CHAPTER 3

Early works

Renaissance art theory was intensly preoccupied with the issue of imitatio, or mimesis.65 All the arts were appreciated in terms of their capacity to counterfeit nature—albeit in an ideal form—and it was thought that artistic skill was primarily learnt by copying old masters. In the early fifteenth century, the artist and writer Cennino Cennini described the painstaking route of the young painter, from grinding colours and making panels to the detailed copying of the authorities’ works, first drawing and finally in egg-and-oil tempera and fresco.66 It was only when more mature that the artist was expected to contribute his own inventiveness, and even then using well-studied models close at hand.67 Even an experimentalist such as Leonardo da Vinci advocated Cennini’s routine, stressing that ‘the artist ought first to exercise his hand by copying drawings from the hand of a good master’.68 The place of the young artist was in the master’s workshop, within a strongly patriarchal structure.

It was only natural that great frustration accompanied such an obsession with the authorities. ‘The dark side of imitation’, as a modern critic calls it, was aemulatio, the desire to outdo and overshadow predecessors.69 This classical concept is in many ways a parallel to the thetic drive of Kristeva’s terminology, and it points to an understanding of creativity as grounded in slow incremental developments rather than in sudden inspiration or improvisation.

As early as the classical authors, the inherent strains in creativity were showing. Cicero said that the concept of aemulatio could be understood in two different ways: as a rightful imitation of virtue, or as the unhappy and unpleasant feeling of envy felt when missing something someone else had got.70 Quintilian was more radical in his approach and asked rhetorically ‘what would have happened in the days when models were not, if men had decided to do and think of nothing that they did not already know’.71 With direct reference to the visual arts, he also wanted to know if our goal should be to ‘follow the example of those painters whose sole aim is to be able to copy pictures by using the ruler and the measuring rod’.72 The answer, of course, was a decisive no, and in an influential and often-quoted passage he stated that ‘the mere follower must always lag behind’.73 The truly successful will be praised for outdoing their predecessors, as well as teaching and influencing their followers. All in all, Quintilian’s argument strongly advocates aemulatio at the expense of the more often recommended imitatio.

The question of aemulatio is frequently also raised in discussions of Plato’s low estimation of artistic imitation. As Pseudo-Longinus wrote:

So many of these qualities would never have flourished among Plato’s philosophical tenets, nor would he have entered so often into the subjects and language of poetry, had he not striven, with heart and soul, to contest the price of Homer, like a young antagonist with one who had already won his spurs, perhaps in too keen emulation, longing as it were to break a lance, and yet always to good purpose; for, as Hesiod says, ‘Good is this strife for mankind. Fair indeed is the crown, and the fight for fame well worth the winning, where even to be worsted by our forerunners is not without glory.’74

‘Such borrowing is no theft’ he commented, and instead it was ‘like the reproduction of good character by sculptures or other works of art’.

Throughout the Renaissance the discussion continued in a similar vein. Petrarch, Poliziano, Erasmus, Calcagnini, Dolet, Florido, Bellay, Sidney, and Jonson all related actively to the concepts of imitatio and aemulatio, both in their theoretical and poetic writings.75 Thus Coelius Calcagnini wrote to Giovanni Baptista Giraldi that the goddess Venus was troubled by her son Cupid never wanting to grow up. She asked Themis for advice, who encouraged her to have another child, so that Cupid would have someone to compete with. Calcagnini drew the conclusion that even the most talented cannot make progress without an antagonist to fire their emulation (aemulationem). It is not only our contemporaries we have to compete with, he added, but also with all those who have lived before us and contributed something of enduring value.76

According to Giorgio Vasari, it was just such a thirst for aemulatio that in the early 1490s saw Michelangelo start as a sculptor in the Medici garden. The garden itself was set up to educate young men, mostly nobles, through the copying of antique and contemporary works. From the descriptions it seems that it served as the edifying site of the day for the artistic elite in Florence, with its important collection of antiques, its competitive atmosphere, and its own ideology and logic.77

One habitué of the garden was the sculptor Pietro Torrigiano, described by Giorgio Vasari, Ascanio Condivi, and Benvenuto Cellini as more than commonly aggressive towards his competitors.78 He was presumably not without artistic talent, but had ‘the air more of a great soldier than a sculptor’.79 At one point he hit Michelangelo so hard in the face that he broke his nose, disfiguring him for life.80 Even before that, Michelangelo had been greatly disturbed by Torrigiano, both by his arrogant attitude and his craftsmanship:

and they, going to the garden, found there that Torrigiano, a young man of the Torrigiani family, was executing in clay some figures in the round that had been given to him by Bertoldo. Michelangelo, seeing this, made some out of emulation, wherefore Lorenzo, seeing his fine spirit, always regarded him with much expectation. And he, thus encouraged, after some days set himself to counterfeit from a piece of marble an antique head of a Faun that was there, old and wrinkled, which had the nose injured and the mouth laughing. Michelangelo, who had never yet touched marble or chisels, succeeded so well in counterfeiting it, that the Magnificent Lorenzo was astonished.81

Even though Lorenzo was impressed by the young Michelangelo’s work (he was then about 15 or 16 years old) he also ventured some crticism, pointing out that old men like the faun seldom had that many teeth left. Michelangelo whipped out his hammer and chisel, knocked out a tooth from the mouth, and presented it again to his patron and master for approval.

In only a few paragraphs, Vasari gives a series of telling anecdotes about the violent and disturbing origin of Michelangelo’s art. Set to copy old masters and antiques, he and other young men were fired with aemulatio, a thetic determination to outdo both their predecessors and their contemporaries. Acts of radical adjustment and even disfiguration were always imminent, both in art and in life. In a very Girardian sense, Torrigiano became the scapegoat of the Medicean artistic community.82 His violent and unacceptable manner, and the conflicts that surrounded him, bound his rivals tighter together and smoothed out their own disputes.

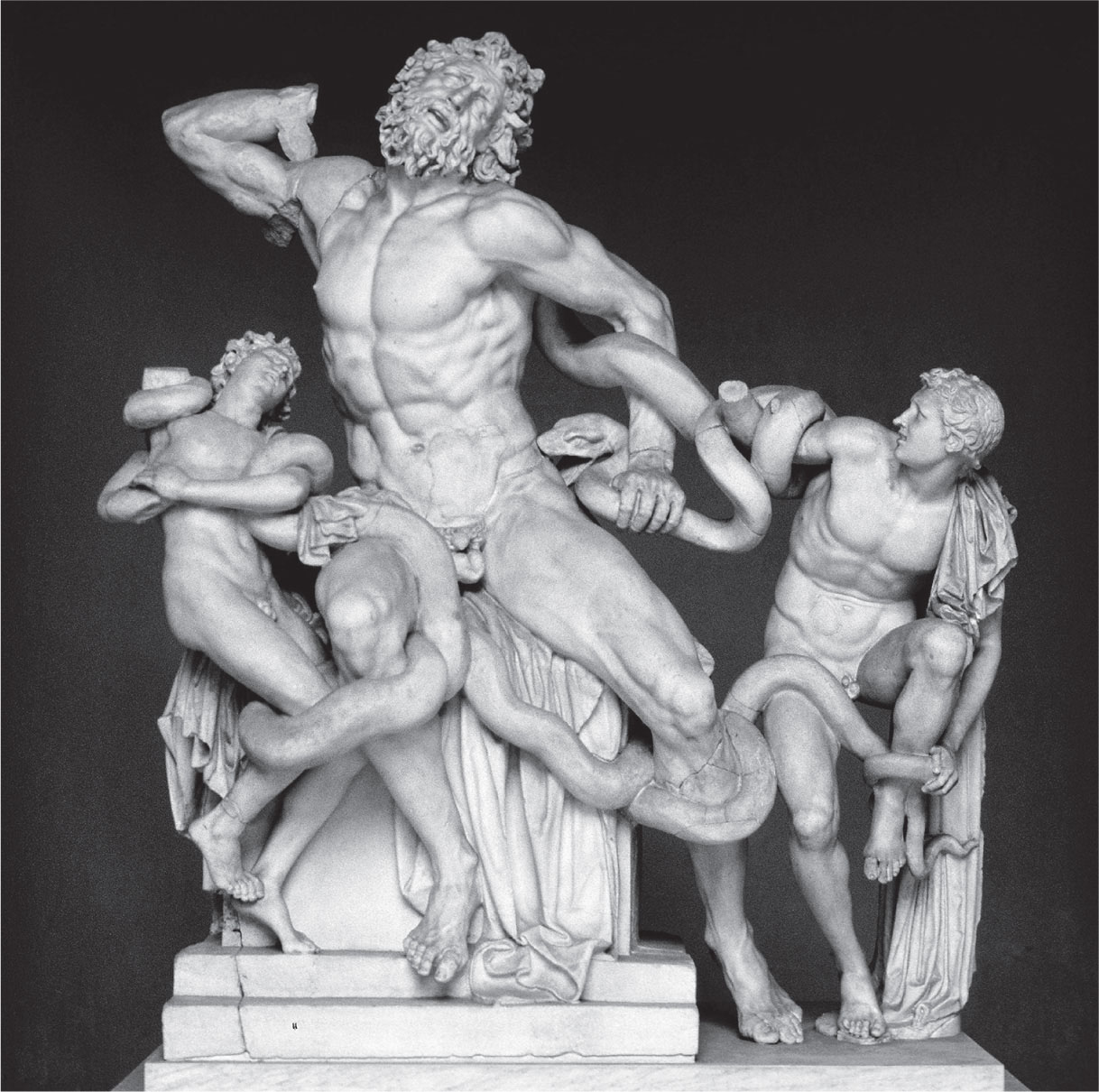

Fig. 3.1 Agesander, Polydoros & Athenodoros, Laocoön Group, Roman copy of Hellenistic original. The Vatican Museums, Rome. Marble. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

Throughout his career Michelangelo remained occupied with imitating and relating to his predecessors, especially the classical sculptors—more so than imitating nature.83 Again and again, he came back to a few carefully chosen works of art, internalizing them in his own oeuvre to the extent that it is often difficult to say if he was paraphrasing the ancients or if he was simply referring to earlier works he himself produced. Already sixteenth-century antiquarians pointed to the Laocoön Group and the Belvedere Torso as particularly important (Fig. 3.1).84 Several of his first works were so close to classical prototypes that they may be—and sometimes were—taken for antiques.

A well documented, though lost, example of this was Sleeping Cupid, created by the artist and sent from Florence to Rome, passing between different dealers and collectors as a classical work until the forgery was revealed. Clearly it was designed to blend in with any collection of antiques. It was reported that Michelangelo took great pride in his skill in copying and artificially aging anything from precious marbles to old master drawings. Among his earliest known drawings are copies of Giotto and Masaccio.85 The skilful Madonna of the Stairs drew heavily on similar works by Donatello. It has even been suggested that the Laocoön Group, sensationally discovered in the early sixteenth century, was nothing but a forgery by Michelangelo himself.86 He had the opportunity, the ability, and the motive, it is argued. Even if the argumentation is problematic, the assumption says something of how close Michelangelo’s art was to the classical masterpieces.

Vasari, who introduced us to Michelangelo’s early feelings of aemulatio, met him in person at a more mature age. Asked what he thought about the practice of imitating classical sculpture, Michelangelo is supposed to have answered with what would have been understood as a clear reference to Quintilian, that those who always trail after others are destined to be left behind.87 Asked about imitatio, Michelangelo’s response was thus clearly a plea for aemulatio. Instead of following after others, great artists interact with them, siting their own work right in the circuit of the very best examples.

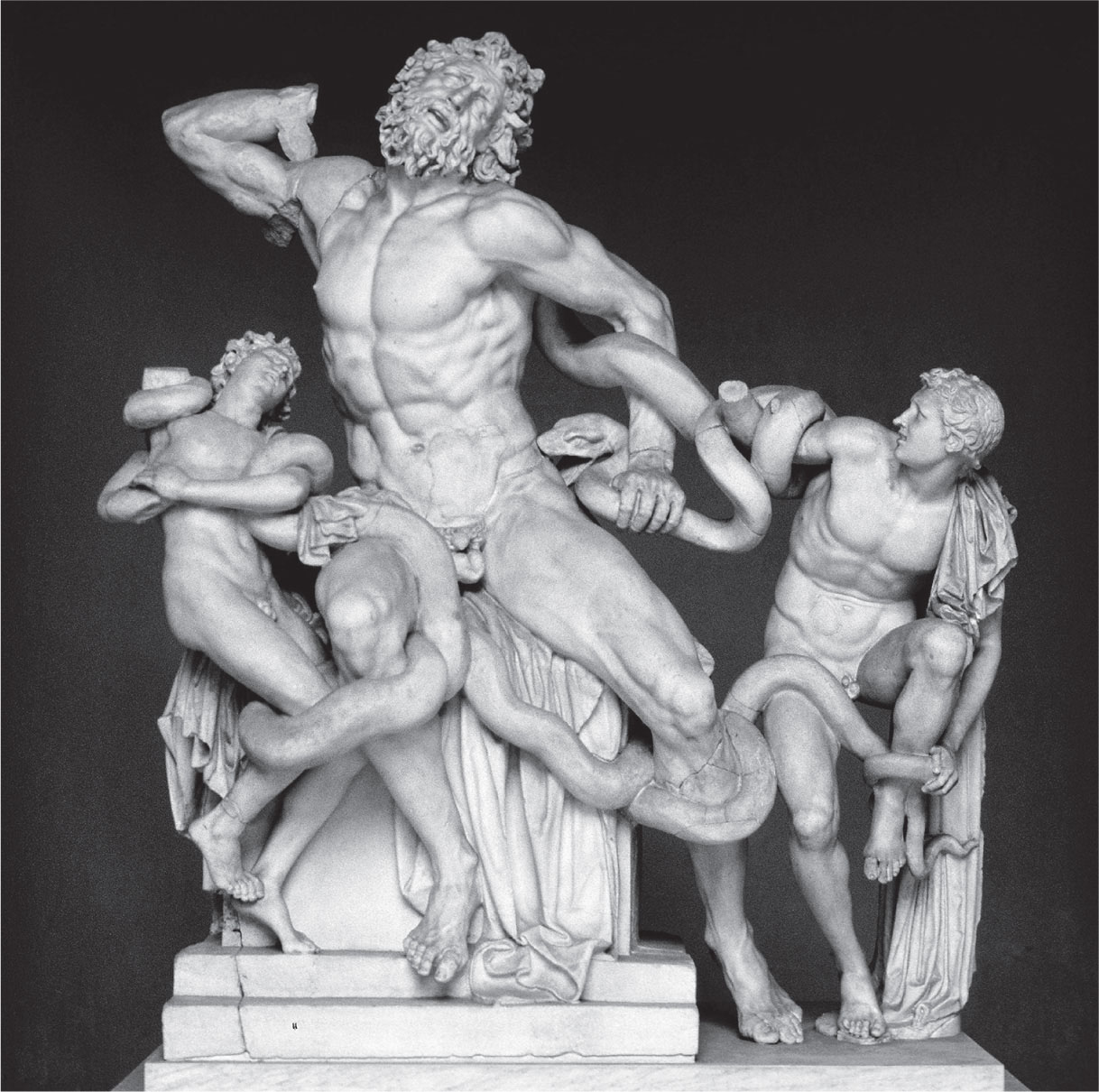

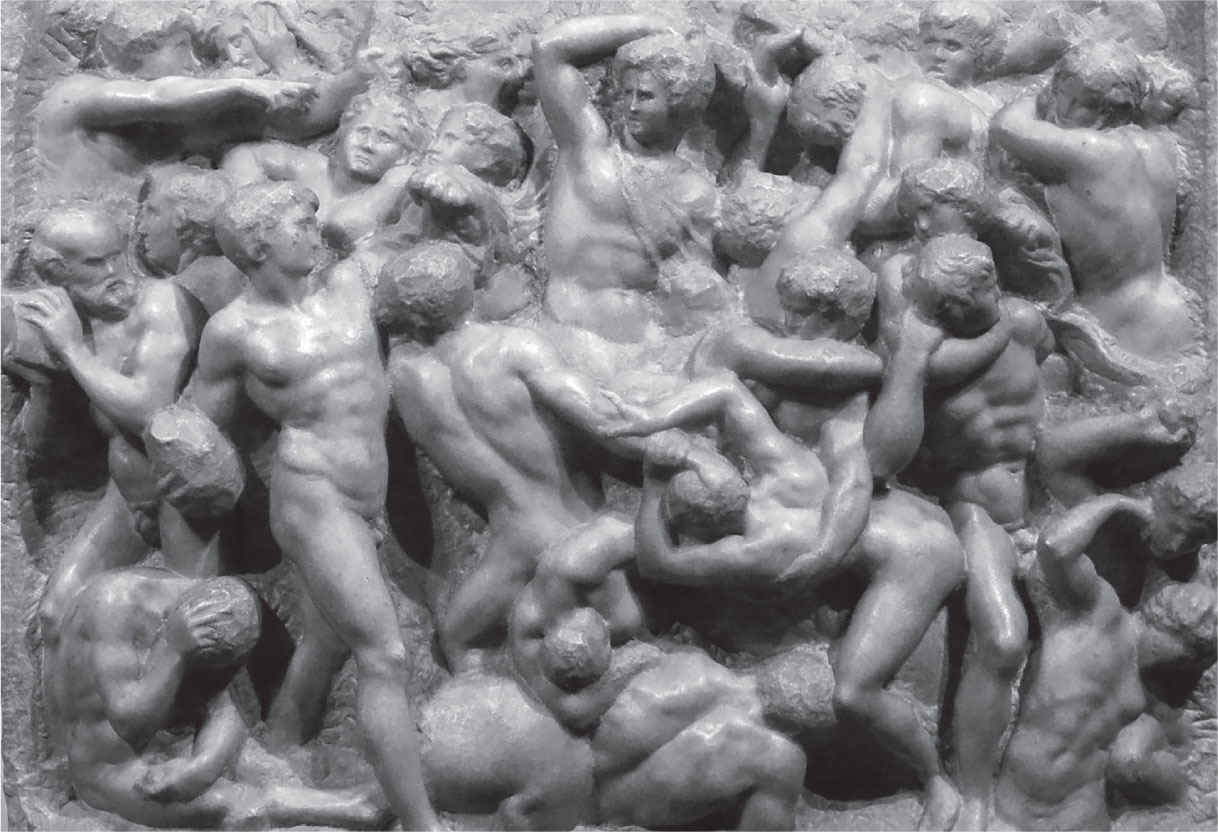

The earliest preserved work by Michelangelo in the classical genre was the Battle of the Centaurs from 1491 or 1492 (Fig. 3.2). The theme was suggested to him by Angelo Poliziano, whose interest in the topic was sincere, being a humanist thinker who claimed that such stories were the instruments of philosophy, and that the philosopher should above all be a philomythos—a lover of fable.88 No antique prototype for the relief is known and may never have existed. To the modern viewer, the scene looks more like a Renaissance fantasy embedded in a classical theme; in its overall ambitions, not unlike Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s famous engraving of nude swordsmen (Fig. 3.3). Michelangelo’s work also represented a violent struggle between a score of naked young men. At the same time, it mimicked Late Roman battle sarcophagi such as the Ludovisi sarcophagus, and it bore more than a passing resemblance to a bronze relief by Michelangelo’s teacher Bertoldo di Giovanni now in the Museo del Bargello (Battle Scene, c.1475). As in Pollaiuolo’s work, however, there is little differentiation between the struggling figures.89 It is impossible to know who is fighting whom in Michelangelo’s relief, or even who is man and who is centaur. The fact that several of the men are fighting one another instead of the centaurs is as evident as it is disturbing; it makes the struggle seem futile and endless, or at best an exercise in misguided playfulness. The scene is set, but no clear narrative direction is given.

Fig. 3.2 Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs , c.1492. Casa Buonarroti, Florence. Marble. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

A few figures stand out: the central figure, who is not really fighting anyone but rather pushing aside and rejecting the figures below him; and a group of three figures in the lower left corner. A young man, seen in full profile, makes a heroic approach towards the central figure. An older man takes cover behind him, carrying a heavy stone as a weapon. According to an intriguing interpretation, the scene represents the triumph of ‘stone over flesh’—both in myth and in art.90 The relief belongs to the garden period of Michelangelo’s life, when such ideas may well have been acute, and the garden itself seems the most plausible setting for this work, both ideologically and topologically. Below the man with the stone, on the ground, sits a figure who is not participating in the struggle. He has lowered his head, resting it in his right hand as if covering his ear to block out the noise of the turmoil—the violent clash of naked, struggling bodies, the moans and cries of the wrestling participants, and the general pandemonium of the scene. The fighters represent the anguish of the reclining figure, just as much as they are the cause of it.

Fig. 3.3 Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Battle of the Nudes, 1465–1475. Engraving. (Photo: British Museum)

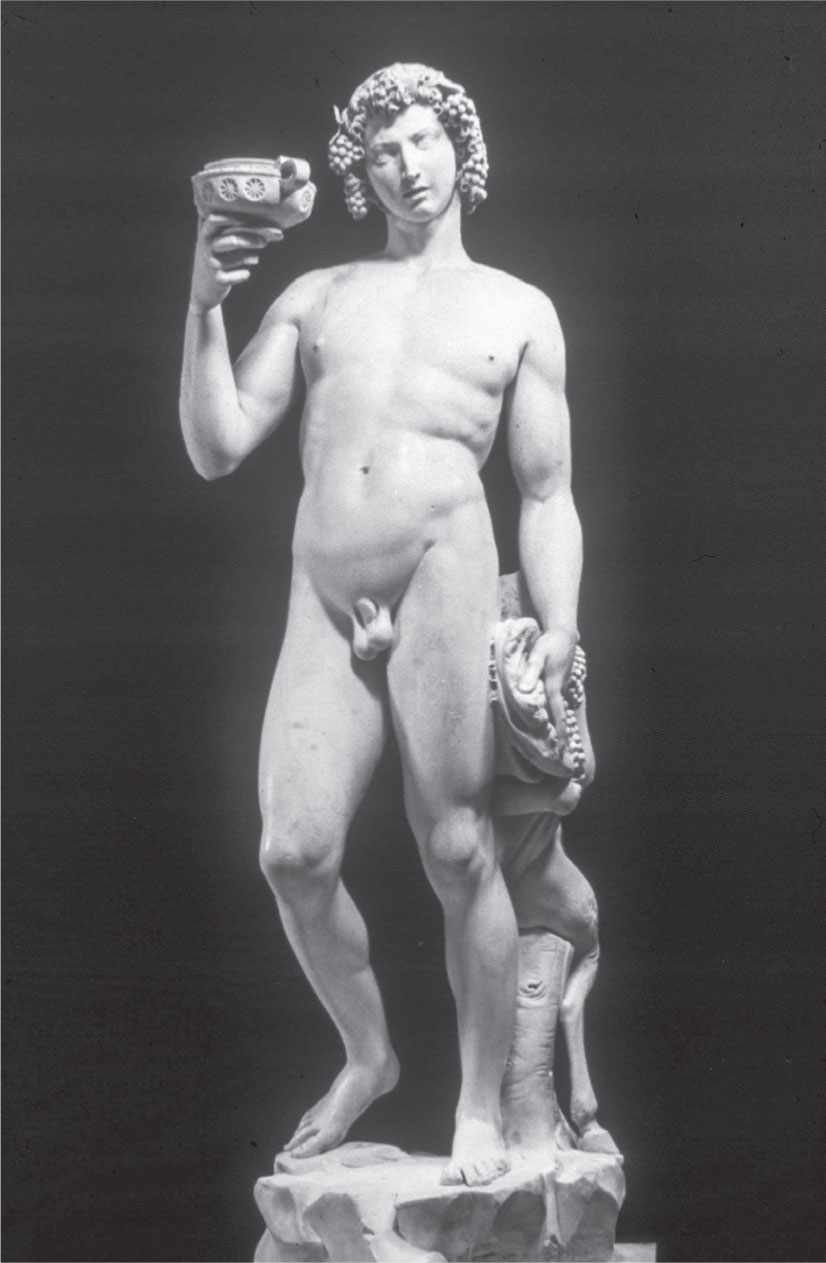

For one of the collectors who had been deceived by the Sleeping Cupid, Michelangelo also produced his first full-size, free-standing marble in the late 1490s, a representation of Bacchus (Fig. 3.4). The god of wine is shown with a goblet in his hand and a small satyr behind his back. In a drawing from the 1530s by Maarten van Heemskerck the statue can be seen in situ, in Jacopo Galli’s sculpture garden in Rome. With its right hand broken off the sculpture looks very much like a classical work, well suited to the garden environment (Fig. 3.5).91 Demanding the spectator’s active movement around it, the sculpture seems consciously intended for an open or even outdoor location.92

As with the battle scene, no antique prototype for Bacchus exists, but Michelangelo’s work may well have been inspired by a lost but well-known work by Praxiteles, who according to Pliny the Elder produced ‘a Dionysus [Bacchus], a figure of Intoxication grouped with an admirable Satyr’.93 A more contemporary influence may have been Marsilio Ficino’s Three Books on Life, written at the Medici court in the 1490s just when Michelangelo was introduced there. The proem of the book introduces the figure of Bacchus as a priest ‘deeply drunken with God’. Like the priest, Bacchus is born twice, ‘once on the vine … when the clusters are ripe beneath Phoebus and born again after the thunderbolt of the vintage as pure wine in its proper vessel.’94 The first birth is natural, as with the grapes eaten by the satyr; the second is cultivated, as with the wine drunk from a fine vessel by Bacchus himself. The sculpture group, with such a reading, represents the refinement of nature into art.

Fig. 3.4 Michelangelo, Bacchus, c.1496–1497. Barghello, Florence. Marble. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

Fig. 3.5 Maarten van Heemskerck, Michelangelo’s Bacchus in the Sculpture Garden of Jacobo Galli, c.1535. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. Pen drawing. (Photo: bpk-Bildagentur)

Classical sculpture and contemporary Neoplatonism are combined here, imparting spiritual content to the former and aesthetic sensuality to the latter. The god is represented with a half-open mouth, as if mumbling to himself or even singing in his cups. The satyr is munching on the grapes, making far louder noises. The spectator’s movements around the group reveal different views, aspects, and meanings of the work. There is an air of talkativeness and festivity about the small ensemble, implying spectatorships of both connoisseurship and revelry. Anyone who took a closer look at the work in the Galli garden must have been bewildered: it was far from evident whether this was a modern or classical work, what it was truly meant to symbolize, and how it had arrived there in the first place.