CHAPTER 5

The Sistine Chapel ceiling

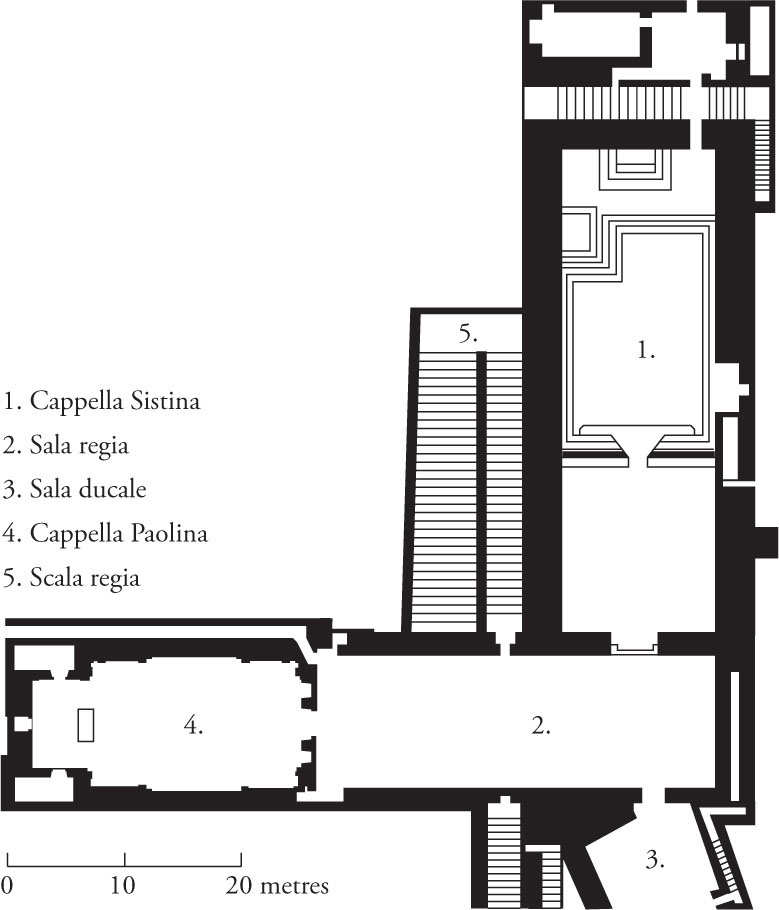

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was painted by Michelangelo between 1508 and 1512 and immediately propelled him to fame (Fig. 5.3). According to Vasari and Condivi, visitors came flocking to see his achievement, to the extent that it interfered with his work. Even before the ceiling was complete, patrons and competing artists at the Papal court were crowding in to get a good look and give their opinions. Condivi wrote that

while he [Michelangelo] was painting, many times Pope Julius wished to go see the work … and as one who was by nature eager and impatient of delays, once half was done, namely from the door to the middle of the vault, he wished it to be revealed, even though it was imperfect and lacked the finishing touches. Michelangelo’s reputation, and the expectation that aroused, drew all of Rome to view it … Afterwards, Raphael, when he saw the new and marvelous style of this work, being a brilliant imitator, sought through Bramante to paint the remainder himself.110

Once completed the ceiling was viewed with great admiration by the Pope, and again ‘all Rome’ crowded to see it. From this it can be learnt that the ceiling was imperfect (imperfetta) when it was first displayed, that everyone had preconceptions about Michelangelo’s art, and that Bramante, Raphael, and others had firm opinions on how the completion of the ceiling should be realized. Vasari tells much the same story, only in even more exalted terms: ‘When the work was thrown open the whole world could be heard running up to see it, and, indeed, it was such as to make everyone astonished and dumb.’111 The Italian original states that ‘questo bastò per fare rimanere le persone trasecolate e mutole’, and trasecolare is more or less the opposite of seculare—to render it non-secular and lift it beyond the limits of history and time.112 The artist appears as a demigod and prime mover, setting the world in motion and making it halt again.

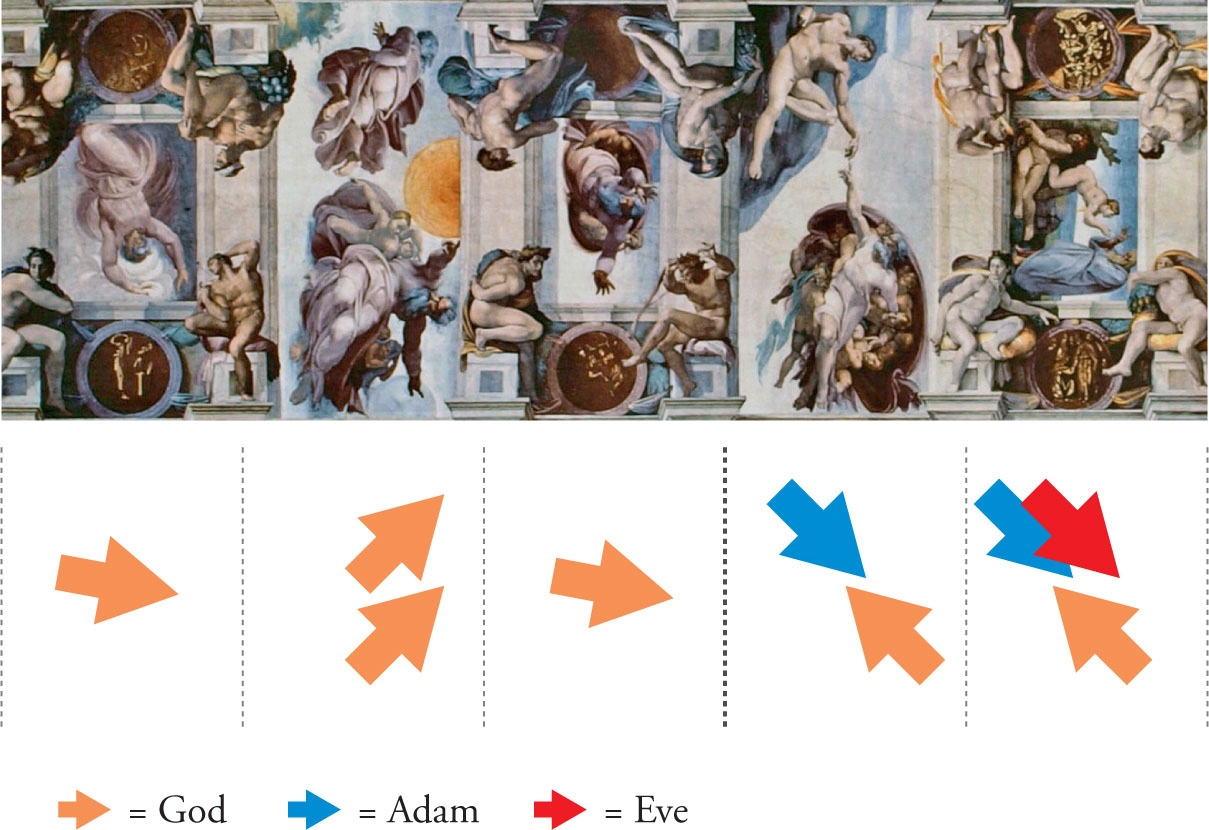

Before Michelangelo, the whole expanse of ceiling (40 by 14 metres) was decorated with stars against a dark blue background, possibly arranged in distinct constellations.113 Michelangelo instead had it divided into several sections, with historical scenes from the first book of the Old Testament: the Creation and the stories of Adam and Eve and of Noah. The first part of the ceiling is given over to God the Father, the second to Adam and Eve, and the third to Noah. The narrative section is surrounded by the twelve prophets and sibyls seated on sculpted thrones with the famous ignudi on top of the intersecting pillars. Below the prophets and sibyls are the quieter scenes with the ancestors of Christ and their families. It is well known that Michelangelo’s composition for the ceiling was not absolutely uniform. The historical scenes close to the entrance side are positively croweded, while the scenes close to the altar contain only a few figures. The prophets and the sibyls by the entrance are smaller than the ones by the altar. The same is true of the ignudi. This was first observed by Heinrich Wölfflin, and was later labelled the ‘Michelangelo crescendo’ by Charles de Tolnay.114

In a concise article from 1890, Heinrich Wölfflin set out to investigate the making of the ceiling, not as a literal but as a visible entity, as he said. It was necessary, as he explained, in order ‘to make the unbelievable understandable’.115 Instead of reading the biblical sequences like a narrative, time spent looking at the ceiling shows that there is a steady enlargement of figures and simplification of the scenes, illustrating the gradual development of the artist’s style over the course of the work. Wölfflin’s hypothesis was that this proved that the work was painted from the entrance door towards the altar, rather than in a narrative order from the Creation to the story of Noah. More important was the methodological issue: looking properly instead of reading images like texts can only bring new and important knowledge about art.

In another study, however, Wölfflin complained loudly about the problems of looking at Michelangelo’s painting:

The spectator may justly complain that the Sistine ceiling is a torture to him, for he is forced, with head bent back, to survey a row of episodes and a great crowd of bodies, all demanding attention and drawing him hither and thither, so that he has no choice but to capitulate to weight of numbers and renounce the exhausting sight.116

Wölfflin then went on to give instructions for the visitor on how to avoid seeing all the chapel’s paintings at the same time:

The quattrocento frescoes should always be looked at first, and only after some study of them should one raise one’s eyes upwards … In any case, it is to be recommended that on first entering the Chapel the visitor should ignore the Last Judgement on the altar wall; that is, he should turn his back on it, for in this work of his old age Michelangelo greatly damaged the effect of his own ceiling by throwing everything out of proportion with this colossal picture which sets a standard of scale that dwarfs even the ceiling.117

Later, discussing the alteration of scale within the ceiling fresco, Wölfflin admitted that the changes are subtle and may be difficult to see at first. Engravings have often concealed the discrepancies, but, as he triumphs, ‘photographs afford convincing proofs’.118 It is true that photographs are good working tools, but their limits should be acknowledged. Above all, they rob works of art of their site specificity. Viewer perspectives and relations to other works of art and architecture as well as to other visitors are all lost. A photographic reproduction robs the work of all context, be it ritual, lighting effects, soundscapes, etc. Wölfflin seemingly did not feel at home down below on the floor of the Sistine Chapel. He preferred to be at his desk with his photographs, and he did not cope well with the distance that was erected between his intellectual enterprise and the experience of the paintings on site.

There have been attempts to account for the Michelangelo crescendo also by scholars of iconology. The best known is Charles de Tolnay’s Neoplatonic explanation in his grand work on the artist.119 There is also an Augustinian interpretation that has received some attention.120 Efforts have been made to identify an author for the programme, and names have been suggested from among the theologians at the Papal court of Julius II, but no documents have been found and no single interpretation has received general recognition.121 The upshot is that Wölfflin’s formalist explanation has retained a firm grip on most scholars. It is not necessary to go into the iconological interpretations in much detail in order to dispute their relevance to the present context. As for the iconography of the ceiling, it poses only minor problems as it can be easily detected in the scenes and figures themselves. In the actual material nothing is said of any crescendo, of course. It is true that a written programme probably existed, and that it had one or perhaps several authors. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that it went beyond literal instructions—a scheme of motifs, perhaps, or the identities of the prophets and the sibyls. It is highly improbable that it said anything about the size or enlargement of figures.

Some have argued that it was after seeing the first half of the ceiling from the floor that Michelangelo altered the format and decided to use fewer but larger figures.122 He must have observed that the figures were a bit small, and that it would do no harm to make them somewhat larger and, in the historical scenes, fewer. However, this theory must be refuted as well. Wölfflin himself remarked that the crescendo is steady from the entrance to the altar. There is no sudden shift and it begins at once (the second figure is larger than the first, and so on). With the historical scenes, yes, the changes are more abrupt, but taken as a whole it is obvious that they are continuous. They start at the very beginning of the work, with the Prophet Zechariah, and do not halt at any point of the working process—until the magnificent figure of Jonah, that is. The precise moment in the painting process when the scaffolding was taken down is still disputed, and it is probably impossible to be certain of what happened at the time. It is definite, though, that the premature exposure of the work was considered an important event in the making of the ceiling by its earliest historians—Vasari, Condivi, and Michelangelo himself.

It is from Condivi and Vasari that we know it was not difficult to obtain access to the Sistine Chapel. The chapel is also mentioned in Francesco Albertini’s early guidebook Opusculum de mirabilibus noue eteteris urbis Rome of 1510, while the edition of 1520 even has a passage on Michelangelo’s paintings:

The upper part of the nave is decorated with the most beautiful images and gold by the glorious [clarum] Michelangelo of Florence; famous [clarissima] artist of sculptures and paintings.123

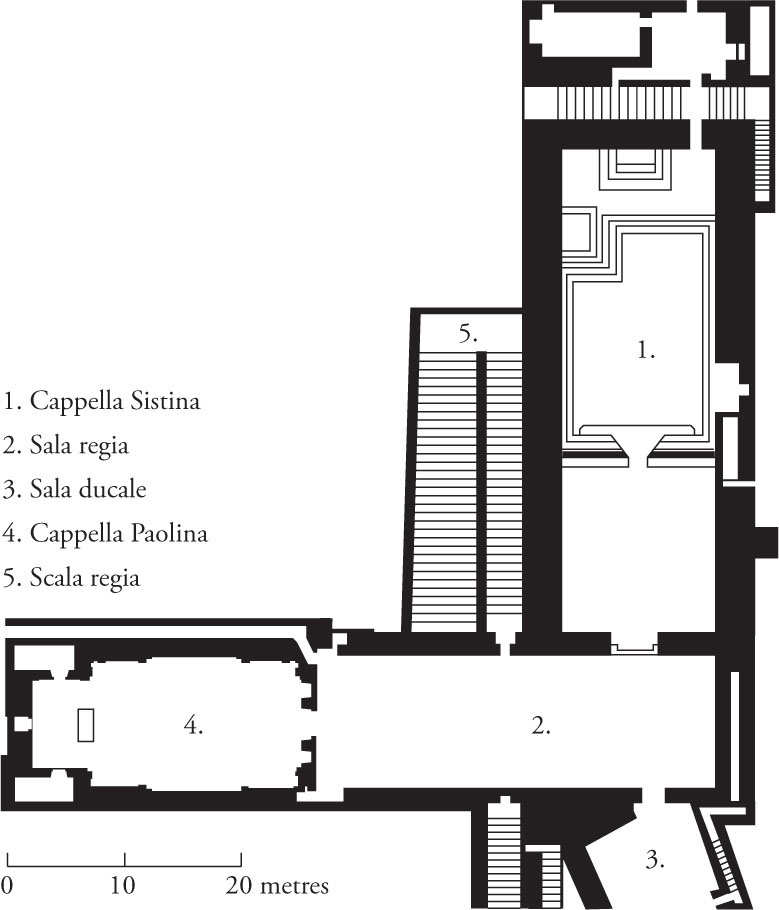

The lines are also quoted in the very popular Roma ricercata nel suo sito, which ran to many editions throughout the seventeenth century.124 It makes particular mention of the beautiful staircase by Bernini that leads up to the Sala Regia, replacing Antonio da Sangallo’s stairs from Michelangelo’s time. One reached the chapel by taking the long staircase to the Sala Regia and entering the chapel from there (Fig. 5.1).125 One might have to tip the Swiss Guards in order to get in, or hire a private guide or use one’s personal contacts, but either way the chapel welcomed visitors. From the first, and despite the air of secrecy, the chapel was in fact a public place and designed for a great number of visitors. It is the Pope’s chapel, but not the Pope in splendid isolation. One was either a visitor or an actor on stage in the chapel, and there was no neutral way of belonging (Fig. 5.2). Participants in the performances at the site were all given their specific architectural definitions, firmly built into the chapel’s structure: the Pope on his throne and the lower dignitaries raised above the floor level, dressed and seated by rank; the members of the choir on their balcony, ready to start singing; the extramurani, the foreign visitors, as defined by the dividing rail. Now as then, standing below and looking up at the splendid ceiling is difficult. It makes it necessary to accept that there is a distance between the viewer and what meets the eye. It means having to cope with the fact that viewing does not take place in the intellect only, but is fundamentally in need of a three-dimensional reality. In viewing, the spectator’s body is choreographed and pushed here and there, as Wölfflin noted, by the preconceived visual structure of both the two- and three-dimensional designs. Such an embodied viewing, furthermore, builds a distance and an acoustic space between the art and the spectator. It also brings the spatial and sensual qualities of the visual arts to the hermeneutical discourse.

Fig. 5.1 Plan of the Papal Chapels. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

Fig. 5.2 Filippo Juvara, Sistine Chapel during Mass, 1711. From Osservazioni per ben regolare il coro de i cantori della Cappella pontificia by Andrea Adami, Rome 1711. Engraving. (Photo: Musikverket)

Wölfflin’s focus on the purely visual was a radical and welcome break with the logocentrism of cultural history and the humanities, which unfortunately pertains to this day. However, with it came an unfortunate break with the other senses and art forms, especially hearing, music, and poetry. It isolated the visual from the site, and the visual representation from its multi-sensorial aspects.

A salient characteristic of the ceiling’s design, besides the famous crescendo, is the numerous enclosed spaces with entrapped figures and the many dense acoustic spaces. The historical scenes are narrowly focused, with little description of the settings. The prophets, sibyls, and ignudi are seated in a way that permits no movement beyond their given siting. The putti serve as caryatides and the monochrome ignudi are close confined, as are the ancestral fathers and families. This is typical not only of Michelangelo’s art but of his poetry too, where there is a remarkable absence of larger units of space or time. Landscape views, pastoral idylls, or sublime panoramas are seldom in evidence, neither are there historical surveys or connected narratives covering longer periods of time; the tendency is rather that time is short and that the scope for anything important to take place is limited. Much of Michelangelo’s poetry has a reflective and rather meditative tone. Where something does occur, however—when tempo and place are connected so that an action can take place—the intensity is instantly heightened.

A recurring motif in his writings is the small, enclosed space of the eye, a metaphor of sight and the visual arts. For Michelangelo, the eye is the whole globe, not primarily its outer membrane or its optics. It is very much a bodily thing. At the end of Poem 21, the eyes become emblems for the brevity of human life, how everything must end with death—‘ogni cosa a morte arriva’. At first the eyes are filled with light, but with time they gape hollow, horrible, and black—‘voti, orrendi e neri.’ The strange, obscure (and uncompleted) Poem 35 is devoted to the eyelid and the eye. Under the eyelid, the eye is always moving. It moves slowly (‘adagio’), only a small part (‘picciola parte’) of the whole globe is visible, and only a fraction of its serene gaze (‘suo vista serena’) is revealed. The conclusion is that he who touches the eye will still not grasp the gaze itself: even when touching the upper or lower parts, one still cannot grasp the yellow, black, or white.126 It is through the eye that impressions pour in and create disorder or strong emotions, a trope that is found also in Cavalcanti and Poliziano, among others.127 There seems to be a special channel connecting the eye and the heart, and in an unfinished madrigal (Poem 8) Michelangelo announces that love throngs in through the eye and forces itself on the heart, where it starts to expand: ‘What is this thing, Love, that enters the heart through the eyes, and in the small space inside it, seems to expand?’128 Poem 38 speaks of the heart as a place for love’s images: ‘Love is a conception born of beauty, imagined or seen within the heart.’129 In a later madrigal (Poem 153) the beloved enters the poet through ‘brevi spazi’, meaning the eyes, so that he has to be pulled apart to be free again. The best-known poem on this theme is Sonnet 166, which during Michelangelo’s lifetime was already considered one of his most important (here as quoted by Benedetto Varchi in his Lezzioni):

My eyes can easily see your beautiful face

wherever it appears, near or far away;

but my feet, lady, are prevented from bearing

my arms or either hand to that same place.

The soul, the intellect complete and sound,

more free and unfettered, can rise through the eyes

up to your lofty beauty; but great ardour

gives no such privilege to the human body,

which, weighed down and mortal, and still lacking wings,

can hardly follow the flight of a little angel;

so sight alone can take pride and pleasure in doing so.

If you have as much power in heaven as here among us,

make my whole body nothing but an eye:

let there be no part of me that cannot enjoy you.130

The poem is as original as it is typical of Michelangelo.131 The somewhat awkward flow gives a mannerist or perhaps unschooled impression, as in the opening lines: ‘Ben posson gli occhi mie presso e lontano, veder dov’apparisce il tuo bel volto’. The theme of the poem is also characteristic. The eye that is raised heavenwards and refines the soul is a typical Neoplatonic figure, found for example in Ficino.132 Yet, coupled with the wish to transform the whole body into an eye, embodying the spiritual so to speak, the classical metaphor is given a non-classical twist. Man should not only rise to the divine, but God should descend to the human as well. The modification of the theme might be accounted for by the fact that Michelangelo wrote the poem for his friend Vittoria Colonna, but it seems consistent with his work and probably reflects his own worldview. It verges on the burlesque: the third and fourth lines, with their detailed rendering of separate body parts (feet, arms, and both hands), but above all in the concluding image of the body longing to be ‘nothing but an eye’. The eye and the body become one here: the ideal is embodied and the body is spiritualized.

Fig. 5.3 Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel ceiling, 1508–1512. Sistine Chapel, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Vatican Museums)

Another frequently visited site in Michelangelo’s poetry is the heart. The eye and the heart are often counterposed, of course; an idea which is repeated in Sonnet 42, a dialogue between the Poet and Love. The former asks if the eye actually sees the beauty it longs for, or if it has its origin within the self. Love answers that beauty truly originates in the beloved, but that it grows in fertile locations, ‘when it runs to the heart through the mortal eye’.133 Sonnet 276 begins with a similar observation: ‘Passing through the eyes to the heart in a moment, so every object of beauty.’134 In one quatrain (Poem 49) he claimed that no face among us can compete with the image of the heart—‘l’immagine del cor’. The most dramatic instance of this trope is found in his long, unfinished love poem (Poem 54) where the loved one, once again, enters through the eyes and is likened to an unripe fruit pressed into a bottle. Once inside, it expands and grows so that it will never come out, and will always remain confined.

In the Sistine Chapel, the same fondness for small, condensed spaces can be recognized; not the globe of the eye or the compass of the heart, but the narrow architectural spaces of self-produced noises and abrupt echoes. They call to mind the early Battle of the Centaurs (Fig. 3.2), but the figures are now all alone in their struggles. Like fruit growing in bottles, the bodies find themselves unbearably trapped and enclosed, while spectators are confronted with a disturbingly rich palette of scattered sounds and noises. God the Father creating the Earth is a rumbling force of nature, producing the sounds of wind, water, and crops. With Adam and Eve, the sounds of sleeping, pleading, and crying come into the world, as well as the crackle of fire. The Deluge echoes the sounds of Creation, but now experienced as a human disaster, with menacing wind and heavy rains. The ignudi, natural as well as the monochrome ones, writhe in elegant restlessness or kick heavily against the strongly built walls to break out of their cramped prison cells (Fig. 5.4). The prophets and sibyls are set in library soundscapes, with the grand figures sometimes sighing, murmuring, and reading quietly to themselves, turning the pages and returning the tomes to the shelves and tables. The composition of the spandrels is more complex and far noisier, with the Slaying of Goliath, Judith and Holofernes, Death of Haman, and Moses Raising the Bronze Serpent to protect his feasting and bawling people. Most violent are the small bronze-coloured medallions with crowded scenes representing the Destruction of the Idol of Baal, Death of Absalom, Sacrifice of Isaac, Death of Joram, and so on. Finally, there are Christ’s ancestors, quietly going about their daily lives: spinning and sewing, combing their hair, reading and writing, nursing and playing with their children, or simply waiting and resting.135 All of these figured bodies and their activities make noises. They may often be taken for granted, but the sounds are always there and without them it would all seem mere artifice.

Fig. 5.4 Michelangelo, Detail from the Sistine Chapel ceiling with the monochrome ignudi of the spandrels, 1508–1512. Sistine Chapel, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

The paintings of the Sistine Chapel ceiling strike a fine balance with the deliberate composition of their sound-making. The Creation lies as a heavy drone under it all, the breath of the winds reaching over the full extent of the chapel. Individual figures are given different voices, deep, shrill, or silent. Every scene is like a different instrument in an orchestra, the disparate figures bound together, even where there is no physical, historical, or visual contact, and despite the autonomy of different scenes and figures. The spectator on site is at the heart of the acoustic landscape, the one who hears it all. If, like many Renaissance writers liked to do, the painting is compared to a window through which another world is to be seen, the acoustic references throw wide the representational windows and allow for a more direct, sensual interconnection between work and viewer. This is an effect that cannot be achieved by looking at photographs or reproductions; it demands a physical presence at the site—however problematic and uncomfortable.

Fig. 5.5 Michelangelo, Detail from the Sistine Chapel ceiling with the Creation of Adam, 1508–1512. Sistine Chapel, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

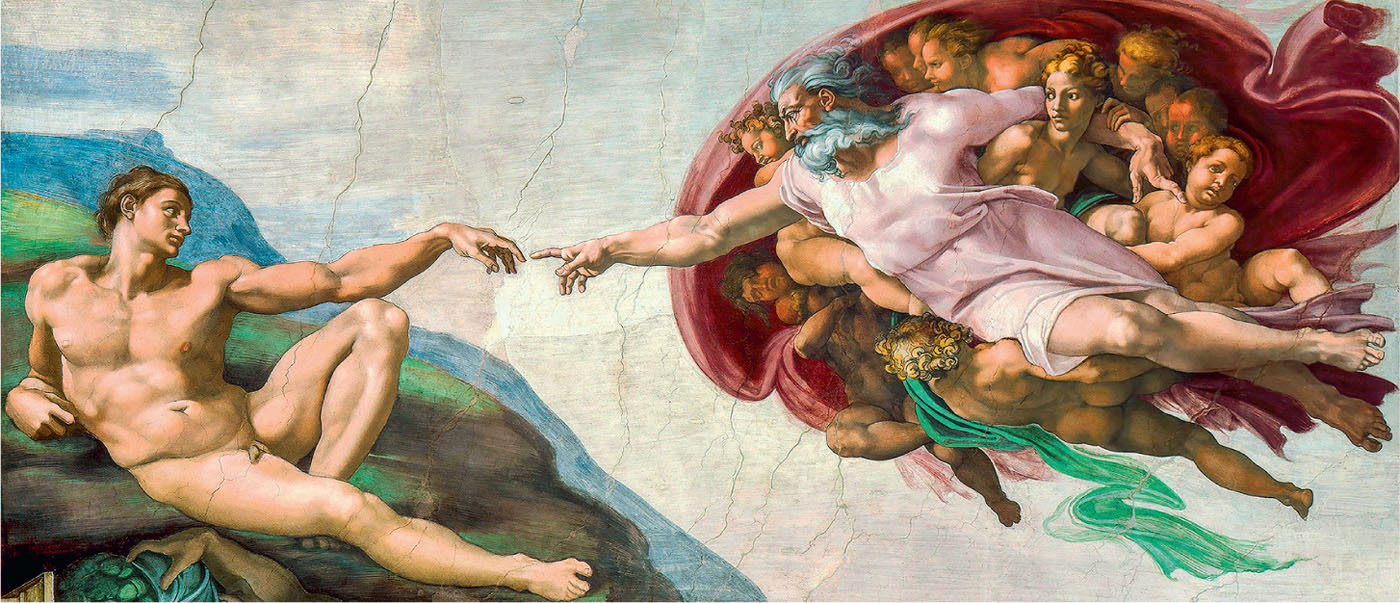

It is only by standing at the entrance to the Sistine Chapel, facing the altar and lifting one’s eyes to the ceiling, that one can see the historical scenes the right way up, the prophets, the sibyls, the ignudi and so on, all at the same time. The gaze is drawn to the Creation of Adam, or, more precisely, to the moment when the hands of God and Adam meet, where Creator and created are connected. This is the scene with the sharpest silhouettes, the strongest spatiality, and the most articulated perspective within the ceiling; this is emblematic of the point where humankind as well as God came into existence (Fig. 5.5).

Michelangelo has not placed these scenes strictly in accordance with the narrative order of the first book of Genesis. In the first scene, God separates Darkness from Light, tenebrae a luce, before creating the Sky and the Earth, caelum et terram, and only in the third scene is God hovering over the waters as if admiring his work and ‘seeing that it is good’. With the making of Adam, the text is followed more closely: ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness’.136 The plural form (faciamus) should be noted, as well as the figures accompanying God in the previous ceiling scenes. It seems that God needed mankind to become Himself. Before the Creation of Man, God was not One but still the Many, accompanied by other divine beings. Only when Adam and Eve were created, as representations of God himself on Earth, did God become One, from now on to be adored and worshipped by mankind. Clearly, this was a turning point in the biblical Genesis as well as in the ceiling fresco.137 The mirroring effect is enhanced by a break with the continuity of the compositional outline (Fig. 5.6). Since the first part of the ceiling belongs to God the Father, it would have been natural to position God next to the other Creation scenes and Adam next to the image of Eve. Instead, God seems to be travelling from the Eve scene back to Adam, while the reclining Adam is positioned on the ground and next to God’s part of the ceiling. The chronology is inverted, as if Adam existed already before God came about to create him. Before the making of Adam, God was a natural force, outside time and existence. With the making of Adam, representation comes into play. In the scene where Eve is created, God for the first time is placed at ground level, allowing Eve to adore and worship him. His existence is placed within a human context; he stands on his feet instead of hovering in the air, and he has moved into the world that he has created. Comparing his appearance in the earlier and later scenes, it is clear that God is tempered and rendered more human-like by acting on his wish to create mankind. He has become sited, relating to the features of his own Creation and its new logic. Without the Earth, without Adam and Eve, he would be someone—or something—else.

Fig. 5.6 Direction of figures in the first part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

Man is tempered as well. According to Marsilio Ficino, the first man was utterly beautiful because he was still unaffected by any use of his senses.138 After the Fall, however, the senses became separated into sight, hearing, taste, and so on, and confusion arose. There was no perfect order and it became difficult even ‘to listen to the lyre and enjoy the meal at the same time’.139 In the scene where Eve is created, Adam already looks more domesticated and weary. In the ceiling’s last scene, Noah is a figuration of Adam, but now he is mankind as old, drunk, and despicable. Many of the ceiling’s other figures can be read as variations on the same theme, struggling with the human condition. Not least it is Christ’s ancestors who display their tired and melancholy existence.

In Renaissance art theory, in Vasari for example, the Creation of Adam was often referred to as the origin of art.140 God was the first artist, giving ideal shape to what was interpreted as the first sculpture: Adam. Michelangelo places the spectator on the chapel floor in direct relation to this central scene, and thus reinforces the mutual dependence between the spectator and the ideal, between what is down below and what is to be seen on high. In all its glory, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is a messy thing. In what otherwise might have been taken as the required pure, abstract, and silent viewing of the ceiling, it manifests the presence of an implied spectatorship from the chapel floor that is corporeal, spatial, and pregnant with sensual experience.