CHAPTER 10

The cave of Vulcan

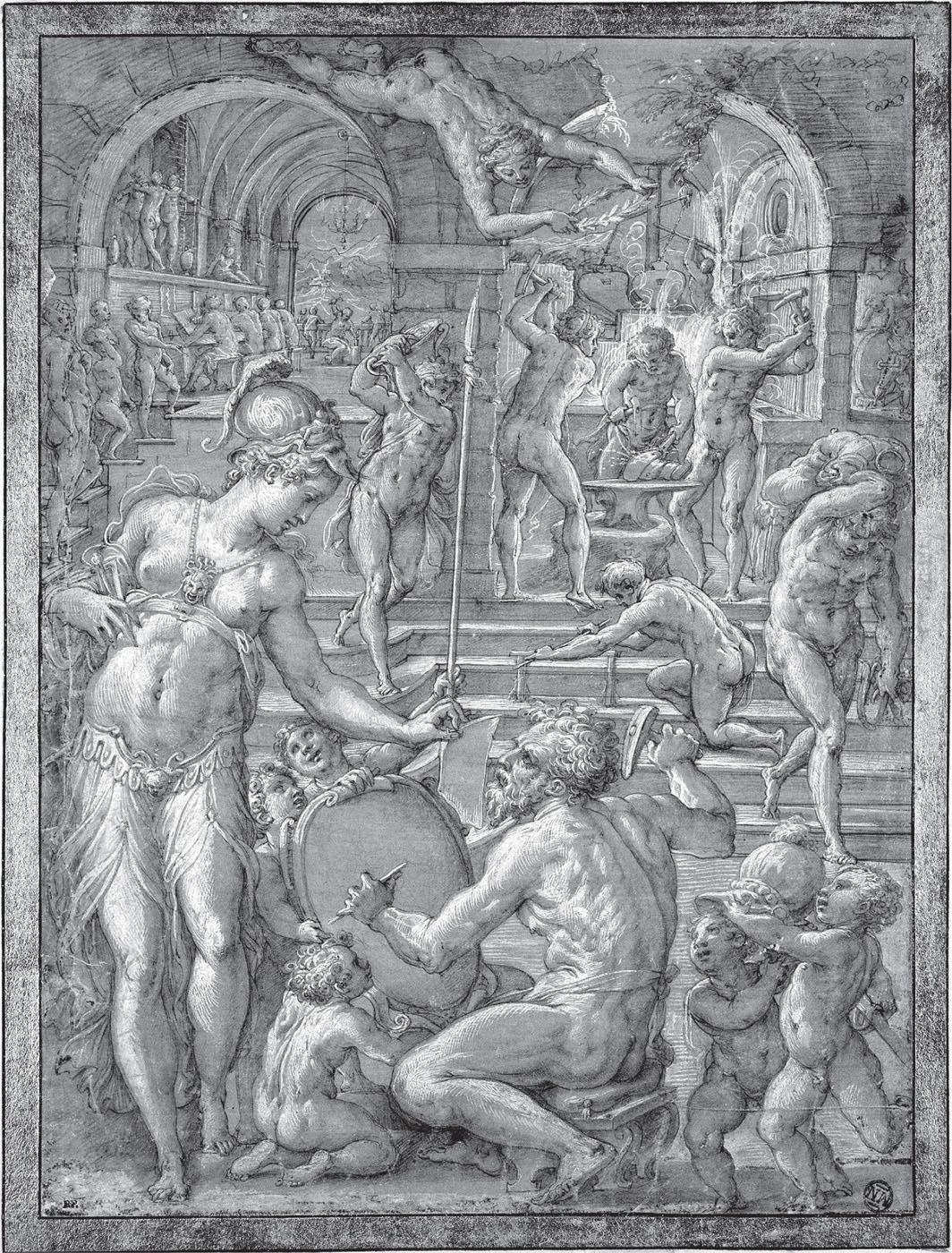

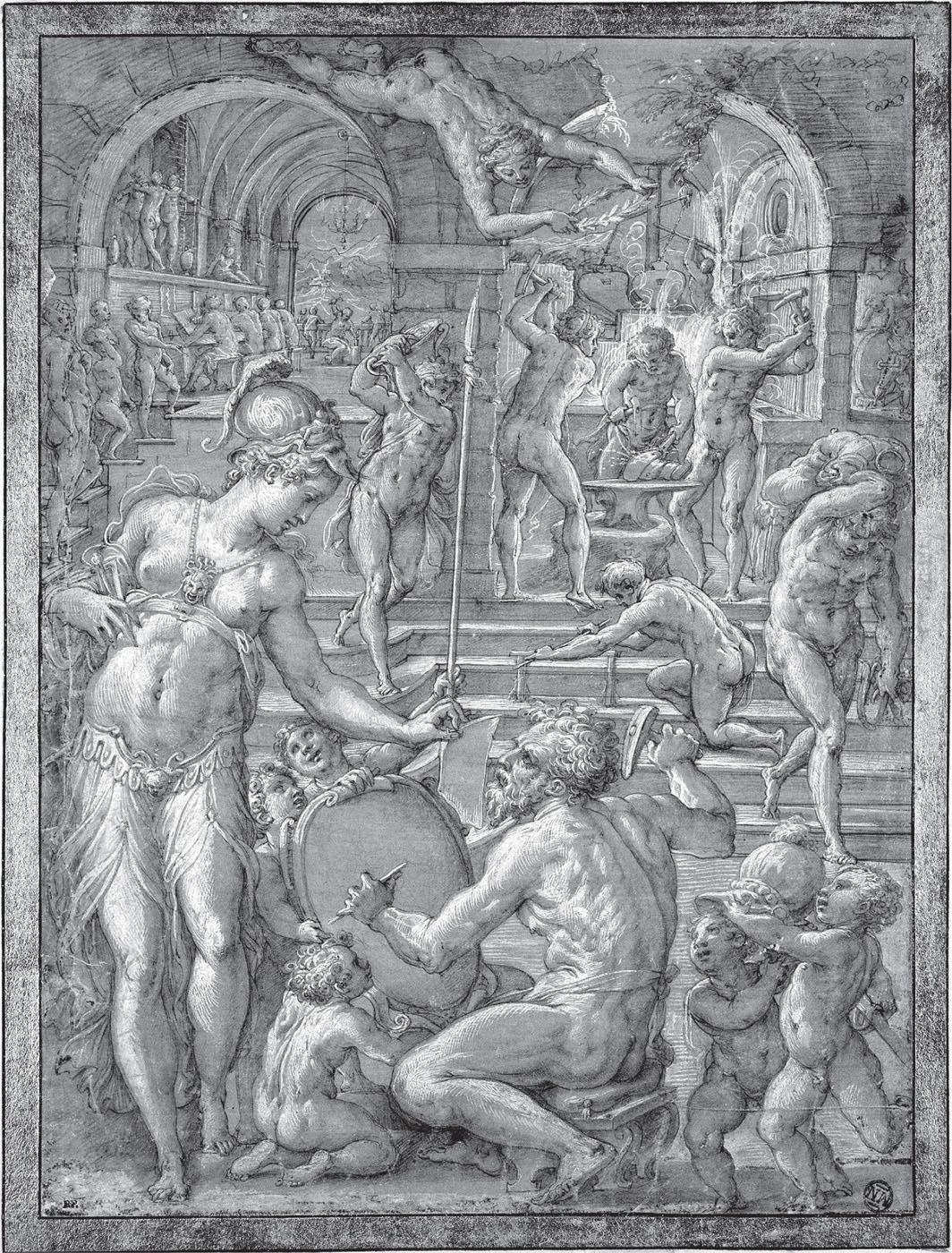

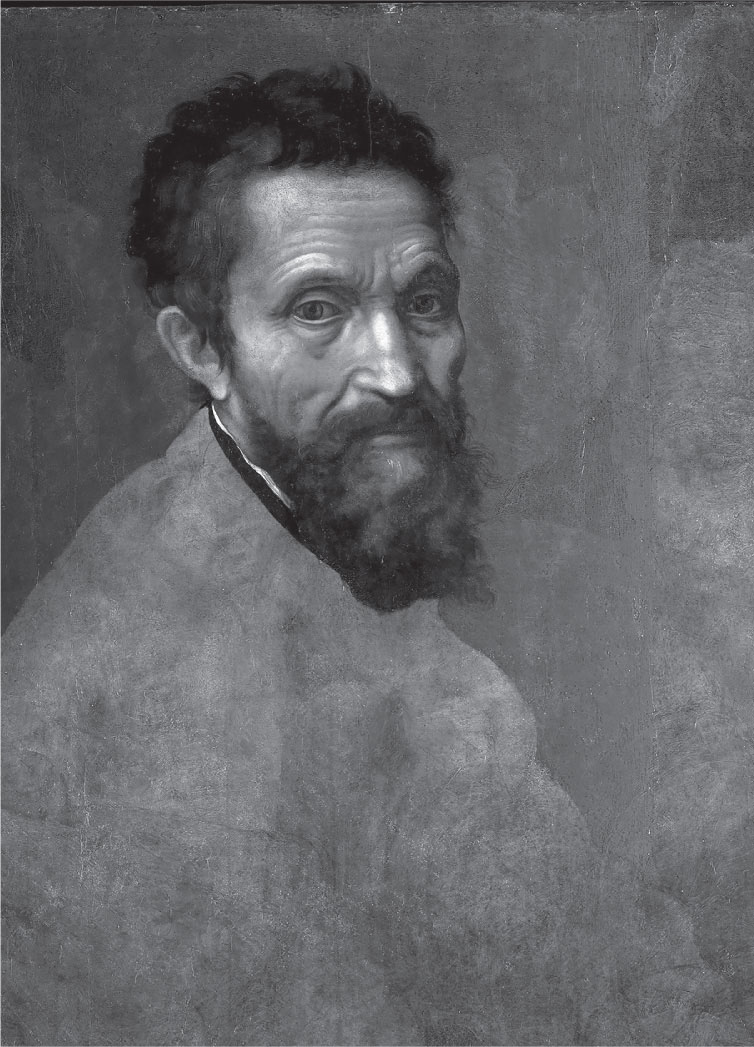

There is a drawing by Giorgio Vasari from c.1567 that represents the cave of Vulcan, Vulcan’s Forge at the Louvre (Fig. 10.1).279 A pillar divides the background into two vaults, on the one side a forge, and on the other an academy of quiet draftsmen, drawing from the famous ancient sculpture, The Three Graces. In the foreground, Vulcan is seated with hammer and chisel, working on a shield, helped by putti assistants who carry a helmet and a spear. Before Vulcan stands the figure of Minerva, presenting him with a small piece of vellum with instructions for the work. While Minerva is represented as a figure of classical beauty, her helmeted head in profile and graceful in stature, the figure of Vulcan is rather awkwardly seated at her feet. Part of his inelegance is no doubt the result of Vasari’s decision to model him on the Belvedere Torso in the Vatican, and his efforts to make the prototype immediately recognizable. He has taken pains to represent the torso from one of the best-known points of view, its back turned to the spectator. It is generally agreed that the Belvedere Torso served as a model for many of Michelangelo’s works, while the head of Vulcan looks very much like a portrait of Michelangelo himself (Fig. 10.2). Vasari’s intention seems to have been to highlight the relationship between the figure of Vulcan, the art of sculpture, and the artist Michelangelo.

The iconography of the drawing was not entirely Vasari’s own invention. Vincenzo Borghini gave instructions in an undated letter written in the late 1560s;280 it is usually assumed that this was part of Borghini and Vasari’s dialogue about the design of the Studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio, although most of that correspondence was slightly later in date. In a letter of October 1570, for example, Borghini summarized the idea of the Studiolo as a site for things that ‘are not solely of nature nor of art, as, for example, nature gives us diamonds, carbon or crystals and similar other materials, rough and without form, and art cleans them, reforms them and carves them’.281 The iconographic programme of the Studiolo included a statue of Vulcan, but no composition similar to Vulcan’s Forge is mentioned. In the earlier letter, Borghini starts by stating that he wanted a painting of Vulcan making the arms for Achilles, supervised by Thetis. But ‘as we have discussed together’, he wrote to Vasari, ‘I want to replace Thetis with Minerva, representing the art of painting’.282 Besides the forge, he also wanted to see an ‘academy of certain virtuosi who are practising drawing under the protection of Minerva’.283 It should be noted that it is Minerva/the art of painting who guards and protects disegno, not the other way around. Praxis is the protector of the idea, not vice versa. Furthermore, the draftsmen are busy learning by copying The Three Graces, an ancient sculpture. Their reflection and precision are coupled with the energy and flow of the smiths. In Vasari’s vita of Michelangelo there is a passage with striking similarities to the ideas evident in Vulcan’s Forge. In commenting on Michelangelo’s many lost drawings, Vasari’s mentions that the artist himself destroyed many drawings and cartoons, although they were very highly sought-after. Vasari, however, secured a few of them for himself, and kept them with his collection of drawings in an album. They were evidence, as he said, of Michelangelo’s ‘great genius, yet prove also that the hammer of Vulcan was necessary to bring Minerva from the head of Jupiter’, referring to the ancient myth of Minerva being born from the head of Jupiter with Vulcan’s help.284 Both in drawing and in writing, Vasari makes it clear that abstract humanist ideas were not sufficient to produce great art; industry and manual work were also necessary. Furthermore, ideas do not come about by themselves, but are in many respects the product of artistic diligence. Minerva may be the supreme protector of the fine arts, but she is brought to life herself only through the efforts of crafty Vulcan.

Fig. 10.1 Giorgio Vasari, Vulcan’s Forge, c.1570. The Louvre, Paris. Pen drawing. (Photo: RMN – Grand Palais)

Fig. 10.2 Daniele da Volterra, Portrait of Michelangelo, c.1544. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Oil on panel. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Michelangelo’s poetry, the forge occurs several times as a metaphor for the arts. Sonnet 62 discusses artistic creativity, beginning with the statement that ‘only with fire will the smith shape the iron from conception into fine, beloved work; nor without fire can any artist refine the gold to the highest degree’.285 Sonnet 46 is entirely devoted to same theme:

If my crude hammer shapes the hard stones

into one human appearance or another,

deriving its motion from the master who guides it,

watches and holds it, it moves at another’s pace.

But that divine one, which lodges and dwells in heaven,

beautifies self and others by its own action;

and if no hammer can be made without a hammer,

by that living one every one is made.

And since a blow becomes more powerful

the higher it is raised up over the forge,

that one has flown up to heaven above my own.

So now my own will fail to be completed

unless the divine smith, to help make it,

gives it that aid which was unique on earth.286

Just as the blacksmith bends the iron to his will with the help of fire, the artist needs the heat and smoke for his creative works, rendering and refining the material in accordance with certain concepts and ideas. In the famous lines of Sonnet 151 the same idea is put more clearly, and in direct relation to art: ‘Not even the best of artists has any conception, that a single marble block does not contain.’287 Like Vulcan, the sculptor must go underground, deep down into nature’s hidden secrets, if he is to succeed. He is drawn to the earth, to a site of noisy hammering and darkness, in order to bring forth the bright sparks of artistic creativity. The French diplomat Blaise de Vigenère left an eyewitness account of Michelangelo’s studio, reminding us again of the physical and noisy character of his art:

I saw Michelangelo at work. He had passed his sixtieth year and although he was not very strong, yet in a quarter of an hour he caused more splinters to fall from a very hard block of marble than three young masons in three or four times as long. No one can believe it who has not seen it with his own eyes. And he attacked the work with such energy and fire that I thought it would fly into pieces. With one blow he brought down fragments three or four fingers in breath, and so exactly at the point marked, that if only a little more marble had fallen, he would have risked spoiling the whole work.288

The metaphor of Sonnet 151 is Platonic in a sense, and is often taken as such, emphasizing the importance of having an idea (or a concept) in order to realize a work of art. However, it also sets out the restraints of nature: the marble block already contains all that can be said by the artist, much like a city is dependent on its hinterland, its surrounding landscape, and the thetic always stands in direct relation to the chora. There are no artistic concepts or abstractions that will ever go beyond what is given by nature.