CHAPTER 6

Portraits of the artist

Michelangelo by and large avoided the art of portraiture, and he never painted any actual portraits, although he produced a few drawings and sculptures said to represent certain individuals.141 Had it been left to him, Renaissance art might have been lacking one of its most successful and characteristic innovations. It is appropriate, therefore, that he never painted a true self-portrait, and that the most important image of him was painted by his greatest rival, Raphael, in a representation that cannot be considered a portrait proper without serious reservations.

The story goes that in 1510, just as Raphael was about to complete The School of Athens, he was given a preview of the half-finished ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel.142 Astonished by what he saw, he added a foreground figure to his own work, an image of Heraclitus that shows a distinct resemblance to Michelangelo—a figure that is missing from the large cartoon of his work now in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan. Not only is it very close to other known portraits of him, it is also altogether Michelangelesque in style (Fig. 6.1).143 At the centre of Raphael’s composition are Plato and Aristotle. The former is pointing at the sky and the divine ideas above, while the latter makes a tempering gesture with his right hand, indicating the earthly things that demand our more immediate attention. It is a unique feature that there are not one but two protagonists in this work, the scholarly dialogue itself— rather than any other specific idea—being the heart of the matter.

The other philosophers are also represented as involved in intense debates, arguing and disputing over conflicting ideas and opinions. Vasari was among the first to point out that the work included disguised portraits of some of Raphael’s contemporaries: Leonardo da Vinci, Donato Bramante, and the artist himself in a black cap at the extreme right of the composition (Fig. 6.6).144 Only the figures of Diogenes and Heraclitus depart from the pattern, situated by themselves on the steps. The latter is the only figure properly seated, and he rests his head in his hand in a gesture of melancholy: He is often described as ‘the weeping philosopher’, and Diogenes Laertius said that he was unable to complete some of his writings because of melancholia.145 A painting of a laughing Democritus and weeping Heraclitus was kept in Ficino’s study in the Villa di Careggi, the official seat of the Platonic Academy, and such an iconography may have influenced Raphael’s representation of the gloomy philosopher.146 In Raphael’s fresco the philosopher is leaning on a large marble block, pen poised on the paper before him. He exists not in the dialogue, like most of the other philosophers, but in sealed isolation. He is represented as the withdrawn loner, engrossed in his artistic enterprise, transforming the stone into poetic words, forms, and fundamental truths. Unfortunately, the writing is not legible, but it so happens that one of Michelangelo’s earliest known poems corresponds very well to this image—and with the basic outlines of Heraclitus’ thinking. No complete work by this Presocratic philosopher survives, only fragments and other writers’ comments. His most important work was said to have begun with the phrase: ‘Although this account holds forever, men ever fail to comprehend, both before hearing it and once they have heard.’147 What is translated here as account is the Greek word logos, which can also be read as truth or reason. The claim is that truth only exists for and by itself, in the unspoiled presence of pure phenomena, never in prejudice or afterthought.148 It is interesting, also, that Heraclitus placed hearing (akoúō) above all else—above logic and the intellect. Other famous Herclitean sayings in the same vein are ‘everything flows’ (panta rhei) and that one cannot step into the same river twice. Michelangelo himself wrote:

Fig. 6.1 Raphael, School of Athens, 1510. The Vatican Museums, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

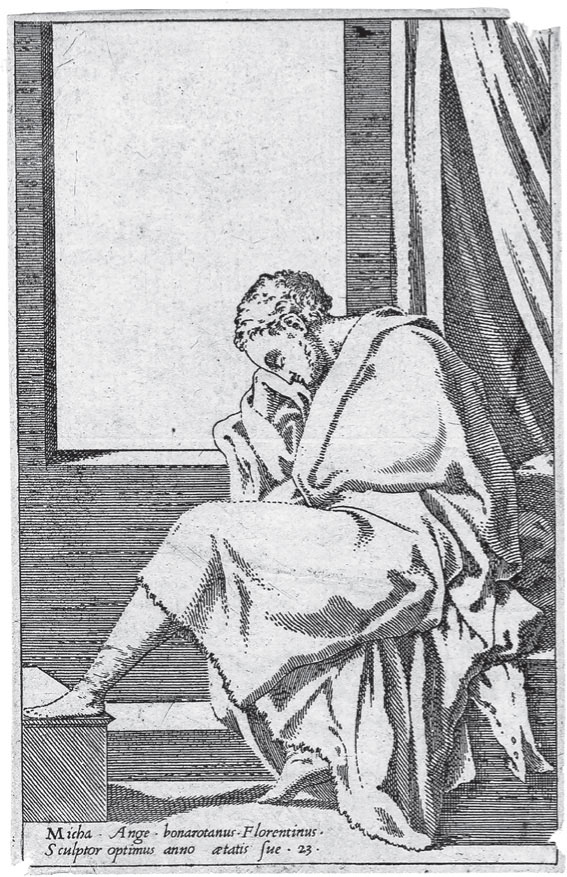

Fig. 6.2 Unknown artist, Portrait of Michelangelo at the Age of 23, 1498. Print. (Photo: British Museum)

One lives happily for many years,

in one brief hour suffers and laments.

Through famous or ancient lineage,

another shines brightly, and in a moment is darkened.

There is no moving thing under the sun

but defeated by death and changed by fortune.149

The content of the poem, especially the last two lines, is in line with Heraclitus’ ideas of flux and constant flow. Michelangelo often circulated his poems among his friends, so that it is not improbable that Raphael knew these lines or similar poems by the sculptor. Like Heraclitus, Michelangelo was often described as a melancholic.150 It is striking how well they function together, then, the images of Heraclitus and Michelangelo.

Fig. 6.3 Unknown artist, Portrait of Michelangelo, 1527. Print. (Photo: Peter Gillgren)

In other depictions of Michelangelo from the sixteenth century, the artist is represented in a similar fashion. A print claiming to be a portrait of Michelangelo at the age of 23, predating the image by Raphael by about twelve years, represents him sitting head in hand in an attitude of melancholy or sorrow (Fig. 6.2). He is dressed in classical robes and surrounded by architectural elements. A later print from 1527 shows him as a sculptor, energetically attacking a piece of marble with hammer and chisel, rearing up over the block like Nike triumphing over the great bull (Fig. 6.3).151 Behind him is a classical image of Venus and in front of him Hermes, symbols of worldly sensuality and the more abstract divine. Together the prints bring out the character of Michelangelo and his art; competing with the ancients, excelling in the art of sculpture, full of anxiety and melancholy, disturbed by the challenges of his predecessors and all the difficulties of his chosen medium—marble—and the constant struggle between material conditions and divine inspiration. Raphael introduced the latter topics in his fresco, and brought them both out in the figure of Heraclitus.

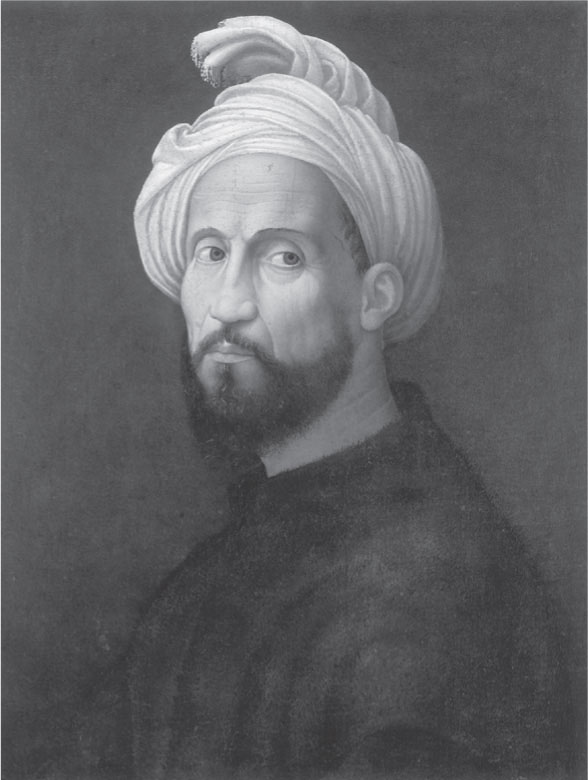

Michelangelo was not flattered by his rival’s portrait, however. Instead, he attacked Raphael for imitating his style and belittled him at every opportunity, as can be seen both in Vasari’s and Condivi’s biographies. No doubt he saw Raphael’s change of style as an appropriation, an attempt at challenging and emulating his own innovations. In painting the last prophet of the Sistine ceiling, he gave his own version of the thinker, the penseroso, now in the shape of the troubled Jeremiah (Fig. 6.4). In a sense this powerful figure is an aemulatio both of Raphael and his own previous work. It is certainly no portrait of his rival, nor yet an imitation of his style. Sometimes it has been taken to be a self-portrait.152 Behind the impressive figure stand two adult men, and not the putti that attend the other sibyls and prophets of the ceiling. The man to the left of Jeremiah looks so flat and is so badly painted that it is widely assumed this part of the fresco was done, repaired, or repainted by an assistant.153 The same figure was present in early prints of the painting, though.154 It is reminiscent of Raphael’s self-portrait in The School of Athens and could be read as a caricature of Raphael’s elegant, linear style. On the other side of Jeremiah, a man in a loose turban—such as those worn by sculptors when at work—has closed his eyes and is turning his head away in disgust. Michelangelo wore a similar outfit himself in the portrait by Giuliano Bugiardini of 1522 (Fig. 6.5). The constant and troublesome presence of aemulatio in Renaissance culture is the lens through which these portraits—if they may be called that—should be seen. The representations of Heraclitus and Jeremiah embody the unease felt by two artists, working at the Vatican Palace and the court of Julius II at the very same time and with equally high aspirations.

Fig. 6.4 Michelangelo, Prophet Jeremiah, c.1512. Sistine Chapel, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

Fig. 6.5 Giuliano Bugiardini, Portrait of Michelangelo, 1522. The Louvre, Paris. Oil on panel. (Photo: Scala Archives)

Fig. 6.6 Raphael, Detail from the School of Athens with Self Portrait, 1510. The Vatican Museums. Fresco. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)