CHAPTER 4

The Pietà in Rome

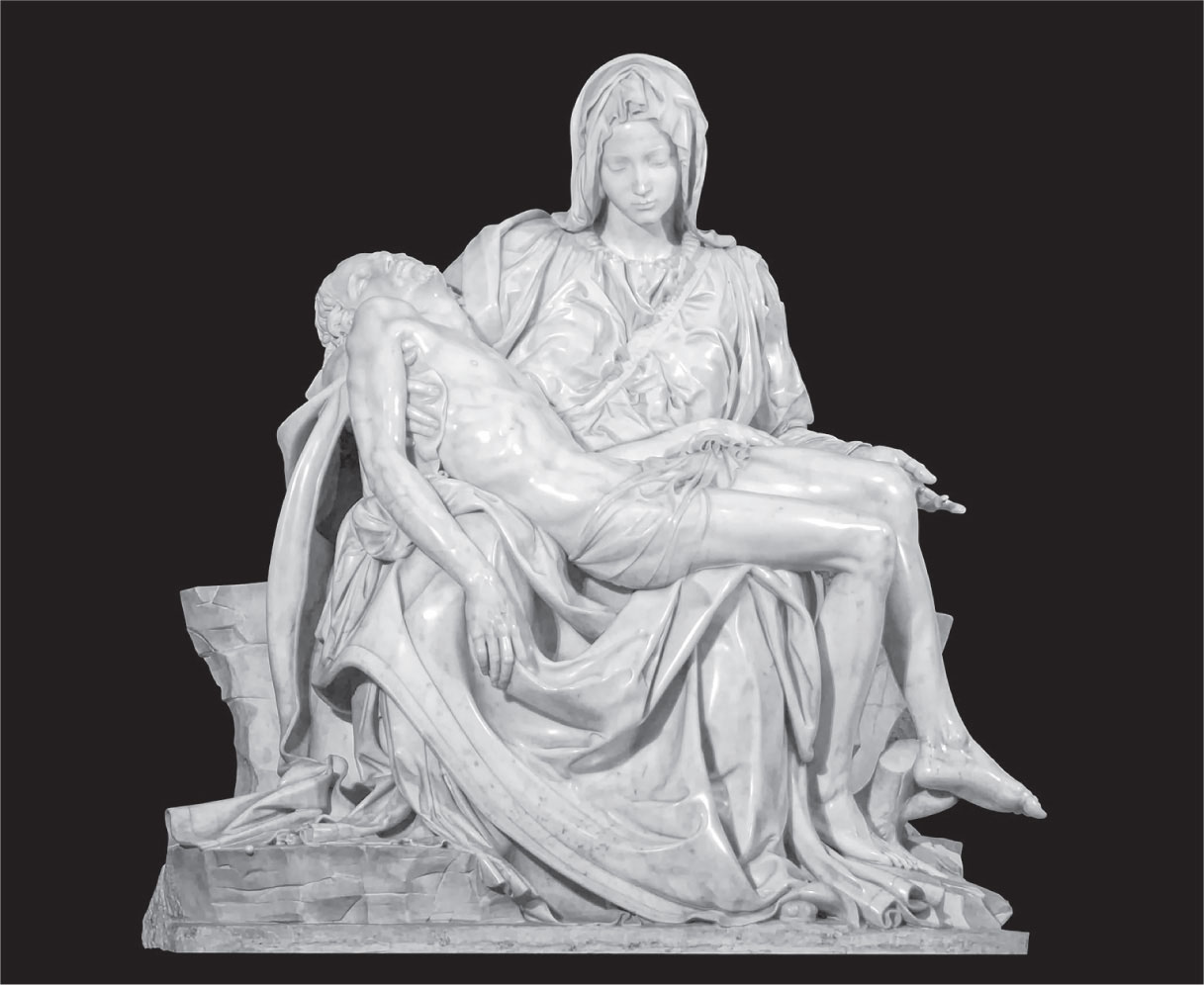

From the first, Michelangelo was engaged in the project of reconciling the artifice of classical sculpture with Christian piety and sentiment.95 An early instance is the marble Pietà in Rome, commissioned by Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas in 1499 to be placed in the French Chapel in Old St Peter’s (Fig. 4.1). In a document concerning the commission, it is described as ‘the draped Virgin Mary with the naked Christ in her arms’.96 This description is telling, for the contrast between the Madonna and Christ is fundamental. Not only because the Madonna is clothed while Christ is not, but because her classical visage, calmness and rhetorical power—as she displays her dead son for all to see—is in stark contrast to Christ’s tortured face and body, his uncontrolled, splayed limbs, his helplessness.

The Madonna’s half-seated position, with outstretched arms and her son deep in her lap, seems to suggest that she is giving birth to him at the very moment of his death. The controlled expression on her face and the lifelessness of Christ’s body make the tightly folded draperies the only part of the composition to manifest unease at the woeful situation.

It has often been pointed out that the motif of the Pietà is unusual in the context of Italian art and it has been assumed that it was his French patron who wished for it, which led the young Michelangelo to conceive of the work based on northern models.97 However, the treatment of the theme is also very close to the design of the Easter Sepulchres of late fifteenth-century Italy, as has been convincingly argued.98 Such sculpture groups were found in great numbers all over Europe during this period, not least in northern Italy.

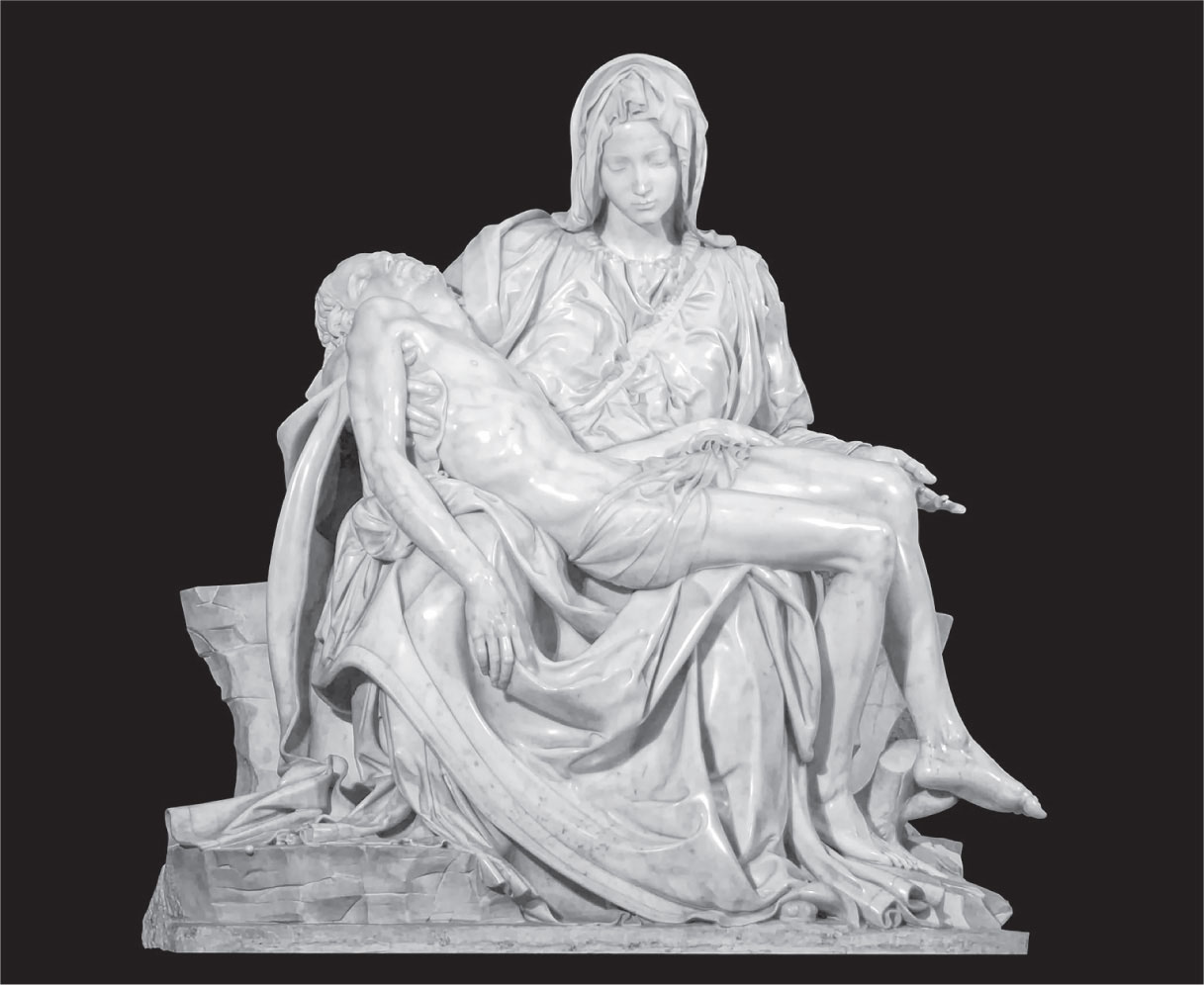

The best-known ensemble is Niccolò dell’Arca’s sculptures in Bologna (dates vary between 1463 and 1490). Several mourning, weeping effigies stand or are half-seated around Christ’s body, which is lying on the ground (Fig. 4.2). They wring their hands and move about as if in violent motion, restlessly circulating around his corpse. Many are crying out loud. This is a despair that cannot stand still or keep silent, finding no repose. One of the Marys is moving so violently that her dress stands out behind her like a sail.

Fig. 4.1 Michelangelo, Pietà, 1497–1500. Saint Peter’s, Rome. Marble. (Photo: Shutterstock)

The group is placed in a small, narrow chapel, similar to a crypt. Today it is normally closed to visitors, but the purpose of the installation was that the spectator should keep company with the mourners in the gloom. Such an experience would be very strong, almost traumatic, for an individual in private or liturgical mourning. Perhaps it might also have had a therapeutic function, offering an outlet for grief and sorrow.

Traditionally, art historians have drawn a hard line between this type of monument and more classic works of art. In his great work on quattrocento sculpture, Charles Seymour explains that:

a double source of style in sculpture was in full evidence as the century came to its chronological close: the sophisticated marble mode of which the [Michelangelo] Pietà is an excellent example, and the counterbalancing, long-lived, motionless art of coloured terracotta, closer as expression to the earth and appealing to literal minds.99

Fig. 4.2 Niccolò dell’Arca, Lamentation of Christ, c.1463–1470. Santa Maria della Vita, Bologna. Terracotta. (Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

According to Giorgio Vasari, however, Michelangelo expressed great admiration for sculptures in the latter mode. Confronted with a work in Bologna by his contemporary Antonio Begarelli, Michelangelo claimed that, ‘if this clay were to become marble, woe to the statuary of the Ancients’.100 Begarelli’s style is epitomized by his Deposition of 1531 in San Francesco in Modena, as in the works of other artists of the Modena School, including his teacher Guido Mazzoni’s The Lamentation from the late 1470s in San Giovanni Battista in the same city.

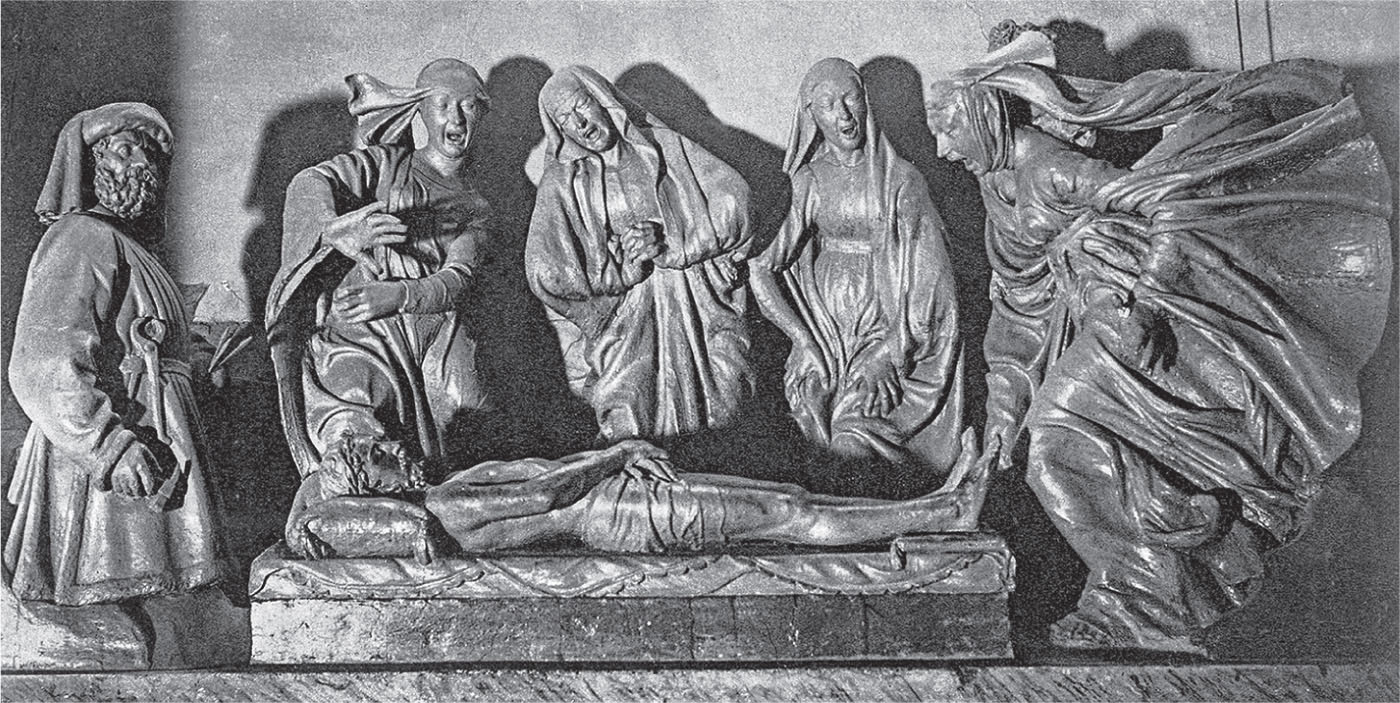

Especially interesting in relation to Michelangelo’s Pietà is Giacomo Cozzarelli’s sculptures for the sacristy of Chiesa dell’Osservanza in Siena, executed in the late 1490s, just before Michelangelo began work (Fig. 4.3).101 It can be assumed that Michelangelo saw and took note of the sculptures in Siena, close at hand in his native Tuscany, especially as they adopted the classical style he preferred. The unusual composition, with its crouching figures crowding round the dead body on the ground, have an affinity with his own Pietà. Compared to Dell’Arca’s sculptures, the facial expressions have been tempered, while the draperies retain some of their expressiveness and the physical handling of the body has become more important. The contrast between the classical features of the women’s faces and Christ’s tortured body brings to mind Michelangelo’s version of the motif, and the relationship between the Madonna and Christ’s corpse is similar in the two works. To sum up, the work of Cozzarelli was much closer in style and content to Michelangelo’s work than northern European Pietàs were, and it seems more reasonable that this was the tradition within which Michelangelo was positioning his work.

Fig. 4.3 Giacomo di Cozzarelli, Lamentation of Christ, 1490s. Chiesa dell’Osservanza, Siena. Terracotta. (Photo: Alinari Archives)

The overall design as well as several expressive details of Michelangelo’s Pietà point to an intended setting for the work. This is in contrast with, say, the Madonna of Bruges, completed a few years later, whose reserved gesture and restrained detailing indicate that the artist knew little or nothing of how it was to be displayed on site. Shortly after the Roman Pietà was completed, however, the chapel in St Peter’s where it had been sited was destroyed. The church was under continuous rebuilding at the time and the sculpture seems to have been transferred from the original site within two decades of completion. It was meant to be placed in the Cardinal’s own chapel, but unfortunately the more precise siting within the chapel is not clear.102

It would be valuable to know at what height the Pietà in Rome was positioned. The base of the sculpture itself is very low, only about 10 centimetres. If it stood directly on the floor beside the Cardinal’s tombstone, spectators would have met the Madonna face to face and— together with her—looked down on the dead Christ. This is also one of the sculpture group’s most striking viste.103 However, it seems likely that the sculpture was positioned either on a plinth or in a niche above an altar.104 The spectator’s gaze would then have been confronted by Christ’s body, looking straight at it, and, by necessity, would have had to look up to see the face of the Virgin.

Every assumption carries with it an amount of speculation, but the design of the sculpture and its implied spectator views, as well as contemporary evidence, suggest that ‘the original installation in Sta. Petronella made the Pietà far more visible in all respects than it is today’, and that one should take account of an ‘extraordinary, heightened sense of intimacy between image and beholder as the Pietà stood on a low altar, rather than on its present high plinth’.105

A well-known incident, reported by Vasari, supports this assumption and indicates that the work was easily accessible not only to the gaze but also to the hand. After the Pietà was completed and placed in the Cappella Petronilla, Michelangelo is said to have overheard two visitors from Lombardy admiring it as a work by ‘il Gobbo nostro da Milano’.106 It is telling that spectators took the sculpture for a work of the more realistic North Italian school, the part of Italy where Easter Sepulchres were commonest. That Michelangelo undertook to stay behind in the church and cut his signature into the marble also suggests that the sculpture was easily reached from the floor. Even if the authenticity of the story may be doubted, its circulation indicates that it seemed plausible for contemporaries that the statue was within his reach from the church floor. And as noted by a recent scholar, the prominent but stylistically causal signature certainly ‘calls attention to the artist’s manual presence’.107

A comparable example in Rome is Jacopo Sansovino’s Madonna del Parto of 1518 in Sant’Augostino, placed in a niche about 80 centimetres above the floor and still today easily accessible for worshippers. Iconographically closer to Michelangelo, though further away in time, is an anonymous Pietà in the church of San Silvestro in Capite. This is a work obviously derived from Michelangelo’s famous version, but probably from the nineteenth century.108 Like its predecessor, it is carved in stone (though not marble), but is also painted in bright colours (Fig. 4.4). Positioned on a bench some 50 centimetres high it is immediately available for worship, and to this day people are often seen and heard praying at its feet, touching the Madonna or Christ with their hands, and bringing flowers or other gifts. Its chapel, which is really just a corridor between the basilica and the street outside, has become a votive shrine containing simple gifts as well as costly donations of silver and gold. Had not Michelangelo’s Pietà become an aesthetic icon back in the sixteenth century, it might well have had a similar history and siting.109 Instead of being enclosed behind a heavy protective glass it might have been within touching distance.

Fig. 4.4 Unknown artist, Pietà, nineteenth century. San Silvestro in Capite, Rome. Painted stone. (Photo: Peter Gillgren)