CHAPTER FOUR

A Life Honorable and Amusing

THE CUSTIS FORTUNE SAVED Washington from financial ruin, at least temporarily. At the time of his marriage he was sinking deeply into debt. A brief note in his diary of 1760 reveals that he was so strapped for cash that he had been putting off one creditor for two years. The gentleman, running out of patience, came to Mount Vernon to ask for his money, and Washington was unable to pay him. This circumstance was so painful that when Washington recorded it in his diary, he soothed himself with the euphemism, “was unprovided for a demand of £90.”1

Washington was “unprovided” at the moment because he was awaiting the sale in England of his 1759 tobacco crop, but those sales proved unfavorable. His London agent sold the tobacco for less than £12 per hogshead (a barrel holding about 850 pounds); he suspected incompetence on his agent’s part as he had heard of other sale prices between £14 and £16. At the same time he was stunned to see a 25 percent increase in the prices he was paying for imports. “I cannot forbear ushering in a complaint of the exorbitant prices of my goods this year.… Let it suffice to say that woolens, linens, nails, &c are mean in quality but not in price.”2

Though Washington shipped more than 93,000 pounds of tobacco to England in the fall of 1760, the rendering of accounts he received the following summer was sobering: he was almost £1,900 in debt to his merchant. Like many other Virginia tobacco planters in precisely the same fix, Washington believed that the solution to falling prices and sinking profits would be found not in cutting back his expenditures but in expanding his planting operations. To accomplish this he had to buy more slaves and put more acres into production. He took a cash advance of £259 from his London merchants to carry out the purchase of slaves. The Custis estate had a credit of more than £2,000, which enabled Washington to obtain his loan; otherwise his note might have been refused.3

After three years of bad tobacco crops in a row, Washington had reduced his debt to his London merchants by only a hundred pounds. In a letter of September 27, 1763, he complained to his agents of his “manifest disappointments and losses” in the tobacco market, that his last shipment had been lacking a trunk containing £25 of linens and other items for Patsy (“disappointed she greatly is”), and that the hoes sent him “are so small and sorry that [the overseer] cannot possibly use them for they are scarcely wider or bigger in any respect than a man’s hand.” The money he acquired from his marriage to Martha was gone in four years, “swallowed up,” Washington wrote, by the expense of buying slaves, land, and provisions and by the cost of putting up new buildings at Mount Vernon. He was in debt for the sum of £1,800 in 1764.4

As a young man Washington had tasted the luxuries of Virginia plantation life at the mansion of the Fairfaxes, who possessed enormous wealth thanks to their control, handed to them by the crown, of vast territories in Virginia. Washington had also observed the agonies of those who wished to enjoy this lifestyle without the steady means to support it. When, at the age of nineteen, he accompanied his brother Lawrence to Barbados, he got to know the lifestyle of the large-scale sugar planters there. They did not live nearly so lavishly as he had expected, and the reason was their debt. He exclaimed in his diary how astounding it was to him “that such people shou’d be in debt! and not be able to indulge themselves in all the Luxurys as well as necessarys of Life.” Washington did not absorb this lesson well enough.5

The tobacco culture Washington inherited suffered from a cycle of economic boom and bust. Between 1744 and 1759 the price of high-quality tobacco fluctuated between £42 and £11 per hogshead.6 The planters adjusted for this as best they could, but when Washington entered the market in the 1750s the situation had changed, though Virginians did not yet know it. Before 1750, planters could comfortably take on debt in lean years, knowing that eventually a run of profitable years would enable them to reduce or eliminate their load; but after 1750 deep and prolonged depressions in the tobacco market made their debts permanent. At this same time the Virginia and Maryland planters developed a taste for consumer goods and did not care to delay their gratification in acquiring them. In the late 1750s Virginia was hit with a drought that ruined crops and brought a rise in interest rates. Despite an alarming number of bankruptcies in England and America, the planters viewed the problem as a temporary one.

The French and Indian War, which lasted from 1756 to 1763, was in effect a global conflict, during which the British and European economies suffered severe dislocation from the costs of prosecuting the war and the disruption of markets. The colonists expected a rapid recovery when the Treaty of Paris ended hostilities, but the opposite occurred. One Maryland newspaper reported in 1764 that “the bankruptcies in Europe have made such a scarcity of money, and had such an effect on credit, that all our American commodities fall greatly.” Prices rose for a year and then sagged for the rest of the decade as an economic depression settled in.7

Virginia planters built up debts they could not repay because they expected, by rights, to live well. They created a consumer society where wealth was made visible in grand houses grandly furnished in a manner the previous generation would have gasped at. In a pattern that future generations would follow, luxuries were redefined as necessities. The pride of the planters demanded that no expense be spared to proclaim their status. British magazines fostered a taste for stylish goods, and Virginia planters followed fads with greater speed and avidity than their richer counterparts in England.8

In the 1760s a Virginian noted with amazement that debts of £10,000 were thought nothing of, whereas twenty years earlier a planter would have been alarmed if he owed a tenth of that. As an example of colonial extravagance he pointed to the great planters’ new fondness for costly imported carpets. “In 1740,” he said, “I don’t remember to have seen such a thing as a [Turkish] carpet except a small thing in a bed chamber, Now nothing are so common.” Houses glittered with “every Appearance of Opulence.” He noted grimly that cash was not paying for all this conspicuous consumption, but rather “all this is in great Measure owing to the Credit which the Planters have had from England,” and that the planters were so busy spending that they did not know where the money was coming from. The colony’s governor reported to London in 1762 that Virginia’s debt was rising daily because of the taste for expensive imports, a disagreeable truth “that they shut their Eyes against.… I fear they are not prudent enough to quit any one Article of Luxury.”9

Despite his debts, Washington continued to purchase wine, ale, furnishings for Mount Vernon, slaves, and finally, the topmost image of a planter’s status. The emblem of wealth in Virginia was the coach, or “chariot,” “the unchallengeable emblem of a planter of the highest affluence,” as Douglas Southall Freeman calls it.10 The chariot carried exactly the social status message of a modern automobile. A Virginia merchant wrote to England, “our Gentry have such proud spirits, that nothing will go down, but equipages of the nicest & newest fashions. You’ll hardly believe it when I tell you that there are sundry chariots now in the country, which cost 200 Guineas.”11 In June 1768 the Washingtons were in need of a new coach. To his agents in London Washington wrote, “My old Chariot havg. run its race.… The intent of this Letter therefore is to desire you will bespeak me a New one.” He requested that it be a model “in the newest taste, handsome, genteel and light.… To be made of the best Seasond Wood, and by a celebrated Workman.” He had seen a new arrangement of steel springs “that play in a Brass barrel, and contribute at one and the same time to the ease and Ornament of the Carriage,” and he asked for this feature. He liked the color green, as he thought it a color that would not fade and was in addition pleasing or “grateful to the Eye.” But he hastened to add that he would take another color if it was “more in vogue.” He wanted a “light gilding” and other ornamentation “that may not have a heavy and tawdry look.” As a finishing touch he asked, “On the Harness let my Crest be engravd.” He sent along a drawing of the Washington coat of arms to be copied by the engraver.12

Just three months later the coach was shipped to him. The invoice conveys some of the glory of this “new handsome Chariot, made of best materials, handsomely carvd.” There were arches and scrolls; the sides, roof, and back gleamed with polished japanned paint; painted flowers adorned the panels of the doors; the frame glittered with gilt. A green Morocco leather seat, trimmed with lace, cushioned the passengers, whose feet rested on carpeting. The whole interior was sumptuously lined with green and red leather, and the passengers could gaze at the passing landscape through plate-glass windows etched with diamond-cut designs. If they desired privacy, they could snap shut Venetian blinds fashioned with mahogany frames. There was a place for the finishing touch, the ultimate accessory, a postilion—a slave, dressed in livery displaying the family colors, clutching a rail as the carriage bounced along, and ready to leap to the ground and open the door. The cost for the chariot and shipping came to £315 and change.13

Washington’s purchase was a mixture of financial foolishness and confidence. Unlike many other Virginia planters, he had the shrewdness to see that the tobacco trade would eventually destroy him, and he began shifting to wheat in the mid-1760s. In just two years his output of wheat shot up from fourteen bushels per slave to fifty. His profits rose in spectacular fashion, from more than £9 per hand to £20.14

Debt still hung above Washington’s head. He was able, briefly, to wipe out his arrears to his British merchants in 1773 when a sudden death in the Custis family brought him a large inheritance.* But just a few years later he was again among the Virginia planters who owed heavy balances to English merchants. When American debts to English banks and merchants became a matter of negotiation after the Revolution, it was found that Virginians owed almost half of the total American debt, £1.4 million out of £3 million—with George Washington on the list among the largest Virginia debtors.15

In Washington’s ledgers I found frequent entries showing that he bartered with his white tenants when they had no cash to pay the debts they owed him for various goods and services, such as repairs his blacksmiths made on equipment. His tenants paid with eggs, seeds, a cow, a clothes iron, butter, and by providing midwifery to the Mount Vernon slaves. In 1757 Washington noted that he paid seven shillings to “my Negros for Potatos.”16

* * *

We have the image of the Southern planter as a man of leisure, resting in the shade of his porch with a julep in his hand, but that is a character of a later age, and the opposite of George Washington. Washington always took a direct and personal approach to the management of his plantation. Indeed, he loved farming. It provided him the deepest satisfaction, and he wrote about it with feeling:

I think … that the life of a Husbandman of all others is the most delectable. It is honorable—It is amusing—and with Judicious management, it is profitable. To see plants rise from the Earth and flourish by the superior skill, and bounty of the labouror fills a contemplative mind with ideas which are more easy to be conceived than expressed.… The more I am acquainted with agricultural affairs the better I am pleased with them. I can no where find so great satisfaction, as in those innocent & useful pursuits. In indulging these feelings, I am led to reflect how … delightful to an undebauched mind is the task of making improvements on the earth.17

But to attain this honorable and delectable state of delight required struggle and labor. It required most of all a sense of mastery over the land and people, because the earth does not yield up its fruits easily. A Southern writer captured this sense of struggle when she described a woman who ran a farm: “‘Everything is against you,’ she would say, ‘the weather is against you and the dirt is against you and the help is against you. They’re all in league against you. There’s nothing for it but an iron hand!’”18 In Washington’s case, the land was definitely against him. Mount Vernon was hilly, and runoff led to gullying. The top soil was thin, and beneath it lay a stratum of hard and virtually impervious clay. He was farming in a tub that would not drain.

Washington rode through his farms almost every day and imposed on everyone an almost military discipline. A senator joked in 1799 that “the etiquette and arrangement of an army is preserved on his farm.”19 But the reverse may have been true: Washington was to convey his plantation discipline to the army. He was possessed by a rage for order and a horror of waste.

Washington had been personally managing Mount Vernon for less than a year when he received a lesson in slave management that he thought important enough to record in his diary for future reference. On a February morning in 1760 he wrote that he was “Passing by my Carpenters” who were hewing poplar logs for fences. He took note of the stack of finished pieces they had completed the previous day and measured them. Four men, he found, had hewn “only” 120 feet of timber, a figure that struck him as ludicrously low. He asked them when they had begun the day before, and was told ten in the morning. With that reference point in mind, he “Sat down therefore and observd” his men at work, with his watch in his hand, as if he were timing a horse race.20 This is what slaves dreaded. In fact, the crew of carpenters had a special reason for anxiety. Before Washington had taken personal control of Mount Vernon, the estate had been managed by Humphrey Knight, who died in 1758. The carpenters had literally felt Knight’s anger over lax performances, and on that February morning they were undoubtedly wondering if this unfamiliar master might employ the same techniques as his late manager. In one of his reports Knight had written, “as to ye Carpentrs I have minded em all I posably could, and has whipt em when I could see a fault.”21

With the master’s eye on them, the men suddenly set a splendid pace. Washington wrote, “Tom and Mike in a less space than 30 Minutes cleard the Bushes” from around a poplar, cut the poplar into ten-foot sections, and “hughd each their side 12 Inches deep.” He watched as they manhandled the crosscut saw and the heavy logs, until after “one hour and a quarter they each of them from the Stump finishd 20 Feet of hughing.” Based on this observation Washington made a quick calculation: “from hence it appears very clear that allowing they work only from Sun to Sun and require two hour’s at Breakfast they ought to yield each his 125 feet while the days are at their present length and more in proportion as they Increase.” In sum, four men working all day hewed 120 feet of timber when the master wasn’t looking; when the master was sitting there with his watch, each man produced 125 feet of finished timber, a productivity more than four times greater. Washington made note of this number, and it became his benchmark of productivity for the hewers.

Washington headed his annual diary with the title “Where & How my Time is Spent.” Though he kept a careful, almost obsessive accounting of his activities, Washington’s diaries have been a disappointment to biographers. He recorded almost no intimate observations, wrote no reflections revealing of his inner thoughts, and composed no eloquent flights of prose. But the very flatness of the diaries reveals the man—he was practical, hardworking, and demanding of himself and others. Cultivating wheat demanded less personal attention from him than growing tobacco did, and in 1765 Washington hired his cousin Lund Washington to take over many of Mount Vernon’s management duties. One biographer, comparing Washington’s diary entries from 1760 and 1768, thinks he found evidence that Washington began to lead a life of relative ease after he hired Lund to run things: “he was spending a considerable part of his time … in foxhunting, shooting, fishing, and visiting.” His life did get somewhat easier—he spent several days in August 1768 foxhunting, relaxing at home, and attending horse races—but in the previous month he had spent twenty-two days supervising the cradling of wheat, the hay harvest, and planting.22

He personally examined the wheat crop on July 4 and found it too green to harvest and stopped the hands. The next day he hired a white harvester named Palmer to inspect the wheat and tell him if it could be safely cut. This aspect of farming was obviously a tricky business that Washington did not feel competent to judge himself, hence he needed Palmer’s opinion. Then Palmer, three white men, and four slaves began to cut at Muddy Hole farm. Washington kept an eye on them and noted, for future reference, the output of the hands: “six and sometimes 7 cradlers, cut the remainder of the field (abt. 28 acres) on this side to day.” Another day he wrote, “Three White men (Cradlers) cut down abt. 10 or 12 Acres.” He liked Palmer and decided to hire him to work with his carpenters at coopering. A certain amount of dickering went on between these two farming men. As part of their deal Palmer asked Washington to buy his wagon, and Washington wrote in the agreement that he would take the wagon “if it is no older than he says.”23

Washington’s work life at Mount Vernon had a routine sameness that did not bother him in the least. He wrote, with contentment, that “the history of a day … will serve for a year.”

I begin my diurnal course with the Sun;… if my hirelings are not in their places at that time I send them messages expressive of my sorrow for their indisposition—then having put these wheels in motion, I examine the state of things farther.… By the time I have accomplished these matters, breakfast (a little after seven oclock …) is ready. This over, I mount my horse and ride round my farms, which employs me until it is time to dress for dinner.24

Washington was a man of regular habits, and he expected his workers, white and black, to exhibit similar discipline and good order. In a seven-page directive to a manager he wrote,

To request that my people may be at their work as soon as it is light—work ’till it is dark—and be diligent while they are at it can hardly be necessary, because the propriety of it must strike every manager who attends to my interest, or regards his own Character, and who, on reflection, must be convinced that lost labour is never to be regained—the presumption being, that, every labourer (male or female) does as much in the 24 hours as their strength, without endangering their health, or constitution, will allow of.25

To be at work “as soon as it is light” required that the slaves arise in the dark, before sunup, and walk in the dark to their assigned places. There was no time for breakfast, which came later. Washington also began work before breakfast. The slaves were expected to work until the sun went down, and then walk home in the dark. During the workday they had a two-hour break. In the summer months, the slaves put in a workday of fifteen to sixteen hours, six days a week.

Washington kept a close eye on his white overseers as well, and coached them in the basics of management. He sought to inculcate the habit of forethought in them, directing that if an item needed to be carted some distance immediately, then do it, but if something else would have to be carted to the same place the next day or the next month, then carry both of them at the same time and save a trip. “These things are only enumerated,” he wrote, “to shew that the Manager who takes a comprehensive view of his business, will throw no labour away.” His injunctions could be boiled down to two basics: use your head and always be at your job:

Forethought and arrangement which will guard against the misapplication of labour, and doing it unseasonably: For in the affairs of farming or Planting, more perhaps than in any other, it may justly be said there is a time for all things. Because if a man will do that kind of work in clear and mild weather which can as well be done in frost, Snow and rain, when these come, he has nothing to do; consequently, during that period there is a total loss of labour.… be constantly with your people. There is no other sure way of getting work well done and quietly by negroes; for when an Overlooker’s back is turned the most of them will slight their work, or be idle altogether.26

Washington took direct control of his Mount Vernon estate at a time when British agriculture was about to undergo a modernizing revolution. A passion for improving agriculture extended to the height of British society—it was chic to be concerned with the muck of farming. George III, who became king in 1760, began to maintain his own experimental plots at Windsor Castle. He wrote articles on agriculture (published with his farm overseer credited as the author). The English agricultural scientist Jethro Tull promoted the use of manures, advocated pulverizing soil with horse-drawn plows, suggested planting crops in rows so that cultivating machinery could move more easily among the plants, and devised a drilling device to set seeds at regular intervals. Washington adopted all these methods.27

He displayed a remarkable grasp of the farm as a complex system, an interlocking organism made up of land, climate, livestock, crops, equipment, and labor. Part of this grasp was probably intuitive, but he also gained insights from other Virginia planters, notably his good friend Landon Carter. Both Washington and Carter took a scientific approach to plantation management. Carter wrote an observation that either man might have made: “This world has somehow been established upon the principles of number, weight, and measure.” Washington was averse to anything that was “slovenly but easy,” and he wrote, “I shall begrudge no reasonable expence that will contribute to the improvement & neatness of my Farms … for nothing pleases me better than to see them in good order, and every thing trim, handsome, & thriving about them; nor nothing hurts me more than to find them otherwise.”28

When Washington shifted from tobacco to wheat in the 1760s he had to make numerous changes at Mount Vernon. He understood the fundamental but complex relation that large-scale cultivation required large numbers of draft animals, which required large amounts of fodder, which in turn required new crops and a new landscape at Mount Vernon. This he set about in methodical fashion to create. He drained swamps to create new fields, where he planted the usual corn fodder, but also experimented with other forage crops such as lucerne, timothy, sain foin, clover, and burnet. With his draft animals provided for, he could conduct his cultivation with plows rather than with men and women wielding hoes. He had to schedule the plantation’s seasonal activities with care, lest one ripening crop go to waste while another was being tended. His hay had to be cut, for example, at the same time the wheat was ripening. By abandoning tobacco Washington freed up time and labor because tobacco required constant attention whereas wheat and corn did not. The dividends in time and labor he invested in new crops of grain, peas, potatoes, and grapes. Another dividend ripened—an increase in manure, which Washington collected and plowed back into his fields.

The new modes of agriculture at Mount Vernon created a need for new skills, and it also created a new pattern of work assignments. Women worked in the fields at some of the worst, most distasteful tasks that required less skill, such as gathering and spreading manure, clearing stumps from swamps (a task with the evocative name of “grubbing”), cleaning dirt from grain, building fences, cleaning stables, and breaking up ground with hand tools in places where the plows could not go. About 65 percent of the working field slaves were women, and Washington was demanding and punctilious in his instructions for them. He wrote to a manager: “when I say grub well I mean that everything wh. is not to remain as trees should be taken up by the roots; so … that the Plow may meet with no interruption, and the field lye perfectly smooth for the Scythe.” The menfolk meanwhile handled the plows, harrows, and wagons, sowed and cut the grain, and dug and maintained ditches. The job of ditcher, which I initially took to be a low-level task, was actually considered a skilled position.29

In reviewing Washington’s records, I was surprised to come across evidence that Washington knew his field slaves individually. I had assumed that when he gave orders in the fields he would address himself to “you there!” or “you, the fellow with the red scarf, yes, you!” But Washington’s own words offered such detailed descriptions of four of his slaves that we can actually get the sense of gazing at their faces. He obviously observed these men closely, because he wrote these descriptions from memory:

Peros, 35 or 40 Years of Age, a well-set Fellow, of about 5 Feet 8 Inches high, yellowish Complexion, with a very full round Face, and full black Beard, his Speech is something slow and broken, but not in so great a Degree as to render him remarkable.

Jack, 30 Years (or thereabouts) old, a slim, black, well made Fellow, of near 6 Feet high, a small Face, with Cuts down each Cheek, being his Country Marks, his Feet are large (or long) for he requires a great Shoe.

Neptune, aged 25 or 30, well set, and of about 5 Feet 8 or 9 Inches high, thin jaw’d, his Teeth stragling and fil’d sharp, his Back, if rightly remember’d, has many small Marks or Dots running from both Shoulders down to his Waistband, and his Head was close shaved.

Cupid, 23 or 25 Years old, a black well made Fellow, 5 Feet 8 or 9 Inches high, round and full faced, with broad Teeth before, the Skin of his Face is coarse, and inclined to be pimpley.30

The most remarkable features are the scarring and filed teeth of two of these men—marks of their birth in Africa. The series of cuts on Jack’s face and the network of dots cut into Neptune’s back had meanings that Washington did not understand, but he took careful note of them. In fact, Neptune and Cupid had been brought to Virginia from Africa only two years before Washington wrote these descriptions in 1761. Washington noted that “they talk very broken and unintelligible English.” Jack had been transported from Africa several years earlier and spoke “pretty good English.”

Washington wrote the descriptions because these four men had run away. In August 1761 he placed an advertisement in the Maryland Gazette describing the men and offering a reward for their capture. The men had run away on a Sunday and had apparently planned their escape for that day of the week. Three of them disappeared wearing Sunday clothes, such as the “dark colour’d Cloth Coat, a white Linen Waistcoat, white Breeches and white Stockings” that Peros wore. Sunday being a day off for slaves, the four escapers would not have been missed until nightfall or the next day; and the sight of four men walking down a road in good clothing would not have aroused much suspicion because many masters allowed slaves to leave the plantation on Sundays to visit relatives or trade in Alexandria.

Washington knew Cupid well because Cupid had been deathly ill with pleurisy about a year and a half before running away, several months after his arrival from Africa. On his daily tour of inspection Washington had come upon him in bed and instantly realized the seriousness of his illness. He ordered that Cupid be carried in a cart to the main house “for better care of him” and personally checked on Cupid’s condition during the day and evening, writing in his diary, “when I went to Bed I thought him within a few hours of breathing his last.” Cupid recovered, but any gratitude he may have felt toward his owner for the care he received was outweighed by the desire for freedom. (Years later, a Mount Vernon house servant whose life was saved by costly medical care also subsequently laid plans to escape.) These four men represented about 10 percent of Washington’s labor force: in 1760 he had forty-three slaves over the age of sixteen at Mount Vernon. All together the four runaways were probably considered to be worth about £200. Having grown up with slaves, Washington had carefully observed their patterns of behavior and he thought he could predict their moves. He wrote in the advertisement:

As they went off without the least Suspicion, Provocation, or Difference with any Body, or the least angry Word or Abuse from their Overseers, ’tis supposed they will hardly lurk about in the Neighbourhood, but steer some direct Course (which cannot even be guessed at) in Hopes of an Escape: Or, perhaps, as the Negro Peros has lived many Years about Williamsburg, and King William County, and Jack in Middlesex, they may possibly bend their Course to one of those Places.

From Washington’s words it would seem that slaves often ran off after a punishment or confrontation to “lurk about in the Neighbourhood” until they had cooled off and decided to return. But because nothing untoward had happened with these men Washington suspected they had planned their escape to an area that Peros or Jack knew well, where they could possibly lose themselves in a free black community. He was probably trying to protect his reputation as a master when he insisted that there had been no abuse.

Peros might have been the leader of the escape. He spoke English fluently. His “yellowish Complexion” suggests that he was born in America of mixed-race parents—he was a Custis slave who had come to the Mount Vernon plantations after Washington’s marriage, and he had spent many years in and around Williamsburg. That town had a community of free blacks who were notorious for helping runaways.* Two things Washington said about him are revealing. In the first place he said that Peros was “esteemed a sensible judicious Negro,” a phrase that expresses his surprise at the sudden flight. Washington thought he understood Peros from his sensible and presumably docile demeanor; in fact he knew nothing. He presided over a community of consummate actors.

Secondly, Washington noted that Peros “speaks much better than [the others], indeed has little of his Country Dialect left.” But that means that Peros had some of his “dialect” left—this American-born, mixed-race slave had retained enough of his African language, probably from a parent, so that he could communicate with Neptune and Cupid, who spoke only “very broken and unintelligible” English. This vignette reveals a great deal about the slave community at Mount Vernon: newly arrived Africans mingled with African-Americans; some could barely speak English, and some bore the cultural marks of their homeland, scars and filed teeth that may have made them seem exotic to the American-born slaves. Even so, the Africans and African-Americans made common cause and laid elaborate plans together.

The escape did not succeed. All four men were recaptured and brought back to Mount Vernon. Washington did not record how this came about, though he noted an expense for “Prison Fees in Maryld Neptune.” His papers do not reveal the ultimate fates of these men. One by one, over the years, they simply cease being mentioned in Washington’s records. They might have run away successfully, or died.32

Why did these men run away in the first place? Was Washington’s regime a harsh one? How hard did his slaves work? From the records, I tried to get a sense of the amount of work done by George Washington’s slaves. His diary entries are laconic, and it is impossible to get a sense of the difficulty of the slaves’ lives from them. In an entry for February 1762, for example, he noted plainly, “Began Plowing for Oats.… Sowed a good deal of Tobo. Seed at all my Quarters.” In March he wrote, “Finished Plowing for Oats—abt. 20 Acs.… Began Plowg. and Ditchg. the Meadow.… began Sowing & Harrowing in of Oats.… grafted Six trees in the Garden.… Burnt Tobo. Beds.” Mixed in with these entries were equally spare accounts of disasters, such as: “a prodigious severe frost…’tis to be fear’d the Seed all perished.”

But at certain times of the year he entered cumulative tallies that give some sense of the scale of work he expected to be done. I did some simple arithmetic on these figures, and came up with numbers I found hard to believe. At his plantation in King William County in April 1763 he recorded the making of 190,000 corn holes and 170,000 tobacco hills.33 His roster for that farm listed just fifteen slaves with two overseers—which meant that each slave made 24,000 hills and holes. This number seemed impossible. I sent out a query to Washington experts, one of whom wrote back to say, “If you set 24,000 plants in 30 days (800 per day), you would have to drop about one per minute average for 12 hours. That is not very strenuous work for farmers.”34

But this arithmetical answer did not seem sufficient. It turned out that the administration of the Mount Vernon estate today was itself wrestling with this question, at the plantation’s Pioneer Farm, which attempts to replicate Washington’s farming techniques. I contacted the woman who supervised the farm, Jinny Fox, to put the question to her. She said that if I wanted to get an idea of the working lives of Washington’s slaves, she would have to put some old-time tools in my hands and set me to work in the field. It seemed like a straightforward exercise in hands-on research.

* * *

A school bus disgorged a gaggle of middle-school children as I arrived at Mount Vernon’s main gate on a cold, slate-gray day in January. Jinny Fox led me from the main gate and up the path in front of the mansion. I had seen it many times, but it remained an impressive, stirring sight. On that overcast day, its whitewashed presence seemed even larger and more imposing. It was 10:00 a.m., and it occurred to me that the master of Mount Vernon would have been out for hours by that time of morning, on his daily tour of inspection. He would have been casting his sharp, commanding eye over the very tasks Fox had in mind for me. I did not think I would want to see the figure of George Washington, astride a horse, suddenly looming over me as I wielded a hoe.

As Fox led me down a side path toward a corral, I asked what had brought her to Mount Vernon. She had grown up in California, where the schools had emphasized the region’s Spanish history and barely touched on the Revolution. George Washington was little more than a distant historical figure in a powdered wig. But an interest in history led Fox to volunteer at Mount Vernon as an interpreter in the “hands-on history” tent, where staffers demonstrate eighteenth-century farming and cooking techniques for the tourists. She brought a great deal of enthusiasm to the task, and after two years as a volunteer she was offered a job. For a year her assignment was to don a period costume and interpret the character of Elizabeth Washington, wife of George Washington’s cousin and farm manager, Lund Washington.35 Then she moved to the Pioneer Farm, and when the supervisor resigned, Fox was offered his position.

We stopped at the corral, where several horses munched contentedly. One of them was in fact a mule by the name of Kit. Fox explained that Washington was the first person to breed mules in America, sterile beasts that are a cross between a male donkey and a mare. Kit and his equine cousins were on winter break from their duties in Washington’s treading barn, where their task was to walk in endless circles, trampling wheat stalks to separate the grain from the chaff. “He was very particular about how they would be taken care of,” Fox said. “He didn’t want his mules used until they were at least three years old, and then he wanted them broken in gradually. He recognized the importance of taking good care of the livestock.”

The introduction of mules was just one of Washington’s agricultural innovations. Fox ticked off a few of his other achievements: “He rotates crops—first he tries buckwheat and later switches to clover … He builds the first dung repository in America to compost manure … He tries to reclaim marshland for meadows … He plants root vegetables as an experiment in cultivation … Experiments with feeding his livestock better and buying better sheep to breed. These were major agricultural experiments. His problem was the land wasn’t very good to begin with. By the time Washington inherited this land it was pretty well exhausted. Even the additional land that he bought had been farmed for about one hundred years.” She pointed out that on the fresher fields of central Virginia to the southwest, “Jefferson was able to grow tobacco for thirty years more than Washington.”

I mentioned that the diary entries from the 1760s showed that Washington spent more and more time at his favorite sport of fox-hunting and less at actually managing his farms. Fox quickly sprang to his defense.

“I think that Washington’s character was set in stone from day one. Even though he might have been foxhunting a lot, he’s got one eye on the farms. He was hunting over the territory where he had farms, and he’s watching what’s going on.”

She added that Washington personally supervised tobacco planting and the extensive fishing operation on the Potomac. “What people don’t realize is that the planters of tobacco were just as involved as the slaves. They were the artists. They knew exactly when things had to be done. They knew when the tobacco worms were going to appear, when the tobacco fleas were going to appear. And he watched over the hauling of the seines. In 1761 they pulled 1.5 million shad and herring out of the river in three weeks. That was a major enterprise he had to have his hand on, to make sure the fish were packed in salt quickly. They would gut them, take the heads off them, and wash them in a bath of brine, then they would pack them with rock salt and seal them in barrels. Washington set aside twenty fish per slave per month as an allowance, and then the rest was sold.”

We stopped at a structure that looked exactly like a rough-hewn outhouse, except that it had a small fenced-in area in front where two chickens pecked at the ground. I hesitated to speculate why chickens would be ranging around an outhouse, but I had been misled by my ignorance of agricultural architecture.

“It’s a chicken coop. We’re trying to figure out if the chickens will survive; because if they do then we can bring in some of the rare breeds.”

“Survive?”

“The foxes. It looks like we’re down three chickens. I hope that’s not a bad sign.” She leaned over the chest-high fence to address the chickens directly. “I don’t know if they’ve moved three, or if you guys are down three because somebody’s gotten the rest of you.” But we didn’t see any feathers that would indicate the depredations of a predator.

“You grow used to the fact that livestock dies,” Fox remarked as we descended a path through some woods and over a footbridge to the behind-the-scenes part of Mount Vernon.

I asked her what the slaves would normally be doing at this time of the year.

“In January they’d be chopping ice off the river, burning brush, hauling and cutting wood.” The Pioneer Farm closes from December to February each year because the weather is too cold for the school groups. “The months in the winter are valuable to me because that’s when I go through the records with a fine-toothed comb.”

We descended into a ravine to a trailer by a dirt road. This was Jinny’s headquarters in the woods. Inside she had an array of sickles in an overhead rack. Mallets and hoes with rough-hewn handles stood in a corner. A table was spread with miscellaneous hand tools and a cardboard filing carton that held a batch of long, slender wood shavings that looked like the makings of a basket. There was a large crosscut saw, sticks of various shapes and sizes that had been smoothed by long use, and underfoot here and there, wooden buckets coopered on the place.

Jinny pulled out a foot-long, heavy board embedded with nasty spikes. This was a hackle for shredding flax into strands that could be woven. She produced a wad of tangled flax, which she pulled through the hackle with her right hand while resting her left hand on the spikes to keep the hackle in place—a method I thought could shred her palm if she wasn’t careful. I noticed she kept a bottle of antiseptic nearby.

As Jinny was demonstrating this risky procedure, her associate Mike Robinson came in. An archaeologist, Robinson split his time between Mount Vernon and Gunston Hall, the restored estate of Washington’s friend George Mason, another of Virginia’s eminent founders. Tall and bearded, Mike had the look of a genuine pioneer farmer.

The two of them rooted among the tools to select the right implement for me. Mike suggested the auger, used for digging post holes. “It’s the most daunting tool,” he said, but then he had a second thought: “We don’t want to catch his finger.” Jinny concurred: “I took out a quarter inch of flesh on that.” Mike rummaged around again and came up with a froe and a mallet. I had never seen or heard of a froe, which sounded medieval and looked something like a hatchet except that its long, narrow blade was hung upside down on the handle and slid loosely up and down its length.

Jinny offered me an eighteenth-century-style woolen waistcoat, of the sort, Mike said, “worn by middling farmers.” A slave would never have such a warm and comfortable garment for this raw January weather. Carrying our selection of eighteenth-century tools—froe, mallet, a pair of hoes, and a flail—we set off for the work shed.

Modern Mount Vernon has built a long shed where interpreters can display the typical tasks of an eighteenth-century farm. For nine months of the year this area swarms with tourists and school groups, but on this off-season day we had the place to ourselves. In front of the shed was a pile of straw. Jinny stepped over to the pile and began thumping it with a flail—two sticks, one long and one short, attached with leather straps. Jinny held the longer stick in a modified baseball-bat grip, with her hands apart, and swung hard so that the shorter, heavier stick mashed the straw. This was one method of threshing. Jinny handed the tool to me and I took a series of enthusiastic swings. Instantly, the tedium of the task became obvious—the same motion in the same place in endless repetition. I could not imagine doing this from the early dawn to the late dusk of a summer day.

Jinny led the way to a three-walled room in the work shed with a pair of rough-hewn contraptions whose function was not at all clear at first glance. She sat down at one of them, straddling a plank and placing her feet on a treadle underneath. A wooden bar, linked to the treadle, immediately snapped down in front of her. I was grateful that I had not sat down first because I would naturally have rested my hands on the precise spot where the bar slammed down. This was a coopering bench, which functioned as a large, man-powered vise. The cooper places a piece of wood on the shelf in front of him, steps on the treadle, and the bar snaps down to hold the wood firmly in place while the cooper shaves it into a stave. Jinny said they invited an old-time coopering expert from Nebraska to do a day of demonstrations. He said that in the old days coopers were apprenticed as early as age seven, and by the age of fifteen could turn out seven buckets a day.

The companion machine was a marvel of ingenuity—a lathe powered by a cut sapling that acts as a spring. The worker sits at the lathe, pushing a treadle. The treadle is attached by a rope to the sapling, fastened horizontally to a post behind the operator and extending over his head to the front of the lathe. Each time the worker pushes the treadle the sapling is pulled down; when he releases the treadle the sapling springs back into place, spinning the lathe. Mike said that the lathe was a vital machine for any farm estate because it was used for making handles, and “the handles for tools were particularly important because somehow they were always breaking.” I commented that this “machinery” looked so antique and quaint—the perfect props for a Currier & Ives scene. Jinny responded, “With all the repetition it loses its charm.”

They took me to the adjacent part of the shed, where I finally learned what a froe was for. Mike bent over a block of cedar, rested the blade near an edge of the wood, and tapped the froe with his mallet. The blade gently dug into the wood. Mike slipped the handle down a bit, gave the blade a twist, and with a splitting sound a neat sliver of cedar fell to the ground. “There’s one shingle,” Mike said. This is how roofs got made, one shingle at a time. Mike handed the tools to me, and I felt the pleasure of working with a tool perfectly suited to its task. I tapped and twisted, and soon had a small pile of shingles to show for my effort. I finished and leaned the froe against the block of wood, with its blade down, realizing quickly I was doing the wrong thing. I asked Mike how to put the tool away. “Would you put the froe on the ground with the blade down? Or would that dull it?” Mike replied, “That’s what a slave would do.”

His remark stunned me since it was so gratuitously insulting. Then Jinny jumped in and filled in the logic. “If it’s dull you don’t have to work. Wouldn’t it be a shame if you came down here first thing in the morning and you found your blade was too dull for you to work?” Mike added, “How long would it take you to find another one?”

Now I realized the implication of Mike’s earlier remark about tool handles always turning up broken. Jinny called it “passive resistance”—random and petty sabotage, malingering, tools missing and broken, rampant theft.

“Sheep are disappearing, wool is disappearing, grain is disappearing,” Jinny said. “Washington is running himself ragged trying to stop it—lock this, lock that, only cut out enough fabric for one garment when you give it to them.” Jinny had been reading the letters from Philadelphia written by Washington when he was president to his then manager at Mount Vernon, William Pearce. From Pearce’s reports Washington had deduced that the slaves had figured out a way to steal wool without detection. It was his custom to allot to the slaves the dirty, least valuable portion of the wool at shearing time. “The best wool is from the back of the sheep’s neck down his back,” Fox explained. “The stomach wool was allowed the slaves because that’s where all the vegetable matter and manure gets absorbed. Washington, who has figured out exactly how much wool he should be getting from these sheep, finds out that he is getting about two or two and a half pounds of wool instead of five pounds per sheep.” When the slaves took their allotment of the fouled stomach wool, they were surreptitiously helping themselves to a large portion of the good wool.

To make matters worse, the shearers would toss some of the dirty stomach wool in with the batches going to the spinners at the mansion. The spinners were under orders, naturally, not to spin dirty wool. So when they received their allotments every week, they set aside the bad wool for themselves. In this manner, the thieving rippled through the Mount Vernon system. Washington, with his eagle eye, detected it from his meticulous reading of the weekly reports: “I perceive by the Spinning Report of last week, that each of the spinners have deducted half a pound of dirty wool. —to avoid this in the future (for if left to themselves they will soon deduct a pound or more) it would be best to let them receive none but clean wool.”

The slave women at one of the Custis plantations that Washington had to manage from a distance were expert negotiators, and they took full advantage of the communications confusion that resulted from the master and mistress’s absence. The overseer on that plantation wrote with exasperation to Washington in 1772 that a spinner had filled a quota of wool and stopped working, claiming that Mrs. Washington had agreed that three pounds a week of wool would be sufficient. Another slave refused to spin at all because Martha had agreed that she only had to sew, another because she said her only job was watching the children. The slaves had no qualms about refusing the overseer’s requests, saying that Mrs. Washington did things differently. Confused and vexed, the overseer wrote to Washington to ask what Martha wanted done.36

Nails disappeared by the barrel; the stable boy was stealing the horse feed; Washington figured that half of his pigs were being stolen; and so much seed was walking off that Washington ordered the seed to be mixed with sand so it would be too bulky and heavy to steal. He railed against “the deception with respect to the Potatoes.”37 Washington went mad with frustration when he observed his wagoners at “work”:

There is nothing which stands in greater need of regulation than the Waggons and Carts at the Mansion House, which always whilst I was at home appeared to be most wretchedly employed—first in never carrying half a load; —2ndly in flying from one thing to another; and thirdly in no person seeming to know really what they did; and often times under pretence of doing this, that and the other thing, did nothing at all.

He complained that the wagons seemed to go off and “go to sleep.” He watched as the carters pulled tiny loads they could carry on their backs, while his bricklayers stood idle because the carters hadn’t delivered any bricks to them.38

From reading Washington’s letters Fox came to a not-so-startling conclusion: “He obviously doesn’t trust black people.” I reminded her that Washington trusted several black men enough to make them overseers. “But they’re picking him clean,” she replied. “He was infuriated by Davy, whom he described earlier as being one of the best overseers, because the lambs were disappearing.” She mentioned another slave named Isaac, one of the few slaves whom Washington allowed to have a gun for hunting. Isaac lost his hunting privilege when his carelessness with fire was thought to have caused the burning of the plantation’s carpentry shop.

Washington struggled with his white overseers as well. When he was away from Mount Vernon during his presidency, the overseers drank and lazed about. “There was a man named Crow whose idea of overseeing was to entertain guests in his house, so he was never out in the fields,” Jinny said. Naturally, the slaves simply stopped working. Jinny said that Washington found out about Crow’s work habits from the slaves, “because when things fell behind Crow would pull out the whip.” The slaves knew that Washington disapproved of indiscriminate whipping, so they complained to him. Jinny mentioned another overseer, Thomas Green, who was in charge of Mount Vernon’s carpenters. He, too, did almost nothing, but he was able to get away with it for a long time.

“Green was smart. He let the slaves do what he did. They were getting drunk with him and they were not doing any work, but they weren’t going to report on Green because Green wasn’t whipping them. They had a sort of pact going, and that’s what frustrated Washington. Washington wrote that the slaves under Green did nothing. He said it would take them longer to build a chicken coop than it would take the same number of carpenters in Philadelphia to build an entire house.” But Washington worried that the man who replaced Green, James Donaldson, would prove equally unreliable. “He did not want Donaldson living with the slaves because he was afraid that Donaldson would corrupt them if he’s a drinker. So his view of overseers isn’t a whole lot better than his view of slaves.” Washington gave Donaldson strict, almost military instructions not to get too familiar with his subordinates.

In his struggle to control his slaves Washington had to resort to violence. He regarded physical punishment as a necessity. But he also knew it was necessary to restrain his overseers in wielding the whip. “The overseers were supposed to petition him if a slave needed punishing. It was supposed to be written down why,” Jinny said. He knew that Crow was a violent man—the slaves had told him—so when it became necessary to have a slave whipped, he sent instructions to Pearce to have it done, “but do not trust Crow to give it to him.”39 The issue of the whip forced Jinny to confront the morality of Washington’s regime. “It’s easy to say ‘the overseers whipped the slaves.’ But if Washington gave permission, he might as well have wielded the lash.”

Fox had begun her close reading of Washington’s letters and farm reports to reconstruct the reality of a working plantation as accurately as possible, but she was coming on something more valuable, a view of Washington’s inner life, of his decades-long moral struggle with slavery. She found clues to it in many places, even in something as mundane as the weekly “sick bay” report from his manager. She found accounts of people who, with no clear excuse, did not show up for work for days on end. She noticed that Washington was often inclined to give these malingerers the benefit of the doubt. “Washington, being a fair enough individual, will entertain the idea that there might be a legitimate cause, which is amazing.” He would direct the manager to visit the slave personally, examine him, and determine if a doctor’s attentions were warranted.

This response to the thieving and malingering at Mount Vernon intrigued Jinny Fox. “He railed against it but didn’t stop it. I think he could have stopped it. I think there were slaveholders who successfully stopped a lot of things, but they did it in a way that would have been unacceptable to Washington. If you keep people’s flesh torn into shreds you can eventually break their spirit, or kill them. But that’s where Washington stands out. I really like the man’s character. He was a man with a keen sense of fairness and rightness. What’s remarkable about Washington is there seems to be something carved out inside of him that is distinctly different.” Yet as soon as Fox expressed this feeling about Washington’s fair-mindedness, she qualified herself: “But he is a slave owner, and there’s no way to sugarcoat that.”

There is a particular incident in Washington’s slaveholding career that is hard to sugarcoat. Some of his famous false teeth, celebrated in textbook lore, were yanked from the heads of his slaves and fitted into his dentures. Moreover, Washington apparently had slaves’ teeth transplanted into his own jaw in 1784, in a procedure that did not succeed. At first, this seems to be the ne plus ultra of casual plantation cruelty; but Washington paid his slaves for the teeth, and the custom of the wealthy buying teeth from the poor was common in Europe. The dentist who performed the procedure at Mount Vernon was an itinerant Frenchman who transplanted teeth for many well-to-do clients, including acquaintances of Washington. It has long been known to specialists that some of Washington’s false teeth came from the mouths of his slaves, but this inherently invidious tidbit of fact has not been widely circulated (despite enduring public interest in Washington’s supposedly wooden dentures, which were mainly made of ivory) because it is impossible to rationalize it completely. Better not to know.40

* * *

I was standing at the edge of a field, staring at the dirt. Behind me, within running distance, flowed the Potomac River. In Washington’s time the river carried a constant commerce of ships of all kinds. That view would surely have tantalized the slaves. The ships headed downstream were destined for the Chesapeake and the Atlantic, on routes to places where slavery did not exist. How many slaves imagined the run to the riverbank, a frantic swim to a passing vessel, a helping hand to pull a man aboard and take him away? In the history of Mount Vernon such a day came only once, and not exactly in that form. During the Revolution a British warship dropped anchor here, demanding supplies and offering passage to any slaves who wished to flee. Seventeen men and women scrambled aboard.

Jinny and Mike put a hoe in my hand and started me chopping at the clay. They explained that this earth had been plowed so often it was far softer than the hard clay the slaves would have confronted on an average January day. I was hoeing at a pretty brisk pace when Jinny began chanting a song.

Juba this, Juba that

Juba killed a yellow cat.

She timed her chant to my motions, and then began to slow down. I slowed down too, without thinking about it. She said that was how the slaves managed their own work: a leader would chant, setting a tempo that everyone could keep up with; if the overseer came into view, the leader would speed up, and once he departed the chant would slow down again.

I told Jinny and Mike that I had read that in one planting season, a slave would make more than 11,000 tobacco hills, and I asked them what that meant. Jinny took the hoe and pantomimed making a hill—the reality would have covered her with mud. A slave would set one foot on the ground and then hoe up the earth around it, heaping it against his or her leg—both men and women did this work—all the way to the knee. Then the slave would carefully lift out the leg, and the resulting hole, in a two-foot-high hill, would receive a tobacco seedling. Doing this several hundred times a day had to be one of the most arduous and filthy labors on a farm.

“They must have kept a frantic pace in planting season,” I said. “There was probably no break for bad weather.”

“Actually, tobacco planting is better in bad weather. The optimum time to transplant seedlings is in the rain, when they will have a better chance of surviving. They often planted tobacco in driving rainstorms. That’s when you need to do it. You’d have one slave tending one to three acres, and you have three to five thousand holes per acre. The labor of tobacco was just tremendous, mind-boggling.”

Mount Vernon’s modern farm raises patches of tobacco and wheat, so visitors can get a sense, at any time of year except midwinter, of what kind of agricultural work was actually going on in Washington’s time. And they can actually participate in the work. This “living history” approach to interpretation had been used for more than eighty years at other historic sites, but it was not inaugurated here at the Pioneer Farm until 1999.

“We had this pat little thing we did about hoecakes,” she said. When visitors came to the fields they would find a costumed woman cooking a cornmeal cake on a hoe held over a fire. The visitors would be invited to have a bite of hoecake to give them a sense of how the slaves lived. “We would talk about the food the slaves ate and mention that they worked in the field and that would be it. We wouldn’t get into any controversy. We had a lot of irritated, frustrated people who wanted to know the other side of the story. They wanted to know: What were the slaves doing? What were their lives like? And we were saying”—she mimicked in a jaunty tone—“‘Oh, well, they got a quart of cornmeal, they got some salted fish.’ You’re almost making a mockery of what happened. It’s a flippant approach. And it came off as Washington being ‘good,’ and that bothered me. It isn’t that I want Washington to be bad. It’s that I want people to understand what slavery was.”

By trying to depict the lives of the slaves with some authenticity, Jinny Fox tumbled into the moral maze of slavery. The simple matter of re-creating a colonial farm scene had a paralyzing moral effect. Up North, ersatz Pilgrims can hoe and scythe all day long at Plimoth Plantation with no moral ambivalence, but in the South, simply to depict the working lives of slaves, without making any overt moral judgment, is to call the “goodness” of Washington into question.

“We began implementing the hands-on program because we wanted to produce a sense of what slavery really was, particularly for the groups of kids who come. If you do the work you begin to grasp the labor. In March, when it’s still freezing here, they have an idea of what it’s like to dig clay, cut rails, and split them. Anybody can do that in April and May, but they don’t like to do it in March. Then, on a hot May day, cutting three bunches of wheat gives you a real idea of what it might be like cutting sixty acres. Only you get to quit. You can stop. It’s hot. I don’t want to do this anymore. But the slave is going to be there from five o’clock in the morning until the sun goes down.

“We raise about fifty tobacco plants per year and the kids are allowed to do a number of things with the plants. During the course of the year you have to sucker it, pull the worms off of it, watch it every day so that at the peak of ripeness you’re going to be cutting it. Those plants are sticky; the leaves are covered with little hairs. When the kids handle those plants, we tell them to visualize about five thousand plants that they’re responsible for, passing through every other day, checking for the worms.

“We work on a one-third-acre field. Sixty acres was the smallest of Washington’s fields. He had fields of 120 acres. Imagine now, every six feet, another row of corn running the whole length of that acreage. And the only way to get the weeds out because of heavy rain is by hand. I can tell you, last summer, in our little, tiny one-third of an acre—and we didn’t do it all day long because we rotate around—it took us four weeks to clear the weeds out. Once the vetch gets in there, you can weed it and two days later it’s back up again.

“I don’t know how people did it. I like hard work. I love working with my hands, I love being outdoors. But what if I were compelled to do that? What if the best I could hope for my child was that he might be light-skinned enough and clever enough to attract the attention of the master and be made a house servant rather than a field hand?” Promotion to “the big house” meant a somewhat easier life, but the enslavement continued. Perhaps the hardest thing about slavery was the eternity of it, to work in the fields and to see your children and grandchildren working beside you and know that this will be their life forever. There is never going to be any way out.

Next to the field where the work is demonstrated Jinny had a shed built where visitors can try grinding corn and taking part in a game the slave children played. Each day the slaves had two hours off at midmorning to make and eat their breakfast, and while the adults prepared the food the young ones played. Under the shelter (which the slaves actually would not have had), a table was set up with a large pestle with two long handles for crushing corn into meal. Jinny showed me how two people would stand at the mortar and methodically drop in the pestle, to a chant, to grind the day’s corn. It takes about an hour to grind a cup of cornmeal, which is what they needed for a day’s ration. This was a task the slaves actually wanted to do. It was part of their tradition. Washington wanted to give cornmeal rather than whole corn because it was easier to measure accurately and it saved time; but the slaves wanted the whole corn, and Washington reluctantly agreed. One reason the slaves wanted corn kernels instead of meal was that they were sharing their ration with their chickens.

Mount Vernon’s archaeologists have been surprised at the variety of food remains they find in the foundation of the House for Families on the estate. “They were allowed to hunt and fish,” Jinny said. The few slaves who were allowed to use a gun to hunt for Washington’s table were hunting for their own food as well. But there was a time of year Jinny called “the starving season—the time when the meats are going bad, and there isn’t the fresh game and the crops are not in yet and the vegetables the slaves were allowed to grow were not up yet. Probably between March and June.” At that time of year poorer people, white and black, free and slave, were struggling to get enough food.

At another table under the shed Jinny and her staff have visitors play a plantation game, with four players standing around the table, sliding sticks to one another as someone chants. Players pass the sticks in time with the chant, which speeds faster and faster: the point of the game is to keep up the pace because the person chanting will stop abruptly, and you lose if you have two sticks in front of you. On a plantation, this game was meant for the littlest ones, slaves just three or four years old. The elders designed it so the children would learn as early as possible the rules of the slave life that awaited them: you need to work in unison with others; you need to keep up; if you fail to keep up, you’ll get in trouble. Slave parents taught their children how to be slaves. They did not teach them to run away or fight back, which would have been suicidal; they taught their children how to survive. In the fields and in the mansion, the psychology of slavery was self-perpetuating.

Our final stop was Washington’s threshing barn, an edifice far more interesting than its name implied. I did not think of Washington as an inventor, but his constant striving for efficiency led him, even in the midst of discharging the duties of the presidency, to take up a pencil and sketch out plans for an inspired piece of agricultural innovation. This new kind of barn was essentially a machine the size of a small building, where wheat would be threshed by horses and mules. The original barn stood until the 1870s, when it had to be torn down. In the 1990s Mount Vernon reconstructed it, based on Washington’s original drawings and a glass-plate photograph taken about 1870. Round in appearance, the barn is actually a sixteen-sided polygon under a steeply pitched conical roof. (The caplike roof gives the barn a distinctly African appearance.) Jinny led the way up an earthen ramp to a wide opening. When I entered the barn I realized that I was on the second floor of a two-story structure. The lower floor, below grade, could not be seen from the front.

The slaves would haul the wheat up the ramp and spread it on the second-story floor to a depth of several feet. Then horses and mules would be brought in to trot around the circular floor, separating the wheat from the chaff under hoof. Washington had the inspiration to design this floor with gaps, so that the grain fell to the granary level below. He had his carpenter experiment with gaps of different widths to attain the perfect spacing that would allow the grain to fall through freely without letting straw fall along with it—a gap of 1.5 inches was found to be ideal. Once the grain had tumbled into the lower granary, there it would remain, safely stored, until wagons brought it to Washington’s mill. The slaves would haul out the chaff, pile it up outside the barn, and begin the process again. It was an elegant solution to several problems, and to see the reconstructed barn today is to admire Washington’s ingenuity.

Like so many aspects of plantation life, this barn had a subtext. Washington was inspired to build the barn after a long tug-of-war with the slaves over how threshing would be carried out at Mount Vernon. Washington wanted the slaves to thresh indoors on a threshing floor, so that rain would not ruin the wheat and so that the grain would not get mixed with dirt and then require time-consuming cleaning. For this purpose he originally built a one-story threshing barn, large enough to accommodate twenty to thirty threshers. But the slaves had their own agenda. Rather than flailing away at the wheat themselves, they preferred to have the horses do it for them; nor did they like the tasks of hauling the wheat into the barn and the straw out of it. The easiest way to thresh was still the old-fashioned way: to pile the wheat up in the field (as Mike remarked, “there are no doors in a field”) and lead the horses over it. If the master didn’t like it, too bad.

When Washington came to inspect the workers at his first barn, he found, to his astonishment, a threshing circle set up outside the barn. The slaves had simply ignored the building and spread the wheat on the ground, as before, and had set the horses to walking on it, as before. Washington knew when he was beaten. But from this defeat arose his inspiration: he would find a way to get the horses indoors. The result was the ingenious two-story design with its carefully creviced floor.

Over all, however, Washington’s attempts to increase efficiency, improve quality, and attain better profits were always hampered by the slave system. The slaves (and, to a great degree, the overseers) did not share his vision or his drive because they could never share in the results. Washington never quite grasped this idea because he had been brought up to be indifferent to what his inferiors thought and felt. He sensed the slaves’ resistance to innovations, and it merely made him angry. Any innovation, he found, had to be very simple to be comprehensible to his overseers and slaves. A new type of English threshing machine caught his interest, but he despaired of getting any use out of it “among careless negros and ignorant Overseers,” noting with sarcasm, “if there is anything complex in the machinery it will be no longer in use than a mushroom is in existence.” Even a relatively simple device such as a new version of a plow would be of no use to him; he had learned “from repeated experiments, that all machines used in husbandry that are of a complicated nature, would be entirely useless … and impossible to be introduced into common use where they are to be worked by ignorant and clumsy hands, which must be the case in every part of the country where the ground is tilled by negros.”41

* * *

Washington kept in his mind a simple formula as the governing principle of his life as a planter. Late in life he wrote it down in a letter to a manager. On his plantations he sought “tranquility with a certain income.”42 A great deal is expressed in this formula. Washington, like other planters, did not seek to be harsh or brutal; he wished for tranquillity. This is an eerie echo of a phrase in the Preamble to the Constitution, which states that the people ordain the Constitution to “insure domestic tranquility.” That tranquillity was brought about by government and by the consent of the governed. Similarly, slaves had to accept government. They were not expected to consent, merely to acquiesce and to cooperate. The result would be “a certain income” for the owner. Tranquillity made the economic part of the formula possible, but the tranquillity of the plantation was entirely superficial, as it rested upon the constant threat of violence. The plantation could not function in turmoil and constant violence, so an atmosphere of harshness prevailed because economy always trumped human concerns. It is interesting that, unlike Jefferson, Washington never instituted a system of rewards for slaves who performed well; he expected that they would do their duty and that he owed them nothing extra.

In 1785 Washington had a conversation with a slave that shows how he kept his financial equations in mind. It was harvest time, when every man, woman, and child was needed to bring in the crop, so Washington was dismayed to spot someone not working. The man had injured his arm, which was in a sling. Washington thought that having the use of only one arm need not prevent a man from working, and he proceeded to demonstrate to his slave how to rake with one arm.

He grabbed a rake with one hand and tucked the other hand in his pocket. He then raked, saying to the slave, “Since you still have one hand free, you can guide a rake. See how I do it: I have one hand in my pocket and with the other I work. If you can use your hand to eat, why can’t you use it to work?”43 This man, though injured, was still consuming food. The one good hand that scooped up food could handle a tool.*

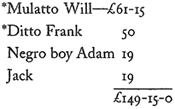

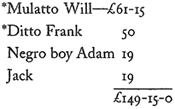

Another of Washington’s basic equations expressed Virginia’s governing economic principle: slaves equal land, and land equals wealth. The more slaves you had, the more land you could settle and cultivate. Washington spent about £2,000 buying slaves before 1772, but he ceased making purchases in that year. In July, making one of his last purchases, he wrote to the man who was carrying a consignment of Mount Vernon’s flour and herring to the West Indies: “The Money arising from the Sales I would have laid out in Negroes, if choice ones can be had under Forty pounds Sterl[ing].” He specified what he wanted: “If the Return’s are in Slaves let there be two thirds of them Males, the other third Females—the former not exceeding (at any rate) 20 yrs of age—the latter 16—All of them to be strait Limb’d, & in every respect strong & likely, with good Teeth & good Countenances.” He was thinking about Mount Vernon’s future; he wanted teenaged slaves, including girls with a long period of childbearing ahead of them. Washington was growing laborers as if they were a crop, to make himself self-sufficient as a slave owner. The results of his planning are clear. Between 1760 and 1774 the number of his taxable slaves more than doubled from 49 to 135.44

The function of the slaves in Washington’s financial equations—and the casual callousness of those equations—emerges clearly in the story of the slaves Nancy and London. In 1773 he dispatched these two slaves from Mount Vernon to a farm he was starting in western Pennsylvania. He had to begin cultivating it in order to reduce the taxes on the land—uncultivated land was taxed at a high rate to encourage settlement and to discourage holding land empty for speculation. Large landowners, such as George Washington, who was in fact engaged in a long-term real-estate investment, found it necessary to “settle” land with a small number of slaves, whose labor insured his investment.

Washington had a partner in this operation, Gilbert Simpson, who lived on the place. As his part of the bargain Washington sent the two slaves to clear the land and get a crop into the ground. Clearing virgin forest was perhaps the hardest of all farming tasks, requiring brute strength and a great deal of endurance to bear up under that labor for months at a time. Washington sent a crippled male slave and a house girl. They were useless to him at home, but they could earn their keep clearing distant land. The man named London was lame because he had lost some of his toes to frostbite. Washington knew well the extent of London’s lameness—he could not even walk with ease, let alone perform hard labor. Washington himself wrote to Simpson, in explaining London’s merits, that the loss of his toes “prevents his Walkg with as much activity as he otherwise would.” But on the positive side Washington adjudged London to be “a good temperd quiet Fellow,” meaning he was docile and would not disrupt the tranquillity of the operation.

As for Nancy, Washington knew she had a large family at Mount Vernon, which he later alluded to in a letter to Simpson, saying that they would be delighted to see her. When he sent her off from her family, Washington described Nancy as “a fine, healthy, likely young Girl which in a year or two more will be fit for any business—her principle employment hitherto has been House Work.” So Nancy was little more than a child who had done housecleaning. Simpson described the work he had for them. He said he had never carried out harder work, and wrote, “the cutting is vastly heavy occasioned by the great number of old trees lying on the earth.”

After putting London and Nancy to work for several months cutting and hauling enormous trees, Simpson was blunt in his report to Washington: “you furnish me with two hands as sorry as they could well be. The fellow is a worthless hand and I believe always will be so,” partly because of his lazy nature and partly “occasioned by his feet.” As for Nancy, “she knew nothing of work but I believe she will make a fine hand after two or three years.”45

Washington’s overriding concern with labor efficiency led him to divide his slaves in a way that greatly weakened their families. Later in life, he expressed great concern for the slave families, refusing to break them apart by sale and in his will expressing great anxiety lest families be broken up after his death. But he showed no concern for keeping families together day by day. He routinely separated husbands from wives and fathers from their children.46

Washington divided the Mount Vernon estate into five separate farms—an important management arrangement for the slaves. Every farm had its own slave quarters, which meant that the slave community was divided into five parts. Waste of any sort appalled Washington, and nothing irritated him more than wasting time. If he had only one central slave quarters, then the workers would expend valuable time “commuting” to work at outlying fields. As he wrote, he was determined to avoid losing “much time in marching and countermarching.” But he needed the more skilled workers, who were male, at the main house, so the result of his division of laborers was that many families lived apart—husbands at the “Home Farm,” wives and children on the outlying farms.

Washington was certainly aware of this effect when he formulated his work plans. The list of slave families he drew up as an appendix to the will shows that half of the married men at Mount Vernon did not live with their families. Thirty-two of the married women did not live with their husbands. In only eighteen families did husband and wife reside together. On one of the outlying farms there was not a single intact family. From time to time Washington responded to individual pleas and rescinded orders that would have separated spouses; but as a general management practice he institutionalized an indifference to the stability of the slave families.47