CHAPTER 11

David

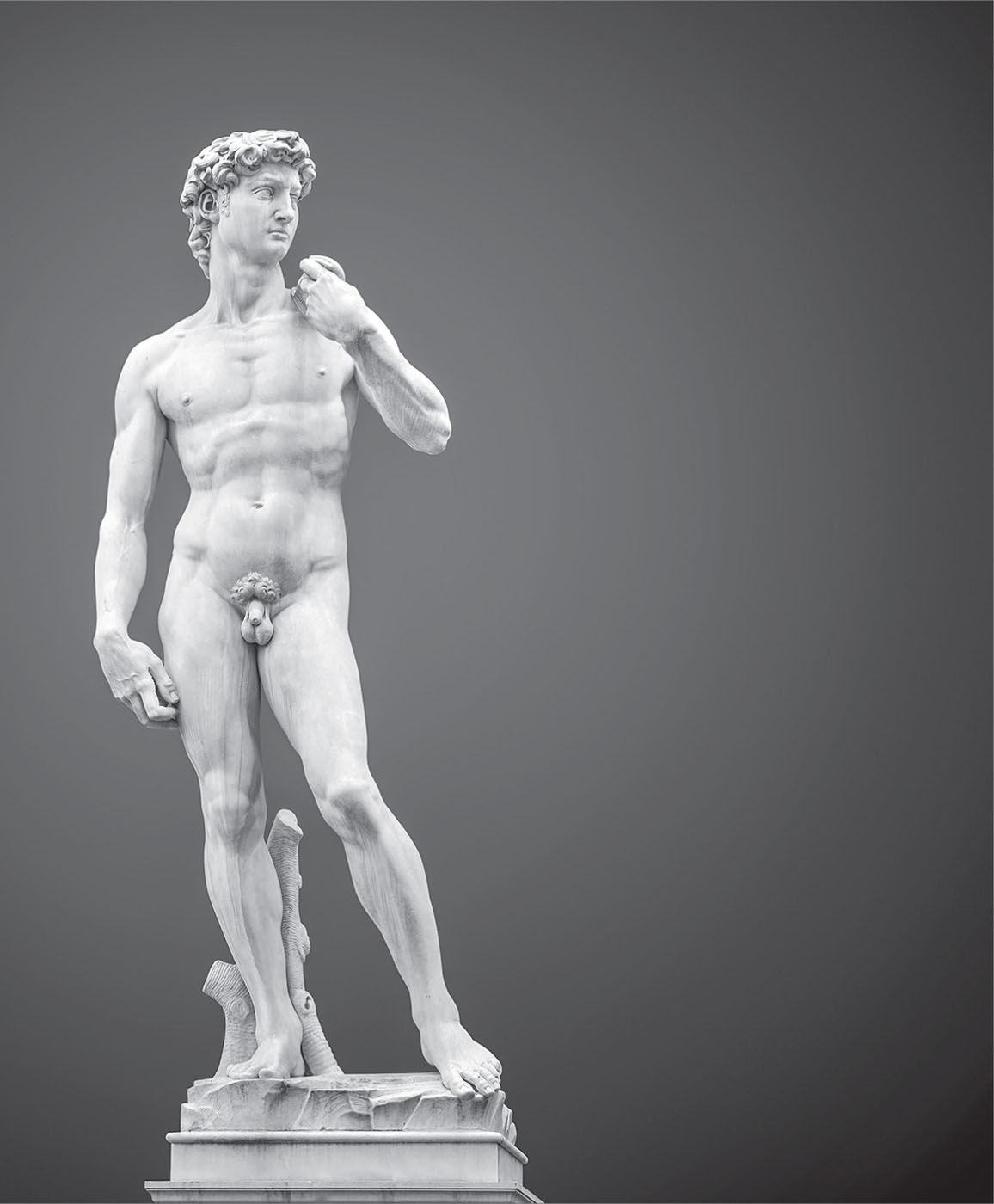

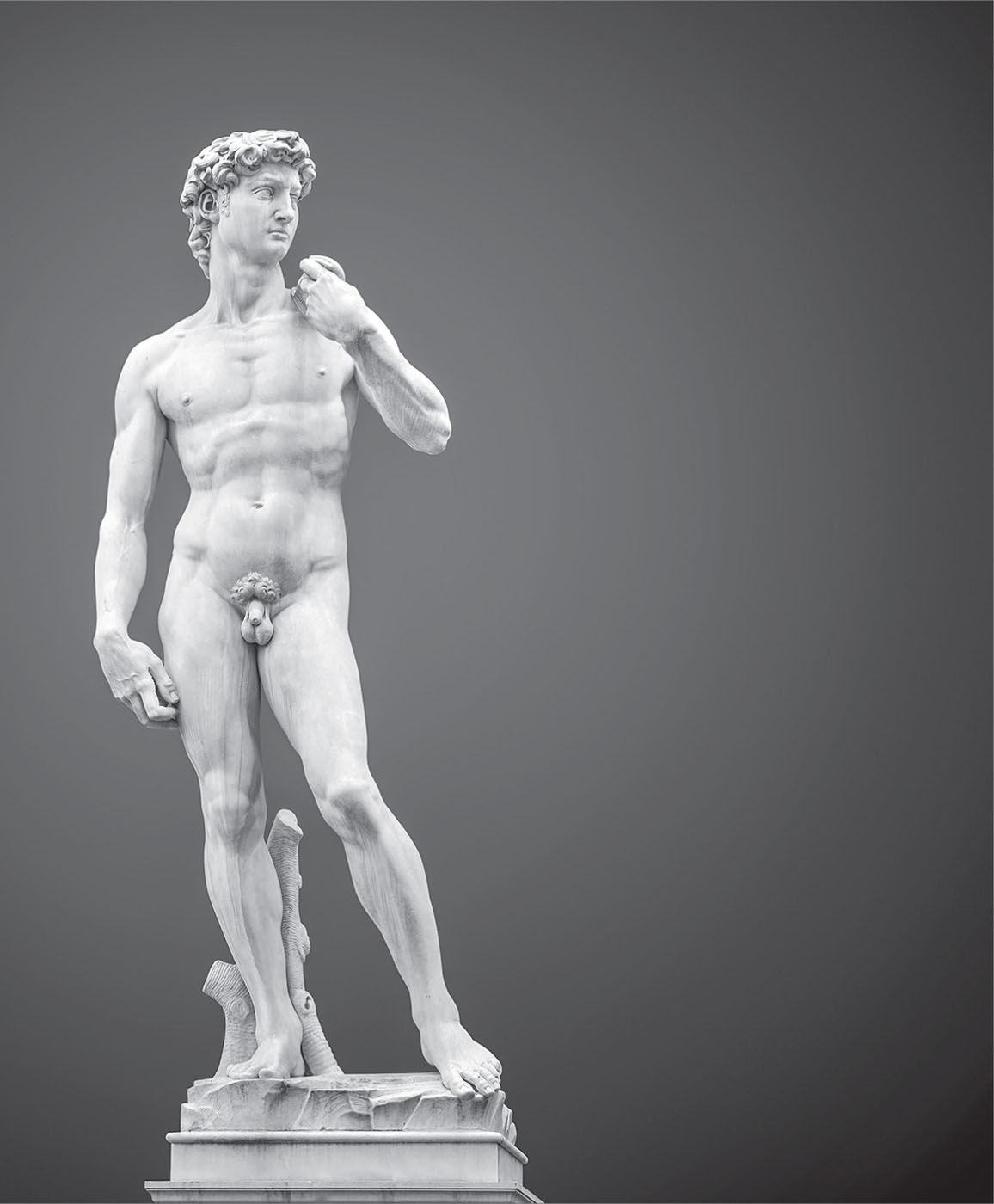

One of Michelangelo’s earliest artistic triumphs was the sculpture David in Florence, a work that was produced from an old block of Carrara marble sitting in the workshop yard of Santa Maria del Fiore (Fig. 11.1). The unusually high but all too shallow block had been in the Office of Works’ possession for quite some time, but they still had great difficulties in determining what to do with it. Other artists had suggested that pieces of stone should be added to make it more useful, but Michelangelo insisted that a beautiful figure could be carved without any additions.289 This was a winning argument, and he received the commission in August 1501.290 His success with David and the importance attached to the work being carved from a single block without additions can be explained by a deep respect for sculpture’s origins in nature, and how sculpture was expected to retain traces of its own origin.291

In January 1504, a council of the most eminent artists of the city gathered to discuss the siting of the work, Sandro Botticelli, Jacopo Sansovino, and Leonardo da Vinci among them.292 Finally it was settled, in accordance with a suggestion by the painter Piero di Cosimo: Michelangelo himself should decide, for ‘he who made it surely knows better than anyone the place best suited to the appearance and character of the figure’.293 The artist chose the north side of the entrance from the Palazzo Vecchio.294 The siting is perfect for the figure, with his back against the rough wall, so that the shallowness of the block and the relief-like character of the sculpture is emphasized without becoming disturbing. It displays the sculpture’s most striking features—the profile, the strong hands, the amazing height—and it both attaches it to and withdraws it somewhat from the piazza, the loggia, and other works of art nearby. Even the pedestal was given careful consideration; quite low, almost unadorned, and with obvious connotations to the display of classical sculpture.295 There are fascinating accounts of the immense difficulties of transporting the sculpture from the cathedral workshop to the Palazzo Vecchio in May 1504.296 A special system of beams and ropes on rollers had to be constructed, a gateway had to be destroyed, and enemies of the project threw stones at it, intent on damaging it.297 More than forty men were needed for the transport, which took four days in all.

Fig. 11.1 Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Marble. (Photo: Shutterstock)

The successful struggle with material preconditions is still an important part of David’s impact (it was moved to the Accademia delle Belle Arti in 1873, with a copy taking its place at the original site): the beauty of the material and the statue’s unusual height and detailed proportions continue to impress, while the constraints of the marble block are felt most strongly in the relief-like quality and rectangularity of the figure. Condivi makes an important point here:

Michelangelo accepted it [the block of stone], and without any other pieces carved from it the above-mentioned statue, so exactly, that as can be seen on the crown of the head and on the base, the old rough surface of the marble still appears. He has done this sort of thing in other works, such as the tomb of Pope Julius II with the statue which represents the Contemplative Life [Rachel]: and this represents one of the master-strokes on the part of those who are leaders in the art.298

Again, it is emphasized that David was produced from a single block without additions. The vestiges on the head were removed during a later restoration, but those by the feet remain.299 This is the earliest work of art for which there is a sixteenth-century remark about Michelangelo’s habit of installing them in an unfinished state, his open tribute to sculpture’s relationship with nature. It is telling that the comment was made during a discussion about the expertise needed to handle the material in question, the marble block. A willingness to exhibit uncompleted sculptures was a fundamental quality of his art, and had partly to do with the prevailing idea of sculpture’s immediate and prestigious origins in nature. This went further than Michelangelo himself, and should be seen as part of the general aesthetic climate of the Florentine Renaissance.