CHAPTER 12

Via negativa

Sculpture, more than any other work of art, displays the immediate origin of its own becoming; how the hand of the artist has processed the material in order to realize its innermost qualities and potentials. This idea surfaces again and again in Alberti’s, Vasari’s, and Michelangelo’s writings on art. And it is underscored in Michelangelo’s letter to Benedetto Varchi regarding a symposium held in 1549, at which the respective merits of painting and sculpture were debated. The letter is the single most important statement about his craft given by the artist. It is the one instance when he explicitly commented on it to an academic circle. It is not a secondary source, and it is not given within the metaphorical discourse of poetry.

The letter, however, is brief, and full of excuses and conventional politeness. In the short central passage, he first claims that painting is better the closer it is to relief, and a relief is worse the closer it is to painting, and then follows Michelangelo’s concise definition of the art of sculpture:

By sculpture I mean that which is fashioned by the effort of cutting away, that which is fashioned by the method of building up being like unto painting.300

With the phrase that the sculptor operates by taking away, Michelangelo is referring to the well-established metaphor, which would hardly have passed unnoticed by Varchi and his academic colleagues.

In relation to Alberti and Vasari, however, it is telling that Michelangelo stressed the process of making sculptures more than the final result or the completion of an idea. Artistic work is first and foremost related to the block of stone, not to well-polished ideals. What is important is the effort, the craft of cutting away.

The reference was not limited to contemporary art critics though; it had much wider philosophical and theological implications. First, there was a clear connection with Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism.301 Then, there was the less acknowledged importance of a particular phrase in the theology and writings of the Christian–Platonic school—via negativa.

In the second part of the Parmenides, Plato addresses the problem of how to understand and describe the divine.302 A central issue is whether the divine should be understood as a single unity or as a conglomeration of several parts. The answer is that God is both one and several, so that he can appear in many guises, but still remain unchanging and eternal. This idea is dwelt on in one of Michelangelo’s last poems, the unfinished Sonnet 273. God himself, he says, is the one who sets all in motion, but must always remain the same. Yet, he will not always show himself to us in the same way—‘Non sempre a no’ si mostra per un verso’. Instead, he will appear to one person in this form and to another person in that. This is an extraordinary figure of thought: the prime mover in all his eternal permanence, making himself appear now in one way, now in another through decisive turns and deliberate movements. It is reminiscent of the reclining, slowly turning figures of the Medici Chapel and their different viste (Fig. 7.10 & 7.11).

In a similar discussion in Plato’s Phaedrus, one finds the embryo of Michelangelo’s idea about sculpture: ‘Now each one chooses his love from the ranks of the beautiful according to his character, and he fashions him and adorns him like a statue, as though he were his god, to honour and worship him.’303 Plotinus uses the same metaphor in the chapter in the Enneads on the beautiful. To begin with, he states that beauty is most of all encountered by sight, but that it may also be found in words and in music. Even the intellect can be beautiful, he continues, and then there is the beauty of virtue. Bodies are sometimes beautiful and sometimes not, but when we see the beauty of bodies we should not run after them, but ‘know that they are images, traces, shadows, and hurry away to that which they image’.304 With direct reference to Plato, the reader is exhorted to

go back into yourself and look; and if you do not yet see yourself beautiful, then just as someone making a statue which has to be beautiful cuts away here and polishes there and makes one part smooth and clears another till he has given his statue a beautiful face, so you too must cut away excess and straighten the crooked and clear the dark and make it bright, and never stop ‘working on your statue’ till the divine glory of virtue shines out on you, till you see ‘self-mastery enthroned upon its holy seat’.305

In the classical Platonic and Neoplatonic contexts, the sculpture metaphor was used to illustrate the purification of the soul, how philosophy will do away with the material world, and how thought will become ever more abstract; what is important is to rid oneself of the superfluous, to refine and to polish the surface.

Among Christian thinkers the trope was used in a somewhat different sense. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite was the author of the brief, concise, and much read Theologica Mystica. The treatise begins with a prayer to the Holy Trinity, leading us beyond unknowing and light to ‘the brilliant darkness of a hidden silence’.306 Then follow some reflections on the revelations of St Bartholomew and Moses, stressing that they could never really have seen God—for he cannot be looked upon—but only the symbolical expressions of his divinity. There are holy places, it is argued, but these are sites of Darkness rather than Perfection:

I pray we could come to this darkness so far above light! If only we lacked sight and knowledge so as to see, so as to know, unseeing and unknowing, that which lies beyond all vision and knowledge. For this would be really to see and to know: to praise the Transcendent One in a transcending way, namely through the denial of all beings. We would be like sculptors who set out to carve a statue. They remove every obstacle to the pure view of the hidden image, and simply by this act of clearing aside [aphairesis] they show up the beauty which is hidden.307

As with Michelangelo, it is the process that is emphasized, the clearing aside. The Greek term aphairesis means to take away or remove, and is a central concept of via negativa.308 Immediately after this paragraph follows Dionysius’ important distinction between the negative method and the affirmative one; the former beginning with the particular and ascending to the universal, the latter beginning with the universal and descending to the particular. The advantage of the former method is that it begins with what is already at hand. Only then does it move on to deny all materialism until the ultimate Darkness and Unknowing is within reach. The goal is humility before the world and before God, limiting both intellect and speech to a minimum. Finally, the idea of Divine Darkness is given its explanation within the tradition of via negativa. Since God is neither light nor darkness, it is better to begin with the negative and the well known: the dark. Only from there can one begin to work towards true knowledge of the divine.

An important shift of focus in the use of the sculpture metaphor thus takes place. While the ancient philosophers stressed the importance of refining the sculpture, the Christian philosopher focuses all attention on its origin in the natural world: the act of setting out to carve a stone becomes as important as the possible result. Since the Incarnation, wisdom is no longer to be found solely in abstract thinking, but just as much in meditating on the sufferings of Christ—on the divine as sited in the midst of human worldliness and cruelty. In another of his texts, The Celestial Hierarchies, Pseudo-Dionysius even approved of the idea of representing God as a worm, in order to ‘honour the dissimilar shape so that all those with a real wish to see the sacred imagery may not dwell on the types as true’.309

The mystical ideas and texts of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite were well known among Renaissance humanists and helped to form the Neoplatonic movement, influencing writers such as Nicolaus Cusanos, Marsilio Ficino, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.310 Special reverence was given to Pseudo-Dionysius by the Renaissance Neoplatonists, because it was thought that he was the Dionysius from Athens mentioned by St Paul as having converted to Christianity following the sermon on the Areopagus (Acts 17:34). This gave him a unique authority, being supposedly closer in both time and place to Christ and to Plato than any other known thinker. His existence and mystical writings gave credence to the idea of forging Platonism and Christianity. Dionysius, it was thought, was the secret source for the philosophers of late antiquity such as Plotinus and Proclus, rather then the other way around.311 Via negativa was often understood as an instrument for Platonic dialectics and as an important strategy in resolving the problem of idolatry.312 Nicolaus Cusanos devoted a whole chapter of his major work, De Docta Ignorantia of 1440, to negative theology. It is truer, he explained, ‘to deny that God is a stone than to deny that He is a life of intelligence’.313 Negation of the stone is fundamental and truthful, while describing God in the abstract displays the presumptuousness and hubris of the human intellect.

Ficino wrote a commentary on his translation from Greek into Latin of Pseudo-Dionysius’s works, begun in the early 1490s and published in 1496.314 He admired the ancient author immensely, categorizing him as ‘the culmination of the Platonic discipline and the column of Christian theology’.315 Within Colonna’s circle, the Areopagite was also influential and revered. Vittoria Colonna talks of him in a poem written for Michelangelo in c.1540, situating Pseudo-Dionysius alongside St Paul as one of the ‘great minds’ who had ‘captured the truth’.316

With all its mysticism, via negativa—giving credibility to an interest in the human and material world beyond the shrines—can be seen as part of a secular movement. ‘Everything’, stressed Pseudo-Dionysius, ‘can be a help to contemplation.’317 Seeking knowledge about the world may seem like a secular enterprise, but if even the lowest creatures are relevant for understanding God and his divine acts, these are holy matters as well. The secular became sacred instead of the other way around, as one recent scholar put it.318

There was an intriguing intersection of ideas about nature, philosophy, and theology in Michelangelo’s words about sculpture as the art of taking away, which must have appealed to him enough to use it in the letter to Varchi. It was the one argument he advanced in defence of his art, and it was one he felt would attract the attention and respect of the academic readers of his letter.

Perhaps Michelangelo took the arguments of Pseudo-Dionysius more to heart than just in his choice of phrasing. Neoplatonism has been evoked many times to explain Michelangelo’s art, sometimes successfully, but just as often in vain. Even though there is a clear historical relationship and an artistic affinity, Michelangelo’s art just does not seem abstract enough; it has an earthbound, chthonic quality to it that does not sit well with the general ideas of Platonism. The term is probably better reserved for the ideal art of the likes of Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and perhaps Raphael, even though many of their figures are also inhabited with far too much ‘immediacy and vitality’ to deserve such a label.319 Michelangelo’s figures are powerful, heavy, and seldom beautiful in a conventional sense. Their gestures are often tortured, their minds seem to be occupied by grief rather than enlightenment. They are figures of darkness and confusion rather than clear light.

It has often been noted that there is a strong tendency to melancholy, a sort of ‘natural negativity’, in much of Michelangelo’s art and writings. The letters are so preoccupied by worries that they would strike any reader as unusually dark and pessimistic.320 The happy notes are few: some good pears, cheese, and wine from his native Tuscany, or the wedding and children of his nephew.321 In October 1512 Michelangelo wrote to his father:

I lead a miserable existence and reck’ not of life nor honour—that is of this world; I live worried by stupendous labours and beset by a thousand anxieties. And thus I have lived for some fifteen years now and never an hour’s happiness have I had, and all this have I done in order to help you, though you have never either recognized or believed it—God forgive us all.322

Even the rare glimpses of humour were phrased in the negative. Writing for a favour, he commented that his patron might think that the favour would be thrown away on a man like himself, but ‘that one might still find some pleasure in granting favour to fools, just as one does in onions as a change of diet, when one has a surfeit with capons’.323 When it was suggested he build a colossal statue of the Pope, he replied by exaggerating the idea until it was grotesque, remaking the sculpture as a bakery with smoke coming out of its ears and with ‘bells charging inside and the sound issuing from the mouth’ so that ‘the said colossus would seem to be crying out loud for mercy’.324

In the very last and bitter letter to his father, Michelangelo sarcastically painted a dark picture of himself stealing money from his father and slandering him, obviously to make clear how he felt his father had acted against him. Painting everything as dark as possible came naturally to Michelangelo, and he often described himself as a melancholic, both in his poetry and in correspondence. In Raphael’s portrait, he is represented in the throes of a weary obsession with the material world, dark thoughts negating the stone (Fig. 6.1). In a letter of 1525, Michelangelo was pleased that an entertaining dinner has lifted him a little out of his melancholy and depression.325 At other times he embraced the mood as his only true joy—‘La mia allegrez’ è la maninconia’.326 From Herman Grimm onwards, modern critics have seen melancholy as one of the most important characteristics of the artist’s personality.327 It should be seen, however, as something more than a dark mood that the artist would often find himself in. At the same time it was a well-wrought intellectual, literary, and rhetorical strategy.

The most important question is whether these ideas meant something for Michelangelo’s artistic work and credo. Pseudo-Dionysius and the school of via negativa are, perhaps surprisingly, positive about artists and their use of ‘poetic imagery … not for the sake of art, but as a concession to the nature of our mind’.328 The best artists are godlike, imitating Christ in life and in their actions, and they ‘yearn only for what is truly beautiful and right and not for empty appearance’.329 This is a common Neoplatonic idea, of course, but for Michelangelo it may have been important to find it in a nominally early Christian thinker and in such a deeply religious context. His art, like via negativa, rejects abstract and complex meanings. Instead it embraces the natural (and just as much real as mystical) world of materiality, disclosure, and darkness.

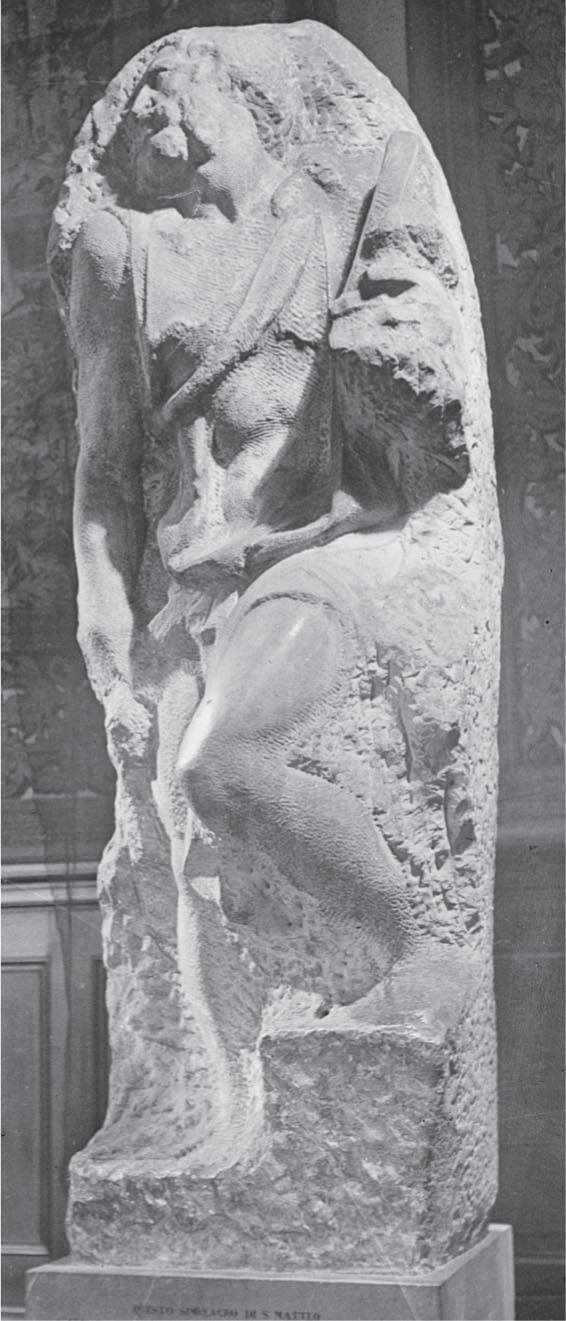

Fig. 12.1 Michelangelo, Saint Matthew, 1504–1508. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Marble. (Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

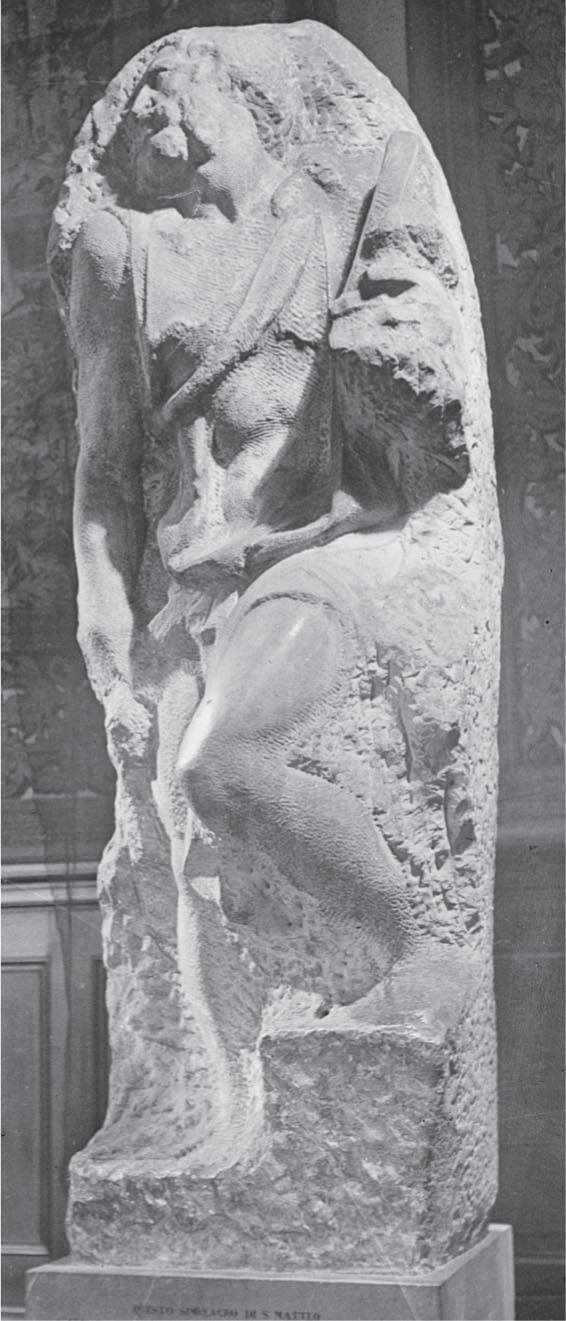

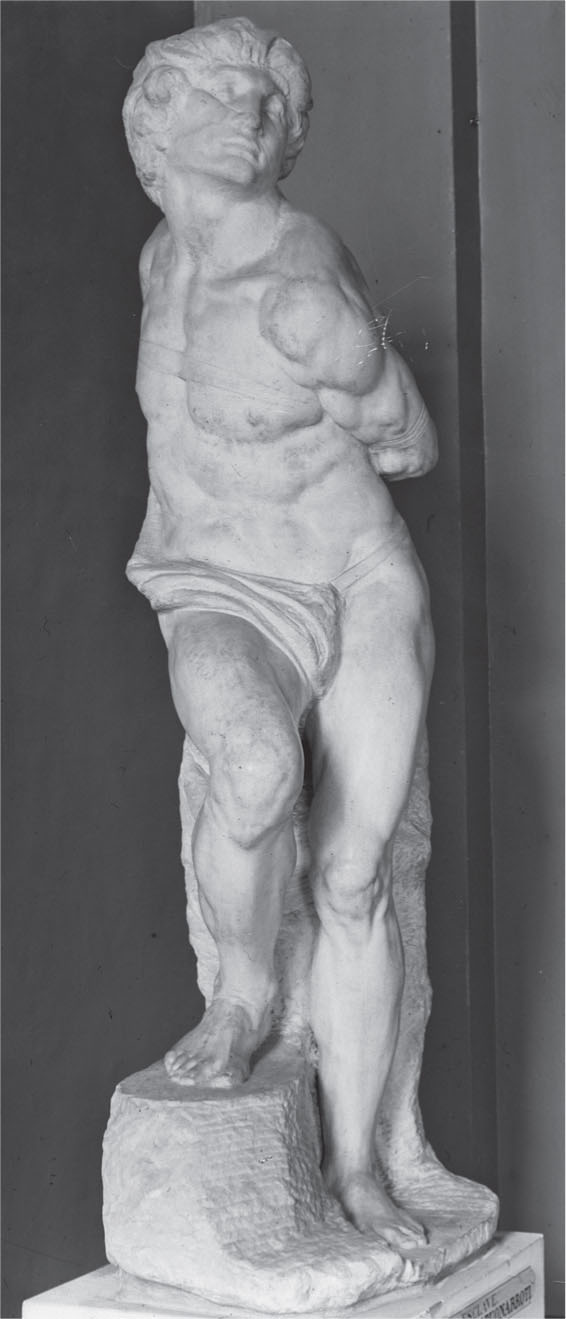

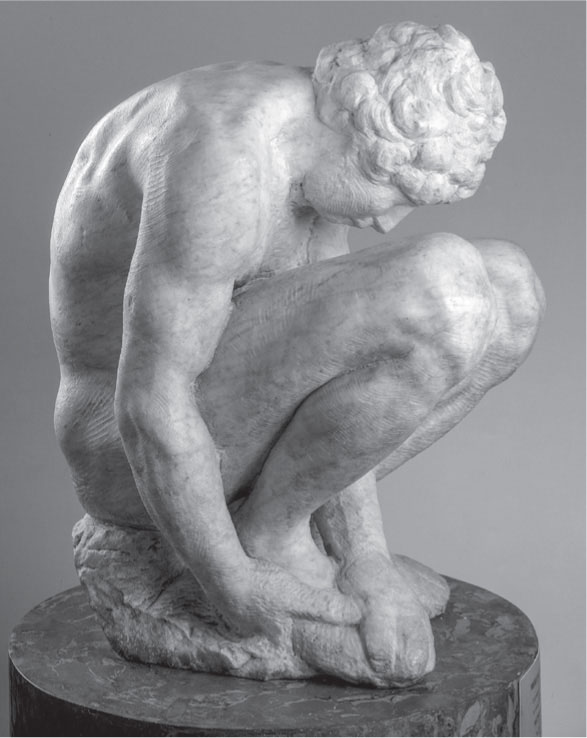

The information given by Condivi that the artist, as a sign of his mastery, would leave part of his sculptures untouched or at least unpolished is borne out elsewhere in Michelangelo’s work, such as in the early attempts to make sculptures look antique and in the Pietà for St Peter’s. Later in his career the artist was in the habit of leaving works altogether unfinished, the so-called non finito works.330 The earliest certain case was St Matthew, one of twelve marble Apostles planned for Florence cathedral (Fig. 12.1). Then followed the Slaves, the Atlas Slave, and the figure of a crouching boy begun for the tomb of Julius II but never used in the completed monument (Fig. 12.2 & 12.3). The Medici Chapel also contains figures that seem uncompleted, such as Darkness and the Madonna (Fig. 7.4 & 7.6).

Fig. 12.2 Michelangelo, Rebellious Slave, c.1514. The Louvre, Paris. Marble. (Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

Instead of reaching for the abstract and perfection, these works seem content to remain with the given chora, within the block of marble. They point to the process of becoming rather than to an ideal existence, and they mark out a direction instead of locating a specific goal. What is extraordinary is not that works of art were left unfinished—that happened all the time—but the extent to which they were already revered in the sixteenth century. Michelangelo himself, who systematically destroyed his own drawings, saw to it that the unfinished sculptures came into appreciative hands. Both Vasari and Condivi praised them, the former writing about one of the sculptures of the Medici Chapel that ‘with all its imperfections there may be recognized in it the full perfection of the work’.331

Fig. 12.3 Michelangelo, Crouching Boy, c.1530. The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg. Marble. (Photo: Alinari Archives)

Their particular kind of expressiveness seems to have attracted both artists and critics, while the classicism of subsequent centuries never tolerated another legacy of works such as the Michelangelo non finiti. The ideas of via negativa may have helped in this preference for the unfinished, stressing the importance of beginning with natural thinking, with the givenness of Being, in order to be able to move towards the ideal. Similar to dialectics, via negativa was a method rather than an ideology, a way of dealing with the world and of becoming rather than simply being. It brought to Platonic idealism and Christian theology a healthy and profound scepticism towards ideals of perfection and unblemished beauty. To use the most famous of the Platonic metaphors, it did not see the dark cave as something that should merely be abandoned and forgotten. The cave, like the forge, was an essential underground site for true understanding—for philosopher and artist alike.