CHAPTER 15

The Last Judgement

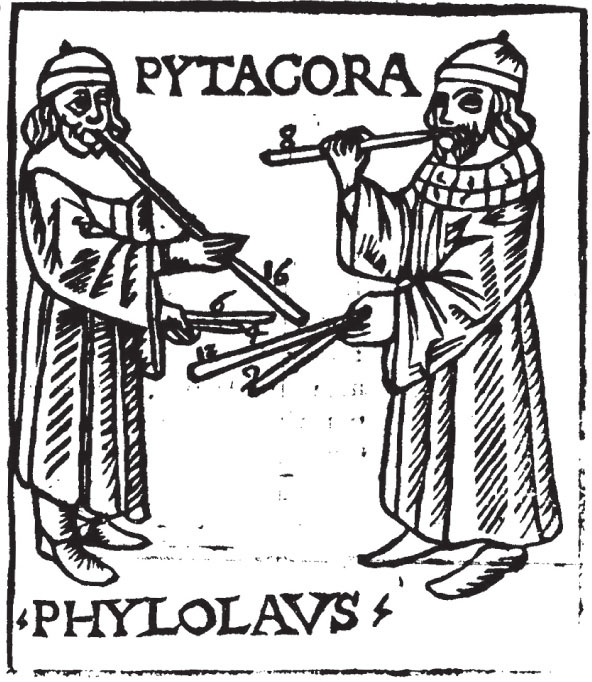

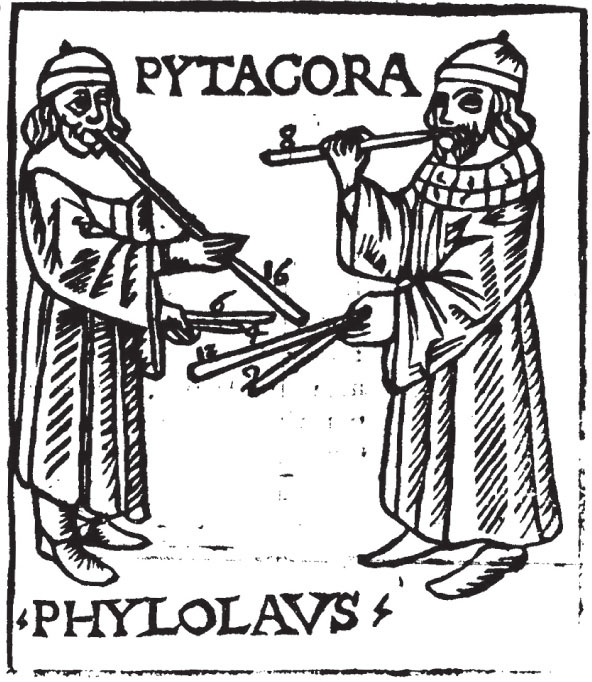

The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel is the concluding statement and climax of Michelangelo’s biblical history. This is where the world of mankind comes to an end (Fig. 1.1). Even by Michelangelo’s standards the fresco, at almost 200 square metres and with more than 300 figures, is simply overwhelming. From the grandiose design and possible artistic intentions, down to the singular figures and their expressive gestures, it has always awoken amazement, frustration, and debate.351 The work is a hurricane of terrible sounds, never before heard. All the four elements participate in the orchestration: the earth giving back its dead, water flowing in the river of Acheron, unruly winds catching at the figures, and the fires burning in hell. People cling anxiously to one another, falling, fighting, and struggling desperately; heavy bodies collide. Even the dead are screaming as they rise from their graves. The figures surrounding Christ are pleading loudly, while the protagonist himself appears as a flash of intense lightning and thunder. Below him angels trumpet insistently, adding to the welling sound of moans, complaints, and fighting figures. The angel’s trumpets relate to the Pythagorean system. According to myth, the philosopher became aware of the abstract orderliness of musical intervals when watching smiths at work in a forge. The story is illustrated by a woodcut in Franchino Gaffurio’s Theorica Musicae of 1492 (Fig. 15.1). The first image shows the smiths at work; the second, Pythagoras himself playing different instruments, concluding with pipes, marked as ‘16’ and ‘8’ long (the ratio for an octave being 2:1 for pipe lengths). In Michelangelo’s painting, the trumpets with their fixed lengths represent an orderly and well-tuned soundscape. The longer horns are echoed visually by Charon’s oar, beating off the travellers in his little bark. Only the Madonna seeks to withdraw from the turmoil, silently protracting her body and covering her ears.352 This scene is in many respects better read as a soundscape than as a text: a soundscape is more coherent and pays greater justice to its visual expressiveness than a purely iconographical interpretation can do.

Fig. 15.1 Unknown artist, Pythagoras discovering and demonstrating the relation between musical intervals. From Theorica musicae by Franchino Gaffurio, Milan 1492. Woodcut. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The first mention of Michelangelo painting the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel was in 1533, when the artist was almost 60 years old and already a living legend. Actual work on the fresco began in the spring of 1535 with the technical preparations, and Vasari mentioned that the whole altar wall was torn down and rebuilt to make sure it would ‘overhang about half a braccio from above so that neither dust nor any other dirt might be able to settle upon it’.353 The project meant the destruction of two original paintings on the wall from the 1480s, several portraits of popes above them, and even of some of Michelangelo’s own work done in conjunction with the painting of the ceiling about thirty years before. The artist completed the project of the gigantic fresco in the autumn of 1541. Besides its multitude of figures and colossal format, The Last Judgement displays a number of remarkable features. One is the central importance of the Passion. Christ is represented with his five wounds and the symbols of his suffering, above all the Cross and the Column. Another characteristic is the highly untraditional composition, lacking any kind of border or frame, and without any clear structure or rendering of space. At first glance the painting seems to be void of compositional structure altogether; the many figures appear to float about in space, against the deep blue background. The background itself is not unimportant, though, being executed with an astonishing quantity of the expensive ultramarine pigment.354 The composition also has none of the usual clear distinctions between the blessed and the damned. Instead, it can better be divided into three zones, with the symbols of the Passion at the top (the Cross and the Column), the return of Christ in the middle, and, below, the dead rising from the grave and the crossing of the river of Death. A last puzzling detail is the small grotto immediately above the altar, which is wholly absent from comparable accounts of the motif (Fig. 16.4).355

Central to most iconographical interpretations of The Last Judgement is the symbolism of light. According to Charles de Tolnay, the magnificent blue background should be understood as ‘the limitless space of the universe’, and he points to the fact that there is no unifying source of light within the composition.356 Christ himself is understood as the centre of an artistically created cosmos. ‘Christ is here the centre of a solar system: around him revolve all the constellations of the universe.’357 He is compared to Apollo, because of the surrounding light, his beardless face, and classical profile—not unlike that of Apollo di Belvedere. Tolnay also makes several connections with light symbolism in the Bible. St John says, for example, ‘this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil’ (St John 3:19). In the Gospel of St Matthew, Jesus himself prophesied the Last Judgement in terms of light and darkness:

Immediately after the tribulation of those days shall the sun be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light, and the stars shall fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens shall be shaken: and then shall appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven: and then shall all the tribes of the earth mourn, and they shall see the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven with power and great glory. (Matthew 24:29–30)

Tolnay also made a comparison between Michelangelo’s art and worldview and Copernicus’ and Giordano Bruno’s revolutionary ideas about the order of the universe. In Tolnay’s interpretation, Michelangelo’s Last Judgement represents a heliocentric universe. Its ambition is to disturb and question—rather than simply draw on—the ideals of the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Counter-Reformation. The artist appears as a visionary spokesman for the scientific revolution, a rebel against traditional authority, and, one might almost say, an avant-garde artist.358 The small, threatening cave above the altar poses some problems to this interpretation, but Tolnay is inclined to believe that it represents Limbo (the place where those unfortunates who lived before the time of Christ await the end of time) rather than Hell.359

Leo Steinberg has discussed the same iconographical problems in greater detail. He is puzzled by the fact that it is not Hell that is depicted in the lower right-hand corner, only its entrance. He also shows that the grotto above the altar canot be Limbo, since the flames do not correspond with accepted doctrine about the place. Neither does he approve of the idea that it represents purgatory, as he shows that purgatory was a topic of great dispute among leading Catholics at the time and was seen by many as mere superstition. Instead, he suggests that Michelangelo promoted a ‘Merciful Heresy’, an artistic questioning of the whole idea of Hell as a place of eternal suffering.360 It is questionable whether this forbidding painting really does have such a positive and optimistic message. There is a clear light surrounding Christ, but otherwise the rest is darkness. The total absence of Paradise is what is really unconventional in this Last Judgement. There is not a hint of it anywhere, and instead most of its lower part is occupied by a gloomy description of Hell. If there is an optimistic note, it is perhaps best found in the theology of via negativa and the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who claimed that one should start the search for salvation in the darkest regions, where one is bound to find that Evil has no true existence of its own, but is only a momentary departure from Good. Just as Christ in Michelangelo’s fresco dominates the scene completely, goodness extends and reaches out everywhere: ‘Some share completely in the Good, others participate in it more or less, others have a slight portion only, and to others, again, the Good is but a far-off echo.’361 In the painting, all figures seem to be striving to imitate or conform with the Christ figure.362 According to Pseudo-Dionysius, there is no source and no purpose behind Evil—and that is part of its triviality. Interestingly, the philosopher did not attribute Evil to the body; Evil does not require a body, he says, but is rather to be understood as a weakness of the soul.363

A problem with many interpretations of the fresco is that Dante, even when his importance is recognized, is relegated to the background. According to contemporary sources Michelangelo was a great admirer of the poet, and would even quote long passages from memory.364 That the literary source for the lower part of The Last Judgement is Dante’s Inferno is undisputed, and one of the most original aspects of the Sistine painting. Not only does it introduce a profane writer among the canonical texts, it also sites a pagan myth together with the biblical motifs. In the third canto of Inferno, the protagonist passes through the gate of Hell with its inscription ending with the words ABANDON ALL HOPE, YE THAT ENTER HERE.

There sighs, lamentations and loud wailings resounded through the starless air, so that first it made me weep; strange tongues, horrible language, words of pain, tones of anger, voices loud and hoarse, and with these the sound of hands, made a tumult which is whirling always through the air forever dark, as sand eddies in a whirlwind.365

The soundscape is very much the same in Dante’s text as in Michelangelo’s painting, and the protagonist’s companion Virgil explains that those found in that region are those who, ‘lived without disgrace and without praise’. After a while they meet the ferryman Charon, transporting the souls over the river of Acheron. Charon has eyes like burning charcoal and hits those who lag behind with his oar, just like in the painting. On the other side of the river awaits the tooth-grinding Minos. According to legend this is a portrait of the Papal Master of Ceremonies in Michelangelo’s time, Biagio Martinelli da Cesena (1463–1544). Vasari said that he railed against the fresco and the portrait was supposedly Michelangelo’s revenge. The Pope sided with the artist in the conflict, replying to Martinelli’s complaints that he had no influence over the region of Hell, and therefore could do nothing.366

A reading of Dante makes it clear that what is depicted in the fresco is without doubt Hell—its vestibule so to speak. The river Acheron is clearly said to be situated in Hell and it does not divide the blessed from the damned. That there are several caves in Hell is not surprising. The word inferno itself could be translated into hole, just as well as hell, and in most early representations there are caves and grottoes aplenty in its landscape. The iconographic investigations point to the importance of the Passion and the symbolism of light in the fresco. However, there is little agreement as to why these themes became so important in the Sistine version. One possibility is that the site, the rituals to be held there, and the conditions of spectatorship exercised a fundamental influence on the iconography.

A key witness, of course, is Gunnar Wennerberg, and the keen account given in his poem Allegri’s Miserere, written after visiting the Sistine Chapel at Easter 1852. It is worth quoting the poem in translation in full:367

Now I have heard Allegri’s Miserere.

And I’m alive, not altogether extinguished.

In the surge of aesthetic excitement,

If for a moment—it is to be pardoned –

Spirited away by its mighty waves

I lost my senses.

It was the fifth day

Of the holy week, four o’clock.

In the chapel, the Sistine, prevailed,

A sense of solemnity. Close to the railing,

In a place that certainly evoked envy,

Stood I amongst strangers from all,

Almost all countries of Europe.

Above me I had Buonarroti’s

Mightiest creations—I mean

The vault with prophets and sibyls,

The cherubs of Jehovah made human

Around which evangelically lit

Child seraphs stand and cheerfully listen;

Right in front of me on the altar wall

Dark and horrible ‘Judicium extremum’

By the same Dante of the painters;

And to the right and the left other

Works by great men, small beside the Titan.

Above the altar and on the same

Burning candles of wax, but with pale flames,

‘Cause still the rays of the afternoon sun

Blazed the upper part of the chapel,

While in the lower part

The evening twilight spread its gloomy veil

Over the objects.

Here at the centre

The Pope was sitting on his throne, around him

Upon high benches sovereigns of the church

And below them, almost hidden away,

Lower dignitaries; all dressed

In accordance with rank and value, each in his way,

In splendid robes.

Long it was

Silent as in a grave. Finally though was heard

The choir to begin.

The text was from David’s

First Psalm of repentance taken, and the music –

If it so should be called—was an unpleasant

Harsh and dry recitative chanting,

Unison, only a few times qualified

By a triad. When now the Psalm was finished,

One of the lights was extinguished, and a silence

Broke in very briefly, a few minutes;

Then another Psalm began again,

Another text, but deliverance the same

As before; and now when it was ended,

The second light was put out. And so it continued

This strange spiritual exercise,

As tiresome for the soul as for the senses,

Until the twenty Psalms were sung,

And of the candles, twenty-one from the start,

Only one was left.

Was the ear,

During this long time of anguish

Tortured by an eternal monotony

This was not at all the case

However with the eye.

The shimmering afternoon sun

Had little by little fled the vault,

And the cherubs up there wrapped themselves

Into a threatening darkness. The place again

Closest to the altar was the only one,

Where things could be discerned

Despite a constantly dwindling light.

And when this finally consisted of

Only the last light of the last candle,

That with a gloomy flickering in a gingery flare

Only now and then was able to disperse

The shadows of darkness around the lower part

Of the pictured Doom—this horror,

Where an abyss, full of awfulness,

Opening its throat, and above these,

The damned, muddled together,

Agonized, turning around in futile attempts

Not to sink, while others

Already taken by the lockjaw of despair

Hopelessly staring down the gaps of hell,

Constantly drawn there by the gravity of sin—

And it seemed as if these masses

Were moving in the dusk up and down;

Oh, then I was struck by an unspeakable agony

And I turned my gaze from the sight.

Then, what rumble? Frightened I crumpled

As often happens, when a longer

Silence suddenly is broken. In the darkness

I hear more than I see, how all

Bishops, Patriarchs, Cardinals

Unanimously get up from their seats

And with the Pope ahead proceeds

Slowly forward, towards the altar round, falling

There on knees.

The last candle moved

Down from its place, but is not extinguished.

A minute of holy silence follows;

And, as a cry from the deep below raises,

Miserere.

Never shall I forget

This moment, so captivating and solemn,

I was ecstatic … beyond myself …

Yes, I was so; and then it is not asked:

Why? Now, when only memory

Pale, but unforgettable, stands me by

What before I have lived through, is tried

Many times what then was only felt.

So also

I do now, but perhaps unfairly.

Just like

Many an image, which has its value,

only at that place where first it was set

in the correct light by the master himself—

That is, not entirely on its own—

So too this Miserere.

Not by

Any high melodic beauty, not by

Any rich harmonic changes

And neither by any special

Peculiarity in rhythm is it

That its praise is justified; the more

By the moment, the atmosphere and manner,

Whereby these masses of tones,

Broad, drawn, obscurely into each other

Moving and mystically woven together

Powerfully swollen out and again dying away

Like the sound of an Aeolian harp,

Above which, like meteors

Suddenly shining in a starry space,

Moving in high, daring paths

Free voices, jingling and jarring

Of the wonderful kind I learned to

Know ‘ready before in Ara Coeli.368

I was ecstatic—it is already admitted –

And captivated, but not only by the song;

No, it was the whole, that enchanted

Eye, ear, fantasy and feeling.

It was beautiful, but not of the kind,

That its vitality eternally new-born gathers

From the kernel of its own sound truth;

It was beautiful, but like an Apple of Sodom,

Like a splendid pyromaniac fire in the night,

Grand, but without essence, a shallow seeming life.

–––

You Catholic, centuries-old church,

Who with the help of art’s lever,

Knows so well to lift, pull towards yourself,

Enchant and intoxicate young senses,

And the old lull to sleep and deaden;

It is time, for you in rags and ashes

Thinking of judicium extremum,

Let the lights burn, light some more

And sincerely sing miserere.

The question that must be asked is whether what Wennerberg saw was indeed the legacy of a Renaissance multimedia spectacle; if it is true that not only Allegri’s Miserere but also Michelangelo’s Last Judgement were produced with the described Easter ceremonies in mind.

The suggestive darkening of the chapel and the altar wall described by Wennerberg can have been nothing else but the age-old ritual of Tenebrae (Fig. 15.2).369 It goes back to ancient times and was celebrated by the Early Christians, perhaps even in the catacombs. Celebrated during Easter, its fundamental characteristic is the successive darkening of the ritual site. Usually there were twenty-four candles burning, representing the twelve Prophets and the twelve Apostles, extinguished one by one until complete darkness prevailed. Sometimes a final candle, representing Christ, was added. The noise Wennerberg heard when he turned away from the scene was not incidental, but the strepitus or ‘great noise’ associated with the Tenebrae, and supposed to keep the Devil at a distance.370 According to the Papal Master of Ceremonies, Johann Burchard, the Pope had begun to celebrate Tenebrae by 1484. The ritual was noted in his diary but with no information as to where it was held. It may well have been in the Sistine Chapel, come 1486 he noted it again, this time adding that it took place in Cappella majore, as the Sistine Chapel was also known. In 1487 his note is a little more extensive, giving us to believe that the ritual was largely the same as that described by Wennerberg.371 In 1538, when Michelangelo was already at work on the painting, there was a short note in Martinelli’s diary that Tenebrae was celebrated on three successive days during Easter, on Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, and Good Friday (15–18 April).372 The dramatic darkening was not only a widespread tradition in the Church.373 Leone di Sommi of Mantua wrote in c.1565 that he had used similar effects in secular theatre, creating ‘a profound impression of horror among the spectators’.374

Fig. 15.2 Michelangelo’s Last Judgement with arrangement of lights and lightholders during the celebration of Tenebrae in the Sistine Chapel. (Reconstruction: Petter Lönegård)

The use in the Sistine Chapel of twenty-one instead of twenty-four candles was the first compromise with tradition within the Papal walls, almost certainly done in order to adapt the rite to the singing of David’s Psalm 50, with its twenty-one verses. The first line has given the psalm its title: ‘Miserere mei, Deus’:

Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving kindness:

According unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions.

Wash me thoroughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin.

For I acknowledge my transgressions: and my sin is ever before me.

This is the voice of a sinful and regretful believer, repenting his sins and begging for forgiveness. It was much used and reflected on during the Renaissance—Savonarola meditated upon it in his last days in prison, for example,375 in a meditation that became one of his most famous works, beginning with the words:

Alas wretche that I am, comfortlesse, and forsaken of all men, which have offended both heaven and earth. Whither shall I go? Or whither shall I turne me? To whom shall I flee for succour? Who shall have pitie or compassion on me? Unto heaven dare I not lift up myne eyes, for I have greevously sinned against it, and in earth I finde no place of defence, for I have bene noysome unto it.376

The Miserere has also had a special attraction for composers and singers, being introduced in the Bible as a song by the Master of Music, the ‘victori canticum’. The most famous setting of the text—and today the most often performed—is the one by Gregorio Allegri (1582–1652), composed by the singer of the Sistine Chapel in the mid-seventeenth century.377 It consists of three parts that alternate: a somewhat abrupt recitative in a simple monotone; a choral part with sweeping, airy harmonies; and the final part with a lone soprano voice that reaches up to a high C. The piece became famous not only for its beauty, but also for what was understood as the great secrecy surrounding it. In Allegri’s time it was never written down, and the earliest manuscript is from 1661, nine years after the composer’s death. A century would elapse until the next notation, after which followed a number of manuscripts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They are all slightly different, primarily as regards ornamentation.378

For a long time only three copies of the piece existed outside the Vatican. Emperor Leopold I (1640–1745), who had a great interest in music, owned one, sent to him from Rome on request. When performed in Vienna, the Emperor found that it was not at all as beautiful as it was rumoured to be. He complained about the transcription to the Pope, who took the matter seriously and had his Master of Music removed. The latter countered that the beauty of the piece was wholly reliant on the special singing techniques and ornamentation developed among the Sistine Chapel singers. Their traditions could not be written down, and had to be communicated by careful schooling. The explanation was accepted and the Master of Music was reinstated.379 Other contemporary sources show that this unique performance practice embraced such unusual effects as voices fading in and out and slowing down towards the end of a piece.380 As musicologists have noted, even the ‘falschen Gesänge’ (false singing) was firmly established within this abstruse and singular choral tradition.381 Wennerberg, in his poem, described the music as ‘masses of tones’ that are ‘drawn, obscurely into each other, moving and mystically woven together, powerfully swollen out and again gone dying’. Above them, ‘like meteors, suddenly shining in a starry space, moving in high, daring paths’ were heard the sopranos’ ‘free voices, jingling and jarring’.382

The oldest of several Miserere in the Sistine Chapel tradition that has come down to us was composed by Costanzo Festa (c.1490–1545) in the time of Leo X.383 It was the first piece in the falsobordone style of recitation, and, similar to Allegri’s work was written for two choirs, alternating recitative with choral settings. Paris de Grassis, who replaced Johann Burchard as Master of Ceremonies in 1506, noted in 1514 that Tenebrae was celebrated during Easter and that he was most content with the singing of the Miserere, which was altogether devout and beautiful.384 In 1518 he made a note of the same event, but this time he was very critical: ‘At the end of the Office I was not pleased. The singers sang the Miserere mei Psalm as a falsobordone, which is what the Pope wanted.’385 The year before, Costanzo Festa was recorded as a singer in the chapel for the first time, and it seems possible that he was the composer of the first Miserere in the new style.386 A likely candidate for this piece is a Miserere kept in the Vatican, which has an old attribution to the composer.387

Little is known about Festa’s background, but he was probably from a family of musicians.388 He was born in Italy but spent his early career in France, earning him a mention by François Rabelais in the prologue to the fourth book of Gargantua and Pantagruel.389 Festa’s first known piece is a motet on the occasion of Anne of Brittany’s death in 1514. He then spent three years moving around in Italy, finally settling for good in Rome. Although today best known for his madrigals and the remarkable 125 variations on the tune La Spagna (sometimes mentioned as a forerunner to Johan Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations, but being variations of timbre, rather than melody), it was for the Papal Choir that he produced most of his works, and he was perhaps the single most important influence on Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.390 His motet Lumen ad revelationem gentium is interesting in the present context, since it was written for a very specific liturgical event: the distribution of the Easter candles by the Pope.391 Another of Festa’s compositions, the Te Deum, was still sung at the installation of new Popes and Cardinals in the nineteenth century.392 Just like the Miserere, these two pieces were composed to reinforce traditional rituals by adding extraliturgical, aesthetic elements. Together with such motets as Florentia, Tempus est poenitentiae, and Jesu Nazarene, they are also good examples of the particular robustness of Festa’s style. Traditional chanting is contrasted with more elaborate ornamentation and a wide range of voices, enabling the melody and rhythm to emerge more clearly than in works by, say, Josquin des Prez or Palestrina, who are much more elaborate and serene. Festa’s motet Quam pulchra es amica mea was praised by Charles Burney in 1773 as ‘a model of elegance, simplicity, and pure harmony … as if it was a product of the present century’.393 With a straightforward approach that does not shun disturbing clashes or contrasts and his fondness for tight clusters of voices or figures, there is indeed a similarity of style between Costanzo Festa’s music and Michelangelo’s art.

Fig. 15.3 Marcello Venusti, Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, 1549. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. Tempera on panel. (Photo: Alamy Stock Photo)

It may be difficult to appreciate how radical and expressive Festa’s Miserere seemed when first heard in the early sixteenth century. The falsobordone style is characterized by tight settings for voices, closely following the text in rhythm. The voices follow one another at the same interval, so that they move in similar patterns of thirds and fifths. A British writer of the eighteenth century heard a hymn to Maria sung by Sicilian boatmen in the falsobordone style and described it lyrically:

The music was simple, solemn and melancholy, and in perfect harmony with the scene, and with all our feelings. They beat exact time with their oars, and observed the harmony and the cadence with the utmost precision. We listened with infinite pleasure to this melancholy concert, and felt the vanity of operas and oratorios.394

Whether the falsobordone style originated in church or folk music is irrelevant here.395 It was more important that a listener such as Paris de Grassis was struck by its clear and deliberate expressiveness, finding it unworthy of the solemn occasion. Presumably the Master of Ceremonies thought the unusual, sensual music was a distraction from the ceremony itself, a complaint that has often been made against the use of music and art in Church, not least in the sixteenth century. It was heard again when Paris de Grassis’ successor Biago Martinelli da Cesena attacked Michelangelo’s Last Judgement for going beyond the bounds of decorum.

The new intimacy between ritual and music, the refined aestheticism introduced by Festa, was thus at first unfavourably received by the Master of Ceremonies, but approved of by the Pope. Soon it became not only an accepted but also popular part of the Easter celebrations. This may well have encouraged Michelangelo to achieve something similar in painting when he in 1535 received the commission by the Pope to paint The Last Judgement. Moreover, Costanzo Festa, was still alive and active at the time. Since he was a singer in the chapel—and probably Master—there would have been many possibilities for the two men to meet and converse. Two years before, when it was first mooted that Michelangelo should paint the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, Costanzo Festa composed a setting for one of Michelangelo’s madrigals (now lost). It was sent from Rome to the artist by Sebastiano del Piombo, in a letter dated 17 July 1533, together with another composition by a Sistine Chapel singer, the equally famous Jean Conseil (Giovanni Consiglion).396 Michelangelo’s response from Florence was quick and enthusiastic, saying that the madrigals had been performed several times already, were considered by experts to be very beautiful and that the artist wanted to express his thanks to the composers.397 The two compositions, sent from that place and at that particular time, seem almost like an invitation or gesture of welcome. It is also assumed that Festa, like Michelangelo, was part of Vittoria Colonna’s circle of Roman intellectuals—an assumption partly based on the existence of his celebrated composition Victoria sola columna.398 – Another striking connection between Michelangelo and the Miserere tradition was a portrait medal by Leone Leoni in 1561, produced in correspondence with the artist. The reverse of the medal has a wandering pilgrim and an inscription from the thirteenth verse of the Miserere psalm: DOCEBO. INIQVOS.V.T.E.IMPII.AD.TE.CONVER (‘Then will I teach transgressors thy ways; and sinners shall be converted unto thee’). Michelangelo was pleased with it and sent his fellow artist a few drawings and a wax model in return.399 The pairing of the artist and the Psalm indicates that the relationship between them had specific meaning for the artistic community at the time.

It seems a possibility, then, that several of the characteristics of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement had to do with its optimization for a certain site and public situation: the darkening of the chapel for the Tenebrae, and the singing of the Miserere. The arrangement of the candles by the altar wall in an inverted V, reported by Wennerberg, corresponded precisely with a console still in place in the upper central part of the fresco, and it explains the importance of the special efforts taken to avoid dust and smoke from settling on the wall. Older paintings had to be sacrificed in order for the effect of the successive darkening of the chapel to proceed undisturbed. In its heavy use of ultramarine, the new wall painting mimicked the starry heaven that was destroyed when Michelangelo painted the ceiling thirty years earlier. The close connection between the wall painting and the ceiling’s representation of God separating light from darkness (luce et tenebrae) was illustrated by Marcello Venusti’s early copy of The Last Judgement in Naples, where the ceiling motif was incorporated into the Last Judgement scene (Fig. 15.3).

Iconographically, the importance attached to the Passion and to symbolic light can be explained, not by any specific theological programme, but by the ritual context in which the painting was to function. As the fresco was primarily meant to be shown during Easter, symbols of the Passion were a natural choice; because of the Tenebrae ceremony, Christ as a symbol of light became a central motif of the fresco, but otherwise the mood is dark and pessimistic. The many figures pleading for mercy are altogether in line with the literary content of the Miserere psalm. In its ritual context, it is an exemplary work of via negativa, emphasizing the importance of going into darkness in order to become fully aware of the divine light. A reason for the Dantesque theme may have been the assumption that the events of his Inferno took place during Easter, from Good Friday until Holy Saturday—an idea presented in a contemporary literary dialogue by Donato Giannotti in which Michelangelo himself participates.400

As for the composition, the generous use of shiny blue ultramarine and the deep blue background of the fresco means the many figures appear to float in the darkening chapel, an effect reinforced by their seemingly random distribution on the wall. The arrangement with the lights being extinguished one by one from the ceiling downwards ensures that the symbolic level, with its references to the sufferings of Christ, is the first to go out of sight. After a while, not even the returning Christ can be seen. The lower level of The Last Judgement represents the part of Hell that threatens cold-hearted and sinful men, but it would not have been fitting to make the question of Heaven or Hell one of the congregation’s placement in the chapel—a ‘blessed’ and a ‘damned’ side in the painting would have had implications for the spectators too, especially at the Tenebrae event. The small grotto above the altar would have been the last thing the viewers saw, a strikingly fitting image and metaphor for the seriousness of mankind’s fate following the death of Christ. All that remained was to confess their sins and beg for mercy: Miserere mei, Deus. Rather than any specific theological or philosophical doctrines, the grotto was placed over the altar because of the effect during the ceremony.

Like Costanzo Festa and the falsobordone-style Miserere, Michelangelo aimed at an aestheticization of the traditional ritual, giving it a shape that would strengthen its emotional effect on all present. He set out not simply to represent certain dogmas, ideas, and texts, but to give substance to the service—taking full advantage of the site and his knowledge not only of the visual arts but of musical, textual, and dramatic qualities as well. During what was a transitory event, the immediate, overwhelming impression of The Last Judgement’s totality was gradually transposed into a fragmented and highly emotional viewing of the work. In adapting his work so closely to the site-specific conditions of the chapel, Michelangelo altered those same conditions beyond recognition, and at the same time helped realize one of the most spectacular multimedia events of all times. The Last Judgement was designed to contain and conduct its own decomposition.