CHAPTER 1

The Wennerberg experience

The issue to be dealt with in this study—giving it its character and content while imposing certain restrictions—is the siting of Michelangelo’s art: how the production of meaning is effected when his art is actively related to its immediate location and to more remote circumstances. Siting Michelangelo is an exercise in positioning his work in illuminating coherences, through the complex act of being on site while at the same time constructing the setting. It means that works of art—as they are sited—are arranged in certain constellations and thus encouraged to perform and surrender new meanings. As each place or site interacts with the sited object (be it an aesthetic theory or a sculpture), it is not only seen from new angles, but engenders qualities previously unknown. There is a productive intersubjectivity to the phenomena of siting, because the object, the site, and the place all impact on one another’s character and appearance; being both a noun and an action, siting can be understood as a matter-of-fact just as much as a continuing work-in-progress.

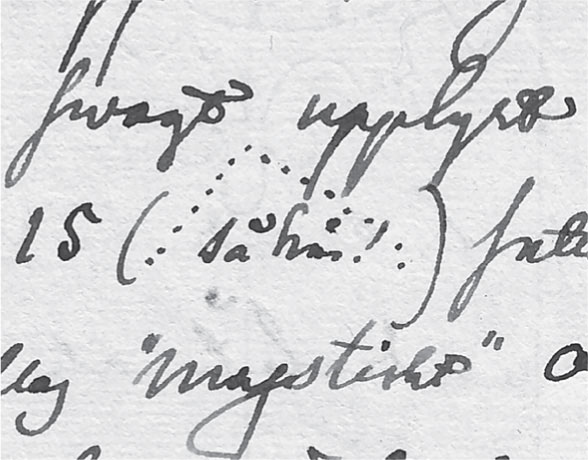

The investigation began when I came upon a long-overlooked poem by the Swedish composer, writer, and politician Gunnar Wennerberg, written in connection with his visit to the Sistine Chapel on the fifth day of Holy Week in 1852. Like several other foreigners in Rome, Wennerberg had come to look at Michelangelo’s paintings and to hear the famous Miserere by Gregorio Allegri.2 Finding a good position close to the chancel screen, he admired the prophets and sibyls of the ceiling, while finding the Last Judgement ‘dark and horrifying’ (Fig. 1.1).3 It was late in the afternoon and the rays of the setting sun barely reached into the upper part of the chapel. The lower part was already darkening and on the altar six wax candles were burning (Fig. 1.2). In front of the wall painting above the altar, fifteen more candles had been arranged in an inverted V, from the upper, central part of the ceiling down to the lower corners (Fig. 1.3).4 At the centre of the chapel the Pope was seated on his throne, his nearest disciples close to him on pews and further below the lesser dignitaries, all of them dressed in elaborate and beautiful garments.

Fig. 1.1 Michelangelo, Last Judgement, 1535–1541. Sistine Chapel, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

Finally, the choir began to sing in a severe, dry monotone, only now and then changing from unison to a simple harmony. When the first psalm had been sung one of the candles was extinguished and there was a silence of a few minutes. The singing started again, with a new text but in the same harsh style, and when the psalm was over another candle was snuffed out. As Wennerberg wrote, ‘So it continued, this strange spiritual exercise, as tiresome for the soul as for the senses, until twenty psalms were sung, and of the candles, twenty-one from the start, only one was left.’5

Fig. 1.2 Michelangelo’s Last Judgement during the celebration of Tenebrae in the Sistine Chapel. (Reconstruction: Petter Lönegård)

Fig. 1.3 Gunnar Wennerberg, Arrangement of Candles in the Sistine Chapel, 1852. Uppsala University Library X 309 c:1, fol. 117. Pen drawing. (Photo: Uppsala University Library)

But if the ear was tortured, he continues, the eyes were not. As the last light abandoned the painted ceiling, cloaking the figures in a threatening darkness, all that could be seen was the Last Judgement and—ultimately—only the figures and objects closest to the altar (Fig. 1.4).

Wennerberg watched the last candle throw its flickering light on the tortured and damned, struggling in vain to reach up towards the disappearing figure of Christ. ‘And it seemed as if these masses were moving in the dusk up and down; Oh, then I was struck by an unspeakable agony, and I turned my gaze from the sight.’6

It was at that moment that a rumbling broke the silence, and Wennerberg looked up to see the Pope, the bishops, and the cardinals all rising from their seats and starting to move towards the altar. They fell down on their knees together and the last candle was taken down from the altar, but not extinguished. ‘A minute of holy silence follows; And, as a cry from deep below, Miserere. Never shall I forget this moment, so captivatingly solemn. I was ecstatic … beyond myself.’7

Gunnar Wennerberg would not have been the man he was, however, if he had not soon recovered from this shattering experience. Born in 1817, he had studied in Uppsala from 1837, received a Ph.D. in 1845, and become a reader in Art History in 1846 on the back of a Hegelian-inspired dissertation, ‘An Effort on the Parallelism between the Development of the Religious Cultures and the Imitative Arts’.8 His 600-page personal diary from Italy is filled with descriptions of the paintings and sculptures he saw, mostly in museums.9 The guidebooks on his tour were Mariano Vasi’s Itinerario (1819) and Franz Kugler’s Handbuch (1837), the latter one of the earliest constructions of a general art history.10

In 1860 Wennerberg was to be appointed by the Swedish king Carl XV to oversee the foundation of the National Museum in Stockholm, and he fought manfully to exclude the Royal Library, the Armouries, and the departments of coins, costumes, and so on from the museum’s galleries and responsibilities alike. He later worked at the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs, was considered for the episcopate, but was instead appointed a county governor in 1875.11 Soon afterwards he was elected to Parliament. In political terms, Wennerberg was a patriotic conservative; on ecclesiastical issues he was more radical. Since his death in 1901, Wennerberg has been most famous in Scandinavia for his student songs, Gluntarna, composed in 1846–1851.

Pondering on his experience in the Sistine Chapel, Wennerberg was troubled, even disappointed with himself. Yes, he admits, he was moved; shaken even. Now, however, the experience has to be viewed in the cold light of reason—and the result would not be favourable. Even if the experience as a whole was stunning, it was of no lasting value, wholly lacking the necessary ‘kernel of its own sound truth’. It was ‘Grand, but without essence, a shallow, seeming life’.12 Deploring the old Catholic Church, Wennerberg found that it still had the capacity to thrill but, alas, not to convince. It spoke to the senses, but not to the intellect. True Christians should light more candles, not sink into darkness, the poet concluded.

As for the art and music that were part of the experience, Wennerberg’s feelings seem to have been divided: ‘Just like many an image, which has its value only at that place where first it was set in the correct light by the master himself—that is, not entirely on its own—so too this Miserere.’13 According to Wennerberg, the melody of Allegri’s Miserere is not particularly beautiful, neither is its harmonization rich nor the rhythm of any particular interest. No, it is the siting that makes the music memorable—and that was to be understood as a weakness. It is like a work of art that has to rely on specific lighting to make an impression on the spectator, he explained. It does not stand on its own, and therefore is not worthy of the hallmark of excellence—a criticism that would no doubt be valid for the Last Judgement as well.

Fig. 1.4 Michelangelo’s Last Judgement during the celebration of Tenebrae in the Sistine Chapel. (Reconstruction: Petter Lönegård)

For Wennerberg, the distinction was not only possible, but even essential. As a Hegelian idealist in the nineteenth century and a promoter of such modern institutions as art museums, concert halls, and art history, he was of the view that works of art had a pure, independent existence of their own. On the other hand, they also had a contingent and less real (or at least less important) substance where they depended on external factors such as lighting, sites, and rites. When evaluating a work of art, it was its former, ideal existence that should be confronted, not the latter. The High Renaissance paintings by Michelangelo on the Sistine Chapel ceiling stood up to this test, while the same artist’s Last Judgement or the musical composition by Allegri did not.

Wennerberg’s account of events in the Sistine Chapel that afternoon cannot be taken as an altogether unfiltered description of what exactly took place, of course. His experiences have been given the form of a long poem, not published until 1881—that is, almost thirty years later, after the dispersion of the Sistine choir following the annexation of Rome by the kingdom of Italy in 1870. Much political and cultural history lay between the event in the chapel in 1852 and the publication of the poem in 1881. It is well known that there was a lively tradition, at least since Goethe’s day, of visiting the Sistine Chapel during Easter and then penning one’s subjective experiences of the ceremony. It was not uncommon, especially among more Romantic writers, to dwell on the ancient customs believed to be still alive in nineteenth-century Rome.14

A description that comes close to Wennerberg’s in its intensity, but that he can hardly have known of, is found in a letter by the painter Ingres from 1806:

Imagine a celestial voice, all alone, as painful as a [glass] harmonica as it slips and passes imperceptibly from one tone to the next. Finally, at nightfall, when the office of plainchant has ended, the Pope descends from his throne; he prostrates himself, and a perfect silence prepares and announces the celestial beginning of those voices that begin the Miserere. Everything, at that moment, is in harmony with this music; it is getting dark, and the twilight scarcely permits one to glimpse the terrifying painting of the Last Judgement, whose prodigious effect impresses a kind of terror on the soul. Finally, finally, I do not know what more to say to you, telling you this overwhelms me, if it can be told at all, for it must be seen and heard to be believed.15

A more likely (and more literary) source for Wennerberg was the novel Corinne au Italie by Madame de Staël from 1807. As a French writer well known in Sweden, not least because of her Swedish marriage, it seems probable that Wennerberg had read her book, if not before then in conjunction with his visit to Italy. The novel is about the poet Corinne and her love affair with the Scottish lord Oswald Neville. Among other incidents, Corinne and Oswald meet after a strong emotional experience in the Sistine Chapel and discuss the importance of sentiment versus reason for religion and belief.16

Besides Vasi’s and Kugler’s guidebooks, it is also possible that Wennerberg knew of Stendhal’s Histoire de la peinture en Italie, published in 1817. Stendhal recommended that one should spend at least a month in Rome, seeing its buildings, sculptures, and frescoes, before daring to enter the Sistine Chapel, otherwise the impression might be too overwhelming.17 While Michelangelo’s paintings are given special sections and the practicalities are addressed—the reader is told how to get tickets to the chapel—there is also a chapter on the ‘Effet du la Sixtine’.18 It gives an emotionally charged account of how the Last Judgement is to be experienced together with Allegri’s Miserere, and it might have encouraged Wennerberg and many others to make the visit.

Several of the observations in Wennerberg’s poem show that he knew the tradition of writing about the Sistine experience, but was still able to give it a personal twist. Few have described like he did the intimate relation between the darkening of the chapel, the ritual, the music, and Michelangelo’s painting. That he was sincerely shaken by the experience is shown from his diary. Usually the notebook was filled with detailed descriptions of artworks that he had seen, together with brief evaluations, but at this point the description becomes talkative and somewhat confused. It ends abruptly with the conclusion that ‘Hedda will have to ask me.’19 Hedda, Countess Hedvig Sofia Cronstedt, was the woman who would become his wife as soon as he returned to Sweden, and evidently the impulse was that this was something he would have to share with her in conversation—it needed a dialogue rather than just being set down in writing. It seems that the poem brought together his visit and his art historical interests and literary influences. Taken together, the poem, the diary, and the other references make it clear that Wennerberg’s writings were not mere literary exercises; they represented a real crisis of his aesthetic consciousness and convictions.

For an art historian today, the effect is almost the complete reverse. Wennerberg’s testimony serves as an encouragement to research the historical sitings of Michelangelo’s art once again; to look more closely at such places as the Sistine Chapel, the Medici Chapel, and the tomb of Pope Julius in order to learn how Renaissance works of art were installed and how they related to their spectators. The keen observations made by Wennerberg on the emotional impact of the Last Judgement in its multimedia context piques our curiosity about what such performances were like in detail, and the possibilities of further reconstruction. In particular it is the relationship between art and music that calls for more thorough research. It is impressive how effortlessly Wennerberg managed to invoke both the bodily senses and the spiritual (or even ideological) issues. The visual arts, the sensual effects, and the politics of the site were all cleverly entwined, and even though less partiality and more transparency of method might be desirable, his all-embracing ambitions are inspiring.

Wennerberg’s attitude goes on to raise historiographical questions about the roots of art history, and how from early on it came to exclude from its discourse such fundamental aspects of art as spectatorship, site specificity, and soundscape. A refusal to listen is still one of the discipline’s most problematic features, after all.

The very concept of siting, finally, inspires methodological and theoretical reflection, fuelling attempts to find new ways of explaining and understanding art. In short, Wennerberg’s poem is a useful prelude to an exploration of the historical, historiographical, and theoretical siting of Michelangelo’s art and artistic convictions.