feeling my emotions again, it seriously freaked me out and I stuffed them deep down inside. The intensity of feeling again can be overwhelming. Keep that in mind if you are just getting sober or someone you love is new in recovery.

There were a few things that saved my tail in those first two years when things felt so rough. The first was fear. I was terrified of going back once I stopped. I lost three very close friends to addiction/

intoxication in that time and another was sent to prison for a term of twenty-five years to life. The stakes were high and I was reminded of them often. Before I got sober, I can honestly say that I had no real interest in being alive other than the basic biology of it. I didn’t want to die but I didn’t really care to be alive. When I got sober there were days—which increased in frequency the longer I stayed sober—where I really did want to be alive. A buddy describes getting sober as walking out of a really crappy matinee movie into a bright sunny afternoon, you feel so hollow when you walk outside, into reality. Until I was able to stop squinting and actually see the sun, lots of fear kept me from going back out. Thankfully, I will never know if this is true or not, but at the pace I was going and seeing what happened to most of my peer group, I doubt I would have made it another year; two would have been a very outside chance. For the first time in years, I knew that I not only didn’t want to die, I was getting interested in living again.

Another saving grace was the twelve-step program that I attended. I had something to put my energy into: I went to a ton of meetings! After doing court-ordered meetings—lots of them—and attending a bunch as a kid with a family member, I knew my way into “the rooms” but hadn’t ever gone there to work. My first two years I probably averaged eight meetings a week. Being around those people gave me the accountability that I needed, and it even gave me a little hope from time to time. I also had a few buddies who helped: Mike, Jay, Heath, and Doug saved my life more than once, and I’m forever grateful to them.

I also set a couple of goals early on that were a big help. I decided that I was going to finish high school and I made plans with three sober guys my age to travel the country as soon as I finished. Only two of us had our diplomas, and at age nineteen I was the last. Having the trip to look forward to and planning it with other guys in recovery was motivation in itself. When I finished school, we took off and spent the next three months driving. I got to see much of the country while living out of a car/tent and fell in love with Canada and Alaska. I actually celebrated my two years sober on that trip.

After that milestone it got much better, and I started to find some identity and peace again. I won’t go into all of it—this isn’t the place for that—but just like there were a few things that kept me sober at the very beginning, there were a few things that helped me make it those next crucial few years. I reconnected spiritually and went to work trying to understand what that looked like in my life. I had some dear friends who didn’t use and who played a big role in helping me create that new identity. If not for late nights playing basketball and building fires I don’t think I would have enjoyed those years nearly as much. Ben, Sammy, and Jon showed me what it was all about; I learned how to laugh again with them.

I also got super lucky and fell in love with the most amazing person I’ve met to this day. Christy gave me the final push I needed to want to live more than to be afraid of dying. With her, my life started to take on color. After gritting my teeth through the beginning, sober years two to five were actually beautiful. I felt like a kid (albeit one with a rough past who knew how to steal cars) learning about the world for the first time. It was a time of self-discovery and then of emotional awareness that I hadn’t experienced since childhood. All of this was topped off by falling in love and marrying someone who I can’t even imagine not having as my partner. My wife is the most inspiring person I have ever met and she motivated me to keep on working and growing.

The literature calls over five years “late-stage recovery.” It’s when we’re supposed to have it all together—ha! While you do have the tools to stay sober and keep growing as much as you’re willing to work for, life doesn’t stop happening and that means things can get really hard at points. I had a couple of those points in 2006, 2009, and 2012. These events were notably painful. Fortunately, I had the tools I needed to stay sober, and I had enough people who understood what I was going through in my life so I could process those things and try to integrate them into my life over time. Life won’t stop dealing us pain when we get sober; that is just part of the tradeoff we have to make for being alive. But the pain can be dealt with and processed so that we don’t destroy our lives or those of the people around us. Heck, if you can manage it like a few guys I know, that kind of stuff can actually make you a better person.

There is no certificate of graduation from addiction. There won’t come a day when I finally say, “Well, beat that one good, what’s next?” I will always have to work on stuff to stay sober, but the big difference today is that it isn’t something that I dread. I like living this way, and I want to continue learning and growing as long as I’m able. I’m glad that I will have the recovery community around me for whatever life hands me next.

With that said, my addiction and my recovery are less of my identity than they were in the beginning, and for me that feels right. I will always be an addict/alcoholic, but I am much more than that today. After twenty years of sobriety, those parts of my identity make up more of me than does the addiction. Before the identity of “addict,” I see myself as a husband, father, community member, productive member of society, climber, fisherman—that kind of stuff. It’s not that the addiction stops being there, it’s just under layers of other things today. So for me, that’s what it looks like. Seeing the change that takes place at the beginning is a big part of why I do what I do professionally. People walk in the doors hopeless and lost. We can help them find what they need to get sober and restore hope. Watching that transformation is unparalleled.

How to Start

Earlier I spoke to the person who has a loved one they are concerned about. This part is for those of you who think or know that you personally might have a problem.

First things first, you have to ask yourself how bad is it? If your life is in danger, hit the panic button. Go to the ER, go to a physician, get into the care of medical professionals right away. Treating long-term addiction is a specialty, so this will likely be just a first step. But you can’t get to step two if you’re not alive. If it’s life threatening don’t screw around, get somebody who knows what they are doing to help you.

If it’s not life threatening, let me encourage you to start out by hitting a meeting. There are so many meetings today that you’re sure to find something that works. Try a couple until you connect with someone. The advantage to this is that it’s free. You can go and start to look into all of this and it won’t cost you the price of treatment. This isn’t to say that treatment won’t be necessary but let’s cover that next.

Everyone is different and every meeting is different. Just like there is Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous there is now Marijuana Anonymous. Check out a few meetings before you make your mind up. I hear people all the time say that they can’t do twelve-step because of all of that God stuff. It’s not like that, seriously, and if you go to a group where it is not what you want then just go to another! There are actually a few twelve-step groups that totally omit a higher power component.

While it might scare you to think about walking into a meeting, consider some of the crap you have done to get high or while high. Compared to all of that, this is nothing! If you still feel too self-conscious, sit in the back and just listen. While some people will likely introduce themselves to you at some point, nobody will make you talk to the group if you don’t want to do it.

Treatment is a very necessary and lifesaving thing for many people. Let’s say you’ve abused your body or you have some mental health concerns that need professional help and maybe even medication. Treatment is a good thing, but make sure to pick a facility that is reputable; we can cover that later. Addressing those issues separately from the addiction can delay recovery on many fronts. Addiction is another chronic disease and it needs to be treated as such. It needs to be dealt with alongside other illness, be they mental or physical. The lack of respect for mental health disorders that people sometimes encounter is just a combination of ignorance and prejudice. My friend Patrick Kennedy, the former U.S. Congressman, is involved in the THC conversation because of his advocacy for mental health. He likes to say, “The brain is a part of the body,” and it’s about time this country starts to recognize that. It will make a big difference in our collective quality of life when we give as much attention to mental health as we do to physical well-being.

For some, getting medications right at the beginning is crucial if we’re going to maintain sobriety and mental health. Doing that during inpatient care gives the medical professionals the ability to see you around the clock and to make adjustments to things in real time rather than once a month when you have an appointment. It also allows them to monitor just what is going on physically with you in order to help in more than just one way at a time. Sometimes, what helps in detox might not help later on and vice versa, so being in a place where you can be treated around the clock can take months or years off of the time it takes to get your body (brain included) back on track in early recovery.

Treatment is also good because it’s a bit of a reprieve from the world. When your immediate needs are cared for (food, shelter, physical, etc.) it’s much easier to focus on doing that critical work that should be performed early on. I can only assume that my first two years of “tough” might have been reduced to a month or two if I had been under professional inpatient care and was just working on the issues at hand and not all of the other distractions that can throw you off track.

The stakes are high when it comes to dealing with addiction so don’t treat it lightly. While I always encourage the meetings first (they’re free!) most people with substance use disorder do need some form of treatment, and everybody could benefit from working with a team of dedicated professionals for a time.

If the idea is still scary but you think it might be right, make a few calls and ask tons of questions. A good program will be willing to answer anything you throw at them and help determine what you need. You can also ask to tour a facility, and seeing a place firsthand is a great idea.

Getting care from other professionals not in an inpatient setting is also a strongly advisable option. If the idea of treatment still freaks you out, that’s cool, just go see someone in their office. Be honest (you’re paying them so you might as well get your money’s worth) and see what they think the appropriate level of care is for you. If they ultimately recommend treatment you will have an ally to work with in finding the appropriate program. Make sure to find people who understand addiction and seriously, be honest with them. Nothing you’re going to say will freak them out and they aren’t there to judge you at all, just to help. Give it to them straight so they can help. Relationships with therapists/docs are professional relationships, this is what they do. It’s not a friendship so use their knowledge to get well, don’t worry about putting the best foot forward because that will probably slow it down in the end.

The “Other” Culture

I had to ask a couple of buddies about this one, “What is the culture of recovery?” It’s a big question and I don’t want to pretend to have the market cornered on this, even a little bit. I think it means lots of different things to people. There are, however, some common experiences and pieces of “culture” that lots of people seem to identify with being in recovery.

First of all, we’re the best designated drivers ever! If you’re lucky enough to have a friend in recovery you’re probably loving life when they agree to go out on the weekend. I’m a bit older now and so are my buddies but for a couple of years I got those calls pretty regularly. They went something like this:

Friend: Hey man, how’s stuff?

Me: You know, great.

Friend: Small talk (typically Broncos, climbing or fishing related depending on the time of year).

Me: Small talk right back (typically really witty and funny).

Friend: Sooooo, what are you up to on Friday night? Wanna hang out?

Me: Probably not but go ahead and ask.

Friend: Well, a bunch of us are going to go out to dinner and check out this show then maybe hang out downtown for a bit.

Me: Fine, I’ll go but I eat for free and I’m not doing karaoke again with you losers.

In addition to being on-call designated drivers there are a few more things about the culture of recovery worth noting. We can be painfully self-aware at times, and some of us never grow out of it. Imagine being in a room where everyone says exactly what they are feeling in real time and it typically revolves around themselves. That can be a lot like being in a room with folks in recovery. It’s not just about wearing our hearts on our sleeves; sometimes we straight up lob them around like grenades. The good news is that if we keep doing the work, this does ease up.

I also like to think that we are a little more willing to consider our own part in things and try not to blame people. We get so amazing at blaming others in addiction and especially early recovery. When we’re living in addiction our own contributions to a problem elude us and we tend to see everyone else’s shortcomings very well. For example, if you want to see the most entitled group of people on earth, let an addict be sober for like eight minutes and watch that show! Before they get “sober” they want all of the patience and understanding on earth, asking for one more chance, just one! Nothing was our fault and we can’t believe that you can’t believe us when we tell you:

It wasn’t mine.

I was holding it for a friend.

Someone must have put it into my drink.

I told them to either put it out or crack a window, it must be secondhand.

I swear to you, I didn’t.

I swear to you, I never will again.

They are lying.

I love you and would never do that.

Don’t you trust me?

Now flip the script to the addict who just got sober; we tend to demand absolute perfection from everyone around us:

You’re twenty-three seconds late! Clearly, you don’t respect my time.

Oh, you don’t know where the meeting is! Well I wonder what they’re paying you for “preacher”?

What do you mean you don’t believe me? You have no idea what I’m going through and what it took to get here.

But then something starts to happen. It’s hard to say when because it can be way different for everyone; for me it was about two years into things but I’ve seen guys get it after a week or two. I think they were able to be more honest and transparent than I was back then.

We start to realize: maybe the world doesn’t spin around us, that we might not be the center of everything. With that realization comes a freedom that is the beginning of the journey. If we stay on the path we start to get honest where we used to be less than honest, especially about who we are. If we are willing to be honest about what hurts we can start to heal and when we get to healing, the world hurts less and it becomes less about not getting high and more about living again. The second chance at life makes it tough not to do much of what we do out of gratitude and maybe even grace for others. We realize that everybody is hurting and dealing with it in their own ways. My buddy Bobby likes to say that, “We’re playing on house money,” because we have no business being here after what we have done but we are. Playing on house money is pretty liberating.

Like I said, recovery looks very different to different people. For me, the greatest gift has been my ability to go through life with some measure of compassion, grace, and honesty. Doesn’t mean I don’t hurt, or fear or doubt, or screw up, I do. I just spend more time today on the former than the latter.