.......................................................

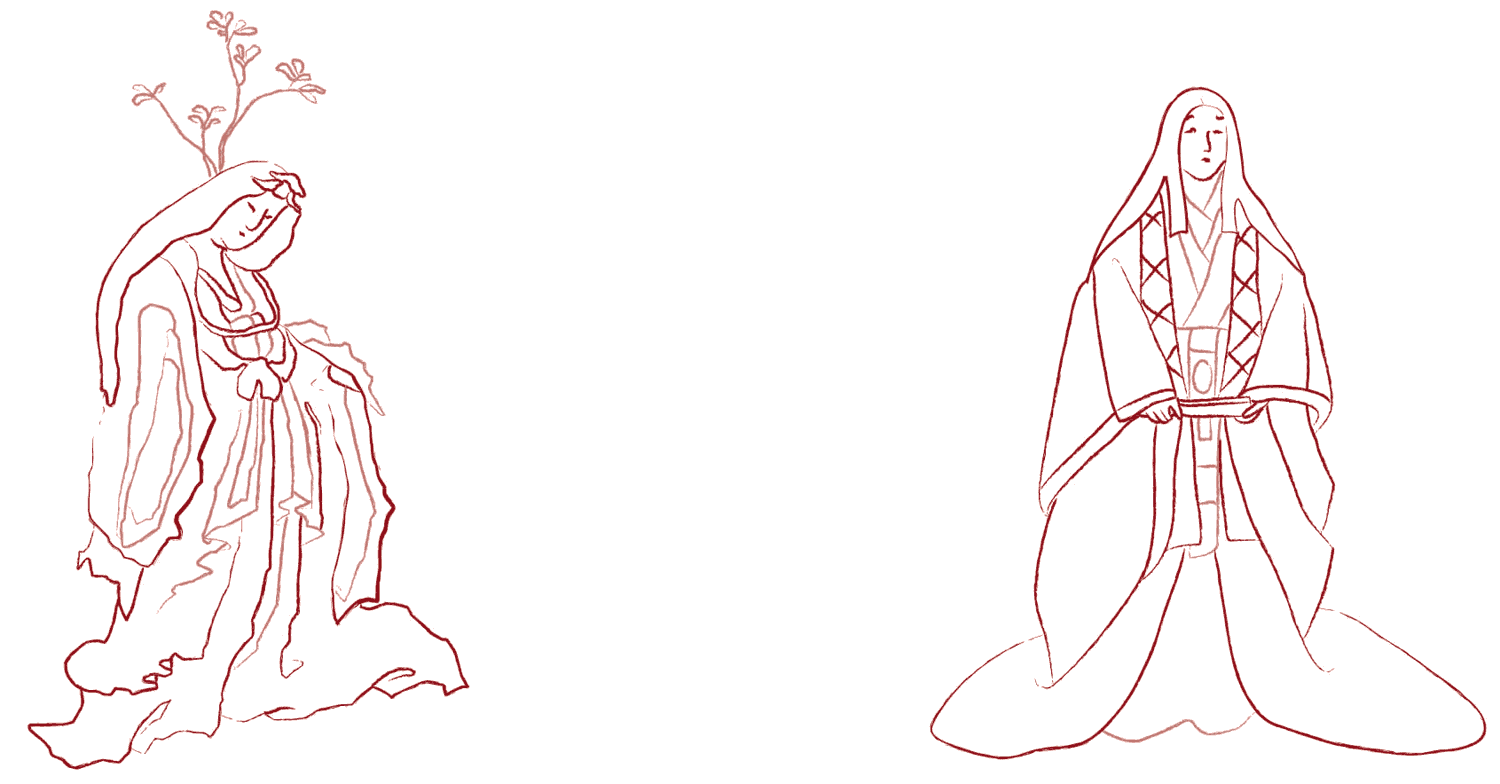

A goddess and a Heian court lady

wearing a many-layered kimono

Japanese Women

Throughout the Ages

EMPRESSES

Seven empresses ruled ancient Japan. Most fascinating was the mysterious, semi-legendary Himiko, credited with unifying the country in the third century a.d. and making contact with China. A shaman who lived in seclusion, by day she was attended by women; by night male slaves gratified her sexual desires, as suggested by director Masahiro Shinoda in a 1974 film.1 Suiko, who ruled jointly with Prince Shotoku Taishi2 from a.d. 592 to 628, was instrumental in bringing literary arts, a legal code, and Buddhism to Japan, and promoted international diplomacy. In a.d. 710, Genmei built Nara, Japan’s first capital city, where four empresses and three emperors held the scepter and civilization prospered until 782.3

HEIAN COURT LADIES

Ladies of the Heian period were judged not just for beauty but also for taste in dress and accomplishments in arts and letters, especially the elegantly brushed calligraphy in which they wrote their renowned poetry. Under their embroidered Chinese jackets, they adorned themselves in multiple robes of exquisite silk, arranged so the up to forty successive layers of beautifully matched colors could be seen and admired at the neck and sleeves.4

.......................................................

A goddess and a Heian court lady

wearing a many-layered kimono

.......................................................

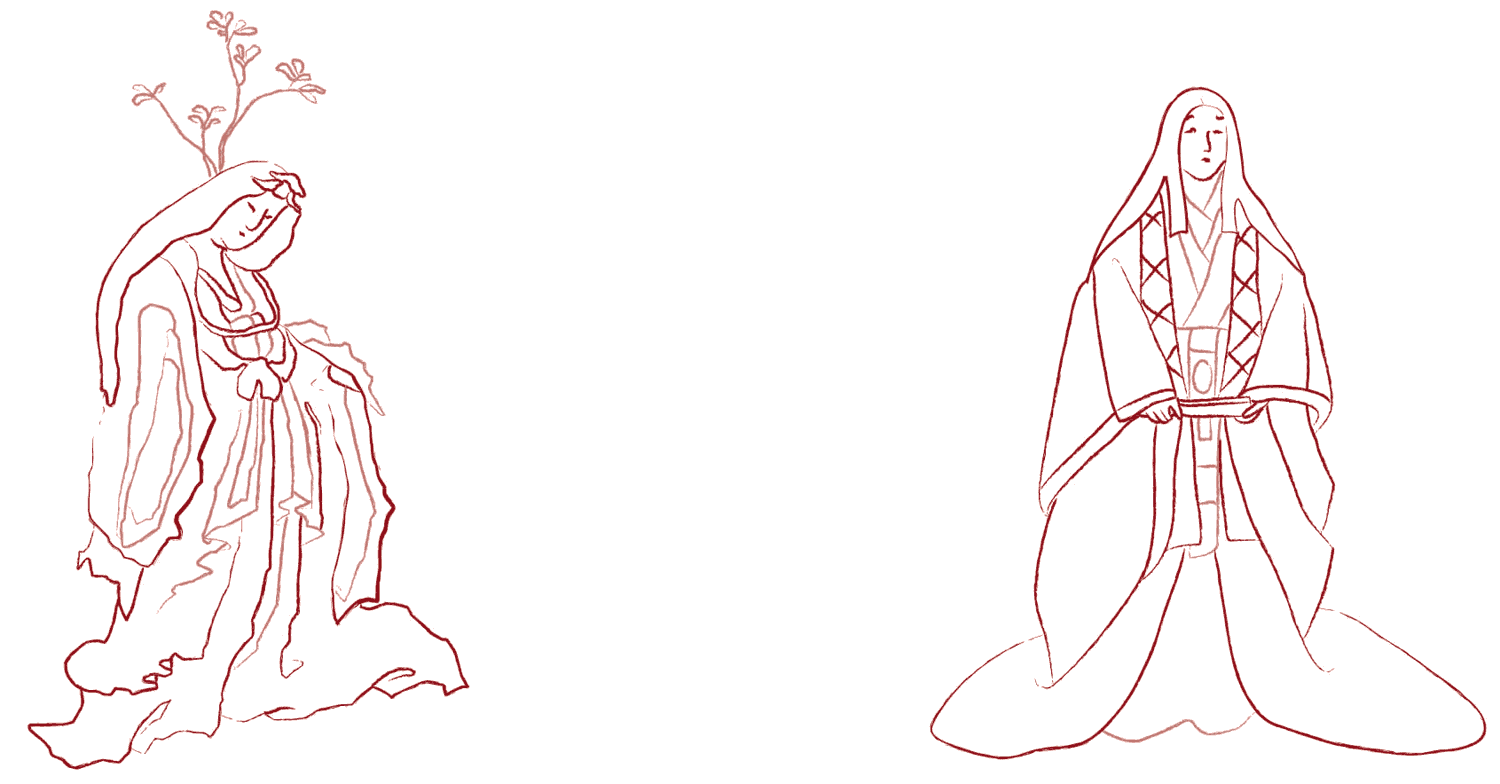

A courtesan dancing, wearing a

kimono with winged sleeves

COURTESANS

Courtesans, part of Japanese society from ancient times, operated actively into the twentieth century. Originally called saburuko, “ones who serve,”9 their titles changed over the eras. They occupied a hierarchy according to the cost of their services, from the lowest ranking hashi, ordinary prostitute, to the elegant, refined tayu of the karyukai, “world of flowers and willows,” as this life was called. Most famously romantic were the tayu of Edo’s licensed district, the Yoshiwara. These women with their seductive wiles were the leaders of fashion, copied by women of all classes as explained by Ejima Kiseki (1667–1736) in Characters of Worldly Young Women (1717): “mother and daughter . . . ape the manners of harlots and courtesans.”10 Prostitution was a widely accepted and very active aspect of society, but certain things set tayu apart as women of the senses, such as their intricate hairstyles and extravagant kimonos tied in front instead of the more traditional back.

Ukiyo means “floating world,” originally a Buddhist term used in the Heian period to describe the sadness and impermanence of life. During the Edo period, when bons vivants of the time sought a word to express their foray into the erotic and seductive world of the senses,a ukiyo acquired a new, trendier meaning by making a pun of the word uki. Meaning both “sorrowful” and “floating,” it came to refer to the transient pleasures of the gay quarters. The word also came to be associated with a certain chic, a savoir-faire in the arts. This included life in the brothels, which had its own set of rules and guides governing the behavior expected of its patrons and denizens.b

A remarkable period of distinctive, highly creative artistic traditions and sexual exploration arose from this fertile environment: the Genroku era (1688–1703), where sex and money ruled.c Sexual pleasure in all forms was an end unto itself, in any and every persuasion, including autoerotica, bisexuality, and homosexuality. In the Yoshiwara, the famous brothel district of Edo (now Tokyo), writers composed lyrical poems and artists made sketches for graphically illustrated “pillow books.” Sex, art, and literature culminated in erotic and exquisite pictures known as shunga, “spring drawings,” which featured prominent displays of both male and female genitalia, an explicit references in satirical masterpieces like Ihara Saikaku’s Koshoku Gonin Onna, “Five Women Who Loved Love” (1686).

Around this time, a mysterious and desirable creature surfaced in this fascinating world of seduction: The geisha, considered the most artistic and accomplished woman in the history of Japan. The term is best understood by the meanings of the two ideograms used to write the word: gei, “art,” and sha, “person.” In the seventeenth century, “geisha” referred to any person engaged in a profession of a three-stringed lute artistic accomplishment.11 Male geisha, who entertained the guests of the courtesans with ribald jokes and antics, were referred to as hokan, jesters.12 Young female entertainers called odoriko, literally meaning “dancing child,” began by likening themselves after male geisha. Performing for high-ranking courtesans,13 they evolved into elegant, stylized ideals of femininity. The geisha was strictly forbidden to compete with the courtesan, but when the days of the Yoshiwara and high courtesans came to an end, the geisha emerged as the premier provider of elegant entertainment in the “world of flowers and willows.”

.......................................................

A geisha playing the shamisen,

a three-stringed lute

HOSTESSES, SOAPLAND GIRLS, AND THE TAKARAZUKA ALL-GIRL REVUE

The days of opulence, grand castles, and sumptuous brothels are gone. But, according to a recent study, ten percent of men in Japan pay for sex at least once a month.14 Women today in the mizushobai, “water trade” or sex business, ply their wares in other ways.

.......................................................

A modern soapland girl,

waiting for a customer