CHAPTER 2

Practices and theories of siting

Considerable advances have been made in our knowledge of Michelangelo’s art as site specific, and of how individual works—from the Roman Pietà to the frescoes of the Pauline Chapel—speak to spectatorship and siting.20 However, there is still more to be learnt, and much remains to be done in order to integrate this knowledge into an overall understanding of Michelangelo’s artistic enterprise and his artistic credo. The theory also requires attention. It is probably not an accident, then, that Alexander Nagel and Joost Keizer in their recent discussions of the site specificity of Michelangelo’s art seem to arrive at altogether contradictory conclusions. For Nagel, the Medici Chapel was constructed by Michelangelo as a sculptural installation in direct competition with the developments of Renaissance painting, and he finds it comparable with the likes of Dan Flavin’s 1964 Green Gallery show of fluorescent light bulbs.21 Both works place the spectator in the midst of an aesthetic experience. According to Keizer, however, Michelangelo paid little attention to site-specific issues, which was one of the reasons why so many of his sculptures remained unfinished.22 Absorbed by the relationship between himself and his own work, he did not give much thought to its eventual siting or to spectators. The two authors’ definitions of site specificity differ only marginally, Nagel seeing it as something that is ‘embedded in environments’ and Keizer as something that is ‘made with a specific location in mind’.23 The slight difference of perspective is telling, though; the one considers works of art as they appear in a certain context, the other is more concerned with artistic intentions. Before the present study embarks on an analysis of Michelangelo’s art from the perspective of its siting, it thus seems sensible to clarify how the concept itself is best understood.

Douglas Crimp well recalls the shock and bewilderment he felt on encountering Richard Serra’s work Splashing in New York for the first time in December 1968.24 In one of the rooms Serra had thrown about molten lead, letting it solidify where it had accidentally stuck along the edges between the floor and the wall. Among the intriguing components of this work were the difficulties of classification, it being neither painting nor sculpture, and most of all the difficulty or downright impossibility of maintaining the work. It could not be transported anywhere without being destroyed, and thus resisted all commodification, says Crimp. Some years later Serra’s Tilted Arc became a paradigmatic work in the same tradition of site-specific art (Fig. 2.1). Placed in the public square in front of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in 1981, the curved and slightly tilted 3.7 by 37 metre sculpture, made out of solid, weathered steel, was removed within a matter of years in 1989.25 While considered dominating and even threatening by some, the artist himself pleaded for its right to remain at the site it was designed for, and refused to have it erected anywhere else—to remove the work is to destroy the work, was the artist’s argument.26

Fig. 2.1 Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, 1981. Foley Federal Plaza, New York. Corten steel. (Photo: Getty Images)

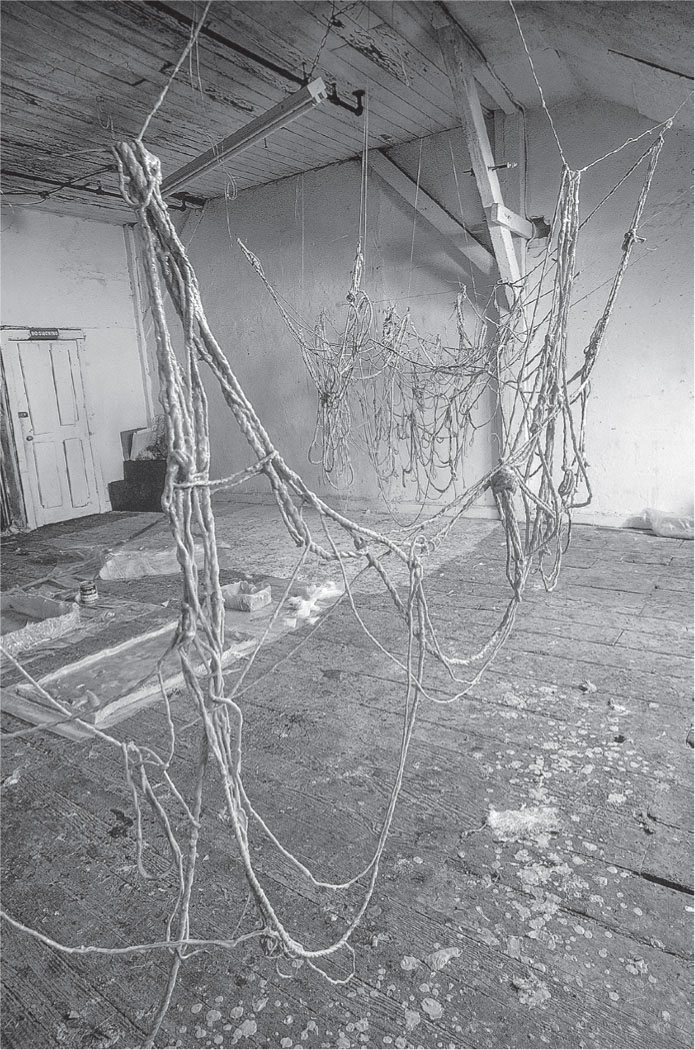

The works of Eva Hesse from the same period and tradition point in a slightly different direction. Her seminal piece Untitled (Rope Piece) from 1970 consists of ropes of different dimensions, dipped in latex and hanging by invisible threads from the ceiling (Fig. 2.2).27 The ropes are all tangled up and snarled in a chaotic fashion, like a three-dimensional, random doodle. This work too is site specific, like Splashing and Tilted Arc, and it ‘cannot be removed without being destroyed’. The difference is that the possibility of change, and even the urge for transience, is embedded in the work; it will not lose its fundamental characteristics and aesthetic expressiveness, almost no matter how it is transported, rehung, or re-sited. Like Serra’s works, it relates physically to the spectator, but with its latex succulence it evokes bodily sensations of a different kind. Without being figurative, it has associations with the agility of the human body, and equally with its capacity for transposition. Hesse’s site specificity alerts the spectator to the contingency of both life and art. It shows that a material firmness is not necessary for site specificity, and that the intense appearance of being sited is more important.

Fig. 2.2 Eva Hesse, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970. Whitney Museum of American Art. Rope, latex, string, wire. (Photo: Getty Images)

Both Serra’s and Hesse’s works are akin to Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, as experienced by Wennerberg. The heaviness and disturbing gravity of the figures, looming threateningly above his head, prefigure the way Tilted Arc was experienced by at least sections of the public. The sheer size of both works adds to the sense of awe. The difficulty of fixing the work or its individual components, the floating and contingent character of Rope Piece, recall Wennerberg’s description of seeing Michelangelo’s fresco in a darkening chapel, with fewer and fewer candles burning. The transience of the experience added to its intensity, to the impression of witnessing something momentary and unique. Most of all, all three cases call attention to the viewer’s sensual experience of the works of art: an increased awareness of both the site and the presence of an embodied self.

One of the first thorough analyses of this kind of art was attempted by Michael Fried in his essay ‘Art and Objecthood’ of 1967.28 His critique was directed first of all against the Minimalist art of Tony Smith, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris, but it also captured the essence of Serra’s and Hesse’s works. For Fried, the most important characteristic of this art was its theatricality. The visual arts, as they give up their uniquely intimate relationship to the public, become theatre, he claimed. This was achieved through the large size of the objects and the holding back of colour, for example. With theatricality came an acute attentiveness on the part of the intended public, the bodily presence of spectators moving about at the site, intent on grasping the artistic presentation. This situation became more important than the production of ideal meaning, and instead of an experienced quality there was the experience of time.

Fried’s criticism is not unlike Wennerberg’s towards Michelangelo: they both want to contemplate works of art undisturbed by all temporary occurrences. Even more so, they would like to have been able to exclude altogether the aspect of spectatorship from their discourses. In this they are in conflict with the present-day humanities, which often stress reception over production. Where attention used to be firmly on the creative act and the biography of the author or artist, the focus is now the public, the reader, or the spectator.29 In this context it may be useful to distinguish between two fundamentally different attitudes towards art: the artistic and the aesthetic.30 The artistic attitude is mostly held by artists, being the point of view that art is something which is created or produced. When the creative act ends, the work is completed. For the spectator, a work of art is not the end of a process but a beginning. It is the starting point of an aesthetic experience. The aim should not be simply to understand the audience and its relation to art, but to understand the work of art itself as an instance not only of the artistic aspects, but also of the aesthetic. Aesthetic objects should not be seen only as extensions of artistic activities, but rather as the result of much broader contexts, and as sited in discourses in which both artist and public are factors to be closely watched.

It is telling that Fried, in his insistence on the theatricality of site- specific art, nevertheless did not mention theatre’s dependence on sound. Theatre is always sound-making, and so is sculpture when it comes to include the acoustic space of the moving, embodied spectator. ‘There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. In fact, try as we may to construct silence, we cannot,’ argued John Cage back in 1955.31 Empirical research shows that it is often through echolocation that humans relate to different ambiences and manage to find their way around them. Not least, the visitor’s own sound-making is important in this context.32

At every place, at every site, there is some kind of soundscape to relate to (defined here as a sonic environment with all its content).33 Soundscapes extend to traditional music, of course, but the concept of music itself is usually understood as referring to self-enclosed, ideal units that exclude the sounds of an audience and other unplanned noises. Given such distinctions, most performed music is better understood as part of a soundscape than as an ideal object. Most music has been created for specified performative occasions, and it gains its meaning from such specific sitings. A soundscape does not necessarily have to include music, though. It can be a prayer, a talk, the ringing of bells, natural sounds—the noise of water, wind, or fire—or simply silence. In the case of the Last Judgement, it is clear that the music sung had a great impact on Wennerberg’s experience of the work. Even without composed music, though, a site such as the Sistine Chapel offers a very specific acoustic experience. Moving about the chapel makes visitors more attentive than usual to the sound of their own bodies and the noises made by other visitors at the site. As in the case of Hesse’s gallery space, it is usually experienced as a very quiet ambience, encouraging a heightened sensitivity and close listening. The public square in front of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in New York also had its specific soundscape, where the urban environment interconnected acoustically with the industrial character of the rusty, leaning arc—echoing the footsteps of approaching pedestrians.

Furthermore, even considered in and of themselves, neither texts nor images are altogether silent: ‘Dwelling in every written text there are voices; within images there are always some suggestion of acoustic space’, as David Toop puts it.34 It is common enough to read images as texts. To view them as soundscapes is more unusual. In the case of the Last Judgement, there are the specific representations of sound and sound-making to be considered—such as the trumpeting angels and the many suffering, moaning figures—but even more abstract representations such as Serra’s and Hesse’s can be read as representing specific sound bodies, to use a concept coined by Steven Connor.35 In the case of Serra, the sound body is dark and compact; with Hesse it is more etheral and organic. Accepting that a depicted body implies a certain sound, just as every sound indicates a certain body, is of the greatest importance for a wider understanding of the visual arts—and not only figurative representations. All those gesturing bodies, all those abstract forms tumbling about, are not simply silent signs, but can be read as sound signals as well.36

A more affirmative appreciation of postmodern art than in Fried’s article, but just as detailed an analysis of site-specific sculpture, was offered by Rosalind Krauss in her essay ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ in 1979.37 Krauss makes a distinction between three different sculptural traditions, loosely defined as the classical, the modern, and the postmodern. In the classical tradition, the art of sculpture was inseparable from ‘the logic of the monument’. By virtue ‘of this logic sculpture is a commemorative representation. It sits in a particular place and speaks in a symbolical tongue about the meaning or use of that place.’38 It is part of the logic of the monument that it is figurative and vertical, which is why the pedestal is such an important part of its structure, mediating between the place to be marked and the representing sign. Against such sculptures, Krauss positions Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell and his Monument to Balzac from the late nineteenth century. With these two projects, the logic of the monument was negated for the first time.39 The statues never became associated with particular sites, but were spread in different versions across various museums, representing ‘a kind of sitelessness, or homelessness, and absolute loss of place’.40 Such is the fate of modernist sculpture, she claims, and it seems almost inevitable that it should finally be extinguished altogether. In the postmodern tradition, instead, the focus is on the site itself. Works such as those by Serra should be seen as ways of marking and manipulating places rather than as sculptures in their own right. The medium is not the important thing here; it is the artistic construction of place that matters. It is crucial for Krauss that site-specific art is an artistic praxis that has forced critics to think in new ways about art—contemporary art as well as historical. Artists’ performative gestures made possible and even necessary a redefinition of what were once thought of as well-established and even universal concepts. The appearance of a new art made critics re-evaluate not only what art is or could be, but fundamental theories and histories of art as well. From this followed a change in the mood of talking and writing about art and artistic practice.

The latter is developed further by Miwon Kwon, first in a 1997 article and then, better illustrated, in book form.41 Kwon recognizes three different layers or phases in the understanding of site specificity. First, the phenomenological layer of Fried and others, who tried to analyse what it is to experience a site-specific work—how it comes to embody the spectators’ presence before the work, choreographing them and adding the aspect of time to their experience of it. A second layer stresses the more institutional aspects, as is singled out by Krauss, for example. Here the concept of art itself is questioned and relativized. Third, there is the discursive phase, where it is asked more explicitly who is in control of the artistic site and what ideologies are at work there. Artist and critic are both now nomads in a capitalist art world, their expertise deriving from the exploitation and manipulation of sites of varying specificity. Nick Kaye argues along similar lines, identifying site-specific practices ‘with a working over of the production, definition and performance of “place”.’42

The idea that there is a political aspect to siting is not too far-fetched. Alain Badiou points to the Paris Commune of 1871 as nothing if not an exemplary site.43 It was a site not so much because it encompassed a specific geographical area, but, more importantly, because it set up a logic of its own that separated it from the bourgeois world beyond. The importance of such a site lies not in the duration or the concrete consequences of its existence. It is the setting up of another, different logical apparatus that is the hallmark of the site; its very different functionality. From Badiou’s example it becomes clear that, for a siting to take place, something more is needed than a particular topography. The site needs to be populated and, furthermore, it needs to be understood for its sensual and ideological qualities just as much as for its natural and material properties.

Recently, Jane Rendell has come up with the concept of site-writing in order to explain not only her field of interest, but as a way of writing about site-specific works of art. It is inspired by Mieke Bal’s concept of art-writing, where the work of art and its siting comes first and theory is asked to simply follow.44 As with Krauss and Kwon, there is an emphasis on the issue of method and style. Site-writing not only aims to uncover ‘the material, emotional, political and conceptual’ aspects of art as ‘remembered, dreamed and imagined by the artist, critic and other viewers’, but to do this in a way that mimics the artistic act of siting itself.45 There are things to be learnt not only about art but also from art, and this is especially true of site-specific art and the process of siting. To site-write is not only to write about sites, but to make writing itself appear as a site. Pace Krauss and her followers, though, it is right to add that site specificity is not necessarily only important to postmodern art. Art historians such as Mieke Bal, David Summers, and Alexander Nagel have convincingly shown that it is an equally useful concept in traditional art; indeed, it is the idea of art as an isolated gallery or museum phenomenon that is the exception, and should be seen as something of a Modernist parenthesis.46 Site specificity is a quality possessed by most historical art, and is worth considerably more attention than has previously been the case in the discipline of art history.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgement can of course be evaluated as an isolated, individual painting, and this has often been successfully undertaken. However, it might be just as interesting to consider the extent to which the artist was aiming for an intervention in the Sistine Chapel, as Giovanni Careri suggests.47 The work then appears as one of the pieces in a montage, rather than something that succeeds or fails in fitting in. Perhaps, Michelangelo did not only attempt to construct a perfect work of art in its own right, but to alter and change the site as a whole. If so, the fresco is site specific and is better considered as sited, as part of the whole, than in isolation. Here in Michelangelo’s art there is a chance to nuance and reconcile Nagel’s and Keizer’s views on site specificity. Neither disinterest nor determination to make his works appear embedded in the given environment seem to be appropriate descriptions. In the case of the Last Judgement, it seems rather as if the artist related very consciously to the given environment, but that he did not do so simply by adapting to it, but rather by entering into a dialogue with it. The Last Judgement draws attention to itself as sited precisely by its insistence on its own uniqueness, much like Serra’s and Hesse’s works. Michelangelo’s awareness of site specificity was of a kind that demanded a precise setting for the work, and could not be conceived solely in the abstract. An important reason why several of Michelangelo’s works were left unfinished was that they never found their precise settings—as was true of some of the half-finished works in the Medici Chapel. They were left unfinished, not because Michelangelo did not care about their precise siting, but because he cared too much and was too detailed about it. The sculptures could be completed only in the instant they were sited, and such opportunities never arose.

The concept of place has been more thoroughly theorized than that of site, especially in the fields of architecture and landscape studies.48 Much of the contemporary discourse is founded on the writings of Martin Heidegger, Julia Kristeva, and Jacques Derrida, the latter having collaborated also with the architect Peter Eisenmann on a proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris.49 Their discussions have deep philosophical roots reaching back to Plato, who theorized the phenomena of place in the Timaeus dialogue. Place is a constant and ever-existing phenomenon, it is argued, that provides space for all being and becoming: ‘We dimly dream and affirm that all that exists should exist in some spot and occupy some place, and that that which is neither on earth nor anywhere in the Heaven is nothing.’50 What is translated as ‘place’ here is the Greek word chora, referring to among other things the polis’s territory outside the city proper. In Plato’s and many of his followers’ vocabulary, the chora represented the vague origins of the thetic, the thetic being what is intellectually articulated through a dogmatic proposition, much like a city becomes sited in the landscape. The chora is also related to Aristotle’s concept of the material cause, or hylé, understood not in a static matter, but in active relation to its artistic or philosophical forms.51

Heidegger spoke of the Stimmung or mood that always precedes, and that everything must be adapted to.52 A famous example from his writings is the Greek temple, summarizing the experience accumulated by dwelling at a specific place. ‘Here, “setting up” no longer means a bare placing … Towering up within itself, the work opens up a world and keeps it abidingly in force.’53 The temple not only represents the Greek idea of nature, religion, society etc., but is a living artefact—a materialized thought—within this tradition. Of greatest importance is the mutual relationship between temple and landscape. If the temple is thought of as sited in the landscape, it might be thought that the landscape is simply a neutral place for the temple’s placing; however, the landscape becomes a site only as the temple is placed there. Until the temple is built, the landscape is only a landscape. There is a coupled relationship, therefore, in that the temple is conceived of in relation to its site, while the landscape becomes a site through the appearance of the shrine.

Perhaps even more relevant in an art historical context is Kristeva’s theory of signification. It too builds on the chora tradition, but is entwined with the dialogism of Michail Bakhtin and the psychology of Freud and Lacan. The thetic drive, the struggle to break loose from patriarchal traditions, is one of the main forces behind every urge to signify, Kristeva argues. On the one hand, every text is founded in the chora—the unspoken conditions behind any articulation. On the other hand, the work of art is always a struggle with the Father and with authority. Artistic creations can be understood as efforts to undo and overwrite such predecessors. Paradoxically, the artistic work is an attempt to start anew and to shake off all patriarchal interferences, just as much as it is an embracing of those confining premises.

The concept of intertextuality was coined in this context, as a way of understanding ‘the passage from one sign system to another’ and the work of art as ‘an intersection of textual surfaces rather than a point (a fixed meaning)’.54 A carnival scene is taken as the key example: through an intertextual redistribution it may become a novel, a musical composition, a drawing, or a film. The purpose of intertextual studies is partly to deconstruct the autonomy of the singular work and the artist as its sole inventor. Poetic language can never be monophonic. Within the intertextual model the work of art no longer involves lines or surfaces, but rather, space and infinity, says Kristeva.55 Unlike Heidegger, she is directly concerned with individual artistic work, and in her model every aesthetic expression comes about as a kind of dramatic siting, rather than as a natural development or effortless continuation. It is a resistance to the chora as a ‘site of chaos’, as she speaks of it in one context.56 The drawback is that Kristeva’s theory suffers from an avant-garde mindset that today seems somewhat dated, and could be problematic in relation to the Renaissance. A sited work aims to alter the place of its siting and to affect its viewers, that much is true; however, this is not only in order to outdo its predecessors, but often to produce a heightened awareness of them—to acknowledge and even to celebrate them.

Derrida, meanwhile, is mostly concerned with Plato’s original use of chora and how it has been understood in our own time, not least by Heidegger. From the Greek, it may be translated as a place, a location, a region, etc., but it is also alluded to in Timaeus as the mother, the nurse, the imprint-bearer, etc.57 Eventually it must be admitted that every interpretation is retrospective, anachronistic, and biased, Derrida argues. Even more problematic is that the essence of chora is its very lack of essence, of being yet undefined. The question is whether it is proper, then, even to give it a name. This vague openness of meaning is central for Derrida and his thinking. Remaining with the dreaminess of the yet to be articulated is what is important in architecture, philosophy—and the visual arts. His sympathy is with the hitherto unspoken, with the making and discovery of places rather than their definite and objective existence as fixed sites.

Not only has the concept of place been far more theorized than site, but in itself it is fundamentally more abstract and complex. The word site is often associated with construction work and architectural projects of all kinds, and it is also used in the everyday idiom of the Internet with its websites. Both of these uses point to the constructivist implications of the concept of site. An architectural site has a strong independence, and consists of building blocks that are easily distinguished from one another, but which are still felt to belong together. Webpages linked together as a website have a more direct relationship than solitary webpages in general. Sites, it could be argued, are strongly conceptualized places with the intense presence of individual entities. Also, the word site, when used metaphorically, indicates a degree of tension between different components, between individuals, texts, or ideas. It seems that the dichotomy of place and site is very much an example of the older and more fundamental dichotomy of the chora and the thetic (and similar to the relationship between city and landscape or Heidegger’s concepts Stimmung and Werk).

The site both adjusts and inflects itself upon the place; it stands out as firm and concrete against the still undefined and more dreamlike character of the place. It is far from univocal, though, but offers the structure of a poetic labyrinth to its visitors. In its clear presence, it retains a mystical character, and it resists the narrative or representational structure of many other art forms. An explicit openness of meaning is true for many site-specific works of art, partly because it is so apparent that they have both a ‘subject-side’ and an ‘object-side’ to them.58 The visitor is only able to fully grasp the subject-side of the individual work of art, the current point of view. Yet, the object-side is sensed as an inevitable presence; one manifested by the appearance of ever-new features that cannot emanate from anything but the site-specific works and the site, abruptly revealing new aspects of its seemingly autonomous existence. Moving about a site is to gradually be choreographed into learning about the site, its special structure, logic, and aesthetic ideology. With every step, new features and new constellations appear. This means also learning about oneself, since spectator and site are at all times plainly interdependent. Even site-specific works of art have to be sited by the beholder in order to be experienced as such. This can be done through a visit to the site, as well as by investigation or in writing.

In the theoretical discussions of both place and site, however enlightening they may be, there has been a deplorable lack of interest in the actual sensory experience of the phenomena. The discourse has been overtly logocentric.59 If, phenomenologically speaking, siting is to let things come together under the eyes of a spectator in order to be recognized as they are—both in themselves and in their specific constellations—a bodily presence is inevitable, and thus the site must be experienced with all the human senses, not only intellectually. This is to admit that an image or map of a site is not the same thing as the experience of it. Such an attitude is more in keeping with Maurice Merleau-Ponty than Heidegger, Kristeva, or Derrida.60 It is to claim that intellectual understanding and bodily experience are not foreign to each other, but intimately related. The visitor literally walks about at the site, experiencing it with her feet, hands and the whole body. The air, the light, the smells, and the sounds are all part of such a bodily, site-specific understanding and experience.61

The most enigmatic aspect of a site-specific work of art is its dual nature, being both in and for itself; being a self-contained work of art and what it is in relation to its ambience. It aspires to be a work in its own right, and one that has been sited, as if by accident, at a certain place, affecting that place and transforming it into a site. At the same time, it is clear that its very existence derives from its siting. It would not be what it is if it were not placed precisely here, at this very special, specific place. This is true of Tilted Arc, of Rope Piece, and of the Last Judgement. There is no way around this chiasm. Site-specific works of art must be considered individuals, as caught up in an existential dilemma of being both in themselves and in the world.62 Ultimately, a site is a conceptualized place with strong internal and external relationships. Site-specific works of art relate actively to the site. Siting, then, is the existence or construction of a site or a site-specific experience—the gradual process from place to site, carried along by both artists and spectators as they get involved.

As a method, siting resists the temptations of grand narrative and all its problematic consequences. Instead, it takes on a topographical attitude, intent on a charting of the relatively restricted field that any site is. As Kristeva has shown, a critical dialogue with tradition comes naturally to such an enterprise, and it too can take the form of siting. In the present study, interpretations are sited in relation to classic texts on Michelangelo’s art by such authors as Heinrich Wölfflin, Sigmund Freud, and Erwin Panofsky. They bring a historiographical perspective to the discussion, and their texts have been targeted because of their outstanding quality and subsequent influence on art history. They do not represent the present state of research, of course, but they do add a wider range of thought and a more vivid dialogue than a collection of purely contemporary voices could.63

In line with its general premises, the structure of the present essay is only loosely chronological. It starts with some of Michelangelo’s earliest works, followed by studies of the most important site-specific installations: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the Medici Chapel, and the tomb of Pope Julius II. Then follow observations on the sited nature of Michelangelo’s art in a more theoretical context, in a direct relationship to the chora and the thetic. Finally, there is a return to the Sistine Chapel, the Last Judgement, and Wennerberg’s comprehension of the painting. The book concludes with a short coda, with brief interpretations of Michelangelo’s later works and a few afterthoughts. The essay form also gives the discussion its somewhat spectral outline— more Gérard Grisey than Claude Debussy.64 The purpose of such a non-linear construction is ultimately, and quite naturally, to uncover new aspects of Michelangelo’s artistic achievement.