CHAPTER 13

The late pietàs

In the 1550s Michelangelo, seemingly without having any commission to do so, produced three large-scale sculptures on the pietà theme.

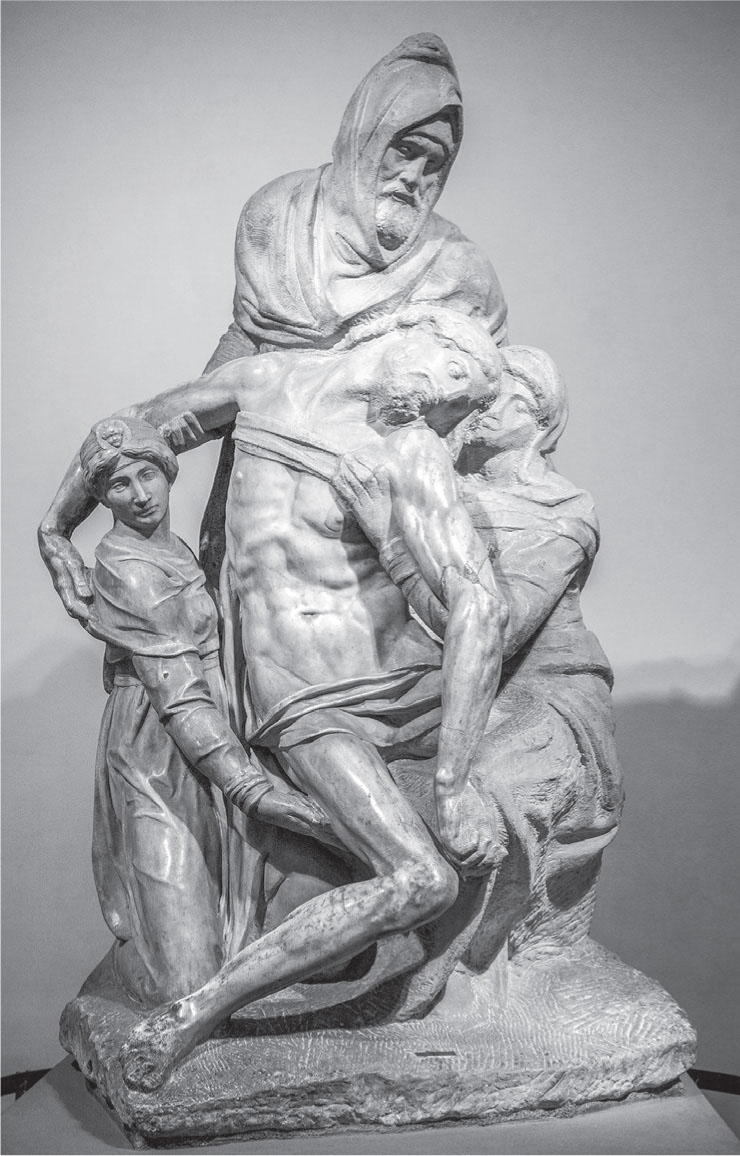

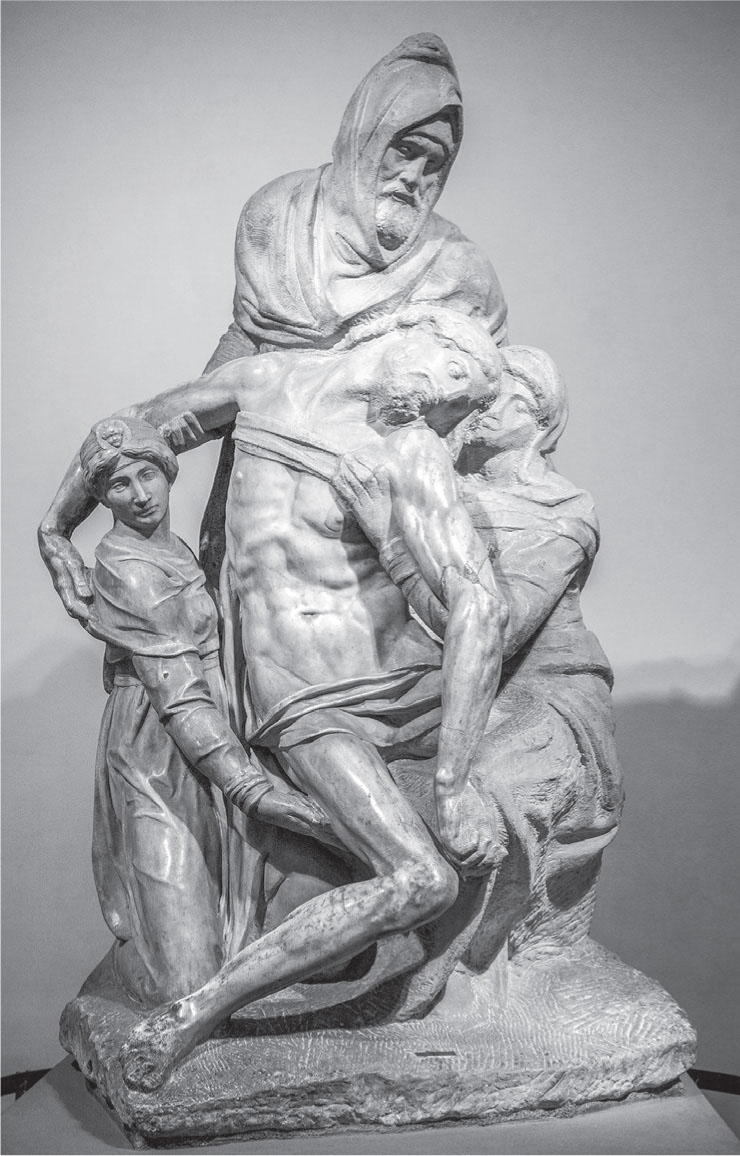

Best known is the one now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence (Fig. 13.1).332 There are important differences from the early pietà in Rome (Fig. 4.1): the Florence group consists of four figures instead of two; the body of Christ is not lying in the Madonna’s lap, but is being lifted by those present; and the figures are altogether disproportional, lacking any natural viewpoint or prospect. The focus is even more on the displaying of Christ’s body than in the early version, yet no one has the power of demonstration here, making the work both more disparate and more unified. Vasari tells us that Michelangelo at some point considered the sculpture for his own tomb, but that he gave up on the work, began to destroy it, and ended up giving it to the Roman banker Francesco Bandini.333 Despite thorough research, much is still unclear regarding the precise motif, the function, and the original or intended installation.334 Though probably intended for a church altar, it wound up instead in the garden of the Villa Bandini on the Quirinale in Rome—together with a collection of more than thirty ancient sculptures and fragments. It has been suggested that the setting was designed by Michelangelo himself, but this is uncertain.335 True or not, in a print from about 1580 by Cherubino Alberti the sculpture is placed in a sacred landscape, indicating how it was displayed in the sixteenth century and in stark contrast to the museum environment where it is seen today (Fig. 13.2).

A second unfinished work, the Palestrina Pietà, was found in the early twentieth century by Albert Grenier.336 The often-disputed group consists of three figures and is even less complete than the earlier version. Only the front torso and the upward-pointing hand of the rear figure seem to be finished.

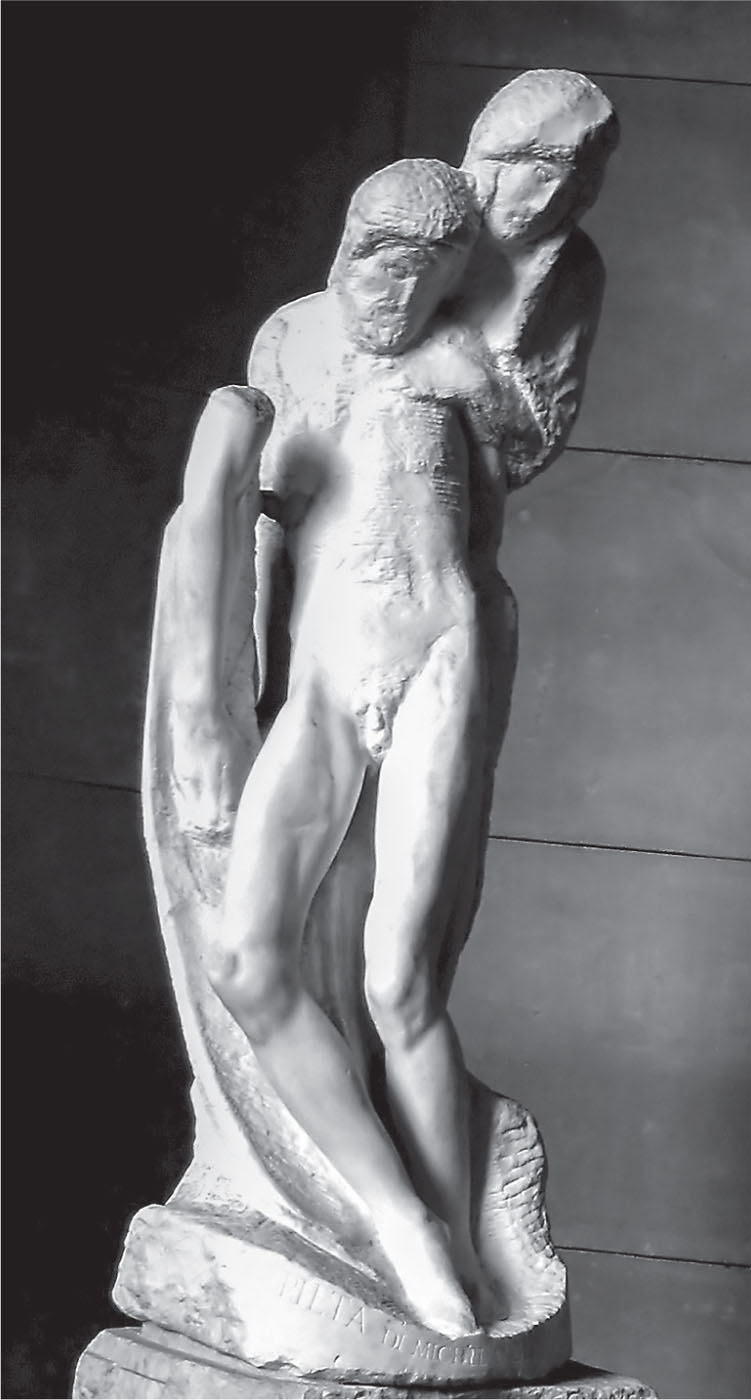

A third unfinished pieta, the Pietà Rondanini, was found in Michelangelo’s studio after his death (Fig. 13.3).337 The group is now reduced to two figures, like the early Roman Pietà—only Mother and Son remain. It seems as if Michelangelo, after many years of labouring on the theme of masculine strength and potency, had found the ultimate path to simplicity and radical reduction. Even more than its predecessors, this work seems beyond completion; it is not only incomplete, it is distinctly non-completable. Most disturbing is the well-polished arm protruding from the block to the left of Christ. Connecting this limb with any of the two figures must have been impossible.

Fig. 13.1 Michelangelo, Pietà, 1550s. Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence. Marble. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

The Pietà in Florence is unique, in that Michelangelo has carved four integrated figures from one marble block, a restriction that was not imposed by circumstance or patron this time, but was purely the artist’s choice. A link with the Laocoön Group has been assumed—though that work was not actually carved out of a single block (Fig. 3.1).338 There is also a relationship with the Easter Sepulchre tradition, with its unique constructions of complex relations between full-scale, three- dimensional figural units and an emphasis on the effect of the whole rather than the individual figure (Fig. 4.2). The late pietàs can be positioned between Niccolo dell’Arca’s expressive, relational terracotta sculptures and the more sustained idiom of the marble Laocoön. The most obvious thetic force, though, is the artist’s own early Pietà in Rome. It is as if the artist had remembered that he signed that work, probably under the influence of Poliziano and classical sources, as if it were still awaiting completion:

Fig. 13.2 Cherubino Alberti, Michelangelo’s Pietà, c.1550. Engraving. (Photo: British Museum)

Fig. 13.3 Michelangelo, Pietà Rondanini, 1560s. Castello Sforzesco, Milan. Marble. (Photo: Shutterstock)

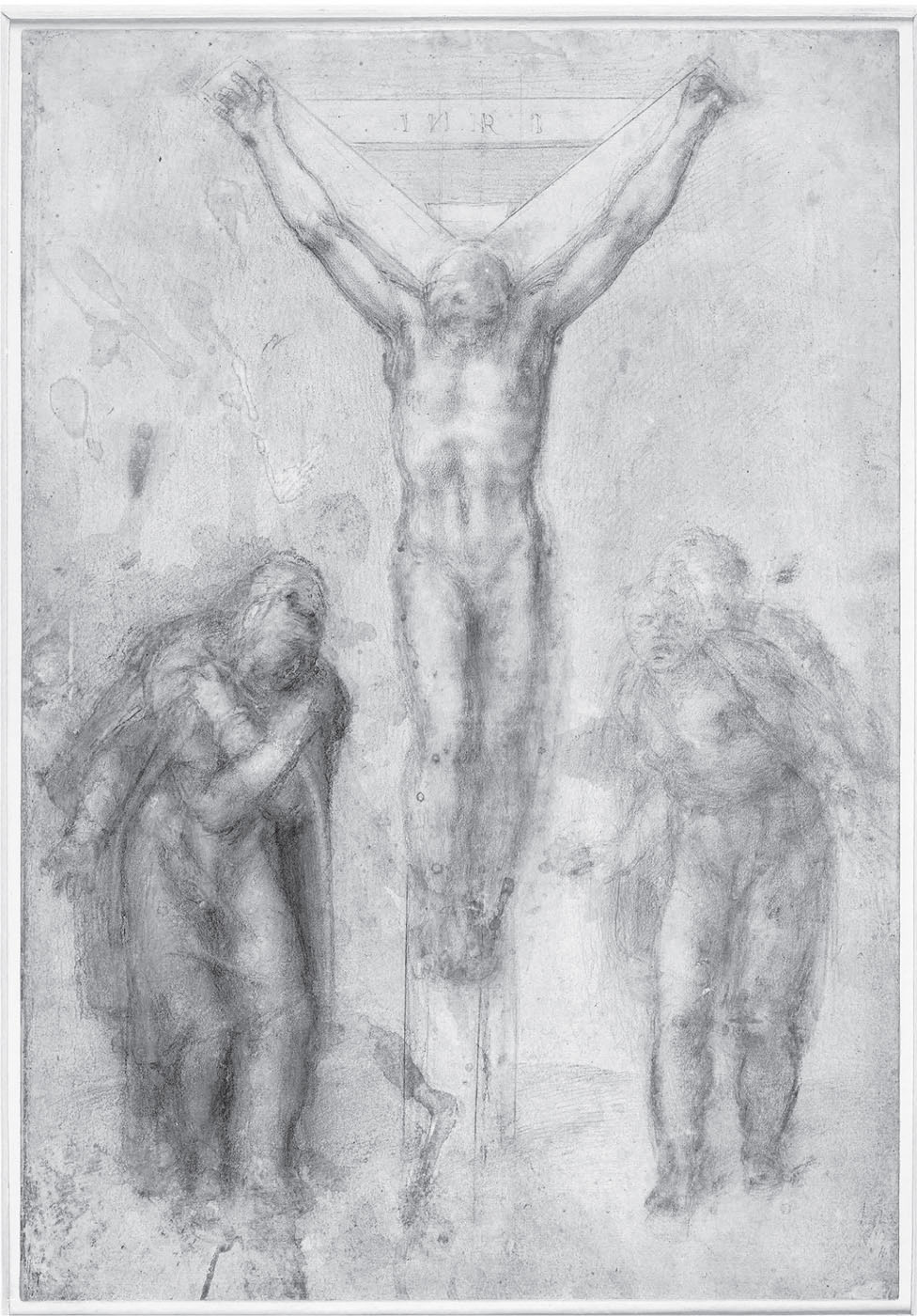

Fig. 13.4 Michelangelo, The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John, 1562–1564. The British Museum, London. Black chalk drawing with white highlights. (Photo: British Museum)

MICHAEL.ANGELUS.BONAROTUS.FLORENT.FACIEBA[T].339

Fifty years later he decided to pick up his hammer and chisel again, to continue the process. Over 70 years old, Michelangelo himself had become an authority and example to follow. His works were hailed by Vasari and others as a light in the darkness for all artists:

Oh, truly happy age of ours, and truly blessed craftsmen! Well may you be called so, seeing that in our time you have been able to illumine anew in such a fount of light the darkened sight of your eyes, and to see all that was difficult made smooth by a master so marvellous and so unrivalled! … Thank heaven, therefore, for this, and strive to imitate Michelangelo in everything.340

Never content with imitation, Michelangelo instead had to emulate himself, just as he had always struggled with his contemporaries, predecessors, and younger generations of artists. After the youthful success of abstract beautification, the remaining territory to explore was a negative one—the discourse of disorderliness and darkness (Fig. 13.4). As in the uncompleted sculptures, so in many of the late drawings: the same aesthetic prevails.341 Unfinished instead of complete, with the fragment as its most expressive device, these are works of art that live up to Walter Benjamin’s high ideals of aesthetic perfection: ‘Others may shine resplendently as on the first day; this form preserves the image of beauty to the very last.’342

In terms of soundscapes, the early Pietà in Rome represents weeping, tears rolling softly down the Madonna’s cheek, while the later pietàs are more unsynchronized, avant-garde trios, duets, or solos of a deep, dark, and previously unheard-of timbre. The homelessness of these sculptures—finding a place wherever they have happened to be sited—added to their tragic appearance. Unfinished as they are, they appear abandoned, non-sited.