CHAPTER 8

The tomb of Pope Julius II

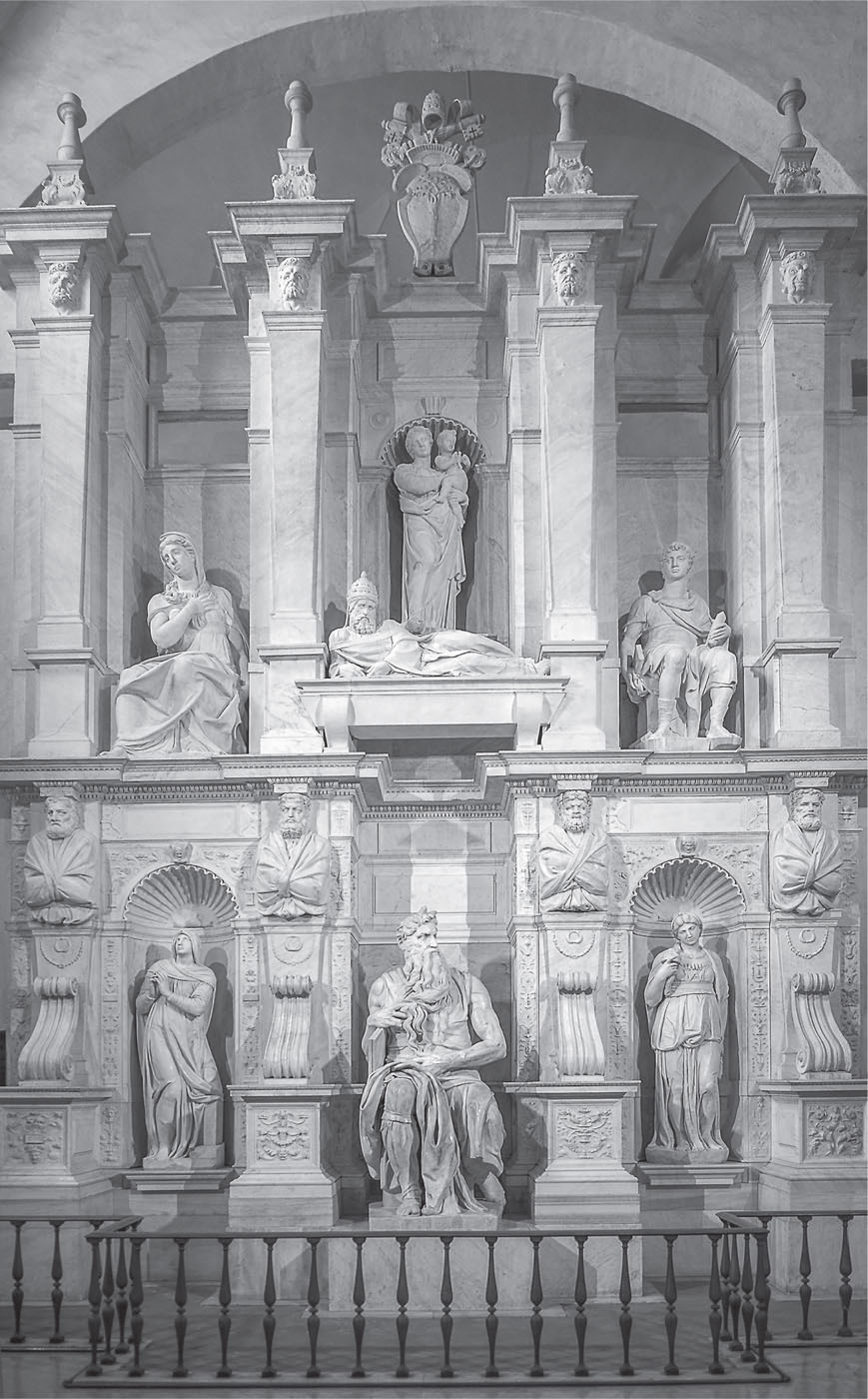

Returning to Rome in 1534, Michelangelo finally had the opportunity to complete the funeral monument for Pope Julius II. The tomb has often been treated as Michelangelo’s greatest frustration and disappointment in his artistic career (Fig. 8.1). The original commission by Julius himself of 1505 was interrupted and altered many times during the Pope’s lifetime, and came to an almost complete halt a few years after his death in 1513. After long and troublesome negotiations with the Julius’ family, the project was finally completed in 1545, forty years after the original commission, in a reduced format and in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli instead of St Peter’s Basilica. People were soon talking, like Condivi, about the ‘tragedia della Sepoltura’, and historians have focused on the discarded plans and frustrations of the project, from the original colossal monument to the final, more modest achievement.223

Vasari relates how Pope Paul III interfered in negotiations. Looking at the statue of Moses in the artist’s workshop, one of his cardinals exclaimed that this marvellous work of art was enough to do honour to Pope Julius—and Paul III agreed.224 Vasari added his voice to the chorus of praise, and went on to note that many Jewish families visited the completed monument on their Sabbath to honour Moses.225

Still, even though the plans were changed and discarded many times, it is important to remember that the project was seen to completion by the artist himself—which is more than can be said for many other of his commissions, including the Medici Chapel, the Capitoline Hill, or Saint Peter’s. Julius II’s tomb is thus a unique specimen for our understanding of how Michelangelo thought about the coordination and installation of sculpture at the site.

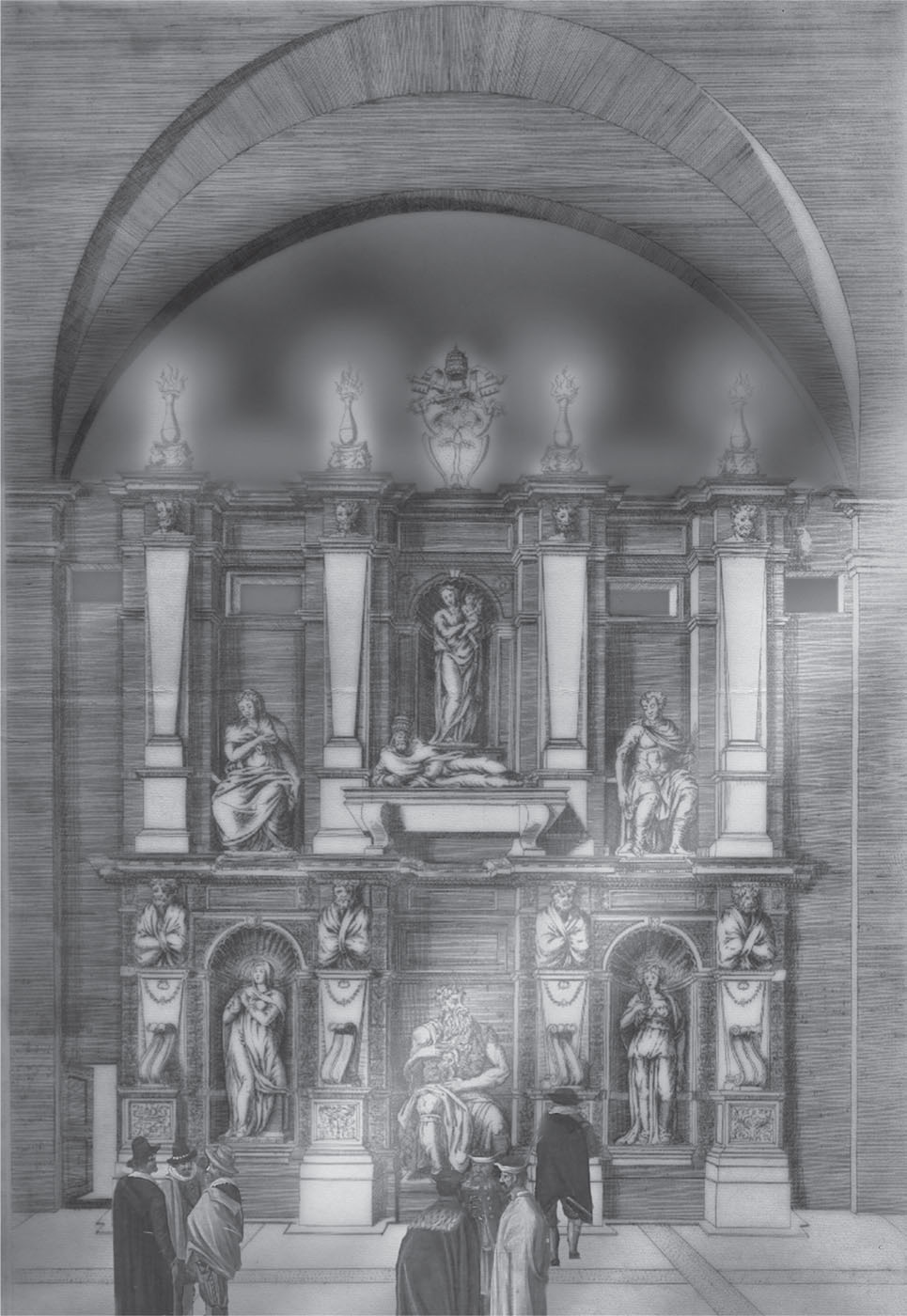

The sculpted figures of the lower register are Leah and Rachel, flanking Moses in the centre. In the upper register are a prophet and a sibyl on each side of Julius II, who reclines on his sarcophagus with a Madonna and Child in a niche above him. Since all of the seven figures are in the same plane it is difficult to speak of any spatial relationship between them. Nevertheless, they belong to the same site and therefore are intuitively expected to interact on account of a certain relational logic. The principle of such a composition is distributive rather than narrative.226 The figures are related as variations of a theme, rather than through interaction. They are understood as analogues, as united by family rather than by acquaintance. Material and style connect them, naturally, but above all it is their different positions that draws them together and directs the spectator’s attention.

Fig. 8.1 Michelangelo, The tomb of Pope Julius II, 1505–1545. San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. Marble. (Photo: Shutterstock)

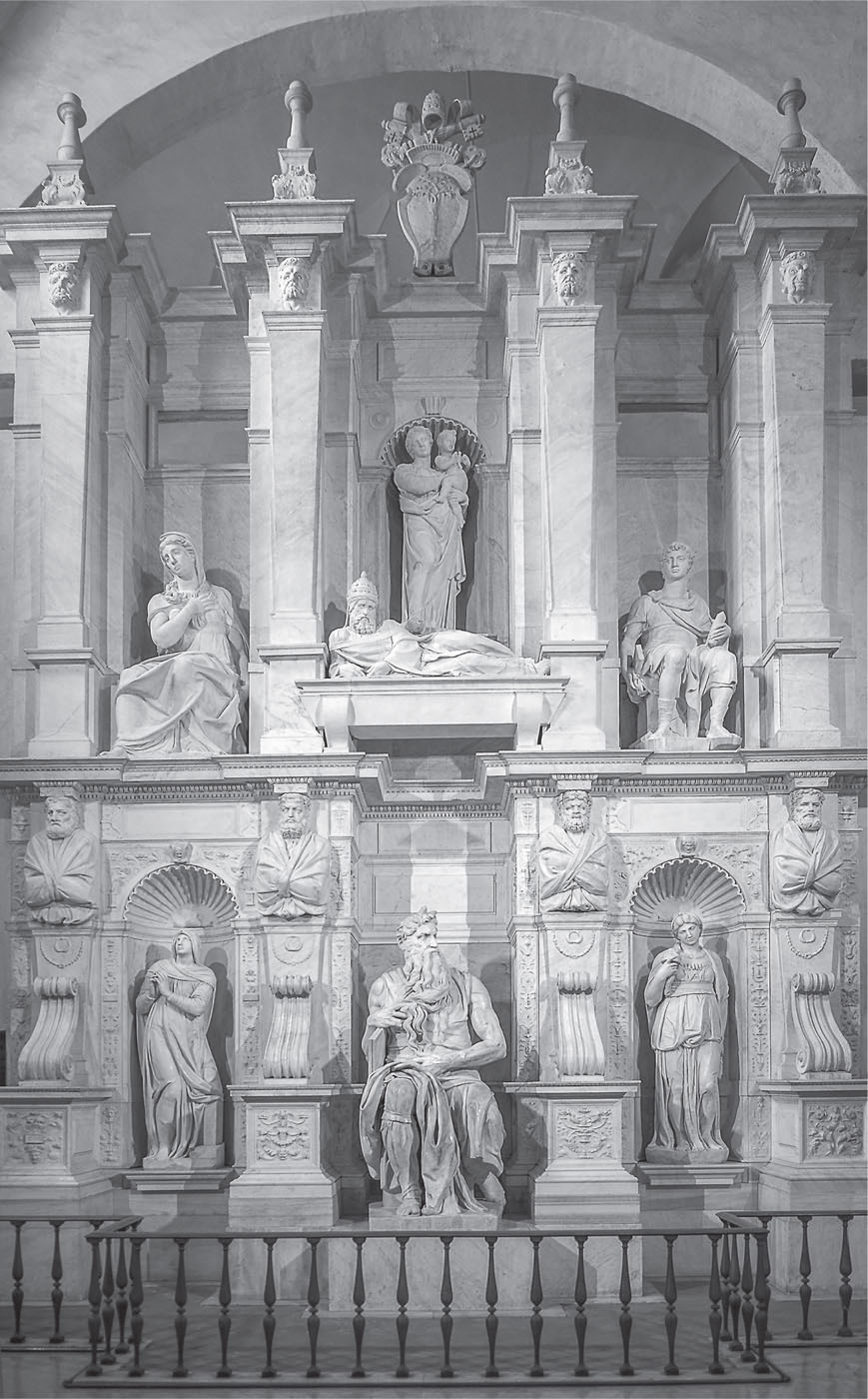

Moses has always been the point of greatest interest in the monument (Fig. 8.2). It is often assumed that this was the only part of the project executed by the artist himself, and with its magisterial, intense charisma it is seen as one of the foremost expressions of the terribilità that characterizes Michelangelo’s most powerful creations. Of all the analyses of the work, Freud’s is well known and influential. Freud took great interest in the visual arts and his teachings have greatly influenced art history along with all the humanities.227 It was when writing an essay on Moses during a stay in Rome in the autumn of 1912 that he made numerous visits to see the tomb.228 That said, it is clear that he also relied heavily on photographs—the tradition of photographic portraiture allowed for a strategic isolation of the object of study— although he is suspiciously silent on the topic, seldom mentioning his dependence on the photographic medium.229 Either he suppressed it, or, like many other moderns, he viewed the photograph as simply an extraordinarily exact and objective registration of reality, in no need of any particular considerations of its character and limitations.230 Photography was not understood as a method, but as the transparent and objective documentation of unvarnished truth.

On the other hand, Freud did comment on the character of his great interest in the visual arts. In his Moses article, he admitted that he had far greater difficulties with music:

works of art do exercise a powerful effect on me, especially those of literature and sculpture, less often of painting. This has occasioned me, when I have been contemplating such things, to spend a long time before them trying to apprehend them in my own way, i.e. to explain to myself what their effect is due to. Wherever I cannot do this, as for instance with music, I am almost incapable of obtaining any pleasure. Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me.231

Fig. 8.2 Michelangelo, Moses, 1505–1545. San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. Marble. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Apparently, he found music contrary to analytical reasoning and preferred literature and sculpture (and painting to an extent) because they gave greater opportunity for immediate reflection and analysis. This was probably also the reason for his preference for photographs, and for the disappointment he often felt when encountering works of art having prepared himself by studying them in reproduction from the safety of his desk at home.232 Photographs thus preconditioned his understanding of works of art, and served their purpose at the analytical stage, much like the patient notes he took during consultations. Confrontations with patients and works of art were essential and had a special status, but for academic work the text or the photograph was more important and evidential.233

Freud was certainly not alone in this; many of the great art historians both then and now were equally reliant on photographs. Adolfo Venturi, who spent over thirty years writing a rich and important survey of Italian art through the centuries, spoke openly about his generation’s dependence on photographs. A work such as his own would not have been possible without photos.234 The price was not only the colour—as was often recognised—but also the isolation of the work of art from its site, a solitude and stillness of the study object that has often given our discipline a certain restrained and melancholy character.235

In paying so much attention to his own responses to works of art, Freud potentially could have shown a greater interest in spectator perspectives in toto. Yet he insisted on the singular importance of artistic intentionality as the core issue of all such investigations. There is not even a nod to intuition, intertextuality, or practical circumstances; instead, ‘What grips us so powerfully can only be the artist’s intention.’236

Freud also admitted to a paradox: all great works of art produce bewilderment of sorts in their audience, and he could not enjoy that greatness until the mystery had been dispelled and fully explained. It was psychoanalysis that would provide such explanations, he claimed, and gave the example of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which was misunderstood for centuries until the Oedipus complex was brought into the debate and a satisfactory interpretation was finally given.237

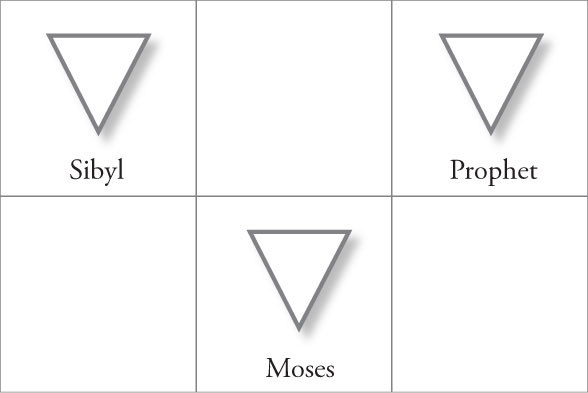

Fig. 8.3 Direction of standing figures of the Julius monument. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

Just as with his patients, Freud wanted to bring forth the subconsciousness of works of art, as if they were living beings. In the Moses essay, he took issue with all the contemporary experts on the art of Michelangelo: Herman Grimm, Carl Justi, Henry Thode, Ernst Steinmann, and others. The debate was somewhat curious, since the issue seems to have been whether Michelangelo’s Moses is about to rise up from his seated position or not. Several authors had indeed claimed that he is about to do so, but Freud disagreed:

I can recollect my own disillusionment when, during my first visits to San Pietro in Vincoli, I used to sit down in front of the statue in the expectation that I should now see how it would start up on its raised foot, dash the Tables of the Law to the ground and let fly its wrath.238

As this faux-naif expectation was thwarted, Freud instead went on to conclude that withheld anger was the most significant psychological feature of the work. The statue would not spring to its feet, but must be allowed to remain in its given position:

What we see before us is not the inception of a violent action but the remains of a movement that has already taken place. In his first transport of fury, Moses desired to act, to spring up and take vengeance and forget the Tables; but he has overcome the temptation, and he will now remain seated and still, in his frozen wrath and in his pain mingled with contempt.239

The question to be addressed, however, is how such an effect on the viewer is produced. What is it about this work that led Freud and so many others to imagine that a piece of marble had the power to get up and move about? Or to ask wrily, like Erwin Panofsky, what made him sit down in the first place, if he was so upset?240

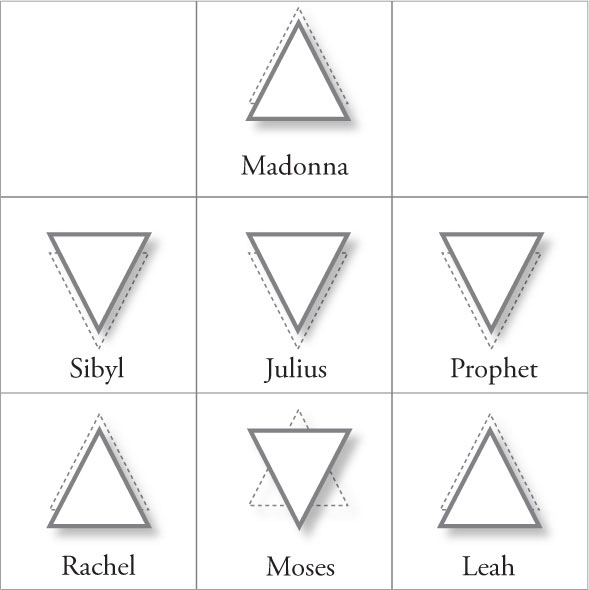

Fig. 8.4 Direction of sitting figures of the Julius monument. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

Instead of looking at Moses in isolation, it is essential to consider its immediate ambience and the site as a whole. Rather than relating to one another through their gestures and gaze, the figures of the monument engage in a logic, where they all appear as variations of one another and on the theme of standing, sitting, or lying down. In the lower register, the figures on the sides are standing, while the central figure is seated. In the upper register the figures on the sides are seated, while the figure between them is lying down. Above this recumbent figure stands the Madonna and Child. The three standing figures, Rachel and Leah in the lower register and the Madonna at the top, together form a triangle (Fig. 8.3); the three seated figures, Moses below and the Prophet and the Sibyl above, an inverted triangle (Fig. 8.4).

The composition thus combines the tensions of upward and downward forces with a strong dynamic. This is what produces the impression that the individual figures are not static, but moving in different directions and changing to adopt the position of the others. In the upper register, the seated figures are pulled downwards and seem just to have sat down. Even the reclining Julius II seems to represent the act of lying down rather than simply lying there. The Madonna seems to be moving as well, but not in order to sit down but rather to be lifted even higher, from standing to levitating. Michelangelo’s figures are seldom static—almost always in dynamic movement, they reach beyond their given positions.241 In the lower register, the figure of Rachel seems to be reaching upwards more than the others, while Moses is considering the same shift of position from his solid seatedness. Combine the standing and seated figures (Fig. 8.5), and one has the figural positions (dark triangles) and the figural movements (light triangles).

Fig. 8.5 Direction of all figures of the Julius monument. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

Plainly, the figures of the second register have the potency to strive downwards, towards the earthly, while those of the lower register seem to be on their way upwards, towards the heavenly and more abstract. At the centre of the composition, different movements meet, and the upward movements of Moses and the Madonna, the patriarch and the utmost allegory of heavenly love, are contrasted with and tempered by Julius II’s horizontal, half reclining position, lending a vertically levitating power to the gisant on its sarcophagus. In sum, the following individual movements are represented: three figures seated, two standing, one lying down, and one levitating. The most common position is to be seated, while to be lying down or levitating are the extremes. Moses is in several ways overdetermined. Not only is he on the lowest level and surprisingly close to the approaching spectator, he is also seated, which is the overrepresented pose; at the same time, he is about to get up, being the figure imbued with the greatest capacity to alter position. Further, Moses is seated in the central bay of the monument, and the statues above him are in extreme attitudes, lying down and floating upwards. The figures of the monument thus work on the spectator’s attention, focalizing on the seated Moses and charging him with energy and the potency to rise from his seat. This is achieved through a conscious, consistent analogy between the sculpted figures—a logic of site that replaces narratology as a dramaturgical tool.

As early as Vasari and Condivi, Leah and Rachel were read as allegories of vita activa and vita contemplativa.242 This is in accordance with a passage in Dante, who wrote that Leah enjoyed decorating the house and making beautiful flower arrangements, while Rachel was fonder of watching her sister’s results.243 The idea goes back to Gregory the Great, who was possibly the first to compare the Old Testament sisters with the figures of Martha and Mary in the New Testament, writing in a personal letter that he himself had always

loved the beauty of contemplative life as a Rachel, barren, but keen of sight and fair, who, though in her quietude she is less fertile yet sees the light more keenly. But, by what judgment I know not, Leah has been coupled with me in the night, to wit, the active life; fruitful, but tender-eyed; seeing less, but bringing forth more.244

The Leah of Julius’ tomb is the more decorated and directs her attention downwards, towards the earthly. She is the introvert, focused on her own concerns. Rachel is more serene, with veiled hair and little ornament, but with an attentive, extrovert gaze directed upwards. She is already halfway part of the register above, where the anonymous Sibyl and Prophet signal the coming of Christ. Between Leah and Rachel sits Moses, the centrepiece of the monument, turning away from the spectator and towards Leah’s activities. The relation between the three Old Testament figures is the same as that between a spectator, an artist, and a work of art: Rachel, the spectator, gazes fondly at the more abstract qualities of the work, while Leah, the artist, loses herself in attention to detail.

The arrangement with the two contrasting levels of architecture is one of the themes to have survived from the original plan. In his influential study, Panofsky accorded great importance to what is admittedly a rather conventional structure.245 In analysing the monument he mixed elements from all the different planning stages, so that it is hard to know which conception of it he was really referring to. His principal idea was nevertheless clear—that the composition was founded in Neoplatonic thought and symbolism:

In the Tomb of Julius … heaven and earth are no longer separated from each other. The four gigantic figures on the platform, placed as they are between the lower zone with the Slaves and Victories and the crowning group of the two Angels carrying the bara with the Pope, serve as an intermediary between the terrestrial and the celestial spheres. Thanks to them, apotheosis of the Pope appears, not as a sudden and miraculous transformation, but as the gradual and almost natural rise; in other words, not as a resurrection in the sense of the orthodox Christian dogma, but as an ascension in the sense of the Neoplatonic philosophy.246

Panofsky was referring here to a version of the monument that never existed. As for the one that was actually built, he was extraordinarily critical:

The final result bears witness not only to an individual frustration of the artist, but symbolizes also the failure of the Neoplatonic system to achieve a lasting harmony between the divergent tendencies in post-medieval culture: a monument to the ‘consonance of Moses and Plato’ had developed into a monument of the Counter-Reformation.247

Yet there is more to say about the final composition than Panofsky cared to admit. An important characteristic of the monument is the manner in which the difference between the two registers is enhanced by the elaborate ornamentation of the lower. Its generous ornamental style harked back to the early sixteenth century and monuments such as that to Andrea Sansovino in Santa Maria del Popolo. In great contrast, the upper part is unadorned. This could reasonably be understood as the artist contrasting earthly existence with the Platonic ideals of pure abstraction and eternity.

In Michelangelo’s poetry, the same dualism was often present as a kind of contrapposto.248 The earthly was set against the divine, hate against love, and the base vices of the body against the virtuous spirit. This duality was seldom as simple and one-directional as in conventional Neoplatonism, however. There was a complexity, where the earthly not only strove for higher abstraction, but at the same time longed to see the abstract become a reality, and proximate too. An example is Sonnet 156 from about 1540, around the time of the completion of Julius’ tomb:

To the height of your shining diadem

from the long and winding road

there is no one who can reach you

if humility and kindness are not added;

the ascent increases, and my strength weakens,

and I am short of breath halfway along the route.

That your beauty should still be

celestial, brings joy to my heart,

which for all things rare and lofty shows greed;

but then, to enjoy your loveliness,

I still yearn for you to descend

to where reachable. And this thought comforts me

as I predict your anger

for loving your lowliness, hating your haughtiness:

that still you will pardon my sin.249

The poet longs for his donna of the higher spheres, but he also asks on her behalf that she be filled with humility and courtesy (‘umilta’ and ‘cortesia’), to come down to a level where he can reach her (‘discenda là dov’aggiungo’). Finally, he excuses his feelings, for loving her when she is low, and not being appreciative enough of her higher existence. The same dialectics are present in the tomb: the sensual, graceful beauty of the lower register has refined qualities, compared to the cooler elegance of the upper part. This was probably true in the earlier versions as well, where the famous and uncompleted slaves were to be placed in the lower register.

Charles de Tolnay noted that the monument’s primary viewpoint is not frontal, but rather from the left-hand side of the monument, as seen when approaching it from the right aisle of the church.250 The central figure of Moses then appears to turn his head to meet the viewer, rather than avoiding the viewer’s gaze. His welcoming gesture is similar to those of the Captains of the Church in the Medici Chapel.

A recent restoration of Moses has emphasized the important alterations made by Michelangelo before siting the statue.251 Most importantly, the face was recut from looking forwards to sidewise in order to adapt him fully to the composition of the monument. This left the figure turning his gaze away from the spectator in front of the monument, towards the side aisle with a small window (today blocked up) and the morning sun. A Moses that looked straight ahead would have given a more banal, less dynamic impression, and the changes gave the entire monument a double vista, even though the view from the nave must be considered the more important—it has a full panorama of the whole ensemble, with the two principal registers of architecture and the seven full-size sculpted figures arrayed on them. The monument is surprisingly close to the ground, raised only by a low foundation and bringing the approaching spectator very close to the three lower figures.

An unusual feature that is seldom commented on is the enclosure: the architecture of the upper part has no cornice or other form of horizontal finish. Instead, it is crowned by four candlesticks standing on consoles decorated with mascarons. The large lunette window above (recently opened up having been blocked up for many years) extends across the three aisles of the monument, and together with four rectangular windows opens onto a room behind. Vasari informs us that the brothers of the cloister had a chapel behind the tomb, and that the openings were there to enhance and mediate their prayers and song, serving ‘to send their voices into the church’.252

The human voice was held in special honour in the Neoplatonic system. Marsilio Ficino followed Plato in his high regard of the spoken word, and indeed Aristotle’s idea of the human voice as a ‘sound produced by a soul’. Singing was especially revered, combining as it did poetry and music in the personal expression of the individual voice. Ficino even spoke of song as producing ‘animated’ or ‘spirited air’, with a particular capacity to move the human soul.253 From a Neoplatonic viewpoint, the openings in Michelangelo’s monument were more than meaningless voids, and should be understood as significations of the spirited air that was meant to echo from beyond.

The tomb of Julius II went through several stages before it was given its present appearance, of course. Initially it was free-standing with four sides, forming a small chapel of its own within the walls of St Peter’s (or perhaps in a purpose-built mausoleum). A later, less extravagant, but perhaps more practical plan was to build it against an existing wall of the church, so retaining the sense of a small chapel. Later on, the three walls were further simplified, but even in its final execution the idea remained of having the tomb built as if it were a small chapel for prayers and singing. Even though unusually well composed, the arrangement was not unique among the many funerary monuments in Rome of this time.

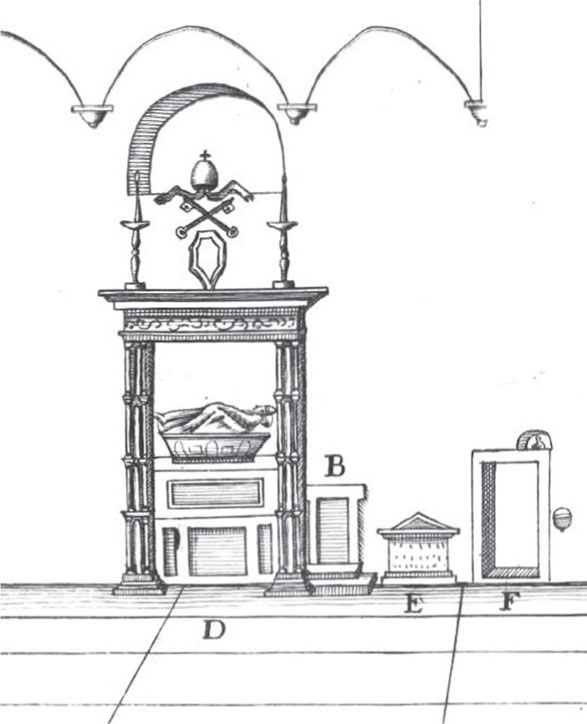

In two letters of 1525, Michelangelo mentioned that it was now certain that the monument would be built as a wall tomb, similar to those of Pius II and Pius III.254 It is curious that he should have mentioned these rather simple, old-fashioned monuments, when there were so many others which at first glance were much closer to his own project. Of the tombs of the Piuses, which were still in St Peter’s Basilica at the time (in 1614 they were removed to Sant’Andrea della Valle in the centre of Rome255), the more famous was that of the Piccolomini Pope Pius II, attributed to Paolo Romano and made for Old St Peter’s in the mid-fifteenth century, while Pius III’s was modelled upon its predecessor some decades later.256 Prints and drawings of their original placement show that Pius II’s was on the inside of the entrance wall of the church, on the left-hand side when entering (Fig. 8.6), while Pius III’s was just around the corner, at the eastern part of the southern aisle. Above it was a large lunette window, opening onto a chamber behind what was referred to on a plan of the church from 1614 as the Oratorio Anticho, or Old Oratory.257 The relationship between the tomb, the lunette, and the oratory is the most striking similarity between these tombs and Michelangelo’s project, and it could very well be the reason why the Pius monuments came to be mentioned in Michelangelo’s correspondence when it was decided that Julius II’s should be a wall tomb. In Michelangelo’s work, the relationhip between the window, the chapel behind it, and the monument is stronger and all is more clearly conceived as a single unit, but the effect of the sound carrying between the different spatial units is the same: to the sculptural and architectural levels is added a soundscape level.

Fig. 8.6 Anonymous, The Tomb of Pius III in Old Saint Peter’s, c.1503. From De Sacris Aedifici by Giovanni Ciampini, Rome 1693. Print. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Panofsky did not sufficiently acknowledge the signficance that Ficino attached to Moses, probably because he had so little interest in the monument in its final form. For the Neoplatonist, Moses was an important representative of the prisca theologia—the eternal wisdom that transcends all religious difference—together with such figures as Zoroaster, Hermes Trismegistus, and Orpheus.258

Panofsky’s Moses was a great political leader and a man who ‘saw with the inner eye’.259 According to the Old Testament, however, Moses was above all the powerful listener of the Israelites, transcribing the voice of God into the holy texts of his people. Where others could not bear the voice of their jealous God, he alone had the capacity to hear and take down the Ten Commandments in writing:

And all the people saw the thunderings, and the lightnings, and the noise of the trumpet, and the mountain smoking: and when the people saw it, they removed, and stood afar off. And they said unto Moses, Speak thou with us, and we will hear: but let not God speak with us, lest we die. And Moses said unto the people, Fear not: for God is come to prove you, and that his fear may be before your faces, that ye sin not. And the people stood afar off, and Moses drew near unto the thick darkness where God was. (Exodus 19: 18–21)

Moses’ revelation of God is one of the classic examples of religious ecstasy, where hearing and seeing are intermingled in a synaesthetic experience. In the Bible, the voice of God was seen rather than heard, prompting early commentators such as Philo of Alexandria to conclude that ‘the voice of men is audible, but the voice of God is visible’; it was also admirable that the voice of God proceeded from the fire, he continued, ‘for the oracles of God have been refined and assayed as gold is by fire’.260 Prophetic experience was by definition synaesthetic, he claimed. It was a matter of seeing the divine voice, hearing the divine light.261

Other early Christian writers would ask what precisely Moses saw when he entered ‘the thick darkness’ of the mount. The first satisfactory answer was given by Gregory of Nyssa, who explained that the Israelites were not yet ready for the deeper verities, but had to make do with the Ten Commandments and the Earthly Tabernacle. Moses, on the other hand, had prophetically seen into the future and experienced the more fundamental truths of the Heavenly Tabernacle and the coming of Christ: ‘For the prophetic eye, attaining to a vision of divine things, will see the saving Passion there predetermined.’262

Fig. 8.7 The tomb of Pope Julius II in San Pietro in Vincoli. (Reconstruction: Petter Lönegård)

This is how Michelangelo’s Moses was iconographically related to the Madonna and Child above—and ultimately also to the Papacy and to the figure of Pope Julius himself: it is the relationship between a visionary and his prophetic vision. And again this underscores the importance of the figure’s relationship to the sounding voices and musical chanting at the site. It is easy to imagine a small a cappella ensemble, invisible in the dark void behind, their disembodied voices carrying out through the openings in the tomb, which is lit by the burning candles of the lunette. Suddenly the figures all appear to be listening attentively, each in their own way, to the monument’s song.

The shifting positions and the feelings observed in the figures hint at their inherent meaning, as the soundscape of song, recitation, and prayer streams out to swirl around the figures. Moses no longer looks so severe, just somewhat surprised and full of expectation (Fig. 8.2).

The changes made once Moses was to be included in the tomb were indeed crucial for the overall expressiveness of the monument. The double vista so constructed would have made the sixteenth-century viewer relate not only to the internal relationships of the monument, but to a number of exterior factors too: Moses’ gaze falling on those approaching up the aisle, the light falling from the small window onto Moses’ face, and the presence of the resonant soundscape (Fig. 8.7). Pace Freud and Panofsky, Michelangelo’s Moses seems most of all to be listening to the voices around him. In the words of Condivi, who may well have experienced the work as the sounding object it was once conceived to be, Moses is ‘sitting there in the attitude of a wise and thoughtful man’.263 No doubt, Condivi was alluding here to Ficino’s and ultimately Plato’s idea of the sage as a person who lives near to God in a philosophical tranquillity that transcends the futilities of everyday life.264

The Moses of the tomb of Julius II is not angrily watching his sinful people dance around the Golden Calf. They are nowhere to be seen. Instead, it is a monument to synaesthetic ecstasy, of looking and listening so attentively for the sublime presence of God that the senses are mixed and all media borders are blurred.