Chapter 16

The Conscience of the World

Even the most barbarous savages would have been ashamed at the obscene treatment the Germans meted out to Jews and other minorities. The history of the world contains no analogies to such brutality. As more and more details of the German death-factories became public, the civilized world slowly emerged from its lethargy and rediscovered its conscience.

The Pope energetically protested at the persecutions. Religious houses and other Church organizations struggled to lend their help, particularly on behalf of Jewish children. The Red Cross supplied food and medicine to the most needy. Still, all this help was no more than a drop in the bucket.

Even Regent Horthy tried, somewhat belatedly, to ease the situation, providing certificates of immunity to eminent Jews who in the past had performed special services for the upper echelons of society. These documents exempted their recipients from the fate awaiting other Jews and at least nominally restored them to their position in the community.

One evening, when I returned to our room I found Ozma putting the finishing touches to a letter he was planning to send to the Regent. He read it to me.

My response was blunt. ‘I’m opposed to all exceptions, but if you insist on asking the Regent for an exemption, don’t beg. Be forceful, and keep your tone cool and direct. That way, you won’t one day feel ashamed of humiliating yourself.’

I believe Ozma never did send his petition. If he did, it was not granted, since he stayed with me and continued to live as he had before.

Several European and Latin American neutral states with embassies and consulates in Budapest started issuing certificates of immunity to Hungarian Jews, whom they lodged in buildings across the city rented for the purpose. In due course the Swiss, Swedish, Spanish and other nationalities established such safe houses. Ignoring the chance that they would be picked up while standing in line – from dawn to dusk – outside the consulates, petitioners were willing to risk deportation at the very moment of their potential salvation. Soon a black market in certificates of immunity grew up: if the owner of a certificate needed money, he could always sell it and go back and stand in line again. This was also a great opportunity for forgers, and the market in forged documents grew particularly lucrative. Soon the situation became so confused that even the people in the embassies could not say whether a given certificate was genuine or false. The hectic struggle to obtain such documents came to an abrupt end when the Nazis hauled all the inhabitants of a couple of the safe houses away to the Danube and drowned them in the river. Their bodies floated downstream.

For my part, I remained firm in my disapproval of this mode of protection: first you catch the Nazis’ attention by pinning a yellow star to your chest and then you pull out of your pocket a certificate of immunity and wave it in their faces! The most rational approach, in my view, was complete separation, followed by a quiet effort to blend in with the general population. That is the way animals do it: when they sense danger, instead of presenting a clear target to their enemies, their natural mode of self-preservation is to blend with the scenery and simply disappear. Naturalists call this phenomenon ‘mimicry’. Whenever friends or clients approached me to help them obtain certificates of immunity, I tried to talk them out of it and advised them to follow this other route.

Tivadar Soros with his sons and father-in-law, 1931

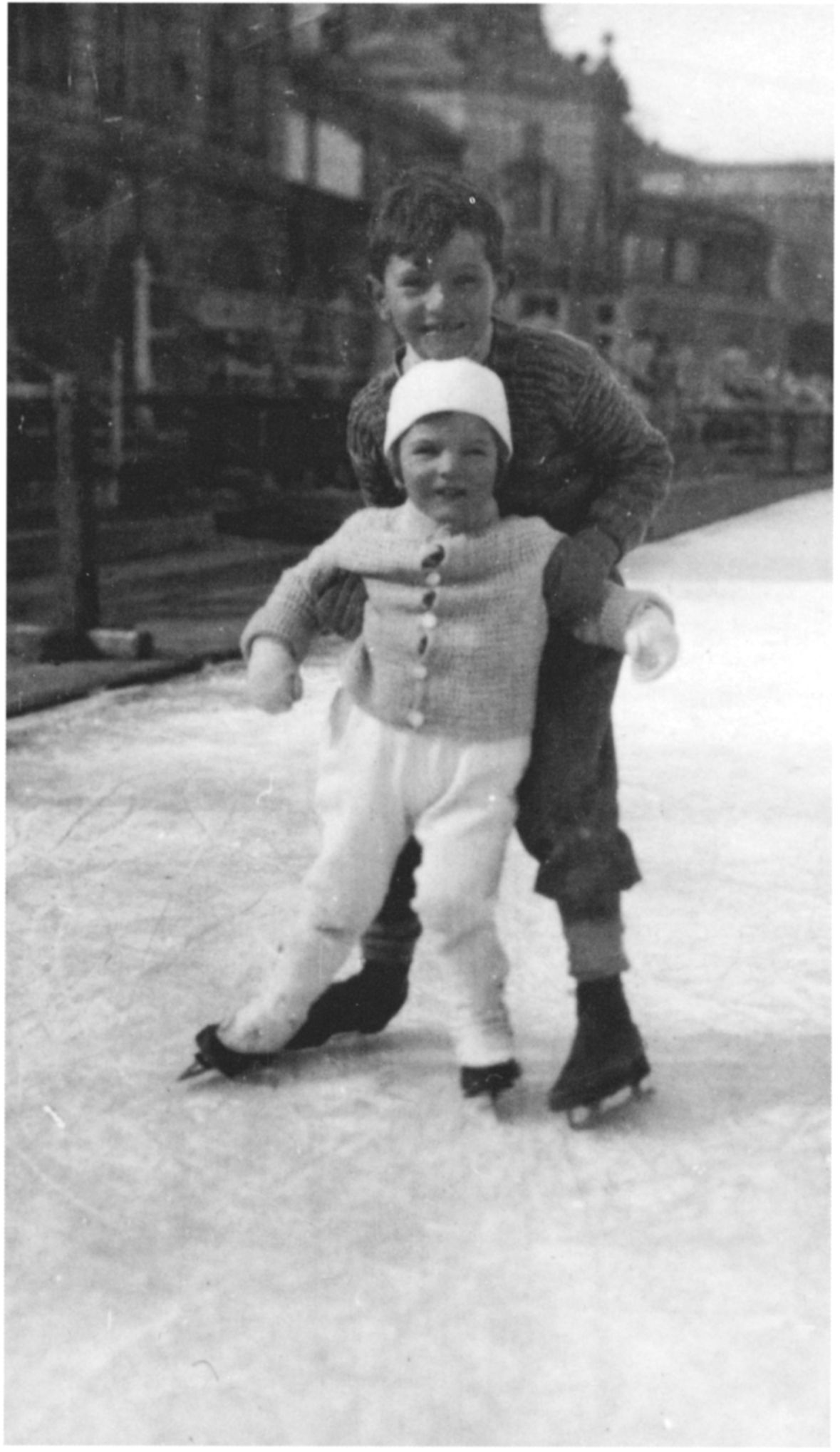

Tivadar Soros with his sons, 1933

Paul and George, 1934

Tivadar Soros’s mother-in-law who was rescued from the ghetto as a young girl

Mother-in-law with George, 1931

Tivadar Soros’s wife, Elizabeth, and Paul, 1927

Skiing in Austria, 1930

Summer life in peace, 1932

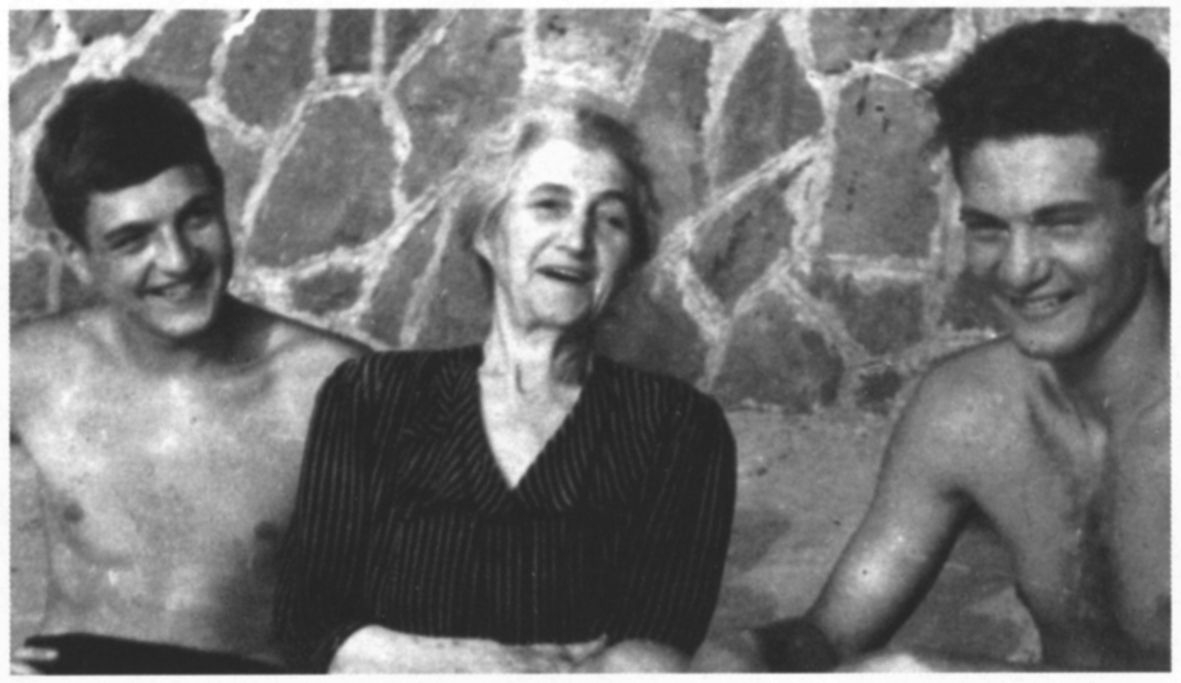

George, grandmother and Paul, 1943

Paul, 1940

George before going to school in England, 1946

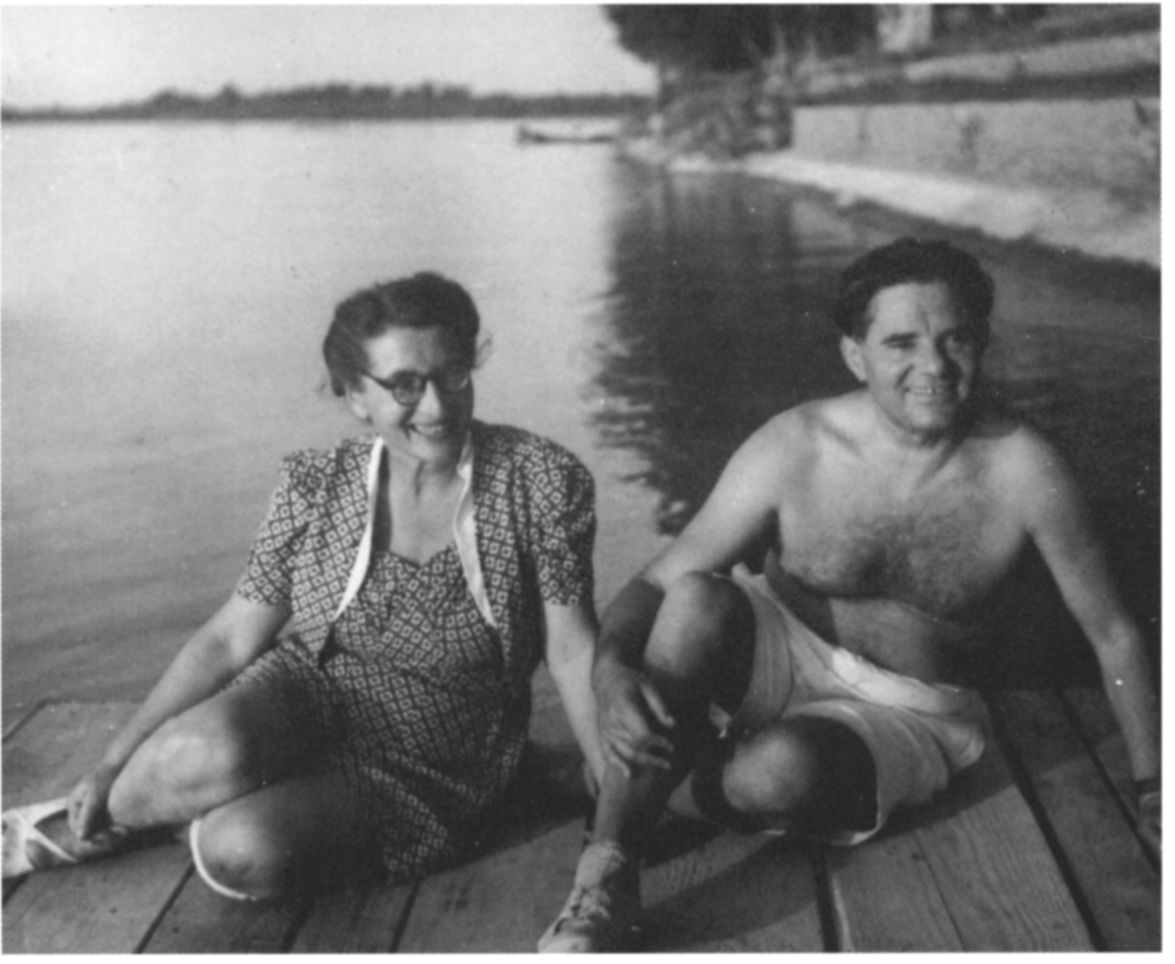

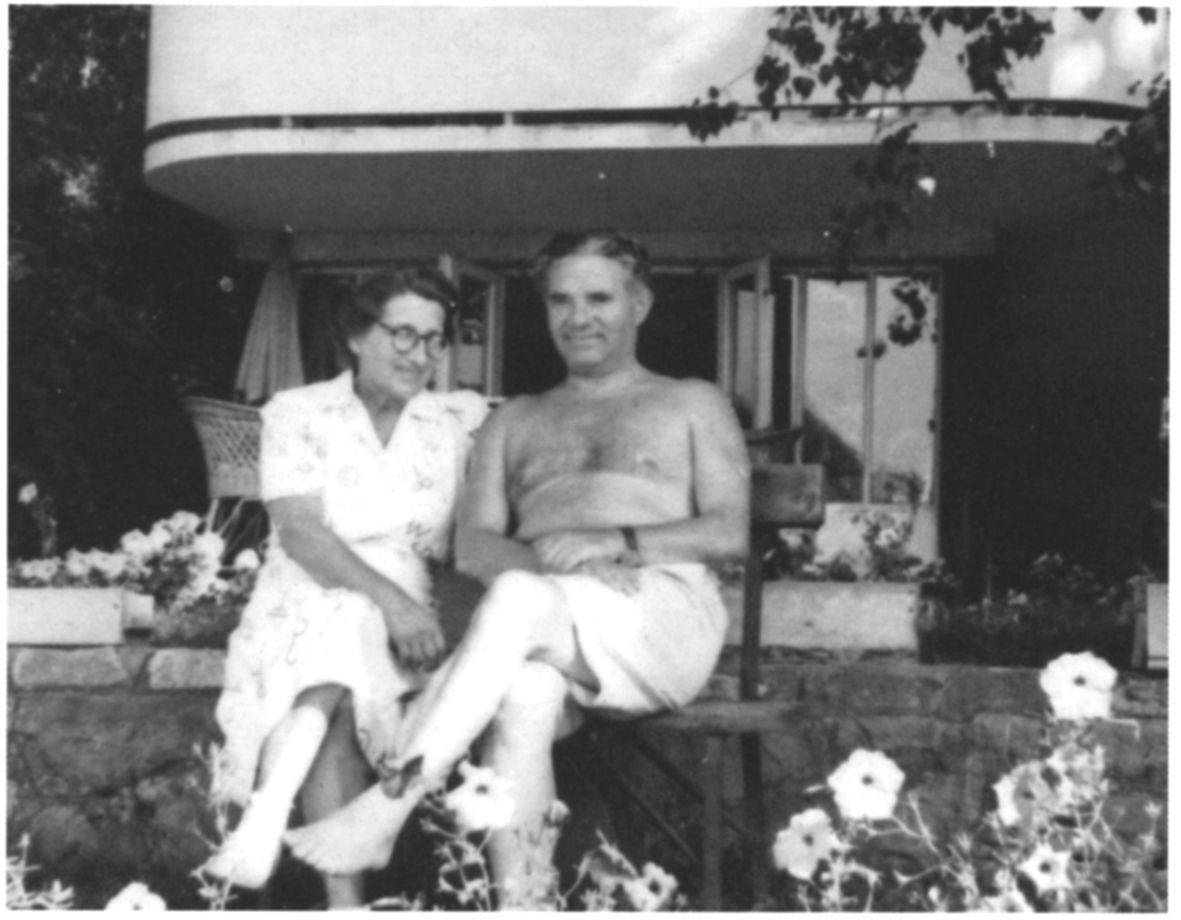

Tivadar and Elizabeth Soros at the summer house after Paul escaped from Hungary, 1948

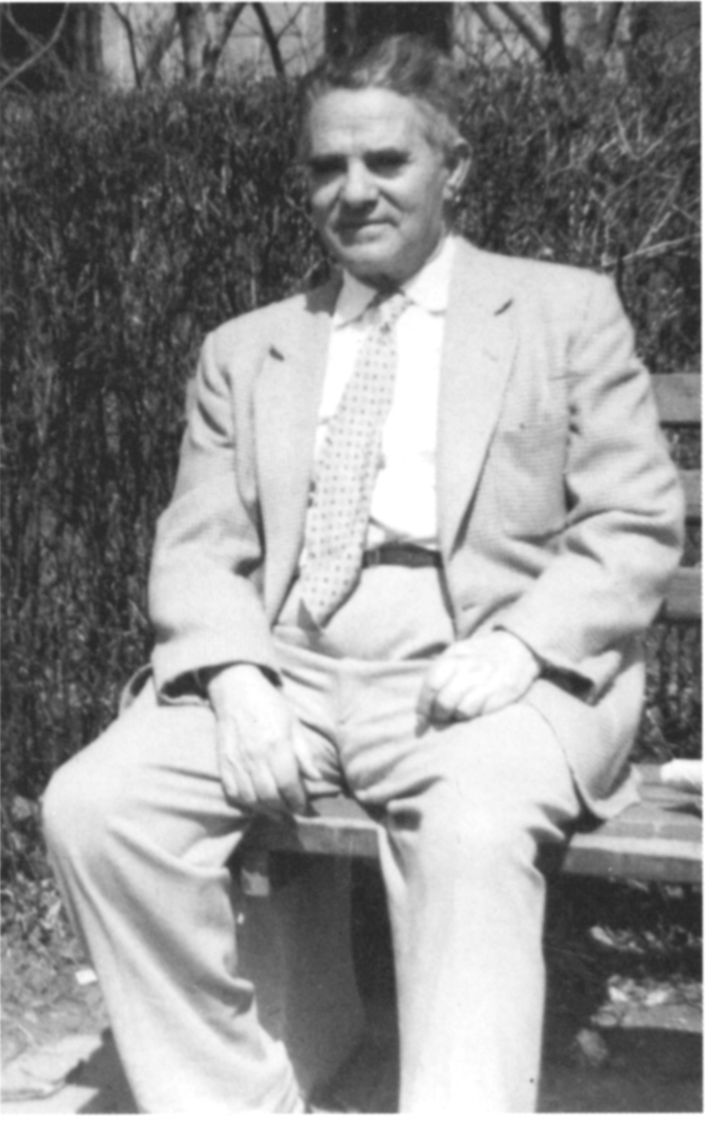

Tivadar Soros in the last year of his life, 1968

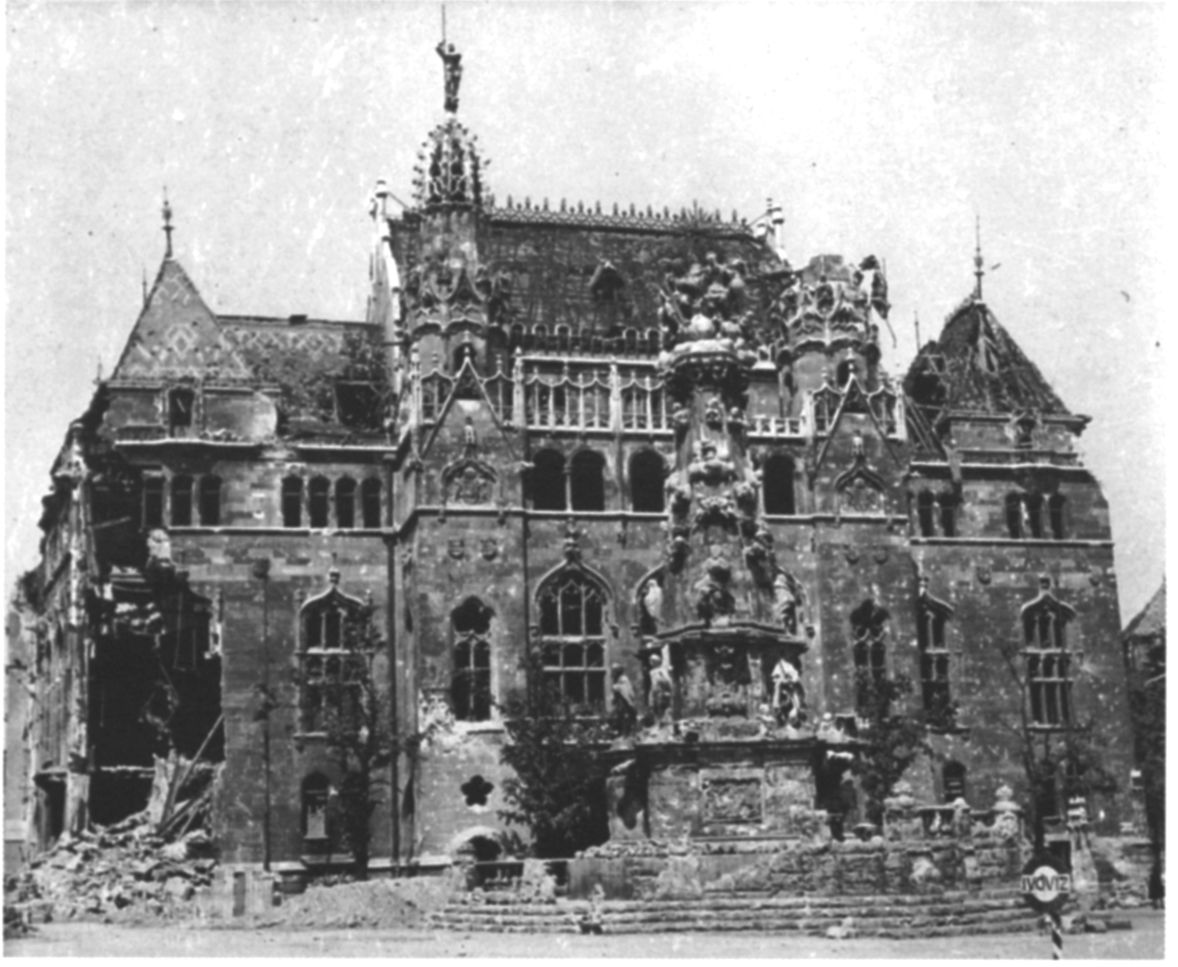

War-scarred Budapest By kind permission of Associated Press

Tivadar and Elizabeth Soros at the summer house, 1952

From time to time we heard about other successful modes of escape. The Chorin and Weiss families, major industrialists, saved themselves, their dependents, and apparently part of their possessions by formally giving up title to their industrial holdings, and transferring them to Göring Industries, the German company in the hands of Hermann Göring. This chance of escape arose because of the intense rivalry between Göring and Himmler: Göring saw the acquisition of this industrial giant as a way of strengthening his position against Himmler and he was right. The deal was very much to his advantage: the entire arrangement cost nothing, beyond the preparation of thirty-five or forty official passports allowing the ‘vendors’ to emigrate from Hungary.

Then there was a group of some 1,600 Orthodox Jews and Zionists who camped in a temple yard, guarded and protected by the SS. Needless to say, it was hard to evaluate the nature of such protection. One of my uncles was a member of this group, along with his entire family. He admitted having paid a huge sum – several hundred thousand pengős – for the ‘good fortune’ of belonging to the group. Later I found out more about this ‘business transaction’ from Emi.

Emi was no ordinary girl. Her striking appearance, forthright opinions, and sharp sense of humor revealed a firmness of character but a somewhat enigmatic disposition. One summer day I waited for her, as we had agreed, at the streetcar stop outside the Rudas Baths. She failed to turn up. Over the years I had grown accustomed to the fact that women who don’t work have a rather imprecise sense of time, so I patiently sat there on a bench, lost in my thoughts. Suddenly a voice startled me.

‘You’re Elek Szabó, right?’

Looking up, I was surprised to see in front of me a rather unpleasant-looking military policeman. How did he know my name? He wore a chain around his neck, with a serial number. I hated even looking at one of these bloodhounds. I nodded to indicate that I was indeed Elek Szabó and waited to see what would happen next.

‘I have a message for you. Miss Emi sends her regards and wishes to inform you that she will be delayed until ten thirty.’

And he saluted smartly and departed. That was our Emi! Finding no one better, she simply sent a message by one of the military policemen from the detachment assigned to guard the Danube bridges. I was aware of the fact that her psychic equilibrium was not always quite normal. When she was twenty-two she fell hopelessly in love with a forty-year-old man who was in the middle of a divorce. They were not able to meet very often because he had been drafted into the Labor Service. She used all her considerable energy to keep him supplied with packages of food, so that he would not go hungry.

I did my best to explain to her that the art of living involves balancing a sense of responsibility against one’s personal feelings.

‘Emi, you’re a sensible woman. Don’t you realize the uselessness of being tied to Joska? There are plenty of intelligent, attractive young men closer to your own age.’

‘If you must know,’ she replied angrily, ‘I happen to prefer older men. If you weren’t married and I didn’t know your wife, I’d fall in love with you too.’

‘Very flattering.’

‘Don’t get any ideas. It’s not that I find you particularly physically attractive, but you do always seem to have time for me when I want to talk to you. For example, this situation with Joska,’ she sighed. ‘Love is not some kind of rudder: you can’t just turn it and head off in a different direction. Maybe I should admit to you that it’s not really feelings of intimacy that draw me to him, but respect and honor. Stuck in the Labor Service, Joska is so beaten down and hopeless that I have no wish to make his life any more miserable than it is already. It would be cruel to abandon him now. It would take away his last hope: he’d simply fall apart.’

I was ruminating on this conversation when at 10.30 she appeared. What a pleasure to see such radiant features! Only people with very delicate skin seem to shine in this way. Her eyes sparkled, and her voice was wonderfully appealing as she came up to me and greeted me.

The greetings over, she came straight to the point: ‘I’ve come to say goodbye. I’ve made a decision.’

‘What now?’

My voice showed no surprise. She was forever changing her mind.

She explained that Sándor Csillag, the son of one of the board members of the Jewish Council, had fallen in love with her. She thought he was nice, but that was about the extent of it. His father had arranged for him, and also for her, to be included in the list of Jews whom the SS would transport to Switzerland. This group had been assembled from among Zionist and Orthodox Jews as a result of negotiations by Kastner and Brand with Adolf Eichmann, head of the Nazi commission for the extermination of Jews.

Eichmann was a strange figure, a total thug who boasted of having exterminated millions of Jews in occupied Soviet territory and elsewhere. To broaden his knowledge of things Jewish, he had actually learned Yiddish and Hebrew. But now, with the German army’s recent failures and its steady retreat on all fronts, the liberation of Europe from the Nazis seemed only a matter of time. So he now regarded the Jews primarily as a commodity to be traded as profitably as possible, while they were still alive, rather than killing them and, with typical Teutonic thoroughness, turning them into soap.

‘Emi, use your head. Can you really trust the SS?’

‘Of course not; but where’s the guarantee that I’ll live if I don’t join the group? I can tell you confidentially that the Jewish Council has been in touch with a German Jew inside the SS and he has assured the council that the Eichmann crowd are perfectly serious about wanting to sell the Jews for dollars.’

Her reply made it quite clear that she had made up her mind: she was going where she felt she had some support. We said farewell. She turned – and had taken perhaps ten or fifteen paces when she suddenly ran back and kissed me on the cheek. I never saw her again.

And what happened to the group? They, including Emi, were transported to the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, where they stayed for several months. It was only after the end of the war that I learned that Eichmann and his crew, eager to prove to the foreign Jews with whom they were negotiating that they did indeed have control of Jewish lives, diverted to Austria two trains on their way to the Auschwitz extermination camp with three thousand Jews on board. These Jews survived the Nazi regime. This aside, the 1,600-person group at Bergen-Belsen was the only group allowed to cross to Switzerland, after protracted negotiation with the Jewish community in Switzerland over the ransom to be paid. A large part of the ransom, paid by each individual in the form of jewels and other valuables, had in fact been given to the Eichmann gang by the group’s leaders before the departure from Budapest.

So, if we were doing a balance sheet on all of this, clearly the negotiations with the SS had the positive result of saving some 4,500 Jews from certain death in the extermination camps. But on the other side of the ledger we would have to note a much larger negative: the Jewish Council’s voluntary collaboration with the authorities, combined with the ignorance of the Jews themselves, facilitated and indeed enabled the deportation of several hundred thousand Jews from Hungary to Germany. None of this could have happened without voluntary collaboration on the part of the Jewish Council.

Yes, Emi reached Switzerland successfully. She became a university student. Six months later, just short of her twenty-third birthday, she killed herself. I do not know why. Perhaps she could not endure the torment and confusion surrounding her relations with Joska and Sándor.

Later I heard about another escape attempt – a truly bizarre example of lack of forethought. One day a pilot called on a former bank director. He explained that he had a completely trustworthy contact who, in return for a large enough bribe, could secure a plane for him. Apparently two high-up people had guranteed that they would make a plane available in return for some huge sum of money. He planned to fly the plane to Cairo and could take ten people, if they were willing to pay the required amount. Preparations for the flight were begun in greatest secrecy. The price for each passenger was fixed at 200,000 pengős, which could be paid in goods (jewelry, works of art and so on) or in cash. A ten-person group ready to fly to Cairo was quickly assembled. Then, one night a limousine with curtained windows arrived to take the group to the airport.

The organizer, providing everyone with a map of the route to be followed, explained, ‘I have to warn you of one thing. Magnetism is so strong in the plane that delicate and high-quality watches will certainly get broken if they’re not specially protected. So we’re taking a special anti-magnetic capsule with us, and we recommend that you all give us your watches for safe-keeping in the capsule.’

They duly did as they were advised. With these careful preparations completed, and after half an hour of zigzagging back and forth on city streets, they arrived at the supposed airport. As soon as they stepped out of the curtained limousine, they realized to their horror and consternation that they had been tricked: they had been driven to the Detective Center at Svábhegy. Lest there be any doubt about the fact that this was the Detective Center and not the airport, they were all viciously beaten. This center was where the planning was done for the shipment of deportees to the extermination camps in Germany.

The group was then loaded into a truck for the journey to the collection point on Rökk Szilárd Street. But, by an amazing stroke of good fortune, the truck was involved in an accident at the intersection of József Boulevard and Rökk Szilárd Street: the truck overturned and everyone was thrown out into the street. One of the people in the group was Elza Hös, a well-known and highly popular film director, who immediately realized that she had a chance to escape, particularly since her home was just a minute’s walk away and she knew the area well. In this whole unhappy sequence, the accident was a kind of miraculous turn of events at exactly the right moment: she and several others were able to escape the claws of the mass-murderers. Dragging her elderly and dazed mother with her, she ran into a nearby coffee house and was able to escape.

When Elza Hös told me about this unique yet in some sense typical event, I could not contain myself. ‘Elza, you’re a smart woman. How on earth could you be so naive as to allow yourself to fall for such an obvious trap?’

‘The plan seemed so carefully thought out. The preparations were so thorough.’

‘But any child could tell you that there’s no airplane in Hungary that could fly non-stop from Budapest to Cairo. That in itself should have removed any doubt from your mind that this was a put-up job.’

‘I’m sure you’re right,’ she agreed after a moment’s thought; ‘but I was so eager simply to climb in a plane and get out of here that I was ready to go along with even the most risky of ventures.’

Desire guides and rules mankind, says the poet, and he’s right. If we want something enough, the brain loses its ability to check the facts and our reason and logic get befuddled. Ultimately, we can’t even see straight. I’ve become convinced of this over the years through observing my own behavior, having on many occasions judged situations too optimistically, rather than prudently analyzing all the facts and looking at what could go wrong rather than what might go right.